Three

COWBOYS, SHEEPHERDERS,

AND FARMERS

Two drinking establishments prospered from the sale of liquor to soldiers from Fort Apache in the 1880s: Johnny Phipps’s saloon on “Top of the Pines” and Billy Scorse’s Last Chance Saloon, in what is now Lakeside. Drunken brawls were common in Pinetop, especially when soldiers from Fort Apache rode into town.

Enlisted men may have misbehaved at the bar, but local residents seldom complained. Fort Apache continued to be the major source of cash income for both settlers and Apaches. In the 1890s, the post was a proper community, with a school, a hospital, and a library.

Settlers on top of the Rim had none of the luxuries enjoyed by the military. James R. Jennings wrote of a freighting trip to Fort Apache with his father in 1898: “Homes of officers were the ultimate in fine living and elegance . . . The Morgan bred cavalry horses were a sight to behold! The horse barns were always freshly painted and immaculately clean.”

Pinetop went through several name changes, including Penrodville and Malpai, referring to the pervasive volcanic rock that made every effort of man and beast difficult. In 1891, the post office was officially named Pinetop, with Edward E. Bradshaw appointed postmaster. There was a one-room store run by a profane bullwhacker named McCoy, a small sawmill, a dance hall, and a saloon.

William Lewis Penrod and his wife, Polly Ann, had 12 children. The Penrods were a lively, hardworking, fun-loving family, each with special abilities. Lakeside historian Leora Schuck wrote, “William Penrod loved sports. He could ride, he could rope, he could take a joke and give one, and he loved music and dancing.” His sons John Ralph, Thell, and Arch played the fiddle.

Another early Pinetop settler, John Washington Adair, rode boldly into town in 1895 at the age of 20. He intended to take care of some business, stay overnight, and leave early the next morning. His plans changed, however, when he met Cynthia Jane, the 16-year-old daughter of David Israel Penrod. They were married in Adair’s hometown of Kanab, Utah, and returned to live in Pinetop, near her parents and grandparents, where they stayed for the rest of their lives.

Hans Hansen Sr. and his wife, Mary Adsersen, both natives of Denmark, paid Joseph Stock 20 head of cattle for “squatter’s rights” to his land and cabin in the little settlement originally called Fairview. Some called it “Hog Town” because of Al Young’s hogs, which ran wild in the woods. Latter-day Saints president Jesse M. Smith named the place, more appropriately, Woodland.

The Hansen men were master masons and bricklayers. One day in 1903, Hans and his son Niels stopped at Will Amos’s sheep ranch on their way to work at Fort Apache. Amos commissioned them to build an adobe house for his family. Two years later, Niels Hansen bought the house back when Amos decided to move on.

Will Amos’s younger brother Abraham Lincoln “Abe” Amos, continued to raise sheep, as his wife had grazing rights on the reservation. He was married to Belle Crook Cooley, one of Corydon Cooley’s daughters. Another pioneer settler, Samuel “Ezra” West, and his wife, Julia Ellsworth West, had a son named Earl who married Elsie Amos, the daughter of Abe and Belle Cooley Amos. Intermarriage strengthened the bonds between early settlers.

Pioneer life in Pinetop and Lakeside was one of endless work, but also one of large, close-knit extended families that helped one another. At an elevation of more than 7,000 feet, winters were severe and growing seasons short. Worse, the soil was thin and rocky. Pure spring water and wood for building and heating were plentiful, but rain was unpredictable, so gardens and farms were irrigated from creeks.

Pioneer families ate what they raised, caught, or shot. They kept chickens, sheep, cattle, goats, and hogs, and most had a milk cow. From the earliest age, children were given chores such as gathering eggs, feeding livestock, milking cows, churning butter, hauling water in buckets, and weeding gardens. Boys and some girls learned to ride and shoot almost as soon as they could walk.

Mountain families relied on game and fish to supplement their diet. There were no natural lakes, but trout thrived in the streams. Elk, deer, and wild turkeys were nearly on their doorstep. Large predators like mountain lions, wolves, and black bears took domestic animals at times, but they preyed largely on game. In late summer, women and children gathered wild grapes and raspberries for jam and jelly. Potatoes, turnips, and carrots were preserved all winter in dugouts.

One especially hard winter, the William Penrod family had to feed their corn-husk mattresses to the livestock and sleep in the hayloft. In summer, the Penrod men drove wagons to mountain meadows and cut wild hay for the winter, stopping to hunt on the way home.

In spite of the hardships endured by settlers, romance was always in the air. Marcena Hansen had more on her mind than preserving turnips. Liona “Owen” Penrod escorted her to a Thanksgiving ball at Penrod’s dance hall in 1900. To impress her, he drove up in a black buggy pulled by two “shining black horses.” She wrote, “He was dressed fit to be a prince for this eventful night.” He proposed on the way home.

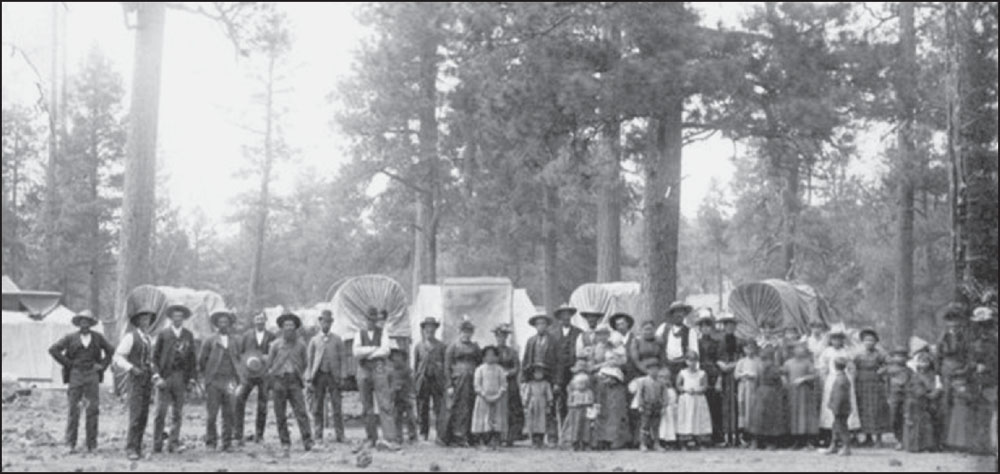

PINETOP CONFERENCE. In 1892, Pinetop hosted a conference for members and leaders of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Four Arizona stakes (divisions of the church) were represented: Snowflake, St. Johns, Maricopa, and St. Joseph. More than 1,100 members of the LDS church attended. Meetings focused on problems of land ownership resulting from loans by the church to colonists who came to Arizona Territory. A solution was reached when the LDS Church authorized members to reimburse the church through labor on dams and irrigation canals. Pinetop and Lakeside settlers built a large pavilion for dancing. Church leaders allowed only square dancing during the conference. When they left, it is rumored that local church members stayed up all night “round dancing” under the pines. (Courtesy Snowflake Heritage Foundation.)

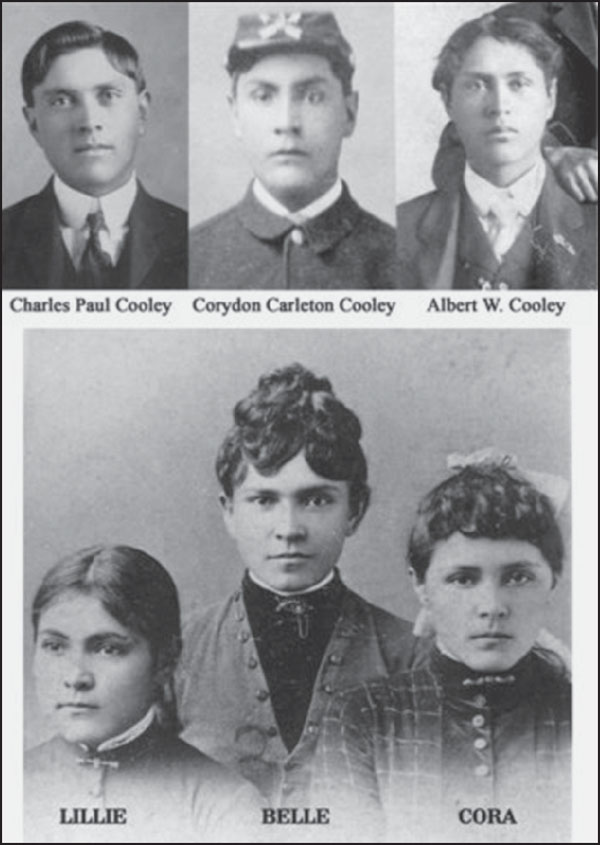

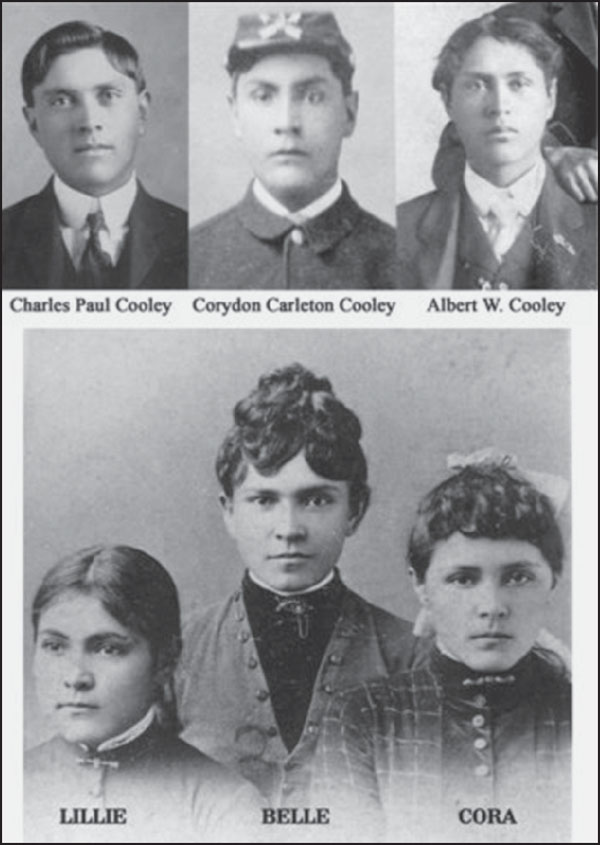

CHILDREN OF CORYDON AND MOLLIE COOLEY. In later years, Corydon Cooley was generally called “Colonel Cooley,” a term of respect rather than a military title. Cooley held public offices and continued to serve the military at Fort Apache when called. He and Mollie had five children, all of whom were well educated. Their boys were Charles Paul, Corydon Carleton, and Albert. The girls were Belle and Cora. Lillie was the daughter of Corydon’s wife Cora, who died in 1876 of complications following childbirth. (Courtesy Lonnie Amos West.)

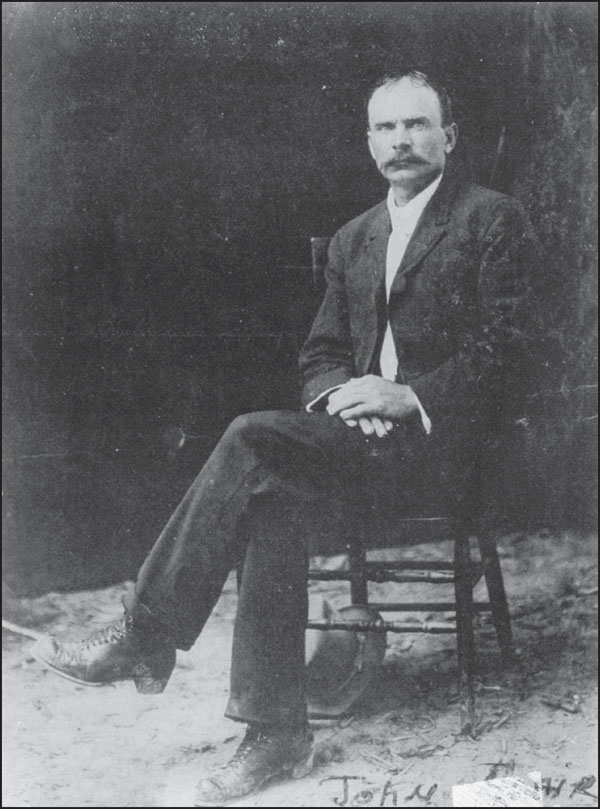

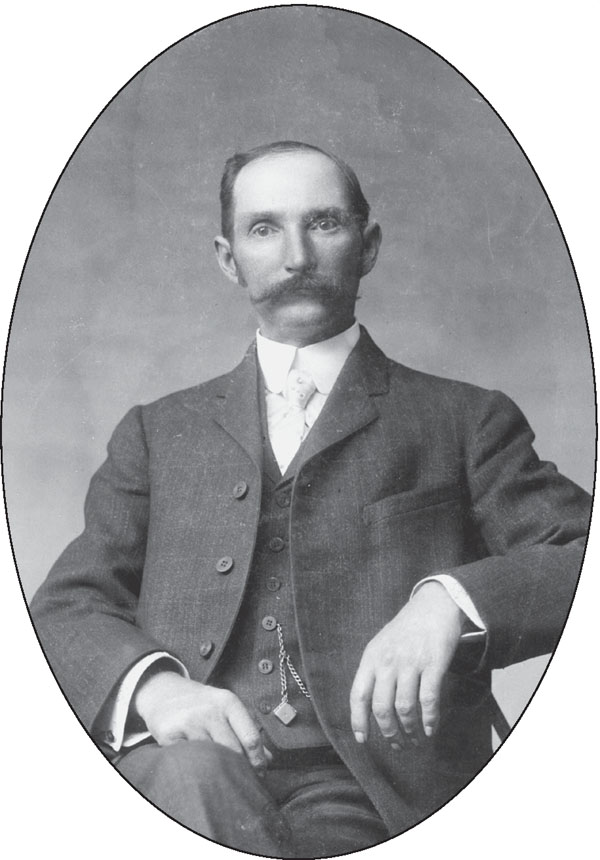

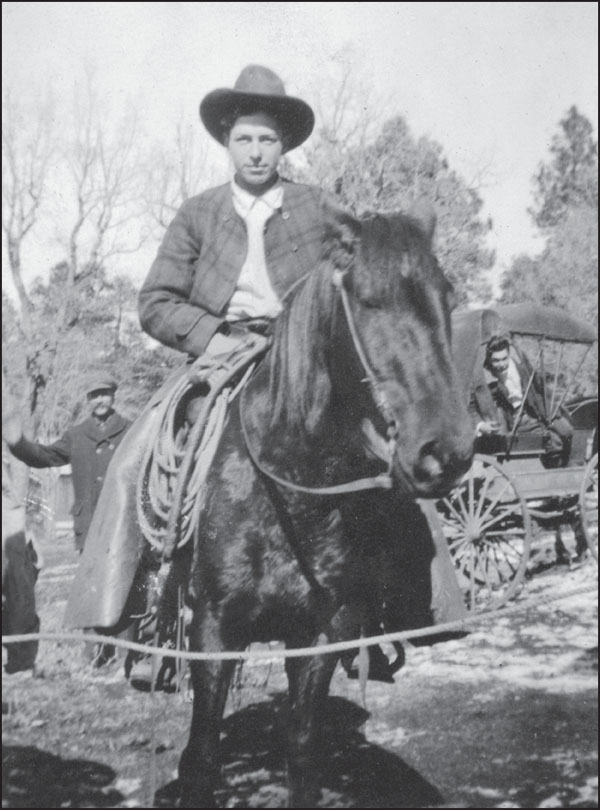

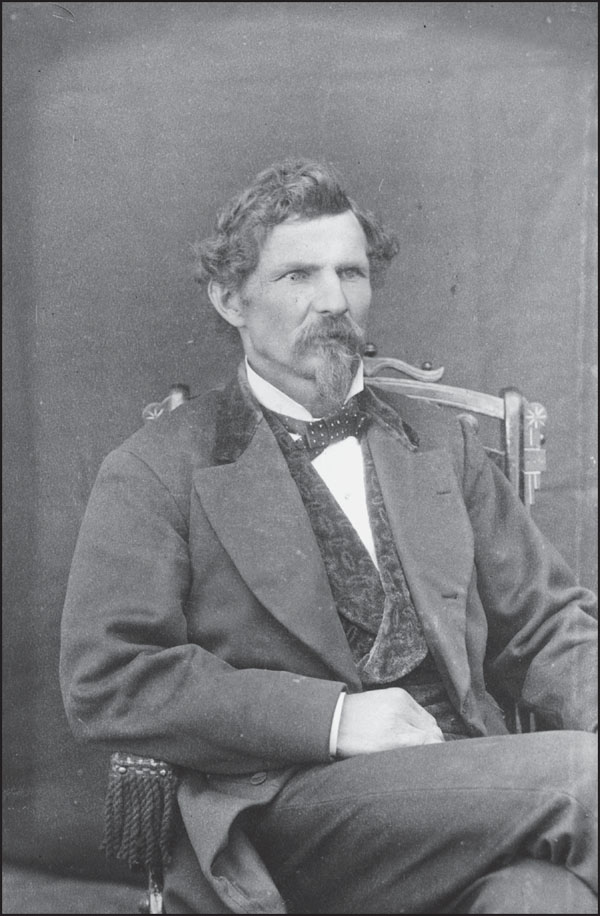

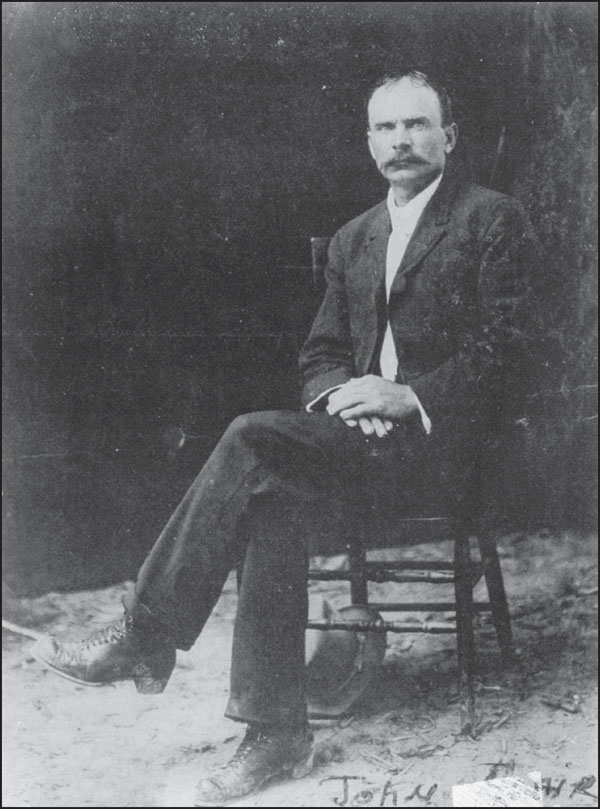

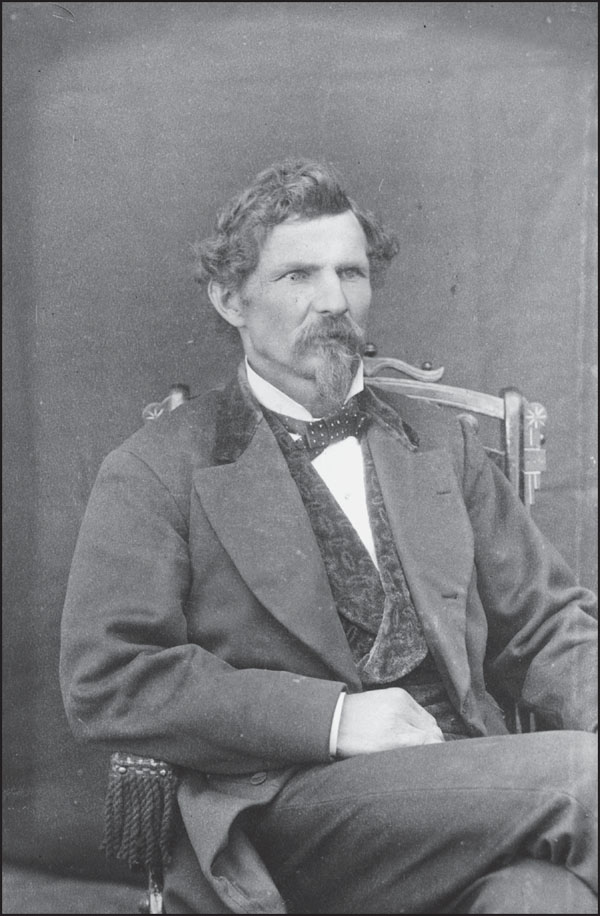

JOHN WASHINGTON ADAIR. One of Pinetop’s first residents, Adair arrived in Pinetop in 1894 at age 20 and married 16-year-old Cynthia Jane Penrod, the daughter of David Israel Penrod and granddaughter of William Lewis Penrod. (Courtesy Bobbie Stephens Hunt.)

GEORGE AND HARRIET STEPHENS. These early Pinetop residents are seen here on their wedding day in 1907. (Courtesy Lonnie Amos West.)

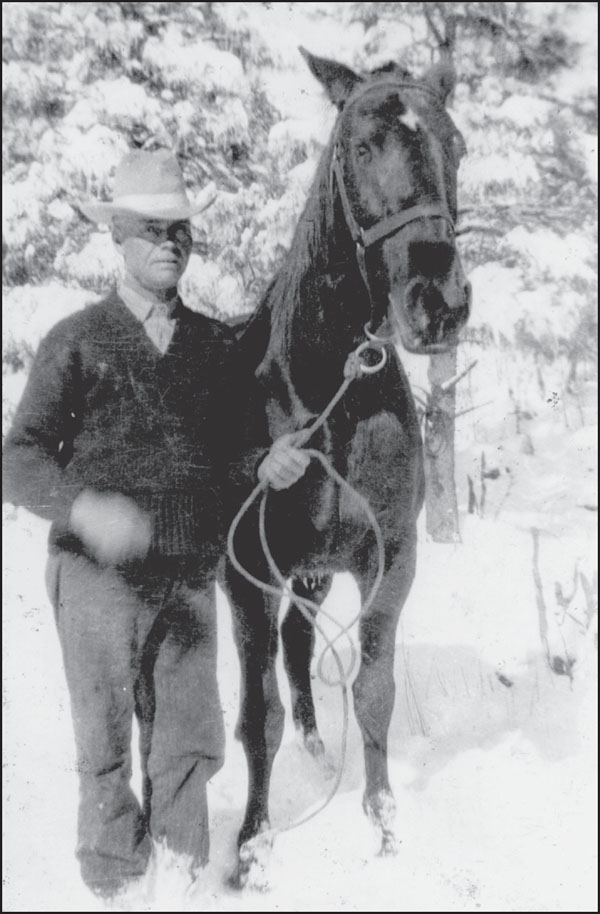

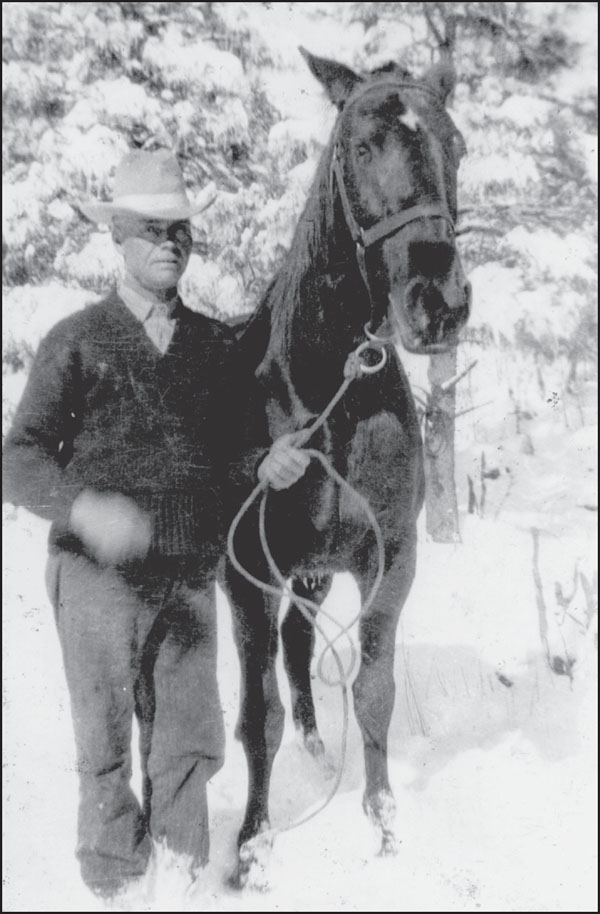

GEORGE STEPHENS AND HIS HORSE FRED. George Stephens hauled freight to Fort Apache, usually accompanied by his wife, Harriet. Their son George Stanley Stephens was born in a wagon in 1909 on the road between Pinetop and Fort Apache. (Courtesy Bobbie Stephens Hunt.)

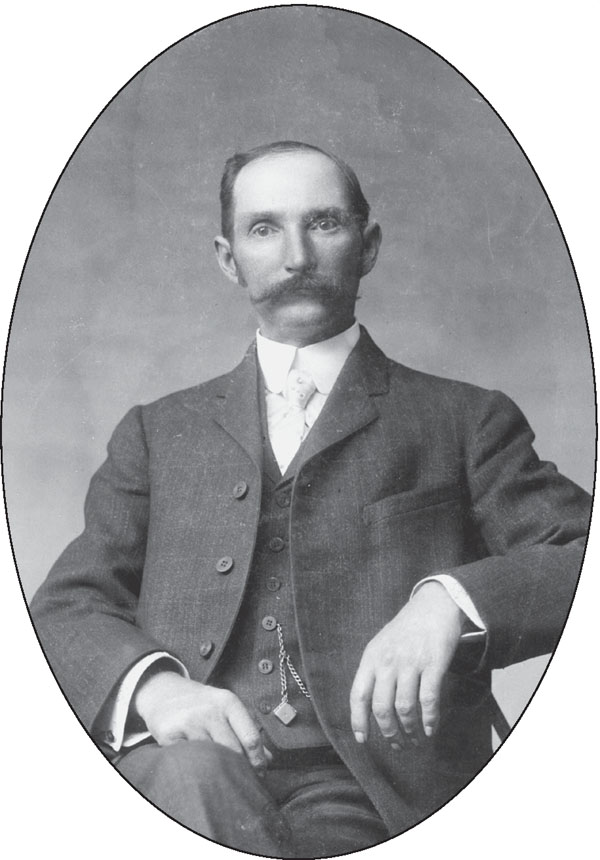

WILL AMOS. The eldest son of Milton and Alphidus “Allie” Amos, Will Amos came to Arizona in 1886. Milton died in Holbrook, but Allie and her children, George, Dick, Abe, Len, Della, and Will, homesteaded in what is now Lakeside. Will Amos had the first house in Lakeside, built by Hans and Niels Hansen. In 1905, Niels Hansen actually bought the house from Will when the wool market collapsed. The house is still standing near Rainbow Lake. (Courtesy Lonnie Amos West.)

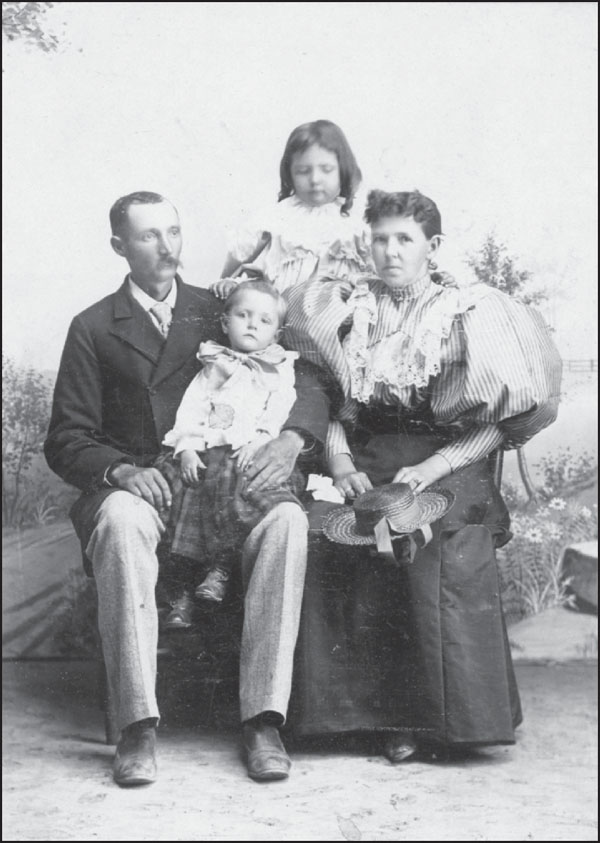

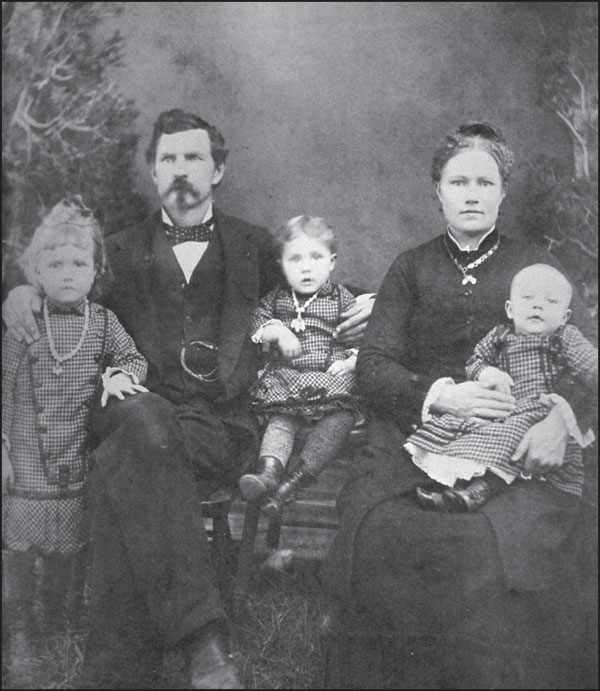

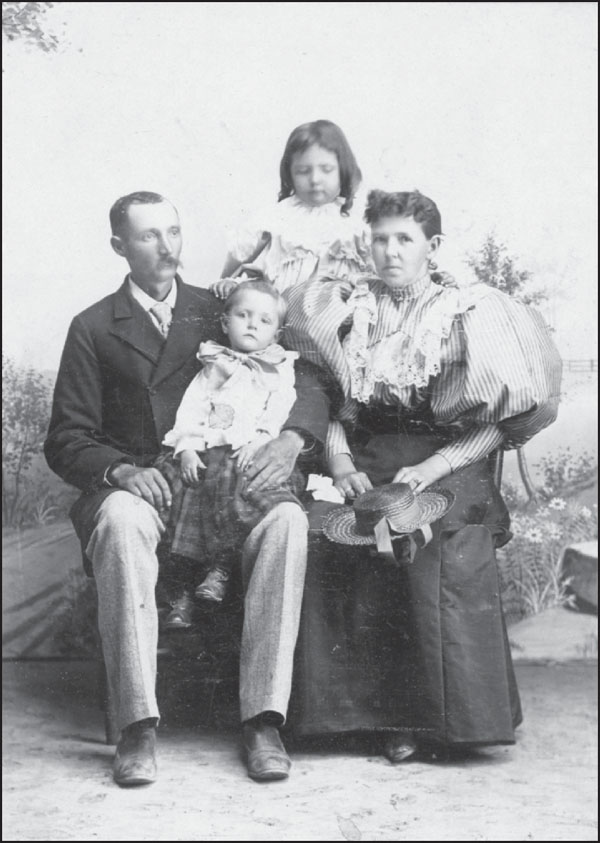

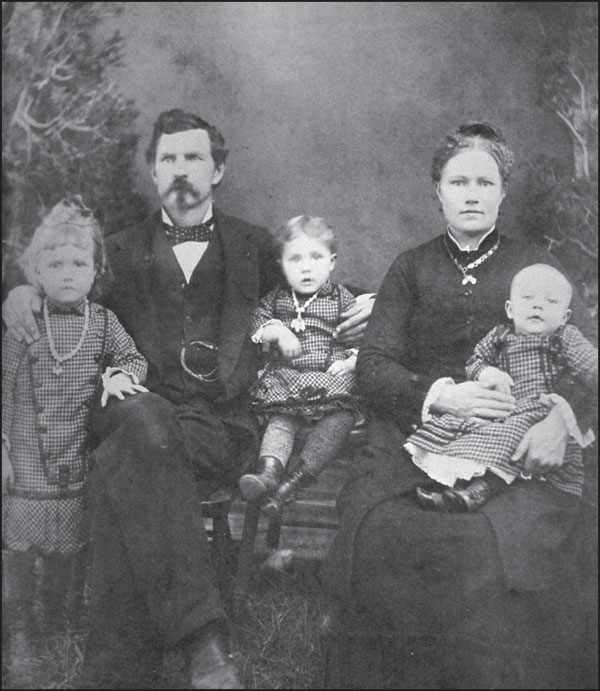

WILL AMOS AND FAMILY. William Nathaniel “Will” Amos, his wife, Carrie, and two of their children are seen here. Will bought land and sheep from men named Kinder and Adamson and settled in Lakeside with his wife. The couple had three children while in Lakeside: Pearl, Willie, and Harley. Will was highly respected as a successful rancher and a good businessman. He and his family left Lakeside in 1905. (Courtesy Lonnie Amos West.)

ABE AMOS. Abraham Lincoln “Abe” Amos was a younger brother of Will Amos. His siblings left the White Mountains, but Abe stayed in the sheep business. His wife, Belle, the daughter of Corydon E. Cooley and Mollie, had grazing rights on the Fort Apache Reservation. (Courtesy Lonnie Amos West.)

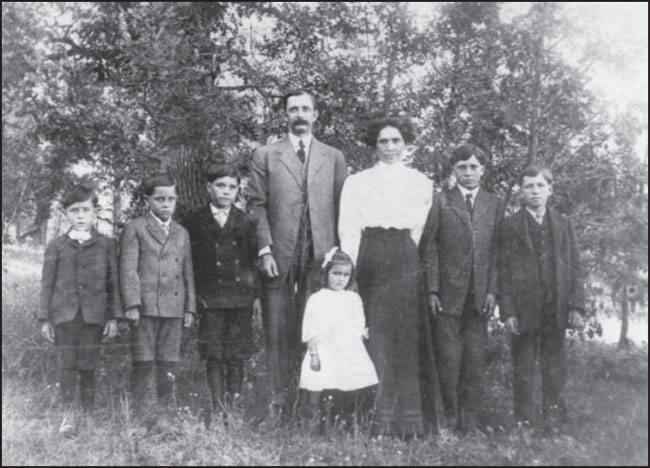

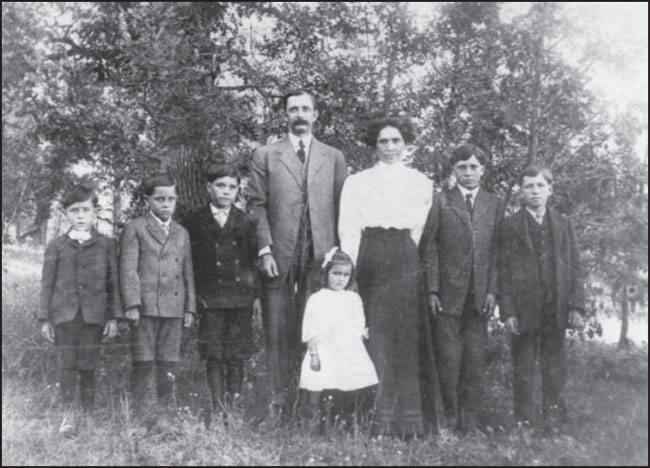

ABE AMOS FAMILY. Abe and Belle Amos made their primary home at what was called the Rock House, on the Fort Apache Reservation between the Cooley Ranch and the Big Spring (located under the Rim; not to be confused with Big Springs in Lakeside). This family photograph was taken in 1909 near the Rock House. From left to right are Tom, Earl, Byde, Abe, Elsie, Belle, Roy, and Paul. Jack and baby George are not shown. (Courtesy Lonnie Amos West.)

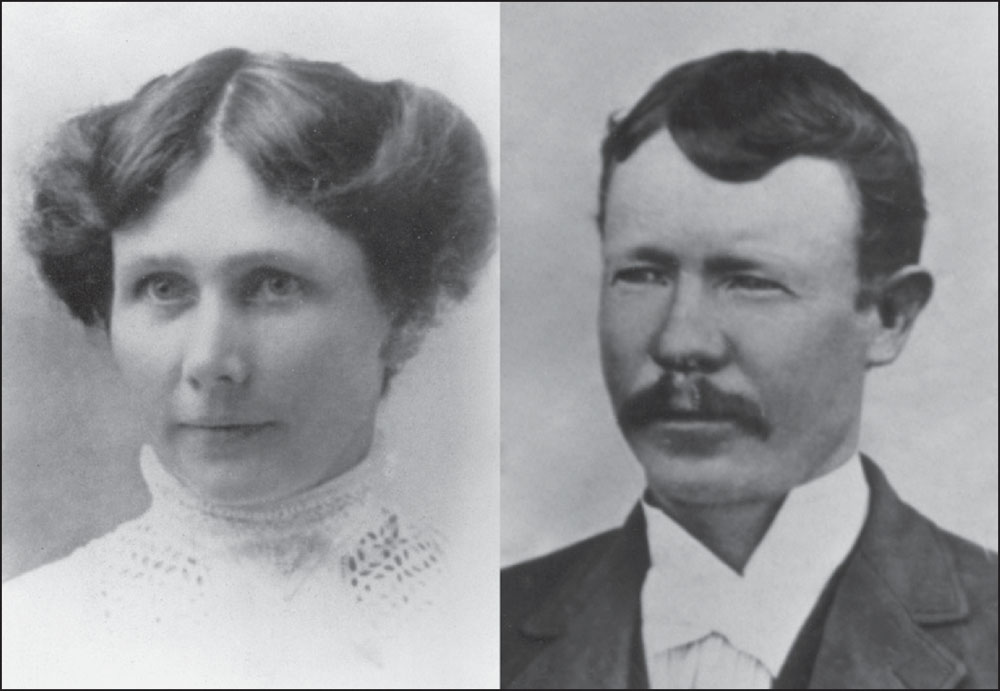

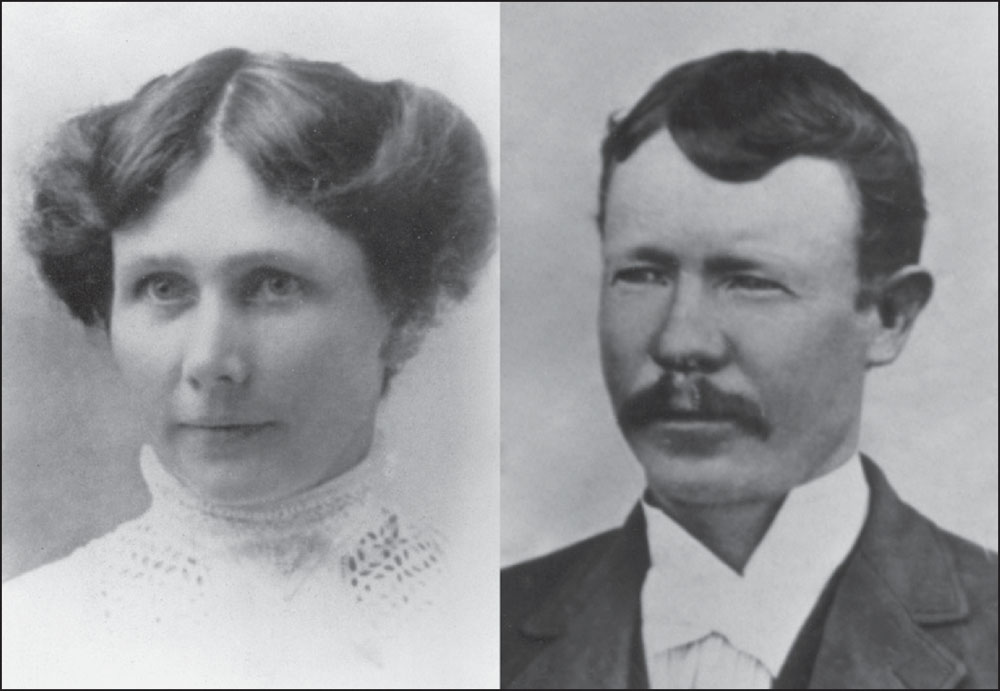

EZRA AND JULIA WEST. Samuel Ezra West and Julia Ellsworth West were married in the LDS temple in St. George, Utah, in 1886. Ezra went into the sheep business, and had a memorable encounter with the Apache Kid and another Apache while he was out in sheep camp in the mountains. The Kid had a price on his head, but Ezra fed them and dressed the Kid’s wound, asking no questions. When the wound had healed, the Kid gave him a beautiful pair of beaded moccasins before leaving. (Courtesy Lonnie Amos West.)

EZRA WEST FAMILY. In 1896, Ezra and Julia West moved their family to Woodland, where Ezra had purchased 160 acres from Abe Amos. They began farming and raised a family of nine children. Julia wrote, “We all helped to clear the stumps, trees and rocks from the land and it is a very good ranch.” Julia taught her children to take responsibilities on the farm and at home while their father was away in sheep camp. This photograph was taken in 1909. From left to right are (seated) Mary, Ezra, Julia, and Gwen; (standing) Earl, Emma, Karl, Sedena “Dena,” Joe, Ida, and Lavern. (Courtesy Lonnie Amos West.)

AMOS BOYS. These tough-looking cowboys grew up in the mountains. Pictured at the Cooley Ranch about 1908 are, from left to right, Albert “Bert” Cooley, Roy Amos, Paul Amos, and Charlie Pettis. Sitting in front is Byde Amos. Bert was the son of Corydon and Mollie. Roy, Paul, and Byde were Abe Amos’s sons and Cooley’s grandsons. Charlie Pettis was married to Corydon and Mollie’s daughter Cora. (Courtesy Lonnie Amos West.)

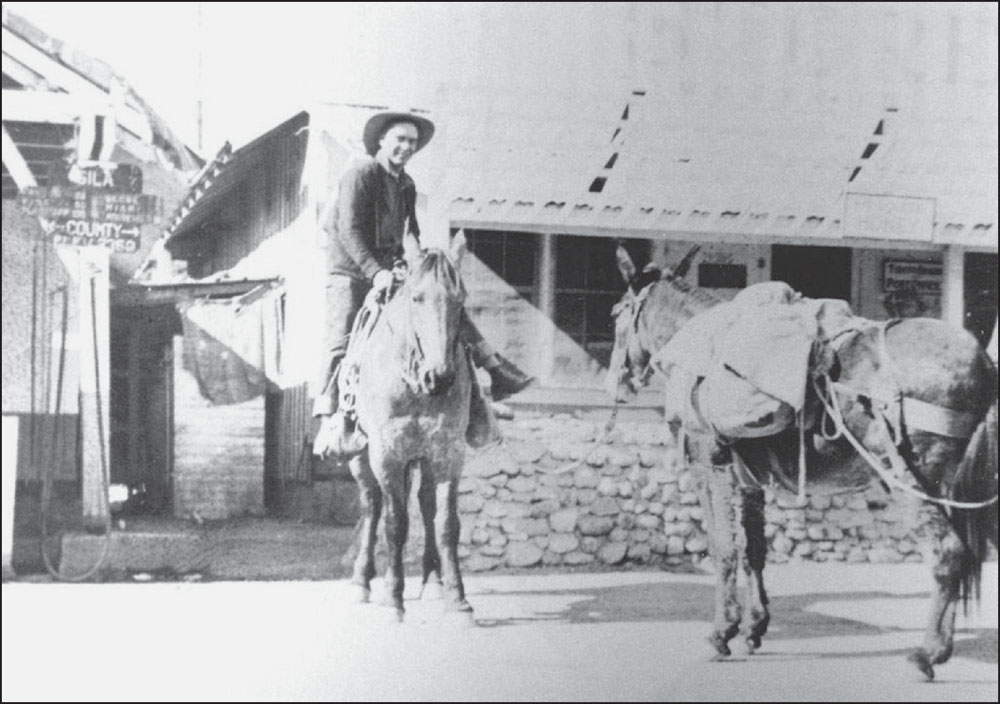

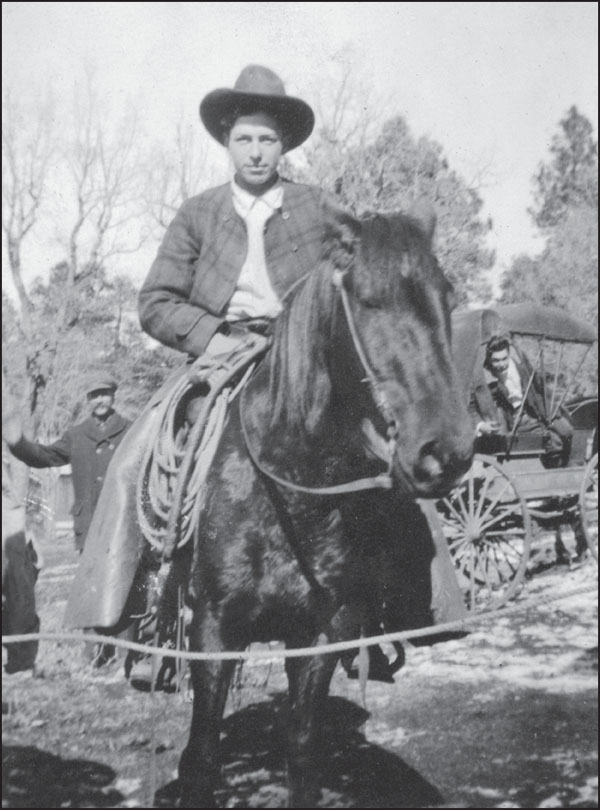

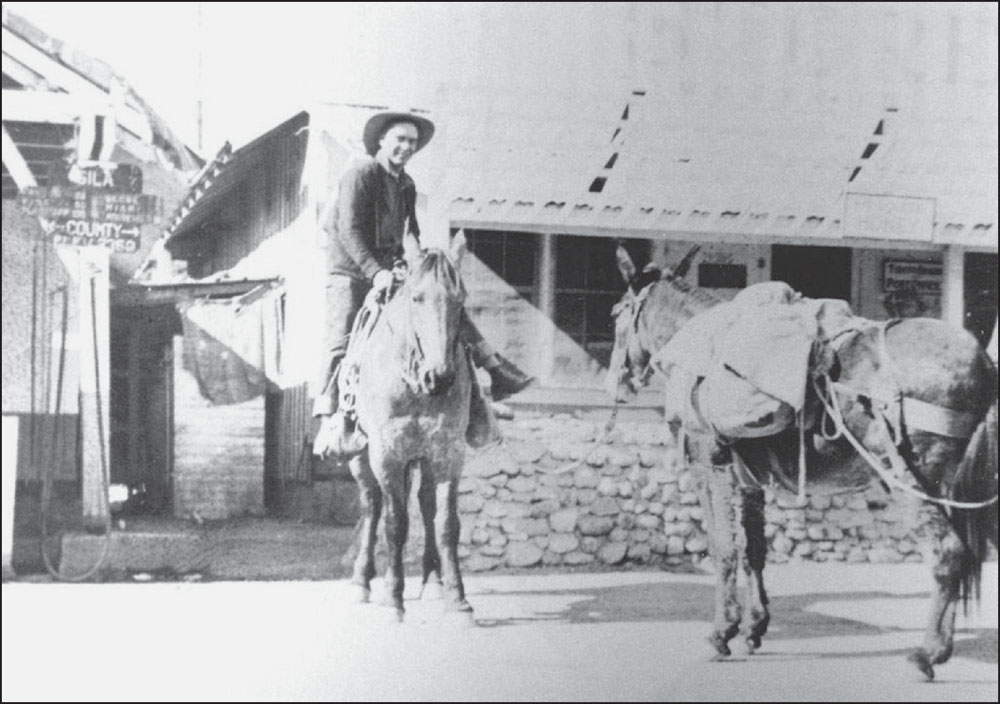

TOM AMOS. Abe and Belle Amos’s son Tom is seen here in Lakeside. All the Amos boys were good cowboys. Thomas Lavern “Tom” Amos married Elizabeth “Lizzie” Brown, and they had 11 children. (Courtesy Lonnie Amos West.)

ROY AMOS. Roy was the oldest child of Abe and Belle Amos. Following in his father’s footsteps, he became a sheep man. When he was young, he fell in love with a girl who turned him down. He never married, although he had many friends. In the winter of 1939, he was staying alone at Wilbur’s sheep camp near Heber and ran out of supplies. Attempting to walk out, he was caught in a big snowstorm. Sheepherders found his frozen body when they returned to the mountains in the spring. He was 44. (Courtesy Lonnie Amos West.)

BYDE AMOS. Byron “Byde” William Amos is seen here in batwing chaps putting a rein on a good, stout Buckskin horse about 1920. As a young boy, Byde rode bareback to chase wild horses with his father, Abe, for days at a time. Later, he rode a horse six miles to school in Pinetop every day. As a young cowboy, he was handsome and a good dancer—Bertie Merrill claimed she had danced 100 miles with him. When he was working near Heber, he often rode halfway to Holbrook, where his girlfriend, Maud Gibbons Hanson, taught school at Dry Lake. Byde and Maud were married in 1922 and raised seven children. (Courtesy Lonnie Amos West.)

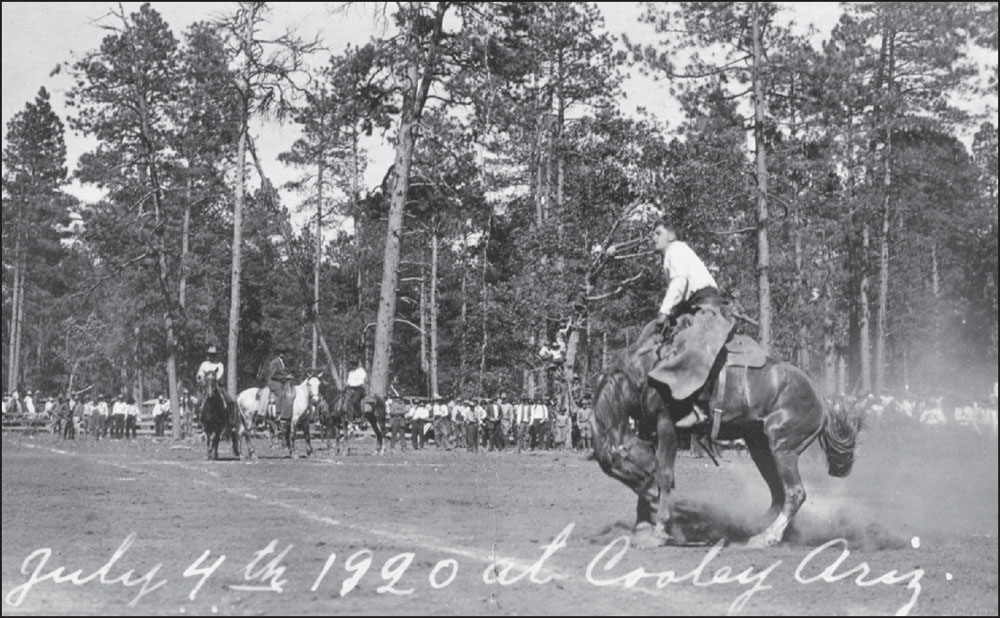

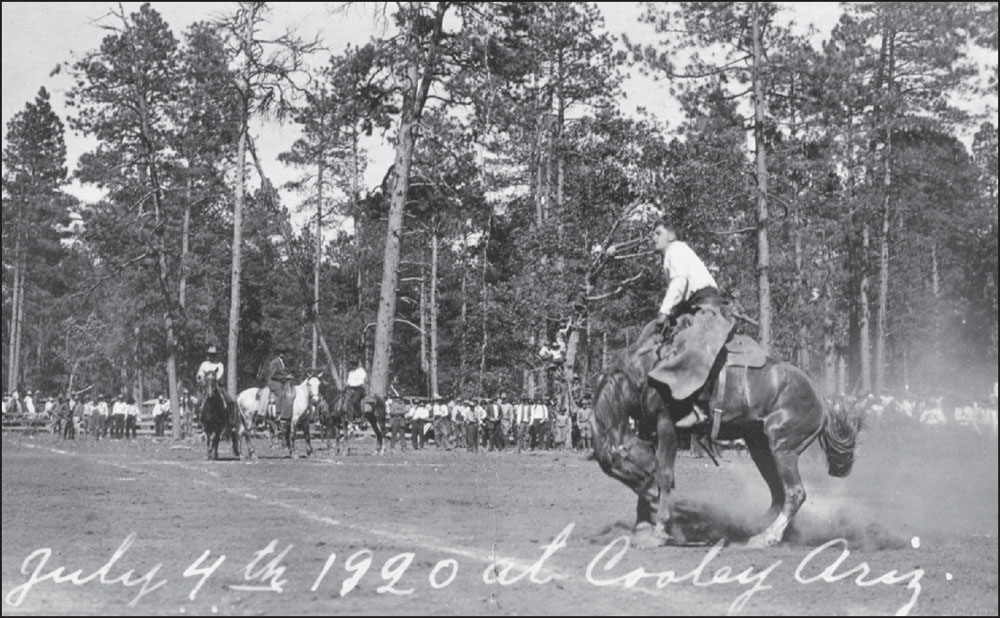

EARL AMOS. Cowboys described Earl Logan Amos as “a hell of a bronc rider.” His best friend was Earl West, the son of Ezra and Julia West. The boys were swimming in Rainbow Lake one day when they were about 19. Earl Amos had a cramp and started to go under. Earl West swam to help him but was pulled under by his friend’s frantic struggling. He managed to break free and made it to the surface, but Earl Amos drowned. Earl West never got over the tragedy, according to his family. He talked about his friend and tended to his grave for the rest of his life. Earl West was married to Earl Amos’s sister Elsie. (Courtesy Lonnie Amos West.)

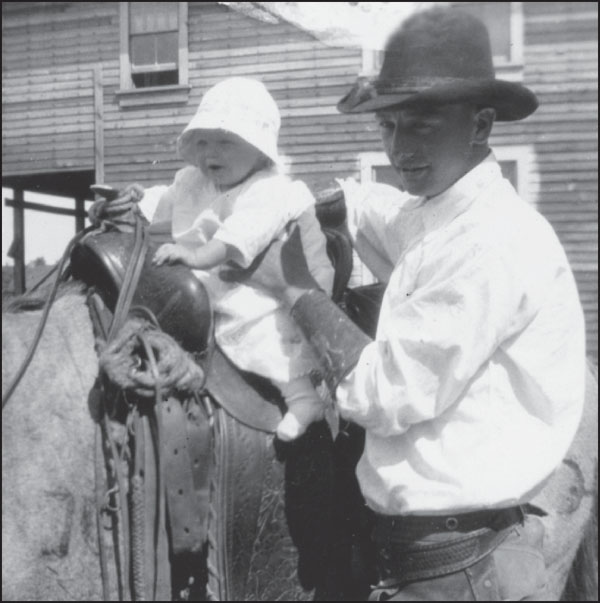

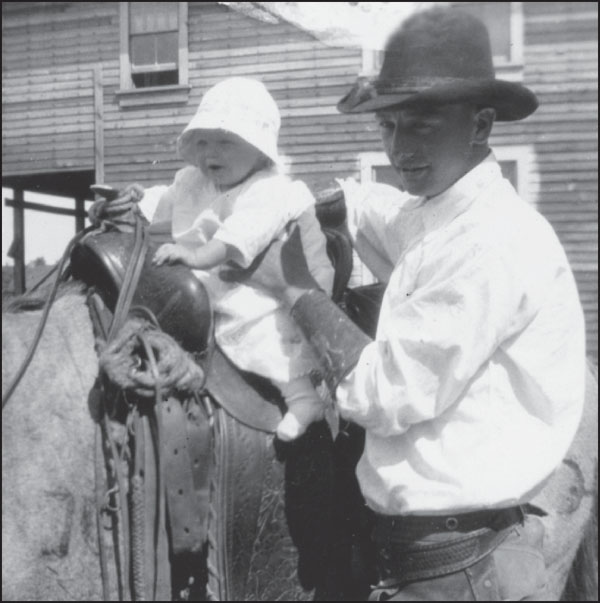

EARL WEST AND DAUGHTER JUNE. Earl West’s daughter June seems to be on track to be a cowgirl in this image. He is introducing her to his horse in front of the West Hotel, in Lakeside. Earl loved horses all his life. When he was nine, his parents let him drive a team by himself 60 miles to Holbrook for supplies. He slept out four nights. Too small to remove the collars on the big horses, he just took off the harnesses and back bands for the night and fed them. Men from the mercantile store in Holbrook loaded the wagon for him. As a man, Earl rounded up wild horses and broke them for the big cattle companies. He was also a rodeo bronc rider. (Courtesy Lonnie Amos West.)

JUNE WEST AND BELLE COOLEY AMOS. June holds hands with her grandmother Belle Crook Cooley Amos. Belle’s father, Corydon E. Cooley, gave her the middle name of Crook to honor his old friend Gen. George Crook. The name embarrassed Belle, and she told people her middle name was Lucille. She received a good education at a boarding school in Santa Fe and was an accomplished organist. Like her mother, Mollie, she was a gracious hostess, excellent cook, and hard worker. She lived most of her married life alone with her children on the ranch. A family member said, “She was always good-natured and seemed to have a happy disposition no matter what hardships she faced.” In 1935, after 44 years of marriage, Abe and Belle divorced. She went to live with her daughter Elsie and died in Glendale in 1966 at the age of 92. (Courtesy Lonnie Amos West.)

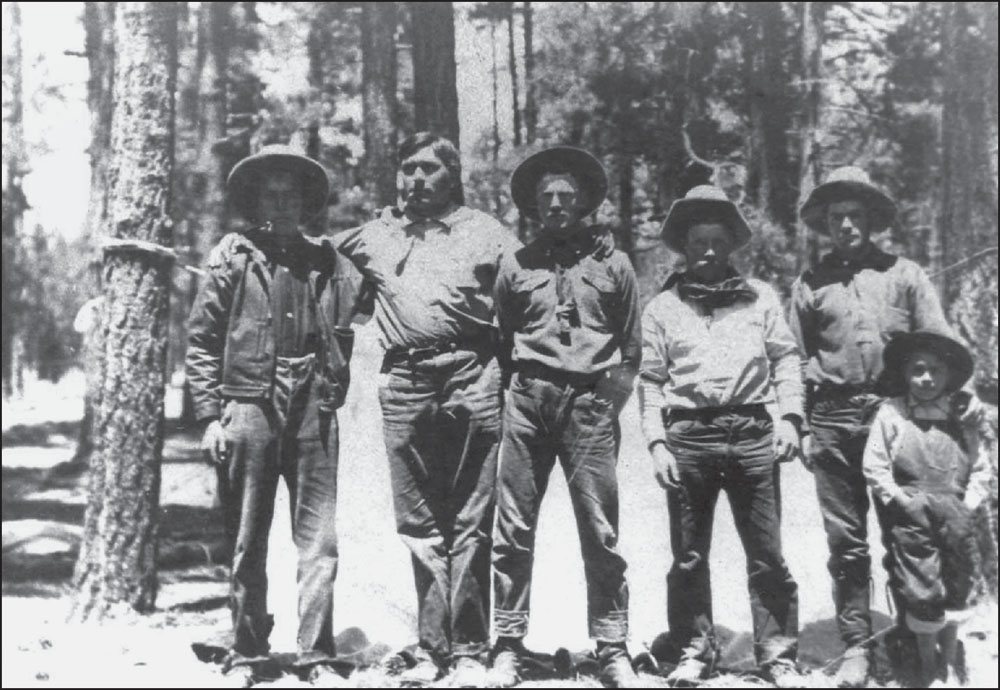

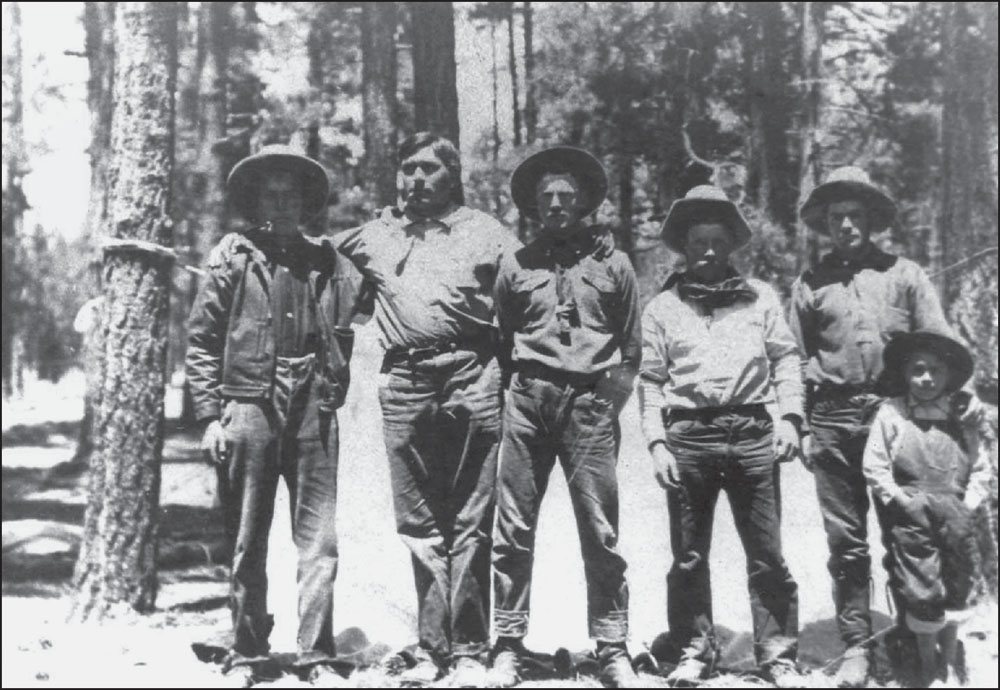

COOLEY’S “HIRED HANDS.” Having friends and relatives comes in handy at roundup time, when ranchers helped each other. Here, Corydon Cooley’s cowboys are, from left to right, Roy Amos, Charlie Cooley, a man named McBride, Charlie Faught, Charlie Pettis, and “Diddy” Pettis. (Courtesy Navajo County Library District.)

SANFORD JAQUES. Anna Christina Hansen married Sanford Jaques in 1879 in Utah. Jaques was a carpenter and building contractor. He died in 1888 in Tempe, leaving Anna Christina with four small children to support, including Sanford Warren “Santie,” “Taddie,” and Hans Logan. The widowed Anna Christina moved back to her home in Show Low and married rancher Robert Scott in 1898. They had two children, Hazel and Robert Jr. Anna Christina died in Mesa in 1940. (Courtesy Anne Snoddy-Suguitan.)

SANFORD JAQUES FAMILY. Seen here from left to right are Anna Christine “Taddie,” Sanford, Sarah Jane, Anna Christina, and Sanford “Santie.” (Courtesy Anne Snoddy-Suguitan.)

JAQUES RANCH HOUSE. In 1913, “Sant” Jaques married Beulah Whittamore Jackson, the daughter of a wealthy Kansas City cattle feeder who had acquired the former Jim Porter Ranch in a divorce settlement. Historian Leora Schuck wrote that the house was painted red, with white pillars supporting the front porches. “The great house could be seen looming through sparse trees two miles away, and Lakesiders took pride in pointing it out to visiting friends,” she wrote. Sant Jaques ran cattle and sheep on the public domain and reservation. Their Broken Arrow–brand cattle ranged from the White Mountains south of McNary to Cibecue Creek. The ranch was eventually sold to cattleman Maurice Smith. All the buildings burned down in 1953. The 80 acres around the house became part of the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forests in a 1986 land exchange. (Courtesy Myrna Hansen.)

PINETOP POST OFFICE. In 1891, the post office was officially named Pinetop, and Edward E. Bradshaw was appointed postmaster. (Courtesy Sue Penrod.)

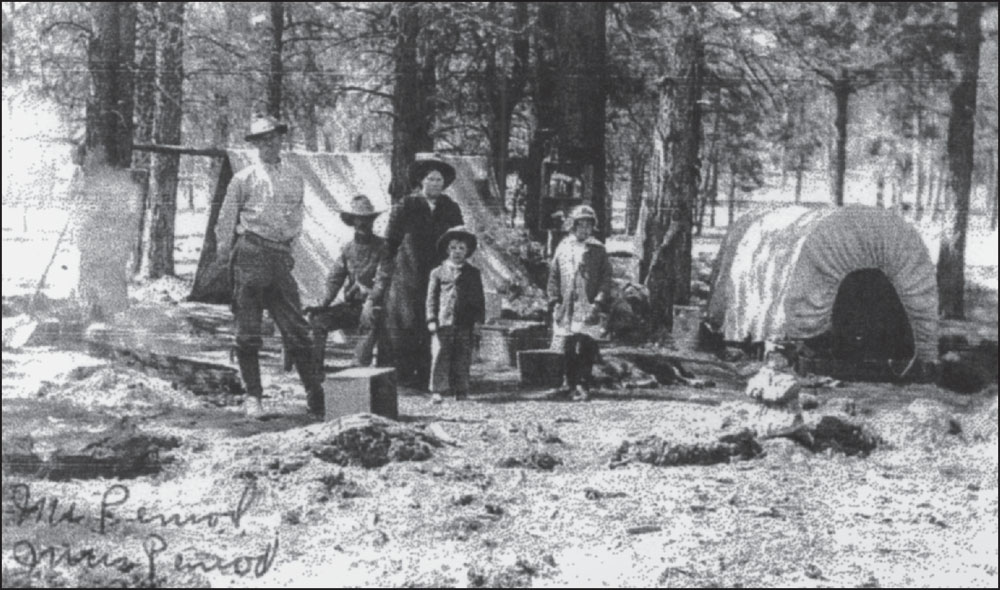

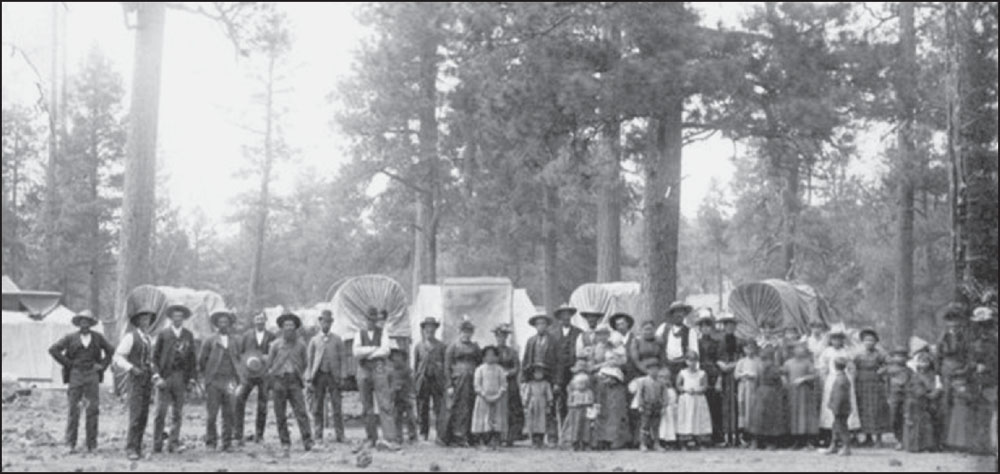

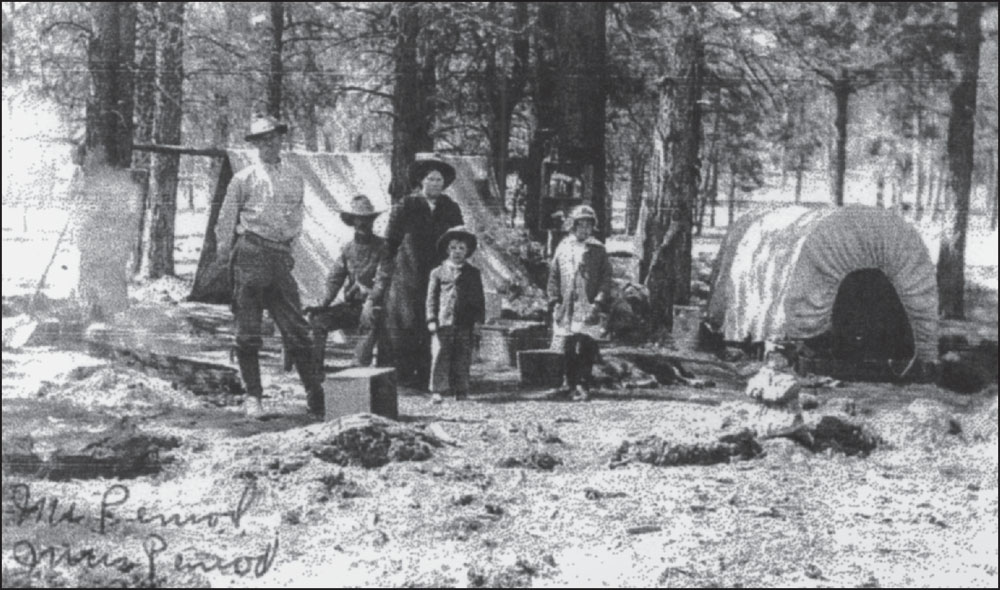

PENROD FAMILY CAMPING TRIP. Pinetop families spent as much time in the woods as they did in town. This family drove to a favorite camping spot in covered wagons and set about getting meat for the winter. (Courtesy Sue Penrod.)

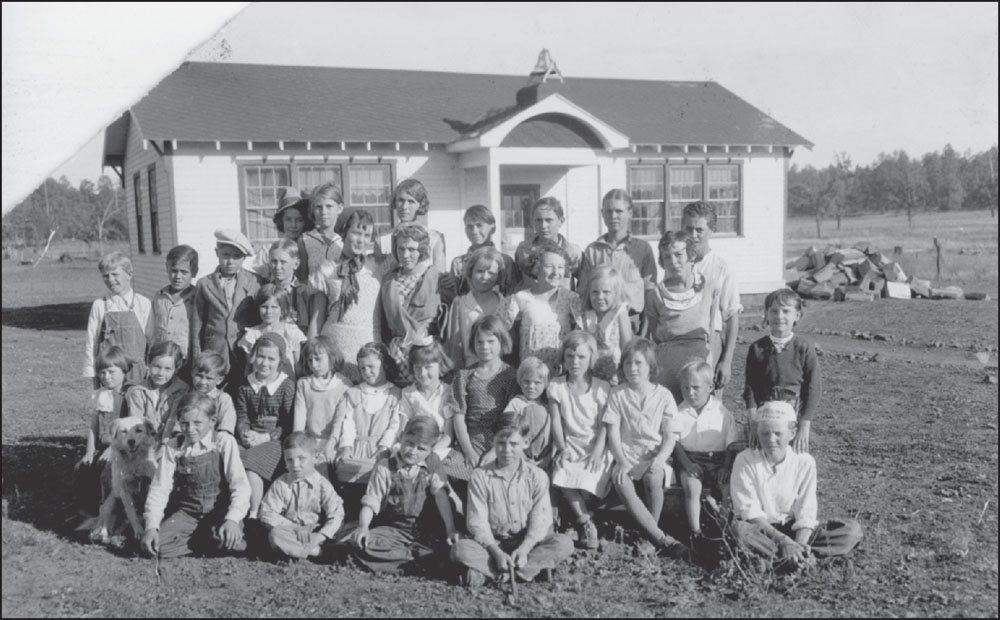

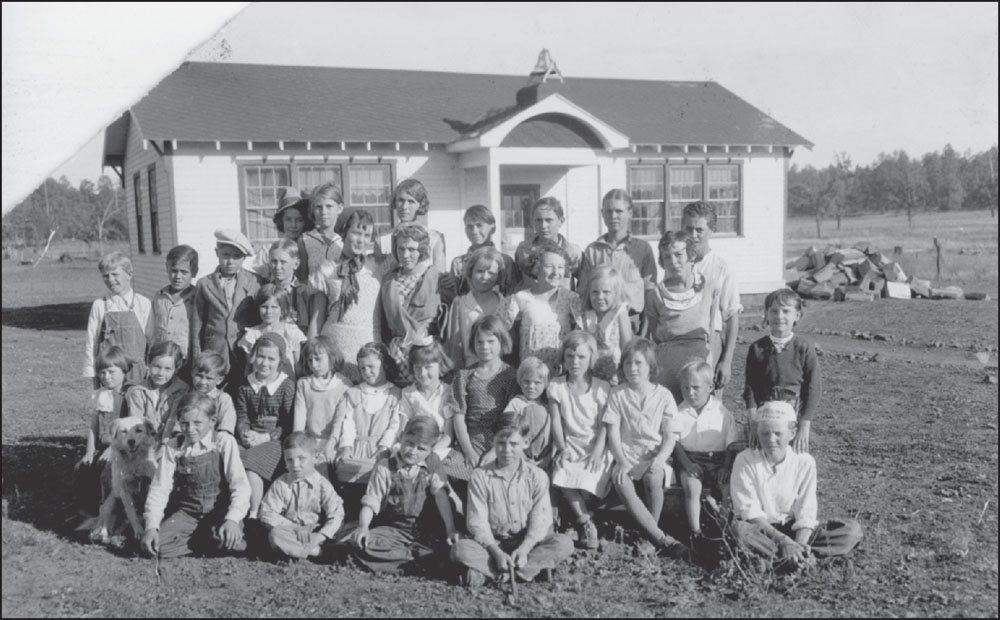

PINETOP SCHOOL. This photograph was probably taken in the 1920s. The one-room school was enlarged as the classes grew. The teacher, Edna Annie Erle Penrod (back row), was from Ohio. At age 26, she took a job teaching school in Pinetop, not knowing where it was. She met Elmer Penrod, who drove the stage from Holbrook to Whiteriver. They were married in 1917 and had one child, Larry Ely. Elmer died in McNary in 1926 of a ruptured appendix. Edna taught in Pinetop, Fort Apache, and Whiteriver for a total of 38 years. Her dog Tippie slept in a box next to her desk. (Courtesy Sue Penrod.)

PINETOP OCCASION. The date of this photograph is not known, but it is probably from the early 1900s. It must have been a special occasion, as most of the men are smoking cigars and the women are dressed up. Arch and Thell were sons of William Lewis Penrod, and Elmer Penrod was Eph’s son. (Courtesy Sue Penrod.)

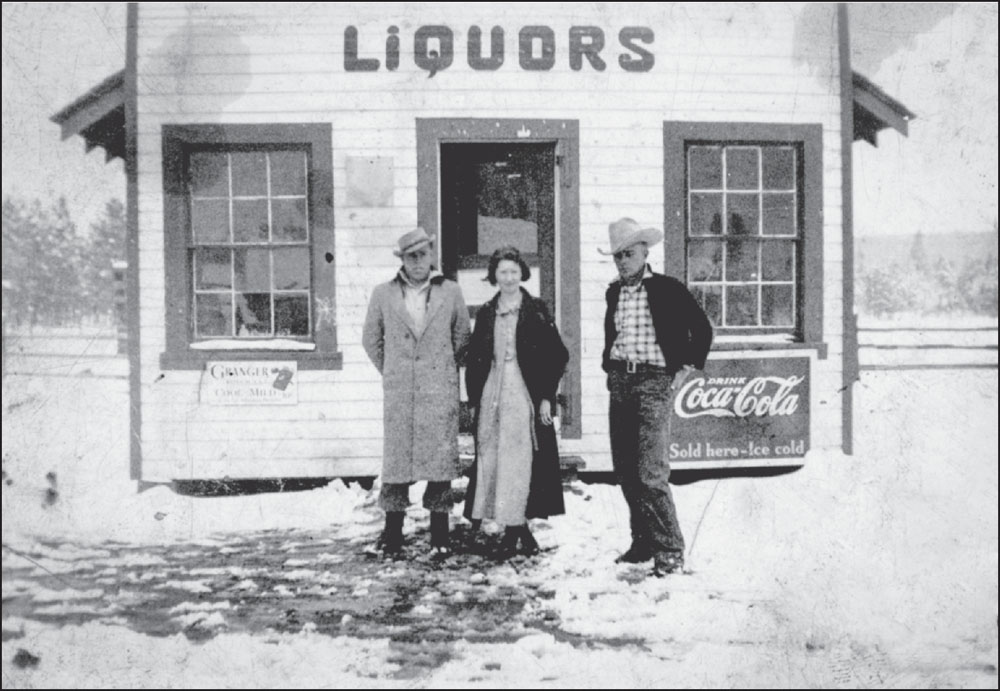

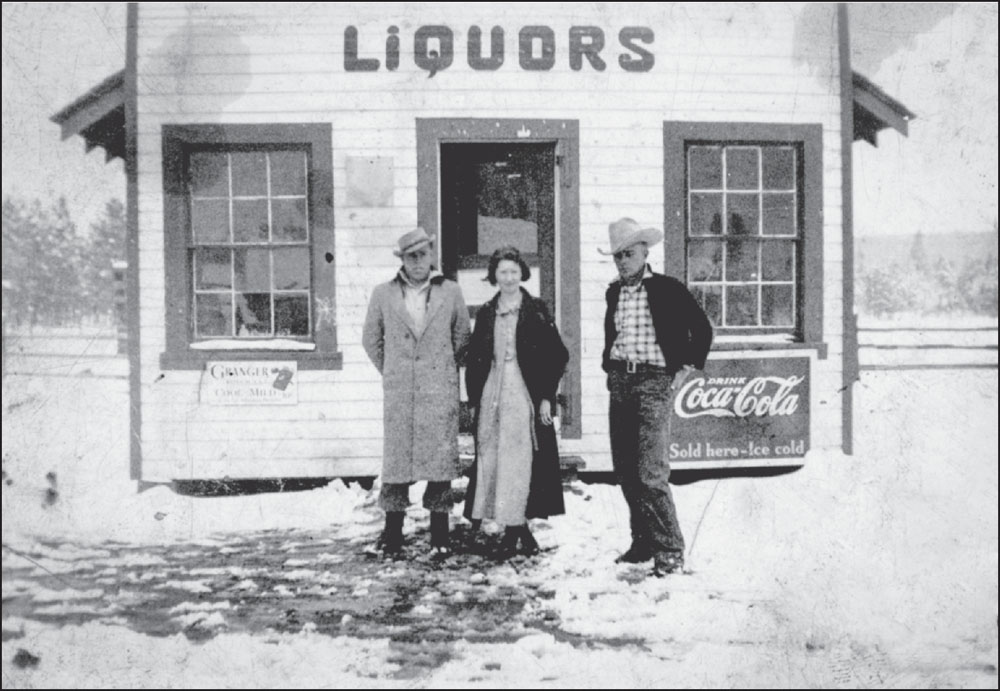

PINETOP LIQUOR STORE ABOUT 1922. “Ice cold Coca-Cola” does not sound very appealing with snow on the ground. (Courtesy Bobbie Stephens Hunt.)

BOBBIE STEPHENS HUNT. Bobbie Hunt sits on a pile of firewood outside her house in Pinetop. She was born in 1934 and grew up during the dark days of the Great Depression and World War II, but always felt blessed to have lived in Arizona’s deserts and forests. She and her husband, Arvil Hunt, moved to Heber in 1963, where they raised their five children. Bobbie is the author of books and articles on the people of the Mogollon Rim country. (Courtesy Bobbie Stephens Hunt.)

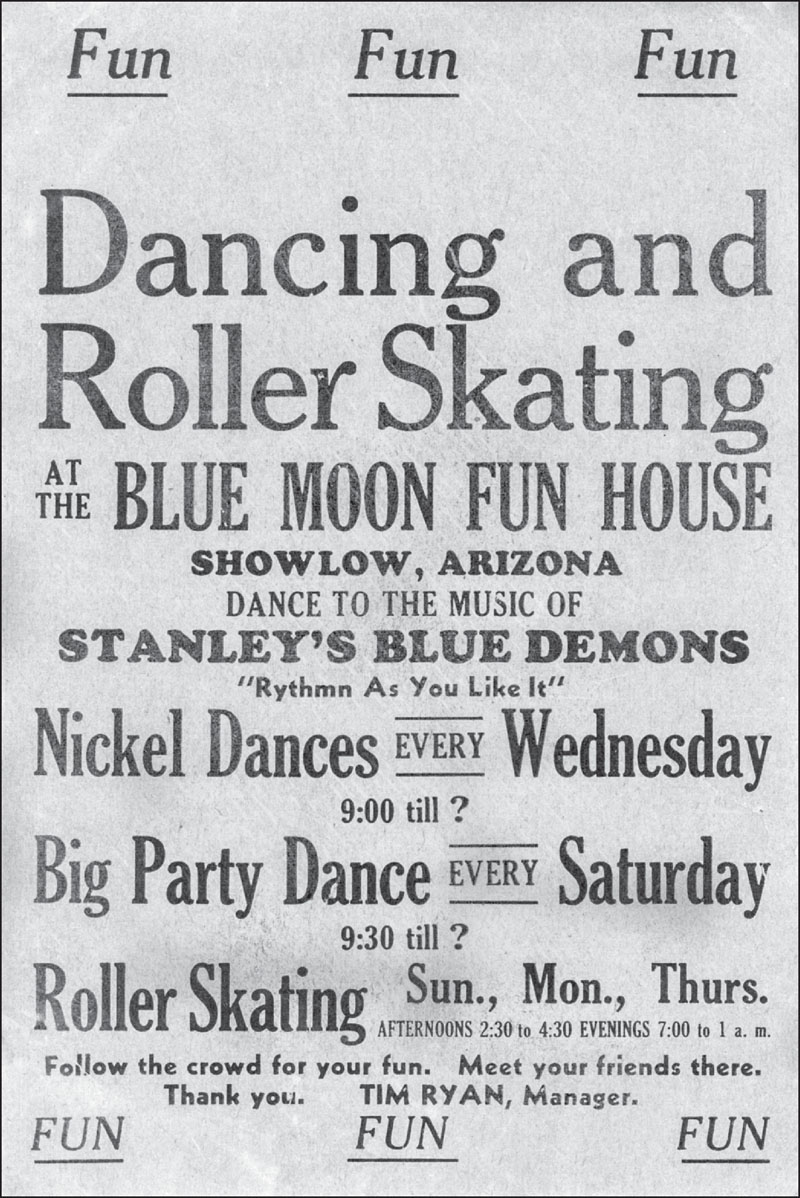

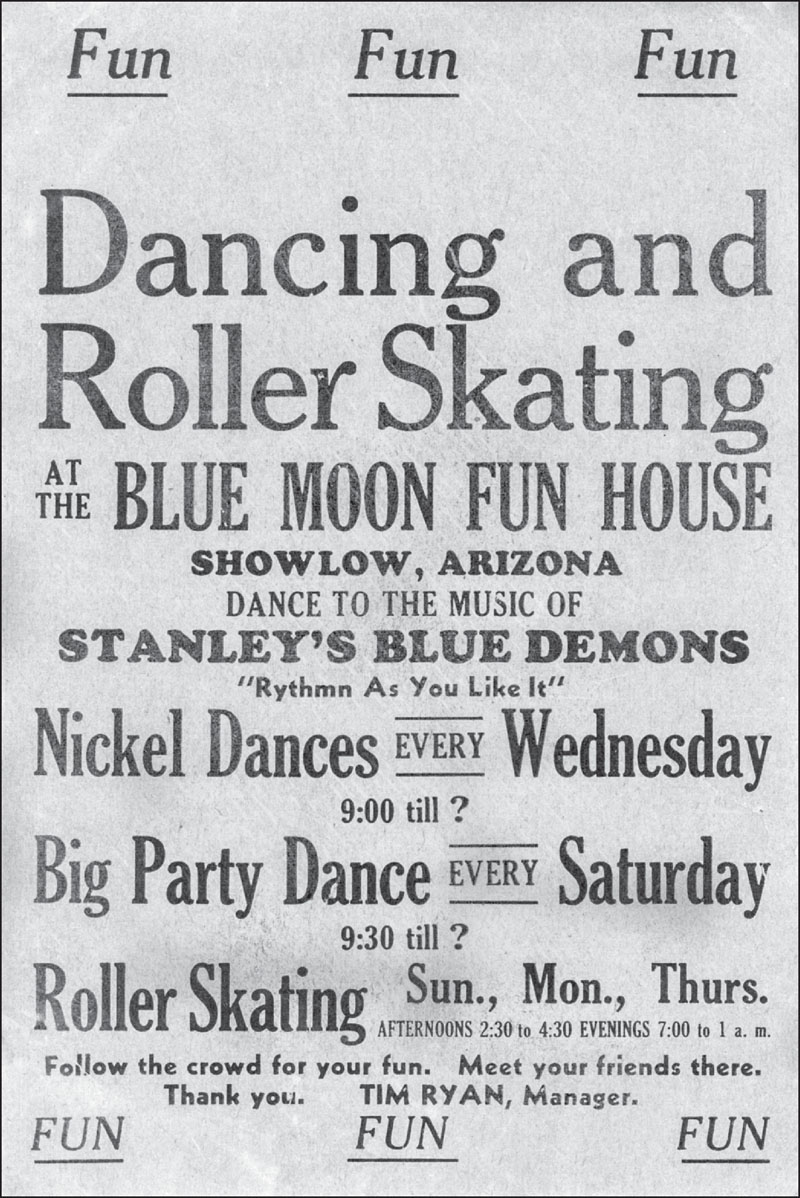

BLUE MOON DANCE HALL. In the 1920s and 1930s, young people from Pinetop and Lakeside drove to the famous Blue Moon Dance Hall in Show Low to have a good time. It was owned by Joe West of Lakeside and Stanley Stephens, whose band, Stanley’s Blue Demons, played there. Bessie Butler, who married Maurice Penrod, wrote, “What fun we had at the dances there. Mrs. Helen Lonsway was always willing to go along and chaperone us girls.” (Courtesy Bobbie Stephens Hunt.)