POPULAR NOVELS, THE VICTORIAN SOCIAL CONSCIENCE AND THE REVIVAL OF THE CHRISTMAS SPIRIT

Dismissed by some critics as a mere creator of caricatures and mawkish sentimentality, Charles Dickens (1812–70) was, by most popular measures, the greatest novelist in British history and, without question, the most influential.

The fact that the term ‘Dickensian’ is still used, even by those who have not read his books 150 years after they were written, confirms his centrality to the British psyche. In Dickens’s lifetime and thereafter, his audience was never confined to the refined tastes of polite society nor to the ranks of light popular entertainment. Rather, his novels crossed social boundaries, appealing to all classes of reader and both sexes. That was part of their power. Few, if any, politicians, philosophers or artists gained broader acknowledgement or wider appreciation for doing what Dickens did best: holding a mirror up to Victorian Britain and exposing its blemishes.

The social evils were too great and too entrenched to be expunged by any single social reformer, but Dickens influenced movements that attacked some of the most degrading aspects of nineteenth-century life. His novels highlighted the cruelty of the Poor Law of 1834 and, in particular, the workhouse. Many of his works, most memorably Oliver Twist, laid bare the brutal treatment of children. His depiction of the Marshalsea prison in Little Dorrit helped spur the eventual scrapping of imprisonment for debt in 1869. Bleak House painted an uninspiring portrait of the self-serving aspects of the legal system, in particular, Chancery.

A recurring theme in Dickens’s work is the fragility of comfort and the sudden reversal of fortune, where wealth may be either won or lost. Of this he had direct experience. The son of a navy pay-office clerk who fell into debt and was sent to the Marshalsea, at the age of twelve Dickens was wrenched out of a comfortable, middle-class existence and put to work in a warehouse, labelling blacking pots. Eventually, the family fortunes recovered so that he was able to complete his schooling, becoming first a solicitor’s clerk and then launching his career in journalism, as a parliamentary reporter. Nevertheless, his truest vocation was to be a novelist and he made his name in 1836 with The Pickwick Papers.

In this greatly loved work, Dickens constructed a cosy, snow-bound image of Christmas. Prior to the mid-seventeenth century, the twelve days of Christmas had been a time of nationwide conviviality, charity, gluttony, intoxication and neighbourliness. However, although the prohibitions and censure of Puritans did not outlive the English republic of the 1650s, the festival’s spirit of bonhomie had become critically dampened, until by the 1820s it was a shadow of its former self. Disheartened by this, Dickens painted a nostalgic picture of Christmas’s old, generous-hearted traditions that very effectively reminded readers what they were missing.

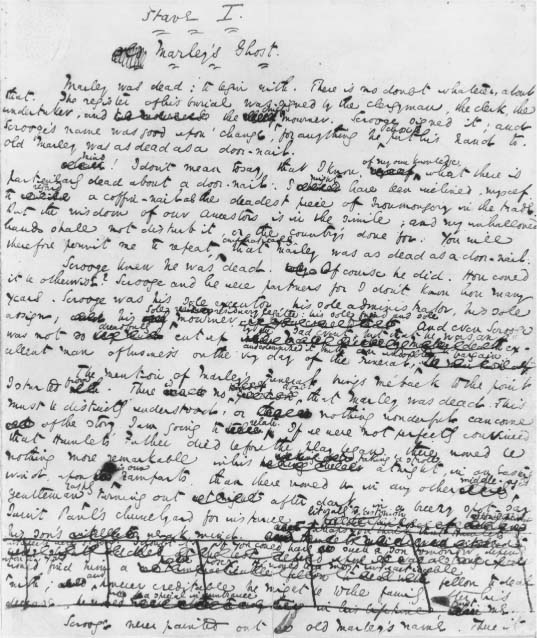

The Pickwick Papers was just the beginning. It was A Christmas Carol that forever imprinted itself upon our notions of the festive season. The idea came to him suddenly in October 1843, when he was still only thirty-one. He worked on the manuscript at high speed over a six-week period, adding and crossing out as he went along. A Christmas Carol was ready for publication on 19 December in a small bound volume, with four illustrations by the Punch cartoonist John Leech. Copies were priced at 5 shillings.

A Christmas Carol tells the story of Ebenezer Scrooge, a cold-hearted miser concerned exclusively with his own business, who regards the good fellowship of Christmas as ‘humbug’. As he retires for the night on Christmas Eve he is visited by a succession of ghosts, starting with that of his late business partner, warning him of the consequences if he does not mend his ways. The Ghost of Christmas Past shows Scrooge how his selfishness drove away a former love and contrasts his indifference to Fred, his nephew, with the sympathy that Fred’s mother once bestowed on Scrooge during his own unhappy childhood. The Ghost of Christmas Present takes Scrooge on a countrywide tour of the Christmas celebrations staged by even the poorest families, including that of his clerk, Bob Cratchit, whose invalid son, Tiny Tim, will die if Scrooge does not become more charitable. The Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come is a dark, hooded figure who does not speak but whose bony hand points to Scrooge’s own depressing demise, robbed on his deathbed and unmourned in his grave. Perturbed and frightened, Scrooge repents and on Christmas morning begins his path to rehabilitation. He joins his nephew Fred’s lunch party, joyfully gives money to charity, sends a large turkey anonymously to the Cratchit family for their Christmas feast and decides he should henceforth be like a second father to poor Tiny Tim. Through living all year long in the Christmas spirit, Scrooge finds redemption.

Charles Dickens’s original manuscript: the opening page of A Christmas Carol, 1843.

Marley’s Ghost. John Leech’s etching for the first edition of A Christmas Carol.

A Christmas Carol was published at a time when few workers had more than one day’s festive holiday and the habit of exchanging presents was not widespread. It reminded readers of the fate of disadvantaged children in the month of the commemoration of Christ’s Nativity. Furthermore, it warned the well-off that giving was an obligation as well as a pleasure. They should not close their eyes to the fate of the poor and pretend that the dehumanizing workhouse was all that they deserved.

No other secular work did more to revive the notion of Christmas as the season of goodwill than Dickens’s simple morality tale. Coincidentally, it was published at almost exactly the same moment that Henry Cole (subsequently the promoter of the Great Exhibition) commissioned for sale the first printed Christmas card – of a family united at the dinner table celebrating a festive meal. Dickens’s offering was an immediate success, although he did not greatly benefit personally. Because of the high production costs that he had chosen to incur, having fallen out with his publisher Chapman and Hall, he made only £130 from the initial sale. When he sued the publishers of an unauthorized edition for piracy, he won the case but had to meet the £700 legal costs himself.

Nonetheless, the speed with which others rushed to make money from the book, not least in the theatrical adaptations that attracted eager audiences, testified to its wide appeal, on the far side of the Atlantic as well as at home. In the United States, Dickens is also celebrated as a founding father of the traditions of the modern Christmas. It was one of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s annual rituals to read Scrooge’s story aloud from beginning to end. In Britain, too, the tale seems destined to remain relevant for many a Christmas yet to come.