8

Citizen Science for the Sharks

“Zero-data” is documenting the absence of something—in this case, sharks. And this data is vital for the SharksCount program. . . . If you go on a dive and see no sharks, please record that dive on your datasheet and report it to us. All your diving information is valuable.

—Michael Bear, citizen science project director, Ocean Sanctuaries, San Diego, California

At Lake Travis at Volente Beach Water Park in Leander, Texas, audiences float in inflated inner tubes to watch a movie. Yep, it’s a swim-up movie! And it’s none other than Jaws. Sharks still make the hair rise on the back of many people’s necks. Yet various factors have raised interest in and love of sharks—from the documentaries of Jacques Cousteau; the popularity of aquariums; the work of ichthyologists such as Eugenie Clark, Robert Hueter, Chris Lowe, Simon Thorrold, and Greg Skomal; to the increase of recreational scuba diving and snorkeling. Discovery Channel’s yearly Shark Week is part of the fun too.

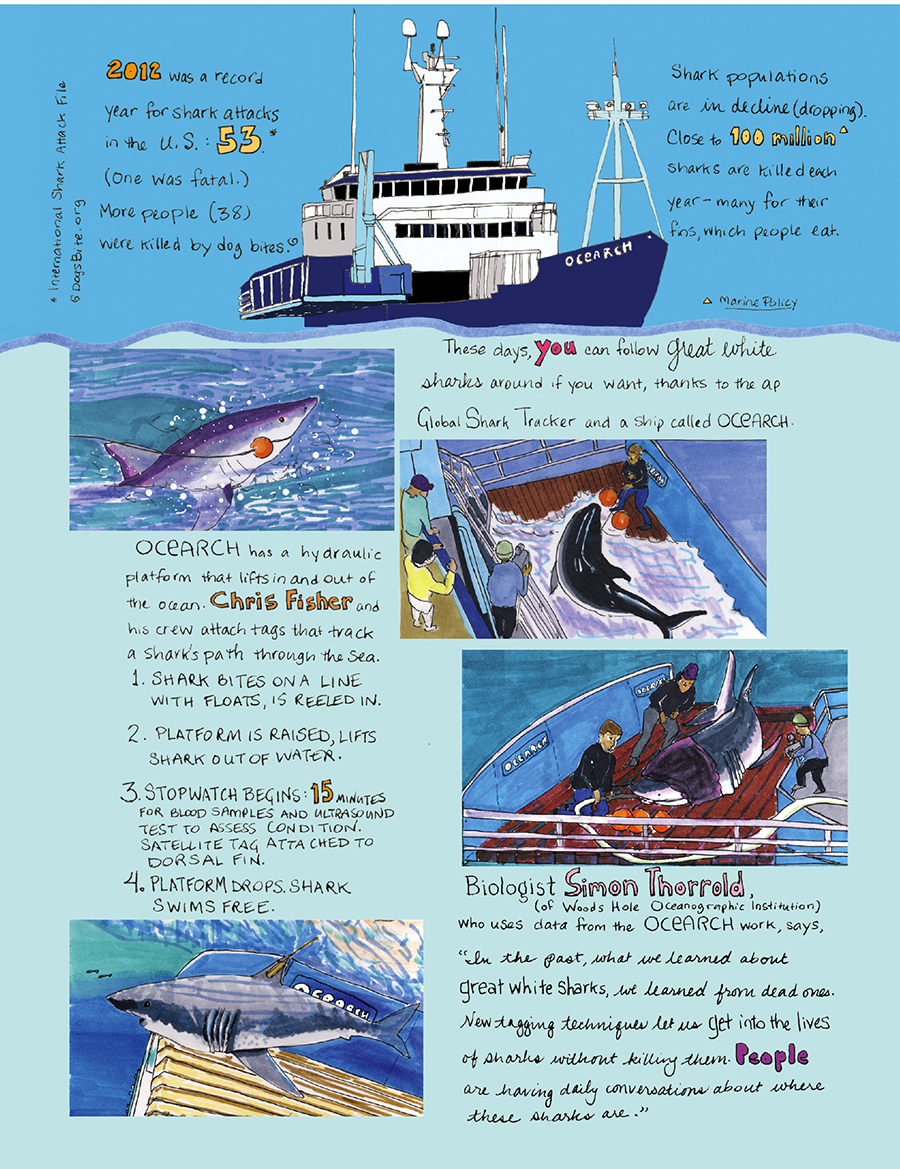

New technologies including acoustic tagging and animal-borne cameras allow researchers to unlock the mysteries of sharks’ lives, which they can then share with the public through social media. Whew! While some people may always be terrified of sharks, many more have come to understand that sharks and their superpowers are not so scary after all. In fact, they are vital to the health of our oceans and therefore of our shared planet.

Shark tourism is on the rise. These scuba divers in a shark-viewing cage watch a great white shark in the Pacific Ocean off Mexico’s Guadalupe Island.

Along with new technology, shark scientists have another major tool to rely on: a public that is fascinated by sharks and that uses the Internet to connect. As citizen scientists realize what sharks are up against, they are putting aside their fears and changing activities that are harmful to sharks. They are also using their senses and learning new skills with new tools to add valuable information to scientist databases.

How can you help sharks? Go look for some!

No joke. For example, citizen divers and snorkelers share their observations, smartphone pictures, and GoPro videos with scientists, who add this information to their data. As new technologies develop, such as drones, early adopters share what they find with experts. Having all these extra eyes and cameras over and under the sea saves scientists time, effort, and money. The information helps ichthyologists confirm—and protect—shark habitat.

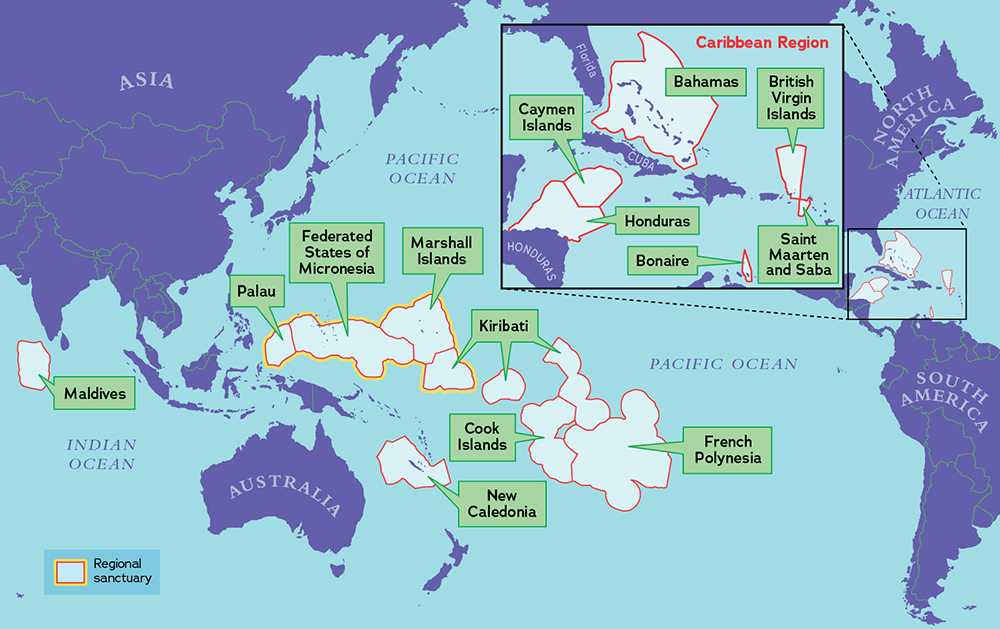

Some citizen scientists are also helping researchers tag sharks. Tagging helps scientists figure out where sharks go. Establishing shark habitat gives fisheries a better idea of when and if shark fishing is impacting the animal’s populations and by how much. Are fleets fishing too many sharks? Or are they limiting their catch to be sure to maintain a healthy shark population? Habitat information is also key to figuring out which areas of the ocean should be set aside as marine sanctuaries. These protected areas are safe for sharks and for people who want to see them. Sanctuaries limit fishing, hunting, shipping, boating, and other human uses to keep environments as natural as possible for wildlife.

Shark Fishing for Science

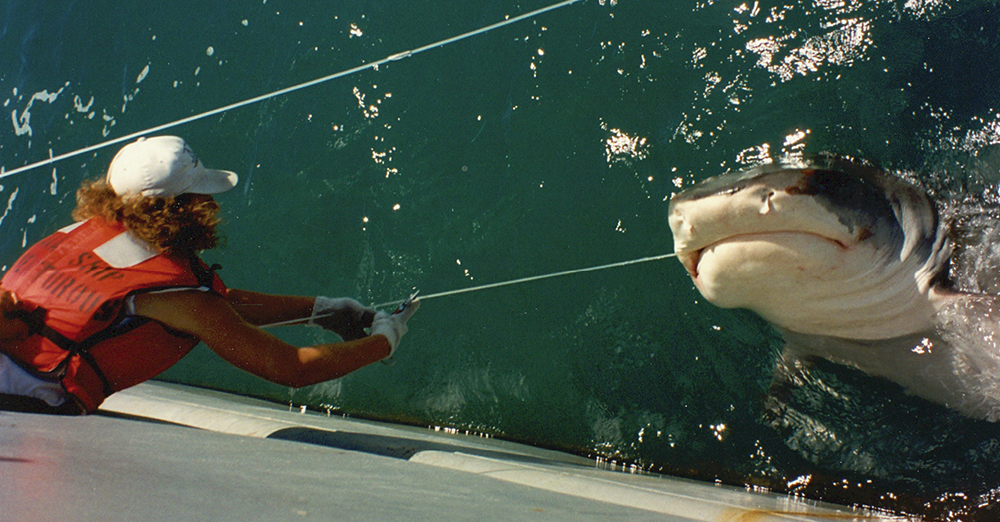

Recreational and commercial fishers team up with researchers from the Cooperative Shark Tagging Program (CSTP), a project run by the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS). Together they study shark species of the Atlantic Ocean. The recreational fishers catch sharks, usually with rod and reel. They attach Rototags (small plastic identification tags) to the fins for recording the shark’s species, size, and location. Usually commercial fishers end up recatching the tagged animals as bycatch in nets or with lines, and they know to report on the tags to the Cooperative Shark Tagging Program. Biologists and volunteer observers sometimes recatch the tagged sharks too, usually with rod and reel.

Scientists with the NMFS compare the locations of tagging and recatch to understand shark migrations. Besides the distance the animals travel (and some idea of route), the data aids scientists in figuring out shark diversity (which species are where), and abundance (how many of each kind are in an area). Information about shark age, growth, and mortality also help researchers understand a typical shark’s life span.

The Cooperative Shark Tagging Program began in 1962. Scientists recruited one hundred volunteers, and by 2013, they have tagged more than 243,000 sharks of fifty-two species. They had also recaptured more than 14,000 sharks of thirty-three species. A sandbar shark holds the record for the longest time between tagging and recapture—27.8 years. The record for distance traveled goes to a blue shark, recaught 3,997 nautical miles from where it was first tagged. (A nautical mile is equal to 1.15 miles, or 1.85 km, so this is 4,600 miles, or 7,402 km.)

Nancy Kohler, head of the Apex Predators Program (part of the Cooperative Shark Tagging Program), captures a tiger shark during a research survey.

Monsters in Danger

Not everyone who catches a shark is doing so for the benefit of science and education. In 2015 the Guardian newspaper reported that towns in the East Coast of the United States still host seventy-one well-attended monster tournaments. Corporations typically sponsor these competitions where sports people catch and kill large pelagic sharks including porbeagle, mako, and threshers. They hang them on giant hooks on docks to show off their catch. The prize money goes to the person who catches the biggest specimen. Officials with the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) say the tournaments are okay. The number of catches is limited, and populations of sharks in the areas where tournaments take place are large enough to stay healthy.

Yet marine ecologist Sarah Fowler, former chair of the IUCN’s Shark Specialist Group, told the Guardian, “It seems inappropriate for big commercial sponsors to be sponsoring the killing of a threatened species when it’s not necessary. You can have tag-and-release tournaments instead and thereby contribute to research programs.” And Sharon Young, the marine issues coordinator for the Humane Society of the United States, told the Atlantic magazine that seeing dead sharks for only entertainment bothers her because “we understand that they are a fragile species.”

A Bigger Thrill

Some citizens feel they are helping preserve sharks through ecotourism. These trips focus on vacations to places with an intriguing ecosystem. For example, people wanting to scuba dive with hammerhead sharks will vacation close to waters where the sharks live. The tourists pay for hotels, food, souvenirs, and activities in the local community and contribute to the local economy. National Geographic magazine estimates that the existence of one live hammerhead shark in the wild in Costa Rica’s Cocos Island brings in $1.6 million a year from ecotourists who want to see it. So a single live shark is far more valuable than a single dead shark, which is worth about $200 to a fisher selling it at market. Thousands of scuba divers come to the sanctuary at Palau to see grey reef sharks, bringing about $2 million to the community every year. When caught by fishers, the dead sharks are worth about $108 apiece.Yet fishing fleets need the income they earn from their work, so tension exists between the fishing industry and ecotourism.

Shark-related tourism more than doubled since the late 1990s, growing to $314 million a year in the second decade of the twenty-first century. It is projected to more than double in the next twenty years, to $780 million a year. Meanwhile, the worldwide shark fishing industry (worth $630 million annually) is in decline because of increasing pressure to conserve sharks. So fisheries economist Andrés Cisneros-Montemayor of the University of British Colombia in Vancouver predicts that shark ecotourism will soon be worth more than global shark fisheries. “The emerging shark tourism industry attracts nearly 600,000 shark watchers annually, directly supporting 10,000 jobs,” he says. “Leaving sharks in the ocean is worth much more than putting them on the menu.”

Shark Sanctuaries of the World

Local Heroes

Ecotourism is one way of preserving sharks. A program in Bimini, a chain of islands in the Bahamas, takes things a few steps further. The Watermen Project, collaborating with the Bimini Biological Field Station Sharklab, invites teenagers to tag great hammerhead sharks and bull sharks. The teens are also trained to take muscle samples from the fish. The work involves skills that many people in Bimini already have. They know how to spearfish with precision and how to free dive (dive without a scuba tank). So they are

excellent at approaching sharks without scaring them. The teens use a dart gun to attach an acoustic tag to each shark. Acoustic receivers planted on the seafloor pick up the pings from the transmitters to show which sharks are where. The teens also use a biopsy gun to snatch a muscle sample so that scientists can analyze the shark’s DNA.

In her work with sharks, South African marine biologist Alison Kock uses knowledge she picked up as a kid. “When I was very young,” she recalls, “I used to accompany my dad on boat trips to harvest crayfish. We would spend hours at sea, deploying nets and waiting for the crayfish to climb inside. When we retrieved the nets, it wasn’t only crayfish that we found, but small sharks too. The little sharks would curl up into a ball with their tail covering their eyes and my dad instructed me to kiss them on the head and gently release them back into the water. When I did so, the shy sharks would uncurl and swim back down to the bottom.” As a student in college, seeing a great white shark launch itself 6.5 feet (2 m) into the air to nab a seal convinced her she’d found her research topic. As an adult, Kock not only studies great whites in False Bay, South Africa, she is also the project leader for the Save Our Seas Foundation. This organization works to protect life in the ocean, especially rays and sharks.

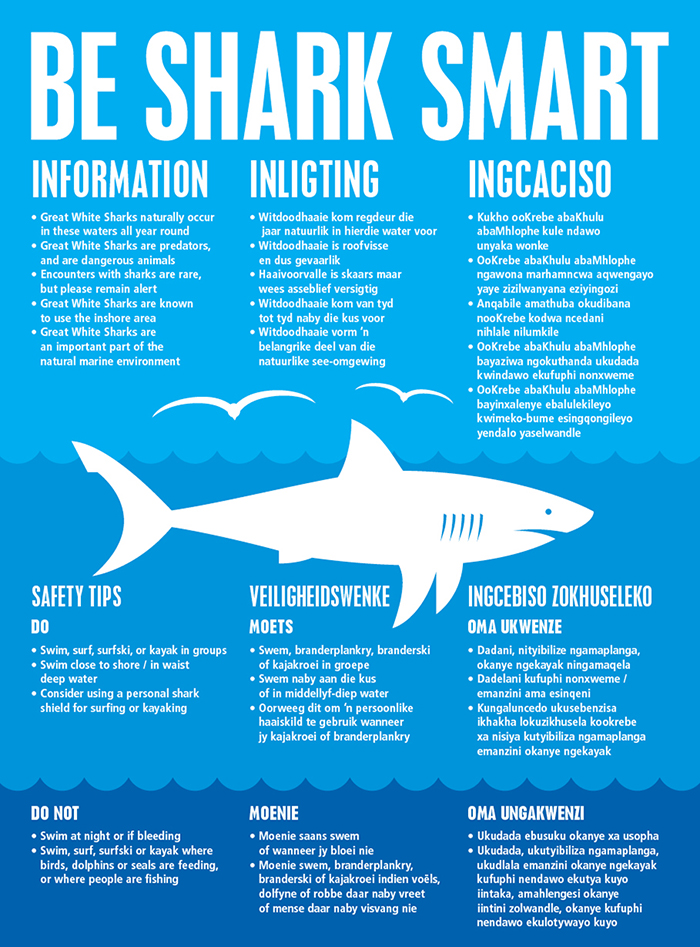

Shark Spotters “Be Shark Smart” posters are on South African ocean beaches to provide safety tips and information about how to behave appropriately in waters where sharks live.

Alison Kock also attaches tags and Crittercam cameras to the fins of great whites as part of her scientific work. And she manages the shore-based Shark Spotters Programme in Cape Town, South Africa. Started in 2004, the program employs people to spot sharks for research as well as to protect swimmers at area beaches. Her program was among the first in the world to train and hire citizen scientists.

Cape Town is home to four million people, including lots of water-loving folks who kayak, surf, windsurf, kiteboard, dive, and fish along the rugged, gorgeous coast. The Atlantic Ocean there is home to great white, bull, and tiger sharks, among the most aggressive shark species. The members of the Shark Spotters Programme use binoculars to monitor beaches at nearby Table Mountain, the main feature of the popular national park of the same name. Shark spotters keep an eye out for sharks, using a flag to advise beachgoers of the level of shark risk. For example, a white flag with a black shark on it means the beach is closed because a shark is in the water. One of the goals of the Shark Spotters Programme is to prevent harmful incidents between sharks and humans so that the public attitude toward great whites will improve. A more positive understanding of sharks is an important part of shark conservation.

“In the beginning, back in 2004, most of us knew very little about shark behavior in False Bay, and we came a long way. . . . Now the public is very supportive and it is just from time to time that we get one or two people who are arrogant or ignorant and ignore our calls,” says Monwabisi Sikweyiya, a lifeguard and one of the program’s first spotters. Sikweyiya is Shark Spotters’ field manager. His advice in case you unintentionally encounter a shark in the water? “Don’t paddle, just float. If you’re lucky enough, the animal will just swim away. But white sharks are ambush animals; they can take you by surprise.” In 2016 Shark Spotters began work on a new app that will let beachgoers check conditions before setting out for the shore.

Good Eyes

Data gathered by nonscientists is proving to be very reliable and is becoming an increasingly vital contribution to the understanding of the world of sharks. Citizen scientists are helping fill in some of the blanks. For example, in 2014 Gabriel Vianna and his associates at the University of Western Australia, Perth, learned that the IUCN had categorized almost half of the 1,041 known species of elasmobranchs (sharks and rays) as Data Deficient. This means that ichthyologists don’t know enough about their abundance (numbers) or distribution (habitat range) to determine the health and stability of individual elasmobranchs species. The IUCN makes designations about the conservation status of Earth’s animals, from Not Evaluated and Data Deficient all the way to Endangered and Extinct. Nations around the globe make decisions about whether and how to protect their oceans, based in part on IUCN rankings. Icthyologists therefore feel pressure to come up with better information to help the IUCN and nations make their decisions about animal life on Earth.

The Perth scientists were studying grey reef sharks in Palau. They decided to bring in citizen scientists to help with their project. So Vianna’s group asked local dive guides to observe and count sharks. They also asked them to gather information about the strength of the sea current and the temperature of the water. Telemetry (automated communications) buoys in the area would measure this same type of information. Vianna’s group wanted to know if the data from the divers and the buoys would match. And would the presence of divers in the waters scare sharks away or tempt them to come close?

The data was good news for the divers. It showed that their presence in the water neither frightened away nor attracted sharks. The presence of sharks varied according to sea conditions. So, in rough waters, divers saw few if any sharks. In calm waters, they saw more. And it was good news for scientists too. The results from the acoustic technology and from the divers were comparable. So the data gathered by nonscientists was reliable, and scientists could use it in their shark assessments.

In other areas of ocean science and in other parts of the ocean, citizen observations have been a big help. For example, the Reef Environmental Education Foundation (REEF) uses data gathered by divers and snorkelers to determine the health of reef ecosystems. They report on invasive species such as lionfish, which can destroy reefs. When lionfish are located, efforts to remove them can begin. On Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico beaches that attract sea turtles, volunteer monitors gather data about the turtles as they emerge from the ocean to dig the sandy nests in which they lay their eggs. The volunteers also protect the nests from people or animals that try to dig them up. And along the bluffs of California’s Pacific coast, whale watchers with binoculars keep an eye on migrating gray whales. Increasingly, scientists are finding ways to involve citizen scientists in new research.

Citizen scientists include tourists watching the waters along coastlines, from cliff tops, or from boats and sharing what they see with experts.

Spying on Sevengills

Michael Bear started one of the world’s first citizen science shark projects. In 2009 he began hearing a lot more big fish stories than he ever had before. From divers in the San Diego area, he was hearing stories about sightings of data-deficient broadnose sevengill sharks. He realized the stories might be true. “I was diving off of Point La Jolla when a large seven footer [2 m] sevengill shark glided majestically between me and my dive buddy, who was no more than two meters [7 feet] away from me,” Bear wrote. “To say we were startled would be an understatement.” Sevengills are a shallow-swimming shark usually found near shore. Fishers were catching them, but this species was unprotected because not enough was known about them. So, in 2010, Bear founded the Sevengill Shark Identification Project to turn divers’ stories into data. He hired Vallorie Hodges, an expert on diving with sharks, as the project’s lead scientist.

The first step was to invite citizen divers to photograph the head and gills of sharks in the wild without endangering their own (or the sharks’) safety. An essential part of the project was to figure out how to then collect and organize information and photographs coming in by the Internet from divers. For help, Bear consulted Jason Holmberg—the same information architect who had worked with marine biologist Brad Norman and Ecocean on whale shark photo identifications for Wildbook. Holmberg expanded his software-driven Wildbook database to give citizens an open-source (copyright-free) platform for uploading and sharing their snapshots and sightings of sevengill sharks. As with whale sharks, this version of Wildbook analyzes spots on shark bodies. If it confirms the distinctive black freckles around the sevengill’s eyes, the program can make a positive identification of each individual shark.

Together, the divers and scientists generated databases of photos, videos, and identifications. The work went so well in San Diego that ichthyologists and citizen scientists in False Bay adopted the project to track sevengills there. The smartphone app Sevengill Shark Tracker also helps scientists gather more data quickly.

Playing to the Crowd

Bear went on to launch Ocean Sanctuaries in 2014 with recreational and science diver Barbara Lloyd. The ocean conservation organization is focused on species conservation, ocean sustainability, and citizen science projects. It also makes documentary films about the ocean. Ocean Sanctuaries invites citizen scientists to use an online mapping tool called FieldScope to upload images and data about leopard, horn, angel, tope, blue, mako, great white, and thresher sharks. They say, “Surprise us!”

Crowd-sourced research, or information gathered online from many people, contributes to growing sites such as the Encyclopedia of Life (EOL). The main goal of EOL is to combine scientist and citizen images and information to create a page for every species on Earth. Anyone with photographs and information about sharks (or other animals) can share them there. Before the EOL site will post them, scientists vet them to confirm the contributor’s observations. So far, EOL has close to 5.6 million pages. Citizen science organizations such as Shark Stewards in California work with iNaturalist, an online social network of scientists and citizens committed to preserving biodiversity. Together, they collect and share data about sharks and rays. The site has observations of more than one hundred thousand species by more than one hundred thousand observers worldwide.

The Latest Shark

Stop the presses! A new shark species has been discovered! In a study led by Florida International University, ichthyologists determined in 2016 that they had found a new species of bonnethead shark, a type of hammerhead shark. Scientists studying bonnetheads in the Caribbean waters off the coast of Belize realized that the genes of the bonnetheads in this area differ from bonnetheads in other parts of the Caribbean and in the Atlantic. The IUCN lists bonnetheads as of Least Concern because they are abundant. But the realization that bonnetheads in Belize are a different species altogether calls this label into question. A closer look may reveal that so few of this newly discovered species exist that it requires protection of its habitat.

“Determining when you have a new species is a tricky thing,” study author Demian Chapman told Mental Floss magazine. “But these sharks are living in a separate environment from their fellow bonnetheads, and they’re likely on their own evolutionary trajectory.”

Discoveries such as these were once made only by scientists. But as citizens worldwide become more involved in observations of wildlife and as conservation efforts improve the world for sharks, scientists are moving over to make room for—and invite—contributions from shark lovers everywhere. After all, the more we know about sharks—and the less we are ruled by fears not based in reality—the more we can love, value, and protect them.