Is It Possible to Become a Permanently Happier Person?

An Overview of the Issues and the Book

Kennon M. Sheldon1 and Richard E. Lucas2, 1University of Missouri–Columbia, Columbia, MO, USA, 2Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA

Subjective well-being—a construct that is known more colloquially as “happiness”—is a characteristic that reflects a person’s subjective evaluation of his or her life as a whole. Although the construct is based on a person’s own perspective, it is thought to reflect something about the actual conditions of people’s lives. These conditions include both external conditions such as income and social relationships, as well as internal conditions such as goals, outlook on life, and other psychological resources. Moreover, people who evaluate their lives negatively would likely be motivated to improve the conditions of their lives, and those who evaluate their lives positively would be motivated to maintain or further improve these conditions. Thus, happiness and related constructs are thought to signal how well a person’s life is going, which should mean that as a person’s life improves, so should the happiness that that person reports.

Keywords

subjective well-being; happiness; external condition; internal condition; Self-Determination Theory

Subjective well-being—a construct that is known more colloquially as “happiness”—is a characteristic that reflects a person’s subjective evaluation of his or her life as a whole. Although the construct is based on a person’s own perspective, it is thought to reflect something about the actual conditions of people’s lives. These conditions include both external conditions such as income and social relationships, as well as internal conditions such as goals, outlook on life, and other psychological resources. Moreover, people who evaluate their lives negatively would likely be motivated to improve the conditions of their lives, and those who evaluate their lives positively would be motivated to maintain or further improve these conditions. Thus, happiness and related constructs are thought to signal how well a person’s life is going, which should mean that as a person’s life improves, so should the happiness that that person reports.

Over the years, however, at least some researchers became quite skeptical about the possibility for change in happiness. Initial reviews of the literature suggested that few external, objectively measured life circumstances were strongly related to subjective well-being (Diener, 1984; Diener, Suh, Lucas, & Smith, 1999; Wilson, 1967). In addition, some highly cited studies suggested that even individuals who had experienced extremely strong positive and negative life events (such as winning the lottery or becoming disabled) barely differed in their self-reported happiness (e.g., Brickman, Coates, & Janoff-Bulman, 1978; but see Lucas, 2007, for a reinterpretation of this finding). This evidence, when considered in the context of increasing numbers of studies showing strong heritability for reports of happiness and relatively high stability over time, led some to suggest that change was not possible (e.g., Brickman & Campbell, 1971; Lykken & Tellegen, 1996; see also Diener, Lucas, & Scollon, 2006, for a review).

If these perspectives are true, then they present major problems for the field of positive psychology (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). Positive psychology is the scientific study of positive human states, traits, and other characteristics, and positive psychology is premised on the notion that these desirable qualities can all be improved through the application of scientific research (at the population level) and personal effort (at the individual level). Since the very beginning of positive psychology, happiness has been one of the most important topics of study—in part because happiness is so important to most people (hence the thousands of happiness books marketed to laypeople), and in part because the right to “pursue happiness” is a right guaranteed to all U.S. citizens (and citizens of Western democracies more generally). If it turns out that greater happiness cannot be successfully pursued, then it calls into question whether higher levels of other positive personality characteristics (i.e., virtues, strengths, capabilities) are also impossible to achieve. Perhaps positive psychology is ultimately based on an illusion, and perhaps people should learn to be content with who they are and what they have, rather than continually trying to put “legs on a snake,” as it were (Gaskins, 1999).

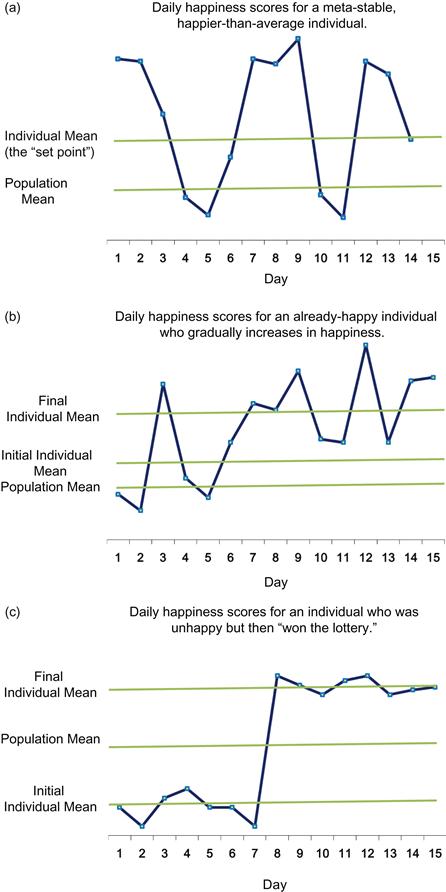

Although there has been increasing research on the question of “sustainable happiness” (i.e., the possibility of achieving a higher level of happiness that is sustainable above one’s initial level) in the past decade, there is still little scientific consensus on whether happiness can go up and then stay up (as opposed to falling back to baseline). Some illustrations of the possibilities are given in Figure 1.1 (panels 1a–1c). Notably, Figure 1.1 references only positive deviations from initial baselines, but it could just as easily reference negative deviations. However, such “sustainable drops” in well-being are not considered in this book, except by Cummins, in Chapter 5.

Panel 1a illustrates a case in which all well-being increases are only temporary, representing mere fluctuations around a constant baseline. Because of autoregressive effects, the person always tends to return to his or her own stable, underlying baseline. This is the assumption of genetic set point theories and theories which propose complete adaptation to all changes. Panel 1b illustrates a case in which the baseline trends upward over time. For a variety of possible reasons, including learning, maturation, or steadily improving life circumstances, well-being is continually improving for this person, although there remain bumps in the road. Panel 1c illustrates a second way that well-being might go up and stay up. The panel illustrates a step function in which the baseline is elevated all at once and remains stable at the new level (the dream of those who buy lottery tickets!). Together, the three panels also illustrate that individual baselines can be located relative to a population baseline, so that we may talk about individual change with respect to population baselines as well as with respect to the person’s own prior levels of well-being. One implication of the autoregressive perspective is that stable patterns of positive change should be rare, the further the person’s initial baseline is from the population baseline. An already very happy person should have more difficulty gaining and maintaining new happiness than a person who is only of average happiness initially. In contrast, a person who starts out below the population mean might have an easier time increasing in happiness, to at least a state of moderate contentment.

The goal of this book is to bring together leading scholars with a broad range of perspectives to discuss the question of whether happiness can change. The book is structured in such a way as to highlight three specific sets of issues regarding the extent to which happiness can change. First, in the early parts of the book, we highlight theoretical approaches to understanding change in happiness. In other words, if happiness can or cannot change, it is important to consider why that might be and what theoretical explanations can account for this phenomenon.

For instance, one possibility is that although happiness can change in the short term, long-term levels may be determined primarily by in-born genetic predispositions. In 1996, David Lykken and Auke Tellegen published an article called “Happiness is a stochastic phenomenon,” which argued that people’s happiness levels are fixed, at least over the long term, by genetic factors that are not changeable. Although people of course fluctuate in the short term in their happiness levels (i.e., they have moods), they will always tend to return to their particular baseline well-being level in the end, “regressing to their own mean,” as it were. This mean is commonly referred to as the “happiness set point.” In concluding their argument, based on twin study data, Lykken and Tellegen (1996) stated that “trying to become happier is like trying to become taller”—in other words, it will not work.

Although Lykken later backed away somewhat from this position (Lykken, 1999), it remains a widely accepted perspective on the question of whether happiness can change. In this book, Røysamb, Nes, and Vittersø, re-examine this issue, focusing specifically on the theoretical implications of behavioral genetic research on subjective well-being. After providing a very lucid discussion of behavioral genetic approaches, along with a review of behavioral genetic research, they then discuss what the moderate heritability estimates really mean for research on subjective well-being and for individuals who wish to improve their lives. Their discussion points out that the simple tendency to equate “heritable” with “unchangeable” is probably not justified.

Another theoretical reason for pessimism concerning the happiness change question is the phenomenon of hedonic adaptation. Hedonic adaptation, akin to sensory adaptation (Helson, 1964), refers to the tendency to cease noticing particular stimuli over time so that the stimuli no longer have the emotional effects they once had. For instance, we might assume that people who win large sums of money in the lottery will at first be ecstatic but may later adapt as wealth becomes their “new normal.” However, hedonic adaptation may also apply to many other life changes besides monetary ones, such as a new car, a new spouse, or a new child. What once provided a thrill becomes a mere part of the background. This phenomenon gives rise to what has been referred to as the “hedonic treadmill” (Brickman & Campbell, 1971); in this view, pursuing happiness is like walking up an escalator going down, so that one’s position can never really change. Notably, hedonic adaptation is not necessarily a bad thing: presumably the process is important for helping us to recover from negative events, with the downside that permanent increases due to positive events are unlikely.

Hedonic adaptation theories have become popular partly because of the way they correspond to other well-established processes of adaptation within the human body, including the sensory adaptation processes described previously. However, a close examination of sensory adaptation processes reveals that there are strict limits to the adaptation that can occur. A “room-temperature” building may at first feel quite warm to a person who came in from outside on a very cold day, or it might feel quite cool to someone who came in from outside on a hot summer day. Both people would be expected to adapt to this new temperature, and the room-temperature environment would cease to be noticeable. However, there is actually a very small range of indoor temperatures that people find comfortable and to which they will quickly adapt. Outside this small range, people’s experience is lastingly affected. Hedonic adaptation may function in a similar way. People may adapt quickly and easily to new circumstances as they happen, just as we adapt when we come in from the cold to a “room-temperature” location. However, just as few people intentionally keep their homes at a brisk 45 degrees during waking hours (i.e., they never adapt to temperatures this cold), people may never adapt to more extreme circumstances (Lucas, 2007).

An important goal for the section on theoretical perspectives is to put evidence for and against adaptation effects into theoretical context. Armenta, Bao, Lyubomirsky, and Sheldon discuss these issues from the context of intervention studies designed to improve well-being. In their program of research, they address theoretical reasons why some attempts at change may succeed, and they review evidence from intervention studies that address these possibilities. Similarly, DeHaan and Ryan discuss predictions from Self-Determination Theory in regard to the possibility for increased happiness, noting that this is more likely to result from eudaimonic than from hedonic life changes, especially changes that enhance one’s overall level of psychological need-satisfaction. In contrast, Cummins discusses the reasons we might expect gains in well-being, or at least certain forms of well-being, to always revert back to baseline levels after a period of adaptation. Cummins also discusses how, in the worst case, baseline levels might become established at a permanent, lower level. Together, the divergent perspectives that these chapters offer should stimulate new competing empirical tests regarding the potential for stable change.

Although the first section of the book addresses theoretical perspectives on the possibility for change (of course, with reference to relevant data regarding these points), the second section focuses more squarely on the empirical evidence that change does or does not occur (regardless of whether those data are especially relevant for a particular theory). Importantly, given the breadth of evidence related to this issue, many of the chapters focus on distinct types of evidence or specific empirical approaches to understanding whether happiness can change. For instance, Headey, Muffels, and Wagner identify a sizeable minority of participants in large panel studies that do report substantial changes in happiness over long periods of time and then identify the factors that may be responsible for that change. They focus on specific life choices that individuals make that may be responsible for these changes. Yap, Anusic, and Lucas also use data from large-scale panel studies, but they focus on identifying how much change occurs and which life events seem to be associated with change. Powdthavee and Stutzer address similar questions with an emphasis on how economists have approached the question of change and the analysis of data that might inform our understanding of these changes.

Other chapters focus on change in subjective well-being in specific contexts. For instance, Ruini and Fava discuss the extent to which happiness can change within the context of therapy, whereas Veenhoven and also Easterlin and Switek discuss whether there are societal factors that lead to long-term changes in national levels of happiness. Although this has been and still is a contentious issue within the literature on subjective well-being, these latter two chapters provide important evidence about the extent to which change does occur at this macro level and whether such changes may be related to government policies.

Finally, the third section discusses some remaining issues in the study of change in subjective well-being. For instance, Eid and Kutscher provide an important overview of methodological and analytical approaches to understanding stability and change, which will be an essential resource for researchers who wish to investigate the many issues raised in the earlier substantive chapters. In addition, Hill, Mroczek, and Young point out that there may be individual differences in the extent to which change can and does occur. Research that takes these individual differences into account may be better able to identify factors that are responsible for stability and change.

The question of whether happiness can change may be the most important question that subjective well-being researchers can tackle. If people’s long-term levels of subjective well-being are truly impervious to the effects of changing life circumstances, then attempts at intervention will be doomed to failure, well-being measures will provide little information to guide policy changes, and people’s perception that they are pursuing goals to maximize happiness will surely be wrong. Research into the stability of longitudinal well-being remains an area of considerable ambiguity and controversy, and the basic question of whether happiness can change has still not been definitively answered. We hope that by bringing together diverse scholars who approach this question from a wide variety of perspectives, this book will provide an overview of what is known so far and can guide future research on this critical topic.