TEXTIL ES AND THE INDU STRIAL REVOLUTION

In 1760, Britain’s textile industry consisted of men and women who sat in their cottages working their own spinning wheels to make thread, which was passed on to weavers. The market for fine muslins was provided by importing quality cloth from India. The smallness of the British enterprise can be measured by how little raw cotton was imported – only around 3 million pounds, which came mostly from South America and the West Indies. By 1789, the situation was transformed. Imports of raw cotton exceeded 32 million pounds, a figure that by 1802 had passed 60 million. The cottage-dweller working away between periodic tendings of the pot over the fire had been replaced by hundreds of employees in huge mills, churning out finished textiles for both the home and export markets at a fraction of the previous price.

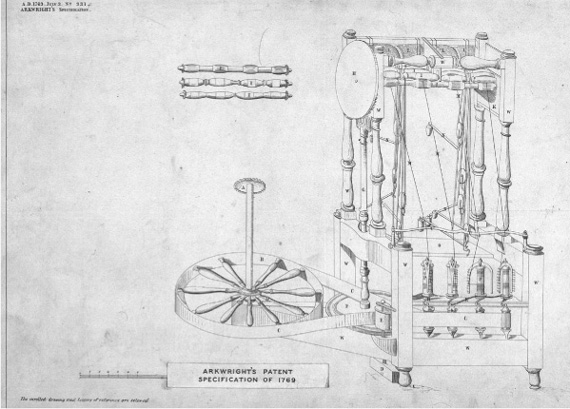

Inventions drove this Industrial Revolution, among which Richard Arkwright’s water frame heralded the most fundamental change in the scale and organization of manufacturing in Britain.

In 1764, James Hargreaves (c.1720–78), an illiterate carpenter and weaver from Lancashire, was credited with devising the ‘spinning jenny’. It represented a significant advance on the traditional tools of the trade because it featured a mobile carriage that allowed multiple spindles to be worked, thereby greatly increasing output. However, it produced brittle thread.

The spinning machine that Richard Arkwright patented in 1769 was different in several respects. It consisted of three sets of rollers that ran parallel to each other and turned the yarn at different speeds, with the fibres twisted and tightened together by a set of spindles. The result was a much stronger thread, which successfully made good-quality cloth from pure cotton.

Other factors were more broadly significant. Hargreaves’ jenny was hand-powered, which made it compatible with the cottage as the place of work. Arkwright’s machine, in contrast, was powered by water and was intended not for the humble home but for large mills yoking the power of rivers. It therefore involved a shift in industrial organization, creating mass-production techniques in factories worked by unskilled labour.

DRIVING FORCES OF THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

1700 Total national coal output is estimated at 2,612,000 tons.

1709 Abraham Darby uses coke, rather than wood or charcoal, to smelt iron ore.

1712 Thomas Newcomen’s steam engine is used to pump out water from mines.

1733 John Kay patents his flying shuttle.

1742 The publisher, Edward Cave, buys Marvel’s Mill in Northamptonshire and converts it into Britain’s first water-powered cotton mill. It soon has over a hundred employees.

1761 The Bridgewater Canal opens, the first canal in Britain to be constructed that did not follow an existing watercourse. Originally connecting Worsley to Manchester, it was extended to the Mersey, at Runcorn, in 1766.

1764 James Hargreaves creates the spinning jenny.

1769 Richard Arkwright patents his water frame.

1772 Manchester and Salford have a combined population of about 25,000.

1773 The first factory-produced all-cotton textiles are made.

1775/6 James Watt’s steam engine greatly improves upon Newcomen’s pump.

1777 The Grand Trunk Canal links the Midlands with the major ports.

1779 Samuel Crompton invents the spinning mule.

1784 Henry Cort patents the puddling process for refining iron ore which, with his steel rolling mill, proves a superior way of producing bar iron from pig iron.

1785 Edmund Cartwright patents his power loom.

1789 The Thames–Severn Canal opens.

1790 The Forth and Clyde Canal opens, allowing vessels to pass through Scotland from the west coast to the east coast.

c.1792 William Murdoch invents gas lighting (but fails to patent it). In 1805 the Philips and Lee cotton mill in Manchester becomes the first to be entirely lit by gaslight.

1800 Manchester and Salford have a combined population of about 95,000.

1815 Sir Humphry Davy invents his safety lamp, permitting deep seams to be mined without igniting flammable gases.

1816 Total national coal output estimated at 15,635,000 tonnes.

The mill that Arkwright opened at Cromford on the River Derwent in Derbyshire in 1771 emphasised the shift in scale. Within a decade it had 5,000 employees. It exemplified the industrial future and, as such, was a disaster for traditional weavers. Work that had previously been undertaken by skilled labourers could now be done, far more quickly and cheaply, by children as young as six. Unable to compete with this new invention, the response of many whose livelihoods it removed was to try to smash it up. A mob broke into Hargreaves’ house and destroyed his working models; in 1779, rioters sacked Arkwright’s mill in Chorley in Lancashire. At Cromford, which already resembled a forbidding fortress, he kept a cannon loaded and ready to fire grapeshot against a similar assault. Innovation in working practices came at the price of an abrasive attitude to labour relations.

The long hours, the tough conditions, the dehumanizing nature of the unskilled work and the reality that so many of the employees were children symbolized all that was least attractive about this fresh way of making profits for factory owners. The poet William Blake encapsulated this in his indelible phrase when he wrote of ‘dark Satanic Mills’. The description was fair but, on the other hand, factories also brought gains. The wages paid were low, yet sufficiently higher than those often paid to farm labourers, prompting them to leave the fields and make instead for the new northern towns and cities growing up around these novel sources of employment. There were knock-on benefits: the factories produced garments at a fraction of their previous price to the purchaser. The cost of living came down and the mass consumer society was born.

One of the copies made of Arkwright’s water frame patent.

The process also, of course, made the likes of Arkwright extremely rich. His story illustrates the social mobility that the Industrial Revolution brought in its wake. He had been born in Preston in 1732, the youngest of thirteen children. His parents could not afford to send him to school and the only education he received was from a cousin who taught him to read and write. He became a wigmaker before turning his mind from hair to thread, although the water frame with which he made his fortune was not, for the most part, his invention. It has always been disputed exactly how much input he contributed to the design – so much so that he lost the patent for it in 1785. It was probably largely the work of John Kay, a former clockmaker from Warrington whom Arkwright engaged. Kay, in turn, developed a design originally made by Thomas Highs, who has also been credited with the prototype for Hargreaves’ jenny.

Whoever came up with the model, it was Arkwright who saw the possibilities for maximizing its potential. He and others like him represented something sufficiently new in England that a French word had to be conscripted: Arkwright was an entrepreneur. He died in 1792 in conditions far removed from the circumstances of his birth – having been awarded a knighthood by King George III and having amassed a fortune estimated at £500,000. The machine that had made his success possible was superseded first by Samuel Crompton’s ‘spinning mule’ and thereafter by other developments as water gave way to steam power, an advance that Arkwright had embraced at his factory in Nottingham. He had, nonetheless, lived long enough to see the economy and society of Britain embark on an extraordinary transformation that set the country on course to becoming the workshop of the world.