CHAPTER SIXTEEN

Men of Honor

SULTAN ABDERRAHMAN HAD TO DECIDE which he feared the most: French reprisals for not fulfilling his treaty commitments, or his subjects’ bile for not supporting the emir’s jihad. The sultan also worried that Abd el-Kader had designs on his throne, which made it easier for him to do France’s bidding.

Abderrahman’s imagination was not working unassisted. Many of the tribes were not happy with his capricious rule. Along the eastern frontier were thousands of Algerian émigrés whose sympathies for the emir could be unpredictably roused from the dormant to the active state by the slightest movement of Fortuna. Rumors were circulating in the bled that Abd el-Kader might replace the apostate sultan, who preferred compromise with the infidel French over support for jihad. Yet, Abd el-Kader was his father’s son. And his father had practiced his belief that all authority, whether good or bad, is ordained by God. Bad authority was better than no authority. The sultan would have to abdicate first.

Abd el-Kader was also a hunted man who had to keep moving in the summer of 1847. Rif tribes were pressured not to trade with the emir’s deira, his foraging parties were attacked and even a murder plot was hatched. The emir headed southeast, back toward the Moulouya River along Morocco’s frontier with Algeria. The sultan ordered an attack at Ahlaf. When Abd el-Kader saw the huge Moroccan campsite, he struck first. The next night, he scattered the Moroccans by stampeding into their camp hundreds of panicked camels harnessed to bundles of fagots that had been set on fire.

Abd el-Kader made one last, desperate effort at reconciliation with the sultan. In early November, Bou Hamidi volunteered for a risky peace mission to Fez. He was to appeal to the sultan in writing and remind him of the sacred traditions of hospitality, of the bonds of friendship and religion and the deep respect the emir and his father had always shown to the sultan. With little hope and much sadness, Abd el-Kader said goodbye to Bou Hamidi, sensing that he might never again see his faithful caliph.

For six days, the sultan kept the ex-caliph of Tlemcen waiting as if he were the lowliest delivery boy. Once granted, the audience became stormy and Bou Hamidi was thrown in prison. A return message was sent to Abd el-Kader telling him to surrender to the sultan in person or return to the Algerian desert. If he refused, the sultan’s army would march against him.

The emir’s choices were few. The year 1847 had been marked by submissions. In February, his caliph Ben Salem had finally submitted. He had been convinced of the futility of continued fighting by his son, who had studied in France after he had submitted in 1843. In April, Bou Maza had surrendered to Saint-Arnaud. Abd el-Kader’s brother, Mustafa, had taken refuge with the sultan.

Bugeaud had resigned that year as governor-general, but there was no relaxation of the pressure. Opposition to the general’s ideas about colonization, fatigue and the unrelenting nipping at his heals by his many enemies in the press and outside, had driven him to ask to be relieved of command. In May, he had announced to the population of Algiers: “My health and the situation caused by opposition to my views make it impossible to take charge of your destinies. I have asked the king to send my successor.” His replacement was the man he had recommended: the Duke of Aumale. Younger and gentler, he was no less dedicated than Bugeaud to total domination.

As the odor of despair in his deira became stronger, Abd el-Kader sought wisdom and understanding where he always found it. He spent much of his time in prayer or surrounded by his remaining devoted followers — a hard core of 200 battle-hardened infantry and 1,200 cavalry, who had lived through the same trials of mind, body and spirit as he. When not praying and exhorting his followers to endure, Abd el-Kader would remain alone in his tent. At night, the emir was heard frequently reciting the holy book he had learned by heart as a twelve-year-old.

A violent winter rainstorm was pelting the emir’s tent, where he gathered his council the evening of December 21. An important decision needed to be made.

To the west, a frightened and hostile sultan was marching with a new army to chase him back to Algeria. To the east, the tribes had all

gone over to the French, seduced by the new governor-general’s policy of generosity and reconciliation. No more uprisings in the Ouarsenis Massif, the Medea or Kabylia were possible. The intrepid Ben Allal was dead, his only caliph to die on the field of battle. Ben Salem and Bou Maza had submitted. To the north was Lamoricière. The only escape was south, into the Sahara, where they would get help from friendly factions of the Beni Snassen. Once through the Guerbous Pass, Abd el-Kader could make trouble indefinitely with 1400 men willing to fight to the bitter end.

But that day, Abd el-Kader’s scouts had returned with surprising news: two squadrons of Lamoriciére’s spahis already occupied the pass. They had exchanged their usual red burnooses for white ones to be less conspicuous to the all-seeing locals who would normally report enemy movements to the emir well in advance. Now the spahis would alert the general in case Abd el-Kader fled into the desert. Though Lamoricière had 3,000 cavalry, Abd el-Kader was informed they were twelve hours away.

His brother-in-law, Ben Thami, Bou Klika, the caid of Tagdempt and Kaddour Ben Allal, a cousin of the caliph, all wanted to attack. The few troops opposed to them could be easily overcome. Once through the pass, they would reach the friendly Beni Snassen. However, Abd el-Kader knew that the inhabitants of the deira would not get through. They were at the end of their strength. So too their horses and camels, which had been reduced to bags of bones. The sick and wounded, the women and children were weak and hungry. Their families would be taken prisoner. He and his men could still create trouble, but to what end? To continue the resistance, some chiefs argued, even if it meant sacrificing their families. To never give up.

Abd el-Kader reviewed the past with them. He reminded them of the vow taken eight years earlier after Tafna was violated — to struggle and endure no matter how great the danger and the suffering. It had been a mutual commitment. The caliphs nodded in agreement.

But the emir thought otherwise.

“I don’t think any Muslim can accuse me of not doing everything possible to honor that vow. If there is anything more I can do, tell me.” A long silence acknowledged he had done everything in his power.

“Believe me, the fight is over. We must lay down our guns. God is our witness that we have fought as long and as hard as we could — so long as there was hope of liberating our country. But most of the tribes have quit the struggle. My own brothers have submitted to Lamoricière. Now Muslims are killing Muslims. The sultan has imprisoned our brother in arms, Bou Hamidi, massacred the Beni Amer and sold their wives into slavery. The French kept their word after Ben Salem submitted. I would rather put my trust in those whom we have fought against than those who have betrayed us.

“If I thought there were still a possibility to defeat France, I would continue. Further resistance will only create vain suffering. We must accept the judgment of God who has not given us victory and who in his infinite wisdom now wants this land to belong to Christians. Are we going to oppose His will?”

In the early hours of December 22 , a young officer of the spahis was straining to see into the wintery murk. Lieutenant Bou Khouia was proud that General Lamoricière had entrusted him to guard the pass that would be the emir’s only escape route. Messengers had told him that the emir was following behind with three of his chieftains. He was going to ask for Lamoricière’s aman.

As Bou Khouia and his detachment of spahis rode forward, they suddenly found themselves gazing at the famous emir as he emerged from behind two spots of light made by lanterns tied to the end of long poles. The emir had only one condition for his surrender: that he, his family and followers who chose exile with him, be given a free passage to a Muslim country. He would give his word to never return to Algeria.

Abd el-Kader pulled a piece of paper out from under his burnoose, but the downpour, howling wind and dervish dance of the lanterns made it impossible to write. Instead, he stamped the paper with his seal and told the lieutenant to report his terms to Lamoricière. Bou Khouia rode as fast as the darkness permitted to his general’s advancing main column. Lamoricière could not write in the storm either, nor could he find his seal. So he gave the lieutenant his saber and the seal of a fellow officer to take back to the emir. Bou Khouia was to tell Abd el-Kader that the Frenchman’s aman had been granted.

The rain had slacked off when Bou Khouia returned to the emir’s camp. Abd el-Kader dictated his response to Ben Thami, asking that the general write in his own language “words that cannot be changed or diminished” guaranteeing passage either to Saint John of Acre or to Alexandria, and nowhere else. “… I am ready to sell my camels, mules, horses, and other things belonging to me or my family when others who wish to come with me are free to do so. Please take care to try to liberate Sidi Mohammed Bou Hamidi as soon as possible so that he might accompany me.” Abd el-Kader returned the general’s sword with his letter.

Bou Khouia galloped back to Lamoricière with the emir’s response. This time, Lamoricière had his seal. The general sent word to the governor-general, expected to arrive at Djamaa Ghazaouet by sea, of the commitments he was making in his name. The general knew and respected the prince well enough to be confident that he would ratify them.

“I have the order of the son of the king of France, may God protect him, to grant you his aman and to grant you passage from Djemaa Ghazaouet to Alexandria or Acre. We will not take you anywhere else. Come when it is convenient, day or night. Do not doubt our word. Our sovereign will be generous towards you and your family…As for Bou Hamidi, I will send a boat to Tangier with a letter for the French consul requesting Sultan Moulay Abderrahman to free him…”

The morning of December 23, Abd el-Kader was getting reports telling him that his chiefs at the deira had gone to Lamoricière promising submission and asking protection. Spurred by knowledge of the emir’s surrender, some tribes had pillaged his deira. Lamoricière sent a cavalry detachment to protect the remaining families.

Abd el-Kader was anxious. He dreaded having a spectacle made of his surrender in front of the French army. Rather than go east toward Lamoricière, the emir headed north, where he believed his deira was located. Riding with him were Ben Thami, Bou Klika, agha Kara Mohammed and some sixty other chiefs. Abd el-Kader called a halt when they reached the ridge overlooking the valley where two years earlier Colonel Montagnac’s cavalry had been slaughtered. Below them was a knoll where the French had formed a square to make their last

stand, and where a wounded commander Courby de Cognord had had his life saved by Bou Hamidi. Further west across the valley was the white dome of Sidi Brahim where the Chasseurs d’Orléans had languished for two days without food and water. The snow-covered Trara Mountains could be seen to the East.

For an hour, the emir and his men waited, plunged in thought, gazing silently at the immense sky and open countryside. There was much to think about: their past struggles together, their families, the uncertain future that awaited them, to join or not the emir in permanent exile. Some would never see again the ocean of green, rolling hills speckled with olive orchards spread before them.

A column of cavalry came into view, moving at a steady trot. Abd el-Kader ordered two men to find out who they were and who their commander was, but only after waving their burnooses as a sign they wanted to talk.

The column was under the command of Colonel Cousin de Montauban, who had been guarding the emir’s deira all night from pillagers. Montauban was a name familiar to the Arabs. He was one of the few French officers who spoke competent Arabic, and had been the officer chosen to escort the emir’s brothers, Hussein and Said, to the French camp two days earlier. The emir sent back word that he wished to talk with him. Montauban agreed, proposing they meet on the knoll, each with an escort of fifteen men. After the customary greetings, Abd el-Kader asked abruptly if Lamoricière would keep his word. Montauban replied that it was not customary for French officers to break their promises. In any case, he was going to meet Lamoricière and could take the emir with him, speaking as if his decision to submit was a fait accompli.

Before leaving, Abd el-Kader asked the colonel if he could go down to the marabout and pray. The Frenchman agreed. As they approached the site, Montauban drew up his 500 chasseurs into two rows. With the colonel on his left, and Ben Thami and several other chiefs trailing behind, the chasseurs saluted as the emir rode by. “If I had men like these fine soldiers, I would now occupy Fez,” the emir told Montauban.

The wall around the marabout tomb was scarred from the bullets of two years earlier. Abd el-Kader removed his sword before he entered, bending his head to go through the small door leading into the mausoleum

of Sidi Brahim. An hour later, the emir stooped out into the light. His unsought-for career as a warrior and nation-builder was over.

While Abd el-Kader was praying, Montauban had been sending messages — one to Lamoricière informing him that the emir was now in his company, another to Djemaa Ghazaouet asking that tents be pitched nearby at Äin Safra for the emir’s family. During their brief time together, the emir learned to appreciate the French officer’s delicacy and good manners. Mountauban’s Arabic was remarkably good, even for someone who had served in Africa for fifteen years. His eighteen-year-old son had lived with Arabs growing up and was widely known and respected among the tribes for his knowledge. Montauban’s unplanned arrival on the scene proved to be a godsend for Lamoricière. A less-adroit officer could have spooked the emir, whose horses, even when tired, could always outrun the French.

The distant rumble of a cannon signaled the Duke of Aumale’s arrival at port. A message from Lamoricière came telling Montauban to go immediately to Djemaa Ghazaouet. Abd el-Kader hesitated, became stubborn. He refused to go. A humiliating surrender in front of the whole army unnerved him. Montauban understood the emir’s position and applied the emir’s own principals to dislodge him. What would he have done to an officer who refused to obey him? the colonel asked. That was the position he was being placed in before his own commander if the emir didn’t cooperate. But Montauban also understood the emir’s pride. They would surely meet Lamoricière en route, he added, well before they arrived at Djemaa Ghazaouet. Relieved by Montauban’s assurances, the emir mounted his black mare.

The emir and his chiefs were passing in front of the marabout when, unannounced, trumpets sounded and 500 chasseurs drew their sabers as one. A startled Abd el-Kader asked if they were going to all be killed. A tribute to the men who had died there, Montauban assured him. They had barely left Sidi Brahim when a cloud of dust announced the arrival of Lamoricière at the head of a small detachment.

Abd el-Kader dismounted when the general approached. Lamoricière did the same and walked forward to greet him in Arabic. At forty, he was the youngest general in Africa, one of the brightest stars in the French army, committed to serving God and France. The famous Bou Herawa, “The Father of the Stick” ( the only weapon he carried when

among the Arabs), was about the same height as the emir, though of stockier build. He cut a dashing figure in his red tarboosh, dark-blue field coat and red pants. His black eyes flashed an authority that had made him feared and respected by tribes throughout Oran. The emir handed Lamoricière his sword and ordered his men to lay down their guns at the general’s feet. Visibly moved at the sight of these legendary warriors, their burnooses smudged with gunpowder and blood, submitting in dignified silence, Lamoricière told them to keep their weapons. “Use them to serve France. I will enroll you at once in our makhzen.”

Lamoricière escorted the emir to Djemaa Ghazaouet. Tremors of excitement and barely controlled glee were almost visible among the French officers trying to maintain a dignified solemnity as Abd el-Kader rode with an air of calm resignation in the chilly dusk. His life had been one of surrender to a Higher Power, and that Higher Power had now decided that France should rule Algeria.

Accompanied by Lamoricière, Cavaignac and Colonel Montauban, Abd el-Kader was led through a small garden to a candlelit cottage where the twenty-five-year-old prince waited expectantly. Abd el-Kader hesitated as he looked at the distinguished figure before him. The prince was the same age as he had been when he declared jihad fifteen years earlier only he had blond hair and a face as smooth and delicate as a girl’s. “I would have liked to have done earlier that which I have done today,” the emir offered after a moment’s hesitation, “but I awaited the hour appointed by God. The general has given his word and I have put faith in it. I am not afraid it will be violated by the son of a great king.”

“I affirm what the general has said to you — that you will not be kept captive and you will be taken to Saint John of Acre or Alexandria. And if it pleases God, so it will be; but this requires the affirmation of the king and his ministers. I will report what has been agreed and send you to France to await orders from the king.”

The emir excused himself, saying he was tired and wanted to see his family whom he had not seen since they had crossed the Moulouya River. He was taken to nearby Äin Safra where he explained to the remnants of his deira the agreement he had concluded: that they would sail

for the Middle East the next day, and those who wanted to accompany him could do so. All their personal belongings — tents, horses, mules, camels — would be bought by the French.

The next morning, the Duke of Aumale reviewed his troops as they paraded around the little pocket of land the Arabs had named a “gathering of pirates,” or Djemaa Ghazaouet : Zouaves in white spats, cherry-red pantaloons and navy blue vests; Legionnaires in red pants, gold-buttoned blue field coats; white-turbaned spahis in Fez-blue tunics under crimson vests and cloaks — maneuvered against a gleaming sea that seemed to dance in the early morning light. After the review, the young prince rode over to Abd el-Kader, who had been watching the demonstration of that admirable discipline that his own troops too often lacked. The emir sprang down from his black mare when the duke approached.

“I offer you this horse, my last to ride into battle. She is a great favorite of mine, but we must part now. This gift is a sign to my gratitude for your guarantee. I wish it will always carry you in safety and good health toward happiness.”

“I accept it as homage offered France whose protection you will have henceforth and as a sign that the past will be forgotten.”

Before leaving for Oran, where they would be transferred to larger boat, Abd el-Kader found himself a celebrity. Everyone wanted a souvenir — a belt, a knife, a piece of clothing or even an autograph. Colonel Montauban asked for a few lines stamped with the emir’s seal,21 attesting to his considerate treatment at the time of his surrender. Abd el-Kader addressed his words to the colonel’s son, and praised his father’s courtesy.

General Lamoricière accompanied the emir to the landing where he would board the Solon, a small frigate that had brought the prince to Djemaa Ghazaouet and would take them to Mers el-Kebir, Oran’s natural port from where he would continue his voyage. Before parting, Lamoricière handed the emir a heavy purse. It was full of gold pieces

worth 6000 francs, a paltry value for the emir’s personal belongings. Abd el-Kader thanked the general; then, as a final gesture of submission, gave him his sword. To Abd el-Kader, the gesture was a voluntary act in accordance with Divine Will. To France, it was surrender.

The prince wrote to the minister of war that night: “A great event has just taken place. Abd el-Kader is in our camp. This is a matter of immense importance. It is something most of us dared not believe could happen. It is impossible to describe the tremendous effect this has had on the tribes in the region, which will spill over into all Algeria,” adding, “I have the firm hope that the government will ratify it.”

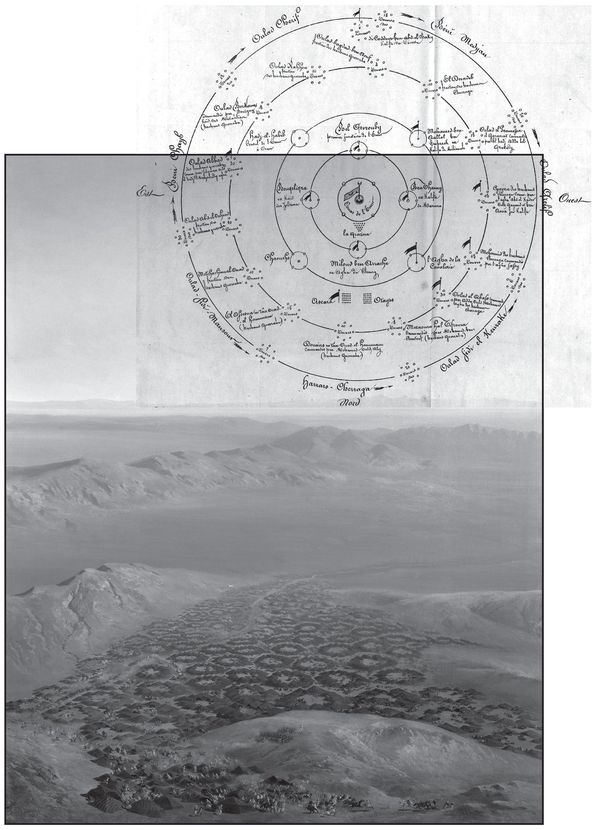

Composition and installation of the Smala d’Abd el-Kader (plan).

Location; Musée Condé, Chantilly, France

Photo Credit : Réunion des Musées Nationaux / Art Resource, NY

Panoramic view of the capture of the Smala of Abd el-Kader by the Duke of

Aumale at Taguin, May 16, 1843.

By Jean Antoine Simeon Fort, 1847

Location; Chateaux de Versailles et de Trianon, Versailles, France

Photo Credit : Réunion des Musées Nationaux / Art Resource, NY

Location; Chateaux de Versailles et de Trianon, Versailles, France

Photo Credit : Réunion des Musées Nationaux / Art Resource, NY

Return of the Duke of Aumale from the Mitidja Plain after the capture of the Smala of Abd el-Kader in May 1843

Engraving, Location; Chateaux de Versailles et de Trianon, Versailles, France

Photo Credit: Réunion des Musés Nationaux/ Art Resource, Ny

Photo Credit: Réunion des Musés Nationaux/ Art Resource, Ny

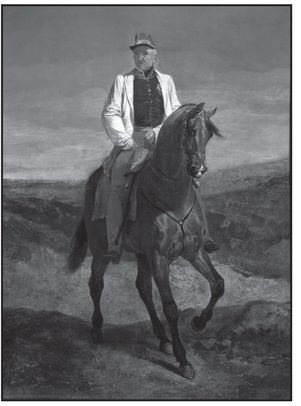

General Bugeaud

Carle Vernet. Location; Musée de l’Armée, Paris, Photo Credit: Musée de l’Armée/Dist. Réunion des Musées Nationaux / Art Resource, NY

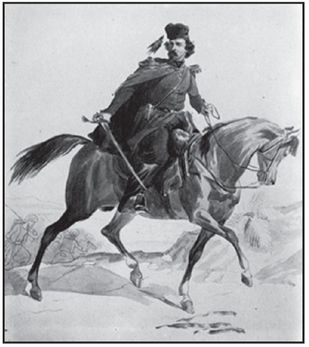

General Lamoriciere Location; Chateau de Chillon,

Switzerland

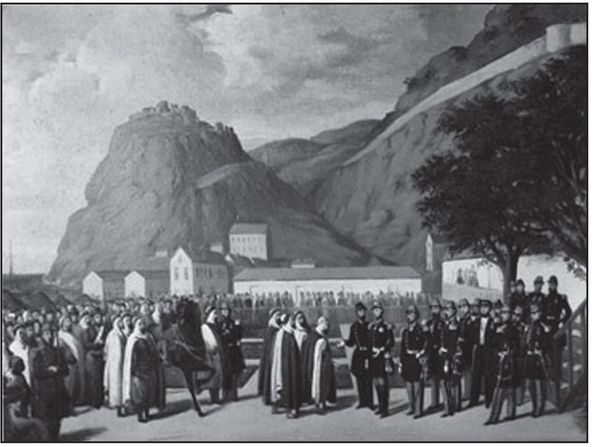

Armistice Ceremony at Ghazaouet, December 23, 1847

Augustine Regis, Location; Musée Condé, Chantilly