The pavement of Route 66 begins in Chicago, but the idea began here in Oklahoma. When the Joint Board of State and Federal Highway Officials was establishing the system of numbered routes in the 1920s, Tulsa businessman Cyrus Avery envisioned a major artery passing right through the heart of his own state of Oklahoma. And he worked long and hard to make it a reality.

It is no accident that Route 66 cuts such a long, sweeping swath directly through the center of Oklahoma. If you look at a map of the United States and draw a more or less direct line from Chicago to Los Angeles, that path will miss the state of Oklahoma entirely. Even allowing for the curvature of the earth not apparent in such a map, the most logical path for such a highway would pass through very little of Missouri, none of Oklahoma, and directly through the heart of Kansas. Indeed, if the highway had been plotted along already-established trails through Middle America, such as the Santa Fe Trail, that path, too, would have made Kansas (but not Oklahoma) a prominent part of the route.

However, U.S. 66 was deliberately calculated to take traveling Americans through Cy Avery’s stomping grounds. He reasoned correctly that such a highway would put Oklahoma “on the map” and cause lots of travel-related dollars to be spent all across the state.

This placement of the highway became somewhat fortuitous when the Dust Bowl years of the 1930s imposed such a hardship on Oklahomans that many of them fled the region for California. Then, all of the surrounding roads became tributaries, adding their flow to the Mother Road and inspiring the dark Grapes of Wrath imagery, which the highway still evokes today.

One of the reasons Oklahoma needed to be put on the map, more so than some other states, has to do with its unique past. For many years, the area had been designated as Indian Territory and was home to tribes that had participated in the forced march, known as the Trail of Tears, to the region. It was only in 1907 that Oklahoma attained statehood; therefore, it had been a state for less than two decades by the time the interstate highway system was established in the ’20s. By traveling through the state, however, Americans could see for themselves that Oklahoma was no longer a “territory,” nor was it as primitive as that word implied. Route 66, then, would be Oklahoma’s ticket to joining the twentieth century as a full partner.

![]() If you’ve just traveled the old highway’s short course through Kansas, you’ll enter Oklahoma by moving south on U.S. 69. Like the small section of Kansas you’ve left behind, this part of Oklahoma is mining country, and there’s very little to differentiate it at first. The changes, however, will appear soon.

If you’ve just traveled the old highway’s short course through Kansas, you’ll enter Oklahoma by moving south on U.S. 69. Like the small section of Kansas you’ve left behind, this part of Oklahoma is mining country, and there’s very little to differentiate it at first. The changes, however, will appear soon.

Oklahoma is very 66-friendly, which fits its unofficial status as the birthplace of Route 66. By that, I mean you will have less difficulty following the old route here than you would probably have elsewhere. Official state maps, distributed free by the Oklahoma Department of Transportation, have for years now clearly marked the path of Historic Route 66. Not only that, but one of the later alignments of old 66, as it existed at the time of bypassing by the turnpikes, has been designated as Oklahoma 66. That means you can follow the double sixes almost continuously across the state. Keep in mind, of course, that the alignment marked as State Highway 66 is only one of many that the route followed over the years. As always, observation and exploration are your tickets to maximum enjoyment.

Less than five miles into Oklahoma, you’ll come to the Route 66 community of . . .

QUAPAW

The village of Quapaw, about four miles from the Kansas state line, boasts a few buildings with murals—faded though they are—painted on them, which one of the locals told me were created in the 1970s. Keep alert as you cruise through town.

Commerce, Oklahoma. GPS: 36.93323,-94.87755

COMMERCE

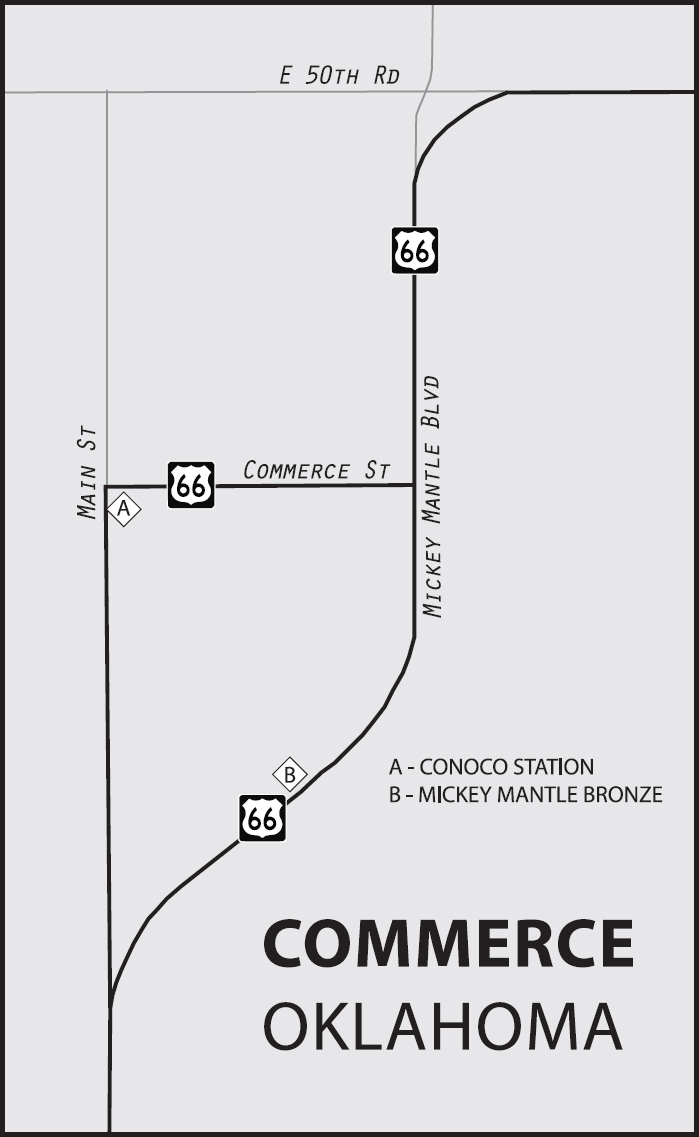

Commerce is the boyhood home of baseball star Mickey Mantle, and gave him the nickname “Commerce Comet.” The main drag (old 66 bypass) has been re-named Mickey Mantle Boulevard. At Mickey Mantle’s childhood home (319 S. Quincy St.) is a metal-sided barn on the property full of dents where Mickey practiced his hitting. A few years ago, there was a plan to build a Mickey Mantle museum in town, but those plans have been abandoned. I spoke with someone involved in the project who told me it had been decided that such a museum would need to be located in a larger community (no decision as to where). On June 12, 2010, a large bronze statue of The Commerce Comet (420 D St.) was unveiled in front of Mickey Mantle Field on the south side of town.

Commerce, Oklahoma. GPS: 36.93323,-94.87755

Mickey Mantle Field, Commerce, Oklahoma. GPS: 36.92480,-94.87191

Originally, Route 66 passed along the town’s main business district on Commerce Street. Today, near the west end of Commerce Street, there is an old cottage-style gasoline station (101 S. Main St.) with a small collection of petroliana and such.

MIAMI

Named for an American Indian tribe and pronounced “my-AM-uh,” this was at one time informally known as Jimtown, after four farmers named Jim in the area.

The jewel of Miami is by all accounts the Coleman Theatre (103 N. Main St.). Originally designed in Italianate style, during construction it was converted to Spanish Mission Revival, resulting in a unique piece of architecture. The theater opened in April of 1929, just six months before the beginning of the Great Depression. The Coleman was on the Orpheum Vaudeville circuit and saw the likes of Will Rogers, Tom Mix, the Three Stooges, and Sally Rand as performers. Today, free guided tours are available.

MIAMI ATTRACTIONS

For regional history, visit the Dobson Museum (110 A St. SW), which includes American Indian artifacts, mining items, and other articles relating to the area’s early settlement. There is also an extensive collection of Texaco-related materials.

A Marathon Oil Gasoline Station (331 S. Main St.) built in 1929 is thought to be one of the oldest of its kind still standing.

Also in Miami is Route 66 Vintage Iron (128 S. Main St.), a motorcycle museum with what they tout as one of the largest collections of Steve McQueen-owned gear.

In the spirit of the Mother Road, the citizens added a reproduction of an early archway over the road welcoming travelers to downtown Miami.

The Coleman opened its doors in 1929, at the threshold of the Great Depression. Miami, Oklahoma. GPS: 36.87648,-94.87755

![]() On the southern outskirts of Miami, you can still find some portions of old 66 that are even older than the route itself (pre-1926). In the vicinity are some one-lane-wide sections of concrete roadway that were paved in the early ’20s. It’s said that money was tight, and they only had half the amount needed to do the job completely. Rather than cover half the mileage, the decision was made to pave the full distance, but at half the normal width. This meant—and of course it still means today—that driving the road requires extreme caution, particularly where visibility is short. Just move your passenger-side wheels off onto the ample shoulder when necessary. To locate this section, just continue straight (on Main Street) past the Steve Owens Boulevard intersection, then turn right when you can no longer continue straight ahead. The one-lane section of 66 will demonstrate very clearly that early highway alignments were constructed with a considerable number of ninety-degree corners. The removal of such harsh turns by re-routing was a major thrust throughout the country during the 1930s.

On the southern outskirts of Miami, you can still find some portions of old 66 that are even older than the route itself (pre-1926). In the vicinity are some one-lane-wide sections of concrete roadway that were paved in the early ’20s. It’s said that money was tight, and they only had half the amount needed to do the job completely. Rather than cover half the mileage, the decision was made to pave the full distance, but at half the normal width. This meant—and of course it still means today—that driving the road requires extreme caution, particularly where visibility is short. Just move your passenger-side wheels off onto the ample shoulder when necessary. To locate this section, just continue straight (on Main Street) past the Steve Owens Boulevard intersection, then turn right when you can no longer continue straight ahead. The one-lane section of 66 will demonstrate very clearly that early highway alignments were constructed with a considerable number of ninety-degree corners. The removal of such harsh turns by re-routing was a major thrust throughout the country during the 1930s.

NARCISSA–AFTON

Between Narcissa and Afton is another section of the one-lane 66. To access it, turn right onto a street called E. 200 Road. However, once you’ve explored this, you might want to backtrack a bit on the newer alignment, which passes the former site of Buffalo Ranch (21600 U.S. 69). Buffalo Ranch was a good old-fashioned “tourist trap” featuring trained animals (technically American bison), plus the requisite curio shop, etc. The ranch itself has been replaced by a modern truck stop/convenience store, but they do maintain a few bison in an adjacent field.

One of my favorite Mother Road artifacts is here in Afton: the sign for the Rest Haven Motel. I hope it’s still there when you visit. A short distance away is the restored Afton DX Station and Packard showroom (12 SE 1st St.). The DX station is now an informal visitor center for Mother Roaders. Across the highway from the DX there used to be the World’s Largest Matchbook Collection. Unfortunately for all of us, that building burned down in the summer of 2003—no irony intended.

Afton, Oklahoma. GPS: 36.69496,-94.96099

This restored DX station serves as the de facto welcome center for the town of Afton, Oklahoma. GPS: 36.69444,-94.96211

Afton, Oklahoma. GPS: 36.68960,-94.97254

FURTHER AFIELD

Not far from Afton is Monkey Island, a peninsula community jutting into the Grand Lake o’ the Cherokees, and home to Darryl Starbird’s National Rod & Custom Car Hall of Fame Museum (55251 OK-85A). The collection features over forty street rods and other custom-built automobiles, as well as plenty of photographs and other memorabilia.

Just east of Afton you can take a side trip south on U.S. 59, across a portion of the Grand Lake o’ the Cherokees, to the community of Grove. Perhaps the most popular destination in town is Har-Ber Village (4404 W. 20th Rd.), described as one of the largest antique displays in the country. It features a reconstructed turn-of-the-century village with over 100 buildings, as well as a walking trail, herb garden, and other exhibits.

The town of Grove is also host to the Cherokee Queen I and II, a pair of paddlewheel riverboats that offer tourist excursions on the lake. In Grove’s Polson Cemetery (E. 340 Rd.) is the gravesite of General Stand Watie—the last Civil War Confederate General to surrender, and a full-blooded American Indian.

VINITA–WHITE OAK–CATALE

![]()

![]()

You’ll enter Vinita on Illinois Avenue/U.S. 69. Just continue following 69, which will include a left turn onto Wilson Street. West of town, when State Highway 66 splits away, begin following 66.

One of the oldest settlements in Oklahoma and originally called Downingville, the town was later re-named for Vinnie Ream (1850–1914), the sculptress who fashioned the life-sized image of Abraham Lincoln in the nation’s capitol. Vinita is also the birthplace of “Dr. Phil” McGraw of TV fame.

It was here in 1935 that Will Rogers had planned to attend the town’s first-ever annual rodeo. He died, however, in a plane crash at Point Barrow, Alaska, just weeks beforehand. Nowadays, that rodeo is known as the Will Rogers Memorial Rodeo, and it is held each August.

When the Lewis Motel in Vinita, Oklahoma, was demolished, this sign was sold off and now stands on a ranch in California.

Rogers somewhat facetiously called Vinita his “college town,” having attended a secondary school here.

VINITA ATTRACTIONS

The town’s self-guided Historic Homes Tour directs you to thirty-five turn-of-the-century houses built by the area’s founding families. You can get a guide at the Eastern Trails Museum (below). General visitor information is available by calling (918) 256-7133, where you can also get directions to the Barker Gang Gravesite and the Cabin Creek Civil War Battle Site.

The Eastern Trails Museum (215 W. Illinois Ave.) has a re-created post office, general store, printing office, and doctor’s office, as well as items representing American Indian history.

White Oak, Oklahoma. GPS: 36.61958,-95.26823

Clanton’s (319 E. Illinois Ave.) is a longtime eatery with lots of old photos lining its walls. The World’s Largest Calf Fry Festival & Cook-Off is held in Vinita each August, during which a full ton of the delicacies are consumed annually.

![]() West of Vinita, you’ll need to ignore the turnoff for U.S. 69 and continue straight ahead. Then begin following Oklahoma State Highway 66.

West of Vinita, you’ll need to ignore the turnoff for U.S. 69 and continue straight ahead. Then begin following Oklahoma State Highway 66.

On the highway west of Vinita, Oklahoma. GPS: 36.62709,-95.19836

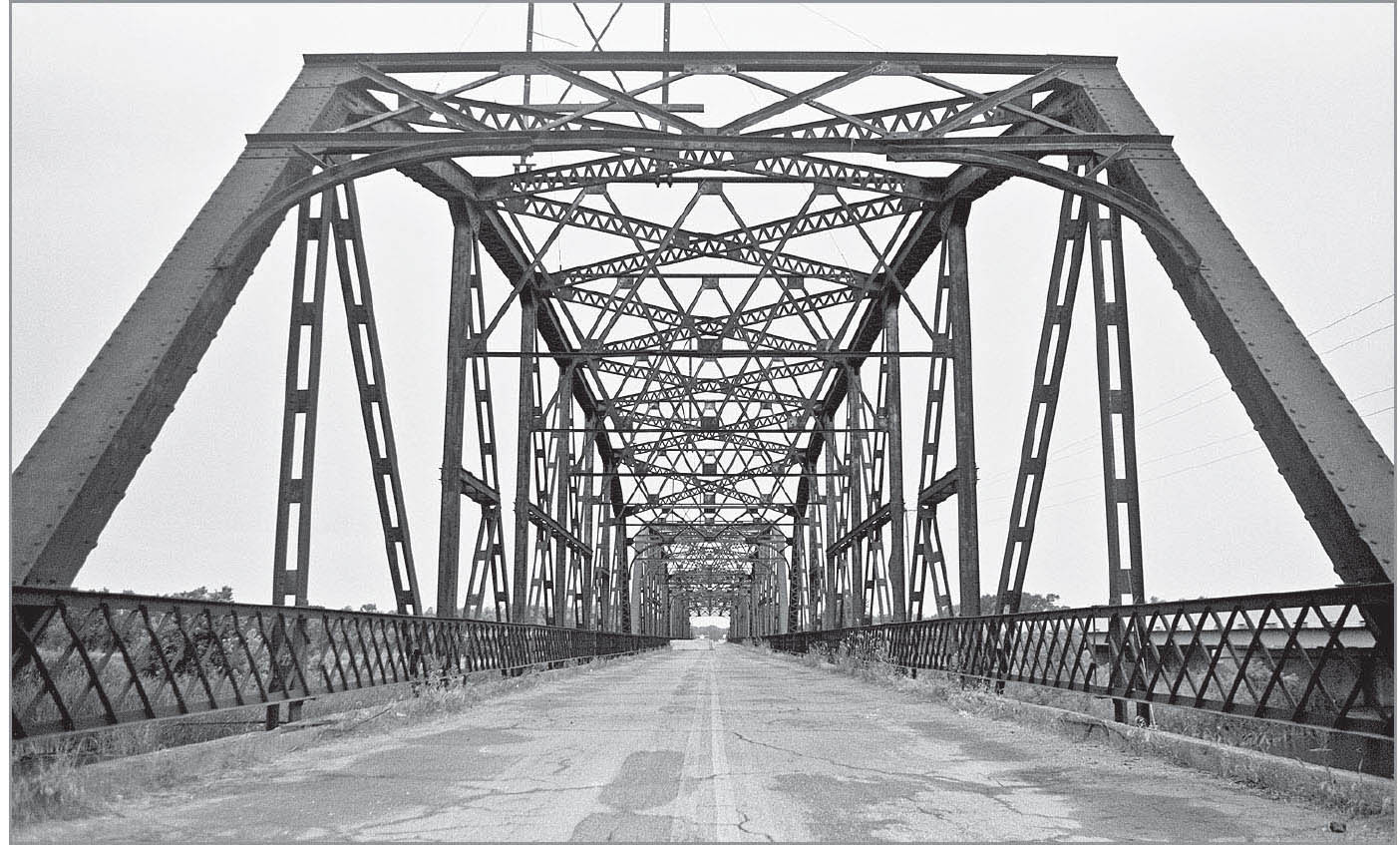

![]() Just before you arrive at the town of Chelsea, on the left side of the highway, you can take a turn onto a very old alignment of 66 across the Pryor Creek Bridge. If you continue on this route, you’ll pass through a few blocks of residences before being reunited with the more modern alignment, more or less in the central part of town, right beside what remains of the Chelsea Motel (N. Walnut Ave. and E. 1st St.), with its wonderful old sign.

Just before you arrive at the town of Chelsea, on the left side of the highway, you can take a turn onto a very old alignment of 66 across the Pryor Creek Bridge. If you continue on this route, you’ll pass through a few blocks of residences before being reunited with the more modern alignment, more or less in the central part of town, right beside what remains of the Chelsea Motel (N. Walnut Ave. and E. 1st St.), with its wonderful old sign.

CHELSEA

This community dates from 1882. The town includes an example of an underground pedestrian tunnel built to facilitate crossing the then-busy highway. A few miles to the south and west of Chelsea is the site of the first oil well in Oklahoma, which was established in 1889. Will Rogers’s sister lived here, whom he is said to have visited frequently.

Here in Chelsea is an original Sears Roebuck pre-cut house, purchased in Chicago in 1913 for $16 and delivered by railroad car. The Hogue House (1001 S. Olive St.) is the only known example west of the Mississippi that is still owned by descendants of the original purchaser.

This old bridge is on the east edge of Chelsea, Oklahoma. GPS: 36.53809,-95.41545

The modest Chelsea Motel had one of the nicest signs anywhere on Route 66. Chelsea, Oklahoma. GPS: 36.53777,-95.42652

BUSHYHEAD–FOYIL

![]()

![]()

Modern Oklahoma 66 bypasses Foyil, so I recommend slowing down to take the old alignment through town along Andy Payne Boulevard.

A Cherokee Indian chief lent his name to the community of Bushyhead.

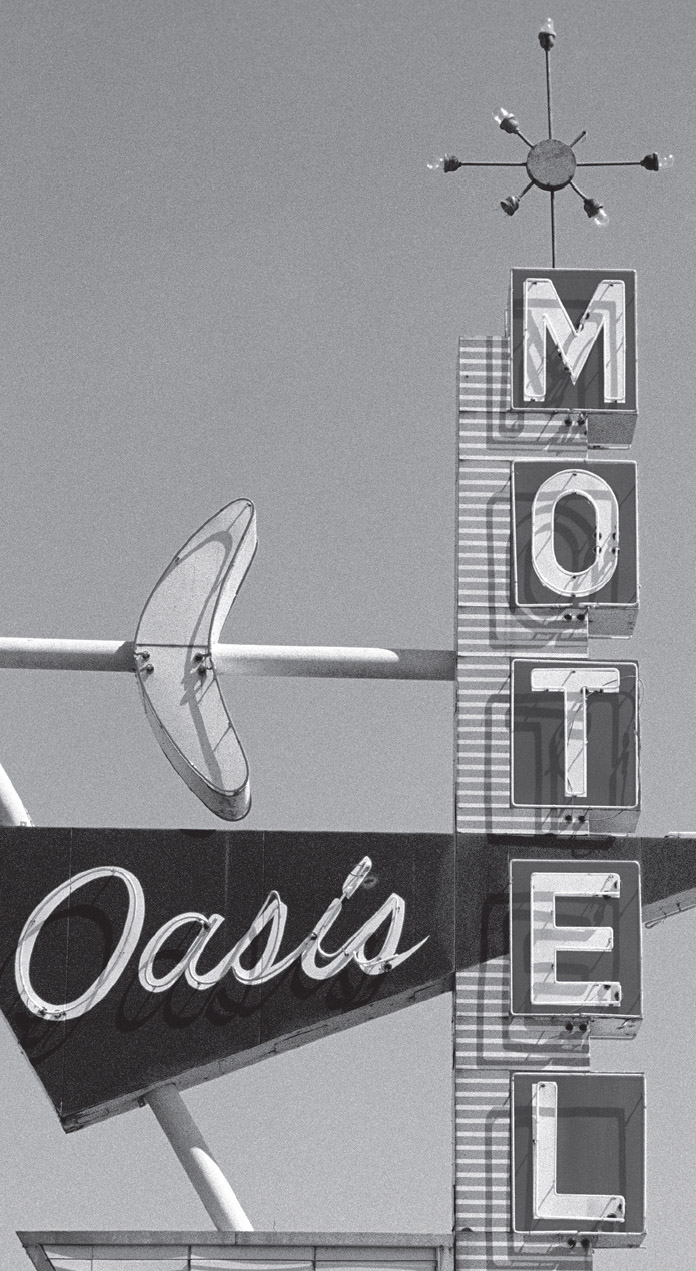

Andy Payne, winner of the 1928 Bunion Derby—a cross-country footrace organized as a wildly extreme promotional stunt—was from the Foyil area. There is a bronze statue of Andy Payne on an old alignment of 66 (Andy Payne Boulevard) at the far western edge of town.

Totem Pole Park, just outside Foyil, Oklahoma, is folk art at its very best. GPS: 36.43773,-95.44924

Foyil’s claim to fame today is that it is the home of Ed Galloway’s collection of concrete American-Indian-inspired structures, in what is commonly called Totem Pole Park (21300 E. Hwy 28A). This is truly a landmark, and a great old-fashioned roadside attraction to boot. Get there by leaving State Highway 66 and turning onto Highway 28A at the north edge of Foyil, and going about four miles east. The focal point of the collection is a ninety-foot-tall totem pole made of brightly painted concrete. Ed Galloway created this collection of structures in the post-war years (the main totem pole in particular bears a date of 1948) as an expression of his own creative impulses.

Fiddle House, Totem Pole Park, near Foyil, Oklahoma. GPS: 36.43773,-95.44924

Ed Galloway’s Totem Pole Park, east of Foyil, Oklahoma. GPS: 36.43773,-95.44924

Memorial to local hero Andy Payne, Foyil, Oklahoma. GPS: 36.42690,-95.52758

SEQUOYAH

Established in 1871, the name of this settlement was changed to Beulah in 1909, after the postmaster’s daughter. The name was changed back in 1913 to honor the famous Cherokee chief (also called George Guess) who developed the Cherokee alphabet. Remarkably, even the most advanced American Indian peoples had not developed written forms of their languages as late as the nineteenth century. Sequoyah, son of a Cherokee mother and a British trader named Nathaniel Gist, became convinced that the white men’s superior power and influence derived from their written language. He began developing a system of writing for the Cherokee people, believing that this would help them maintain their independence from the whites. He developed his syllabary, a system of eighty-six symbols denoting all of the syllables of the Cherokee language, in about 1821. The system was easy to learn and use, and by 1828 it was being utilized for the Cherokee Advocate newspaper.

CLAREMORE

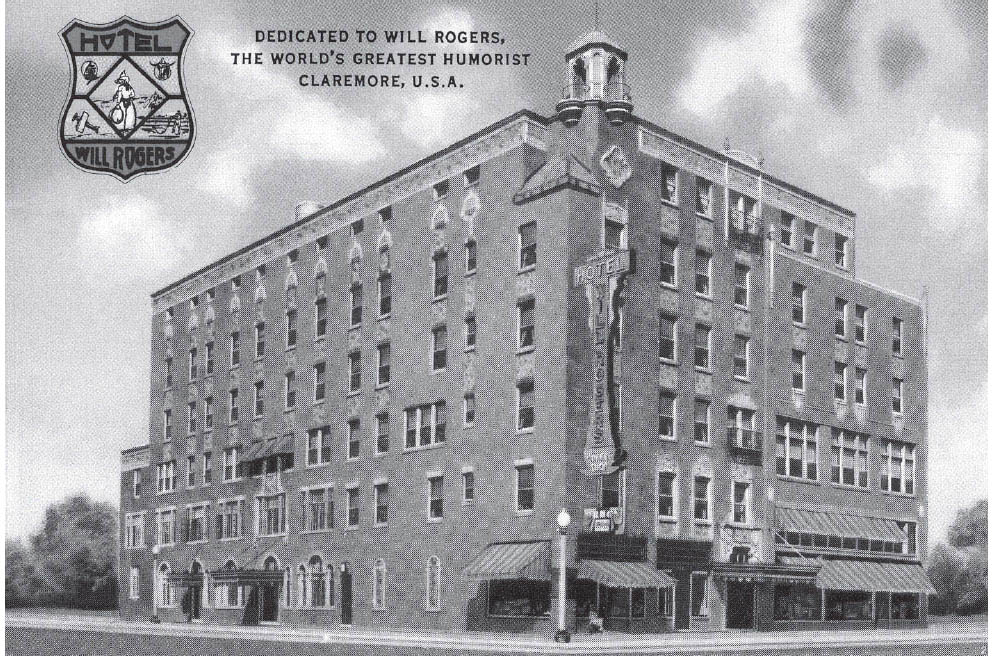

This is the county seat of Rogers County, which was named for Will Rogers’s father, Clem Rogers. Claremore was known in years past as a place for “taking the waters.” There was a well in town that produced a dark, malodorous substance called radium water (even though it contained no radium). This water was touted as being therapeutic for rheumatism and other ailments, and was a big selling point for staying at the Hotel Will Rogers (940 S. Lynn Riggs Blvd.), which was known for its baths. Lately, the hotel has been undergoing redevelopment, with business space for lease on the ground level.

As you enter Claremore from the east, there is an older alignment of Route 66 off to your right (J. M. Davis Boulevard) that is pretty easy to recognize. Along that stretch, on the left-hand side, is an old motel court now serving duty as an apartment complex called the Adobe Village (402 N. J. M. Davis Blvd.). It appears to be from the 1930s and bears a resemblance to the Alamo Courts chain, which could once be found around this part of the country.

CLAREMORE ATTRACTIONS

The most important thing to see in Claremore is, of course, the Will Rogers Memorial (1720 W. Will Rogers Blvd.). The museum, mausoleum, and grounds are beautifully designed, and they offer far too much to even begin to list. Rogers’s body was moved here in 1944, having been interred at Forest Lawn Cemetery in California from 1935 to 1944. Rogers had purchased the Claremore property with the intent of finally settling down permanently after his Hollywood career played itself out. Memorial services are held here annually on Rogers’s birthday, November 4.

Rogers’s most famous quote is: “I never met a man I didn’t like.” However, pithy statements were his stock-in-trade. There are thousands worth repeating, but he seemed to be speaking directly to people like you and me when he wrote in 1930: “But if you want to have a good time, I don’t care where you live, just load in your kids, and take some congenial friends, and just start out. You would be surprised what there is to see in this great Country within 200 miles of where any of us live. I don’t care what State or what town.”

A visit to the Will Rogers Memorial is well worth your time. Claremore, Oklahoma. GPS: 36.32085,-95.63217

The J. M. Davis Arms & Historical Museum (330 N. J. M. Davis Blvd.) is also a Claremore mainstay. Included in the thousands of firearms on display are weapons owned by the likes of Pretty Boy Floyd, Cole Younger, Pancho Villa, and other outlaw types. This is the world’s largest privately owned gun collection, with examples spanning six centuries of the gunsmith’s craft. Besides the guns, there are trophy heads, swords, musical instruments, American Indian artifacts, World War I posters, and even John Wayne movie posters.

The Claremore Museum of History (121 N. Weenonah Ave.) includes the actual “surrey with the fringe on top” made famous in the musical Oklahoma!, which was based upon Lynn Riggs’s play Green Grow the Lilacs. When the production premiered in the state in 1946, officials declared a state holiday.

On the campus of Rogers State University is Meyer Hall, which houses the Oklahoma Military Academy Museum (1701 W. Will Rogers Blvd.). The academy operated at this location from 1919 to 1971, when its functions were taken over by Claremore Junior College.

The Will Rogers Hotel still stands. GPS: 36.31279,-95.61588

Several Claremore buildings are listed on the National Register of Historic Places, including the former Will Rogers Hotel (940 S. Lynn Riggs Blvd.), the Belvidere Mansion (121 N. Chickasaw Ave.), and Meyer Hall (see above). The Belvidere Mansion is a restored pre-statehood Victorian home offering tours by costumed docents. It has a ballroom that occupies the entire third floor of the house.

The Swan Brothers Dairy Farm (938 E. 5th St.), operated by three generations of the Swan family since 1923, offers a store and tours.

Claremore holds a Bluegrass & Chili Festival in September and a Will Rogers birthday celebration each November.

FURTHER AFIELD

Northwest of Claremore via Highway 88 is the town of Oologah, Oklahoma. Here, overlooking Oologah Lake, is Will Rogers’s boyhood home, known as Dog Iron Ranch (9501 E. 380 Rd.). Access to the house, barn, petting zoo, and vintage films and newsreels are provided for your enjoyment. Rogers was born in this log-walled house in 1879. Today, there are 400 acres and a herd of longhorn cattle on the property. The town itself also has a bronze statue called The Cherokee Kid (Maple St. and Cooweescoowee Ave.) of its favorite son on horseback.

Belvidere Mansion, Claremore, Oklahoma. GPS: 36.31098,-95.60993

Much of the town’s turn-of-the-century downtown has been restored. The Bank of Oologah (Maple Street and Cooweescoowee Street), built circa 1906, boasts an authentic period interior and furnishings. Today, this bank is touted as having “closed during the Depression.” I’m sure that, at the time, no one considered this to be much of a selling point.

On the same corner is the Oologah Historical Museum (202 Cooweescoowee Ave. W), with Will Rogers photos and a complete doctor’s office on display. Miniatures of the Cherokee Kid statue in town (see above) are available in the museum’s gift shop.

VERDIGRIS–CATOOSA

The Port of Catoosa is the nation’s largest inland seaport, connecting Tulsa with the Mississippi River and the port of New Orleans. Here, the Arkansas River Historical Society Museum (5350 Cimarron Rd.) will educate you on the construction of the project. You might also want to visit the Catoosa Historical Society Museum (207 S. Cherokee St.), for a taste of the city’s heritage. Look for the Frisco caboose parked outside.

At the Cherokee Nation tourism bureau (777 W. Cherokee St.), you can get information about a plethora of significant sites across the state.

Roadside picnic area, Catoosa, Oklahoma. GPS: 36.19355,-95.73226

The D. W. Correll Museum (19934 E. Pine St.) houses a collection of rare and antique automobiles, rocks, gems, and other items in three separate buildings. Among the rare cars is a steam-powered Locomobile dating from 1898.

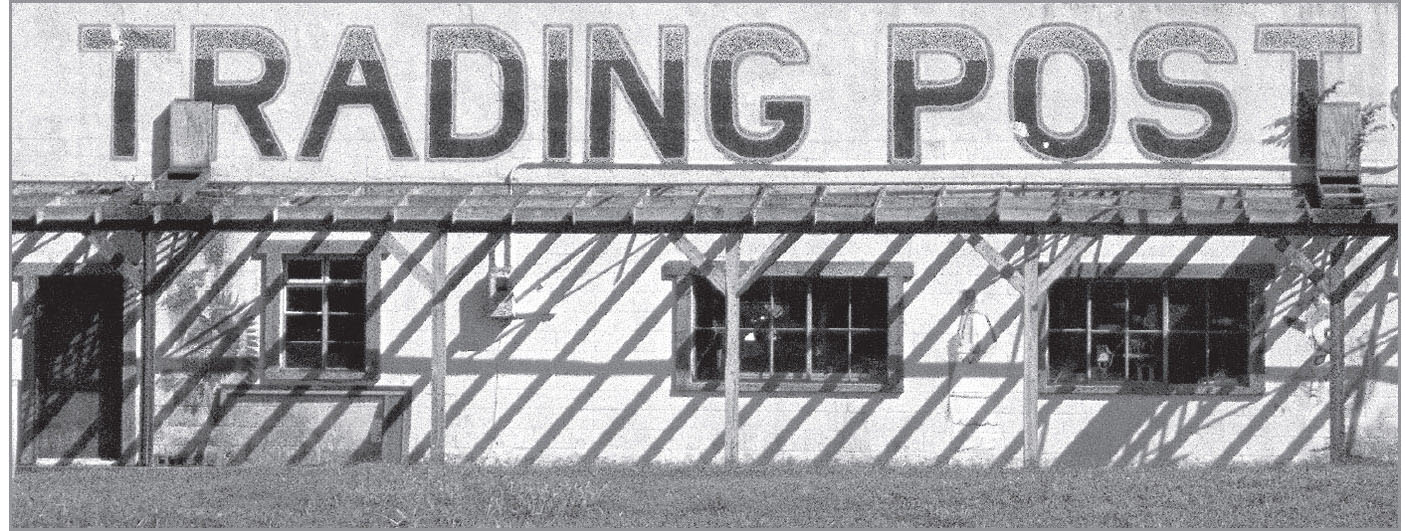

Near Catoosa is the Catoosa Whale (2600 Historic Rte. 66), an example of a small-scale mom-and-pop roadside attraction. Restored by volunteers in 2002, it is a large whale-shaped structure that is painted blue and sits in a small pond. In its heyday, visitors could enter the whale’s mouth and then either slide down a chute, which exits behind the whale’s ear, or dive off a small platform at the tail and into the surrounding swimming hole. Adjacent is a wooden “ark” that used to house a roadside menagerie. Just across the highway from them both is the former Arrowood Trading Post (2700 Historic Rte. 66).

Catoosa, Oklahoma. GPS: 36.19355,-95.73226

![]() Leave Catoosa on Cherokee Street. You’ll then veer left (south) onto S. 193rd East Avenue, then make a right turn onto 11th Street.

Leave Catoosa on Cherokee Street. You’ll then veer left (south) onto S. 193rd East Avenue, then make a right turn onto 11th Street.

LYNN LANE

This community appears east of Tulsa in my 1957 atlas, a little to the southwest of the current I-44/U.S. 412 junction, just inside Tulsa County. It has been swallowed by the expanding Tulsa city limits, which now run all the way out to the county line. The nearby Lynn Lane Reservoir (E. 21st St.) is a persistent reminder of the town’s existence.

TULSA

![]()

![]()

Enter Tulsa on 11th Street, which runs for several miles to very near the town’s center. A variation is to turn north at Mingo and go west on Admiral Place, which was the original alignment. That routing takes the traveler into the downtown area, just as all highways used to do. You would do well to explore downtown in either case.

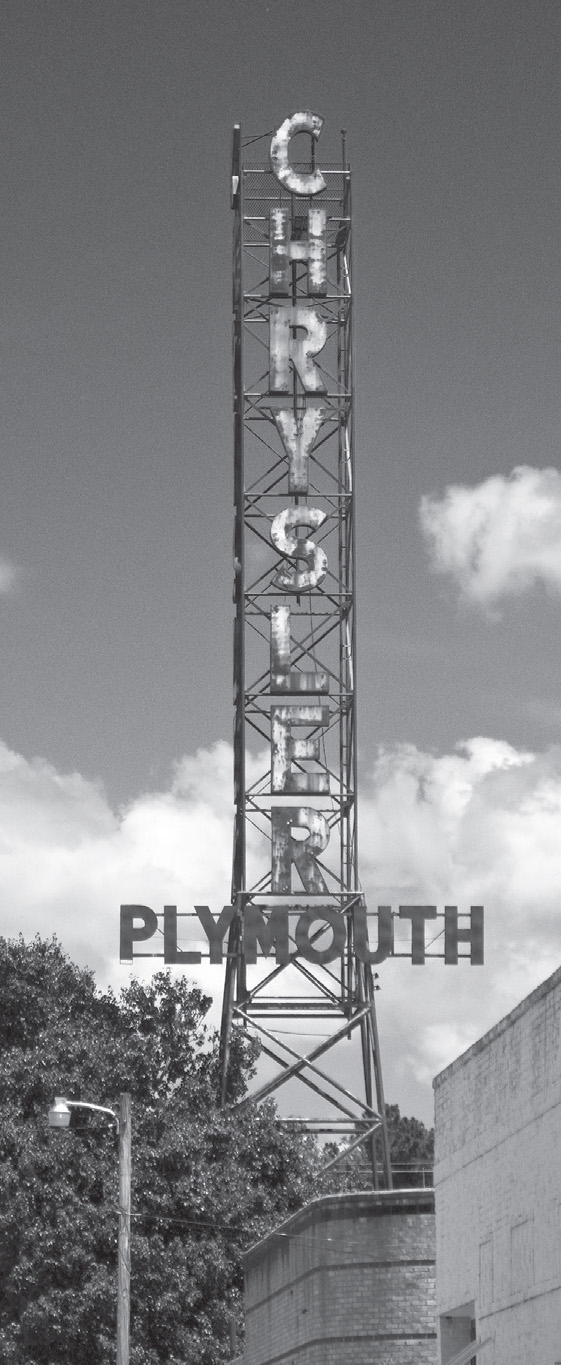

A city which owes much to the oil industry, Tulsa was also the home of Cyrus Avery, a man so instrumental not only in establishing Route 66, but also in routing it through his home state and town. Perhaps his strongest case was the presence of the 11th Street Bridge, now called the Cyrus Avery Route 66 Memorial Bridge, easily the best crossing of the Arkansas River at the time. Today that bridge has been converted to a Route 66 destination. The bridge itself is closed to traffic, and Cyrus Avery Centennial Plaza was added to its east end, including bronze sculptures.

Notorious outlaw Kate “Ma” Barker lived in Tulsa from 1930 to 1931. That was about the same time that Madison W. “Daddy” Cain bought a former garage and called it Cain’s Dance Academy, later to become Cain’s Ballroom (423 N. Main St.) and a thriving center for what later came to be called Western Swing.

In 1938, Tulsa gave birth to the Society for the Preservation and Encouragement of Barbershop Quartet Singing. Now headquartered in Kenosha, Wisconsin, as the Barbershop Harmony Society, the organization has thousands of chapters coast-to-coast and internationally. There are two quartets calling Tulsa home: the Tulsa Tones and Sound Decision.

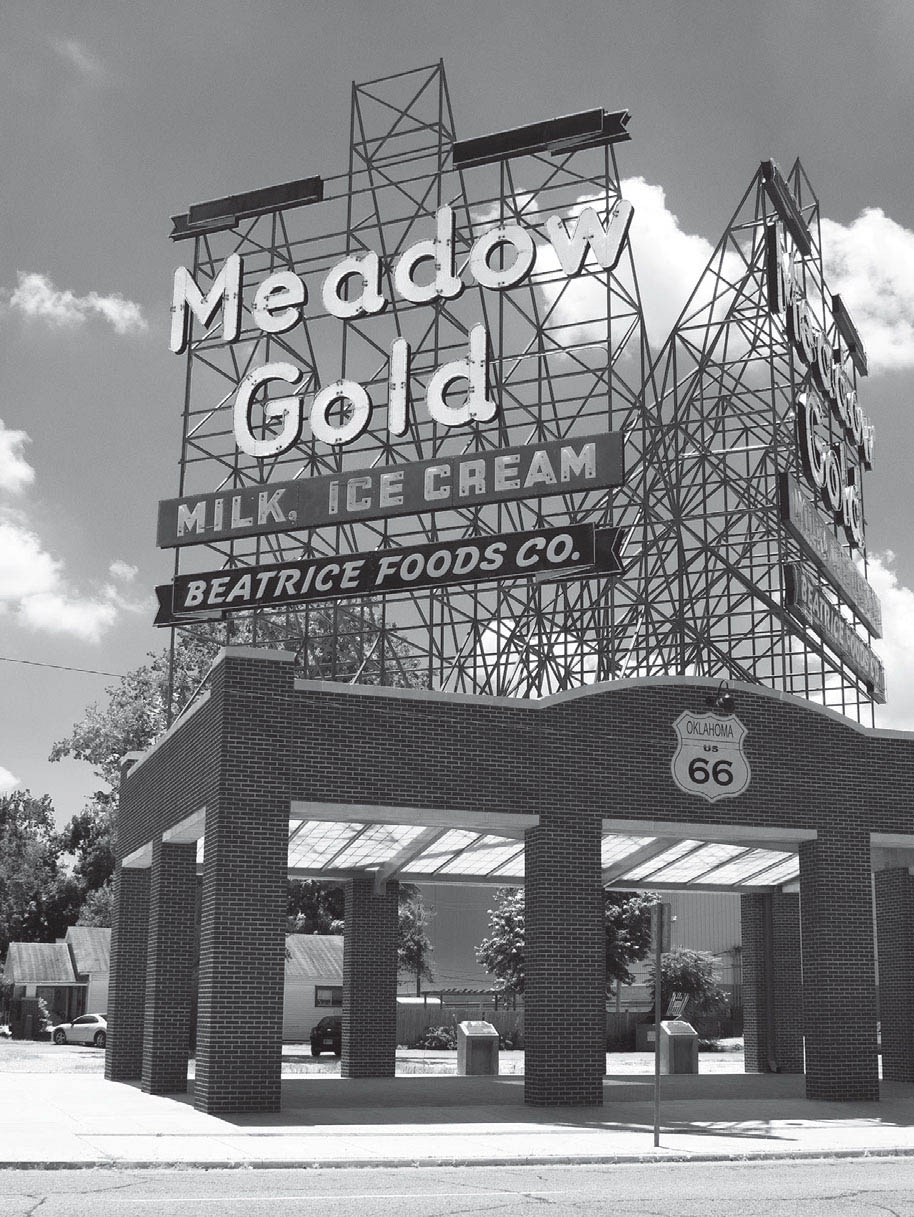

Also in the 1930s, Meadow Gold Dairy, at that time a part of Beatrice Foods, erected a large rooftop sign on a single-story building on Route 66. In 2004, with the building about to be demolished, the iconic Meadow Gold rooftop sign (E. 11th St. and S. Quaker Ave.) was saved and restored. It now sits proudly on top of a purpose-made brick base a few blocks to the west. The Meadow Gold neon was ceremonially re-lit in May 2009.

The restored and relocated Meadow Gold sign, Tulsa, Oklahoma. GPS: 36.14788,-95.97471

In June of 1921, Tulsa was the scene of a race riot which took the lives of more than thirty people and left the city’s African American district a burning ruin. Today, the Greenwood Cultural Center (322 N. Greenwood Ave.) and its Mabel B. Little Heritage House recall those dark days in the heart of Black Wall Street through photographs and memorabilia, while celebrating the neighborhood’s resiliency.

TULSA ATTRACTIONS

The Philbrook Museum (2727 S. Rockford Rd.) combines a historical home, extensive art collections, and twenty-three acres of beautiful gardens. The Italianate home was built in 1927 by oil man Waite Phillips, and has been featured on the program America’s Castles. Just a decade later, Phillips donated the estate to the city of Tulsa. Today, Philbrook is rated in the top sixty-five art museums in the country.

Tulsa, Oklahoma. GPS: 36.14788,-95.96821

The Gilcrease Museum (1400 N. Gilcrease Museum Rd.) houses one of the world’s most extensive collections of American Indian and Western art, and is surrounded by 475 acres of grounds with themed gardens.

East side of Tulsa, Oklahoma. GPS: 36.14813,-95.87259

The Willard Elsing Museum (7777 S. Lewis Ave.), on the campus of Oral Roberts University, features a four-foot jade sculpture among its sixty-year-old collection of gems, minerals, crystals, and other stones. Mr. Elsing at one time operated a rock and mineral shop on Route 66 at Joplin, Missouri. Enter at the giant Praying Hands sculpture, which is about sixty feet tall and weighs thirty tons—a rather arresting sight.

Lovers of Art Deco architecture have plenty to be thankful for here in Tulsa. A well-known example is the Boston Avenue Methodist Church (1301 S. Boston Ave.). Church tours are held every Sunday following the 11:00 AM service, or by appointment during the week. There are also a number of Art Deco office buildings in the downtown business district. You can take an Art Deco walking tour of the city by picking up a brochure at the Tulsa Chamber of Commerce (1 W. 3rd St.).

Blue Dome district, downtown Tulsa. GPS: 36.15581,-95.98694

There is a Frank Lloyd Wright creation (3700 S. Birmingham Ave.) in a residential section of Tulsa. It’s still a private residence, so no tours are available, but you can view two of its exterior facades by driving by.

Lovers of miniatures will want to see the Ida Dennie Willis Museum of Miniatures, Dolls, and Toys (628 N. Country Club Dr.). The collection includes an ever-changing array of trains, planes, robots, and dolls, all housed in a 1910 Tudor mansion. One of many interesting exhibits is the Gates collection of ethnic and advertising dolls.

The Tulsa Air and Space Museum & Planetarium (3624 N. 74th E. Ave.), which is on the grounds of the Tulsa International Airport, has lots of aircraft on display, including an F-14 Tomcat (same as the one used in Top Gun) and a Lear 24D corporate jet. For those addicted to hands-on experiences, flight simulators are also on hand.

The Tulsa Historical Society Museum (2445 S. Peoria Ave.), located in a 1919 mansion, is the official repository of the city’s history, including official documents, vintage photographs, and other artifacts.

A drive-in movie theater, the Admiral Twin Drive-In (7355 E. Easton St.), still operates in the northeastern sector of town. Starting out with a single screen in 1951 and called the Modern Aire, the name was changed a short time later when the second screen was added. The theater is featured as a hangout for characters in 1983’s feature film The Outsiders, directed by Francis Ford Coppola.

Tulsa is oil country. GPS: 36.13334,-95.93080

At Creek Council Oak Park (1750 S. Cheyenne Ave.), a 170-year-old oak tree marks the spot where the Creek Indians arrived in the 1830s after traversing the Trail of Tears, thus establishing the site which would later become Tulsey-town.

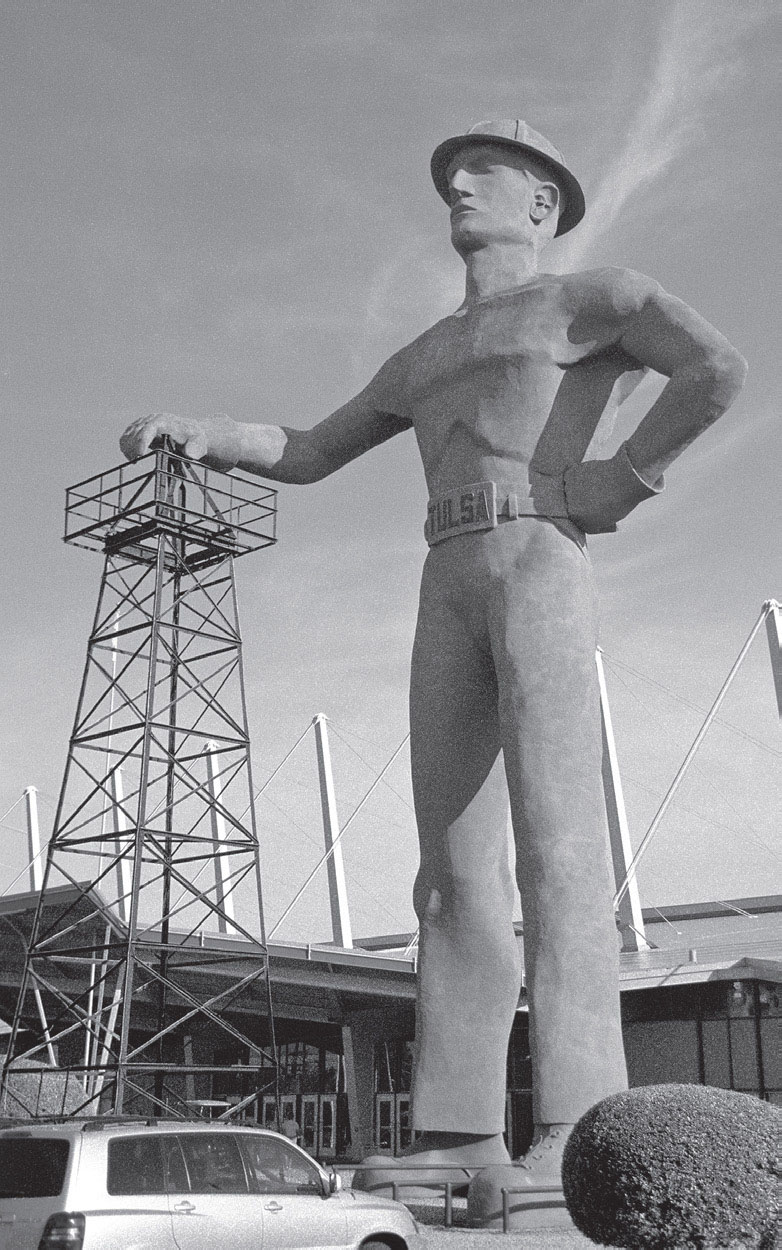

There’s a seventy-six-foot-tall oil worker sculpture, known as the Golden Driller, standing outside Tulsa Expo Center (4145 E. 21st St.). The center is said to contain the world’s largest unobstructed interior volume. The roof is suspended by a system of booms and cables, which allows adequate room inside for oversized equipment shows. In fact, the original Golden Driller (he was upgraded in the 1970s) was put on display inside the building for a while prior to his outdoor placement in 1966.

Tulsa, Oklahoma. GPS: 36.14452,-96.00306

In downtown Tulsa you’ll find the Center of the Universe (1 S. Boston Ave.), a sort of acoustical mystery location. Stand in this spot, recite some words, and you’ll hear your voice strongly reverberating back to you. The effect is quite striking. The location is marked by a circular design in the Boston Avenue pedestrian walkway.

Just yards away from the Center of the Universe is the Oklahoma Jazz Hall of Fame (5 S. Boston Ave.), which is housed in the Art Deco-inspired former Tulsa Union Railroad Depot, as well as a seventy-two-foot sculpture titled Artificial Cloud, created in the early 1990s for the city’s Mayfest celebration.

In downtown Tulsa, on a very early alignment of Route 66, stands the Blue Dome (S. Elgin Ave. and E. 2nd St.). A distinctively shaped former gasoline station, the restored Blue Dome is now the de facto centerpiece of a thriving new entertainment district.

FURTHER AFIELD

About forty-seven miles north of Tulsa is the city of Bartlesville. The city’s historic district includes nearly fifty buildings from the oil boom period of 1900 to 1920. Bartlesville is also home to the Inn at Price Tower (510 S. Dewey Ave.), a Frank Lloyd Wright creation from 1956 said to have been designed based on the structure of a tree. It’s now a hotel and museum with twenty-one architecturally fascinating guest rooms, some of which are two-story suites. The inn also has its own restaurant and bar.

The Bartlesville Community Center (300 SE Adams Blvd.) was designed by a student of Wright’s (Wesley Peters) and features the world’s largest cloisonné mural.

The Frank Phillips Home (1107 SE Cherokee Ave.) is a twenty-six-room Neoclassical mansion completed in 1909. Phillips was the founder of the Phillips Petroleum Company, the firm that branded their gasoline with a highway shield emblazoned with the number “66.” You can find out more about Phillips and and his business at the Phillips Petroleum Company Museum (410 S. Keeler Ave.).

Frank Phillips’s country home and guest ranch, which he named Woolaroc (1925 Woolaroc Ranch Rd.), is just outside Bartlesville. The ranch was designed as a sort of Old West preserve, and attracted the likes of presidents, tycoons, and other celebrities of the day as guests. The 3,700-acre compound, established in 1925, features a museum of Western art, a collection of Phillips Petroleum memorabilia, a lodge house, picnic areas, nature trails, a petting barn, roaming bison, and the Phillips family mausoleum.

The Bartlesville Area History Museum (401 S. Johnstone Ave.) is on the fifth floor of the City Center, formerly known as the Hotel Maire and later named the Burlingame. Of course, the museum has many things on exhibit, but at the core of it all is a collection of photographs taken by Frank Griggs, who moved to the area in 1908 and began recording daily life through about 200,000 photographic negatives.

Discovery 1 Park (200 N. Cherokee Ave.), formerly called Johnstone Park, contains a replica of the first commercial oil well in Oklahoma, named the Nellie Johnstone No. 1.

Bartlesville also holds an annual Bi-Plane Expo the first weekend of June.

Not far from Bartlesville is the town of Dewey, home to the Tom Mix Museum (721 N. Delaware St.). Before he became a movie star, Mix served as marshal in Dewey from 1911 to 1912. Three of his five wives were from this town. Mix’s film career came to include more than 300 films, some of which are available for viewing in the museum’s small auditorium.

The Dewey Hotel (801 N. Delaware St.) in downtown Dewey was built in 1900 and now serves as a museum.

A few miles east of Dewey on Durham Road is Prairie Song Indian Territory (402621 W. 1600 Rd.), a replica nineteenth-century village of twenty or so hand-hewn log buildings.

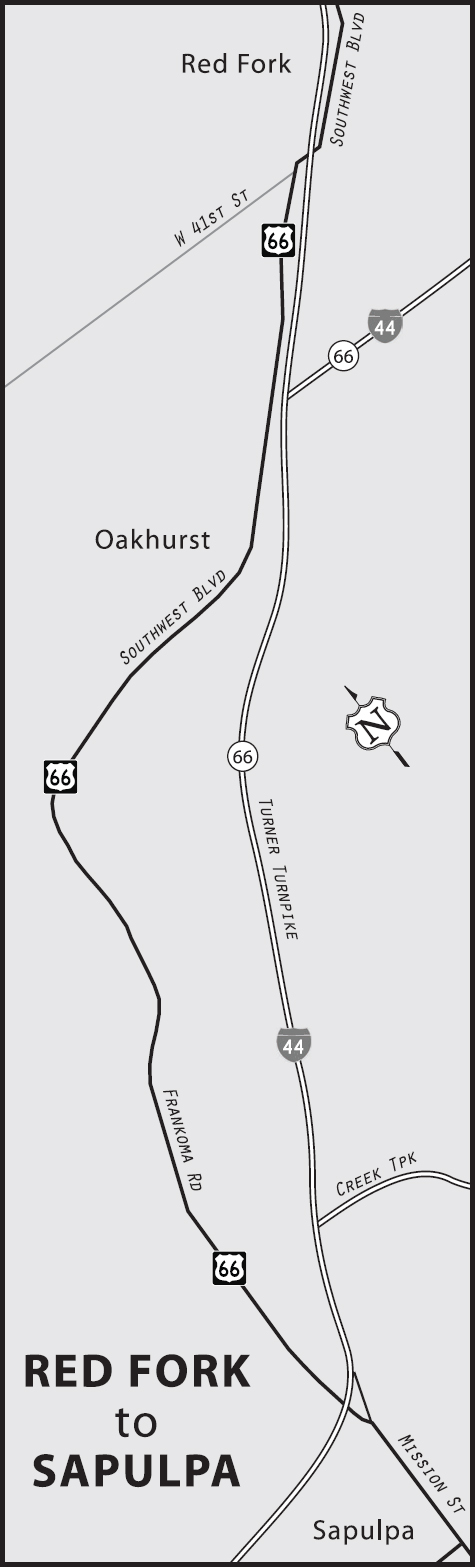

![]() Leave Tulsa on Southwest Boulevard. Follow Southwest, which becomes Frankoma Road, en route to Sapulpa via the communities of Red Fork and Oakhurst (see the reference map).

Leave Tulsa on Southwest Boulevard. Follow Southwest, which becomes Frankoma Road, en route to Sapulpa via the communities of Red Fork and Oakhurst (see the reference map).

RED FORK–OAKHURST

Recently added at Red Fork is the Route 66 Village (3770 Southwest Blvd.), consisting of some rail cars and an oil derrick.

Route 66 Village is a railroad-dominated roadside display in the Red Fork area (west Tulsa). GPS: 36.10798,-96.01614

SAPULPA

![]()

![]()

Entering Sapulpa, Old Sapulpa Road and New Sapulpa Road merge to form N. Mission Street. Route 66 then turns west on Dewey Avenue through the downtown district. West of downtown, keep alert for the old alignment that crosses Rock Creek on a brick-paved bridge.

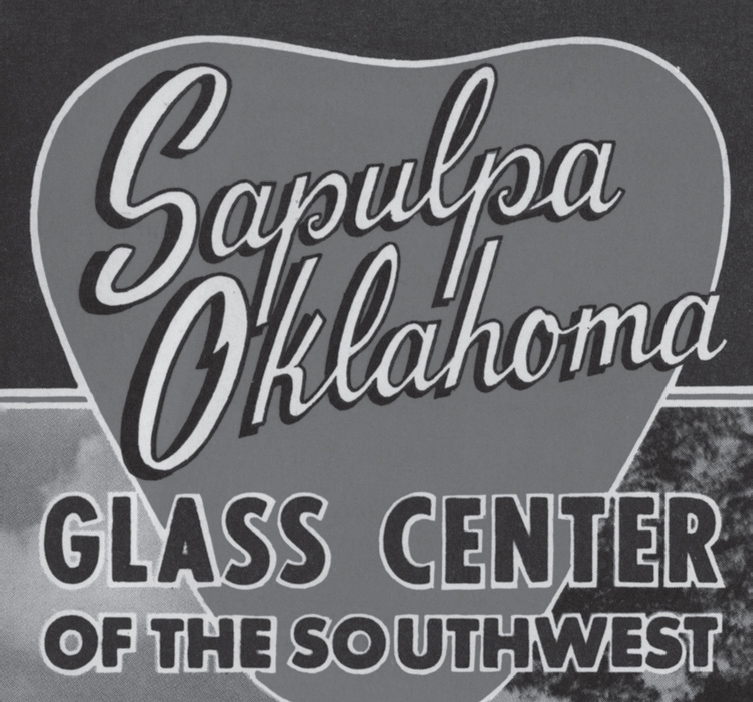

The former Liberty Glass Company (1000 N. Mission St.) was established here in the early 1900s by George F. Collins. The idea for the name seems to have come from the fact that 1886—the year Sapulpa was established—was the same year that France gave the gift of the Statue of Liberty to the United States. In A Guide Book to Highway 66, Jack Rittenhouse mentions Liberty Glass when describing his journey through Sapulpa in 1946.

Downtown Sapulpa includes a number of reproductions of antique advertising murals. These appear on the sides of several buildings along old Route 66.

Be sure to explore Sapulpa thoroughly, because an older alignment at the far end of town takes you over a brick-paved iron truss bridge called Rock Creek Bridge and past the Tepee Drive-In theater (13166 W. Ozark Trail). This alignment will take you back in time for a bit and well away from the roar of traffic.

On an old alignment of 66, Sapulpa, Oklahoma. GPS: 35.99471,-96.13969

SAPULPA ATTRACTIONS

Although the well-known Frankoma Pottery Company has closed, the Frank family home (1300 Luker Ln.) is now open for tours, conducted by John Frank’s daughters, Joniece and Donna. The home was designed in the mid-1950s by Bruce Goff, and incorporates brickwork and tiling in the traditional Frankoma Pottery styles and colors. Tours may be scheduled by calling (918) 224-6566.

Local boosterism brochure.

Housed in a circa-1910 building that was formerly the home of the YWCA, the Sapulpa Historical Museum (100 E. Lee Ave.) features an 1890s-era kitchen and schoolroom, a telephone exhibit, and items pertaining to the Frisco Railroad.

The Sapulpa Fire Museum (124 E. Lee Ave.) includes historic photos, vehicles, and other artifacts.

Now-extinct roadside stand near Kellyville, Oklahoma.

The Waite Phillips Filling Station Museum (26 E. Lee Ave.) is a beautifully restored 1923 structure that includes several period automobiles.

KELLYVILLE

On my earlier trips through here, there was an old store west of Kellyville with a plywood American Indian sign out front. The Indian’s arm was extended, as if pointing, and lettering on his outstretched arm promised: SOUVENIRS. Long closed, it was a treat for the Route 66 traveler to stumble upon. The sign has since been removed, however, and the remaining structures are nondescript. This is one of many disappearances reminding me to photograph, photograph, photograph.

![]() The road is easy to follow west of Kellyville, and you’ll cross over I-44 along the way and approach Bristow from the north (see the reference map).

The road is easy to follow west of Kellyville, and you’ll cross over I-44 along the way and approach Bristow from the north (see the reference map).

BRISTOW

According to the local chamber of commerce, Bristow’s 6th Avenue was at one time known as “Silk Stocking Row,” due to the fact that there were more millionaires living here than in any other place in Oklahoma.

BRISTOW ATTRACTIONS

The Bristow Historical Museum (1 Railroad Pl.) is located in a restored 1923 railroad depot and features rotating exhibits pertaining to the area’s history, from its time as Indian Territory to the present.

As you pass through Bristow, keep your eye out for a sign pointing to the Wake Island Memorial (Veteran’s Memorial Dr.) in the western part of town. The city has commemorated those veterans who served in the Battle of Wake Island in the Second World War, and there are some nice pedestrian-friendly walking paths in the vicinity.

![]() You can’t see it, but along the stretch of road between Bristow and Stroud, there is an enormous underground storage cavity—a depleted gas field—which is used to store natural gas during periods of surplus. What you can see is that there are at least three cemeteries along Route 66 between Bristow and Depew, and then there are two more west of Depew, where 66 approaches the Turner Turnpike (I-44).

You can’t see it, but along the stretch of road between Bristow and Stroud, there is an enormous underground storage cavity—a depleted gas field—which is used to store natural gas during periods of surplus. What you can see is that there are at least three cemeteries along Route 66 between Bristow and Depew, and then there are two more west of Depew, where 66 approaches the Turner Turnpike (I-44).

Downtown Depew, Oklahoma. GPS: 35.80296,-96.50752

DEPEW

The village of Depew is rather isolated. The Mother Road cut off the somewhat circuitous route through Depew early on. Take at least a few extra minutes to drive through this town, though. You’ll see evidence that it was once a much busier place.

Bristow, Oklahoma. GPS: 35.83581,-96.38823

OZARK TRAIL MARKERS

The Ozark Trail marker near Stroud is one of several which once stood in the area. There is a similar one—a replica—in the town of Stratford, Oklahoma, erected in the summer of 1997. That reproduction includes an inscription that is instructive for today’s explorer:

OZARK TRAIL PYRAMID

By 1916, plans were underway to promote a network of roads through Oklahoma called the “Ozark Trail.” The trails were planned by the Ozark Trail Association. Its mission was to promote a system of better roads connecting the surrounding states. These were the first roads to be classed as public supported highways.

Early plans were “grandiose.” Originally the Ozark Trail was to be a link from ocean to ocean. The route was to be marked with impressive pyramids and concrete mileage posts. These roads were intended to be “above high water, hardsurfaced, and later oiled.” Routes increased rapidly as towns competed to be included on the Trail.

The Ozark Trail Pyramid was one of many marking the trail for travelers in the early 1920s. Oklahoma trails crossed the state, east to west and north to south. They have either become U.S. Highways or follow the same course, such as U.S. 60, U.S. 62, OK 9, the famous “Route 66,” and the current Turner Turnpike. This pyramid was one of several placed on the trail from Tulsa to Dallas. Chandler, Meeker, Shawnee, and Sulphur also had identical pyramids marking the trail along this particular route.

Work began on the Stratford Pyramid in December 1921. The buried base was six feet square, the next section was four feet square, the top tapered and stood twenty-two feet high. The original pyramid stood in the center of Main and Hyden Streets, which is only ½ block to the east. Due to traffic and safety reasons, this replica pyramid could not be in the original location. It was constructed as close to the original site as possible. “Ozark Trail” appeared on all four sides of the upper part of the pyramid and each side listed the mileage for the next towns along the route. In April 1923, the pyramid was wired and lighted. In the early 1940s, it was pushed over and buried where it stood. In the early 1970s, its pieces were exhumed, partially restored, and now stands on a private ranch near Stratford. One other “original” pyramid, which is presumed to be the Chandler pyramid, is located west of Stroud off Highway 66.

This replica was erected in the summer of 1997.

STROUD

Stroud was established in 1892. Henry “Bear-Cat” Starr and his gang robbed two banks here in 1915. Starr was the nephew of the famed Belle Starr.

A stop at the Rock Café is a longstanding Route 66 tradition. Stroud, Oklahoma. GPS: 35.74891,-96.65428

The focal point of Stroud is the Rock Café (114 W. Main St.), which is built of stones that were unearthed during the construction of Route 66 in the area. The café features a nice sign that fans of neon will appreciate. The Rock Café suffered a devastating fire in May 2008, and there were a lot of doubters who thought it was lost to us. However, through a lot of hard work and the sheer determination of the café’s owner, Dawn Welch, “The Rock” reopened one year later, nearly to the day. Dawn, by the way, also happens to be a big part of the inspiration behind the character of Sally the Porsche in the 2006 movie Cars.

Also in Stroud is the Skyliner Motel (717 W. Main St.), which also has a good-looking neon sign. Look for it near the west end of town.

STROUD ATTRACTIONS

The Stroud Library (301 W. 7th St.) is an example of 1929 Art Deco architecture, and was originally built by Bell Telephone.

Stroud, Oklahoma. GPS: 35.74918,-96.66220

This part of Oklahoma considers itself wine country, and there are indeed several wineries nearby if that’s your thing. As an example, just a mile or so west of downtown Stroud is StableRidge Vineyards and Winery (2016 OK-66). Their tasting room is in a former Catholic Church that was built from 1898 to 1902.

Stroud is home to the International Brick & Rolling Pin Competition and Festival. The competition pits a handful of cities named Stroud against one another in games of skill. The other Strouds are in Canada, Australia, and the U.K.

West of Stroud, there is a left turn you can take (at N. 3540 Rd.) that follows the old Ozark Trail Highway. This early 66 alignment features an Ozark Trail monument (a tall obelisk) at one of its intersections. This old path of the highway is more easily spotted when facing east, because the later Route 66 alignment curves to your left, and straight ahead is an obviously older alignment that will take you directly to the marker—that’s the way I was first able to find it.

DAVENPORT

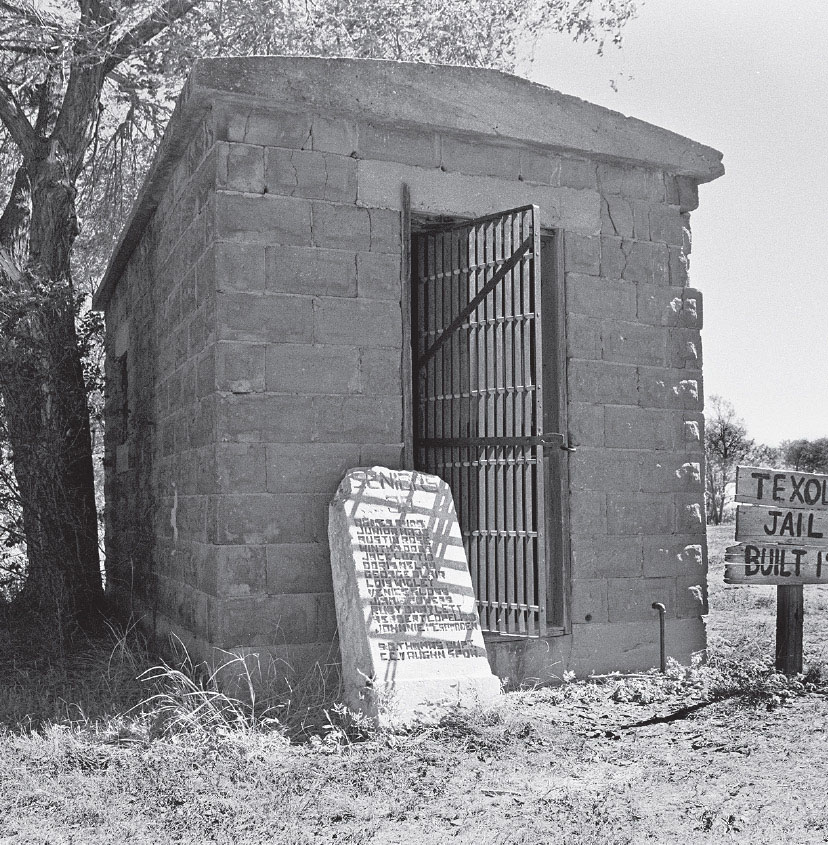

Watch for high water in this vicinity. The first time I took Route 66 through Oklahoma, I had to skip Davenport altogether due to the closure of several roads at the time. There is an old Texaco station (Broadway Ave. and 7th St.) in town that has an ever-changing array of vintage vehicles parked on its lot. Painted on the side of one of the buildings in the tiny downtown district is artwork known as the Land Run Mural (Broadway Ave. and Main St.).

Downtown Davenport, Oklahoma. GPS: 35.70531,-96.76531

Davenport, Oklahoma. GPS: 35.71058,-96.76574

![]() Be on the lookout for the Lincoln Motel (740 E. 1st St.) as you reach the eastern outskirts of Chandler. Built in 1939, and very much a product of the 66 era, the motel is still in business. Our friend Rittenhouse made mention of it way back in 1946.

Be on the lookout for the Lincoln Motel (740 E. 1st St.) as you reach the eastern outskirts of Chandler. Built in 1939, and very much a product of the 66 era, the motel is still in business. Our friend Rittenhouse made mention of it way back in 1946.

CHANDLER

Chandler, the seat of Lincoln County, was established with a land run in 1891, and calls itself the Pecan Capital of the World. The town of Cromwell, southeast of here in Seminole County, is reputed to be the site of the last Old West-style gunfight. That was in 1924, and it took the life of Bill Tilghman, former U.S. marshal at Dodge City and sheriff of Lincoln County, Oklahoma. Poor Bill—he was seventy years old and had been retired for quite a few years when he was called upon that one last time. Tilghman is buried in the Oak Park Cemetery on the west side of Chandler.

The former National Guard Armory is now a Route 66 must-stop in Chandler, Oklahoma. GPS: 35.70967,-96.87630

CHANDLER ATTRACTIONS

The Route 66 Interpretive Center (400 E. Rte. 66) opened in 2007 in what was once the National Guard Armory. It’s located right where 66 takes a sweeping left turn, transitioning from east–west 1st Street to north–south Manvel Avenue. Aside from the Mother Road exhibits, the building also houses offices for the Oklahoma Route 66 Association and the local chamber of commerce.

While in Chandler, consider paying a visit to Jerry McClanahan’s art gallery, McJerry’s Route 66 Gallery (306 Manvel Ave.), in the north part of town. Jerry’s Route 66 artwork is well-known, and he was honored with the prestigious Will Rogers Award in June 2010. Hours are irregular (after all, he’s an artist), so be sure to call ahead: (903) 467-6384.

The heart of Chandler, Oklahoma. GPS: 35.70371,-96.88090

Further to the south on Manvel Avenue is an old cottage-style Phillips 66 station. It has gradually been receiving restorative work. For example, it had been modified from its original form by the addition of two garage bays, probably during the 1950s, but those additions have now been removed.

Chandler, Oklahoma. GPS: 35.69547,-96.88080

The Lincoln County Museum of Pioneer History (717 Manvel Ave.) showcases Chandler’s colorful early history, with an emphasis on their legendary sheriff, Bill Tilghman. It also hosts Miss Faye’s Touring Historical Marionette Theater and rare films by cinematographer Benny Kent.

![]() Between Chandler and Warwick there is a Meramec Caverns barn. However, you won’t notice it heading west, as the painted side of it faces eastbound travelers in hopes of enticing them to stop at the cave many miles ahead of them in Missouri.

Between Chandler and Warwick there is a Meramec Caverns barn. However, you won’t notice it heading west, as the painted side of it faces eastbound travelers in hopes of enticing them to stop at the cave many miles ahead of them in Missouri.

Motorcycle Museum, Warwick, Oklahoma. GPS: 35.68637,-97.00004

Near Warwick, Oklahoma. GPS: 35.69556,-96.94547

WARWICK

In the loosely defined community of Warwick, you’ll come upon the Seaba Station Motorcycle Museum (336992 OK-66). This museum has been restored by its newest owners to its circa-1920s state, and their passion for motorcycles is on full display. The building was formerly an engine-rebuilding shop and gasoline station. Take a look in back for the stone outhouse, still standing after so many years.

WELLSTON–LUTHER

Wellston was cut off from the main route in the 1930s, but there is a loop through town that is marked as 66B that follows the older, more circuitous alignment. At the junction of 66B on the east side of town is the site once occupied by Pioneer Camp, a tourist campground; a pair of masonry bases that once supported an archway over the entrance to the camp are still visible here. You’ll also find the Butcher Barbeque Stand (3402 W. Rte. 66) here.

Business district of Luther, Oklahoma. GPS: 35.66179,-97.19589

This old station is slowly decaying between Luther and Arcadia, Oklahoma. GPS: 35.66012,-97.27373

Luther has a small downtown just south of the highway with several vacant storefronts.

West of Luther, you can access a dead-end remnant of an older 66 alignment. There is a large sign at the entrance marked “Private Historical Site.”

Further west of Luther and just east of Arcadia are the remains of a stone gasoline station (circa 1920s) reputed to have been the scene of a counterfeit ring. It’s small, but it’s also one of my favorite ruins on the route, one that I photograph each and every time I pass through here. With each visit, I find that these ruins have deteriorated a bit more.

ARCADIA

There is a historical marker on the eastern outskirts of town designating the eastern boundary of the infamous 1889 Land Run.

ARCADIA ATTRACTIONS

Arcadia has a literary connection. Washington Irving, well-known as the author of the popular tale “Rip Van Winkle,” camped here in 1832. He wrote about his travels in this area in A Tour of the Prairies, which was published in 1835. Look for the marker east of the Round Barn (107 Oklahoma 66). Mr. Irving is considered by some to be the United States’ earliest professional author, having written A History of New York in 1809 under the pseudonym Diedrich Knickerbocker. Like Shakespeare, Irving is credited with putting some phrases of his own invention into the vernacular. He is credited with the expression “almighty dollar,” referring to “that great object of universal devotion throughout our land.” He also is credited with the expression “happy hunting ground” to refer to the American Indians’ life in the hereafter. If that’s not enough, then consider that his pen name of Knickerbocker has been synonymous with New York and New Yorkers since shortly after the publication of his A History of New York at the tender age of twenty-six.

The Round Barn has stood in Arcadia, Oklahoma, for well over 100 years. GPS: 35.66216,-97.32583

The Round Barn, a world-famous Route 66 landmark, was constructed in 1898. The barn, which was restored in the 1990s and now houses a small gift shop, is filled with photographs and other memorabilia having to do with unusual barns around the world. These include circular and octagonal barns, as well as other unconventional configurations. The upper level, above the gift shop, is available for rental for special events.

Also on the National Register is the Tuton Drug Store (201 N. Main St.), which is now the office of Chesrow-Brown Real Estate.

Keep your sleuthing eyes open in Arcadia for a very old alignment of Route 66 that deviates from the main pavement for a short distance, and includes the home of author and publisher Jim Ross (13100 E. Old Hwy 66). Ross took his inspiration for the house’s design from the ever-popular cottage-style Phillips 66 stations.

One of the newer roadside attractions on the route is this sixty-six-foot-tall lighted pop bottle. Arcadia, Oklahoma. GPS: 35.65879,-97.33554

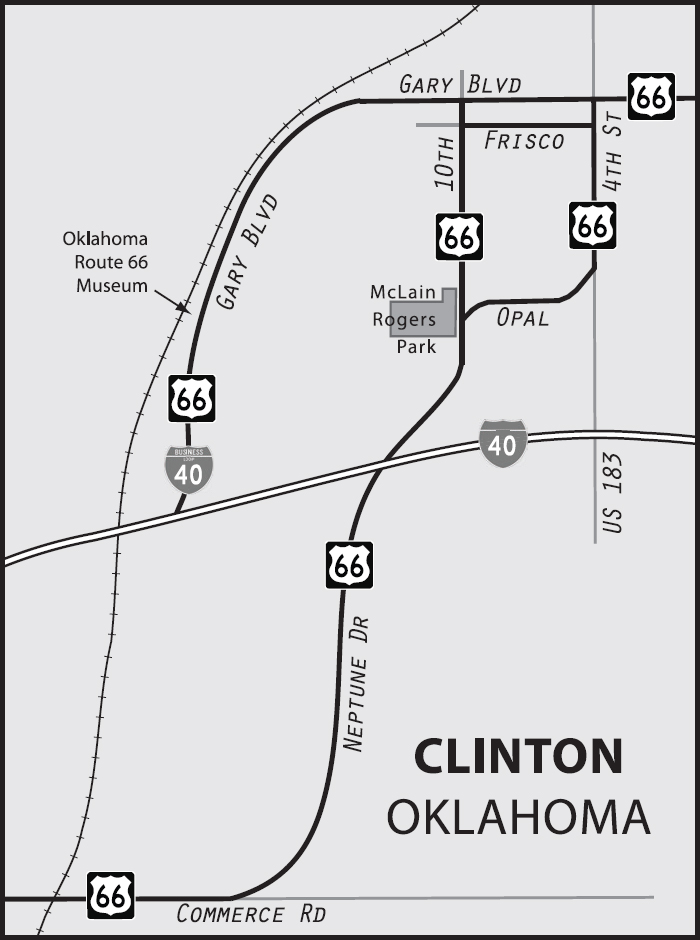

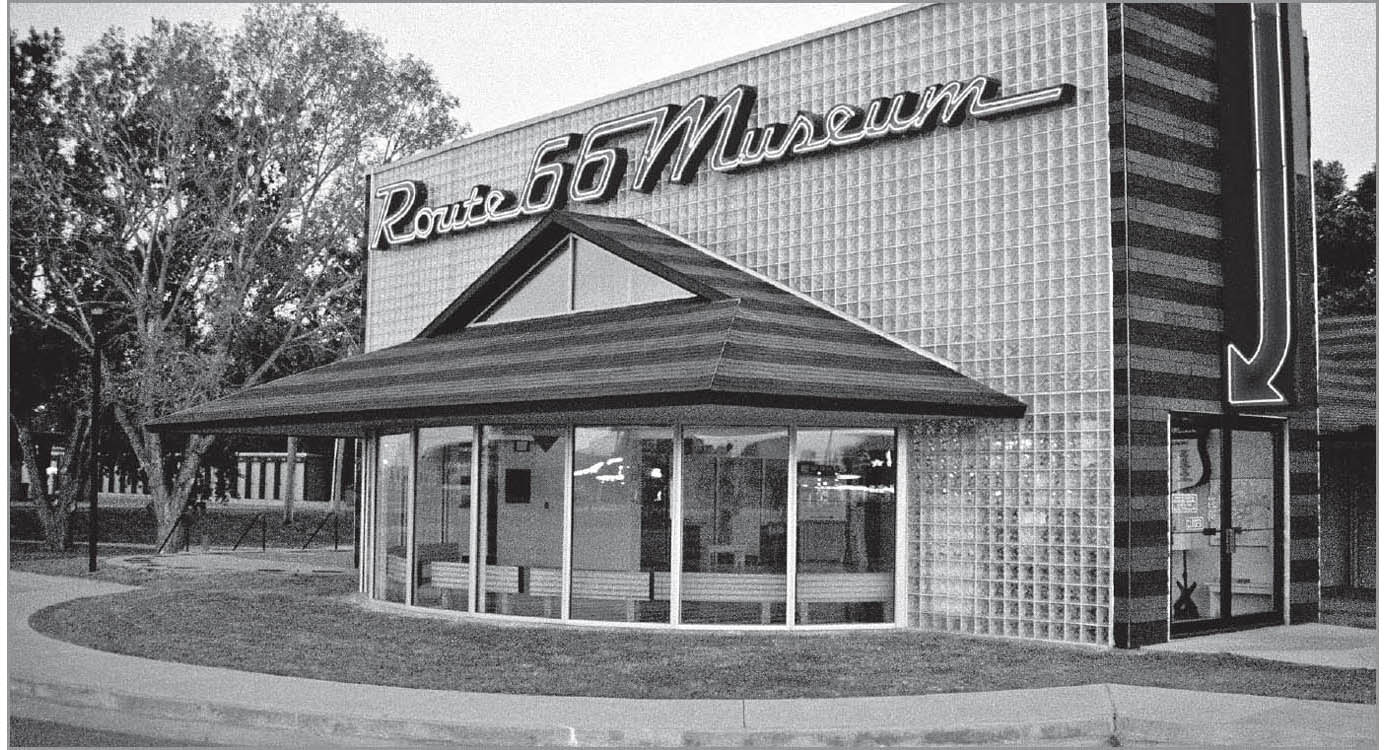

The western outskirts of Arcadia are dominated by the monumental POPS (660 Oklahoma 66), a new Route 66 attraction that reaches out and grabs your attention like classic tourist traps of the past. You certainly can’t miss a sixty-six-foot-tall illuminated pop bottle standing a few yards from the roadway. Inside, POPS has countless brands and flavors of soft drinks to choose from, as well as a snack bar and internal combustion fuel for your iron horse. This decidedly over-the-top concept was brought to life by Rand Elliott, the same architect who designed the Oklahoma Route 66 Museum in Clinton, Oklahoma, in the 1990s.

ELMER McCURDY

For those of you interested in strange stories, this has to be one of the strangest. I have read four or five slightly different accounts of the Elmer McCurdy saga, and each one is as bizarre as the next.

In 1976, a film crew shooting an episode of The Six Million Dollar Man was on location at a Los Angeles-area fun house. One of the crew members moved what was thought to be a dummy hanging from the ceiling, but the “dummy’s” arm fell off. Inside were what appeared to be the bones and joints of a real human being. That man was soon identified as Elmer McCurdy.

McCurdy was an outlaw who died in a shoot-out at the hands of authorities in 1911. His body was taken to a mortuary in Pawhuska, Oklahoma, where the undertaker, not knowing how long he might need to hang on to the body before it was claimed, added arsenic to the usual embalming fluid and thereby mummified McCurdy’s remains. Months passed, and the body still had not been claimed. By this time, McCurdy’s corpse had become something of a local attraction, and people came by and paid a nickel apiece to look at it.

Many years later, the funeral home had changed hands, the principals in the whole affair were deceased, and no one knew any more that the dried-up “dummy” in town was a real human body. A carnival passed through and offered to take the “dummy” off the current owner’s hands for a small price. A deal was struck, and Elmer McCurdy entered show business posthumously.

No one knows for sure just how many places McCurdy’s mummified body had been displayed before he was discovered at the fun house that day in 1976. No relatives ever presented themselves to claim the body. Finally, a historical group arranged for McCurdy’s body to be returned to Oklahoma for burial. The Warren Monument company of Guthrie furnished a tombstone bearing the inscription:

ELMER MCCURDY

SHOT BY SHERIFF’S POSSE IN OSAGE HILLS ON OCT 7, 1911 RETURNED TO GUTHRIE, OKLAHOMA FROM LOS ANGELES COUNTY, CALIFORNIA FOR BURIAL, APR 22, 1977

McCurdy was then laid to rest in Summit View Cemetery in Guthrie, Oklahoma. To ensure that the body would remain interred and not be trotted out again as a curiosity, the state medical examiner ordered that two cubic yards of concrete be poured over the coffin before the grave was closed.

FURTHER AFIELD

A real treat awaits you just a short trip north of old 66. Just a few miles east of downtown Edmond, take either 12th Street or U.S. 77 north for twenty miles or so to the very historic town of Guthrie, Oklahoma. On the outskirts of the town, you’ll see a still-working drive-in theater. In business since 1951, the Beacon Drive-In (2404 S. Division St.) had an appearance in the movie Twister.

For some twenty years, beginning in 1890, Guthrie was the capital of Oklahoma (or Indian Territory, as it was known at the time). Virtually all of the city’s downtown was constructed during that period, and today, Guthrie boasts the largest contiguous urban historical district on the National Register, consisting of 2,169 structures in 400 blocks on 1,400 acres, including fourteen city blocks of Victoriana. The territory achieved statehood in 1907, and the capital was moved to Oklahoma City a few years later in 1910. The National Trust for Historic Preservation honored Guthrie as one of its “Dozen Distinctive Destinations” in 2004.

Tom Mix used to tend bar here at the still-hopping Blue Belle Saloon (224 W. Harrison Ave.). Just outside the Blue Belle, staged gunfights are held in the street for much of the year.

The Scottish Rite Temple (900 E. Oklahoma Ave.) is among the largest of its kind in the world, with an enormous number of stained-glass artworks. Guided tours are available.

The Gaffney Building (214 W. Oklahoma Ave.) houses both the Chamber of Commerce and the Oklahoma Frontier Drug Store Museum. The folks at the C of C will answer any questions you may have, and the drug store is well worth touring. Not only will you see all the tools of the trade from a circa-1890 pharmacy, but the attendant on duty when we were there was extremely knowledgeable, having been a practicing druggist himself for many years. In 2006, an apothecary garden was added to cultivate and study medicinal plants.

Physically connected to one of the 1,946 public libraries endowed by the Carnegie Foundation in this country, the Oklahoma Territorial Museum (406 E. Oklahoma Ave.) presents a history of Oklahoma during its earliest days, including the Land Run of 1889 and the subsequent influx of settlers. There is even some information about the infamous case of Elmer McCurdy.

![]() Back on Route 66 heading west out of Arcadia, past POPS, there is little Route 66 flavor evident between here and the town of Edmond; however, the stretch is rather rural in character and therefore relaxing.

Back on Route 66 heading west out of Arcadia, past POPS, there is little Route 66 flavor evident between here and the town of Edmond; however, the stretch is rather rural in character and therefore relaxing.

EDMOND

Following Route 66 through Edmond means turning left (south) at Broadway. A right at that corner takes you into the smallish business district.

This schoolhouse dates from pre-statehood days. Edmond, Oklahoma. GPS: 35.65288,-97.47884

EDMOND ATTRACTIONS

In Edmond you’ll find the 1889 Territorial School (124 E. 2nd St.), the first public school established in Oklahoma Territory. It later housed a camera shop beginning in 1950, but in 2007 it was rededicated in keeping with its historical past.

The Edmond Historical Society Museum (431 South Blvd.), housed in an armory building constructed by the WPA in 1936, displays photos, documents, and artifacts relating to the town’s development. There are also traveling exhibits, which change throughout the year. In the 1950s, this building was used to house and train dancing bears for the local circus.

The Arcadian Inn (328 E. 1st St.), a bed and breakfast, was originally a one-story private residence built in 1908. Twenty years later, the owner decided to convert it to two stories by lifting up the original house and constructing a new first story and basement underneath. How’s that for doing things the hard way?

Edmond is proud to be a supporter of public art. Stone and bronze sculptures, as well as a number of murals, can be seen throughout the city. A guide published by the city’s convention and visitors bureau lists 115 works of art, including a WPA-era etched glass mural inside the city hall (101 E. 1st St.).

If you like unusual architecture, you can check out the Hopewell Baptist Church (5801 NW 178th St.), designed by Bruce Goff in the 1940s. It’s been nicknamed the TeePee Church, since that’s what it was built to resemble. It is conical in shape, about eighty feet tall, and was constructed using “tent poles,” which are actually surplus oilfield pipes donated by an oil drilling company.

![]() Between Edmond and Oklahoma City is Memorial Park Cemetery (13313 N. Kelley Ave.). This is the burial place of Wiley Post. Although Post is more widely known these days as the friend of Will Rogers who was piloting the plane in which they both perished in 1935, he was actually very accomplished in his own right. He first attained prominence in 1930 by winning the National Air Race Derby, a race from Los Angeles to Chicago (ring a bell?) in a plane named the Winnie Mae. He made the first successful solo flight around the world in 1933, and also designed the first pressurized flight suit. The aviator’s likeness and biography are carved in a large stone over the burial plot.

Between Edmond and Oklahoma City is Memorial Park Cemetery (13313 N. Kelley Ave.). This is the burial place of Wiley Post. Although Post is more widely known these days as the friend of Will Rogers who was piloting the plane in which they both perished in 1935, he was actually very accomplished in his own right. He first attained prominence in 1930 by winning the National Air Race Derby, a race from Los Angeles to Chicago (ring a bell?) in a plane named the Winnie Mae. He made the first successful solo flight around the world in 1933, and also designed the first pressurized flight suit. The aviator’s likeness and biography are carved in a large stone over the burial plot.

![]()

![]()

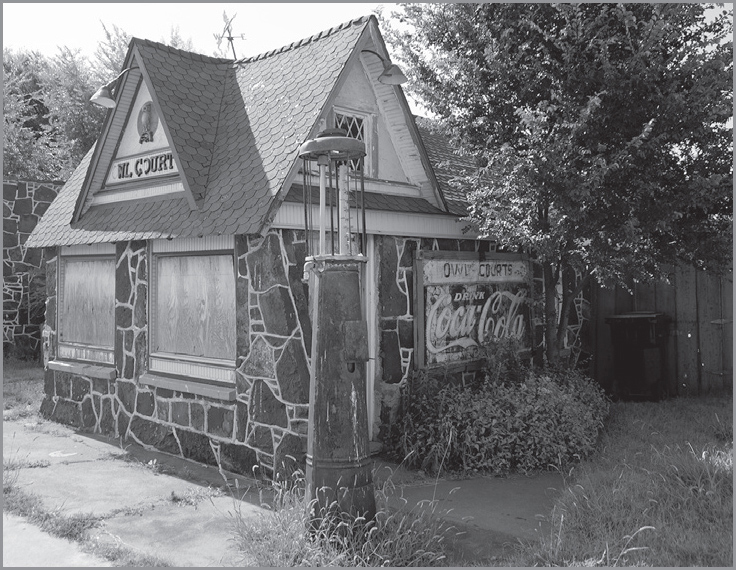

Between Edmond and Oklahoma City, leave U.S. 77/Broadway at Kelley Avenue and continue south. From there, you have a couple of choices, including a “beltway” route that skirted downtown but took in the village of Britton, where the Owl Courts tourist complex still stands. The primary route went all the way to the capitol before turning west.

The Owl Courts in much better days.

OKLAHOMA CITY

Oklahoma City successfully ousted Guthrie as the state capital in 1910. For many years, the capitol building (2300 N. Lincoln Blvd.) here was unusual for this country, because it didn’t have a dome. A dome was indeed a part of the original design, but it was omitted for reasons of economy. In 2002, the citizens of Oklahoma decided to finally top their capitol with a dome, so the one you see today is a modern add-on. Oil was struck here in 1928, and before the boom was over, there were twenty-four oil wells pumping on the actual grounds of the Oklahoma state capitol.

The Owl Courts complex is on the bypass portion of Route 66 in the community of Britton. Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. GPS: 35.56548,-97.52711

Route 66 took many different paths through Oklahoma City over the years, so you would do well to explore extensively if you can tolerate the traffic. The best-known route traced present-day Broadway out of Edmond (which becomes Kelley) straight toward the capitol, where it turned west on 23rd, north on May, and west again on NW 39th Street Expressway. Alternatively, a turn from Kelley onto Britton Avenue and then a left on Western Avenue takes you through the village of Britton along a more obscure “beltline” route. Also, be sure to cruise Classen Avenue, where you’ll see a great example of symbolic architecture when you pass a little triangular building with a giant milk bottle on top.

Here’s what the state capitol looked like until the dome was finally added in the twenty-first century.

This old postcard depicts a dome that was designed, but not actually built.

The first automatic parking meter was invented and installed in Oklahoma City by brothers Carlton and Gerald Hale on July 16, 1935. Initially, the meters were placed on only one side of the downtown street. Within three days, the merchants from the other side of the street petitioned to have their side metered also. They liked the constant and rapid turnover that the meters engendered. Two years later, on June 4, 1937, Sylman Goldman introduced the first shopping cart here.

On July 22, 1933, Machine Gun Kelly kidnapped millionaire Charles Urscher from his home (327 NW 18th St.). Kelly was the gangster who coined the phrase “G-Man.”

OKLAHOMA CITY ATTRACTIONS

Oklahoma City has known tragedy. The worst-ever act of terrorism on American soil—up until that time—occurred here April 19, 1995, at the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building. Be sure to visit the Oklahoma City National Memorial (620 N. Harvey Ave.).

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. GPS: 35.49411,-97.53212

In the heart of Oklahoma City is the Myriad Botanical Gardens and Crystal Bridge Tropical Conservatory (301 W. Reno Ave.). Truly an oasis, the gardens cover a seventeen-acre tract and include rolling hills surrounding a sunken lake. The focal point of the gardens is the seven-story, 224-foot-long Crystal Bridge Tropical Conservatory, a greenhouse providing a habitat for an extensive collection of palms, orchids, cacti, and exotics from around the world.

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. GPS: 35.49318,-97.53469

Be sure to pay a visit to the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum (1700 NE 63rd St.)—formerly the National Cowboy Hall of Fame. This is a large, first-rate complex that includes major exhibition galleries, a replica turn-of-the-century Western town, and several heroic-sized works of sculpture, including a rendering of James Earle Fraser’s world-famous End of the Trail, which won a gold medal at the 1915 Pan-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. Fraser also designed the Indian Head (or Buffalo) nickel, which began production in 1913. Also contained within the museum is the Hall of Fame of Western Film, which includes video clips and other memorabilia associated with the likes of Gene Autry, Gary Cooper, Tom Mix, and Slim Pickens, among many others. There is also a research archive that includes photographs, papers, and the personal effects of actor Walter Brennan and several other Western notables.

Route 66/Western Avenue, Oklahoma City. GPS: 35.56255,-97.53102

Just down the street from this museum is Gabriella’s Italian Grill (1226 NE 63rd St.). In the 1930s, this place was a speakeasy known as the Kentucky Club, and was frequented by Pretty Boy Floyd. The building reportedly has features such as trap doors to facilitate escape in the event of a police raid.

The Science Museum Oklahoma (2100 NE 52nd St.) is actually a collection of museums. Included are the Hands-On Science Museum, the Kirkpatrick Planetarium, and the Air Space Museum. With all of these attractions essentially under one roof, it’s a near-overdose for the mind.

Built in 1958, the Gold Dome (1112 NW 23rd St.) was constructed using R. Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic dome principles, and includes a gold-anodized aluminum roof. The Dome originally housed a bank, but has recently been rehabilitated for retail and office space.

The Paseo Arts District, centered at NW 30th and Dewey, is a historically rich neighborhood that has been taken over by the city’s art community. Several artists have studios and galleries in this area, and the district hosts an annual art festival each Memorial Day weekend.

Bricktown is a former warehouse district that has been turned into an entertainment hot spot with bars, restaurants, and music clubs. Recently added are some canals, which are plied by water taxis. The loading area for the narrated taxi rides is across from the Chickasaw Bricktown Ballpark (2 S. Mickey Mantle Dr.), home of the minor-league Oklahoma City Dodgers. The American Banjo Museum (9 E. Sheridan Ave.), which claims to have the largest collection of banjos in the world, relocated to Bricktown in 2009 after having been in the town of Guthrie for years.

The Oklahoma Country & Western Music Hall of Fame (3925 SE 29th St.) consists of more than 10,000 square feet of items dedicated to country-and-western music performers.

The 45th Infantry Division Museum (2145 NE 36th St.) is a highly regarded military museum and has something of interest for everyone. Oklahoma’s role in the Civil War and American Indian Wars is represented here, but displays also include items from Hitler’s bunker that were captured by the 45th in 1945. There are over 200 original “Willie and Joe” cartoons by artist Bill Mauldin, and outside are dozens of military vehicles, aircraft, and artillery.

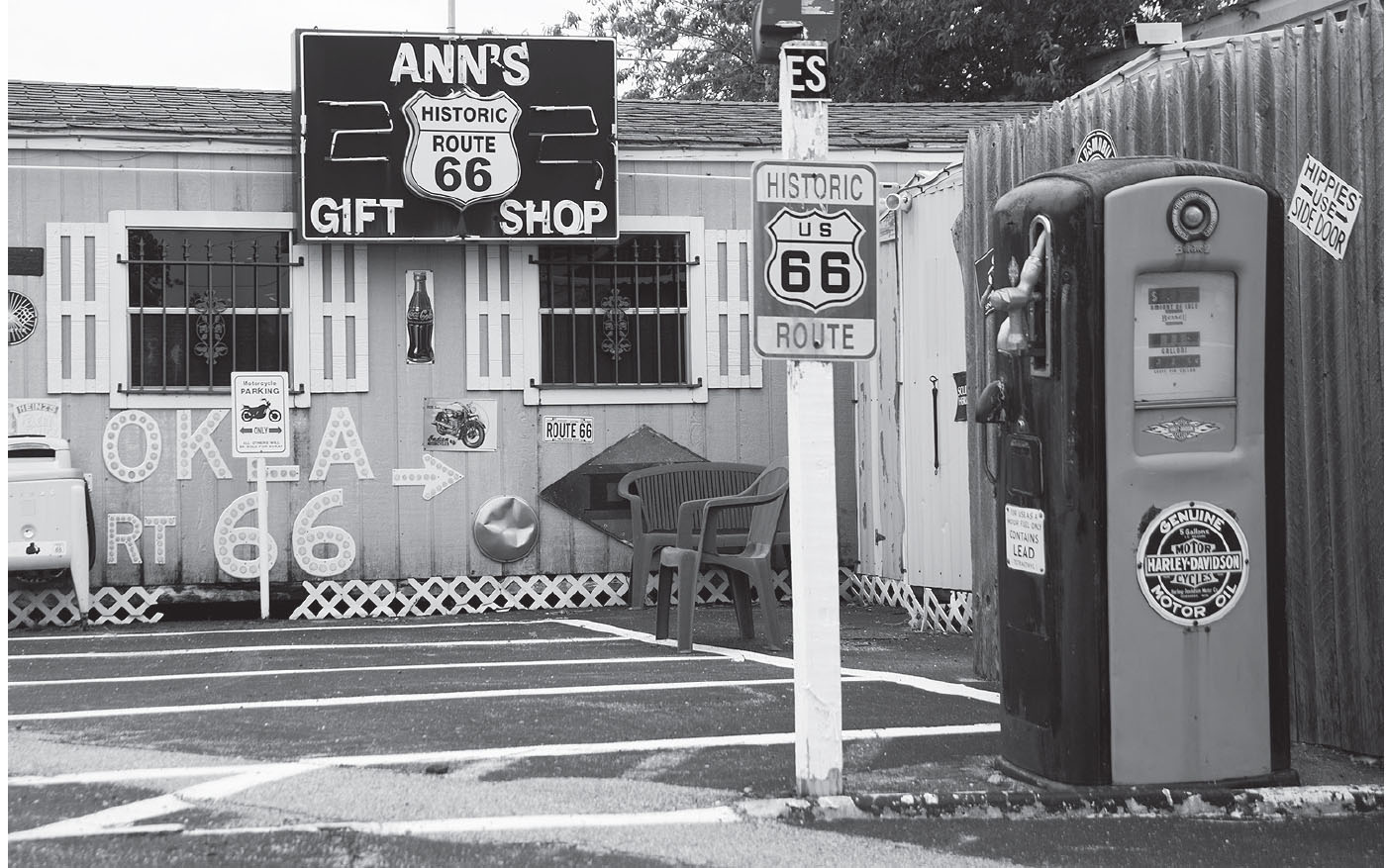

Evidence of the Mother Road spirit in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. GPS: 35.51117,-97.59312

At Ann’s Chicken, Oklahoma City. GPS: 35.51117,-97.59312

On the grounds of the Will Rogers World Airport is the 99s Museum of Women Pilots (4300 Amelia Earhart Ln.). Amelia Earhart is prominently represented here—as well as other early female aviators—and there are materials on display pertaining to women in the space program.

The Oklahoma State Firefighters Museum (2716 NE 50th St.) has helmets on display worn by Ben Franklin, John Hancock, and Paul Revere. Also on display is Oklahoma’s first fire station (established in 1864) as well as 100-year-old fire equipment that was actually used in Oklahoma communities.

The National Softball Hall of Fame and Museum (2801 NE 50th St.) covers all variants of the game, including fast, slow, and modified-pitch versions. The museum is housed in the Amateur Softball Association (ASA) headquarters. The ASA stadium hosts national and world class competitions in the sport.

The Jim Thorpe Association and Oklahoma Sports Hall of Fame (4040 N. Lincoln Blvd.) honors excellence in athletics, with a variety of awards and scholarships that they bestow annually.

The Henry Overholser Mansion (405 NW 15th St.) was built, naturally, by Henry Overholser. This 1903 Victorian-style home contains ninety percent of the original family furnishings and is notable for its hand-painted, canvas-covered walls.

Built in 1928, the Governor’s Mansion (820 NE 23rd St.) offers guided tours every Wednesday. The house is said to be haunted by the ghost of Oklahoma’s Depression-era governor, William H. “Alfalfa Bill” Murray. On the grounds is a swimming pool shaped like the state’s boundaries.

The Oklahoma History Center (800 Nazih Zuhdi Dr.) has over 200,000 square feet devoted to the state’s heritage, organized by themes such as aviation, commerce, and geology, to name just a few.

The Harn Homestead & 1889er Museum (1721 N. Lincoln Blvd.) is a complex of structures not far from the state capitol building. This homestead was claimed in the Land Run of 1889, and includes a stone-and-cedar barn, three houses, and the former Stoney Point School, a one-room schoolhouse dating from 1897. The school was in regular use until 1947, and was moved here in 1988.

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. GPS: 35.51493,-97.52986

Does pigeon racing tickle your fancy? The American Pigeon Museum and Library (2300 NE 63rd St.) has dedicated itself to the heritage of the pigeon. A project of the American Homing Pigeon Institute, there is a small museum housed in a 1930s brick house on ten acres of land. There are educational exhibits, pigeon lofts, and cultivated gardens. Pigeon races are held in the fall. White pigeons are also available here for release at weddings and other special events.

The World Organization of China Painters Museum (2700 N. Portland) houses a large collection of hand-painted China, along with a gift shop, research library, and classrooms.

The Classen High School Museum (1901 N. Ellison St.) and the Central High School Museum (815 N. Robinson St.) are in competition to see who has the best school spirit. Classen has the country’s largest high school alumni organization and boasts Admiral William Crowe as one of its constituents. Central High’s building (circa 1910) was designed by the architect of the state capitol and is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Evolved from an organization called the Oklahoma Hall of Fame, the Gaylord-Pickens Oklahoma Heritage Museum (1400 Classen Dr.) opened its high-tech doors in 2007, and has received several accolades. The museum seeks to tell the story of Oklahoma through its most distinguished citizens, and you can search the database of more than 600 hall of fame inductees going all the way back to 1928.

The Oklahoma Museum of Telephone History (111 Dean A. McGee Ave.) covers more than a century’s worth of history in the form of vintage telephones and telephone company memorabilia.

The Oklahoma Railway Museum (3400 NE Grand Blvd.) is an open-air museum with a family-friendly vibe. You can even ride a train!

Oklahoma City still has an operating drive-in movie theater, the Winchester Drive-In (6930 S. Western Ave.), built in 1968. It’s located on the south side of town, away from the Mother Road.

![]() You’ll leave Oklahoma City headed west on 39th Street Expressway.

You’ll leave Oklahoma City headed west on 39th Street Expressway.

WARR ACRES–BETHANY

Warr Acres was named for a real estate developer named Clyde B. Warr. The town of Bethany was established in 1906 by members of the Nazarene Church. Today, both cities seem to be embedded in Greater Oklahoma City. The Bethany Historical Society Museum (6700 NW 36th St.) is located inside city hall.

Route 66 is a multilane, divided thoroughfare in these parts. Just west of Bethany, it crosses a corner of Lake Overholser. Named for OKC mayor Ed Overholser, the lake at the time of Rittenhouse was a recreational area with speedboat rides. Prior to World War II, plans were laid to make Lake Overholser a layover center for seaplane excursions. This, of course, is a mode of travel that never really caught on well. Today, Alaskans use seaplanes very commonly, but they are short on roads up there.

This old bridge is at the edge of Lake Overholser, west of Bethany, Oklahoma. GPS: 35.51463,-97.66275

![]() A few years ago, I would have strongly encouraged you to take the old 66 alignment that crosses the vintage (1924) Lake Overholser Bridge and then hugs the lake’s northern shoreline (N. Overholser Drive). It meets up with the later Route 66 alignment at Yukon. However, that stretch of road has undergone such build-up and modernization lately that there’s little of the Route 66 flavor left, so there isn’t much to recommend it anymore. Don’t feel bad if you skip it by staying on the later alignment.

A few years ago, I would have strongly encouraged you to take the old 66 alignment that crosses the vintage (1924) Lake Overholser Bridge and then hugs the lake’s northern shoreline (N. Overholser Drive). It meets up with the later Route 66 alignment at Yukon. However, that stretch of road has undergone such build-up and modernization lately that there’s little of the Route 66 flavor left, so there isn’t much to recommend it anymore. Don’t feel bad if you skip it by staying on the later alignment.

YUKON

Singer Garth Brooks and actor Dale Robertson both hail from Yukon, and there is a sign at the edge of town proudly proclaiming Brooks as its native son. Pay a visit to the Garth Brooks Water Tower (I-40 and Garth Brooks Blvd.).

YUKON ATTRACTIONS

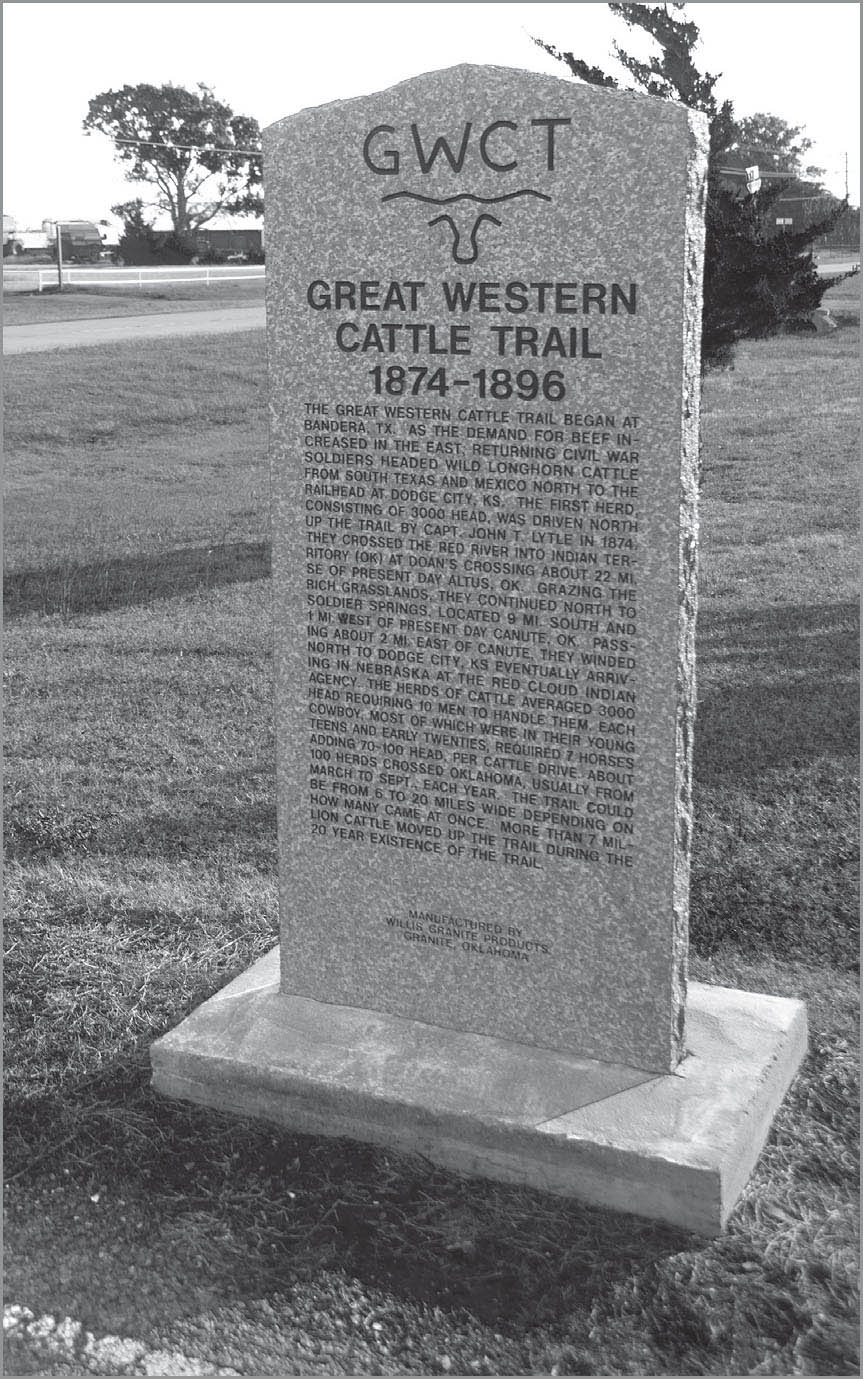

You are in Chisholm Trail country now. Some sources say that 9th Street through Yukon closely approximates the route of the Chisholm Trail. Other sources say that U.S. 81, which runs through El Reno farther west, is more authentic. In truth, being a cattle trail, the Chisholm was of course never paved, so the precise route varied considerably. It was subject to the vagaries of such things as water availability, prevailing weather, and individual whim. What we can be more certain of is that the trail ran from southern Texas, through central Oklahoma, and on to the cattle markets in Abilene, Kansas. The trail was named for Jesse Chisholm, who was among the first to make regular use of the trail and to advocate its use by others. Yukon holds a Chisholm Trail Festival every year, as do many of the towns and cities through which the trail once passed.

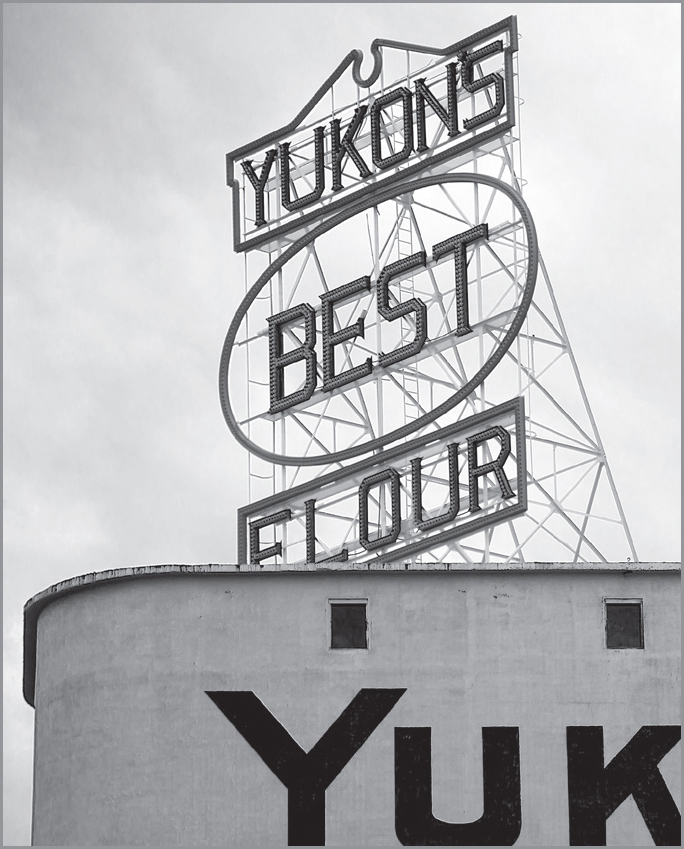

Yukon, Oklahoma’s biggest landmark. GPS: 35.50784,-97.74666

The Yukon Community Center (2200 S. Holly Ave.) has a Chisholm Trail monument and also contains a “Bank Shot” setup. This is a sort of cross between basketball and miniature golf, consisting of bizarrely shaped backboards on which you can test your skill and patience in sinking your “free throws.” I’ve never seen one of them anywhere else.

A major landmark here in Yukon is the Yukon’s Best Flour mural, which is emblazoned prominently on the side of a grain storage facility on the south side of the highway in town, right at the railroad tracks.

Yukon’s Best Railroad Museum (328–346 Cedar Ave.) is a static display of a caboose and other rail cars across the boulevard from the Yukon’s Best Flour mural. Full tours of the rail cars can be scheduled by calling (405) 354-5079.

The Yukon Historical Society Museum (601 Oak St.) is housed in a 1910 school building and includes a doctor’s office, Czech history room, and other local history.

About five miles north of town is Express Clydesdales (12701 W. Wilshire Blvd.). Rare black-and-white Clydesdale horses make their home here in a 1936 barn restored by Amish specialists from Indiana. There is also a gift shop and visitor center.

EL RENO

El Reno sits at the junction of two famous highways of very different kinds: U.S. 66 and the Chisholm Trail (roughly at U.S. 81). The town, which is the seat of Canadian County, was reportedly named for a Civil War general, Jesse L. Reno, who was killed in action in 1862.