Is Lasting Change Possible? Lessons from the Hedonic Adaptation Prevention Model

Christina Armenta1, Katherine Jacobs Bao1, Sonja Lyubomirsky1 and Kennon M. Sheldon2, 1University of California, Riverside, Riverside, CA, USA, 2University of Missouri-Columbia, Columbia, MO, USA

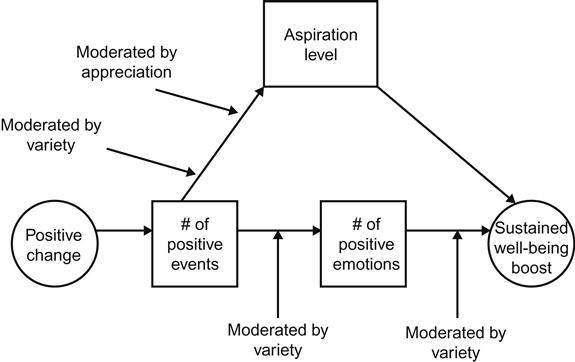

Happiness seekers tend to focus on changing their life circumstances, such as buying a new house, switching jobs, or getting married. However, people have been found to adapt to both positive and negative life changes, such as marriage, job promotion, disability, and widowhood. This process—known as hedonic adaptation—can serve as a formidable barrier to achieving lasting happiness. The Hedonic Adaptation Prevention model outlines why people adapt to life changes and sheds light on how adaptation to favorable events can be forestalled and how adaptation to unfavorable events can be hastened. In this chapter, we focus on a positive change as the model’s starting point, which is associated with an immediate boost in well-being and a gradual decline back to baseline. Individuals adapt to positive life changes due to increasing aspirations and declines in the number of positive events and emotions associated with the change. Fortunately, lasting happiness change is indeed possible, as adaptation can be slowed or arrested in a number of ways, such as feeling greater appreciation for the good things in life and introducing greater variety.

Keywords

hedonic adaptation; Hedonic Adaptation Prevention model; life changes; well-being; sustainable happiness

Happiness is highly valued both in Western society and in cultures all around the world (Diener, 2000). Many individuals spend their lifetimes searching for ways to achieve happiness and are confronted with a dizzying array of information to achieve their goal—from self-help books and motivational seminars to commercial advertising promoting cars, drinks, and technology as sources of well-being. Unfortunately, both anecdotal and scientific evidence yields mixed evidence with respect to the question of whether it is even possible to change one’s level of happiness. A principal reason for pessimism is that people possess a surprising ability to become accustomed to positive life changes—via a process called hedonic adaptation—possibly because they have genetically influenced happiness set points to which they return even after major ups and downs (Lyubomirsky, Sheldon, & Schkade, 2005). In this chapter, we discuss the implications of hedonic adaptation for sustainable happiness, and the ways that one might achieve lasting happiness change by thwarting adaptation.

Hedonic Adaptation

What Is Hedonic Adaptation?

Hedonic adaptation is the process by which people “get used to” events or stimuli that elicit emotional responses. After the experience of a positive or negative stimulus or event, one generally experiences a gain or loss in well-being (Frederick & Loewenstein, 1999). For example, a newlywed may experience a boost in well-being due to the positive events and emotions associated with the new marriage. These events might include moving into a new house together, throwing dinner parties as a couple, or even the simple act of being able to call one’s new spouse “husband” or “wife.” However, this change in well-being is ultimately followed by a gradual return to baseline. As the newlyweds become accustomed to the changes in their lives associated with marriage, the happiness they initially experienced begins to decline and eventually returns to baseline.

Hedonic adaptation occurs to both positive and negative events, and some amount of adaptation—even in the positive domain—may be beneficial. Frederick and Loewenstein (1999) have argued that hedonic adaptation is evolutionarily adaptive. When individuals experience high levels of positive or negative affect, they cannot help but focus on those intense feelings. This acute attention on their affect can make it difficult to function, because people need to concentrate on their basic needs in order to survive and thrive. Thus, people hedonically adapt as a means of reducing high arousal, allowing them to redirect their attention to more important needs, as well as to novel opportunities and threats. Also, high arousal may be physiologically harmful if experienced chronically, so reducing it may help people avoid physical ailments such as stress-related illness.

What Is Not Hedonic Adaptation?

Hedonic adaptation is similar to, yet distinct from, several other related processes. Because hedonic adaptation involves becoming accustomed to a stimulus, it is often confused with a similar concept, desensitization. Both hedonic adaptation and desensitization reduce the emotional intensity of an event. However, hedonic adaptation diminishes that intensity by shifting the perceptions of the positivity or negativity of a stimulus, such that what was initially observed as positive or negative becomes neutral (Frederick & Loewenstein, 1999). Consequently, people become more sensitive to differences in a stimulus. For example, a person moving into a 400-square-foot apartment may not initially observe much of a difference between his apartment and the 450-square-foot apartment next door. However, after he adapts to his current apartment, the apartment next door begins to appear much larger and more favorable in comparison. He may even become motivated to try to switch apartments. Desensitization, by contrast, reduces the affective intensity of an event more generally. It is characterized by reduced sensitivity toward differences in a stimulus. People who are desensitized would not notice the difference between their current 400-square-foot apartment and the 450-square-foot apartment next door, nor would they be motivated to attempt to substitute their apartment for the larger one. Thus, although desensitization and hedonic adaptation share certain characteristics, hedonic adaptation cannot be explained as merely desensitization to a stimulus.

The literature on hedonic adaptation involves several methodological issues. One concern is whether people truly adapt to life changes, or if the evident decline in well-being is a result of scale norming (Frederick & Loewenstein, 1999). Researchers generally measure happiness by asking participants to indicate their overall level of happiness on a scale from low to high (e.g., 1 to 7). Given the subjectivity of this approach, people may interpret the scale differently. For example, one person may interpret a 7 as being the absolute highest level of happiness a person could possibly achieve, whereas another may interpret a 7 as manifesting a high level of happiness in comparison to the average person. One alternative explanation for why people who have undergone a major life change (e.g., amputation) are not as unhappy as we might expect is that they might normalize the scale. In other words, they might subconsciously rate themselves relative to other amputees rather than to the average healthy person. Frequency measures of affect avoid some of the issues of scale norming. These measures gauge the amount of time a person experiences positive affect versus negative affect. The valence of an event (i.e., positive versus negative) is also less subject to scale norming (Diener, Larsen, Levine, & Emmons, 1985). Thus, these methodological issues are not insurmountable.

Finally, social desirability may play a role in adaptation to life events (Frederick & Loewenstein, 1999). People may exaggerate their level of happiness after a positive event, such as marriage, because they believe it is expected of them. By the same token, people may minimize the amount of adaptation they have experienced to a negative event, such as the death of a spouse or a messy divorce, which they are expected to grieve. Findings regarding the length of time it takes to adapt to events may therefore be biased. However, this problem may be minimized—although not eliminated—by asking questions in such a way as to not draw attention to the purpose of the study. For example, large-scale longitudinal panel studies contain many questions, so participants are unlikely to observe a connection between measures of well-being and questions about their life status (e.g., marriage, job loss), and thus are somewhat less likely to be influenced by social desirability.

Evidence Supporting Hedonic Adaptation

Adaptation to Negative Events

Negative events—both large and small—are a normal part of daily life. Even minor negative events can impact a person’s mood and can sometimes feel overwhelming (Kanner, Coyne, Schaefer, & Lazarus, 1981). Major events, on the other hand, can be traumatic. Nevertheless, people show a remarkable capacity to adapt even to major negative events.

Disability. Disability is a negative life event that can impact almost every aspect of an individual’s life. Most people imagine that it must be extremely difficult, if not impossible, to adapt to disability. However, research suggests that people who experience a new disability do recover somewhat, although not completely, from the event (Lucas, 2007). In a 19-year panel study, participants’ well-being was measured for several years before and after a disability was incurred. As such, researchers were able to observe whether the change in well-being was due to pre-event levels of happiness or the disability itself. Disabled people showed a significant decline in happiness in the first year of the disability, but, over time, their levels of well-being gradually approached their baseline. However, this adaptation was not complete, and individuals did not return to their initial happiness levels, even when controlling for changes in employment status and income. Furthermore, not surprisingly, participants with severe disabilities experienced a larger drop in well-being—and developed a lower baseline for happiness—compared to those with mild disabilities. This pattern is likely due to the number and magnitude of negative events associated with severe disabilities, such as the need for caretaking.

Divorce. In the United States, nearly half of all first marriages end within 20 years (Copen, Daniels, Vespa, & Mosher, 2012). As such, it is important to understand the lasting hedonic impact of divorce. An 18-year panel study (Lucas, 2005) found that people began to decline in well-being in the years before a divorce. Following the divorce, they gradually began to return toward their baseline levels of happiness, with changes in well-being leveling off approximately 5 years later. However, participants in this study did not return to their initial levels of happiness, suggesting that, on average, they only partially adapted to divorce. Another investigation, however, found that individuals adapted to divorce both rapidly and completely (Clark, Diener, Georgellis, & Lucas, 2008).

The circumstances surrounding a divorce may influence a person’s rate or degree of adaptation (Lucas, Clark, Georgellis, & Diener, 2003). For example, one investigation found that those who did not remarry during the course of the study showed longer-lasting declines in well-being than those who remarried (Lucas, 2007). These individual differences may help explain why some people return to their baseline level of happiness following a divorce, whereas others never fully adapt.

Widowhood. Widowhood can be a traumatic life event. Research shows that after the death of a spouse, people experience a significant decline in well-being (Lucas & Clark, 2006). This impact on well-being begins to dissipate approximately 2 years after the loss. As time passes, widows and widowers gradually approach their initial level of happiness but do not completely return to it, even 8 years after losing their spouse (however, see Clark et al., 2008, for evidence of complete adaptation). Researchers found that people’s reactions to widowhood impacted their degree of adaptation, such that a more positive immediate reaction was associated with greater adaptation (Lucas et al., 2003).

Other individual differences undoubtedly play a role in the extent to which people adapt to widowhood. One study found that individuals whose spouses were seriously ill prior to death were more likely to be depressed, to rate their spouses negatively, and to show improvement after the death of their spouses (Bonanno et al., 2002). Individuals in this situation would most likely show complete adaptation to widowhood. By contrast, those who were dependent on their spouses for both emotional and financial resources would likely never fully adapt.

Unemployment. In today’s economy, unemployment has become a common occurrence. Research has shown that after people become unemployed, they experience a decline in happiness, followed by an approach to baseline (Clark & Georgellis, 2013; Lucas, Clark, Georgellis, & Diener, 2004). Interestingly, however, such individuals never fully reach their baseline levels of happiness, providing evidence for partial adaptation. Furthermore, the effect of unemployment on well-being may last much longer than the unemployment itself: people do not fully adapt to becoming unemployed even after being re-employed (Lucas et al., 2004).

People’s initial reactions to the unemployment may impact the process of adaptation, such that the more negatively individuals react to unemployment, the less they eventually adapt to it (Lucas et al., 2004).

Adaptation to Positive Events

Negative life events undoubtedly play a major role in happiness and its pursuit, as people try to protect their well-being by anticipating them, avoiding them, and trying to adapt or cope with them. Positive life events play a distinct role in the pursuit of happiness because many believe that the secret to happiness is simply to experience more positive events and achieve their goals, like getting married, having kids, and striking it rich (Lyubomirsky, 2013). In other words, people tend to focus on trying to change their life circumstances in order to achieve greater happiness. Although the attainment of major life goals is indeed associated with increased well-being (Brunstein, 1993; Sheldon & Elliot, 1998, 1999; Sheldon & Kasser, 1998), unfortunately people can become accustomed to positive life changes in much the same way that they become accustomed to negative ones.

Marriage. Approximately 90% of people eventually get married (Myers, 2000). A meta-analysis revealed that marriage is associated with relatively higher well-being (Haring-Hidore, Stock, Okun, & Witter, 1985). According to Clark and Georgellis (2012), people generally experience a boost in happiness prior to marriage as they become engaged, anticipate their wedding, and eventually get married. Over time, however, people eventually return to their initial level of happiness. In fact, on average, individuals were found to fully adapt to marriage within 2 years (Clark & Georgellis, 2013; Clark et al., 2008).

Despite findings of adaptation to marriage, individual differences are likely to be present. One 15-year longitudinal study explored individual differences in rates of adaptation to marriage (Lucas et al., 2003). Researchers found that adaptation depended on participants’ initial reactions to marriage. Newlyweds who showed a strong positive reaction to marriage were better able to maintain their boost in well-being than those who reacted less strongly or negatively. Interestingly, participants who reported higher well-being at baseline were relatively less likely to react very positively to marriage. One possible reason is the boost in social support that new marriage delivers. Research has found happier people to have stronger support networks (Myers, 2000). Unhappy people may, therefore, react more positively to the social support that their spouses provide because they are not getting that support elsewhere.

New job. Beginning a new job can be a very exciting time in a person’s life, particularly in the current economy. One study, however, found evidence for complete adaptation to making a job change (Boswell, Boudreau, & Tichy, 2005). In this study, a job change was defined as either a promotion in the same organization or voluntarily leaving one’s job for a position elsewhere. In the year prior to changing jobs, managers reported relatively low job satisfaction, possibly due to increasing dissatisfaction with their current job, which may have ultimately motivated them to look for a change (Griffeth, Hom, & Gaertner, 2000). Boswell and his colleagues found, as expected, that managers experienced a surge in job satisfaction immediately after starting their new position. However, within the following year, their well-being fell back to their initial levels.

Interestingly, this same study found that individuals who changed jobs multiple times followed the same pattern with each subsequent job change. That is, each job change was associated with a boost in well-being followed by a return to baseline. One reason for this pattern is that each career move led to meeting new people and facing new job opportunities and challenges—exciting at first but associated with diminished positive emotions over time. Furthermore, managers may have declined in well-being due to escalating aspirations. During the interview process, employers tend to focus on the positive attributes of the job (e.g., 24-hour gym, child care; Ilgen, 1971) and new employees may quickly take these attributes for granted and soon desire even more.

Birth of a child. The birth of a child is a long-awaited and joyous event for many couples. In one investigation, women reported higher well-being up to 3 years before the birth of a child, perhaps as they anticipated the joys of motherhood (Clark & Georgellis, 2013). However, they rapidly reverted to their baseline levels of happiness shortly after the birth of the child. By contrast, men did not experience a significant boost in happiness. Other research has found evidence that although women experienced a greater surge in happiness, men and women showed comparable patterns of anticipation and adaptation (Clark et al., 2008). Similarly, in a 22-year panel study, both parents experienced a boost in well-being immediately following the birth of a child, but returned to their baseline levels of well-being within 2 years, suggesting that parents react similarly to parenthood (Dyrdal & Lucas, 2013). However, this study also found individual differences in rates of adaptation. For example, parents with high initial levels of well-being experienced a smaller boost in happiness after becoming a parent and decreased more in happiness after their child’s birth, compared to those with lower baseline levels of well-being. In addition, new parents who reacted more positively to the birth of the child maintained their happiness boost much longer than those who reacted less strongly.

A meta-analysis of this literature found divergent effects of childbirth on well-being depending on the component of well-being—cognitive (e.g., life satisfaction) versus affective (e.g., positive emotions)—that was measured (Luhmann, Hofmann, Eid, & Lucas, 2012). On average, parents reported receiving a boost in life satisfaction after the birth of the child, followed by a rapid decrease back toward baseline. At the same time, parents reported experiencing fewer positive emotions immediately following the birth of their child, but the number of positive emotions increased over time. These findings suggest that although parents quickly return to their initial levels of life satisfaction, they also experience an increasing number of positive emotions associated with parenthood.

Cosmetic surgery. Nearly 6.5 million aesthetic surgeries are performed worldwide every year (International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, 2011). This statistic indicates that a large number of people seek to improve some aspect of themselves through surgery. One study found that participants who received cosmetic surgery experienced more positive outcomes than those who did not undergo surgery but were similarly dissatisfied with a particular physical feature (Margraf, Meyer, & Lavallee, 2013). Furthermore, surgery patients reported maintaining their boost in well-being up to a year later. The investigators found that participants reported an increase in self-esteem after the surgery, and this increased self-esteem may have pushed them to seek out experiences and friendships they were previously hesitant to pursue. Although this study did not find evidence of adaptation, it is possible that participants would begin to decline in well-being several years after receiving the cosmetic surgery, as the events and emotions associated with the surgery may take more time to become accustomed to. For example, after cosmetic surgery, a man may receive many compliments, which gives him the confidence to meet new people, become active in new activities, and seek out more challenging career opportunities. Cosmetic surgery may, therefore, lead to a series of new positive events and emotions, thus slowing adaptation.

Hedonic Adaptation Prevention Model

In an ideal world, people would fully adapt to negative life changes and experience sustained well-being from positive life changes. Although individuals do adapt to adverse events, this adaptation is often incomplete. Furthermore, people appear to adapt much more quickly and completely to positive events—a phenomenon that functions as an obstacle to achieving lasting happiness. As a result, research has begun to focus on ways to thwart hedonic adaptation to positive events.

The rate of adaptation varies for both positive and negative events. Some people appear to adapt quickly to changes in their lives, whereas others adapt much more slowly. These differences may be due to variation in the activities that individuals engage in following a circumstantial change. The Hedonic Adaptation Prevention (HAP) model and its variants (Lyubomirsky, 2011; Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, 2012) (this model used to be called the Hedonic Adaptation to Positive and Negative Events model, but now we refer to it as the Hedonic Adaptation Prevention model) explain how and why people adapt to both positive and negative changes in their lives and identify ways in which they can incorporate different activities into those changes in order to influence the rate of adaptation (see Figure 4.1 for the model’s depiction of positive adaptation). In this chapter, we primarily focus on adaptation to positive events, proposing how people may be able to gain the maximum level of happiness from the good things in their lives.

In short, the HAP model posits that adaptation proceeds via two separate paths, such that initial happiness gains keyed to a positive life change (e.g., a new romance or job) are eroded over time. The first path specifies that the stream of positive emotions and events resulting from the positive life change may lessen over time, sending people’s happiness levels back to their baseline. The second, more counterintuitive, path specifies that the stream of positive events resulting from the change may increase people’s aspirations about the positivity of their lives, such that circumstances that used to produce happiness are now taken for granted; the person wants more. Furthermore, the HAP model suggests two important moderators of the hedonic adaptation process. First, the more variable (and perhaps surprising) one’s positive events, the more likely they’ll produce frequent positive emotions and sustained well-being and the less likely they’ll raise one’s aspiration level. Second, the model specifies that continued appreciation of the positive change can forestall rising aspirations and thus thwart adaptation.

Sheldon and Lyubomirsky (2012) have found evidence to support the complete HAP model. Participants were initially asked to fill out baseline measures of well-being. Six weeks later, they were instructed to reflect on a positive life change that had recently occurred. Participants reported a boost in happiness after the positive life change. However, the researchers also found differences in the rates of adaptation to positive life changes, suggesting variations in the behaviors of participants who adapted quickly versus slowly. Accordingly, the HAP model explains how a positive life change that occurred at the beginning of the study can have lasting effects on one’s happiness 6 weeks later.

Mediators of the Hedonic Adaptation Process

A positive change in one’s life is associated with a stream of positive events and emotions (Lyubomirsky, 2011). As people adapt to this life change, they form expectations that eventually alter the experience of the associated positive events.

Positive emotions and events. As mentioned previously, one pathway by which people adapt to positive changes is through declining positive emotions and events (see Figure 4.1, bottom path; Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, 2012; Lyubomirsky, 2011). When individuals experience a positive change, they also experience an increase in positive emotions and events connected to this change. For example, after marriage, people encounter a lot of new and exciting events. They may go on a honeymoon to a romantic location they have never visited before or create a home together. They may also receive a lot of attention and positive reactions from family and friends. These positive events give rise to more positive emotions, such as excitement, joy, and love. As time passes, however, the positive events and emotions become less common and less novel. Furthermore, people may begin to take these events and emotions for granted, and they become the new standard or “new normal” (Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, 2012). Although people still encounter positive events associated with the initial change (the marriage), those events may decline in positivity over time ( Lyubomirsky, 2011). As such, the initial boost begins to wear off, and the newlyweds begin to adapt. Sheldon and Lyubomirsky (2012), in the study described earlier, found that participants who continued to experience positive events and emotions associated with their initial life change reported higher well-being at the end of the study than those who did not. This finding suggests that positive events should be optimized to slow down adaptation.

Aspirations. Increasing aspirations are another way in which people adapt to positive changes (see Figure 4.1, top path; Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, 2012). As people become accustomed to the events associated with their positive change, they begin to require more to sustain the same level of happiness. For example, a woman whose husband washes the dishes every day would come to expect it. She may then begin to want him to do more work around the house, such as vacuuming the living room or cleaning the bathrooms, to get the same delight and satisfaction she felt when her husband first began helping with the housework. People may also show increasing desires for more following a job promotion. After the employee adapts to the positive events surrounding a promotion, he may begin to aspire for an ever higher income or more authority over his subordinates. In many cases, these aspirations can no longer be fulfilled and the person’s well-being declines. Thus, aspirations can be a barrier to sustainable happiness.

In the Sheldon and Lyubomirsky study (2012), as hypothesized by the HAP model, rising aspirations predicted lower well-being at the 6-week follow-up. Accordingly, this route should be minimized to impede adaptation to positive life changes. However, one set of studies found no relationship between well-being and height of aspirations (Jacobs Bao, Layous, & Lyubomirsky, 2013). A more important factor seemed to be whether or not participants were able to fulfill their aspirations. In this study, higher aspirations were found to be harmful when they could no longer be fulfilled. At some point, the aspirations may become too high, and people are eventually unable to fulfill them.

Moderators of the Hedonic Adaptation Process

Variety. People adapt most easily to constant stimuli, rather than to changing, unpredictable stimuli (Lyubomirsky, 2011). Constant stimuli lack novelty, allowing them to fall out of one’s awareness. Over time, the positive events that arise as a result of making a life change become predictable and expected, and as such, they no longer contribute to one’s well-being. Supporting the HAP model (see top left, Figure 4.1), Sheldon and Lyubomirsky (2012) found that greater variety in one’s positive events tempered aspirations. Accordingly, greater variety allowed people to remain satisfied with their life change. For example, if a new homeowner experiences many varied events, such as neighborhood strolls and block parties, she will not feel the need to move to an even better location. Indeed, the effect of emotions on well-being was found to be greater when the events experienced after a life change were characterized by a high level of variety, suggesting that variety moderates the relationship between positive life changes and well-being.

More evidence for the importance of variety in impeding adaptation comes from a 6-week-long intervention in which participants were randomly assigned to make a dynamic and variable life change versus a static, one-time change. Participants who reported that their change added variety to their lives experienced the greatest increase in well-being (Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, 2009). Greater variety in events associated with a life change also allows people to maintain their boost in happiness. For example, participants who reported greater variety in a recent life change maintained the boost in well-being more than those who reported less variety (Sheldon, Boehm, & Lyubomirsky, 2012). Finally, another investigation by the same authors found that participants who were randomly assigned to vary acts of kindness that they performed for people in their lives maintained their boost in happiness better than those who did not vary them. These studies support the moderating role of variety in the adaptation process (see Figure 4.1, bottom).

Variety increases the complexity of a situation, thereby making it more interesting (Berlyne & Boudewijns, 1971) and allowing individuals to maintain their curiosity and awareness. Increased interest and curiosity may help explain why research has found that experiencing more variety in the events surrounding a positive life change diminishes the likelihood of rising aspirations (Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, 2012). Individuals will not covet even more desirable life changes if their current life change is still able to maintain their attention.

Experiences characterized by more variety are associated with higher happiness levels than those characterized by less variety (cf. Van Boven, 2005; Van Boven & Gilovich, 2003). For example, during a sightseeing vacation, people may be more likely to partake in activities that they do not normally choose and encounter many unexpected events. In contrast, material purchases, such as a new couch, are not generally dynamic or surprising. After the person becomes accustomed to her new couch, there is nothing new and exciting about it, and the object no longer produces boosts in happiness. One reason that vacations are associated with greater happiness boosts than material purchases may be that the former offer more variety.

Surprise. As a close cousin of variety, surprise is also important in thwarting adaptation, perhaps because surprising events are not easily understood (Wilson & Gilbert, 2008). For example, a new bride whose husband plans surprise trips or occasionally brings flowers “just because” will not show adaptation to her marriage as quickly. She will not have a ready answer for why her husband is planning these events, and he will keep her guessing about what might come next. Indeed, the initial surprise of a marriage proposal and the sheer number of new and varied events that occur during the engagement period may be one reason that couples’ well-being soars prior to marriage. A surprising event is often hard to explain away. In one study, researchers randomly approached people at a library and gave them a dollar coin with an attached card (Wilson, Centerbar, Kermer, & Gilbert, 2005). In the “uncertain” condition, the card explained that the researcher was from a society that committed random acts of kindness. This vague information prevented participants from easily explaining why they received the money. The “certain” condition involved a card that explained to participants why they were given a dollar. The researchers found that those who could not be certain of why they received the money experienced a greater increase in positive mood. Surprise keeps things exciting and fresh, allowing the person to remain content with what she has.

Another study found that participants who received surprising personal feedback (e.g., “Your biggest strength is humor”) continued to increase in well-being even after the study was over, whereas those who were not surprised by the feedback did not show this boost (Jacobs Bao, Boehm, & Lyubomirsky, 2013). Incorporating variety and surprise into the events surrounding the positive change can thus help thwart adaptation (Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, 2012).

Appreciation. People who experience higher levels of appreciation toward a positive life change adapt more slowly (Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, 2012). Appreciating a fortunate life turn forces people to attend to it and notice all of the nuances associated with it. As such, they are also less likely to aspire for something even better. The more people appreciate an event, the more reasons they may find to feel happy as a result of it. A person who appreciates his wife and new marriage is less likely to take the things she does for granted. Instead, he may feel lucky that he has her in his life. As such, he would experience the higher levels of well-being associated with newly married life for longer. Failure to appreciate a positive change is a sign that the individual no longer notices or pays heed to that change, which signals complete adaptation. In support of this idea, Sheldon and Lyubomirsky (2012) found that people who reported higher levels of appreciation for their life change also showed lower aspirations and higher well-being (see appreciation depicted as a moderator in Figure 4.1). Thus, appreciation can help thwart adaptation.

According to Kahneman and Thaler (2006), life circumstances (e.g., a new car or job) continue to influence a person’s well-being for as long as they draw his attention. As he adapts to the car or job, however, the novelty wears off and they fade into the background of his awareness. One study found that those who continued to be aware of their positive life changes adapted less quickly to them (Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, 2009). Therefore, maintaining one’s attention on a life change—whether by appreciating it or simply focusing on it—is another way to forestall adaptation.

Hedonic Adaptation to Negative Life Changes

Although much of our discussion has focused on adaptation to positive life changes, the HAP model can also explain adaptation to the negative (see Lyubomirsky, 2011, for a detailed discussion). A critical difference is that after experiencing a negative life change, people are usually interested in speeding up the adaptation, not slowing it down.

People become accustomed to negative life changes in much the same way they do to positive ones (Lyubomirsky, 2011). Over time, the negative events associated with a negative life change—e.g., downsizing to a smaller house or leaving one’s spouse—become less unexpected. Accordingly, these events trigger fewer and less intense negative emotions. At the same time, people tend to lower positive aspirations about their lives. Adaptation to negative life changes is therefore characterized by experiencing fewer negative emotions and decreasing aspirations.

If an individual’s goal is to return to his baseline level of happiness after experiencing a negative event, he must apply what is known about thwarting hedonic adaptation in a different way (Lyubomirsky, 2011). For example, experiencing more variable and unexpected events can help thwart adaptation to both positive and negative life changes. Therefore, minimizing the variety and surprise associated with a negative life change should accelerate adaptation. Furthermore, events continue to impact well-being for as long as they capture people’s attention. Although maintaining awareness and attention to positive events has been found to be beneficial, this attention—if it involves systematic analysis—may also lead people to understand these events, thus allowing them to adapt (Lyubomirsky, Sousa, & Dickerhoof, 2006). As such, this phenomenon may be beneficial in accelerating adaptation to negative events by helping people understand, explain, and come to terms with a negative event. People can also accelerate adaptation by laboring to reduce their aspirations. For example, after a breakup, a woman can work at accepting the loss of her former significant other and focus on the benefits of being single. In sum, by bringing the HAP model to bear on both good and bad turns of events, people can learn to thwart adaptation to positive changes in their lives and accelerate adaptation to negative ones.

Future Directions and Questions

Our research team has been investigating the sustainability of positive changes in well-being for more than a decade. The HAP model, described here, represents the current culmination of this thinking. As described previously, Sheldon and Lyubomirsky (2012) provided the best evidence to date for the HAP model, via a sophisticated longitudinal test of the model in the context of naturally occurring data. However, much more research—especially experimental research—remains to be done. Any of the factors identified in the HAP model might be manipulated experimentally, including manipulations of initial positive life changes (e.g., by inducing participants to commence a rewarding new activity), manipulations of the number and quality of positive events resulting from these changes, manipulations of the variety or surprisingness of those events, manipulations of appreciation for the initial changes, and manipulations that prompt increasing (or decreasing) aspirations for more of the events (e.g., via provision of social comparison information). As we more fully develop and test the HAP model, we are striving to move beyond self-reports of happiness, to ensure that the processes the model describes are observable to others and are not accounted for by self-report biases.

We are also interested in a variety of broader questions that emerge from our approach. One concerns “optimal negativity.” Are there some conditions under which momentary negative experiences should be focused on—and their well-being consequences suffered—in service of greater well-being in the future? Feeling genuine chagrin for one’s mistakes (such as speaking harshly to a child), and feeling the guilt and remorse that accompany those mistakes, may guide better decision making in the future. Perhaps one should not adapt to such chagrin or remorse too quickly. More generally, is there an ideal ratio of positive to negative experience that promotes maximal long-term well-being, besides “all positive” and “no negative”? Fredrickson and Losada (2005) argued that there may be such a ratio, but more recent work has called their proposed ratio into question (Brown, Sokal, & Friedman, 2013). To date, little evidence indicates that negative experiences have positive functions, but intuition suggests otherwise.

Another theoretical issue concerns the half-life of positive events. In essence, the HAP model describes how to “milk” a positive life change to maximize the duration of its effect on happiness. For some positive changes, this process may be essentially never-ending (i.e., one can continue to derive hedonic benefits from one’s long-term partner throughout one’s life), but other life changes have a statute of limitations, as it were. Perhaps a person can appreciate the new painting or the new job for only so long before its potential to affect him is exhausted and he needs to go out and procure another painting or another job. We certainly do not advocate that people stick it out rigidly in formerly rewarding situations or relationships after “the thrill is gone;” instead, we advocate exploring whether the thrill can be rekindled, using the recommendations of our model, before deciding to move on.

In a related vein, we do not advocate that people never “aspire for more” than their current situation or set of skills or occupations. Obviously, future aspirations are a large part of what drives sustained effort, goal attainment, and personal growth (Sheldon & Elliot, 1999). Although a Buddhist perspective may eschew such aspirations, we do not. Instead, we caution against allowing one’s aspirations to creep up before one has experienced the full potential enjoyment of what one already has. Rising aspirations (as in rising materialism or rising consumption) should not be a mindless coping strategy to manage internal restlessness; instead, rising aspirations should occur only after the statute of limitations has expired on one’s current status quo. Determining the when, how, and why of such inflection points remains a major challenge for future research.

Conclusion

People have a remarkable capacity to adapt to changes in their lives—a capacity that compels them to return to their prior emotional baselines. This process, however, appears to be asymmetric across positive and negative domains. Although individuals show some adaptation to negative life changes, they often never completely return to their initial level of happiness following traumatic events. This evidence suggests that, in answer to this book’s titular question, “well-being can change”—but, unfortunately, not in the direction most would prefer! Furthermore, people appear to adapt much more quickly and completely to positive life changes than negative ones. This evidence demonstrates that the average person does not obtain sustainable pleasure from her positive life changes—no matter how wonderful they may be initially—thwarting her goal to become lastingly happier. Taken together, evidence concerning greater adaptation to positive than to negative life changes breeds pessimism about whether sustainable positive change in well-being is even possible.

Fortunately, the HAP model suggests ways for individuals to obtain longer-lasting boosts in well-being from the positive changes in their lives. Increasing the variety and surprisingness of the positive events deriving from any pleasant life change helps maintain an inflow of momentary positive experiences and helps prevent rising aspirations for more and more. Furthermore, truly appreciating a life change helps people be content with what they have and prevents them from prematurely increasing their desires for something better. Thus, research supporting the HAP model suggests that, at least up to some as yet undetermined limit, sustainable positive change in well-being is indeed possible, if the person lives her life in the right way. However, it is not necessarily easy to accomplish this. Effort and some degree of mindfulness are both essential. Fortunately, the “work” of positive living is likely to be inherently engaging and reinforcing, once the right habits are acquired.