Two

RANCHERS, ROADS,

AND FREIGHTERS

The White Mountains remained silent and undisturbed until construction began on Camp Apache in 1870. The most remote Army outpost in the West required tons of hay, grain, and supplies for the troopers and their mounts. Building materials had to be hauled by wagon from Camp Goodwin to the south. The Army was challenged by logistics.

Entrepreneur Solomon Barth and his brothers Nathan and Morris secured a government contract to haul supplies from Dodge City, Kansas, the westernmost railhead, to Camp Apache. Barth wagon trains consisted of up to 38 Murphy wagons, each pulled by eight huge oxen. Their route took them ever so slowly up the Santa Fe Trail, down the Rio Grande Valley, west to Zuni Pueblo, across the Little Colorado River at St. Johns, on to Springerville, over a wide grassy cienega, through pine forests, and downhill all the way to Camp Apache. The journey took months, but the Apaches received their first rations on time in June 1870.

Fort Whipple, near Prescott, was the headquarters for the Department of Arizona. Military personnel came to Camp Apache from Yuma, on the Colorado River, going through Fort Whipple, on to Camp Verde, up over the Mogollon Rim, through Sunset Pass to the Little Colorado River, east to Horsehead Crossing (Holbrook), and south 90 miles to Camp Apache. Mail and express came slightly faster, by mounted courier or stage. Officers and their families traveled by Army ambulance.

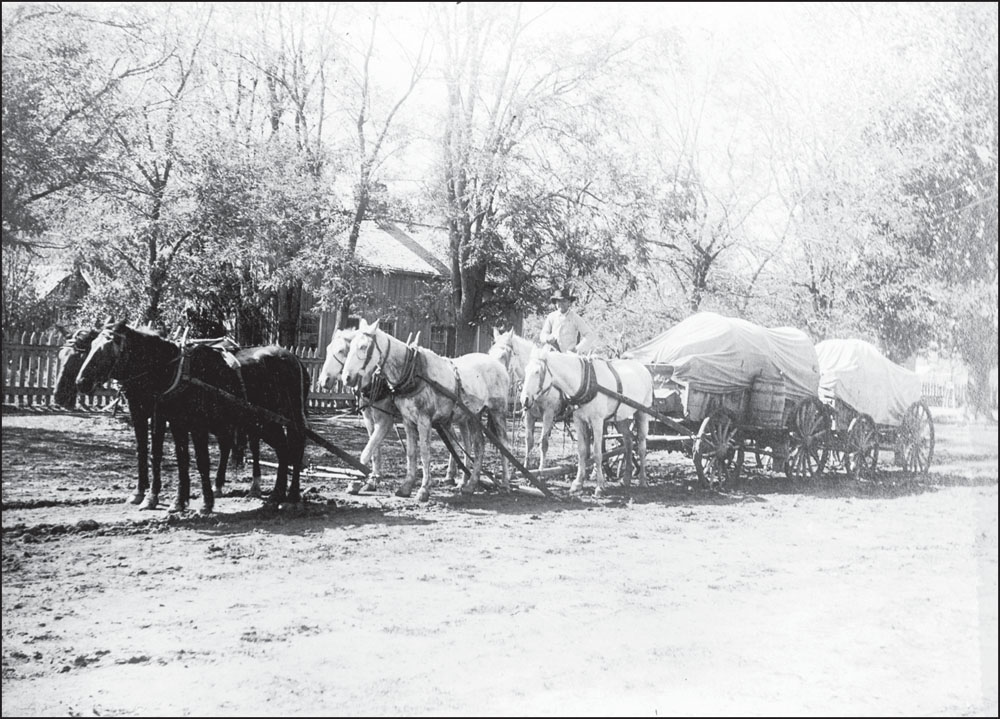

A few ranchers moved into the White Mountains in the 1870s, drawn by the government’s obligation to feed men and horses and dole out rations of beef twice a week to Apache families. When the Atlantic & Pacific Railroad was completed across northern Arizona in 1881–1882, Holbrook became a major shipping point for cattle, sheep, hides, and wool going east, and supplies, equipment, and mercantile goods coming west. The freighting business between Holbrook and Fort Apache prospered.

It was an eight-day round trip from the railhead in Holbrook to Fort Apache in good weather. Drovers earned $1 a day, the same as cowboys. In spite of bad weather, vile road conditions, wagon breakdowns, lame animals, and occasional holdups, freighters were thankful to receive payment from the government in cash, a rare commodity on the frontier. Freighters made three overnight stops, at Snowflake, Show Low, and the Murphy Ranch. There was no Pinetop until 1885.

John William “Johnny” Phipps was ranching about seven miles southeast of Fort Apache in 1881 when a small band of Apaches drove off his livestock and killed Johnny Cowden, an elderly cowboy who was staying at the ranch house. Phipps heard shots as he was coming in and hid in the brush until nightfall. He then rode to the fort, where he stayed for a few years.

In 1885, Phipps moved onto his homestead on top of the Rim. He farmed about 15 acres, built a log cabin grocery store and saloon, and freighted. The “Top of the Pines,” as the troopers called it, was a favorite watering hole for enlisted men. One often-told story claims that Pinetop was named for Walt Rigney, Phipps’s bartender, who later bought the saloon. Troopers called him “Pinetop” because he had an unruly thatch of red hair on top of his head that resembled a pine tree, or so the story goes.

Another part-time freighter was William “Billy” Scorse, an early resident of Lakeside. Scorse, an Englishman, grew hay and raised sheep on Billy Creek, which was named for him. He sold produce and canned goods, but his most profitable enterprise was his Last Chance Saloon. Scorse probably moved to Lakeside about the same time Phipps came to Pinetop.

Times were about to change. In the mid-1870s, Brigham Young, leader of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS), embarked upon a plan to colonize the Little Colorado River Valley. Colonists were asked to leave their possessions behind and establish permanent settlements in Arizona. Among the LDS colonists were William Lewis Penrod and his wife, Polly Ann Young. They left Utah in 1878 with two yoke of oxen, a team of horses, nine children, and sufficient supplies to last six months, arriving in Snowflake in 1879 in a blizzard. Penrod found work with Snowflake rancher John Henry Willis, and they lived there for a couple of years.

In 1881, Cooley hired William Penrod to build and operate a mule-powered shingle mill at Show Low. In 1886, Penrod decided to strike out on his own. He moved his family to a mountain meadow within sight of Johnny Phipps’s chimney smoke in Pinetop. The Penrods and their children lived in their wagon box until they could build a log cabin. Before long, the Penrods’ married children and grandchildren joined them, creating a community of Penrods.

In 1889, Corydon Cooley sold the ranch in Show Low to Huning and moved to a meadow a few miles south of Pinetop, on the reservation where his wife Mollie had grazing rights. He hired William Penrod to build a large, two-story house. The Cooley Ranch became a well-known stopover and forage station for freighters, military personnel, and travelers well into the next century.

Mormon colonists had established communities along the Little Colorado River and Silver Creek drainages by 1890. With freighting to supplement their farming and ranching, they became more prosperous. In the next decade, LDS pioneers looked to the mountains and the headwaters of Show Low Creek.

SHEEPHERDERS. The first stockmen in what is now the Pinetop-Lakeside area were Spanish sheepherders from New Mexico who spent summers in the mountains. Herders were itinerant, moving their flocks continually to new pastures, living in tents, and cooking in the open. Sheep ranching was highly profitable in the latter half of the 1800s, when stock could graze on the public land and wool was in demand worldwide. Many Western stockmen preferred sheep to cattle, as the profit turnover was faster. Ewes had two lambs every year, while cows only had one calf. (Courtesy Navajo County Library District.)

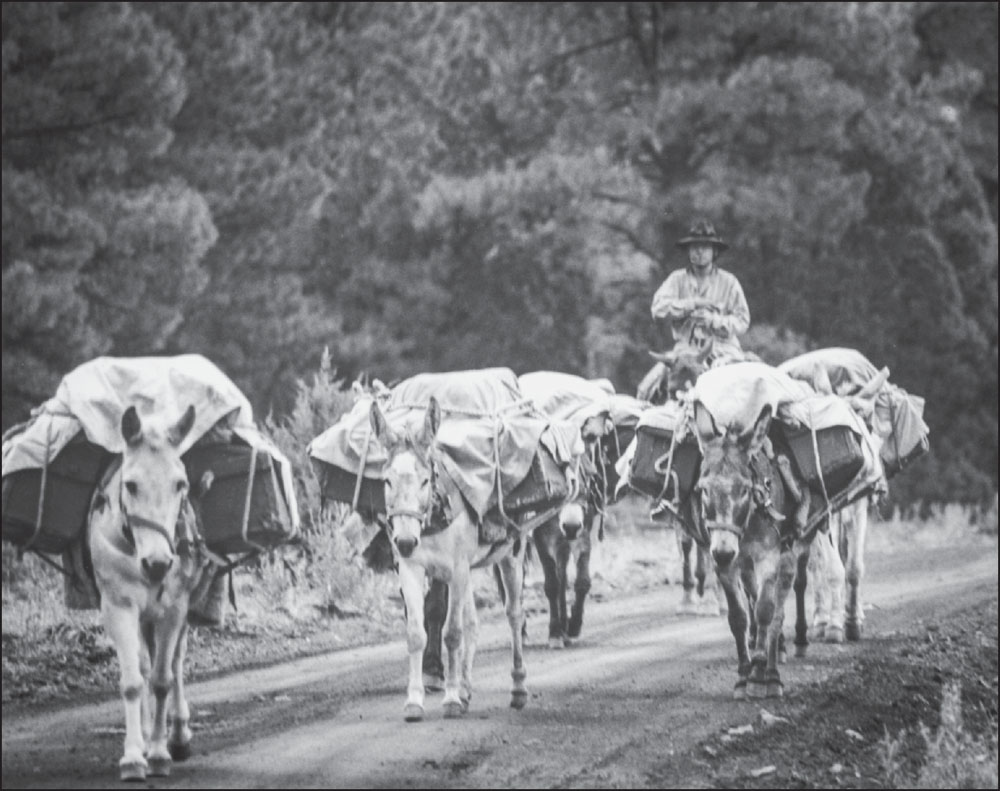

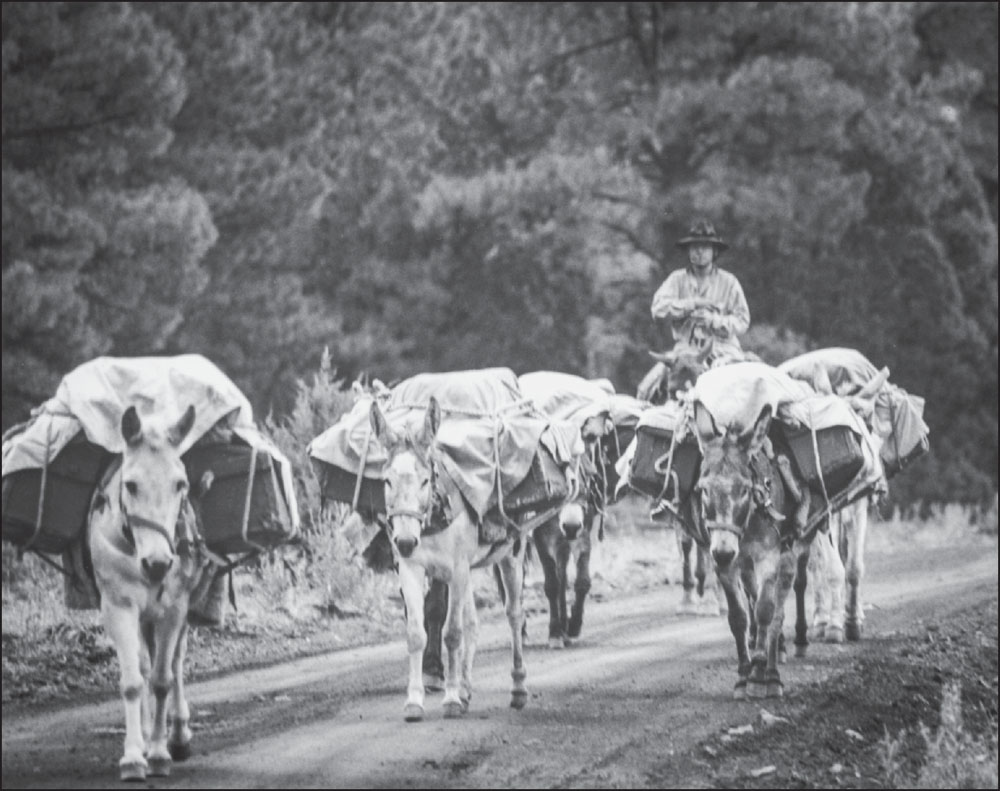

PACK BURROS. Sheep men no longer use the historic Heber-Reno Sheep Driveway to move their bands to the White Mountains in spring and back to the Salt River Valley in the fall. When the trail was in use, herders packed supplies on burros to go from one camp to the next. The cocinero went on ahead with the burros so he could prepare a meal and set up camp for the night. This photograph was taken near Los Burros, which is now a national forest campground east of Pinetop-Lakeside. (Courtesy Juliette Aylor.)

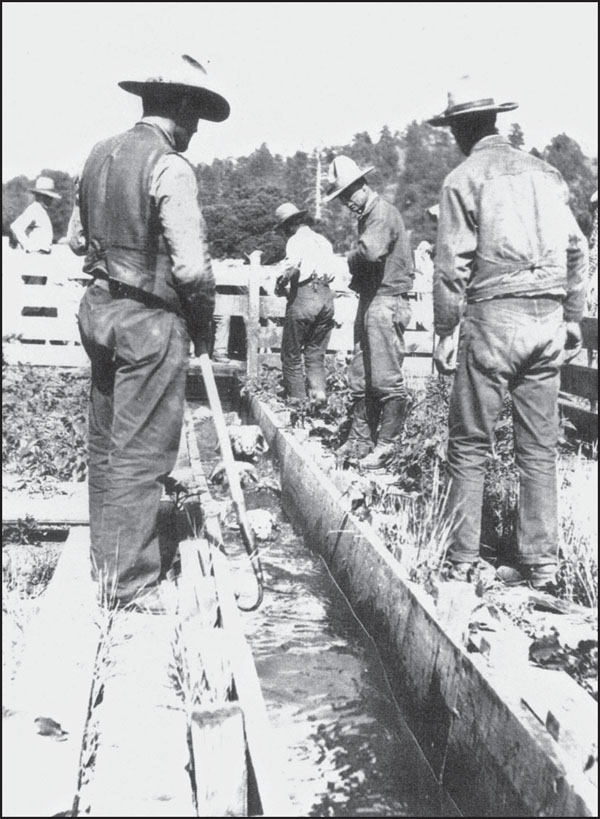

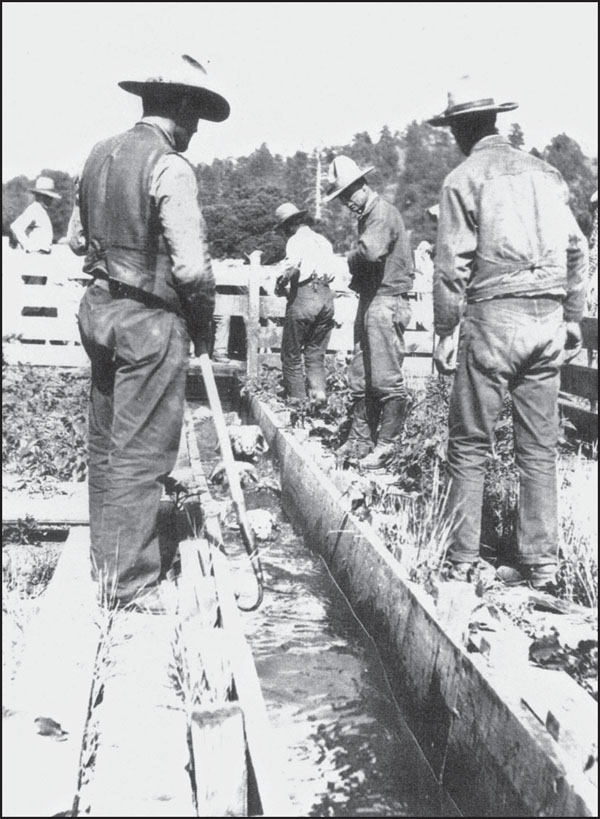

TIMBER MESA DIPPING VAT. Sheep owned by Sanford Jaques of Lakeside were dipped in vats in the summer to rid them of parasites. The sheep were driven into a tank full of water mixed with insecticides and fungicides. Men used a plunger to dip them down over their heads, and then allowed them to walk out, have a good shake, and join the band. The dip protected them from fleas, ticks, mites, and flies that carried diseases. (Courtesy Nancy Stone.)

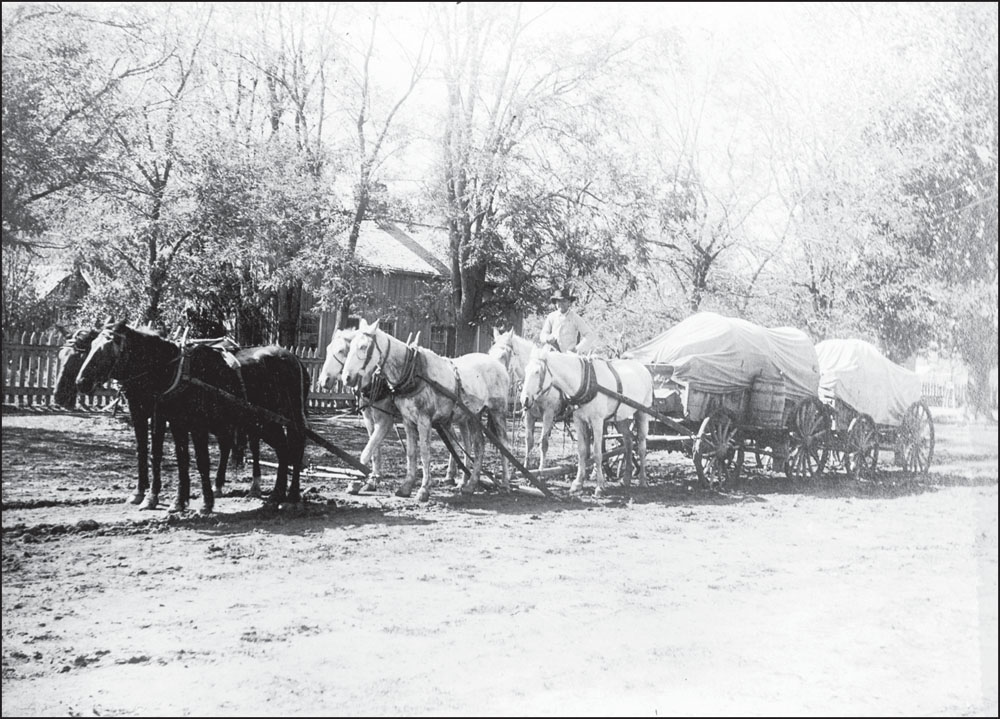

FREIGHT WAGONS AT THE RAILROAD. The Atlantic & Pacific Railroad came to Holbrook in 1881, enabling people in northeastern Arizona to ship goods out and order supplies from the East Coast. Before the railroad arrived, ranchers had to drive cattle to railroad stock pens in Magdalena, New Mexico. Sheep men shipped wool by the ton to woolen mills in the east. Merchandise, hardware, machinery, wagons, and other supplies were shipped in. Many of the early settlers made their living freighting between Holbrook and Fort Apache. (Courtesy Navajo County Library District.)

SNOWFLAKE FREIGHTERS. Some of the busiest freight outfits were in Snowflake and Taylor. They shipped hay, grain, corn, beans, sugar, and food staples to Fort Apache for the semiweekly rations provided to Apache people. They also carried household items for officers and their families, as well as mercantile supplies for the post trader. This six-horse outfit belonged to the Hunts of Snowflake. (Courtesy Al Levine.)

ARMY AMBULANCE. The fastest and most comfortable way to travel in the early days of Fort Apache was by Army ambulance coach. This mule-drawn vehicle was often used to transport Army wives and their voluminous belongings. Author Martha Summerhayes wrote a fascinating account of her journey to Fort Apache by Army ambulance in Vanished Arizona. (Courtesy Navajo County Library District.)

COOLEY RANCH, 1889. Pinetop pioneer William Penrod and his sons built this spacious home for Corydon Cooley and his wife, Mollie. It was on the main road to Fort Apache, a few miles south of Pinetop. Cooley was known for his jovial hospitality, and Mollie for her cooking and housekeeping skills. The Cooley Ranch was a stopover for travelers between Holbrook and Fort Apache. Cooley provided for man and beast, and also operated a telegraph office. Dances were frequently held for neighbors in Pinetop, Lakeside, and surrounding ranches, with music provided by the Penrod family. (Courtesy Lonnie Amos West.)

MOLLIE COOLEY FAMILY. Mollie Cooley and her children are seen here on the front porch of the Cooley ranch house in 1919. They are, clockwise from Mollie Cooley, who is sitting at the front end of the table with her back to the camera, Corydon “Don” Cooley, Cora Cooley Pettis, Emily Pettis, Charles Pettis, Roy Pettis, Elsie Amos, Roy Amos, Albert “Bert” Cooley, Belle Crook Cooley Amos, and Charles Cooley. (Courtesy Lonnie Amos West.)

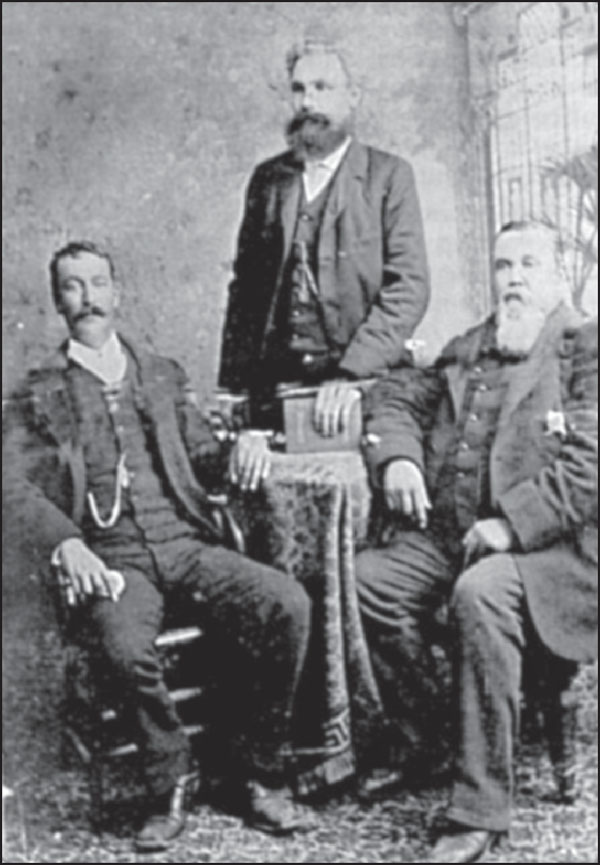

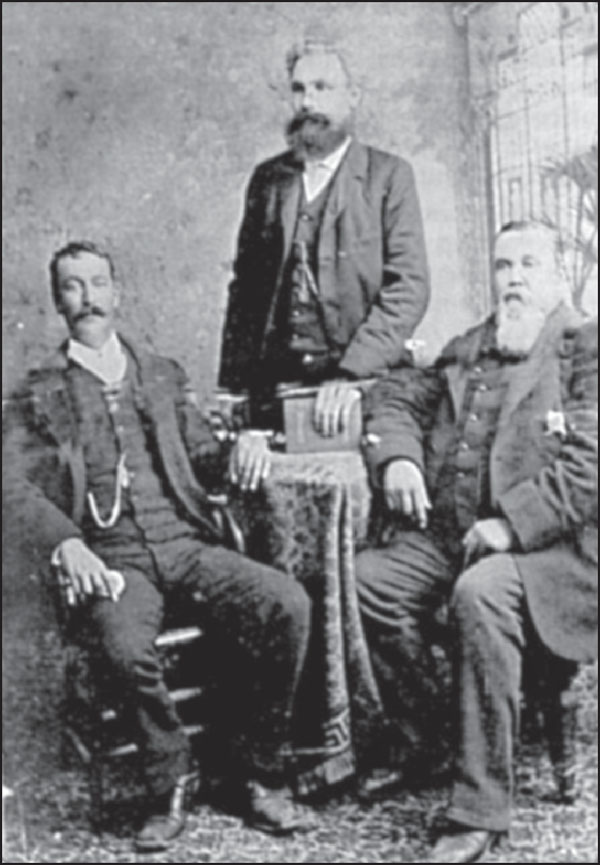

BACA, HUNING, AND COOLEY. This formal portrait of Donicio Baca, Henry Huning, and Corydon E. Cooley may have been taken in 1879 when Apache County was created out of Yavapai County. Cooley is wearing the star he received as a deputy US marshal in 1877. He was elected to the board of supervisors in the first county election. Apache County consisted of approximately 21,000 square miles. It included the White Mountains and all of present-day Navajo County. (Courtesy Show Low Historical Society Museum.)

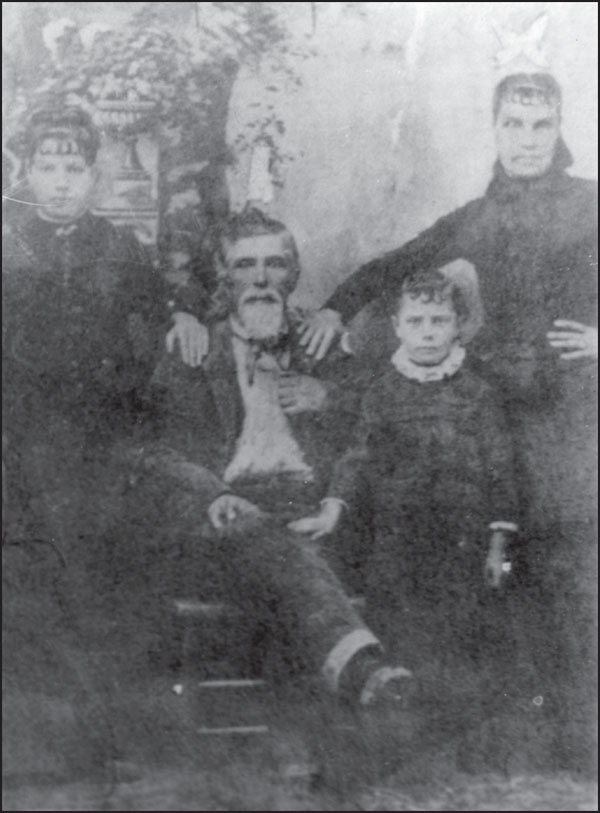

WILLIAM LEWIS PENROD. William Lewis Penrod and his wife, Polly Ann, moved to the Pinetop meadow in September 1886. Penrod was a skilled carpenter. As more settlers arrived from Utah, he and his sons never lacked for business. Historian Leora Shuck wrote that “Susan and husband with three children moved to Pinetop and made their home adjoining their father’s place. Then Bert, Del and Eph came with their wives and children. Liola, Liona (twins) and Mayzetta married and lived in Pinetop near their father. Soon he had all his children around him.” (Courtesy Navajo County Library District.)