One

FORT APACHE,

CROOK, AND COOLEY

The US military knew next to nothing about White Mountain Apaches or their isolated mountain homeland in 1869. Army officials believed, mistakenly, that White Mountain Apaches had been aiding the Chiricahuas in raids on white ranchers. In July of that year, Bvt. Col. John Green of the US 1st Cavalry was sent north from Camp Grant with a scouting party of 120 men with orders to kill or capture any hostile Indians they encountered, and to destroy their cornfields.

As Green’s troopers advanced up the trail from the Black River, smoke signals rose from ridge tops announcing their progress. Shortly after Green arrived at the White River, he had an unexpected visit from Miguel, leader of the Carrizo band, who invited him to visit his rancheria, or village. Green sent Capt. John Barry and a detail back to Carrizo with Miguel with orders to kill anyone who resisted.

To Barry’s astonishment, men, women, and children in Miguel’s camp ran out to greet the soldiers, carrying corn for their horses and inviting them to a feast. Barry’s report stated that he “would have been guilty of cold-blooded murder had he fired upon those people.”

Three American prospectors had been staying in Miguel’s camp. One was Corydon E. Cooley, a former Union soldier, who assured Green that the White Mountain Apaches were peaceful. After conferring with Apache leaders, Green urged the government to establish a military post and reservation on the White River. He argued that it could serve as a forward operating base against hostile bands. Not all Apaches wanted a military presence in their land, but others saw an Army post as an opportunity to earn cash and receive regular rations.

Green chose a bluff at the confluence of the east and north forks of the White River for a camp. He wrote, “I have selected a site for a military post on the White Mountain River which is the finest I ever saw . . . It seems as though this one corner of Arizona were almost its garden spot, the beauty of its scenery, the fertility of its soil and facilities for irrigation are not surpassed by any place that ever came under my observation.”

In May 1870, troops were moved north from Camp Goodwin to begin construction of what was first called Camp Ord. It was not officially designated Fort Apache until 1879. The post was built on 12 square miles of military preserve surrounded by the Fort Apache Indian Reservation.

Gen. George C. Crook, commander of the Department of Arizona, arrived at the post on August 12, 1871. Shortly afterward, he decided to construct a new military road that would connect Camp Apache with Camp Verde and Fort Whipple, his headquarters. As Crook rode off on his Army mule to inspect the route, he ordered Capt. Guy Henry to enlist the first company of 50 White Mountain Apache Scouts. Crook, experienced in Indian warfare, believed it would take Apaches to find other Apaches. The scouts proved to be invaluable in Crook’s 1872–1873 campaigns against Apache groups who continued to raid white settlements. Alchesay, already a respected leader at age 19, was the first of four White Mountain Apache Scouts to receive the Medal of Honor for valor. Others were Machol, Blanquet, and Chiquito. All told, 11 Indian scouts received the nation’s highest military honor during Crook’s winter campaigns.

Corydon E. Cooley served Crook chiefly as a guide and interpreter with the scouts. Cooley was married to two of Chief Pedro’s daughters, Mollie and Cora. Mollie was a cousin of the influential Chief Alchesay.

By 1874, Cooley was ready to settle down to family life. He and a partner, Marion Clark, homesteaded a ranch on Show Low Creek, north of Fort Apache, although Cooley continued to live near Fort Apache and serve the Army. At some point, Cooley and Clark decided to split the partnership and play a game of Seven Up for the ranch. Local legend alleges that they played cards all night until Clark finally told Cooley, “Show low and take the ranch.” Cooley cut the cards and showed the deuce of clubs, winning the ranch and cattle. From then on, the community was known as Show Low.

Cooley’s wife, Cora, died in 1876 following the birth of their daughter Lillie. Cooley formed a partnership with Henry Huning, a New Mexico rancher, and built a large home in Show Low. They raised purebred Hereford cattle, farmed, and ran a shingle mill. Cooley sold his interest in the Show Low ranch to Huning in 1888. He and Mollie moved to land on the Fort Apache Reservation, south of Pinetop, on which Mollie had grazing rights. The Cooleys built a large ranch home that became an overnight stop for military personnel, travelers, and freighters.

Mollie was well known for her cooking, hospitality, and good-natured disposition. Brig. Gen. Thomas Cruse, in Apache Days and After, wrote, “On all my visits their table had groaned under meals of beef, game of all sorts, and civilized incidentals.”

Crook’s aide, Capt. John G. Bourke, wrote, “Cooley’s efforts were always in the direction of bringing about a better understanding between the two races.” Cooley died at his ranch on March 19, 1917. He was buried with full military honors in the Fort Apache Cemetery. He left a legacy of goodwill and an army of descendants.

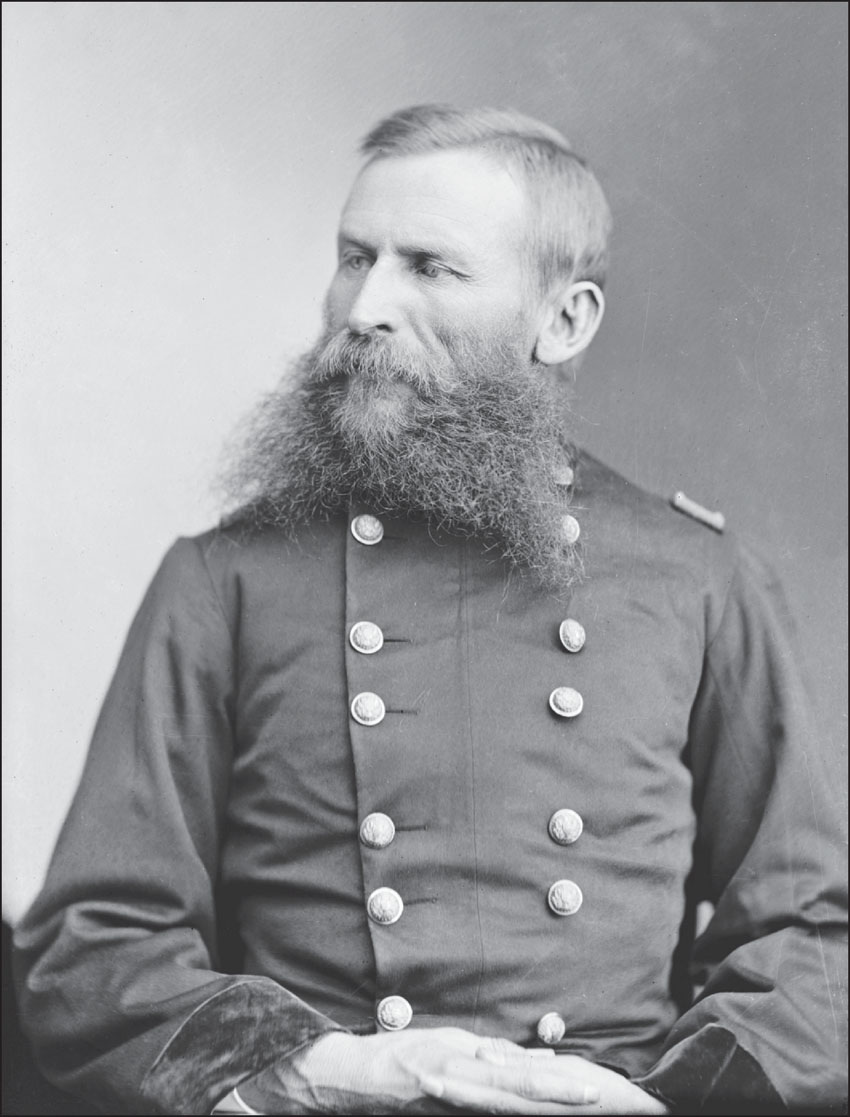

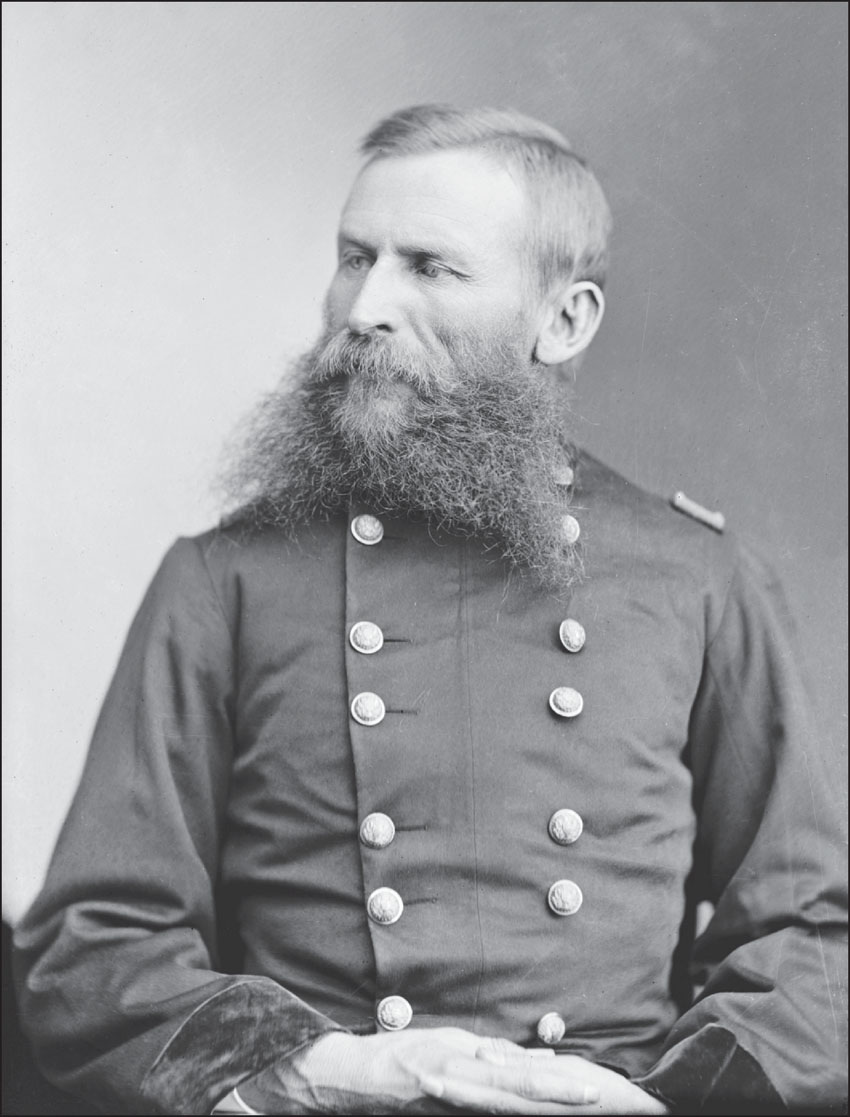

GEN. GEORGE C. CROOK. White ranchers and farmers were looking at the White Mountain Apache homeland as an ideal place to locate, but the defending Apaches held them at bay. Tales of lost gold mines were attracting prospectors as well. Settlers and prospectors wanted the government to solve the “Apache problem.” Government policy was for all Apache bands to be confined in one place, San Carlos. For this purpose, the Army appointed Gen. George C. Crook commander of the Department of Arizona in 1871. Crook believed that the only way the Army could fight Apaches successfully was with other Apaches. He ordered the formation of the first group of Apache Scouts. They were the “special forces” of the time. Carrying supplies on pack mules instead of cumbersome wagons allowed his forces to move swiftly over rough terrain. Scouts moved in small units called flying columns. Crook served two tours in Arizona, from 1871 to 1875 and from 1882 to 1886. (Courtesy Brady-Handy, Library of Congress.)

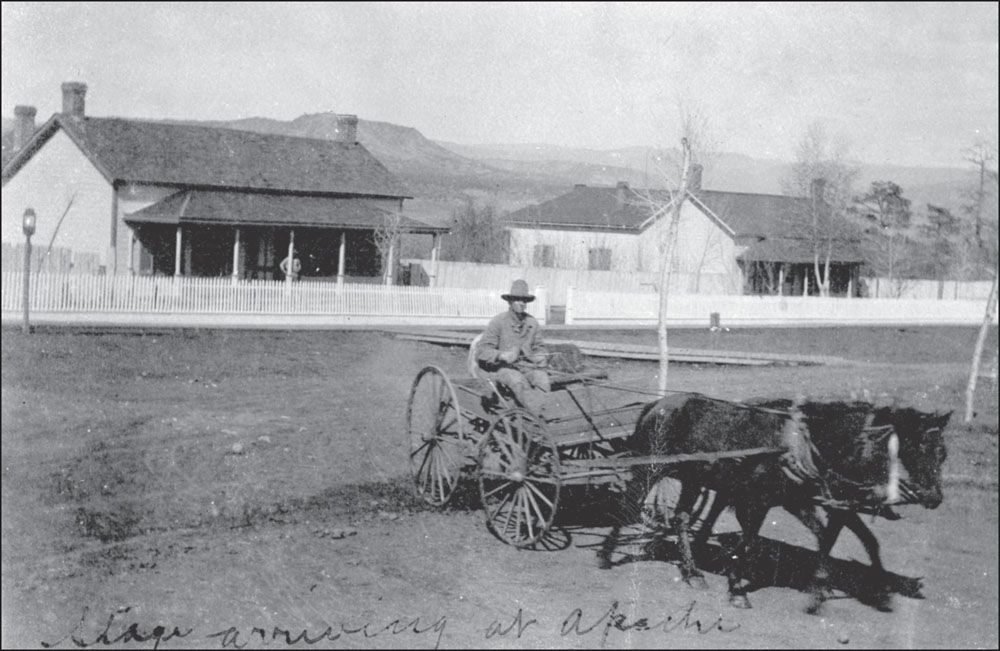

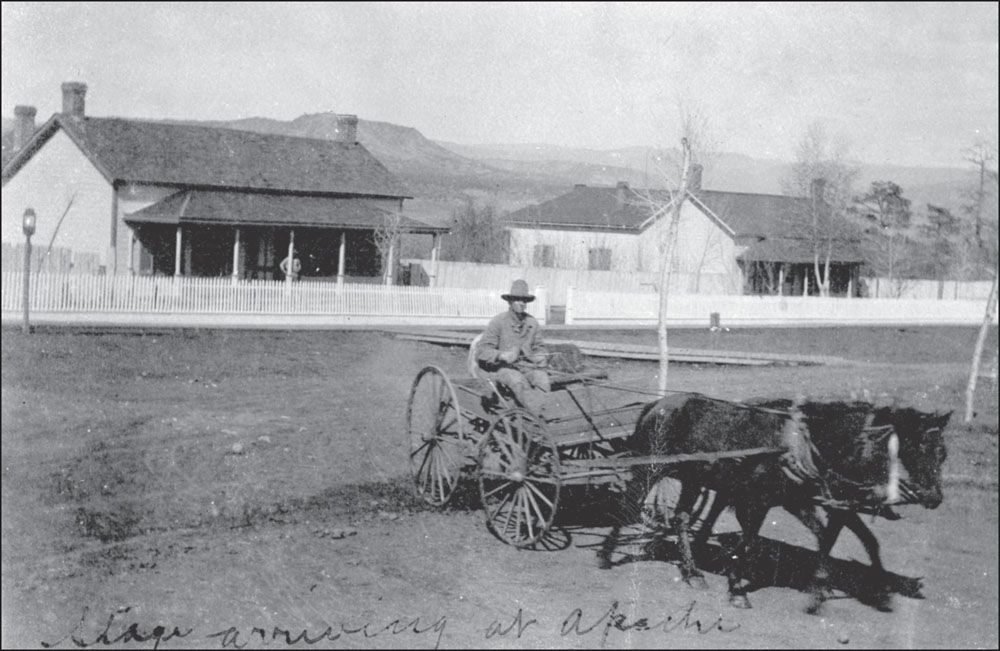

STAGE ARRIVES AT FORT APACHE. Fort Apache was located at the confluence of the north and east forks of the White River in 1870 to serve as a forward operating base for the cavalry to pursue Tonto and Chiricahua bands that refused to surrender to the Army. The camp was established with a dual purpose: to protect white settlers who were moving into the region from Apache attacks, and to protect the White Mountain Apache people from encroachment by whites. Officially named Fort Apache in 1879, it was one of the most remote posts in the West. Official mail was carried by courier, and regular mail was brought in on a stage like the one pictured. (Courtesy Anne Snoddy-Suguitan.)

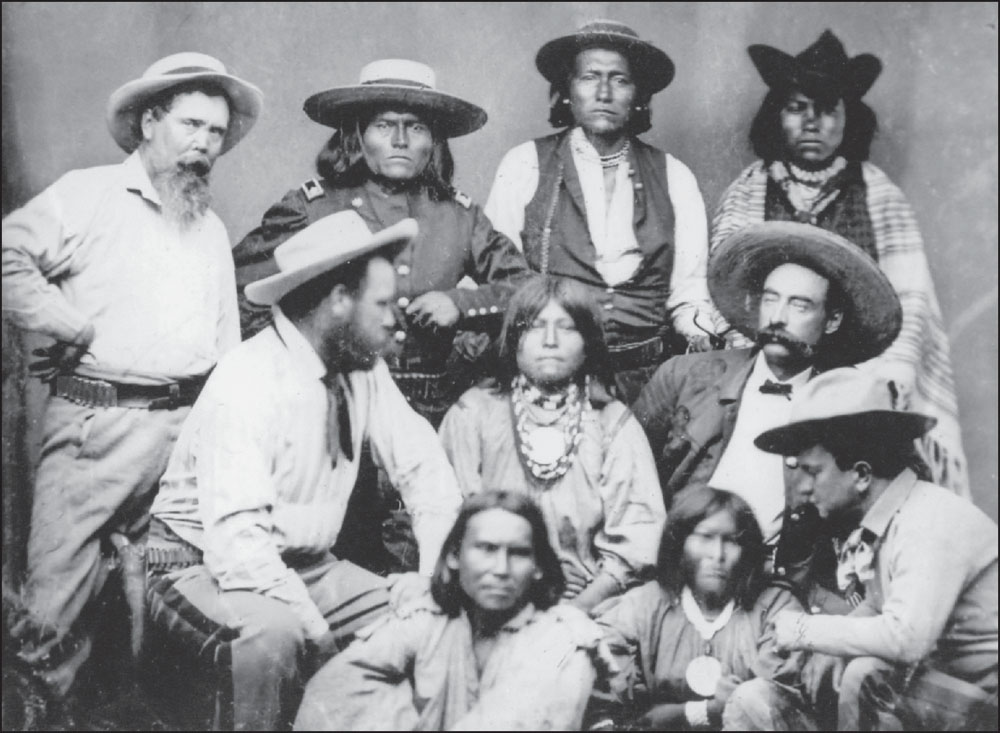

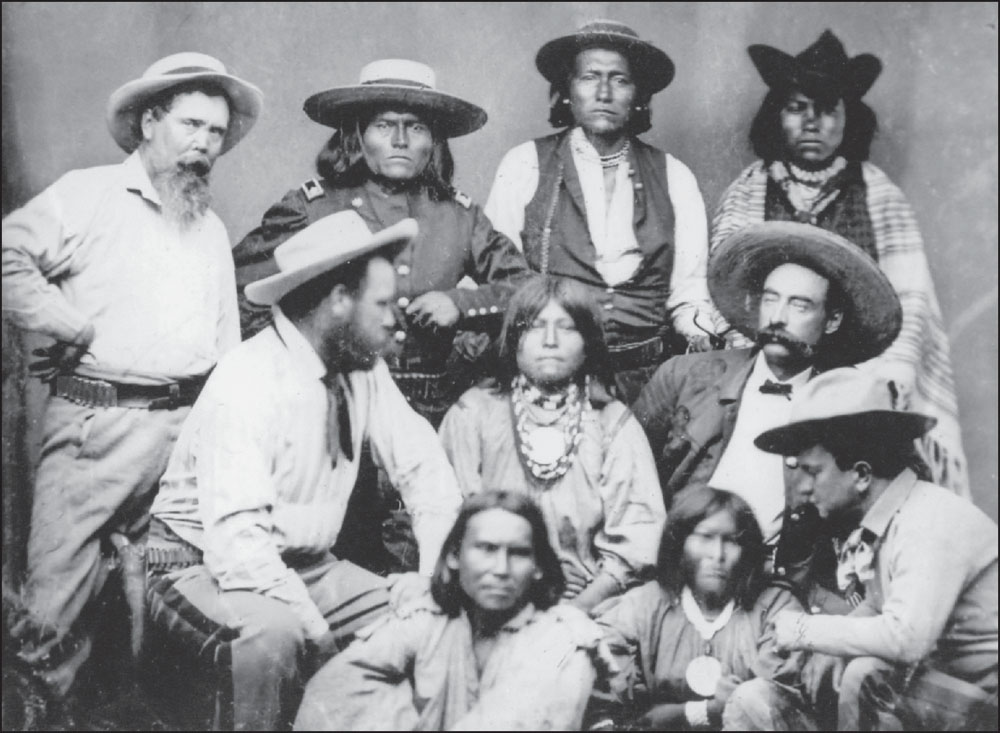

COOLEY AND SCOUTS. Corydon Eliphalet Cooley was a primary force for peace between Apaches and whites in the White Mountains. A first lieutenant in the Union Army during the Civil War, he served with the New Mexico Volunteers as a quartermaster. In Arizona, General Crook hired him as a guide and interpreter for his newly formed Apache Scouts. Cooley befriended Chief Pedro and married two of his daughters, in accordance with Apache custom. Cooley is pictured here at top left. The man with the wide-brimmed hat and mustache is Capt. George M. Randall. (Courtesy Belle Crook Cooley Amos.)

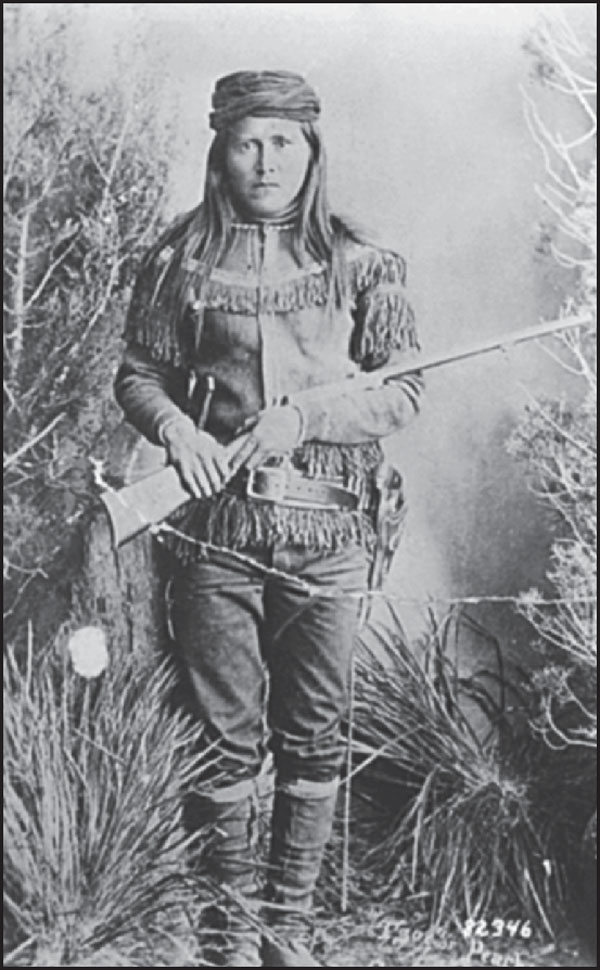

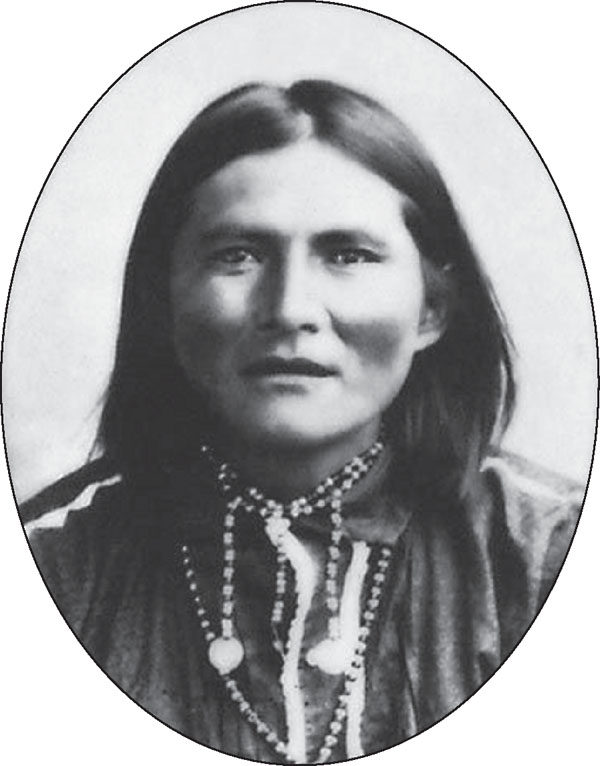

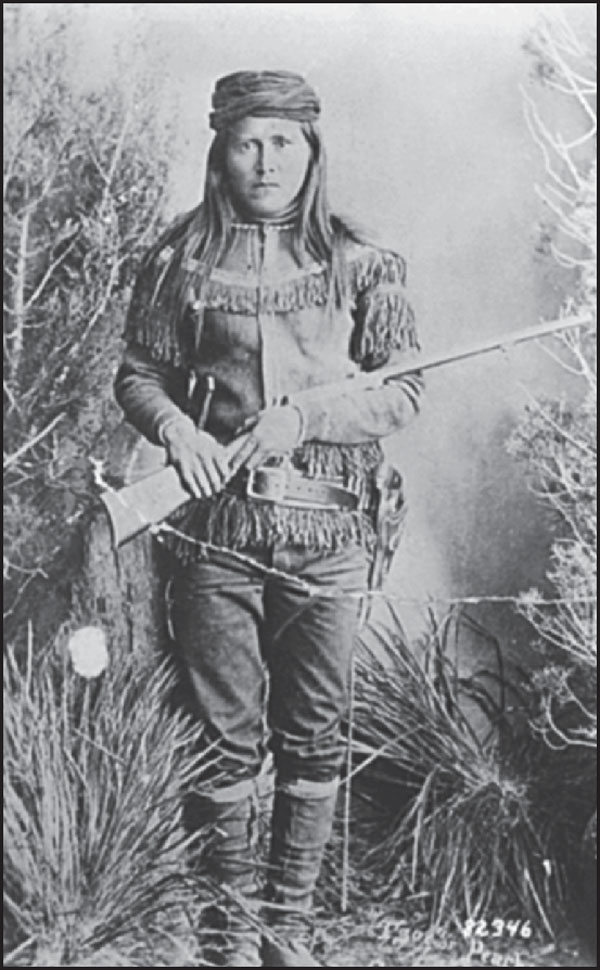

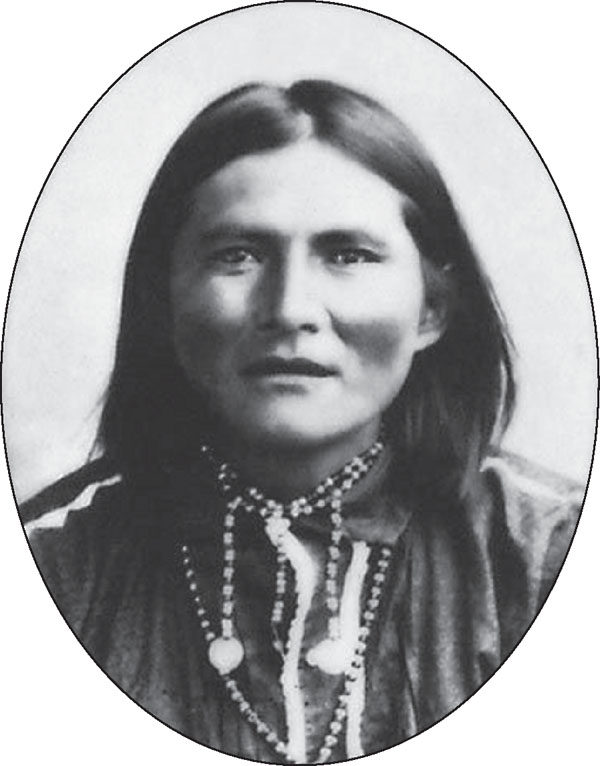

TZOCH “PEACHES,” APACHE SCOUT. Some say that the troopers at Fort Apache nicknamed this White Mountain Apache Scout “Peaches” because he was a handsome young man with a “peaches and cream” complexion. He proved to be invaluable in Crook’s Sierra Madre campaign against Geronimo’s band. Peaches, who had been coerced into fighting with the Chiricahua, was captured without resistance by Crook’s White Mountain Apache Scouts. He led them to Geronimo’s camp deep within the Sierra Madre of Mexico. When the Apache wars were over, he settled down in Cibecue with his wife’s people. In 1933, “Old Man Peaches” was converted to Christianity by Rev. Edgar Guenther and baptized by Evangelical Lutheran pastor Nieman in Cibecue. (Courtesy Ben Wittick, National Archives and Records Administration.)

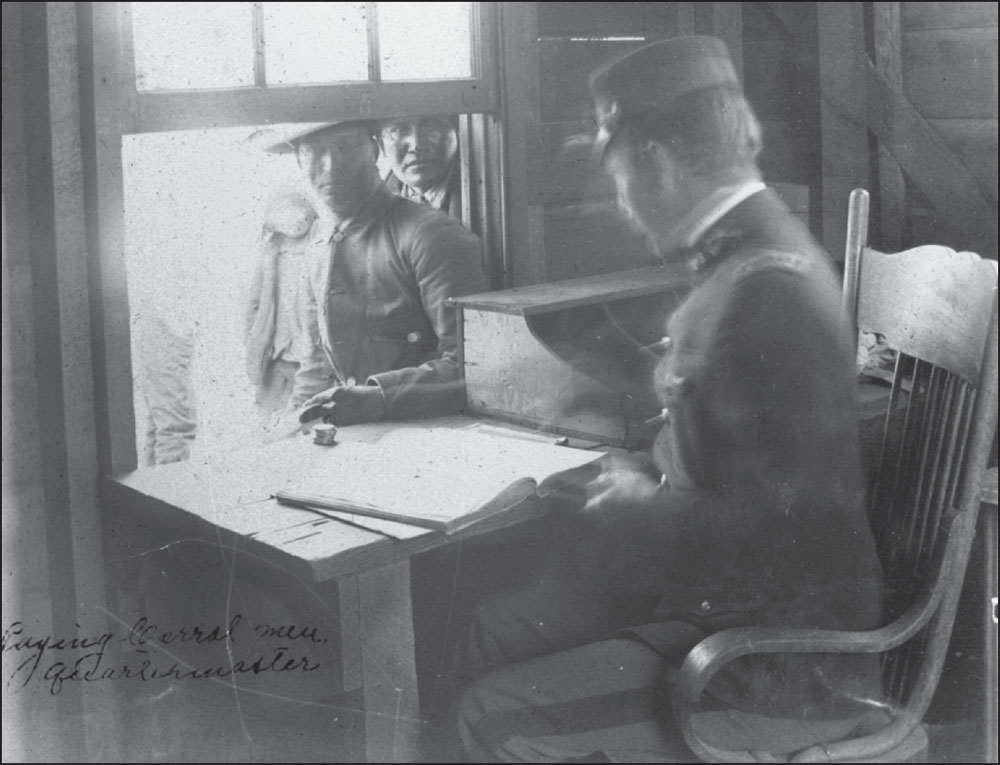

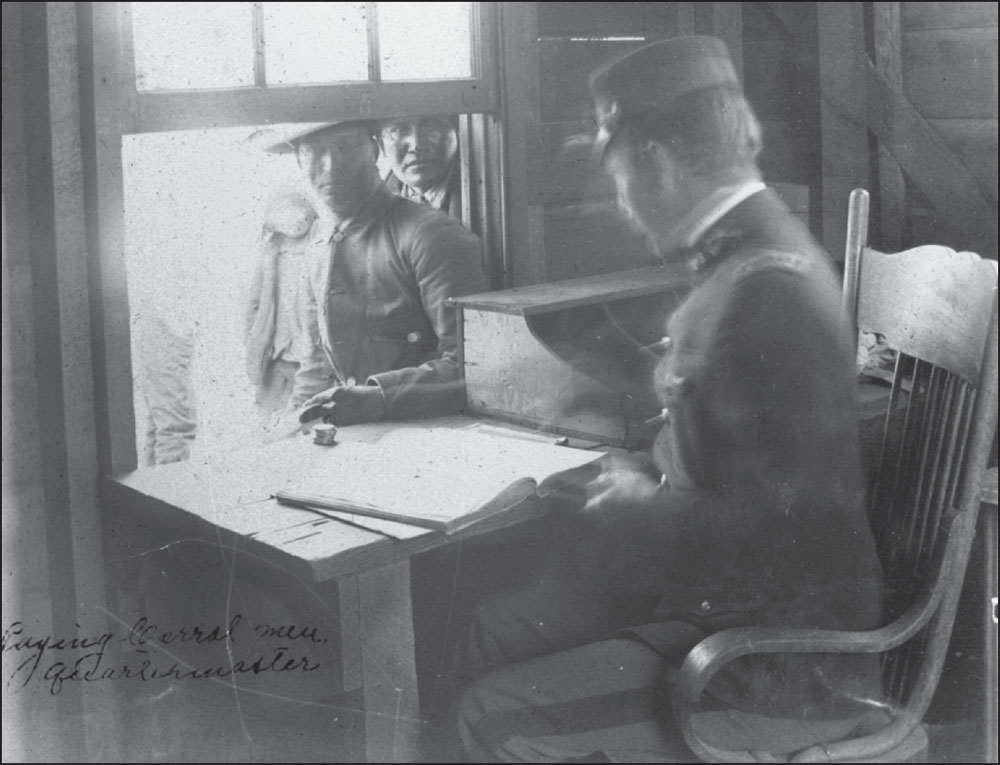

PAYDAY AT FORT APACHE. Cavalry troopers and Apache Scouts collected their pay from the quartermaster’s office. Enlisted men earned $13 a month. If they reenlisted for another two years, their pay was raised to $15. The Army had difficulty recruiting men for frontier duty. Although it was dangerous, it offered a safe harbor for those running from the law or domestic problems, those who had lost home and family in the Civil War, and immigrants. When troopers were not in the field, they were laboring at Fort Apache, repairing structures, cutting firewood, hauling water, and building roads. Much of their time was spent grooming, shoeing, and caring for cavalry mounts and training recruits to fight on horseback. (Courtesy Anne Snoddy-Suguitan.)

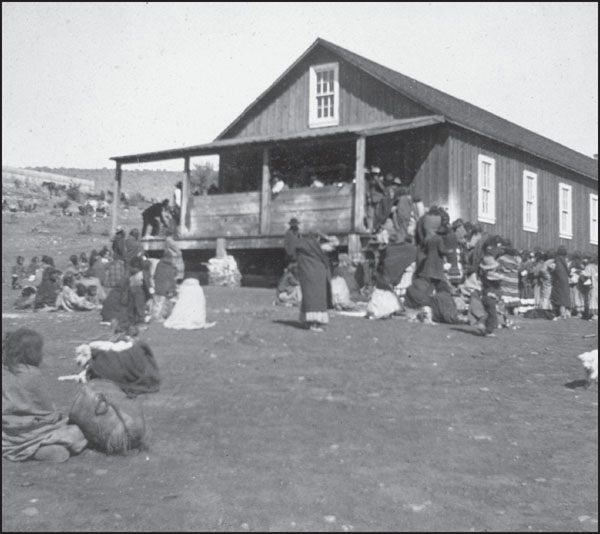

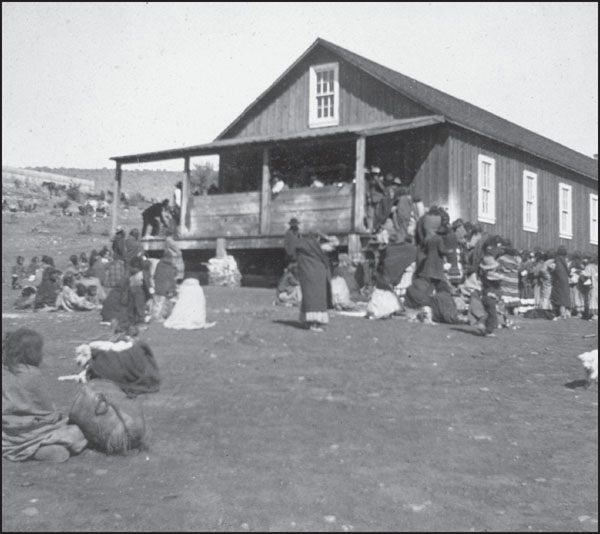

APACHES WAIT FOR RATIONS. Apache families who lived in the area surrounding Fort Apache came into the fort twice a week to get the supplies they were promised by the government. They received rations of beef, corn, beans, sugar, and other staple commodities the government purchased from both white and Apache farmers. Beef was doled out on the hoof. Some Apache families kept their beef cattle instead of eating them and became ranchers themselves. (Courtesy Anne Snoddy-Suguitan.)

APACHES DELIVERING HAY. Cavalry mounts at Fort Apache needed large amounts of hay. This photograph shows Apaches delivering wild hay to the fort. A large amount of the hay fed to horses was cut by hand from native grasses that grew in abundance on the expansive Bonito Prairie. Schoolteachers cut hay to sell to the government as well, as they were not paid in the summer months when they were not teaching. (Courtesy C.A. Merkey, National Archives and Records Administration.)

CHIEF ALCHESAY. Sgt. William Alchesay (1853–1928) joined the US Indian Scouts at Camp Verde on December 2, 1872. He fought in Gen. George Crook’s winter campaign against hostile Apaches in 1872–1873 and was the first White Mountain Apache Scout to receive the Medal of Honor. He also served in Crook’s 1885 Geronimo campaign in the Sierra Madre of Mexico, where he tried unsuccessfully to convince Geronimo to surrender. He and Geronimo were lifelong friends. As an influential chief, he traveled to Washington, DC, three times, speaking on behalf of the White Mountain Apache people and meeting with presidents Grover Cleveland, Theodore Roosevelt, and Warren Harding. His nametag (ID) number was A-1. He worked all his life to establish peaceful relations between whites and Apaches. (Courtesy Carl Moon, Wikipedia, Public Domain.)

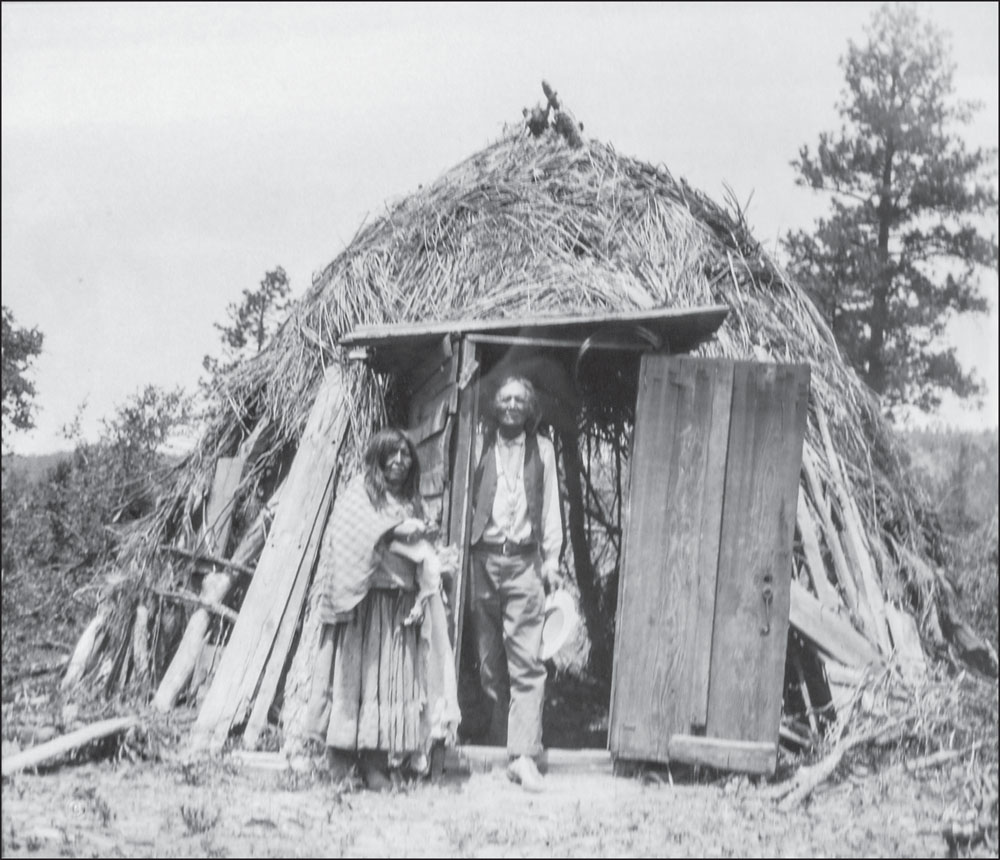

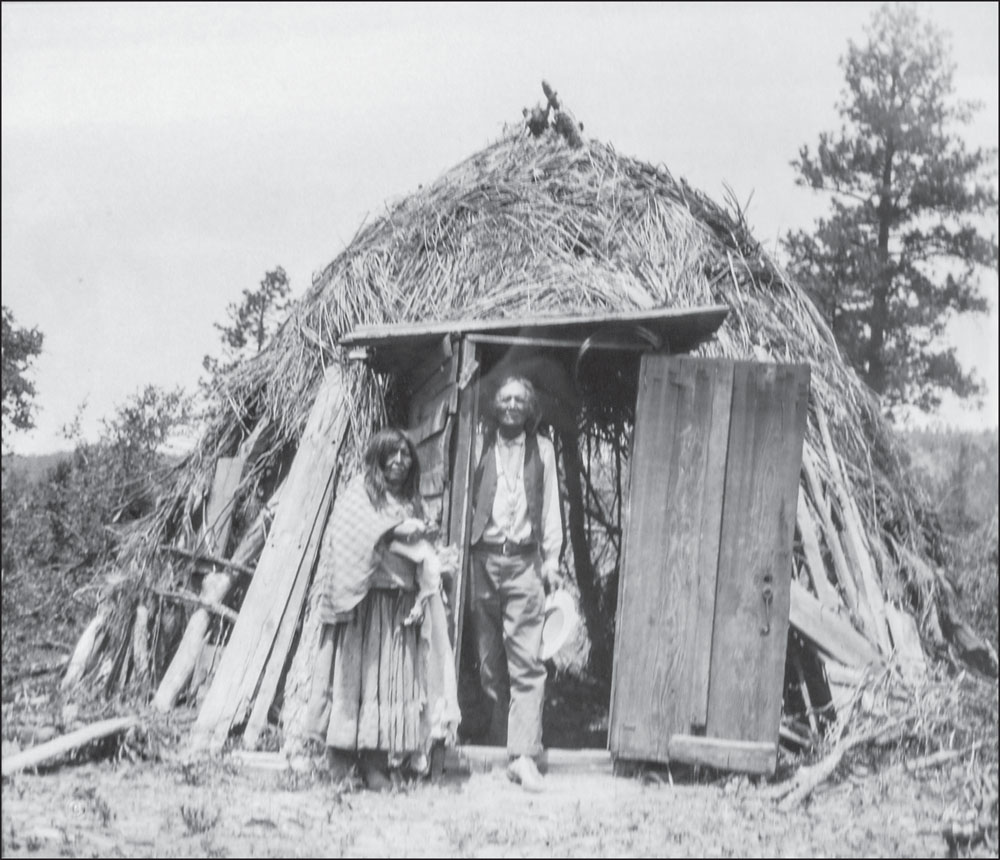

ALCHESAY IN HIS GOWA. At the conclusion of the Apache wars, Chief Alchesay returned to the White Mountain Apache reservation. His first wife, Apache, bore him a son. He later married Tah-jon-nay and her sister Anna and settled down to farming and cattle ranching on the north fork of the White River. Lutheran missionary Edgar Guenther, who became a blood brother to Alchesay, nursed him back to health during the influenza epidemic of 1918. Pastor Guenther baptized Alchesay and 100 of his band in the Church of the Open Bible, in Whiteriver. The pastor named his son Alchesay Arthur Guenther in honor of his friend. Alchesay died on August 6, 1928. Through the efforts of the Pinetop-Lakeside Veterans of Foreign Wars and the Whiteriver American Legion, an official granite Medal of Honor tombstone engraved in gold was dedicated on July 30, 2005, at his gravesite. (Courtesy Gloria Guenther.)