In the period immediately after its publication, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman made its author, Mary Wollstonecraft, Europe’s most famous female political writer. Although that reputation ebbed in the succeeding decades, her status was restored during the twentieth century with the embrace of much of her feminist philosophy.

Born in 1759, Wollstonecraft was unhappy in her youth. The family wealth was squandered by a bullying and incompetent father, while her mother openly favoured her eldest son. ‘What was called spirit and wit in him,’ his sister later summarized, ‘was cruelly repressed as forwardness in me.’ She received only brief schooling, a shortcoming for which she subsequently compensated by vociferous reading and teaching herself several foreign languages.

A propitious marriage – as a recurring theme in Jane Austen’s novels emphasized – was the primary means by which middle-class women retained or enhanced their social station. With a minimal dowry, Mary Wollstonecraft’s chances were blighted by her father’s financial ineptitude. She embarked instead upon a career as a teacher and governess, whose rewards were meagre. Women’s education, which had been a feature of Tudor gentry society, had still not fully recovered from the disruptions of the seventeenth century. To make matters worse, Wollstonecraft’s efforts were not greatly appreciated by those who employed her.

In two areas, however, women were established in their own right. Since the Restoration, the stage had offered opportunities to women prepared to risk moral compromise. During the eighteenth century, a second, safer market developed in literature written by – and usually for – women. Wollstonecraft determined to become a writer. In 1787, Joseph Johnson, a sympathetic publisher, brought out her book, Thoughts on the Education of Daughters.

The transforming event was the outbreak of the French Revolution. Britons were divided between those like the Whig politician-turned-Tory philosopher Edmund Burke, who preferred the orderly society of the ancien régime to the bloody anarchy unleashed by the mob, and radicals like Thomas Paine, the author of The Rights of Man (1791), who interpreted events in France as the birth of a new liberty.

Wollstonecraft firmly endorsed the latter view and sought to broaden its message to her own sex. In 1792, Johnson published her A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. An instant best-seller, it was soon translated into French and German and was also brought out in an American edition. It argued that a male-ordered society obsessed by rank and position had confined and stunted female development and self-expression. Furthermore, women had connived in their own disadvantage. Upon attaining their goal of marriage they had proceeded to behave as ‘weak beings . . . fit only for a seraglio!’ Society was constructed so that even ‘civilised women of the present century, with a few exceptions are only anxious to inspire love, when they ought to cherish a nobler ambition, and by their abilities and virtues exact respect’.

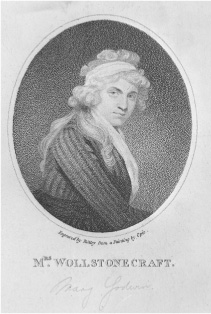

Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–97).

Her own private life exemplified the struggles of women to gain esteem beyond the parameters of conformity. She fell in love with a bisexual married man, but the relationship was broken off when she suggested to his wife cohabiting with them in a ménage à trois. In 1792 she travelled to Paris and there began an affair with an American officer. To protect her from the murderous vengeance of the anti-British French revolutionaries, he registered her at the American Embassy as his wife. However, despite her being pregnant with his child, he largely deserted her to follow his own commercial ventures, and other lovers, before sending her to Scandinavia to conduct his business. Made miserable by his treatment, she twice tried to commit suicide. Rescued once by her maid from an opium overdose and a second time by rowers from drowning under Putney Bridge, she survived, working off some of her pain by using the experience as the basis for an epistolary novel, A Short Residence in Sweden, Norway and Denmark (1796). In the radical philosopher William Godwin she finally met a like-minded man who treated her with respect. Overcoming their mutual opposition to the idea of marriage, they exchanged vows when she discovered she was pregnant by him; but lasting happiness eluded her. In September 1797, aged thirty-eight, she died following complications in giving birth. The child survived and grew up to become the novelist Mary Shelley.

From A Vindication of the Rights of Women, Chapter 2

Women ought to endeavour to purify their heart; but can they do so when their uncultivated understandings make them entirely dependent on their senses for employment and amusement, when no noble pursuits set them above the little vanities of the day, or enables them to curb the wild emotions that agitate a reed, over which every passing breeze has power? To gain the affections of a virtuous man, is affectation necessary? Nature has given woman a weaker frame than man; but, to ensure her husband’s affections, must a wife, who, by the exercise of her mind and body whilst she was discharging the duties of a daughter, wife, and mother, has allowed her constitution to retain its natural strength, and her nerves a healthy tone, – is she, I say, to condescend to use art, and feign a sickly delicacy, in order to secure her husband’s affection? Weakness may excite tenderness, and gratify the arrogant pride of man; but the lordly caresses of a protector will not gratify a noble mind that pants for and deserves to be respected. Fondness is a poor substitute for friendship!

In a seraglio, I grant, that all these arts are necessary; the epicure must have his palate tickled, or he will sink into apathy; but have women so little ambition as to be satisfied with such a condition? Can they supinely dream life away in the lap of pleasure, or the languor of weariness, rather than assert their claim to pursue reasonable pleasures, and render themselves conspicuous by practising the virtues which dignify mankind? Surely she has not an immortal soul who can loiter life away merely employed to adorn her person, that she may amuse the languid hours, and soften the cares of a fellow-creature who is willing to be enlivened by her smiles and tricks, when the serious business of life is over.

Besides, the woman who strengthens her body and exercises her mind will, by managing her family and practising various virtues, become the friend, and not the humble dependent of her husband; and if she, by possessing such substantial qualities, merit his regard, she will not find it necessary to conceal her affection, nor to pretend to an unnatural coldness of constitution to excite her husband’s passions. In fact, if we revert to history, we shall find that the women who have distinguished themselves have neither been the most beautiful nor the most gentle of their sex.

Godwin was heartbroken, but when he published his memoirs he unintentionally severely damaged her posthumous reputation by detailing her bohemian life. As a consequence, she quickly plummeted from her position as the most read and discussed exponent of women’s rights, while the personal details Godwin had revealed provided ammunition for her political opponents. It did not help that her deeply sexual and largely unhappy odyssey did not sit easily with the high moral tone adopted by the female Victorian campaigners. Nevertheless, while her writing produced little discernible gain in the short term, she benefited from a reassessment by the women’s suffrage movement at the end of the nineteenth century. From then on, her standing continued to recover. The liberal attitudes expressed in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman have made the book a central text not only of twentieth-century feminism but of equality itself.