Increasing Happiness by Well-Being Therapy

Chiara Ruini and Giovanni A. Fava, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy

In this chapter we examine the clinical implications of happiness and psychological well-being. A specific psychotherapeutic strategy for increasing psychological well-being, well-being therapy (WBT), is described with special reference to the promotion of an individualized and balanced path to achieve happiness and optimal human functioning, avoiding the polarities in positive psychological dimensions. WBT has been tested in a number of randomized controlled trials. The findings indicate that optimal human functioning can be promoted by specific interventions leading to a positive evaluation of one’s self, a sense of continued growth and development, the belief that life is purposeful and meaningful, the possession of quality relations with others, the capacity to manage effectively one’s life, and a sense of self-determination. Such modifications are associated with enduring benefits.

Keywords

well-being therapy; happiness; affective disorders; psychotherapy; remission; resilience

Introduction

In 1989, in a pioneer work titled “Happiness Is Everything or Is It?” Ryff argued that, when dealing with human existence, the concept of happiness should be better defined and articulated than the simple presence of pleasure and positive affect. Ryff (1989) developed a model of positive human functioning that she called psychological well-being (PWB). It could be briefly regarded as the engagement with and participation in the existential challenges and opportunities of life, where human beings enjoy the exercise of their realized capabilities.

Some years later, Ryan and Deci (2001) examined the concept of well-being and described two main approaches: the hedonic and the eudaimonic one. According to the former, well-being consists of subjective happiness, pleasure, and pain avoidance. Thus, the concept of well-being is equated with the experience of positive emotions versus negative emotions and with satisfaction in various domains of one’s life. This hedonic point of view concentrated on happiness as the result of experiencing pleasant emotions, low levels of negative moods, and high levels of perceived life satisfaction. It has been identified with the term subjective well-being for indicating a person’s cognitive (life satisfaction) and affective evaluation (pleasant and unpleasant affect) of her or his life: a subjective evaluation and a condition for a good life.

According to the eudaimonic perspective, happiness consists of fulfilling one’s potential in a process of self-realization. Under this umbrella, some researchers describe concepts such as fully functioning person, meaningfulness, self-actualization, and vitality. Importantly, in describing optimal human functioning, Ryff and Singer (2008) emphasize Aristotle’s admonishment to seek “that which is intermediate,” avoiding excess and extremes. The pursuit of well-being may, in fact, be so solipsistic and individualistic to leave no room for human connection and the social good, or it could be so focused on responsibilities and duties outside the self that personal talents and capacities are neither recognized nor developed (Ryff & Singer, 2008).

These two approaches have led to different areas of research, but they complement each other in defining the construct of well-being (Ryan & Deci, 2001). Some authors have also suggested that they can compensate each other; thus, individuals may have profiles of high eudaimonic well-being and low hedonic well-being, or vice versa. These profiles are also associated with sociodemographic variables, such as age, years of education, and employment (Keyes, Shmotkin, & Ryff, 2002). However, in this investigation, the authors underlined the fact that only a small proportion of individuals present optimal well-being—that is, high hedonic and eudemonic well-being—paving the way for possible psychosocial interventions. The findings that we are going to analyze indicate that the two viewpoints are inextricably linked in clinical situations, and the extent, number, and circumstances of changes in well-being induced by treatments may matter more than a priori distinctions.

The Concepts of Happiness and Well-being in Clinical Psychology

In clinical psychology, the eudaimonic view has found much more feasibility, compared to the hedonic approach, because it concerns human potential and personal strength (Ryff & Singer, 1996; 2008). Ryff’s model of psychological well-being, encompassing autonomy, personal growth, environmental mastery, purpose in life, positive relations, and self-acceptance, has been found to fit specific impairments of patients with affective disorders (Fava et al., 2001; Rafanelli et al., 2000). Further, the absence of psychological well-being was found to be a risk factor for depression (Wood & Joseph, 2010). Thunedborg, Black, and Bech (1995) observed that quality of life measurement, and not symptomatic ratings, could predict recurrence of depression. An increase in psychological well-being may thus protect against relapse and recurrence (Fava, 1999; Wood & Joseph, 2010). Therefore, an intervention that targets the positive may address an aspect of functioning and health that is typically left unaddressed in conventional treatments.

Increasing Happiness by Targeted Interventions: Is “Happier Always Better”?

Ryff and Singer (1996) underlined that interventions that bring a person out of negative functioning are one form of success, but facilitating progression toward the restoration of positive is quite another. Parloff, Kelman, and Frank (1954) suggested that the goals of psychotherapy were increased personal comfort and effectiveness, and humanistic psychology suggested concepts such as self-realization and self-actualization as final therapeutic goals (Maslow, 1968; Rogers, 1961). For a long time, these latter achievements were viewed only as by-products of the reduction of symptoms or as a luxury that clinical investigators could not afford. This probably is due to the fact that, historically, mental health research was dramatically weighted on the side of psychological dysfunction, and health was equated with the absence of illness, rather than the presence of wellness (Ryff & Singer, 1996). Ryff and Singer (1996) suggested that the absence of well-being creates conditions of vulnerability to possible future adversities and that the route to enduring recovery lies not exclusively in alleviating the negative, but in engendering the positive.

Early pioneer works in this research domain can be considered Ellis and Becker’s (1982) guide to personal happiness, Fordyce’s (1983) program to increase happiness, Padesky’s (1994) work on schema change processes, Frisch’s (1998; 2006) quality of life therapy, and Horowitz and Kaltreider’s (1979) work on positive states of mind.

More recently, a growing number of investigations on positive emotions (Fredrickson & Joiner, 2002); subjective well-being (Diener, 2000; Diener, Suh, Lucas, & Smith, 1999); human strengths (Peterson & Seligman, 2004); and other positive personality characteristics such as compassion, hope, and altruism (Park, Peterson, & Seligman, 2004) paved the way for developing “positive interventions” (Magayar-Moe, 2009; Seligman, Steen, Park, & Peterson, 2005; Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009). These interventions include positive psychotherapy (Seligman, Rashid, & Parks, 2006); wisdom psychotherapy (Linden, Baumann, Lieberei, Lorenz, & Rotter, 2011); gratitude interventions (Wood, Maltby, Gillett, Linley, & Joseph, 2008); positive coaching (Biswas-Diener, 2009; 2010); strengths-based approaches (Biswas-Diener, Kashdan, & Minhas, 2011; Govindji & Linley, 2007; Linley & Burns, 2010); hope therapy (Geraghty, Wood, & Hyland, 2010; Snyder, Ilardi, Michael, Yamhure, & Sympson, 2000); and forgiveness therapy (Lamb, 2005).

In a recent meta-analysis, Bolier et al. (2013) showed that these positive psychology interventions significantly enhance subjective and psychological well-being and reduce depressive symptoms, even though effect sizes were in the small to moderate range. Further, the majority of positive psychology interventions considered in this meta-analysis (26 out of 39 studies) were delivered in a self-help format, sometimes in conjunction with face-to-face instruction and support, and on very heterogeneous groups. Even though self-help suits the goals of positive psychology very well, and indeed is highly standardized, it often takes a “one size fits all” approach, which may underestimate the complexity of phenomena in clinical settings and not fully consider the balance between positivity and distress (Rafanelli et al., 2000; Ruini & Fava, 2012).

The main aim of all these positive interventions, in fact, is the promotion of happiness, positive emotions, and positivity in general. This is based on the assumption that the benefits of well-being are now well documented in cross-sectional and longitudinal research and include better physical health (Chida & Steptoe, 2008; Fava & Sonino, 2010; Howell, Kern, & Lyubomirsky, 2007), improved productivity at work, more meaningful relationships, and social functioning (Seeman, Singer, Ryff, Dienberg, Love, & Levy-Storms 2002). In the same line, research has indeed suggested the important role of positive affectivity (Fredrickson & Joiner, 2002) in promoting resilience and growth.

However, specific dimensions of positive functioning, namely, autonomy and independence, have been determined to be related to increased levels of noradrenaline (Seeman et al., 2002) and seem thus to be associated with an increased stress response. Similarly, excessively elevated levels of positive emotions can become detrimental and are more connected with mental disorders and impaired functioning (Fredrickson & Losada, 2005). Larsen and Prizmic (2008) argued that the balance of positive to negative affect (i.e., the positivity ratio) is a key factor in well-being and in defining whether a person flourishes. Several authors (Fredrickson & Losada, 2005; Larsen & Prizmic, 2008; Schwartz, 1997; Schwartz et al., 2002) suggest that, to maintain an optimal level of emotional well-being and positive mental health, individuals need to experience approximately three times more positive than negative affect. Fredrickson and Losada (2005), in fact, have found that above this ratio, there is an excessively high positivity that becomes detrimental to functioning. Excessive positivity in adverse situations, in fact, can signal inappropriate cues to thoughts and action (Fredrickson & Losada, 2005) or may be accompanied by illusions that are easily shattered by the harsh, hostile reality (Shmotkin, 2005). Garamoni et al. (1991) suggested that healthy functioning is characterized by an optimal balance of positive and negative cognitions or affects, and that psychopathology is marked by deviations from the optimal balance.

Positive interventions, thus, should not be simply aimed to increase happiness and well-being, but should consider the complex balance between psychological well-being and distress (MacLeod & Moore, 2000) and be targeted to specific and individualized needs. Wood and Tarrier (2010) emphasized that positive characteristics such as gratitude and autonomy often exist on a continuum. They are neither “negative” or “positive”: their impact depends on the specific situation and on the interaction with concurrent distress and other psychological attitudes. For instance, self-efficacy beliefs (Caprara, Alessandri, & Barbaranelli, 2010; Karlsson et al., 2011) and emotional inhibition (Grandi, Sirri, Wise, Tossani, & Fava, 2011) may affect the expression of positive orientation.

All these elements should be taken into account in the psychotherapy process. An example of psychotherapeutic intervention that takes into consideration the preceding concepts for achieving a balanced and individualized path to optimal functioning is well-being therapy (WBT; Fava, 1999; Ruini & Fava, 2012).

The Structure of Well-being Therapy

Well-being therapy is a short-term psychotherapeutic strategy that extends over 8 to 12 sessions, which may take place every week or every other week (Fava, 1999; Fava & Ruini, 2003; Ruini & Fava, 2012). The duration of each session may range from 30 to 50 minutes. It is a technique that emphasizes self-observation (Emmelkamp, 1974), with the use of a structured diary and interaction between patients and therapists. Well-being therapy is based on Ryff’s cognitive model of psychological well-being (Ryff, 1989), encompassing six dimensions of positive functioning and eudaimonic well-being: autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, purpose in life, self-acceptance, and positive interpersonal relationships. The development of sessions is as follows.

Initial Sessions

These sessions are simply concerned with identifying episodes of well-being and setting them into a situational context, no matter how short lived they were. Patients are asked to report in a structured diary the circumstances surrounding their episodes of well-being, rated on a 0–100 scale, with 0 being absence of well-being and 100 the most intense well-being that could be experienced.

Patients are particularly encouraged to search for well-being moments, not only in special hedonic-stimulating situations but also during their daily activities. Several studies have shown that individuals preferentially invest their attention and psychic resources in activities associated with rewarding and challenging states of consciousness, in particular with optimal experience (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). This is characterized by the perception of high environmental challenges and environmental mastery, deep concentration, involvement, enjoyment, control of the situation, clear feedback on the course of activity, and intrinsic motivation (Deci & Ryan, 1985). Cross-sectional studies have demonstrated that optimal experience can occur in any daily context, such as work and leisure (Delle Fave & Massimini, 2003). Patients are thus asked to report when they feel optimal experiences in their daily life and are invited to list the associated activities or situations.

This initial phase generally extends over a couple of sessions. Yet its duration depends on the factors that affect any homework assignment, such as resistance and compliance.

Intermediate Sessions

When the instances of well-being are properly recognized, the patient is encouraged to identify thoughts and beliefs leading to premature interruption of well-being. The similarities with the search for irrational, tension-evoking thoughts in Ellis and Becker’s rational-emotive therapy (1982) and automatic thoughts in cognitive therapy (Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979) are obvious. The trigger for self-observation is, however, different, being based on well-being instead of distress.

This phase is crucial because it allows the therapist to identify which areas of psychological well-being are unaffected by irrational or automatic thoughts and which are saturated with them. The therapist may also reinforce and encourage activities that are likely to elicit well-being and optimal experiences (e.g., assigning the task of undertaking particular pleasurable activities for a certain time each day). Such reinforcement may also result in graded task assignments (Beck et al., 1979), with special reference to exposure to feared or challenging situations, which the patient is likely to avoid. Over time patients may develop ambivalent attitudes toward well-being. They complain of having lost it, or they long for it, but at the same time they are scared when positive moments actually happen in their lives. These moments trigger specific negative automatic thoughts, usually concerning the fact that they will not last (i.e., it’s too good to be true), that they are not deserved by patients, or that they are attainable only by overcoming difficulties and distress. Encouraging patients in searching and engaging in optimal experiences and pleasant activities is therefore crucial at this stage of WBT.

This intermediate phase may extend over two or three sessions, depending on the patient’s motivation and ability, and it paves the way for the specific well-being enhancing strategies.

Final Sessions

The monitoring of the course of episodes of well-being allows the therapist to realize specific impairments in well-being dimensions according to Ryff’s conceptual framework. An additional source of information may be provided by Ryff’s Scales of Psychological Well-Being (PWB), an 84-item self-rating inventory (Ryff, 1989). Ryff’s six dimensions of psychological well-being are progressively introduced to the patients, as long as the material that is recorded lends itself to it. For example, the therapist could explain that autonomy consists of possessing an internal locus of control, independence, and self-determination or that personal growth consists of being open to new experience and considering self as expanding over time, if the patient’s attitudes show impairments in these specific areas. Errors in thinking and alternative interpretations are then discussed. At this point in time, the patient is expected to be able to readily identify moments of well-being, be aware of interruptions to well-being feelings (cognitions), utilize cognitive behavioral techniques to address these interruptions, and pursue optimal experiences. Meeting the challenge that optimal experiences may entail is emphasized, because it is through this challenge that growth and improvement of self can take place.

Well-being Therapy: Clinical Considerations

Cognitive restructuring in well-being therapy follows Ryff’s conceptual framework (Ryff & Singer, 1996). The goal of the therapist is to lead the patient from an impaired level to an optimal level in the six dimensions of psychological well-being. This means that patients are not simply encouraged to pursue the highest possible levels in psychological well-being, in all dimensions, but to obtain a balanced functioning. This optimal-balanced well-being could be different from patient to patient, according to factors such as personality traits, social roles, and cultural and social contexts (Ruini et al., 2003; Ruini & Fava, 2012).

The various dimensions of positive functioning can compensate each other (some being more interpersonally oriented, some more personal/cognitive) and the aim of WBT, such as other positive interventions, should be the promotion of an optimal-balanced functioning between these dimensions, in order to facilitate individual flourishing (Keyes, 2002). This means that sometimes patients should be encouraged to decrease their level of positive functioning in certain domains. Without this clinical framework, the risk is to lead patients at having too high levels of self-confidence, with unrealistic expectations that may become dysfunctional and/or stressful to individuals.

Environmental mastery. This is the most frequent impairment that emerges, that is felt by patients as a lack of sense of control. This leads the patients to miss surrounding opportunities, with the possibility of subsequent regret over them. On the other hand, sometimes patients may require help because they are unable to enjoy and savor daily life, as they are too engaged in work or family activities. Their abilities to plan and solve problems may lead others to constantly ask for their help, with the resulting feeling of being exploited and overwhelmed by requests. These extremely high levels of environmental mastery thus become a source of stress and allostatic load to the individual. Environmental mastery can be considered a key mediator or moderator of stressful life experiences (Fava, Guidi, Semprini, Tomba, & Sonino, 2010). A positive characterization of protective factors converges with efforts to portray the individual as a psychological activist, capable of proactive and effective problem solving, rather than passively buffeted by external forces (Ryff & Singer, 1998), but also capable of finding time for rest and relaxation in daily life.

Personal growth. Patients often tend to emphasize their distance from expected goals much more than the progress that has been made toward goal achievement. A basic impairment that emerges is the inability to identify the similarities between events and situations that were handled successfully in the past and those that are about to come (transfer of experiences). On the other hand, people with levels of personal growth that are too high tend to forget or do not give enough emphasis to past experiences because they are exclusively future-oriented. Negative or traumatic experiences could particularly be underestimated, as a sort of extreme defense mechanism (denial); i.e., “I just need to get over this situation and go on with my life” (Held, 2002; Norem & Chang, 2002). Dysfunctional high personal growth is similar to a cognitive benign illusion, or wishful thinking, which hinders the integration of past (negative) experiences and their related learning process.

Purpose in life. Patients may perceive a lack of sense of direction and may devalue their function in life. This particularly occurs when environmental mastery and sense of personal growth are impaired. On the other hand, many other conditions worthy of clinical attention may arise from too high levels of purpose in life. First of all, individuals with a strong determination in realizing one (or more) life goal(s) could dedicate themselves fully to their activity, thereby allowing them to persist, even in the face of obstacles, and to eventually reach excellence. This again could have a cost in terms of allostatic load and stress. Further, Vallerand et al. (2003) proposed the concept of obsessive passion for describing an activity or goal that becomes a central feature of one’s identity and serves to define the person. Individuals with an obsessive passion come to develop ego-invested self-structures (Hodgins & Knee, 2002) and eventually display a rigid persistence toward the activity, thereby leading to less than optimal functioning. Such persistence is rigid because it occurs not only in the absence of positive emotions and sometimes of positive feedback, but even in the face of important personal costs such as damaged relationships, failed commitments, and conflicts with other activities in the person’s life (Vallerand et al., 2007). The individual engagement for a certain goal could thus become a form of psychological inflexibility (Kashdan & Rottenberg, 2010), which is more connected with psychopathology than well-being. Some individuals, in fact, remain attached to their goals even when they seem to be unattainable, and keep believing that they would be happy pending the achievement of these goals. These mechanisms are associated with hopelessness (Hadley & MacLeod, 2010; MacLeod & Conway, 2007) and parasuicidal behaviors (Vincent, Boddana, & MacLeod, 2004). Further, this confirms the idea that hope, another future-oriented positive emotion, can become paralyzing and hampers facing and accepting negativity and failures (Bohart, 2002; Geraghty et al., 2010).

Autonomy. It is a frequent clinical observation that patients may exhibit a pattern whereby a perceived lack of self-worth leads to unassertive behavior. For instance, patients may hide their opinions or preferences, go along with a situation that is not in their best interests or consistently put their needs behind the needs of others. This pattern undermines environmental mastery and purpose in life, and these, in turn, may affect autonomy because these dimensions are highly correlated in clinical populations. Such attitudes may not be obvious to the patients, who hide their considerable need for social approval. A patient who tries to please everyone is likely to fail to achieve this goal and the unavoidable conflicts that may result in chronic dissatisfaction and frustration. On the other hand, in Western countries particularly, individuals are culturally encouraged to be autonomous and independent. Certain individuals develop the idea that they should rely only on themselves for solving problems and difficulties, and are thus unable to ask for advice or help. Also in this case, an unbalanced high autonomy can become detrimental for social/interpersonal functioning (Seeman et al., 2002). Some patients complain they are not able to get along with other people, work in teams, or maintain intimate relationships because they are constantly fighting for their opinions and independence.

Self-acceptance. Patients may maintain unrealistically high standards and expectations, driven by perfectionistic attitudes (that reflect lack of self-acceptance) and/or endorsement of external instead of personal standards (that reflect lack of autonomy). As a result, any instance of well-being is neutralized by a chronic dissatisfaction with oneself. A person may set unrealistic standards for his or her performance. On the other hand, an inflated self-esteem may be a source of distress and clash with reality, as was found to be the case in cyclothymia and bipolar disorder (Fava, Rafanelli, Tomba, Guidi, & Grandi, 2011; Garland et al., 2010).

Positive relations with others. Interpersonal relationships may be influenced by strongly held attitudes of perfectionism which the patient may be unaware of and which may be dysfunctional. Impairments in self-acceptance (with the resulting belief of being rejectable and unlovable or others being inferior and unlovable) may also undermine positive relations with others. There is a large body of literature (Uchino, Cacioppo, & Kiecolt-Glaser, 1996) on the buffering effects of social integration, social network properties, and perceived support. On the other hand, little research has been done on the possible negative consequences of an exaggerated social functioning. Characteristics such as empathy, altruism, and generosity are usually considered universally positive. However, in clinical practice, patients often report a sense of guilt for not being able to help someone or forgive an offense. An individual with a strong pro-social attitude can sacrifice his or her needs and well-being for those of others, and this in the long run becomes detrimental and sometimes disappointing. This individual can also become overconcerned and overwhelmed by others’ problems and distress and be at risk for burnout syndrome. Finally, a generalized tendency to forgive others and be grateful toward benefactors could mask low self-esteem and low sense of personal worth.

These insights were confirmed by a recent paper (Grant & Schwartz, 2011) suggesting that all positive traits, states, and experiences have costs that, at high levels, may begin to outweigh their benefits, creating the nonmonotonicity of an inverted U. For this reason, traditional clinical psychology has a crucial role in planning and implementing interventions for enhancing positive affect. The important insight that comes from dealing with psychopathology could thus be used in determining the “right” amount of positivity for a certain individual, considering his or her global situation and needs. WBT is an example of this balanced positive clinical approach.

WBT: Validation Studies

Well-being therapy has been employed in several clinical studies. Other studies are currently in progress.

Residual Phase of Affective Disorders

The effectiveness of well-being therapy in the residual phase of affective disorders was first tested in a small controlled investigation (Fava, Rafanelli, Cazzaro, Conti, & Grandi, 1998a). Twenty patients with affective disorders who had been successfully treated by behavioral (anxiety disorders) or pharmacological (mood disorders) methods were randomly assigned to either a well-being therapy or cognitive behavioral treatment (CBT) of residual symptoms. Both well-being and cognitive behavioral therapies were associated with a significant reduction of residual symptoms, as measured by the Clinical Interview for Depression (CID; Guidi, Fava, Bech, & Paykel, 2011; Paykel, 1985) and in PWB well-being. However, when the residual symptoms of the two groups were compared after treatment, a significant advantage of well-being therapy over cognitive behavioral strategies was observed with the CID. Well-being therapy also was associated with a significant increase in PWB well-being, particularly in the personal growth scale.

The improvement in residual symptoms was explained on the basis of the balance between positive and negative affect (Fava et al., 1998a). If treatment of psychiatric symptoms induces improvement of well-being, and indeed subscales describing well-being are more sensitive to drug effects than subscales describing symptoms (Kellner, 1987; Rafanelli & Ruini, 2012), it is conceivable that changes in well-being may affect the balance of positive and negative affect. In this sense, the higher degree of symptomatic improvement that was observed with well-being therapy in this study is not surprising: in the acute phase of affective illness, removal of symptoms may yield the most substantial changes, but the reverse may be true in its residual phase.

Prevention of Recurrent Depression

Well-being therapy was a specific and innovative part of a cognitive behavioral package that was applied to recurrent depression (Fava, Rafanelli, Grandi, Conti, & Belluardo, 1998b). This package also included CBT of residual symptoms and lifestyle modification. Forty patients with recurrent major depression, who had been successfully treated with antidepressant drugs, were randomly assigned to either this cognitive behavioral package including well-being therapy or clinical management. In both groups, antidepressant drugs were tapered and discontinued. The group that received cognitive behavioral therapy–WBT had a significantly lower level of residual symptoms after drug discontinuation in comparison with the clinical management group. Cognitive behavioral therapy–WBT also resulted in a significantly lower relapse rate (25%) at a 2-year follow-up than did clinical management (80%). At a 6-year follow-up (Fava et al., 2004), the relapse rate was 40% in the former group and 90% in the latter.

WBT was one of the main ingredients of a randomized controlled trial involving 180 patients with recurrent depression that was performed in Germany (Stangier et al., 2013). Even though follow-up was limited only to 1 year, the findings indicate that psychotherapy had significant effects on the prevention of relapse in patients at high risk of recurrence.

Loss of Clinical Effect During Drug Treatment

The return of depressive symptoms during maintenance of antidepressant treatment is a common and vexing clinical phenomenon (Fava & Offidani, 2011). Ten patients with recurrent depression who relapsed while taking antidepressant drugs were randomly assigned to dose increase or to a sequential combination of cognitive-behavior and well-being therapy (Fava, Ruini, Rafanelli, & Grandi, 2002). Four out of five patients responded to a larger dose, but all relapsed again on that dose by 1-year follow-up. Four out of the five patients responded to psychotherapy and only one relapsed. The data suggest that application of well-being therapy may counteract loss of clinical effect during long-term antidepressant treatment.

Treatment of Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Well-being therapy has been applied for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder (Fava et al., 2005; Ruini & Fava, 2009). Twenty patients with DSM-IV GAD were randomly assigned to eight sessions of CBT or the sequential administration of four sessions of CBT followed by the other four sessions of WBT. Both treatments were associated with a significant reduction of anxiety. However, significant advantages of the WBT-CBT sequential combination over CBT were observed, both in terms of symptom reduction and psychological well-being improvement. These preliminary results suggest the feasibility and clinical advantages of adding WBT to the treatment of GAD. A possible explanation to these findings is that self-monitoring of episodes of well-being may lead to a more comprehensive identification of automatic thoughts than that entailed by the customary monitoring of episodes of distress in cognitive therapy (Ruini & Fava, 2009).

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder

The use of WBT for the treatment of traumatized patients has not yet been tested in controlled investigations. However, two cases were reported (Belaise, Fava, & Marks, 2005) in which patients improved with WBT, even though their central trauma was discussed only in the initial history-taking session. The findings from these two cases should, of course, be interpreted with caution (the patients may have remitted spontaneously), but are of interest because they indicate an alternative route to overcoming trauma and developing resilience and warrant further investigation (Fava & Tomba, 2009).

Cyclothymic Disorder

Well-being therapy was recently applied (Fava et al., 2011) in sequential combination with CBT for the treatment of cyclothymic disorder, which involves mild or moderate fluctuations of mood, thought, and behavior without meeting formal diagnostic criteria for either major depressive disorder or mania (Baldessarini, Vazquez, & Tondo, 2011). Sixty-two patients with DSM-IV cyclothymic disorder were randomly assigned to CBT/WBT (n=31) or clinical management (CM) (n=31). An independent blind evaluator assessed the patients before treatment, after therapy, and at 1- and 2-year follow-ups. At post treatment, significant differences were found in all outcome measures, with greater improvements after treatment in the CBT/WBT group compared to the CM group. Therapeutic gains were maintained at 1- and 2-year follow-ups. The results of this investigation suggest that a sequential combination of CBT and WBT, which addresses both polarities of mood swings and comorbid anxiety, was found to yield significant and persistent benefits in cyclothymic disorder.

Are Psychotherapy-Induced Modifications in Well-being Enduring?

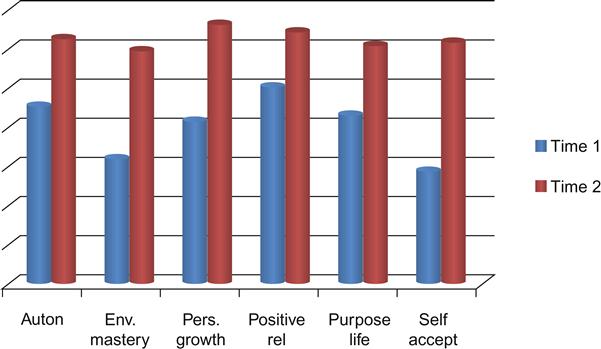

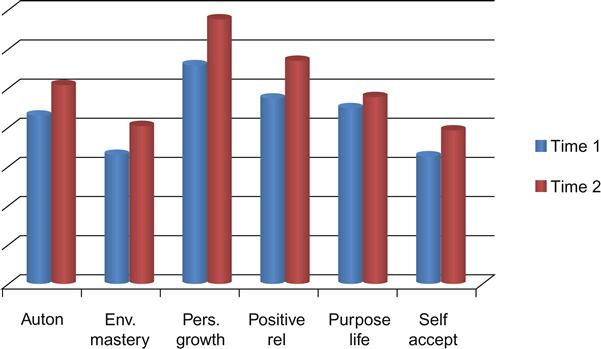

Well-being therapy’s effectiveness may be based on two distinct yet ostensibly related clinical phenomena. The first has to do with the fact that an increase in psychological well-being may have a protective effect in terms of vulnerability to chronic and acute life stresses. The second has to do with the complex balance of positive and negative affects. There is extensive research—reviewed in detail elsewhere (Rafanelli et al., 2000; Ruini et al., 2003)—that indicates a certain degree of inverse correlation between positive and negative affects. As a result, changes in well-being may induce a decrease in distress, and vice versa. In the acute phase of illness, removal of symptoms may yield the most substantial changes, but the reverse may be true in its residual phase. An increase in psychological well-being may decrease residual symptoms that direct strategies (whether cognitive behavioral or pharmacological) would be unlikely to affect. Figures 8.1 and 8.2 illustrate the changes in well-being that were entailed by WBT in two clinical studies (Fava et al., 1998a; Fava et al., 2005). Unfortunately, measurements of psychological well-being at follow-up were not available; yet, the stability of clinical gains that was reported may suggest a similar endurance.

Auton=Autonomy; Env. mastery=Environmental Mastery; Pers. growth=Personal Growth; Positive rel=Positive Relations with Others; Purpose life=Purpose in Life; Self accept=Self-Acceptance. (Source: Fava et al., 2005).

Auton=Autonomy; Env. mastery=Environmental Mastery; Pers. growth=Personal Growth; Positive rel=Positive Relations with Others; Purpose Life=Purpose in life; Self accept=Self-Acceptance. (Source: Fava et al., 1998a).

Cloninger (2006) attributes the clinical changes related to well-being therapy to three character traits defined as self-directedness (i.e., responsible, purposeful, and resourceful), cooperativeness (i.e., tolerant, helpful, compassionate), and self-transcendence (i.e., intuitive, judicious, spiritual). High scores in all these character traits have frequent positive emotions (i.e., happy, joyful, satisfied, optimistic) and infrequent negative emotions (i.e., anxious, sad, angry, pessimistic). The lack of development in any one of the three factors leaves a person vulnerable to the emergence of conflicts that can lead to anxiety and depression (Cloninger, 2006). These character traits can be exercised and developed by interventions that encourage a sense of hope and mastery for self-directedness. Indeed, in a study performed in the general population (Ruini et al., 2003), several PWB scales displayed significant correlations with Cloninger’s Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire (Cloninger, 1987).

Further, it has been suggested that cognitive behavioral psychotherapy may work at the molecular level to alter stress-related gene expression and protein synthesis or influence mechanisms implicated in learning and memory acquisition in neuronal structures (Charney, 2004). Research on the neurobiological correlates of resilience has disclosed how different neural circuits (reward, fear conditioning and extinction, social behavior) may involve the same brain structures, and particularly the amygdala, the nucleus accumbens, and the medial prefrontal cortex (Charney, 2004). Singer, Friedman, Seeman, Fava, and Ryff (2005), on the basis of preclinical evidence, suggested that WBT may stimulate dendrite networks in the hippocampus and induce spine retraction in the basolateral amygdala (a site of storage for memories of fearful or stressful experiences), leading to a weakening of distress and traumatic memories. The pathophysiological substrates of well-being therapy may thus be different compared to symptom-oriented cognitive behavioral strategies, to the same extent that well-being and distress are not merely opposites (Rafanelli et al., 2000).

Conclusions

The controlled trials of well-being therapy that we have discussed indicate that psychological well-being may be increased by specific psychotherapeutic methods and that these changes are closely related to decrease in distress and improvement in contentment, friendliness, relaxation, and physical well-being. Unlike nonspecific interventions aimed at increasing control or social activity that yield short-lived improvement in subjective well-being (Okun, Olding, & Cohn, 1990), changes induced by WBT tend to persist at follow-up (Fava et al., 2002; Fava et al., 2004; Fava et al., 2005; Fava et al., 2011), underlie increased resilience, and entail less relapse in the face of current events.

WBT was originally developed as a strategy for promoting psychological well-being that was still impaired after standard pharmacological or psychotherapeutic treatments in clinical populations. It was based on the assumption that these impairments may vary from one illness to another, from patient to patient, and even from one episode to another of the same illness in the same patient. These impairments represent a vulnerability factor for adversities and relapses (Fava & Tomba, 2009; Ryff & Singer, 1996; Wood & Joseph, 2010). WBT, thus, can be considered a therapeutic positive intervention developed in clinical psychology, which takes into consideration both well-being and distress in predicting patients’ clinical outcomes (Rafanelli & Ruini, 2012). Further, we suggest that the pathway to optimal, balanced well-being can be obtained with highly individualized strategies. In some cases, some psychological dimensions need reinforcement and growth. In other cases, excessive or distorted levels of certain dimensions need to be adjusted because they may become dysfunctional and impede flourishing. Individuals may be helped to move up from impaired low levels to optimal, but also to move down from inappropriately high to optimal-balanced levels. This could be achieved using specific behavioral homework, assignment of pleasurable activities, but also cognitive restructuring aimed at reaching a more balanced positive functioning in these dimensions. Unlike standard cognitive therapy, which is based on rigid specific assumptions (e.g., the cognitive triad in depression), WBT is characterized by flexibility (Kashdan & Rottenberg, 2010) and by an individualized approach for addressing psychological issues that other therapies have left unexplored, such as the promotion of eudaimonic well-being and optimal human functioning. The diverse feasibility and flexibility of WBT are in line with the positive clinical psychology approach, which calls for a number of different interventions to be selected based on individual specific needs (Wood & Tarrier, 2010).