BRITAIN’S NATIONAL BROADCASTING CORPORATION

The BBC was the world’s first regular television broadcaster and is still the world’s largest broadcasting corporation. Even aside from its international reach and reputation, its influence on the knowledge, culture and shared experiences of the British people is beyond calculation.

It started in 1922 as a private enterprise, the British Broadcasting Company Ltd. Its major shareholders were six wireless-set manufacturers, including the business of the pioneer of the technology, Guglielmo Marconi, and British subsidiaries of the American-owned General Electric Company. They hoped to sell more sets, a prospect likely to be achieved only if radio broadcasting was allowed to reach a substantial audience.

Regulating wireless telephony was the responsibility of the Post Office. It wanted to avoid the chaotic race to start up radio stations that had just occurred in the United States, where the result was congestion and interference on the airwaves, low-quality programme-making and bankrupt companies. As favouring the BBC seemed the perfect means of avoiding this outcome, the Post Office granted it the exclusive right to construct transmitters across the country from which to broadcast. It would receive half of the 10-shilling (50p) fee that the Post Office charged listeners for their annual receiving licences.

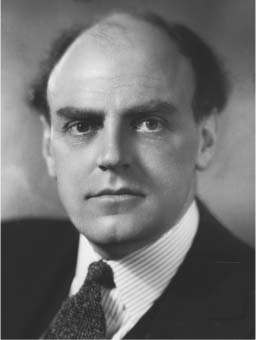

The BBC’s general manager, John Reith (1889–1971), had no background in broadcasting but demonstrated an unremitting determination to use what he described as ‘the brute force of monopoly’ as a power for moral and cultural enlightenment. He envisaged the BBC as bringing to homes across the country ‘all that was best in every department of human knowledge, endeavour and achievement’ in its mission to inform, educate and entertain. His first great test came in 1926 when the General Strike brought much of the country to a standstill and shut down the traditional Fleet Street newspapers. Reith resisted the efforts of some Cabinet ministers to commandeer the BBC for government propaganda, in the process enhancing the company’s reputation for independence.

From the BBC’s Royal Charter, 1927

Whereas it has been made to appear to Us that more than two million persons in Our Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland have applied for and taken out Licences to instal and work apparatus for . . . the purpose of receiving Broadcast programmes and whereas in view of the widespread interest which is thereby shown to be taken by Our People in the Broadcasting Service and of the great value of the Service as a means of education and entertainment, We deem it desirable that the Service should be developed and exploited to the best advantage and in the national interest . . . [by] a Corporation charged with these duties . . . [and] created by the exercise of Our Royal Prerogative.

At the same time, Parliament was considering the future of the medium. The Crawford Committee recommended revoking the BBC’s licence and transforming the company into a public corporation, guided by the responsibility to be a ‘Trustee for the national interest’. Stanley Baldwin’s Conservative government endorsed the Crawford Committee’s proposals, and on New Year’s Day 1927 the BBC was re-established by royal charter as the British Broadcasting Corporation. To avoid commercial advertising, the licence-fee model of funding was retained. There were already over 2 million receiving licences and it was clear millions more were on the way.

The new corporation was the state broadcaster, enjoying a monopoly of all output, with a board of governors nominated by the government. Nevertheless, it had operational and editorial independence. To minimize the risk that it would destroy competition from other forms of media or even peddle an agenda of its own, its news output was at first strictly limited. It was not permitted to broadcast news bulletins until 7 p.m. in order to avoid detracting from the newspaper market, the bulletins being strict summaries of news compiled from the press agencies. The emphasis was on avoiding contentious discussion and any analysis of current affairs.

Gradually, these restrictions were pruned down and lifted, although they shaped an approach that, during the 1930s, tended to shy away from the articulation of unorthodox views. Winston Churchill was among those who complained that he was not given airtime to voice his opposition to the government’s appeasement policy. Critics detected a longer legacy from this period that was evident in the corporation’s deferential tone and failure to take risks. It was not until the 1960s that this broke down when the BBC was given a new direction by a modernizing director-general, Hugh Carleton Greene (the brother of the writer Graham Greene). The broadening appeal was not to everyone’s taste – the ‘Clean-Up TV’ campaigner, Mary Whitehouse, concluded that Greene was ‘more than anybody else . . . responsible for the moral collapse in this country’.

Sir John Reith, who took the BBC from a company to a corporation and served as its first director general from 1927 to 1938.

By then, the BBC was as much a television as a radio broadcaster. The prospect of television was loathed by Reith, a dour Presbyterian Scot who made even his radio announcers read the news in black tie. Nonetheless, it was during his tenure as director-general between 1927 and 1938 that the corporation adopted the medium. At 3 p.m. on 2 November 1936, Leslie Mitchell announced live to camera, ‘This is the BBC Television Station at Alexandra Palace,’ and Britain’s fascination with ‘telly’ began.

The first TV programmes were broadcast using two different formats one after the other, John Logie Baird’s mechanical electronic system, followed by the wholly electronic Marconi–EMI technology. The latter’s better picture quality and scope for future improvement quickly won the day. Because of the cost and limitations of early television sets the audience was small and based in the South-East, where 20,000 sets could receive the BBC’s twenty hours a week of programmes in 1939 until the service was shut down for the war. Broadcasting resumed in 1946, and its popularity was hugely boosted by its coverage of Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation in 1953.

Since then, the BBC’s charter has been renewed and it has remained a public service broadcaster, funded by the licence fee. Despite the best efforts of the welfare state advocate, William Beveridge, its monopoly proved indefensible. In 1954, Winston Churchill’s government secured the passage of the Television Act. It permitted commercial television, with various regional companies – operating under fixed-term franchises – producing their own material under the umbrella of Independent Television (ITV) and its regulator, the Independent Television Authority. The development was initially opposed by the Labour Party, which believed greater choice would diminish quality. The viewing preferences of Labour’s core voters forced an urgent rethink.

The BBC responded with more channels, launching BBC2 in 1964 (which was the first to broadcast in colour, in 1967) and rearranging its radio output into four (later five) national stations plus various regional stations. Further independent competition came from Channel 4 in 1982 and Sky satellite television in 1989. With the advent of the internet, the 1990s brought a new threat that the corporation decided to embrace, first with its own news website and, in 2007, by streaming its programmes online. Whether its unique funding formula will survive indefinitely remains a matter for debate, although remarkably the BBC’s listening and viewing figures have held up surprisingly well, despite the swelling number of competing channels and alternative entertainments on offer. Its modern embrace of popular tastes and periodic vulgarity would have horrified Reith, yet it has still broadly tried to honour his guiding principles – if not his style – to inform, educate and entertain.