THE CREATION OF THE UNITED KINGDOM’S PARLIAMENT

Back in 1171, Henry II had launched a full-scale invasion of Ireland. In doing so, he cited papal sanction (Rome was concerned about Ireland’s Celtic ecclesiastical traditions); but he was chiefly motivated by greed and the fear that other rivals might establish too strong a foothold there if he did not assert his own authority. Disunited by its competing regional chieftains, the country was taken over piecemeal, with Anglo-Norman barons seizing land predominantly in the south-east. Parliaments were called from 1264. Yet, despite successive campaigns in the fourteenth century, English forces failed to subdue the rest of the island. Indeed, by the fifteenth century, English influence had contracted to the area of the Pale around Dublin. The realization that the whole island could not readily be brought under centralized control ensured its division between the native Gaelic chiefs, the semi-autonomous Anglo-Irish lords and the centre of anglicized leadership in Dublin.

It was Henry VIII who adopted new strategies, seeking to strengthen his own authority while pursuing measures that avoided costly formal colonization. The Dublin Parliament had recognized successive English monarchs as ‘Lord of Ireland’, but in 1541 this title was upgraded to ‘King of Ireland’. In return for acknowledging their royal overlord and English law, the Gaelic chiefs were guaranteed retention of their possessions. Peerages were also conferred upon them in the belief that this would foster their integration and collaboration. However, the adoption of Protestantism and the ‘plantation’ of (largely Scots Presbyterian) settlers in Ulster succeeded only in widening the divide between the colonists and the colonized. Successive uprisings in the last years of Elizabeth I’s reign were put down only at considerable cost.

In the seventeenth century the plight of the Catholic Irish majority worsened significantly. On the eve of the English Civil War, 60 per cent of Ireland was still in Catholic ownership. Atrocities by both sides in the 1640s were followed in 1649 by Oliver Cromwell’s invasion and the ruthless imposition of a new settlement.

Cromwell’s experiment in uniting the Irish and English Parliaments, with (Protestant) Irish MPs sitting at Westminster, was undone upon the Restoration. The Anglican Church of Ireland was given statutory authority as the Established Church. Largely left in place was the Protestant land grab, which engulfed 80 per cent of the country. Except in parts of Ulster where Scottish migration created a Presbyterian culture that was both anti-Catholic and anti-Establishment, the imposition of Anglican landowners without a corresponding Anglican yeomanry defined the class division along a clearly delineated religious faultline. Controlled by the all-powerful Anglican landed gentry, the revived Parliament in Dublin proceeded to pass penal laws that stripped Catholics of most of their remaining rights.

Yet Dublin’s Protestant ‘Ascendancy’ politicians also resented interference from the mainland. In 1720, Westminster restated its legal right to legislate on Ireland’s behalf, a reality made especially evident when rival economic interests clashed. In Dublin, this battle for ultimate authority found in Henry Grattan a leader gifted with the unusual combination of eloquence and moderation. He appeared victorious when, in 1782–3, Westminster – not wanting a repetition of the American War of Independence closer to home – formally renounced its own legislative powers over Ireland. What Britain retained was executive authority through its appointment of a lord lieutenant based at Dublin Castle.

1169 A Norman army occupies Wexford at the request of Dermot MacMurrough, the ousted king of Leinster.

1171 Henry II of England invades Ireland.

1366 The Statutes of Kilkenny attempt to stop the descendants of English settlers adopting Gaelic Irish customs.

1494 The so-called Poyning’s Law asserts that the Irish Parliament is subservient to Westminster.

1541 The Irish Parliament recognizes Henry VIII as king of Ireland.

1560 The Irish Parliament acknowledges the Elizabethan supremacy and Anglicanism as the Established Church.

1592–1603 Rebellion in Ireland is finally suppressed with the surrender of Hugh O’Neill and the assertion of English rule throughout the island.

1608 The plantation of Ulster brings large-scale settlement in the North by Scottish Presbyterians.

1641 A bloody insurrection by Catholics breaks out, in an attempt to regain confiscated lands.

1649 Oliver Cromwell’s forces massacre garrisons at Wexford and Drogheda.

1654 The ‘Cromwellian Plantation’ effectively further curtails Catholic land ownership.

1689 Protestants in Londonderry withstand a 105-day siege by Jacobites loyal to the ousted James II.

1690 At the Battle of the Boyne Protestant forces of William of Orange defeat Catholics loyal to James II.

1695 Penal Laws persecuting Catholics are introduced (by 1714 Catholics own a mere 7 per cent of the land).

1782 The Irish Parliament wins legislative independence from Westminster.

1793 The Catholic Relief Act grants Catholics right to vote on same terms as Protestants.

1798 The United Irishmen’s rebellion is crushed.

1800 The Irish Parliament votes itself out of existence by passing the Act of Union, effective from 1801.

Article First. That it be the first Article of the Union of the Kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland, that the said Kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland shall, upon the 1st day of January which shall be in the year of our Lord 1801, and for ever after, be united into one Kingdom, by the name The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland; and that the royal style and titles appertaining to the Imperial Crown of the said United Kingdom and its dependencies; and also the ensigns, armorial flags and banners thereof shall be such as H.M., by his royal Proclamation under the Great Seal of the United Kingdom, shall be pleased to appoint.

Article Second. That it be the second Article of Union, that the succession to the Imperial Crown of the said United Kingdom, and of the dominions thereunto belonging, shall continue limited and settled . . . according to the existing laws, and to the terms of union between England and Scotland.

Article Third. That it be the third Article of Union that the said United Kingdom be represented in one and the same Parliament, to be styled The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

Article Fourth. That it be the fourth Article of Union that four Lords Spiritual of Ireland by rotation of sessions, and 28 Lords Temporal of Ireland elected for life by the peers of Ireland, shall be the number to sit and vote on the part of Ireland in the House of Lords of the Parliament of the United Kingdom; and 100 commoners (two for each County of Ireland, two for the City of Dublin, two for the City of Cork, one for the University of Trinity College, and one for each of the 31 most considerable Cities, Town and Boroughs) be the number to sit and vote on the part of Ireland in the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom.

It was the French Revolution that provoked London into rethinking legislative devolution. The fear was that Ireland might prove susceptible to the republican spirit emanating from Paris or, worse still, become the launching ground for a French invasion of the British mainland. There were also worries that the Dublin Parliament would seek to pass economic policies injurious to Britain. Such fears were well founded. Although a minor French invasion attempt in 1796 ended ignominiously, two years later the ‘United Irishmen’ launched a major republican uprising. It was defeated. Yet, the scale of the loss of life – perhaps as many as 20,000 lives – underlined the magnitude of the discontent.

How Ireland’s greater political liberty and religious toleration might be achieved without threatening the security of the rest of the British Isles now exercised the government of William Pitt the Younger. London nudged the Dublin Parliament into passing the 1793 Catholic Relief Act, permitting Irish Catholics to bear arms, to serve commissions in the army and (for those with 40-shilling freeholds) to vote. There had, in the previous decade, already been some easing in the restrictions on Catholics in terms of property, law, religion and education. The remaining injustices meted out to the Catholic majority – including their inability to sit in Parliament – still needed to be addressed. The problem was that doing so threatened to destroy the Protestant Ascendancy’s hold on Irish politics and could expect rough treatment in the Dublin Parliament. William Pitt’s solution was to incorporate Irish representation into a United Kingdom-wide Parliament. Thus Catholic emancipation could be granted without those enfranchised becoming more than a small minority at Westminster.

The first attempt was defeated in 1799. But the scheme’s advocates persevered. Where argument and persuasion failed, bribery – the tactic that overcame opposition to union in the Scottish Parliament – was successfully deployed in the Irish Parliament. Money and promises of titles proved sufficient inducement to convince waverers and hard bargainers. The Irish Parliament voted itself out of existence by 158 votes to 115.

The Act of Irish Union was passed in August 1800 and came into force on New Year’s Day 1801. Dublin’s 300-member House of Commons was abolished and in its place, 100 Irish seats were created in the new United Kingdom House of Commons. The Irish peerage also got to vote on which twenty-eight of them would take their seats in the enlarged House of Lords at Westminster. This arrangement resembled that introduced by the 1707 Act of Union for the Scottish peers, except that the Irish representative peers would sit for life. And, unlike the leaders of the Church of Scotland, four Church of Ireland bishops, serving in rotation, were also admitted to the House of Lords.

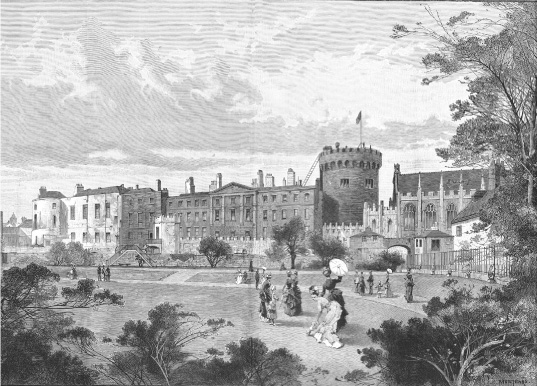

Dublin Castle, from where the lord-lieutenant as viceroy and the chief secretary administered Ireland for the British Crown.

Catholic acquiescence in the Anglo-Irish Union had been bought on the pledge of full religious emancipation. Pitt resigned when the intransigence of George III prevented him delivering on his promise. Britain’s side of this bargain was thus granted only in 1829 when the Catholic Emancipation Act finally became law. The scarcely tenable situation in which the Established Church in Ireland was Anglican – despite the Presbyterianism of Ulster and overwhelming Catholicism of the rest of the country – endured until its disestablishment finally came in 1869. Although as early as 1832 there were thrity-nine Irish MPs at Westminster opposed to the Act of Union, the long and tortuous path to repeal the legislation of 1800 would take 120 years.