‘Deeds not words’ was Mrs Emmeline Pankhurst’s exhortation to her Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). Suffragette militancy might therefore be better represented by a brick and shards of broken glass, or a padlock attached to iron railings, than by a document. Whether direct action helped or hindered the cause of women’s enfranchisement is still actively disputed today. Such tactics were denounced at the time by the far more popular National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), which campaigned tirelessly and, ultimately, successfully to win the moral and intellectual high ground of the debate.

When localized female suffrage groups came together to found the NUWSS in 1896, it seemed likely that at least some women were about to be granted the vote in national elections. The following year, a private members’ bill reached as far as the second reading stage at Westminster, where it was approved by 230 votes to 159 before running out of parliamentary time. Rationally, it seemed a logical extension of what had already been enacted for local government, where women ratepayers had won the right to vote in 1869 and had been able to sit on parish and district councils since 1894. With increasing numbers of them paying their own taxes, the old cry of the American colonists was revived: ‘No taxation without representation.’

Yet, despite the mildly supportive views of two successive Conservative prime ministers, Lord Salisbury and Arthur Balfour, not a single bill or even a resolution was brought before Parliament between 1897 and 1904. Hope for change was revived when the Liberal Party’s landslide election victory of 1906 created a House of Commons with, at least notionally, a far stronger majority in favour of women’s suffrage, although the new government failed to actively promote legislation. Neither the prime minister from 1908, Herbert Asquith (still less Mrs Asquith), nor successive home secretaries supported the cause.

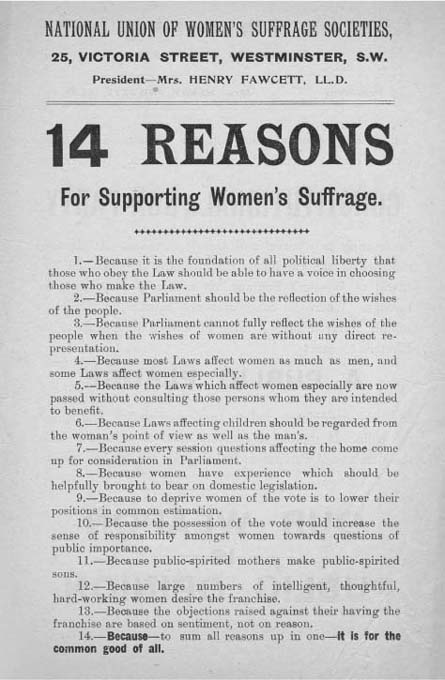

The NUWSS’s fourteen-point statement of 1912, arguing the case for women’s suffrage.

The attitude of the Liberal government was disappointing to the NUWSS, whose president, Millicent Garrett Fawcett (1847–1929) was the widow of a noted Liberal MP. In Manchester, it was as much frustration with the half-hearted attitude of the national Independent Labour Party that stirred the widow of one of its activists, Emmeline Pankhurst (1858–1928), to found the WSPU in 1903.

Initially, Mrs Fawcett’s NUWSS and Mrs Pankhurst’s WSPU ran rival but essentially complementary campaigns. The former were known as Suffragists and the latter as Suffragettes (a term actually coined by the Daily Mail). To begin with, Suffragists neither joined in with nor greatly condemned the more headline-grabbing tactics of Suffragettes, whose efforts to keep the issue at the centre of attention included disrupting public meetings, heckling Liberal politicians and serving prison terms for breaching the peace.

Millicent Fawcett, who did not support fighting for constitutional liberties by unconstitutional means, came to deplore Emmeline Pankhurst’s belief that ‘the argument of the broken pane, is the most valuable argument in modern politics’. The two groups began to diverge sharply when the Suffragettes turned first to vandalism, smashing windows and slashing Velasquez’s Rokeby Venus in the National Gallery, then to arson – including an attack on a station and a school – and ultimately to planting bombs, whose failure to kill anyone was as much chance as design.

Efforts in Parliament to pass suffrage legislation were hampered for several reasons. Some MPs no longer wished to be associated with a cause being advocated through intimidation (and it can probably be safely assumed that not many converts at Westminster were won over by the call for ‘Votes for Women, Chastity for Men’, the new slogan of Mrs Pankhurst’s daughter and fellow activist, Christabel). The parliamentary arithmetic also became less promising after 1910 when the eighty-four Irish Nationalist MPs decided to oppose women’s suffrage on the grounds that it would take up legislative time that was better spent passing Irish home rule. The prevalence of women activists in the campaign against the ‘demon drink’ led some politicians to fear that the practical consequence of giving them the vote would be the introduction of Prohibition, while those of an imperialist frame of mind questioned whether the empire could be defended by female voters. For many MPs, of course, the real root of their objection was naked misogyny.

There was also the question of which women should get the vote. With a third of adult males still unenfranchised, the options were either for all women to gain the suffrage as part of a universal adult franchise bill or for prospective women voters to be subject to the existing property qualifications applicable to men. Whilst the NUWSS were prepared to settle, as an interim measure, for the latter, some Liberals saw it as an unattractive compromise calculating that it would merely add more Tory voters to the electoral register. The best chance of getting legislation onto the statute books came in 1913, when an amendment to include women was attached to legislation extending the male franchise. The opportunity was lost when the Speaker of the House of Commons ruled it out of order on the grounds that it fundamentally altered the nature of the bill.

Where the Suffragette campaign did succeed was in inciting the brutality of the state. Imprisoned Suffragettes went on hunger strike and were force-fed through methods indistinguishable from torture. In 1913, the home secretary introduced a legal novelty with the ‘Cat and Mouse’ Act, which released women prisoners on hunger strike only to reimprison them once they had recovered. In that year the cause also gained its martyr when Emily Wilding Davison either threw herself or fell (she took her intentions to the grave) under the king’s horse at the Derby. It was a time of desperation. The Pankhursts’ Suffragette movement suffered splits and, with the number of new recruits dwindling, stopped publishing details of new members once they fell below 1,000 a year. In contrast, the membership of Millicent Fawcett’s non-violent Suffragist NUWSS soared from 21,000 in 1910 to nearly 100,000 by 1914. In choosing to ally itself with the Labour Party, the NUWSS appeared likely to cause the Liberals significant damage, prompting David Lloyd George to open talks with the NUWSS to secure a measure of women’s suffrage ahead of the next election. Before anything could be finalized, the First World War broke out.

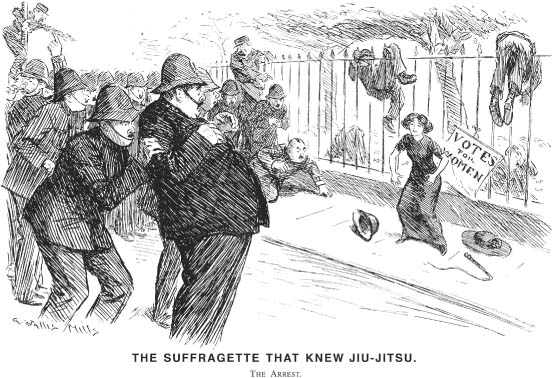

How Punch magazine depicted Suffragette militancy in the early 1900s.

Winding down their campaign, some Suffragists, including Mrs Fawcett, supported the war, many of them getting involved in nursing and relief work, although some ran pacifist campaigns. Both Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst loudly backed the war. The common effort against Germany created a new situation in which former domestic foes could be reconciled. With the argument for granting adult male suffrage being enhanced by the patriotic endeavours of the armed forces in France, so the contribution that women were making to the war effort on the home front was cited as a reason for extending the vote to them too. Certainly, the assertion that the empire was not safe in women’s hands was shot to pieces. When the conflict ended in 1918, the Representation of the People Act gave the vote to all men over twenty-one and all women over thirty.

Both the WSPU and the NUWSS disbanded, although the latter re-formed in a new guise to campaign for the removal of the remaining sexual discrimination in the age at which the vote was granted. Victory was won in 1928 when Stanley Baldwin’s government finally introduced an equal franchise for all men and women over the age of twenty-one. Shortly afterwards, Mrs Pankhurst died, having been selected as the Conservative candidate for Whitechapel. By then, she, no less than British society, had undergone an extraordinary transformation.