THE APPEASEMENT OF NAZI GERMANY

By the early 1930s, Britain’s sense of relief at having been on the winning side in the Great War had been swamped by a solemn recognition of the scale of sacrifice involved. Economic depression and the rise of fascism in Europe reinforced the feeling of futility. Amid a growing mood of anti-militarism, many Britons, especially on the Left, looked to the League of Nations (the forerunner to the United Nations) to replace old balance-of-power politics with a ‘collective security’ approach to problems.

The revulsion at the prospect of rearmament and a dislike of traditional ‘sabre-rattling’ made the British government’s appeasement of Adolf Hitler’s regime both possible and, until late in the day, popular. Diplomatic measures to restrict German aggression had been framed by the 1919 Treaty of Versailles, but by the mid-1930s the agreement was widely criticized as one of the causes of Germany’s lurch into fascism. Neither Britain nor France chose to uphold the treaty’s clauses – not when Hitler remilitarized the Rhineland in March 1936, nor when he annexed Austria two years later. The newsreels showing jubilant crowds welcoming the German army into these areas effectively blunted claims that Hitler’s actions lacked the popular support of the very groups they affected.

Hitler’s efforts to annex the Sudetenland – the German-speaking region of Czechoslovakia – was far more contentious. Unlike London, Paris had an agreement with Prague to defend the territorial integrity of Czechoslovakia. Although the Sudetenland’s German-speaking majority appeared to welcome German annexation, permitting the redrawing of the boundary would effectively make the remaining Czechoslovak state strategically vulnerable should Hitler threaten it at a later date.

Neville Chamberlain (1869–1940), who had been prime minister since May 1937, was determined to take the diplomatic lead in order to permit the transferral of the Sudetenland to Germany in an orderly and peaceful manner that did not provoke Franco-German, and possibly European-wide, war. He flew to Germany to negotiate directly with Hitler, whose stated intention was to invade the Sudetenland regardless of the consequences. Chamberlain thought his efforts had failed, until, on 28 September 1938 – with Hitler’s troops poised to cross the Czech border – he was summoned to a conference the following day at Munich. There, he met Hitler, the French prime minister Edouard Daladier, and the Italian fascist leader Benito Mussolini. Together, they agreed that Germany could annex the Sudetenland without fear of retaliation. Deserted by her allies (and not even invited to the conference), the Czechs were forced to acquiesce in the carve-up of their country.

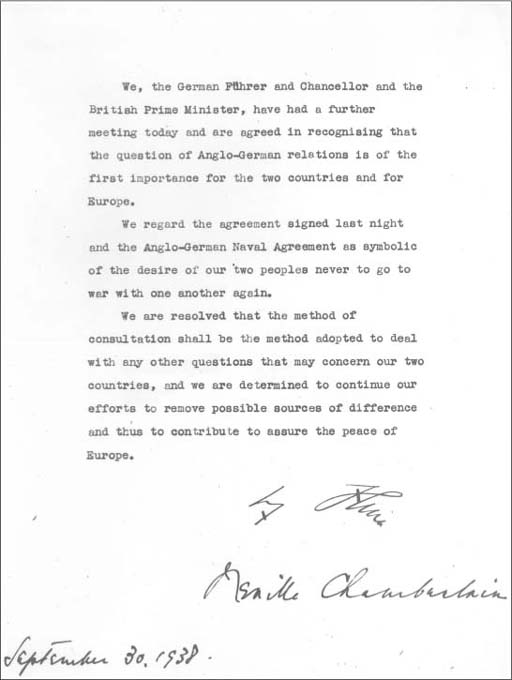

The Munich ‘piece of paper,’ signed by Adolf Hitler and Neville Chamberlain, pledging the peaceful resolution of Anglo-German disputes.

Believing world war had been averted, Chamberlain returned to Britain on 30 September and received a hero’s welcome. He believed his great personal achievement during the negotiations had been to come back with a piece of paper (which he held up to the cheering crowds at Heston aerodrome) that he had persuaded Hitler to sign. In this note, the German Führer and the British prime minister renounced war and determined to resolve their future differences purely through diplomacy.

This proved to be the zenith of Britain’s appeasement policy. Six months later, and without warning, Hitler invaded the rump Czechoslovakian state that Chamberlain’s diplomacy had helped render virtually defenceless. Scrambling to limit further Nazi expansion in Central and Eastern Europe, Britain rushed to offer Poland a guarantee of military support in the event of German invasion. On 3 September 1939, this agreement brought Britain (joined by France) into all-out war with Germany for the second time in twenty-one years.

OPPOSITE: The Munich ‘piece of paper,’ signed by Adolf Hitler and Neville Chamberlain, pledging the peaceful resolution of Anglo-German disputes.

‘Here is the paper which bears his name upon it as well as mine’ – Neville Chamberlain tells the crowds greeting him at Heston aerodrome that Hitler has given him his word at Munich. On the far left of the picture, a tall man is observing intensely. He is the foreign secretary, Lord Halifax.

14 March At Hitler’s prompting, Slovakia’s provincial assembly declares independence from Czechoslovakia.

15 March Germany invades the remaining rump of the Czech state.

22 March Germany annexes Memel from Lithuania.

28 March–1 April The Spanish Civil War ends in victory for Franco’s German- and Italian-backed Nationalists.

31 March Britain announces it will guarantee Poland’s sovereignty against attack.

7 April Italy invades Albania.

22 May Germany and Italy agree a ‘Pact of Steel’.

24 May The Cabinet agrees to explore terms for a military pact with the Soviet Union.

23 August The Molotov–Ribbentrop non-aggression pact is signed between Germany and the Soviet Union.

24 August Parliament is recalled. The Emergency Powers Act is rushed through.

25 August The British guarantee regarding Poland’s security is given legal status.

31 August The Royal Navy is mobilized. The evacuation of children from London begins.

1 September Germany invades Poland.

3 September At 9 a.m. Britain sends Germany a two-hour ultimatum to begin withdrawing from Poland. When no undertaking is received, at 11 a.m. Britain declares war on Germany. At 11.15 a.m. Neville Chamberlain broadcasts to the nation, announcing that it is at war. At 5 p.m. France declares war on Germany.

Chamberlain’s agreement at Munich came to be seen as a betrayal of the democratic Czechoslovakian state in a desperate – and ultimately futile – effort by Britain to save herself from war. Indeed, appeasing Hitler at Munich only appeared to give the Führer the wrong impression that he could continue with the forcible annexation of his neighbours with impunity. These ‘lessons of Munich’ influenced post-war British and American foreign policy, encouraging a more bellicose attitude towards dictatorial regimes, with varying levels of success, including against the Soviet Union in the Cold War, Egypt’s President Nasser in the 1956 Suez Crisis and Iraq’s Saddam Hussein over his invasion of Kuwait in 1990.

A rival interpretation of Chamberlain’s actions at Munich eventually developed in which some historians argued that appeasement saved Britain from fighting a war in 1938 for which she was militarily ill-prepared. This was true, although it also bought Germany eleven months in which to further her own rearmament programme as well. For instance, the Munich agreement delivered into the hands of Hitler’s Reich the Skoda armaments factory in the Sudetenland, whose output between October 1938 and September 1939 was almost equal to all British armaments factories put together.

Nevertheless, Chamberlain’s aim at Munich was to prevent, rather than defer, war. As his adviser Horace Wilson admitted in 1962: ‘Our policy was never designed just to postpone war, or enable us to enter war more united. The aim of appeasement was to avoid war altogether, for all time.’ Chamberlain had said as much when he greeted the crowds on his return from Munich with his famously ill-fated comment that he hoped he had brought home ‘peace for our time’.