In the popular consciousness, the link between Roman Catholicism and continental despotism was the single greatest barrier to the acceptance of Rome’s adherents in British society. At its most virulent, this animosity lasted for as long as there remained a plausible likelihood of a successful, French-aided, Jacobite invasion bent on undoing the work of the Glorious Revolution. The threat was finally removed by the crushing defeat of Prince Charles Edward’s Jacobite forces at Culloden in 1746. In any case, the number of Catholics had by then shrivelled to a tiny proportion, mostly confined to pockets in the countryside where a few aristocrats (presumed eccentric) retained the faith of their forebears. Despite its being the dominant faith in Ireland, perhaps no more than 2 per cent of the population of England and Wales were Catholic.

However, the sense of security of the Hanoverian settlement after 1746 meant that Catholics found themselves increasingly unmolested when opening schools and chapels, even though such activities were still illegal. Their numbers, particularly among the artisan class, began to swell in towns and cities, but they remained a distinct minority, at the mercy of events and sporadic demagoguery. In 1778, following the passage of the Catholic Relief Act, ‘No Popery’ riots in Edinburgh and Glasgow greeted the readmittance of Catholics to the armed forces and the removal of restrictions on their purchasing property, scaring the government into scrapping plans to make the law applicable in Scotland. London was convulsed in ten days of fighting when, two years later, Parliament refused to bow to the demands of the Protestant Association, led by Lord George Gordon, to repeal the 1778 legislation for the rest of Britain. The houses of Catholics were burned down and Newgate prison and other buildings were ransacked. George III felt compelled to call up 12,000 troops to fire on the mob and restore order. In all, the anarchy of the Gordon riots caused around 500 casualties. Although acquitted on treason charges, Lord George Gordon was ruined. He later converted to Judaism, was imprisoned for libelling Marie Antoinette and died in Newgate.

1661 The Corporation Act restricts the holding of government and town office in England and Wales to those taking the Anglican Communion.

1678 The Test Act forces all MPs and peers to deny transubstantiation.

1689 The Toleration Act grants religious liberty to Protestant Dissenters.

1698 The Popery Act gives financial rewards to those who expose clandestine Catholic worship and makes Catholic teachers liable to serve a life prison sentence.

1714 The Schism Act requires all school headmasters in England to be licensed by an Anglican bishop. The Occasional Conformity Act removes a loophole through which Catholics and Dissenters can evade the Test and Corporation Acts. Both acts are repealed in 1718.

1723 State grants are introduced to support Dissenting ministers.

1766 The papacy finally recognizes the house of Hanover as the legitimate monarchy in Britain.

1778 The Catholic Relief Act removes semi-redundant statutes that placed Catholic priests at risk of arrest for felony and restricted Catholics’ rights in passing on and acquiring property. Catholics are permitted to join the armed forces.

1780 The Gordon riots in London witness mob violence against extending Catholic rights.

1791 The Catholic Relief Act guarantees Catholic freedom of worship and education, as well as admission to the legal profession. Catholic property owners gain the right to vote.

1813 Unitarians are included in the terms of the Toleration Act.

1821 The Catholic Relief Bill is passed in the Commons but later defeated in the Lords.

1828 The repeal of the Test and Corporation acts opens public office to Dissenters.

1829 The Catholic Emancipation Act removes the remaining legal barriers confronting Catholics, including the right to sit in Parliament.

Moderate opinion was horrified not just by the anti-Catholic rabble on the streets of London but also by the anti-clericalism of the Terror in France. The sanctuary given to French Catholic royalty, aristocrats and priests fleeing the atheist ideologues of the French Revolution did much to temper previous attitudes. Unusually, Britain found itself in alliance with Bourbon absolutists, by which time native Catholics had made a statement on where their primary loyalties lay. In 1788, the four Catholic ‘Vicars Apostolic’, together with 240 priests and 1,500 laymen, issued a protestation renouncing the Vatican’s temporal authority. The government responded to this overture in 1791 with legislation removing Catholic religious disabilities and making them free to worship without the threat of having their chapels or schools closed down. Catholics owning property with an annual rental of £2 or more were granted the right to vote. However, one major cause of emancipation remained beyond their grasp: the right to sit in Parliament and hold civic or state office.

Seeking to address the discontent of Ireland’s Catholic majority, William Pitt the Younger had in 1800 attempted to link the union of the British and Irish Parliaments with full Catholic emancipation. George III, however, remained obstinate, fearful of triggering another Gordon riot and insisting that approving such rights breached his coronation oaths. Without sufficient Cabinet support to face down his monarch, Pitt felt compelled to resign on the matter. Yet the Irish problem would not go away. In 1823, Daniel O’Connell founded the Catholic Association, a pressure group demanding full emancipation. At the County Clare by-election in 1828 he was returned as the MP but was unable to take his seat at Westminster on account of his religious faith.

From the Catholic Emancipation Act, 1829

Whereas by various Acts of Parliament certain restraints and disabilities are imposed on the Roman Catholic subjects of H.M., to which other subjects of H.M. are not liable; and whereas by various Acts certain oaths and declarations, commonly called the declaration against transubstantiation, and the declaration against transubstantiation and the invocation of Saints and the sacrifice of the Mass, as practised in the Church of Rome, are or may be required to be taken, made, and subscribed by the subjects of H.M., as qualifications for sitting and voting in parliament, and for the enjoyment of certain offices, franchise, and civil rights: be it enacted . . . that . . . all such parts of the said Acts as require the said declarations, as a qualification for sitting and voting in Parliament, or for the exercise or enjoyment of any office, franchise or civil right are (save as hereinafter provided and excepted) hereby repealed.

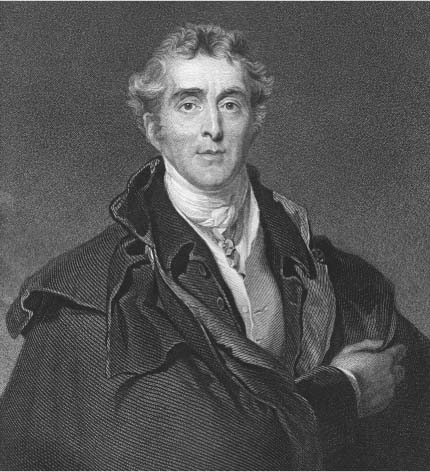

As the Irish-born scion of a Protestant Ascendancy landowning family, the prime minister, the duke of Wellington, was not naturally sympathetic to O’Connell’s cause. Nevertheless, when faced with the possibility of serious disorder in Ireland, he felt compelled to act against his instincts. In pushing through Catholic emancipation he staved off the possibility of civil war in his native land, but at a cost. The issue divided his Tory Party, ensuring that it would be out of office for most of the following decade of reform.

When the act passed into law on 13 April 1829, Catholics were finally allowed to sit in Parliament as well as on lay corporations. Only a small number of restrictions were placed on their admittance to the highest offices of state: they could not become lord chancellor, keeper of the great seal, lord-lieutenant of Ireland or high commissioner of the Church of Scotland. The case for allowing the head of state to become Catholic was not seriously considered. It was unthinkable that the monarch, as supreme governor of the Church of England, would be (or would marry) a Catholic; allowing even the possibility would have involved tearing up the whole Glorious Revolution settlement. A nod to Protestant sensibilities also prevented Catholic clergy standing as MPs or wearing their vestments outside church.

Field Marshal Arthur Wellesley, 1st duke of Wellington (1769–1852), Anglo-Irish soldier and statesman. As prime minister from 1828 to 1830, the hero of Waterloo was compelled to act against his instincts in pushing through Catholic emancipation. In doing so, however, he staved off the possibility of civil war in Ireland.

The Catholic Emancipation Act had considerable constitutional implications. The rights of the Established Church could be determined by legislation passed by politicians who were not its communicants. The admission to Parliament of Jews in 1858 and atheists in 1886 meant that MPs did not even have to be Christian. The inclusion of the atheists particularly outraged the leaders of Britain’s Catholic community. By then, massive Irish emigration had transformed the visibility of the Catholic faith across the mainland’s great cities on a scale that few involved in the 1829 legislation could have foreseen.