The Wind in the Willows

Contrary to our expectations, the wind did not go down with the sun. It seemed to increase with the darkness, howling overhead and shaking the willows round us like straws. Curious sounds accompanied it sometimes, like the explosion of heavy guns, and it fell upon the water and the island in great flat blows of immense power. It made me think of the sounds a planet must make, could we only hear it, driving along through space.

ALGERNON BLACKWOOD, ‘The Willows’1

MY BACK takes a long time to heal. My daydream of finishing the journey by bicycle all the way to Donaueschingen has to be abandoned. All the men in my hospital ward have back injuries, and are in a much worse condition than I am. Three were in bike accidents, one fell off a ladder. Each day we hear the helicopter, bringing spinal injury cases from all over the country. Every evening the nurses bring our painkillers. It's a Darwinist democracy – the most able man in each ward gets to hobble out, and plead with the nurses on behalf of a fellow-victim. The best and worst moment each day is the ‘big visit’, when the top doctors and their acolytes tour the wards. They alone have the information which we, the patients, need: the latest analysis of our condition, the experts' opinion on our future lives.

On the third day ‘the white-haired one’ as the nurses have dubbed him, as his name is unpronounceable, appears beaming at my bedside. ‘Where's the American?’ I hear him say – and hope he is better at biology than geography. ‘Good news!’ he booms. The crack in my vertebra could be better described as a fracture. It will probably heal completely in three months. I can go home that evening! I feel hot tears of gratitude, of laughter, rolling down my cheeks.

The winter is a long one. Three months turn into six months. I can walk, stand, even sit a little, but not very much. I cannot run, or cycle, or play football with my youngest sons. Early each morning I travel one stop on the tram with the boys, to set them on their way to school. Other men wave at trains. I alone wave at trams, until the number 41 or number 19 to Batthyány Square turns the bend, out of sight.

Count Lajos Batthyány was Hungary's first prime minister, in office for less than two hundred days, and was executed by the Austrians for his part in the failed revolution of 1848.2 He was born by the Danube, in Bratislava or, as the Hungarians have always known it, Pozsony, in 1807. One of his less well-known achievements was to plant fifty thousand mulberry trees on the estate of his manor house in Ikervár by the Rába river, a tributary of the Danube in western Hungary.3 The plan, hatched with fellow reformers such as István Széchenyi and Lajos Kossuth, was to build up a Hungarian silk industry. The trees still flourish in the grounds. For much of the twentieth century the house functioned as a children's home and the fruit was a consolation for orphans.

Once my children are safely on their way to school, I walk along the Danube shore. Freedom Bridge crosses to Pest at this point. I walk down one stairway, cross a busy road, then climb another set of steep steps down to the water. In late January, as temperatures brush minus 20 Celsius, a procession of ice-floes appears in the waters, messengers from upriver. The level of the water is low, so I can walk along the narrow shore in the early morning gloom. I am rarely completely alone. A man called László in his early seventies discharged himself from hospital with a life-threatening condition. He comes and sits by the river to fish. Either the river will heal him or the cold will finish him off, but he's not going back to that hospital, he says. Another man, Imre, in a rather expensive overcoat and good shoes, who carries his possessions in two large plastic bags, has been homeless for ten years since he returned from teaching in Cairo. He has a long-running court case against the person who occupied his flat while he was away, and although he could rent another place, this would lessen the pressure on the court to rule in his favour. I don't know how much of his story is true. I see him for several days in a row, eating his breakfast in a little park opposite the Gellért Hotel. His mind wanders as we speak, between the articles he reads voraciously in discarded newspapers, his memories of Egypt and Greece, his sense of injustice, and knowledge culled from a lifetime of reading and thinking. Our last conversation is about British princesses. Then he disappears.

There is a place where waste water from the thermal springs beneath the Gellért Hotel flows out into the Danube. In the snow and ice, this becomes a favourite haunt of ducks, coots and seagulls. The seagulls fly to and fro through the rising steam, relishing the damp heat on their wings, then settle on the rocks close by. The ducks bathe and flutter importantly in the warm waters, like pashas in a Turkish bath. The colder the morning, the bigger the crowd of birds. They are nervous of my presence, but grow used to it after a while, the stranger with the walking stick, and a black box which clicks but does not flash. When the river is high, the steam outflow disappears beneath the swollen waters. Unable to go far, I get to know the river in one place, day after day. I notice how swiftly the level changes, in a matter of days or even in hours. I witness the constant changing of its colour, of its surface, and the skyline along the Pest bank, the churches and water towers, the strange whale-like structure over the old warehouses and marketplace, and I explore the half kilometre between the Danube and my home off Béla Bartok Street, and the people who frequent it. There is the young street-sweeper with a pony-tail, pushing a giant pram loaded with leaves, beer cans and old newspapers. After Christmas he plants a sprig of evergreen in the front left corner of his cart, his very own Christmas tree, bristling like his moustache. There are the women in the bakery that sells four different kinds of rye bread, and buttery French croissants if I am not there too early. Hungary is a nation of the kifli, a crescent-shaped white bread roll presumably inspired by the crescent moon on the mosques during the Turkish occupation. This particular bakery also boasts a long, straight salty ‘beer’ kifli – presumably to prove a Hungarian genius for taking the best from Ottoman times and bending it to their will. Just outside the bakery there is always a big man in a suit that fits awkwardly beneath his big anorak, with a small moustache perched like a cockroach on his upper lip, of which he seems inordinately proud. His black shoes are polished to a high gloss, and, like the street sweeper, there is always a cigarette in his left hand. While more fortunate peoples turn their backs on this ugly habit, the Hungarians still love their cigarettes. They wear them on their hands like medals from lost wars.

Closer to Mészöly Street, I encounter the dog-walkers. Little clusters of smiley women with small, yapping dogs who walk over Gellért Hill at first light, and congregate on the street for a good chat while their dogs sniff each other. We greet one another warmly, with a nod or a grin, but never once stopping to go beyond appearances.

One morning in January, the children and I make a miniature snowman on top of the green litter bin at the tram stop from three small snowballs. The end result bears an uncanny resemblance to the Venus of Willendorf.4 The rim of his cap is a gleaming Hungarian five forint piece. When I come back, twenty minutes later, he has already gone – stolen for his cheap cap, knocked down by some fun-hating fellow perhaps, or taken carefully away and set up again on some glorious windowsill.

Twelve warm springs flow beneath Gellért Hill.5 In the Ottoman era this was known as Gerz Elias Hill, after a Bosnian hero, killed when he paused to pray in the midst of battle. The Turks called the springs the atchik ilidja – the ‘bath of the virgins’, and built a structure over it to keep the virgins suitably discreet and entertained during their ablutions.6 This was destroyed during the Austrian siege in 1686, and rebuilt piece by piece over the following centuries. When the dust had settled, the virgins returned, if we can believe the canvases of those fortunate nineteenth-century artists allowed in to paint them. The Hungarians more prosaically called it ‘the muddy baths’.

In the 1920s and 1930s, the hotel above grew ever more magnificent, with porcelain tiles from the Zsolnay workshop around the baths and scenes from János Arany's ‘Death of Prince Buda’ up the main stairs of the hotel.7 The sixth canto of the poem tells the story of a hunting expedition by Hunor and Magyar, which begins on the shore of the Caspian Sea in pursuit of a miraculous stag. It ends on the shore of the Sea of Azov, where the two heroes settle on an island and carry off two local maidens. Their offspring become the founders of the Huns and the Magyars. The closed area of the baths lies beneath the main road leading to Freedom Bridge. Stairs lead down off a long damp corridor to an octagonal pool where the warm water disappears into the rocks. Invisible trams rumble overhead. The temperature is 30 degrees Celsius, but the humidity is close to 100 per cent. I climb a ladder into an overhanging cave to see the source of one of the springs, hewn deep in the reddish-grey rock.

Thermal waters are Hungary's hidden treasure. The earth's crust is thinner here, so the waters are closer to the surface than in most countries. The baths are famed for their healing powers, and for the sheer pleasure of immersing your body in them. They are situated in a gradual curve, starting at Gellért Hill, curling north-west from Buda through the Pilis Hills and finally to Hévíz – which means ‘warm water’ – 160 kilometres from Budapest. The warm waters must have been a decisive factor in encouraging first the Celts, then the Romans, then the Hungarian tribes to stay here, and no doubt made the Turks reluctant to go home as well.

In the early 1990s I began to research the fate of the springs of Budapest, alarmed by newspaper reports that suggested the water levels were falling dramatically. The opening of one new bath after another, especially on the Pest side of the river, the bottling of more and more spring water to be sold as mineral water, and the wastefulness of the bauxite and coal mines in Tatabánya, which poured first class water down the drain, day and night, all took their toll. If the thermal waters fall below a certain level in Budapest, the Danube will flow in and destroy them. From 1965 to 1975 alone, 292 thermal wells were drilled in Hungary. ‘We are on a knife-edge,’ István Sárvári of the Water Resources Research Centre told me, ‘and you cannot live on a knife-edge for long.’8 A team led by him drew up a plan to save the waters. The mines, thermal baths and mineral water bottlers were asked to limit their consumption. Swimming pools were told to clean and reuse their water, and leave the healing waters for the special establishments. The plan was largely followed. By 2012 there were two dozen bathing houses and thirty-six specialised baths in the Hungarian capital, tapping 118 thermal springs and consuming seventy million cubic metres of water a day. As far as I could find out, the danger has passed – for now. To put the numbers in perspective, the Danube flows through Budapest at an average rate of two thousand cubic metres a second. In the whole country there are close to 1,300 thermal baths.

During the late 1980s and early 1990s, Mihály Dresch and his Jazz Quartet played nearly every Friday in Kinizsi Street, on the far side of the Danube from where I live. The venue was a spacious, rather dingy, students' bar, improved by the candles on each table, cheap beer, the haze of cigarette smoke, but above all by the music. Mihály Dresch himself, a tall willow of a saxophone player, silent as a bass player, could make a twig sound melodious.9 Over the years we move cautiously from a smile of recognition to brief exchanges of greetings. He rarely sings at his concerts, too busy with his flutes and clarinets and saxophones, but when he does his voice is haunting. My favourite is his rendition of a Transylvanian love song:

Maros partján elaludtam, jaj de szomorút álmodtam

Azt álmodtam azt az egyet hogy a babám mást is szeret.

Szeress, szeress csak nézd akit,

Mert a szerelem megvakit …

I fell asleep on the banks of the Maros, and there I had the saddest dream,

I dreamt my darling has another lover besides me.

Love then, love, but watch out who,

Because love can blind you, love can blind you …

The Maros, or Mures river in Romanian, flows for 760 kilometres through Romania, to finally reach the Tisza in Hungary at Szeged, which in turn flows into the Danube near Slankomen. That's a lot of shoreline, to walk with one's sweetheart, and fall asleep and dream the sweetest as well as the most bitter dreams.

Another version of the same song has a man fall asleep beside the Tisza, not the Maros. He dreams the saddest dream, that ‘I will never be yours, my darling’. He wakes to see nine gendarmes standing over him. ‘Where are your papers?’ they ask. ‘I'll show you my papers,’ he says, and pulls out a pistol from the inner pocket of his jacket, and shoots down two or three of them. ‘Oh God, what shall I do now? Should I flee or should I stay?’

In my wardrobe at home I have a bright blue T-shirt, embroidered with both the Turkish crescent and Hungarian tricolour, a gift from the President of Turkey Sultan Demirel when he visited Budapest in 1997. The year is embossed on the shirt, just beneath the flags, with the name Gül Baba. The shirt is so well made, it looks as good as new sixteen years later. Gül means rose in Turkish, and Gül Baba is the father of the roses, just as Babadag in Romania near the start of my journey was the mountain of the father. Gül Baba was a Bektashi monk who arrived in Buda after the battle of Mohács in 1526, already advanced in years.10 He died in 1541 during the first Friday prayers to celebrate the Ottoman occupation of the city by Suleiman the Magnificent, in what is now Saint Mátyás church. Janissaries were soldiers of the Ottoman armies, abducted by Turkish press-gangs from Christian families in their youth, then trained as soldiers or administrators of the Ottoman empire. Many were Bektashis.11 It is the only one of the mystic Sufi orders that permits the consumption of wine – for religious purposes. This clearly endeared them to the wine-loving Hungarians, as did Gül Baba's work on the ground. He established a soup kitchen for the poor on what has been named Rose Hill ever since, in his honour.

An octagonal tomb or türbe was erected over his grave by the Turks. This was one of the few Ottoman buildings which the Hungarians and Austrians did not demolish after the Turks were expelled in 1686. For a brief period in the eighteenth century it was converted into a Christian chapel dedicated to Saint Joseph, but since then the tomb's Muslim character has been respected by the Hungarians. In the mid-1990s it was carefully restored with Turkish state funds. A rather fanciful bronze statue of Gül Baba now stands at the start of a little promontory, with an excellent view along the Danube. There is a rose garden, with roses brought from Turkey as well as local, Hungarian varieties, a fountain and an art gallery. Outside the site, old horse chestnut trees bow their heads over the tomb. Inside, the coffin is draped in emerald green embossed with gold, and the Bektashi mitre, the symbolic turban of the sheikh, stands at the raised end. It is the quietest and one of the most beautiful places in the whole city. It is also the northernmost place of Islamic pilgrimage in the world. On the eve of the First World War, in an early flurry of Hungarian–Turkish friendship, a joint commission of archaeologists excavated the tomb.12 Beneath the floor they found the skeleton of an elderly man, corresponding in stature and date to the sparse descriptions of Gül Baba, as well as the remains of two other men, one a soldier, killed in battle, probably during the siege in 1686. My 1907 edition of Béla Tóth's Gül Baba portrays a white-turbaned, white-bearded fellow on the cover, leaning on a walking stick, surrounded by pink roses. ‘The scent has long gone …’ the tale concludes, ‘the grandchildren have died, but the memory of the good Gül Baba lives on, a saint even if he performed no miracles, a poet even if he wrote no verses, and a man who loved roses, even if he sometimes wasted a few.’13

In March 2010 I took an underground train to the docks at Újpest to board the Tatabánya, a handsome riverboat, built at Balatonfüred on the shore of Lake Balaton fifty years earlier. Forty-nine metres long and seven metres wide at her broadest point, she had a 1,200 horsepower diesel engine, and could reach twenty kilometres per hour in quiet waters. Boat enthusiasts devoted their free time for several years to lovingly restoring her. The month before my journey, she was involved in the rescue of two German registered barges, the Würzburg and the Bavaria 53, which struck an infamous ledge of rocks on the riverbed near Dömös, in unseasonably low water on the Danube. On that March day her crew were commissioned to deliver the shell of a floating restaurant to a customer beyond Esztergom, about six hours steady haul upstream from Budapest. There's a crew of five, including Gábor Jáki, president of the Hungarian Shipping Association, and László Vasanics, the captain. The cold of the March morning soon evaporates on the bridge, as we head out under the railway bridge and leave the noise of the city far behind. The sun comes out and the water is as clear as a mirror, reflecting perfect cumulus clouds. The wheel of the Tatabánya is enormous, and the ship only responds to a strong spin in one direction or the other. All the crew sail for the pleasure of it now – most are ex-employees of the state shipping company Mahart.

‘In communist times,’ one of the older crew tells me, ‘the best thing about working for Mahart was the smuggling.’ Travelling once a month up the Danube to Regensburg in Germany, the crew would hide caviar and champagne behind the panels on the journey upriver, and fill the same cavities with French perfumes and jeans – unavailable in the eastern bloc – on the way back. In 2004 Mahart was privatised and lost all its river-going goods ships, though it continues as Mahart Passnave with some passenger traffic. The privatisation was the final blow in a long decline in the fortunes of Hungarian river transport since the glory days of the late nineteenth century when Orşova was still a Hungarian port, and when Hungarian ships dominated the middle and lower sections of the river. The rot began when Hungary lost the First World War on the German side, and lost not only two thirds of its territory but had to pay reparations. These included the pride of the Hungarian river fleet. This was painstakingly rebuilt in the 1920s and 1930s, only to be decimated again in the last years of the Second World War, sunk by Russian air raids and mines laid in the river, during the terrible four-month siege of Budapest in the winter of 1944. The fleet was restored under the communists, and between 1945 and 1995, ‘three million passengers and two million tonnes of cargo a year were transported on the Danube,’ the Mahart website proclaims proudly.14

In 2004 the Hungarian cargo fleet was bought by the Austrian Danube Steamship Company DDSG. Then it was sold to the Swiss firm Ferrexpo in 2010, which ships iron ore pellets on the Danube. The pellets are produced at the company's vast open-cast mines in central Ukraine, on the left bank of the Dnieper river. The iron, which feeds the steel plants of Europe, is quarried from beneath lands which once fed one of Europe's first civilisations: the Tripol'ye-Cucuteni.15

The engine room of the Tatabánya is an orchestra of grey-, green- and red-painted pumps and pistons. It is also the warmest place on the boat. The paint is peeling, however, and the ship is losing money, and may have to be sold. The sun disappears behind the clouds. We pass Vác, with its famous prison right on the shore of the river. This was once home to the Hungarian train bomber Szilveszter Matuska, who escaped in the chaos after the Second World War and was never seen again.16 The Danube is silver now, painted with black and white clouds. We pass Szentendre, a pretty town of yellow churches, where Serbs fleeing the Turks took refuge. In 1720 nearly 90 per cent of the population were south Slavs. We take advantage of the high Danube, leave Szentendre Island to starboard, and come out on to the wide Danube bend at Visegrád. The sandbanks on the northern tip of the island are invisible beneath the swirling waters. When the river is low, this has always been a favourite place to bring my children, to build fires from driftwood, caught high and dry in the tall willows on the shore.

Opposite Visegrád, on the left bank of the Danube, is Nagymaros, where the final section of the Gabčikovo-Nagymaros hydroelectric project was nearly constructed.17 The avant-garde jazz pianist György Szabados brought his grand piano down on to the shore of the river, to play against the dam. The Danube Circle, led by the biologist János Vargha, was formed to oppose it. When I came to Hungary in the mid 1980s, my first reports were about the Danube Circle. At that time you could be arrested or beaten up by police for even wearing their badge – a winding blue line, split by white. Austrian Parliamentary deputies came to Budapest in 1986 to help the campaign, and were detained in Batthyány Square at the entrance to the metro. When I tried to take photographs of the arrest, I was detained with them. We spent three hours locked in a classroom as embarrassed policemen and their political masters tried to decide what to do with us. Eventually we were released with a warning. Illegal demonstrations up to twenty thousand strong marched on parliament to demand that the project be scrapped. The first democratically elected government, under József Antall, unilaterally cancelled construction. The Slovaks pushed on regardless, and twenty years later, the two countries are still arguing over the division of the waters. László Vasanics explains why the question of the Nagymaros dam is still a painful one for Hungary. The site at Nagymaros is the only place it could have been built, he explains, because of a cliff beneath the waters close to the village of Dömös, a few kilometres upstream from Visegrád, and because of the Szentendre Island which we have just passed. Also, it happens to be one of the most beautiful places in the whole country, since the loss of the mountains of Upper Hungary (Slovakia) and of Transylvania, to Romania, after the First World War. The Pilis mountains on our left, and the Börzsöny mountains on the right, hide their heads behind hands of low cloud.

Then we pass Helemba Island, 1,713 kilometres from the lighthouse at Sulina and the mouth of the Vah river on the Slovak bank. The island, like most islands, was a burial ground before the Magyars occupied Hungary. First mentioned in church records in the thirteenth century, it became famous for its apricot trees. Now it is uninhabited, a great bush of willows, just turning green. Grey heron watch our ship pass, feigning interest in anything other than the wash of our bow wave on their gravel bank. Travelling the other way the Dutch-registered Novalis from St Annaland sweeps downriver. We pass under the green Mária Valéria Bridge that links Esztergom, the seat of the Hungarian Roman Catholic Church, to Štúrovo on the Slovak bank. This was destroyed in the Second World War, and its ruins stood for decades as a denial of the official myth of Hungarian–Slovak reconciliation, under the careful control of socialist internationalism. It was finally rebuilt in 2001, and has since been much prized by Slovaks as a way to get to work in Hungary, where unemployment is much lower, and for Hungarians to stroll over to the thermal baths in a town they still call by its pre-war name, Párkány, and taste some proper beer.

We deliver the boatel to its owners in a small bay overhung with willows. There are strange huts, poised above the water on sturdy concrete bases, on a superstructure of steel. The new restaurant looks small once we have cast her off, the red hull and bright white upper decks shrink into the shore. In the distance stand the blocks of flats on the outskirts of Esztergom.

This was one of the last trips of the Tatabánya. Burdened by the cost of her upkeep, her owners reluctantly sold her to a Greek shipping company soon after my journey. Renamed the Anya, and sailing under the convenience flag of Panama, she motored away down the Danube, bound for Istanbul in September 2010. It has never been particularly lucky to rename boats, and this was no exception. On 5 December 2010 the Anya foundered in heavy seas with the two barges she was pushing, just off the Black Sea beach of Kilyos, north of Istanbul. One of the barges broke in two and sank. Listing heavily and taking on water, the Bangladeshi crew managed to steer the Anya and the other barge onto the sandy beach of a popular holiday resort. Nothing more is known of her. Her former Hungarian fans believe she was taken to the scrapyard.18

In July 2012 I visited Szentendre again to meet the Slovene geomancer Marko Pogačnik. Originally an avant-garde artist and sculptor, he became an adept at the ancient art of geomancy – divining from the earth – and developed what he calls lithopuncture.19 Tall, carved stones are placed carefully at strategic places on the crust of the earth, to heal the damage done by human violence. One area of conflict where he has placed stones in the past is either side of the border between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

Pogačnik's own country took him seriously enough to choose his design for a new coat of arms for Slovenia, newly independent of Yugoslavia. Like the old coat of arms, the centrepiece is the triple-peaked Mount Triglav, Slovenia's sacred mountain. New features include a two-lined river running across its base, instead of the old three-lined river, and an inverted triangle of silver stars representing democracy poised on a dark blue sky above the mountain. It is a fine symbol, even a powerful one, and Slovenia has prospered under its blessing since independence more than most countries in eastern Europe.

We sit drinking late harvested white wine from Balatonakali in a friend's garden. He has just finished a three-day course of lectures, teaching people to read and communicate with nature, with trees in particular. The earth, he believes, is going through a massive transformation and needs our cooperation to succeed. If we refuse, or fail to do what is needed of us, he fears the end result will be chaos.

In Lotti and Kata's garden in Szentendre I wanted to talk to him about the Danube. Especially about the harm done to it by human intervention, the vast regulation works of the past hundred and fifty years, the straitjacket into which the river is forced, the dams and dykes. For all its lingering beauty, at dawn or sunset, what happens to a river when people treat it as a motorway for ships, or a flush toilet to take away their waste? ‘Ecologists, as people with rational minds, always look in a segmented way at a central point, while for me what is important is this aspect of the river that is whole in every place. This means that if a river has enough space and time to enjoy its young days, and places in-between to regenerate, then the river is capable of overcoming these problems … There is a limit, nevertheless, to how much a river can take. So this is not an excuse for what humans do. It is optimistic, but it is also demanding, to be more conscious …’

A lot of Marko's recent work has been in cities. In Paris, he had a vision of the Seine holding a plate up out of the waters, with a snake curled up on it, representing the whole course of the river. ‘We think of relationships being always between human beings, but the river is also somebody, is a being, is an individual, is somebody in our vicinity. It is not enough just to enjoy a walk along the river. There should also be at least two minutes dedicated to the river – diving with one's sensitivity, so to say, into the river. Feeling it, sending an impulse from the heart. If we could learn again to relate to rivers – this would be a great help to these beings … I was working east of Basel, at Rheinfelden. There is a big plan by the German and Swiss governments to make a gigantic dam on the Rhine. And while I was working there I had a vision that the Rhine showed itself as a dry channel, completely dry, and the snake was not coiled but in knots. It was a sense of the great alarm of the river. The Rhine was making me aware of what problems the river would have to overcome such an obstacle – to stay one, to stay interconnected.’

He tells me one story of the Danube in Budapest. ‘When I was trying to sense the presence of the river, I was very surprised that at the Gellért – which is like a natural dam – the river starts to flow backwards. Not physically, but as if the essence of the river would turn back to the height of Margit Island, and, let us say, circling and spiralling this whole area. It is as though something important is taking place in its history, like an initiation. As though it is gathering its energy before this great outflow into the Hungarian plain.’

Upstream from the city of Győr, the Szigetköz and Csallóköz (Žitný Ostrov) region of the Danube between Hungary and Slovakia spreads like a fan of islands, of floods and shallows, and was once the main breeding ground of the sturgeon and all the sixty or so fish species in the river. When Algernon Blackwood wrote about it, at the start of the twentieth century, this stretch was still largely intact, a mysterious and often frightening stretch of river, where the spirit of the Danube turned suddenly serious, haunting and awe-inspiring.

The 1977 state contract between Czechoslovakia and Hungary foresaw a massive intervention along a two hundred-kilometre section of the river, from the Danube bend at Nagymaros to the uppermost tip of the new storage lake in Slovakia. The stated aims were to win 880 Megawatts from the river, to eradicate flooding and improve navigation. The end result, according to the preamble of the treaty, ‘will further strengthen the fraternal relations of the two States and significantly contribute to bringing about the socialist integration …’20 Instead, the project has poisoned relations between the two countries, destroyed precious wetland forests, and threatened the long-term water supply of millions of people. The only mention of the environmental impact in the original treaty was Article 19. ‘The Contracting Parties shall, through the means specified in the joint contractual plan, ensure compliance with the obligations for the protection of nature arising in connection with the construction and operation of the System of Locks’.21

On the positive side, the Gabčikovo dam provides 8 per cent of Slovakia's electricity supply, according to official estimates, and a large water-sports facility on the storage lake near Čunovo.

The centrepiece of the project was the diversion of the waters of the Danube into a vast above-ground canal, thirty kilometres long inside Slovakia, to generate electricity at Gabčikovo. Another dam was to be built, 120 kilometres downstream at Nagymaros in Hungary, to generate more power and to limit fluctuations in the water level. The plan was for the two countries to build the scheme together and share the electricity. Even some of the tame government scientists who studied the project were appalled by the implications. They feared the impact on the immediate area, on the vast underwater aquifer that had taken tens of thousands of years to build up, filtered through the gravel and washed down from the Alps. They worried about the impact on the flora and fauna on the banks of the Danube, both in the areas of construction, in those covered by the sixty-square kilometre storage lake and along the section of the river between the two power stations. When the Hungarian radio journalist János Betlen put some of these questions to a senior Hungarian engineer in 1983, the answers were so weak that he was ordered to go back and do the interview again, this time with carefully vetted, soft questions and reassuring answers. He suggested they send a technician instead, not a journalist, if they already knew the answers they wanted. He was suspended for six months.22

The protests on the Hungarian side that stopped the Nagymaros dam in the early 1990s were hardly mirrored on the Slovak side. Work was almost 80 per cent completed in Slovakia when communism collapsed and Slovakia was building up to independence from the Czechs on 1 January 1993. Instead of recognising it as a white elephant, the dam at Gabčikovo, and all the canal and construction projects which went with it, became a prestige project for the nationalist prime minister Vladimir Mečiar. The fact that most of the inhabitants of the area affected were ethnic Hungarians made it even more painful for Hungarians – and sweeter for the Slovak government. Just as for the Romanian and Serbian governments when the island of Ada Kaleh was destroyed by the Iron Gates dam, the local inhabitants were seen as collateral damage. When Hungary washed its hands of the project, Slovak engineers put an alternative version, the ‘C-variant’, into operation. In October 1992 they diverted the Danube a few kilometres further upstream than originally planned, at Čunovo rather than at Dunakiliti. There, both banks of the river are on Slovak soil, and the Hungarians were powerless to stop them – except by military force, which was never contemplated. In a matter of days, the great bed of the Danube, or rather the labyrinth of beds through which it flowed, on both the Hungarian and the Slovak side, dried up. Algernon Blackwood's wilderness, where rebels once lured unsuspecting conquerors to their doom, was drained. I spent the last six months before the diversion filming in the forests and creeks, and in the villages on both sides of the river. The people were bitter, but resigned to what was about to happen. ‘Our throat will be cut,’ said Ferenc Tamás, a fisherman on the Hungarian side.23

On the Slovak side of the Danube at Csallóközaranyos, Ferenc Zsemlovics took us down to the huge gravel beach where he used to wash gold with his father, and set up his apparatus one more time. A watery sun rose over the willows as he poured gravel through a wooden contraption that looked like a raised hen hatch, turning every grain, not just the gold flakes, to burnished gold. Ferenc's father bought his first car with the little ingot of gold he and his son washed from the river. They took it into the bank, exchanged it for cash, and took the money straight to the Skoda salesroom, sometime in the mid 1970s. There was so much gold in the Danube then, if you knew where and how to pan for it, Ferenc said, even his village was named after the metal: Arany in Hungarian means gold. When the people weren't washing gold from the river, they were fishing. He remembers from his childhood that a Jewish merchant called Mr Weiss used to buy their fish from them, and take it on his horse and cart to the market in Bratislava. His father was also taught to wash gold by an elderly Jew in the village. Almost all the eighty thousand Jews of Slovakia were killed in the Holocaust.

Béla Marcell arrived from the museum he directed in Dunajská Streda, Dunaszerdahely, to be interviewed on the banks of the river just before it was diverted. He was well -versed in the rich folk stories of the region. ‘Among the people of Csallóköz there are many legends about supernatural beings, about the storm wizard, whom people think of as a student. With his eleven companions, he studied the art of storm-bringing in a cave. And when he had completed his studies he set out to visit the villages in a ragged gown. When he arrived in a village, he always asked for something to eat and drink. Whatever he was offered had to be whole – a whole loaf of bread, from which he cut himself a slice, or a whole jug of water from which he poured himself a drink. And when he was given what he had asked for, he blessed that village, and the next harvest was always good. But when he did not receive what he'd asked for, he cursed it, and storm or fire followed his visit, blowing away the roofs or destroying the crops. That was his punishment.24 … The storm wizard is said to have had a book from which only he could read. You or I might have studied it in vain, and have attended university, but we would never have understood a word. Now, once I was talking to a group of people in the village of Bős [Gabčikovo], and an old man piped up and said he knew where the wizard's book was – buried under an old tree on the Danube shore. So I suggested to him that we should go together, at midnight, and dig it up. “Are you mad?” he retorted. “We would be torn apart by the witches …” So we couldn't dig the book out. And it seems to have been buried beneath that monster’ – he emphasised the last word with venom, and nodded his head towards the hydroelectric dam – ‘which has made the whole place so hideous.’

Twenty years later, in the spring of 2012, I return to see the hydroelectric turbines, the canal, the storage lake, and meet some of those I interviewed in 1992. Béla Marcell had died two years earlier, but in Csallóköznádasd I meet Elenóra, the daughter of Sándor Bölcs. Sándor was a self-taught thatcher who thatched and repaired most of the houses in his village from the 1950s to the early 1990s. I remember him well, sitting astride his roof, speaking of his pride that he has handed his skill on to his sons and sons-in-law, so that they will still be thatching – he paused to grin, and point with his elbow, ‘when I am on the other side’. I followed his gaze, down the steep-sloping far side of the roof, and into the world of the dead. Elenóra is living in a more modern house now, built in front of the old thatched house where her father brought up the family. Just beyond it is the huge, outward sloping wall of the canal, eighteen metres high. If it were ever to break, hers is one of the first houses that would be swept away. Sándor crossed to the other side at the age of seventy, with prostate cancer, just a couple of years after I met him. ‘Even in the hospital in Bratislava, he was still making little models of the stall in Bethlehem – thatched of course,’ his daughter remembers. ‘It was certainly the hard work that got him,’ his son-in-law adds. ‘He would work in all weathers in the reeds, in the snow and cold and damp.’ He would stuff newspapers inside his rubber boots, and set out.

There's not much thatching done in the village any more – the roofs are tiled, and thatch is seen as a luxury. The four of them can still thatch, but only get to practise their craft three or four times a year, normally to repair a roof. They make a living from building and fencing now, instead.

To get to the three villages on the far side of the canal, Vojka, Doborgaz and Bodíky, a ferry crosses twice an hour, but is often stopped by high winds. There is almost always a strong wind now, they say, whereas before they were protected by the forests that were chopped down to make way for the dam and the canal. The villagers have been told that if the wind speed ever gets up to a hundred kilometres per hour, the dam could collapse.

The majority in the villages are now second-home owners. The dam and all the roads that were built with it completely opened up the closed world of villages and water, regular floods and islands, to the outside world. There are fewer and fewer Hungarians and more Slovaks, though the two peoples have always got on well, on a local, if not political, level. The storage lake beyond Čunovo, and all the other little recreation lakes into which the old wetlands have been channelled, are lined with weekend houses. Some of them are even thatched – ‘and some are really beautiful,’ Elenóra admits, readily. As we speak, she bounces her daughter Zsófi on her knee, and we sip red wine from the Izabella grapes Sándor planted in the garden. One thing that hasn't changed, they say, are the mosquitoes, barely a nuisance some summers, unbearable in others. Local people like to climb the walls of the canal, and watch the barges and passenger ships pass in summer. In winter, when the lakes freeze, the children skate as they always have, and Elenóra wishes her father had lived long enough to see his grandchildren skate. We bid each other fond farewells, and I drive down the road to Gabčikovo. On the top I park the car and watch the waves breaking along the huge mass of concrete and steel.

I drive towards Bratislava to see the ferry crossing, but crossings for the rest of the day have just been cancelled because the wind has reached sixteen kilometres an hour – and regulations say they should stop the ferry if it crosses the twelve kilometres an hour threshold. There are two ferries, but only one is in working condition. As well as the captain, several of the other crew gather round the table, to drink tea and chat about the old times. ‘What I miss most,’ says the captain, ‘is the kindergartens and schools. In Bodíky both have closed down, together with the post office. There's just a bar left – three bars in fact!’ The men laugh. A doctor visits the villages once a week: ‘you have to get ill on the right day!’ they laugh again. The villages have been connected to the mains water supply and to the sewage system. They drink water from the tap, not from the wells any more. And the soil is still good for their vegetables – for maize, wheat and sugarbeet.

I stop on the shore near Čunovo, to visit the Danubiana modern art gallery, on an exposed promontory.25 There are white waves on the grey green waters of the storage lake, and sculptures around the gallery, of strange blue, white and green figures, of rakish golf players, of a peculiar Napoleon head, by the Dutch-born sculptor Hans Van de Bovencamp, somehow add to the bleakness of the place on a cold day. ‘In creating large sculptures, he focuses on their interaction with the surrounding environment,’ reads the blurb. Two giant twisted metal hens or cockerels alone seem to do justice to the tortured former wilderness of the place. Out of the water huge piles of rocks protrude, and the lake is lined with concrete embankments.

At last, to my relief, a great V-shaped formation of geese flies high overhead, a reminder of the awesome symmetry of nature. I long for William Blake in this plastic playground.

In what distant deeps or skies

Burnt the fire of thine eyes?

On what wings dare he aspire?

What the hand dare seize the fire?26

The road into Bratislava from the Danube villages and Šamorín is quiet, compared to the brash motorways that approach the Slovak capital from other directions. I've chosen a boatel moored on the Danube bank to stay in, just beneath the white castle. One hundred and seventy-two kilometres of the Danube's length flow through Slovakia, and Bratislava, like Budapest and Belgrade, and to a lesser extent Vienna, owes much of its glory to the river.

Pulling my small suitcase down the plank, I'm assailed by a wonderful smell of Indian curry – there's an Indian restaurant on board. Over breakfast the next morning the manager tells me that the boat used to be busy as a floating brothel, downriver in Budapest, before he found a better use for it in Bratislava. He gives me a little brass cabin number from those times, number 301. I sleep like a log both nights on his sturdy craft, lulled into my dream world by river waves and seagulls.

Jaromír Šibl leans slightly forward over the table as we talk in his office, a tram's ride from the city centre, between the Botanical Gardens and the Waterworks Museum. He's a tall, bearded man with a Santa Claus twinkle in his eye, who looks as though he was born with a rucksack on his back. I first met him in the late 1980s and early 1990s, as he was one of the few brave Slovaks who opposed the construction of Gabčikovo. Now he runs an environmental organisation called Broz.27 ‘The main victim is nature. The point is that normally this was a floodplain area which was regularly flooded several times a year, the whole area, the islands, the meadows and the forests. You could only travel through the forest by boat. The whole ecosystem was based on this simple fact of regular floods.’ One pleasant surprise has been the lack of damage, so far at least, to the huge underground aquifer, beneath layers of gravel which are in places several hundred metres deep. There is a lack of research, he adds, but the research published so far by Slovak scientists is reassuring.

The fall in the ground water-level, on both sides of the river, but especially the Slovak side, is much more alarming. Hungarian engineers and policy-makers faced up to the fait accompli of the Slovak diversion of the river early on, he said. The only agreement ever reached between Hungary and Slovakia about the Danube was the construction of an underwater weir in the old bed of the Danube near Dunakiliti. This allows a small lake to build up from the remaining waters in the river, which is then carefully redistributed through the region via a system of natural and man-made streams and canals. This helps to keep the water level up, and prevents the complete drying out of the area which the diversion would otherwise have caused. On the Slovak side the situation is much worse, according to Jaromír, because the Slovak authorities refuse to do anything at all about the problem. ‘The official policy of Slovakia is that the 1977 treaty is still valid, and we should behave accordingly. This means that we should use whatever means we have to force the Hungarians to complete not only this part of the original project, but also to complete Nagymaros. So if we take any steps that were not envisaged in the original project, we would be implicitly agreeing that the Hungarians were right when they stepped out of the treaty. And this would weaken our position in an eventual future legal dispute. This is the main political problem which we have not overcome for the past twenty years.’

In 1997, the Court of Justice in Luxembourg found both countries guilty of breaking the 1977 treaty, Hungary for stepping out of it unilaterally and Slovakia for pressing ahead with the C-variant.28 It ordered both to reach agreement over the division of the Danube waters, of which Slovakia now takes 80 per cent. No agreement has been reached and none seems likely.

In Bratislava, the level of the Danube has risen half a metre as a result of the storage lake, adding to the flood threat during periods of high water. No studies have ever been published comparing the cost of construction and maintenance of the dams and managing the vast sediments in the storage lake with the value of electricity gained. Broz focuses its efforts on smaller projects, to improve or restore the natural balance of the river and the lands beside it: on Petržalka, the part of the city on the right bank of the river, dominated by vast housing estates, and on restoring traditional animal grazing on the banks near Bratislava and downstream at Komárno. Before the communists took over, the willow forests along the shore of the Slovak Danube were pruned by local people for firewood and grazed by their animals. After fifty years of neglect the Broz project enabled people to gather firewood again, and their animals drove back the many invasive species that had harmed the willows.

Before leaving Slovakia, I drive northwards to visit the castle and cliffs at Devin, overlooking the Danube. This is where the Carpathian Mountains start, and where the Old Europe of Marija Gimbutas ends – the westernmost point that the Copper Age civilisations reached. The castle stands on a steep cliff, overlooking the point where the Morava river flows into the Danube. The Romans dislodged the Celts from here, as from castle hill overlooking Bratislava. Devin is named after deva, the Slavic word for maiden. It was an important fortress on the corner of the Greater Moravian empire, as well as for the Hungarians. Following their defeat at the battle of Mohács in 1526, Hungarian kings were crowned in St Stephen's Church in Bratislava from 1536 onwards. In the mid-nineteenth century, the Slovak poet Lud'ovit Stur, after whom the town of Štúrovo, opposite Esztergom, is named, gathered his friends together to plot the birth of the Slovak nation, attracted by the rugged beauty and historic importance of the place. That was only forty years after Napoleon's retreating forces blew large parts of it up – the ruins made it even more attractive to the Romantic imagination.

At the foot of the cliffs beside the river, a concrete arch stands riddled with bullet holes, a memorial to all those who died trying to swim the Morava river to the Austrian side to escape Czechoslovakia. On the back are the names of more than a hundred people who met that fate on this heavily guarded section of the border.

Georg Frank comes out of his castle to welcome me. He's younger than I expect, too young to have taken part in the 1984 protest movement against the Hainburg dam, which made this park and his job possible. As manager of the Donauauen national park, he oversees the water levels, the trees and beavers, the fish and owls and frogs and little creeks of this stretch of woodland.29 He drives me down half overgrown tracks in a red park-authority jeep into the restricted area of the woodlands. Then we walk for a while together, two grown men in a sea of snowdrops. I pick a handful to sniff. They do have a faint scent, but nothing like the full-blooded linen of Babadag. These ones are made to delight the eyes, not the nose. Next time we stop the car we hear the woodpeckers straightaway. Each plays a different, rattling note on the tree, depending on the hollowness of the wood, the hardness of the trunk, and the power of its beak. Georg lists all the woodpeckers of this wood. The Balkan, black, white and red, the greater-spotted, green and, more elegant, the lesser-spotted, the rarer of the three, and several others; closer, or further away – turning the wood into an echo chamber, a carpenter's workshop.

He takes me to see one tree in particular, with all the reverence of a visit to the queen of the forest. The black poplar only grows on land that is regularly flooded. It gets its name from the darkness of its trunk, which it keeps even in the brightest sunlight. The trunk of this one is surrounded by fallen wood, and there is a lighter brown wound in the back – the work of beavers. The beavers diligently make a ring around the trunk, then saw deeper and deeper with their teeth until the tree falls. There's no danger of that happening with this one, Georg says, though he is impressed by their boldness – attacking one of the oldest trees of this forest. ‘It's too far from the water – they have easier prey along the banks.’ We wander down to the shore of a wide creek and scare two young boar, who crash away through the undergrowth. Since this became a national park, there has been no forestry here – but there are signs of the old forestry in every hybrid poplar, growing tall and thin and disappointing in their uniformity, compared to all the other kinds of poplars. The park authority has decided not to chop down the planted poplars in this section, but to allow the beavers to do the job themselves. And on the far shore, it's clear they are fulfilling their ecological duty with a passion – five or six tall poplars, their bark all gone, on the brink of falling.

Then we go down to the Uferhaus, the River Bank-house, an old restaurant on the shore. The Danube seems male again here, manly, a weight-lifter. The flow is swift – swift enough to attract the dam-builders thirty years ago – and the barges labour upstream, groaning and whispering and grumbling against the current. We choose a table outside and order pikeperch fillets with a pat of garlic butter on each. Not from the Danube, Georg sighs. From ponds in Hungary or Slovakia. There's not enough fish in the main river.

Georg calls Josef, the chief forester. He turns down all offers of food and drink to tell his story. ‘I was born in December 1944. My father was a Sudeten German, my mother a local girl. When the Russians came, he was expelled. My mother and I stayed here. We were very poor. My mother got work looking after the cows for a local landowner, on the far shore, at Haslau. We had a couple of goats of our own, so we could always drink goat's milk. I remember as a child, how much I longed for cow's milk. Now I find out that goat's milk is better for you anyway! … The Russian soldiers used to come down to the shore to catch fish. They were always very kind to us, even shared their bread with us. I remember it was black, very different to ours, and had a funny taste. They had a very crude way of catching fish. They would throw a couple of hand-grenades into the water, and the explosions killed lots of fish and brought them floating to the surface. Then they would gather them in big boxes, load them into the back of their trucks, and drive away again. What the Russians didn't realise was that the bigger fish, that were just stunned by the explosions, only floated to the surface an hour or so later. So we children would take those home. Or take them to the restaurants to sell!’

His first income, at seven years old, was from selling fish to the restaurant outside which we now sat. Then he got a job in forestry, on the same estate as before, which in the meantime had been nationalised. ‘As a forester?’ I ask. ‘A wood-hacker, rather!’ he grins – the lowest of the low. He learnt to plant fast-growing trees in straight lines, and was even sent to Novi Sad and the forestry school in Osijek, to learn how to grow trees even faster, even straighter. ‘The speed was all that mattered. Plant them, watch them grow, bulldoze them all down, plant new ones.’

When the protests against the planned Hainburg dam broke out in the early 1980s, and the Austrian prime minister granted a ten years' pause for reflection, Josef was suddenly out of work. He and his colleagues would have had the job of clearing all the forests on both sides of the river, to make way for construction – the same trees which the young Austrian environmentalists were climbing and chaining themselves to, to stop the bulldozers. So Josef started commuting to Vienna, where he got a job in a bread factory. In the meantime at Orth, 110,000 people pooled their savings to buy the forest to create the national park. One day Josef got a phone call from the director. Would he meet him for a drink? Over a cup of coffee, in middle age he was offered the task of undoing his life's work, of helping the forest return to something like its natural state, of overseeing the removal of artificial barriers, the natural reflooding of the forest and the destruction of the straight lines of his youth. The one thing he, as forestry manager, was no longer allowed to do, was to plant or cut down trees. ‘It was strange at first, very strange. You have to look at trees in a very different way … letting them grow by themselves, fall by themselves, slowly rot into the forest floor. And the most amazing thing was, as we let this happen, how all the wildlife re-appeared in the forest.’

Another man cycles by and Georg calls him over. Martin has long hair, partly hidden in a woolly hat. He's on his way home after a hard day's work, but spares us some minutes. Martin and his wife have just finished restoring a water mill, now moored on a creek a few kilometres upstream. How had they done it? With passion, he says. And madness!

While we talk, Georg is feverishly tapping the keyboard of his mobile phone. ‘She says yes!’ he suddenly announces, excitedly. He has just arranged for me to go owl-spotting with the girls tonight. So as darkness falls I find myself in the pleasant but rather unexpected company of Christina, who is writing her PhD on owl behaviour, and a Latvian student on work experience, bouncing down a dark track, ever deeper into the forest. At one point a whole herd of deer – I count at least eight – is scattered by our approach, leaping lightly away down the sides of the grassy dyke, some to the left, some the right. We stop, watch them regroup cautiously, then walk peacefully away into the forest. A little while later we take a right turn, down into the forest again, until we reach a clearing which Christina reconnoitred earlier. There she sets up her own recording and broadcasting equipment. The plan is to play the calls of different kinds of owl, so that real owls living in the wood will assume their territory has been infringed upon and will come to examine the intruders. It's a starry night, but only a small pool of stars is visible above the ring of trees. First Christina plays the sound of a male tawny owl. The cry is long and mournful, the recording one of her own. It echoes through the forest, like ripples in water. I imagine the ears of the entire forest twitching in response, including fellow owls and their prey. But there is no reply. Next she tries the call of an eagle owl, a bigger, fiercer bird. Almost immediately, a long, low hoot comes in response – but of a different note. ‘It's a tawny!’ she whispers. Now she turns on the recording equipment, which looks like a small, curving satellite dish. Soon it is calling, closer and closer to us, though its wing beats are completely silent. As it approaches, we hear the higher pitch of a female tawny, following the male through the forest. Then the two of them settle, effortlessly, in the tree next to us. We can see them clearly outlined against the starry sky. A few nights earlier, on a similar expedition, an eagle owl flew so close over her head she had to duck down, she says.

Every owl, not just every kind of owl, has its own voice, and she has trained her ear to recognise individual birds, Christina explains. She makes careful notes in a log book, complete with GPS coordinates, and the sounds which attracted each owl in turn, with the light of a spotlight attached to her forehead. A thin, pretty girl, humorous … birdlike. We make some more owl sounds, record some more. While waiting for the owls, our eyes peeled on the heavens, we identify the constellations. The tawnies we saw were just under Gemini, twin stars blinking in the darkness. The girls will stay out all night in the forest, going from place to place, but I should press on, to Vienna. They drive me back to my car in the village of Stopfenreuth. ‘How did you get interested in owls?’ I ask. ‘I am an owl,’ Christina says simply, with only a trace of a smile around her mouth. ‘I don't need to sleep at all at night; I like to sleep till midday …

We bid one another birdlike farewells; the girls go back to their dark wood and their birds of prey, and I plunge across the Danube bridge towards the highway and the bright lights of the Austrian capital.

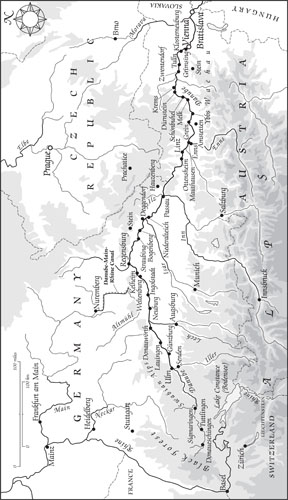

4. The Upper Danube from the castle at Devin to the source of the river in the Black Forest.