THE PHILOSOPHY OF BRITISH SOCIALISM

The Labour Party was founded, as the Labour Representation Committee, in 1900 with the aim of securing parliamentary seats for working-class politicians. Drawn from various pre-existing groups and the trade unions, its members may have adhered to socialist tenets, but the promotion of socialist ideology was not the new organization’s stated objective. Indeed, the failure to be explicitly doctrinal quickly ensured the disaffiliation of the Marxist Social Democratic Foundation.

In its first years, the Labour Party (as it became in 1906) drew strength from two developments. In 1903, it negotiated a secret deal with the Liberal Party to avoid running against each other in constituencies where the chances of splitting the progressive vote risked letting in a Conservative. Assisted in this way, Labour won twenty-nine seats in the 1906 general election and began to assume critical mass. The ‘Lib-Lab’ pact, however, did not survive the First World War. Of greater long-term significance, in terms of members, leverage and funding, was the Labour Party’s role as the political wing of the trade union movement. Between 1910 and 1914, the number of trade unionists in Britain rose from 2.5 million to over 4 million. By 1920 it had doubled to more than 8 million.

The First World War provided Labour with both a test and an opportunity. Unable to support the conflict, the pacifist-minded Ramsay MacDonald (1866–1937) resigned as chairman of the Parliamentary Labour Party. However, his pro-war successor, Arthur Henderson (1863–1935), joined the Cabinet. Labour MPs were thus to be found sitting both on the government and on the opposition benches, yet the division in their ranks proved less strategically calamitous than those that tore the Liberal Party apart. The latter took the form of a highly personal fight between Herbert Asquith and David Lloyd George, with the result that in 1916 the latter replaced Asquith as prime minister in the coalition government. To this clash of personalities was added the further fracturing of common Liberal purpose over differing notions of how the war should be prosecuted.

Clause IV of the Labour Party Constitution, 1918

To secure for the workers by hand or by brain the full fruits of their industry and the most equitable distribution thereof that may be possible upon the basis of the common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange, and the best obtainable system of popular administration and control of each industry or service.

[words in bold added in 1929]

Although the war was still not won when Labour convened its party conference at Nottingham in January 1918, it found itself in a far stronger position than previously. The power of the state was being deployed to secure military victory, blowing away many former notions of laissez-faire non-interference. A collectivist spirit was allied to calls for ever greater redistribution of wealth. If soldiers were to be conscripted to win the war, so the argument ran, there should be a ‘conscription of wealth’ to follow. At the same time, the defection from liberalism of pacifist-minded, middle-class intellectuals, who were disgusted by the methods by which Lloyd George sought to win the war, ceased to make Labour merely a party of working-class men and trade unionists.

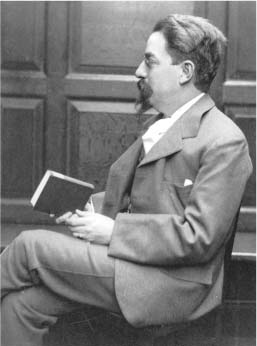

The author of Clause IV, Sidney Webb.

The consequence was the adoption at Nottingham of Clause IV of the Labour Party’s constitution. The clause, which framed the aims and values of the party, was drafted by Sidney Webb (1859–1947), the Fabian Society thinker, a co-founder of the London School of Economics and an advocate of schemes for ‘national efficiency’. It committed Labour for the first time to an explicitly socialist ideology – to secure for all workers ‘the common ownership of the means of production and the best obtainable system of popular administration and control of each industry and service’.

THE RISE OF THE LABOUR MOVEMENT

1834 The Tolpuddle Martyrs, six agricultural workers in Dorset who covertly form a union, are convicted of making illegal secret oaths and transported to Australia for seven years. Following a public outcry, their sentence is cut to four years.

1868 The Trade Union Congress meets for the first time, in Manchester.

1892 Keir Hardie is elected an independent Labour MP for West Ham South; he loses his seat in 1895.

1893 Hardie co-founds the Independent Labour Party (ILP) in Bradford.

1900 The Labour Representation Committee (LRC) is founded at the Memorial Hall, Farringdon Street, by the ILP, the Fabians, the (Marxist) Social Democratic Federation and trade unions.

1903 One hundred and twenty-seven unions, with 847,000 members, are affiliated to the LRC.

1901 In the Taff Vale verdict the Law Lords rule that the unions may be financially liable for the cost of their strike action.

1906 The LRC wins twenty-nine seats in the general election and is renamed the Labour Party. The Trades Disputes Act reverses the Taff Vale decision and frees the unions from corporate liability for strike action.

1914 The Labour Party supports the war effort. Opposing it, Ramsay MacDonald resigns as chairman of the parliamentary Labour Party. The ILP also opposes the war.

1915 Labour’s new leader, Arthur Henderson, enters the war coalition Cabinet.

1924 Ramsay MacDonald becomes the first Labour prime minister, but his minority administration loses power within ten months.

1926 The General Strike is called in defence of miners’ demands: it is called off after ten days.

1927 The Trades Disputes Act makes ‘sympathetic strikes’ illegal.

1929 Labour is the largest party in the general election and forms a minority administration.

1931 The Labour government breaks up over whether to address the financial crisis with budget cuts. Expelled from Labour, MacDonald stays on as prime minister until 1935 in a coalition with the Conservatives.

1932 The ILP disaffiliates from the Labour Party.

1940 Labour joins Winston Churchill’s wartime coalition, with Clement Attlee as deputy prime minister.

1945 Labour wins the July general election by a landslide.

1951 Labour loses the general election despite winning more votes: Churchill returns as Conservative prime minister.

1964 Labour wins the general election after thirteen years of Conservative rule: Labour leader Harold Wilson will serve three terms as premier (1964–66, 1966–70 and 1974–76).

1979 Margaret Thatcher defeats Labour prime minister Jim Callaghan in the general election; Labour suffers further election defeats in 1983, 1987 and 1992.

1995 Tony Blair, the architect of ‘New Labour’, repeals Clause IV.

1997 Labour returns to government after eighteen years in opposition, defeating John Major’s Conservatives in a landslide, and remains in office until losing the 2010 general election.

What this phrase meant in practice was open to interpretation. It could involve the state’s nationalization of private assets, or it could involve a ‘syndicalist’ approach in which various affiliations – whether trade unions, guilds or workers’ co-operatives – effectively determined productivity, pay and conditions. All that was certain was that it intended to spell bad news for private enterprise. In the event, nationalization proved to be the favoured method, although the unions were appeased and consulted as part of a corporatist approach to economic planning.

Common ownership was not advanced during Labour’s first two brief spells in government, in 1924 and 1929–31, under Ramsay MacDonald. There was neither the parliamentary majority nor the will to push forward the principles of Clause IV. This changed with the massive election victory won by Labour in 1945, after which Clement Attlee’s government nationalized the ‘commanding heights’ of industry – including coal, iron and steel, gas, electricity, telecommunications, aviation, road haulage and the railways. This proved to be the apex of the movement for state control.

An attempt to amend Clause IV was defeated in 1959, but the Labour Left’s efforts to nationalize Britain’s top twenty-five companies in the 1970s were resisted by the party leadership. Thereafter, the most explicitly socialist commitments were made in the 1983 manifesto, and their overwhelming rejection by the electorate began a process of retreat from this form of state control. Its last rites were symbolically read in 1995 when Tony Blair secured the repeal of Clause IV and its substitution with a more anodyne form of words:

The Labour Party is a democratic socialist party. It believes that by the strength of our common endeavour we achieve more than we achieve alone, so as to create for each of us the means to realise our true potential and for all of us a community in which power, wealth and opportunity are in the hands of the many, not the few, where the rights we enjoy reflect the duties we owe and where we live together freely, in a spirit of solidarity, tolerance and respect.