There was a widespread fear that the monarchy might not survive the abdication of King Edward VIII. Despite all the dramas of peace and war over the centuries, the prime minister, Stanley Baldwin, thought it appropriate to tell the House of Commons: ‘No more grave message has ever been received in Parliament.’

In the seventeenth century Charles I had been executed and his son, James II, had fled into exile. Thereafter, Britain had experienced almost 250 years of constitutional monarchy, its kings and queens having died while still in office. The very idea that Edward VIII (1894–1972) should throw his throne away – within a year of ascending to it – for the love of Mrs Wallis Simpson (1896–1986), a woman who was an acquired taste, dumbfounded many. As Edward’s mother, Queen Mary, later told him, it remained ‘inconceivable to those who had made such sacrifices during the war that you, as their King, refused a lesser sacrifice’.

Having succeeded his widely respected father, George V, in January 1936, Edward appeared to be an affable, handsome, modern-minded monarch. Yet behind the scenes, his flippant attitude to his duties and his growing attachment to Wallis Simpson caused consternation among those more closely acquainted with him. The general public knew nothing of this until 1 December, when the bishop of Bradford chose the occasion of a diocesan conference to lament the king’s failure to recognize that he was in need of God’s grace. Reluctant to engage in self-imposed censorship any longer, the press regarded this as the moment to break a story in Britain that was already filling the column inches of the foreign press.

Edward hoped he could marry his twice-married American lover and retain his throne. The Church of England, of which he was supreme governor, forbade a church wedding to divorced persons whose former spouses were still alive. Inconveniently in Mrs Simpson’s case, she had two living ex-husbands. It was a difficult situation, which, whatever the state of popular opinion, might have been smoothed if only the Church and the political Establishment had wished to do their monarch’s bidding. Instead, they saw little in his private demeanour or public posturing to justify conniving in so controversial an action. The possibility that he might contract a morganatic marriage – whereby Wallis Simpson would become his wife but not queen and any children would not succeed to the throne – was effectively ruled out by Baldwin, who assured his king that Parliament would not agree to it.

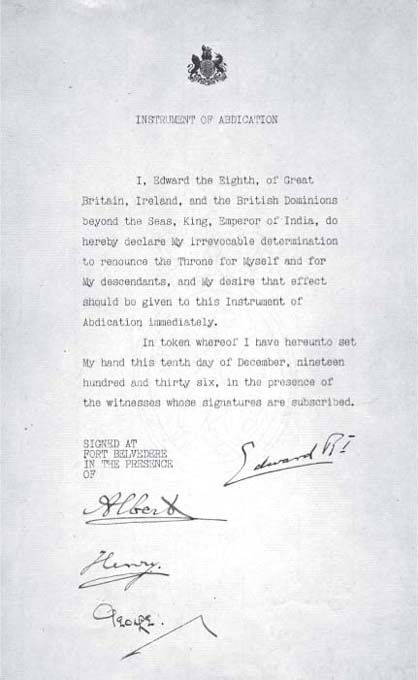

The Instrument of Abdication signed by Edward VIII and his three brothers – Albert, duke of York (thereafter George VI), Henry, duke of Gloucester and George, duke of Kent.

1894 Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David is born in Richmond, Surrey.

1907 Aged thirteen, Edward is sent to naval college.

1910 Death of Edward VII and accession of George V.

1911 Edward is invested as Prince of Wales.

1912 Edward studies – briefly – at Magdalen College, Oxford.

1919–35 Edward undertakes sixteen tours to various parts of the British Empire.

1933 Edward begins his affair with Wallis Simpson, an American divorcee.

1936 Edward ascends the throne only to abdicate it when the government effectively prevents him from marrying Wallis and remaining king.

1937 Accorded the titles duke and duchess of Windsor, Edward and Wallis marry at the Château de Candé in France. They go on to tour Germany as guests of Hitler.

1940 After undistinguished and potentially compromising war service, the duke (with the duchess) flees France for Lisbon. The duke is made Governor of the Bahamas for the duration of the war, largely to get him out of the way of trouble.

1945 The duke and duchess settle in Paris, supported by a government allowance and an exemption from French income tax.

1951 The duke’s largely ghost-written autobiography, A King’s Story, is published.

1972 The duke of Windsor dies of cancer and is buried with other members of the royal family at Frogmore, Windsor. The duchess becomes increasingly reclusive and bed-ridden.

1986 The duchess of Windsor dies at her home in the Bois de Boulogne, Paris.

As prime minister, Baldwin was the decisive figure throughout the crisis. He tightened the screw by insisting that the government would resign if the king persisted with his marriage plans. Baldwin had even taken the precaution of securing the Labour opposition’s word that it would refuse to form a government in this eventuality. Alternative politicians lacked either the credibility or a parliamentary majority to carry out the king’s wishes. If Edward did not back down, his realm would have no functioning government.

He pleaded for time, but Baldwin insisted on a speedy decision in order to prevent the country becoming divided. His Majesty’s own govern ment refused him permission to broadcast directly to his people. Outmanoeuvred, he realized that further prevarication was useless and chose love over duty.

Edward signed the Instrument of Abdication on 10 December. His brothers also appended their signatures to it, including his successor, Prince Albert, duke of York, who signed under his first name, but who reigned as George VI. An Act of Parliament was rushed through Westminster the following day, giving the abdication document legal effect. Only with the deed done was Edward permitted to broadcast a farewell to his former subjects and to pledge allegiance to his brother, who, as Edward rather pointedly observed, enjoyed the ‘matchless blessing enjoyed by so many of you and not bestowed on me – a happy home with his wife and children’.

Indeed, the new king’s family, in particular his wife, Queen Elizabeth, and elder daughter, the Princess Elizabeth, were to prove a great support to George VI, a shy, stuttering man who had never wanted his brother’s throne but was determined to overcome his limitations in order to do the duty Edward shirked. Created duke of Windsor, Edward married Wallis in June 1937 in a private ceremony, attended by only a few friends, in France, where they were to spend much of the rest of their lives. A perspective on their subsequent level of contentment was eventually offered by Wallis when she confided: ‘You have no idea how hard it is to live out a great romance.’

Nothing in Edward’s subsequent conduct contradicted the suggestion that the Instrument of Abdication was anything other than a godsend for the monarchy and the British realm.