The 1832 Reform Act scarcely touched the labouring classes. Indeed, the insistence of Whig politicians that their legislation concluded – rather than commenced – the process of widening political representation suggested that the working classes faced permanent exclusion from the political process.

Not satisfied that their interests were taken into account by those in authority, a Co-operative storekeeper, William Lovett (1800–77), and his associates founded the London Working Man’s Association in 1836. Run by the working class for the working class, it was a pressure group that aimed to secure for labourers the same rights as the middle and upper classes enjoyed.

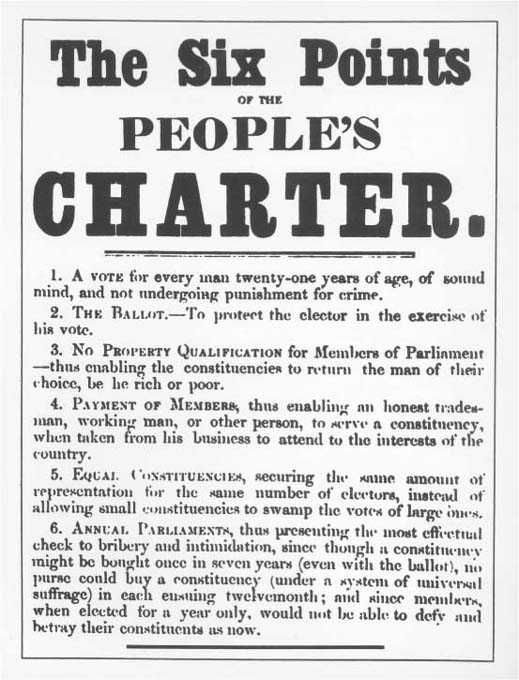

The association’s political objectives were drawn up by Lovett, assisted by the Radical MP Francis Place, in a document entitled the ‘People’s Charter’. Published in May 1838, it consisted of six demands: universal suffrage for all males (Lovett was dissuaded from including women); annually elected parliaments; voting by secret ballot; abolition of the property qualification for MPs; the payment of MPs; and equally sized constituencies. The common thread uniting these demands was the social broadening and greater accountability of parliamentary government. It could be decided later what policies the resulting democracy might adopt.

The People’s Charter became the common ground bringing together otherwise geographically and ideologically disparate radical and working men’s organizations. Support was strong and especially vocal in the mill towns of Lancashire, although the waxing and waning of the Chartist campaigns closely followed the trade cycle’s consequences for these communities. Many of the leading activists were skilled artisans, literate figures who were well versed in radical publications. Their views on other issues ranged from protectionism to advocacy of free trade and from pro-industrialization to a Luddite desire to return to cottage industries supplying an agrarian-based economy.

The six demands of the People’s Charter, published in 1838.

It was Chartism’s mixed blessing to attract the energy and attention-grabbing skills of Feargus O’Connor (1794–1855). An Irish MP who had lost his County Cork constituency in 1835, O’Connor began campaigning across the British mainland on the Chartist programme with a mixture of oratorical zeal and scarcely concealed menace, assisted by the newspaper he controlled, the Northern Star. For all his passion, his personality was a divisive factor in the movement and helped its opponents characterize it as the dangerous instrument of an aspiring demagogue.

The ‘People’s Charter’ became tied to a parallel innovation in working-class agitation. This was the Convention of the Industrious Classes, a shadow parliament that aimed to set the political agenda. Its delegates met in London in February 1839 and began debating what to do if the real Parliament did not bow to the Charter’s demands. Despite the many divisions of opinion, agreement was reached that in this eventuality a general strike would be called to bring the politicians to their senses.

Westminster was not so easily intimidated. When, in July 1839, a copy of the Charter was presented to Parliament with the endorsement of 1,200,000 signatures, the Commons divided, 235 votes to 46, against bothering to discuss its demands. Having moved to Birmingham the Convention was becoming increasingly fractious and broke up in September. With little sign of a nationwide appetite for a general strike, plans for direct action were scaled back. Some hotheads called for a rising, which resulted in November in an ill-conceived skirmish between Chartists and soldiers at Newport, in Wales. The instigators were sentenced to transportation (but pardoned in 1854) while more moderate activists received short jail sentences.

It was during this period that Lovett and O’Connor’s paths diverged. Lovett concluded that a movement confined to working-class membership was doomed and that the only hope lay in alliance with the middle classes. The problem with this was that much of the middle class viewed uneducated labourers as the very people with whom they did not wish to share the franchise. Keen to remain the leader of his own movement, O’Connor, by contrast, hoped to lead the National Charter Association, founded in July 1840, on the twin delusions that centralization could be achieved and victory delivered.

A second petition to Parliament in 1842 attracted 3,317,752 signatures. Parliament did not hide its lack of interest, again rejecting considering the Charter by 287 votes to 49. In 1848, while Europe was convulsed by revolutions, a third and final petition was organized. What was intended as a mass rally on Kennington Common proved smaller than anticipated and dispersed in the rain, having been prevented from marching towards Parliament by the police (back-up troops were on standby). Bathetically, the petition was delivered in three cabs instead. The large number of genuine signatures were discredited by the smaller number of autographs purporting to be those of the duke of Wellington or Mr Punch.

The damp squib of 1848 was a sign of Chartism’s terminal decline and it ceased to be a significant force after 1854. O’Connor’s reputation was ruined by the collapse of a subscriber-driven scheme that he had devised for small landholders, and in 1852 he became insane, dying three years later. Improving economic conditions did much to quell political unrest. Ex-Chartists increasingly turned to other causes, particularly those that motivated Protestant Nonconformists: educational reform and temperance campaigns against the ‘demon drink’.

However, the Great Charter was not a failure, merely a false dawn. A successful working-class political movement did eventually emerge in the guise of the Labour Party, and, ultimately, five of the Charter’s six demands were adopted. The MPs’ property qualification was scrapped in 1858; the secret ballot was introduced in 1872; legislation in 1876, 1884 and 1918 helped create nearly equal-sized constituencies; in 1911 the payment of MPs came in; universal male suffrage was achieved in 1918. Only the least sensible of the Chartists’ demands – annual general elections – has never reached the statute books.