JOSEPH PAXTON’S INOVATION IN ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN

On 1 May 1851, Queen Victoria opened the ‘Great Exhibition of Works of Industry of All Nations’ in London’s Hyde Park, describing the occasion as the greatest day in the country’s history. It was the world’s first major international exhibition and, over the next six months, 6 million visitors came to see what the industrial and commercial revolution was bequeathing mankind. The single greatest wonder, however, was the ‘Crystal Palace’ that housed it.

It was the satirical magazine Punch that christened the temporary exhibition hall with the name by which it would be forever celebrated. Surprisingly, the revolutionary structure was not the work of any of the great Victorian architects but rather of a garden expert.

Joseph Paxton (1803–65) started his professional life tending the flora of a park in Bedfordshire before becoming head gardener at Chatsworth, the magnificent Derbyshire estate of the dukes of Devonshire. There, he demonstrated his self-taught technical expertise by designing a deceptively delicate conservatory that was, at the time, the largest glass building in the world.

The principles upon which the glasshouses of Chatsworth soared informed Paxton’s greatest project. He had observed the strength of a species of giant water lily, the Victoria amazonica, by sitting his daughter Annie upon one and floating her across a pond. It inspired Paxton to demonstrate how modern materials and natural forms could unite to produce vast buildings that were structurally strong, yet simple in form and relatively cheap to construct.

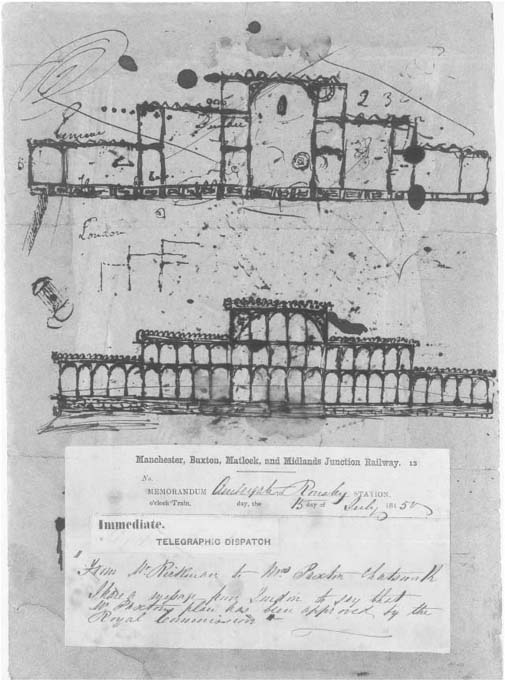

Having been drafted in to produce a design for the Great Exhibition’s main hall at short notice, Paxton did so on blotting paper with a sketch doodled while attending a board meeting. In this approach, as in its method of execution, Paxton’s proposal could not have been more different from the mostly laboured and heavily ornamental schemes offered by the 245 architects who had originally submitted entries. Paxton’s solution could be assembled quickly (in itself a major recommendation, given the fast-approaching deadline) by slotting together prefabricated sections. Indeed, the structure was completed within nine months of the submission of his plans. Wrought-iron ribs were raised into position to provide the frame and backbone, supplemented with wood casements and 293,000 panes of glass. Modern construction methods were used. Sliding along a trolley on rails, each glazier could fit over one hundred panes a day. A public outcry at the prospect of felling Hyde Park’s ninety-foot-high elm trees meant that the building had to be tall enough to accommodate them inside. When it was finished, it was, at over a third of a mile long, the largest enclosed space in the world. With its nave and transept, it resembled a secular cathedral, one that proclaimed the birth of modern architecture.

Joseph Paxton’s inspirational doodle on blotting paper for the ‘Crystal Palace’.

The early impetus for the exhibition had been provided by Henry Cole, an Assistant Keeper of Public Records. In 1845, while campaigning for free trade and cheaper bread, the Anti-Corn Law League had successfully run bazaars showcasing British manufactures and raising money through company stalls. Cole proposed an altogether grander venture, which, being international in scope, would provide a forum for British and foreign leaders of industry and commerce to meet, learn and exchange ideas. His scheme attracted the influential support of Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert, who chaired the Royal Commission established to investigate its practicality.

1837 Queen Victoria succeeds her uncle, William IV. Charles Dickens publishes Oliver Twist.

1840 Victoria marries Prince Albert.

1841 Augustus Pugin’s True Principles sets out the argument for the Gothic Revival in architecture.

1843 The ‘Disruption’ occurs between the Church of Scotland and the Free Church of Scotland.

1845–9 The Irish suffer the potato famine.

1846 The Corn Laws are repealed.

1847 The ‘Ten-Hour’ Factory Act is introduced.

1851 The Great Exhibition is mounted in Hyde Park.

1853–6 The Crimean War is fought by Britain, along with France and the Ottoman Empire, against Russia.

1857 The Indian Mutiny challenges British rule.

1858 The first transatlantic telegraph cable is laid: permanent connection is achieved in 1866.

1859 Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species and J. S. Mill’s On Liberty are published.

1861 Prince Albert dies, sending Victoria into years of mourning and public withdrawal.

1865 Lewis Carroll publishes Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

1868 The last public execution takes place.

1876 Queen Victoria becomes Empress of India. Alexander Graham Bell patents the telephone.

1878 W. S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan’s HMS Pinafore is performed.

1886 The first Irish Home Rule bill is defeated. The Liberal Party splits.

1895 The National Trust is founded.

1899–1902 The second Anglo-Boer War is fought.

Upon opening, the Great Exhibition featured displays from 17,000 exhibitors, which ranged from machinery to fine art. It also attracted visitors from all ranks of society, many of whom availed themselves of another novelty provided for their convenience – public lavatories. Arranging a deal with the Midland Railway, travel promoters like Thomas Cook helped organize the flood of tourists. By the time it closed in October 1851, the Exhibition’s profitability was such that the proceeds were used to buy land in South Kensington upon which, in time, the Science, Natural History and Victoria and Albert museums were built: a considerable cultural, scientific and educational legacy.

Paxton was knighted, became MP for Coventry and designed Mentmore Towers in Buckinghamshire for the Rothschild family in a rich, neo-Jacobean style, which, while aesthetically magnificent, was far removed from the masterwork that made him one of the most influential fathers of modern architecture. Conceived at rapid speed as a temporary structure, the Crystal Palace endured for eighty-five years. It was disassembled and put back together again on Sydenham Hill, where it remained as a venue for exhibitions and concerts until destroyed by fire in 1936.