Five

FORESTERS, LOGGERS,

AND SAWMILLS

The largest contiguous stand of virgin ponderosa pine in the world hugs the Mogollon Rim for 200 miles from the southeast to the northwest across central Arizona. For centuries, the forest remained pristine. Lightning started fires and rain put them out. Apache people set fires in late fall to burn off forest duff and undergrowth. The low-intensity fires did no harm.

The earliest settlers cut only the timber they needed. When Fort Apache was established in 1871, cavalry troopers cut logs for enlisted men’s huts and the commanding officer’s quarters. Construction of a post hospital and other buildings required lumber, so the Army built a sawmill.

Settlers had an opportunity to cut, haul, and sell timber for ties when the Atlantic & Pacific Railroad crossed northern Arizona in 1881–1882.

Corydon E. Cooley built a mule-powered shingle mill on Show Low Creek in the early 1880s and hired William Lewis Penrod to run it. In 1886, Penrod moved his family to Pinetop and built his own shingle mill. Shingles sold for $2.50 per 1,000 and were in high demand.

Small portable sawmills began to spring up. Joseph Fish and Joe Kay set up a sawmill on Billy Creek in Lakeside. A Pinetop sawmill was sold to a group of Lakeside men who set it up at Woodland Dam before 1900. In 1911, Mahonri Lazelle Fish bought their mill and spent the remainder of his life in the lumber business. Despite four of his seven mills burning down, he kept going.

Jonathan Henry Webb and his six sons set up 24 sawmills in Arizona at various times. Webb’s first sawmill was purchased from the Ellsworth family in Show Low in 1918 and set up at the Webb family ranch between Lakeside and Show Low. Their largest operation was at Vernon, east of Lakeside. These entrepreneurs provided jobs for local people and lumber for construction.

Meanwhile, Washington, DC, was taking a closer look at the consequences of the unregulated consumption of natural resources. As early as 1876, Congress created the Office of Special Agent in the Department of Agriculture to assess the condition of Western forests and prevent their wholesale destruction.

The General Provision Act of 1891 authorized the president to set aside forest reserves. In 1905, the forest reserves were transferred from the Interior Department to the Department of Agriculture and administered by an agency henceforth known as the USDA-Forest Service. Approximately 20 million acres of public lands in New Mexico and Arizona came under regional Forest Service administration.

The decision was a blow to pioneer stockmen. Ranchers who had raised cattle or sheep on the public-domain land and Spanish colonial families who had been in the Southwest for 300 years resented Washington bureaucrats telling them how to manage the land and resources they had husbanded.

Pres. Theodore Roosevelt and his friend Gifford Pinchot, the first Forest Service chief, were well aware of the opposition they would face in their mission to manage national forests on a sustainable basis. Pinchot set down the rule: “Where conflicting interests must be reconciled, the question will always be decided from the standpoint of the greatest good of the greatest number in the long run.”

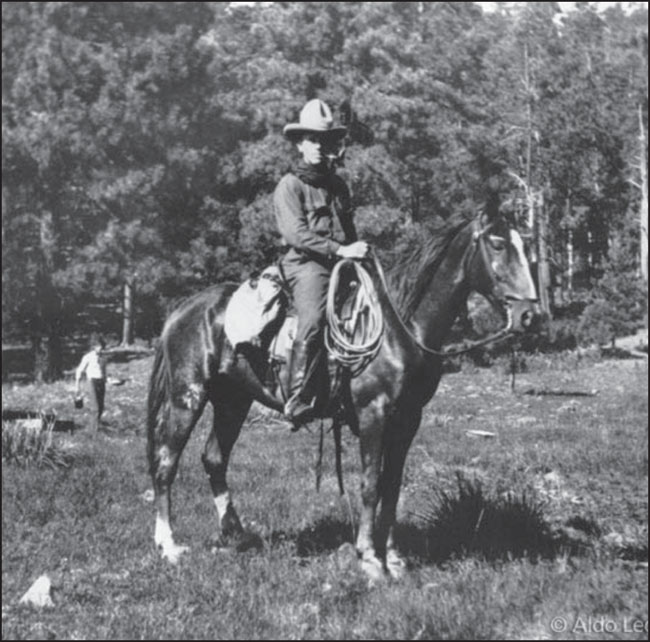

The Apache National Forest was established in 1908. From 1910 to 1912, the timber on both the national forest and the Fort Apache Reservation was inventoried by a group of young Yale University foresters, including Aldo Leopold, author, conservationist, and naturalist.

The nation’s demand for lumber increased in the days leading to World War I. Flagstaff businessmen Tom Pollack and A.B. McGaffey eyed the pine belt and borrowed money to build a sawmill and a railroad that connected it to the Holbrook railhead. They purchased 600 million board feet of timber from the Forest Service and the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and started marking trees for cutting.

Construction began on the Apache Railroad in 1916. Later, railroad spurs were built to remote logging camps. In the beginning, sawmills were set up where the timber was being cut. By 1918, timber was going from the woods to the mill. In 1923, Pollack sold his entire operation to the Cady Lumber Co. of McNary, Louisiana. Cady brought in carloads of experienced workers from its headquarters and built a company town called McNary, after James G. McNary, one of the company partners. The site was leased from the White Mountain Apache Tribe.

The McNary mill was a major economic force in the region, employing up to 750 people. The mill shut down in 1930 when the Depression caused cancellations of lumber orders. The company reorganized as Southwest Forest Mills in 1935. The mill burned down in 1948 but was rebuilt. In 1950, new stockholders changed the name to Southwest Forest Industries. The mill shut down permanently following a 1979 fire. Many McNary residents moved to Pinetop-Lakeside when the mill closed.

Pinetop-Lakeside remains very much a forest community. The Lakeside Ranger District administers 267,000 acres of the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forests. The ranger station has been the center for maps, permits, and information about outdoor recreation for generations.

On the Springer Mountain fire tower, high above the town’s noise and traffic, a Forest Service lookout still watches for smoke.

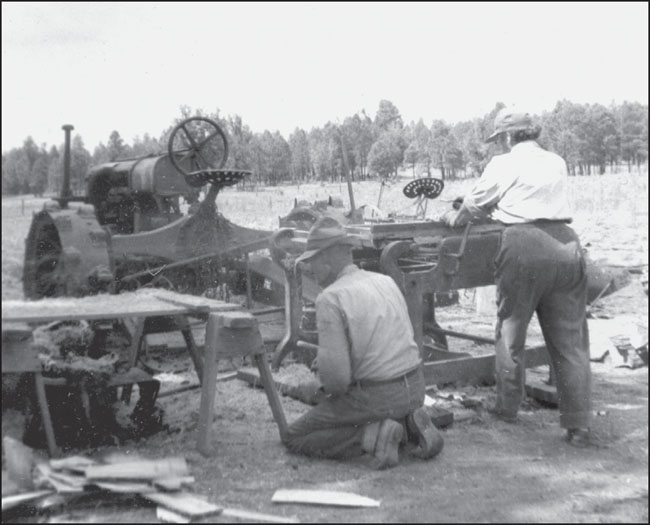

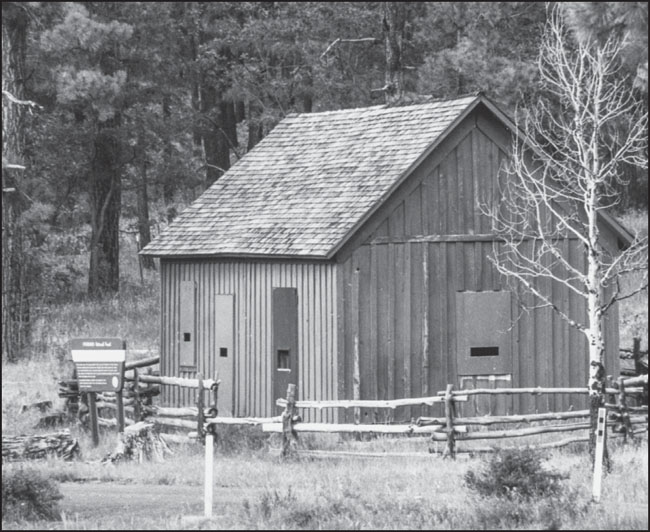

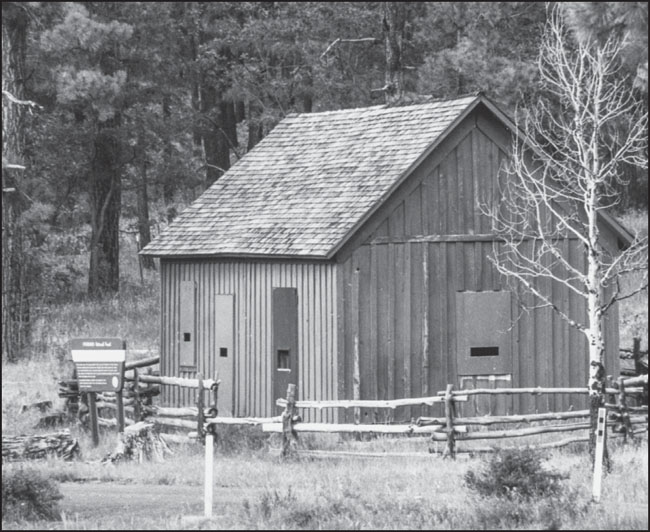

SHINGLE MILL. The first sawmills in the Pinetop-Lakeside area were shingle mills. William Penrod set one up in Pinetop in 1886–1887. They were dangerous machines consisting of a circular saw blade. The operator slid a block of wood over the saw to slice off the shingles. It was an easy way to lose a thumb or finger. (Courtesy Marion Hansen.)

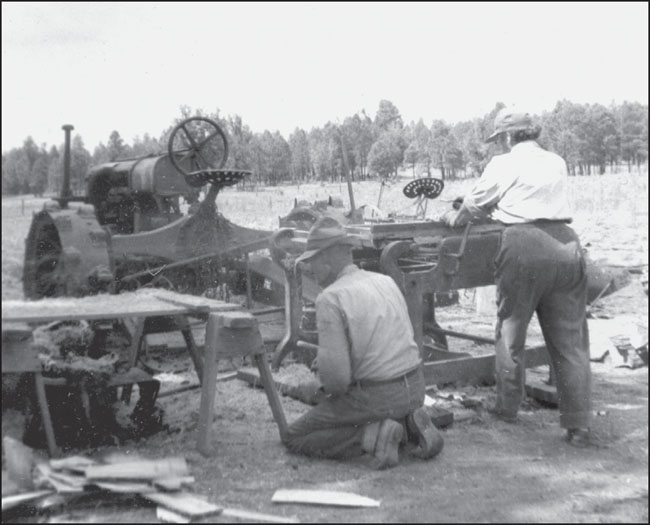

SAWMILL AT WOODLAND DAM. Mahonri Lazelle Fish bought his first sawmill at Woodland Dam in 1911. The old saw frame was part of the sawmill that produced the lumber used to build the LDS temple in St. George, Utah. Nothing was wasted in those days. The mill was dismantled and packed by mule to various settlements in Arizona, with the last parts coming to rest in Lakeside. Sawmills were always at risk for fires and explosions. In 1924, the boiler of this original mill blew up, and in 1928, the roof blew off the building in a cyclone. In June of the same year, Fish lost everything in a fire, including his sawmill, house, and barn. (Courtesy Pam Fish-Tyler.)

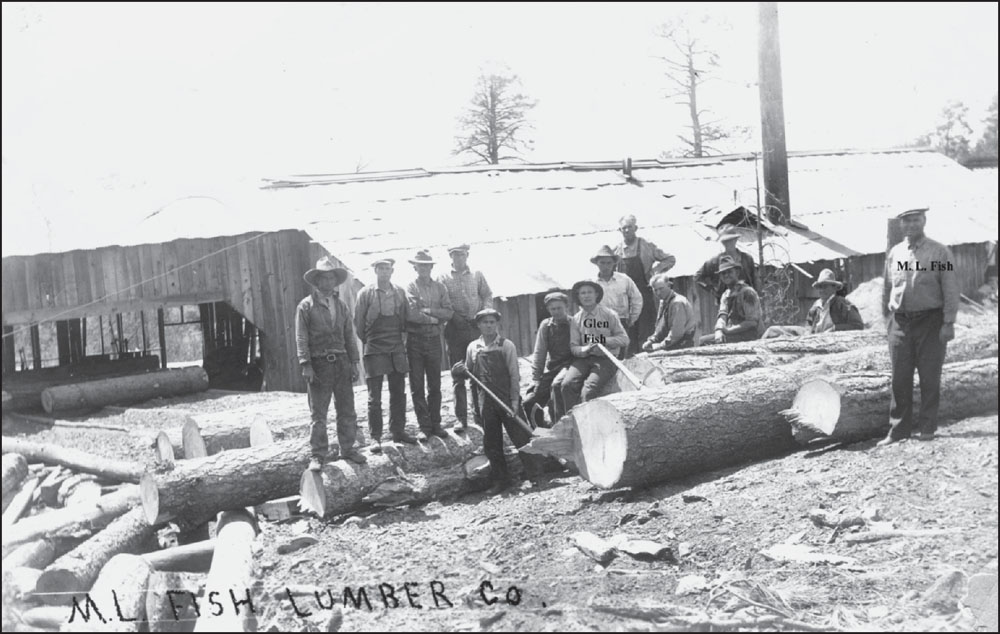

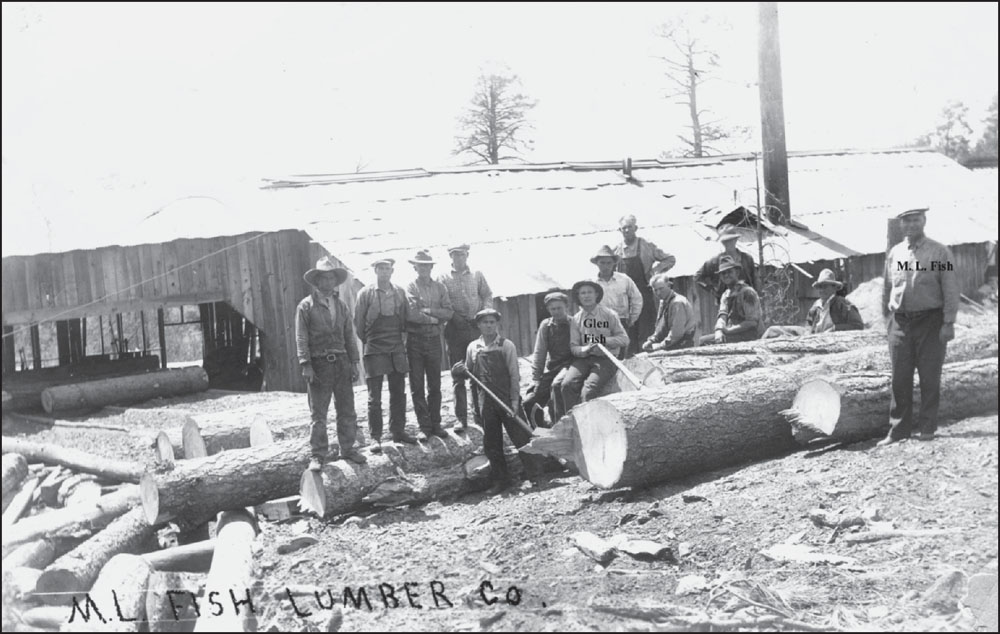

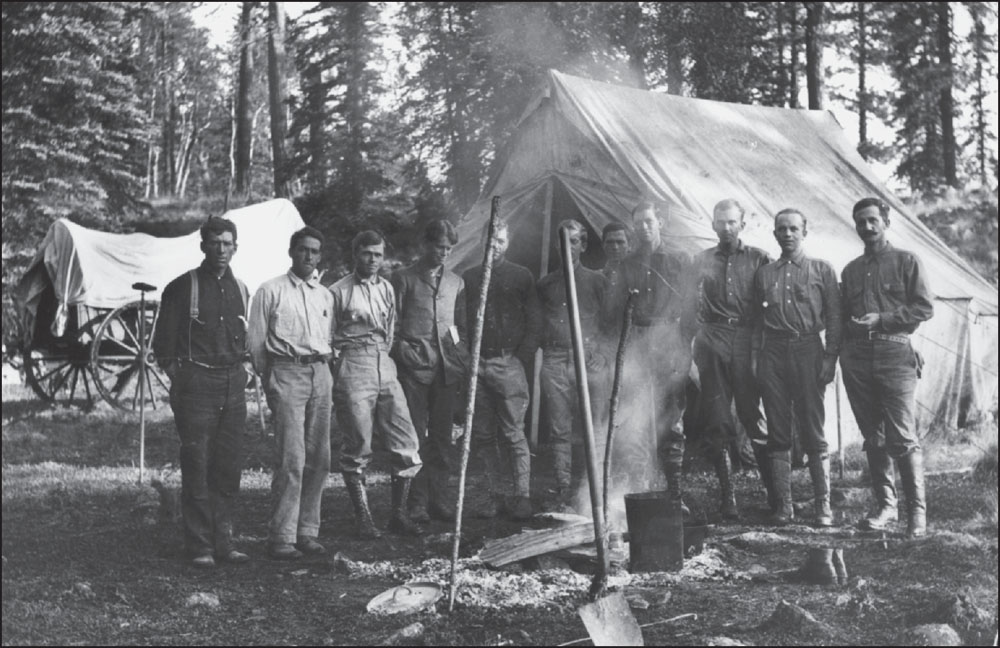

SAWMILL AT WOODLAND ROAD. M.L. Fish and his crew are seen here at a sawmill located off of Woodland Road. Pay slips signed by Fish were used as credit for food at Caldwell’s store. In turn, Caldwell was paid in lumber that he exchanged for groceries and other supplies in the Salt River Valley, according to Leora Schuck. M.L. Fish is the man on the left holding a child. (Courtesy Pam Fish-Tyler.)

WEBB SAWMILL CREW. The largest sawmill set up by J.H. Webb & Sons was the Vernon Mill. Shown in this 1938 photograph are, standing from left to right, Tom Frost, Karl Webb, Waldo Ray, Junius Webb, June Webb, Reece Webb, Fred McNeil, and Jay Webb. Ray Webb is in front. In the early days, sawmills were hauled to the timber stand being cut. Later, timber was hauled to the mills by teams, trains, and then trucks. Sawmilling was the driving force of the White Mountains economy for half a century. (Courtesy Webb family.)

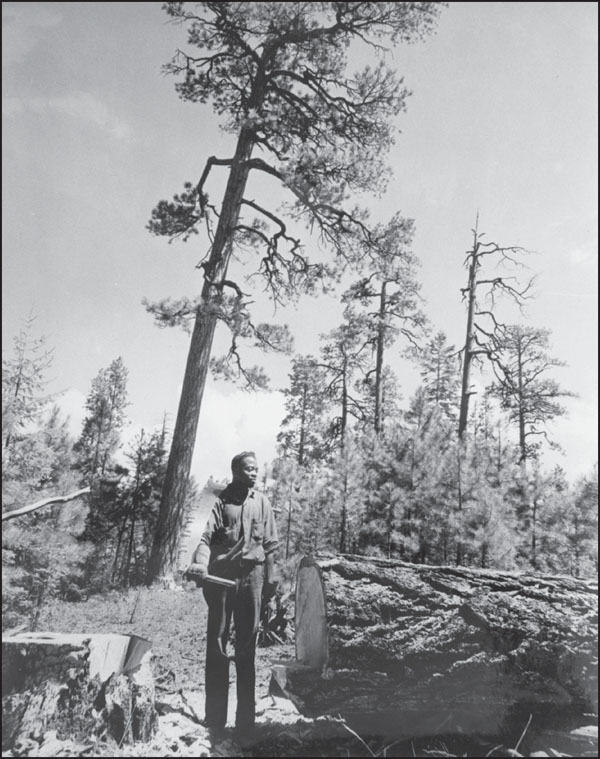

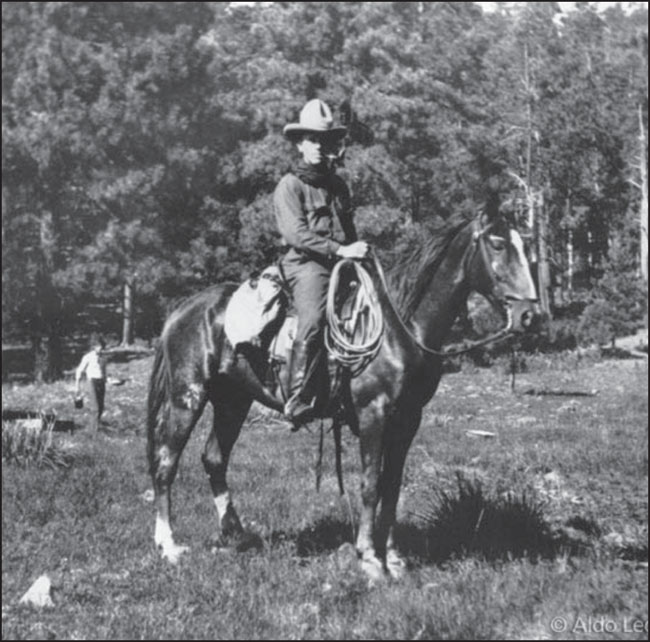

ALDO LEOPOLD IN THE WHITE MOUNTAINS, 1912. Leopold’s philosophical quest led to the belief in a “land ethic” that evolved over several decades into a system of integrated ecosystem management on federal lands. He is best known for his book A Sand County Almanac. (Courtesy USDA-Forest Service.)

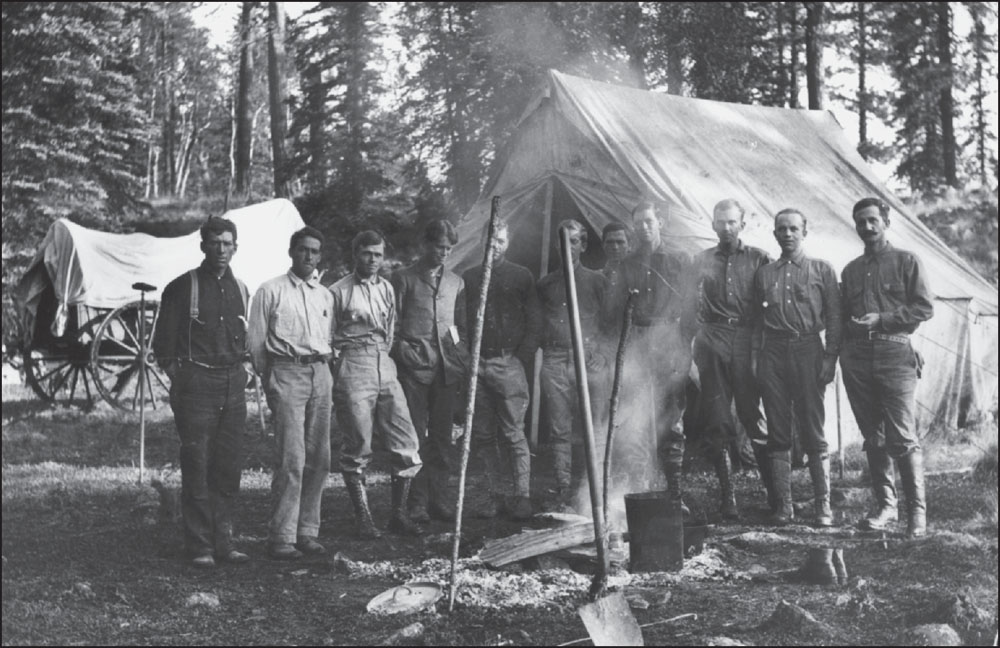

FORESTERS CRUISING TIMBER IN THE WHITE MOUNTAINS. Forestry was a relatively new science in 1910. It began in British Colonial India, where German foresters found ways of preserving valuable teak forests. Germans returned to Europe to teach the “sustained yield” concept. A young American named Gifford Pinchot attended the French National Forestry School and brought his knowledge home. The forests of the White Mountains have always been selectively marked for cutting. (Courtesy USDA-Forest Service.)

LOS BURROS RANGER STATION. The first ranger station in the Lakeside District was constructed in 1909–1910 at Los Burros, east of Pinetop-Lakeside. Approximately 240 acres were set aside for a fireguard, who rode his horse every day to Lake Mountain Lookout, where he climbed a tree to look for fires. If he spotted one, he rode to it and attempted to put it out with hand tools. Los Burros Spring provided water for the fireguard and livestock. (Courtesy Juliette Aylor.)

RAILROAD STATION AT COOLEY. Flagstaff businessmen Tom Pollack and A.B. McGaffey borrowed money from the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe (AT&SF) Railroad to build a sawmill and a railroad in the White Mountains. The Apache Railway ran from Holbrook about 70 miles to a place called Cluff Cienega on the Fort Apache Indian Reservation. The town was first called Cooley, after Corydon E. Cooley, whose ranch was nearby. The name was changed to McNary in 1924 after James G. McNary, a partner in the Cady Lumber Co. of Louisiana, which bought the mill from Pollack and McGaffey. (Courtesy Diana Butler.)

MCNARY MILL. The first small sawmill was put into operation in 1918. The first log sawed was a ponderosa pine about 2.75 feet in diameter, according to Martha McNary Wilson Chilcote’s Memories of McNary, published in 1985. As more workers and supplies were brought in, the mill expanded to the large operation shown in this photograph. The millpond is in the foreground. Southwest Forest Mills, under James G. McNary, employed approximately 750 workers. The town of McNary had a population of 2,000 to 3,000. (Courtesy Diana Butler.)

LOG TRAIN TO MCNARY. The Apache Railway hauled all the logs from the woods to McNary, and all the finished lumber from the mill to Holbrook to be shipped out on the AT&SF. According to Carl Purkins, the railway ran one train three times a week to Holbrook and a daily log train up to the mountains from McNary. Going up, the train often hauled cinders for road building. Southwest Forest Mills built many miles of logging roads all over the forest, which were used later as fire control roads and for access to hunting and fishing sites. (Courtesy USDA-Forest Service.)

APACHE RAILROAD IN WINTER. The Apache Railroad operated with steam engines at first and then switched to diesel. In summer and fall, the railroad had about 125 employees. When the mill had enough logs on deck to last through the winter, and all the cattle and sheep had been shipped from the high country in the fall, the railroad cut back. Trainmaster Carl Purkins wrote, “In spring . . . we would have to clear the railroad of snow into Big Lake landing and on to Maverick to bring in logs to keep Southwest’s big sawmill running.” It took up to 10 days to plow the 67 miles to Maverick. In some of the cuts, the snow was 30 feet deep. (Courtesy Diana Butler.)

UNLOADING SHACKS. Railroad spurs ran to logging camps throughout the White Mountains and Mogollon Rim, including large camps at Maverick and Standard, near the town of Pinedale. The “crates” being unloaded from flatcars are actually shacks that loggers and their families lived in while they were working in the logwoods. The one-room shacks had woodstoves for heat and cooking. McNary residents Pearl and Ozzie Wilson wrote about one especially bad winter: “The logging shacks at the old camp on Horseshoe Cienega were almost hidden by the snow, with only their stove pipes showing where the camp was located.” (Courtesy USDA-Forest Service.)

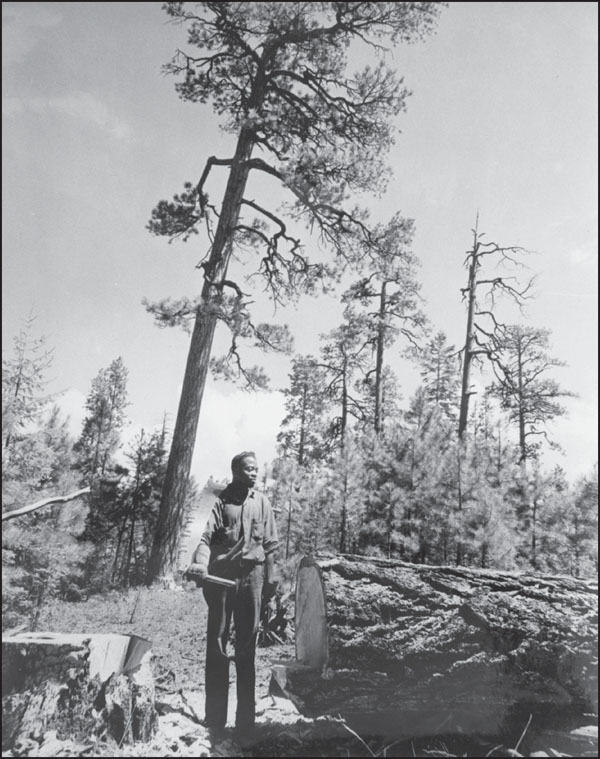

FALLER WITH CROSSCUT SAW. In the early days, trees were felled with two-man crosscut saws, de-limbed with an axe, secured by chokers on the end of cables, and skidded to a landing by horses. A team of horses loaded the logs one by one onto railroad flatcars that hauled them to the McNary mill. Logging continued through most of the winter in spite of deep snow. One of the fallers joked to Martha McNary that Southwest should pay them by the snow they shoveled, not by the board feet they cut. (Courtesy USDA-Forest Service.)

FELLING TIMBER. Some of the early mechanized logging equipment was dangerous. These men are demonstrating the use of a two-man power saw. One man operated a motor mounted on wheels, while the other guided the front of the saw through the log. (Courtesy USDA-Forest Service.)

DE-LIMBING LOGS IN WINTER. Logs had to have the limbs cut off before they could be loaded and stacked, as seen here (Courtesy USDA-Forest Service.)

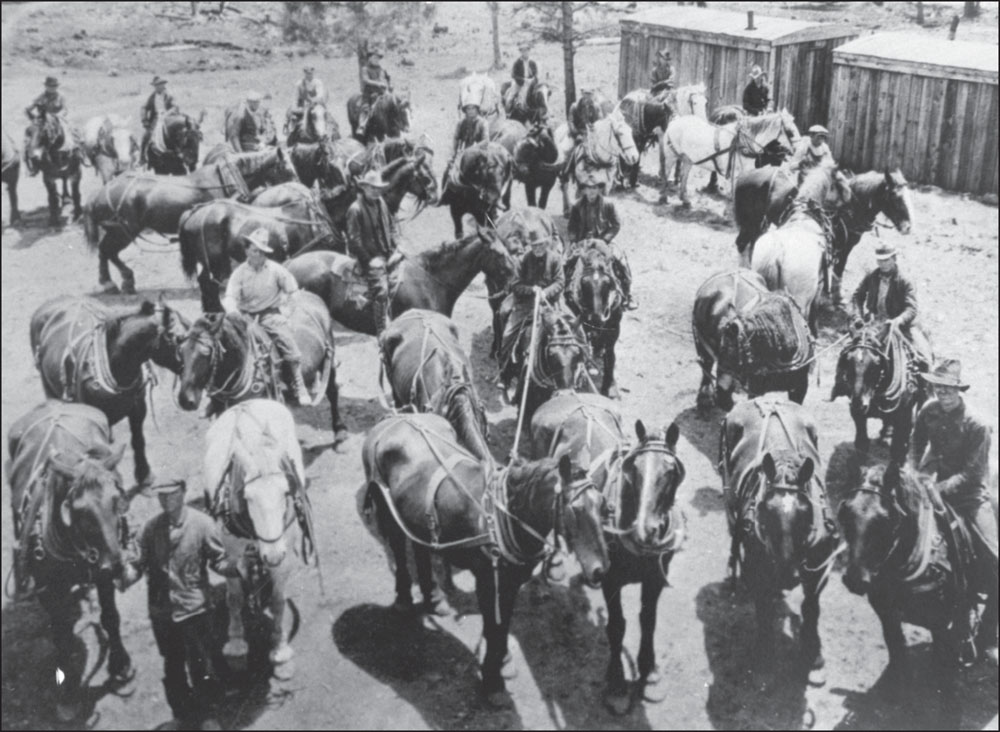

WORK HORSES HAULING A BIG LOAD. Four teams of big workhorses were needed to haul this load of logs from the woods to a railroad spur. When many of the big ranches in northern Arizona sold out in the early 1900s, cowboys and freighters found work with logging companies or with the newly organized Forest Service. (Courtesy Mary Tenney.)

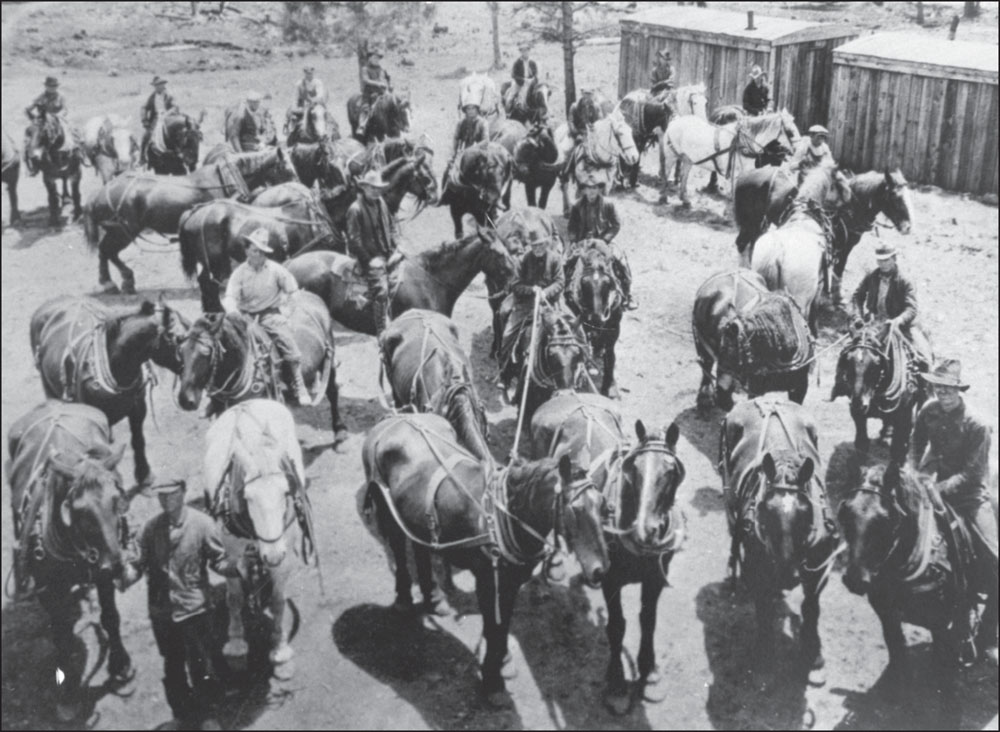

WORK HORSES COMING IN. Horses used for logging were well-trained, disciplined, valuable animals that worked just as hard as their human partners, if not harder. These cowboys are bringing the horses back to camp for a good feed and a night’s rest before another day dawns in the logwoods. (Courtesy USDA-Forest Service.)

TWO-MAN POWER SAW. These early versions of the chainsaw were used for years, both for felling live trees and cutting timber to size for loading or stacking. (Courtesy USDA-Forest Service.)

HORSES LOADING LOGS. Horses were used in logging operations even after trucks began hauling logs. Horses could work in steep country and move around in small spaces. This team seems to be pulling logs onto a truck by means of cables and a ramp. (Courtesy USDA-Forest Service.)

STEAM-POWERED CABLE LOADER. The loader operator had to know how to run the boiler that powered his engine, as well as how to operate the equipment. These men are loading logs from the landing onto flatbed railroad cars. (Courtesy USDA-Forest Service.)

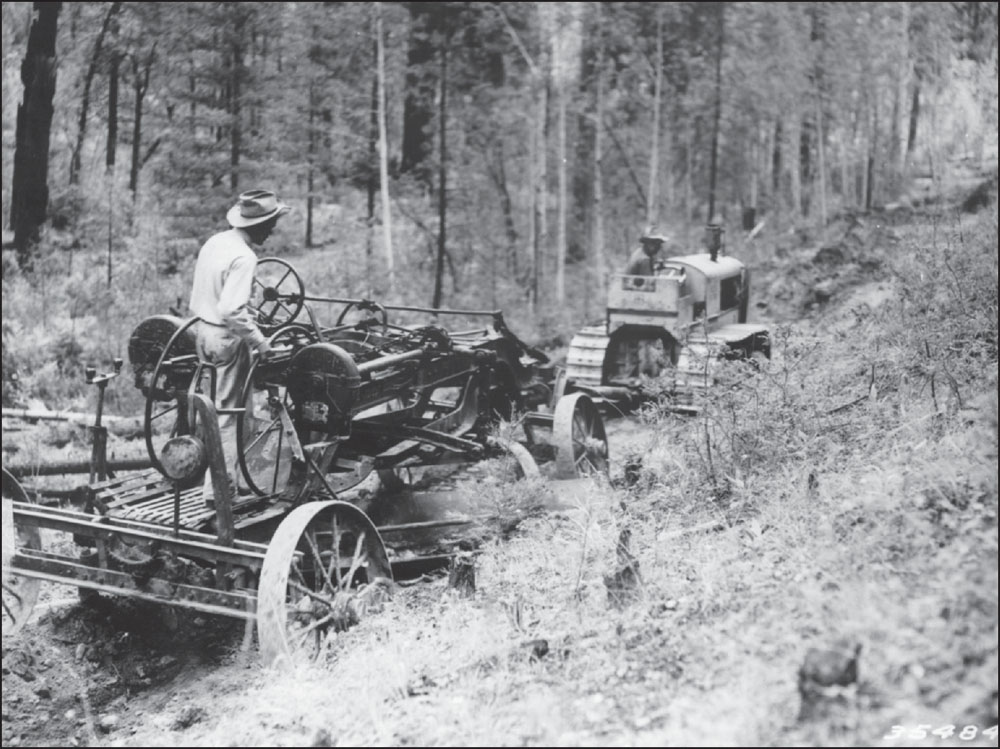

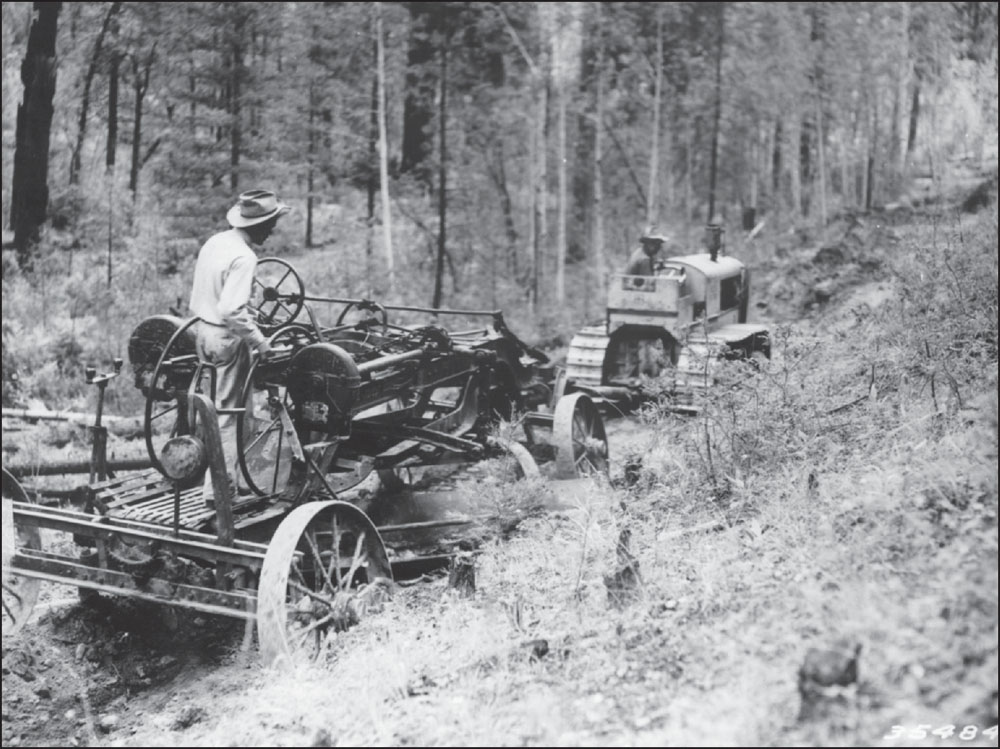

ROAD GRADER. Early road graders did not have their own engines. They had to be pulled by “cats,” Caterpillar tractors. One man drove the tractor, while the other steered the grader. (Courtesy USDA-Forest Service.)

TRUCKING LOGS TO THE MILL. Logging trucks had to handle some steep grades. Southwest used Kenworth and Sterling trucks that could haul as many logs as a railroad flatcar. (Courtesy USDA-Forest Service.)

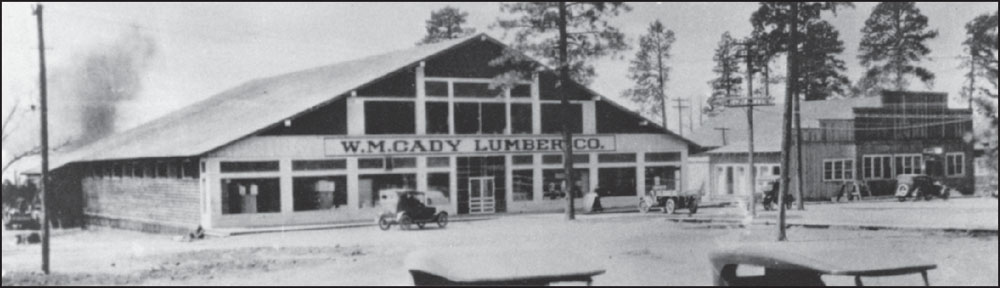

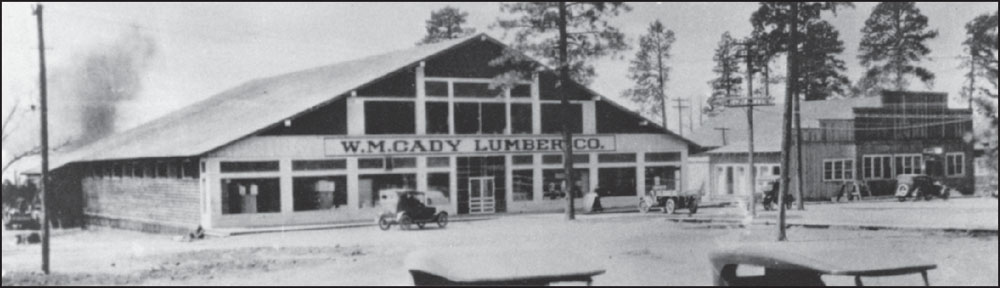

CADY COMPANY STORE. Cady changed the name of the Apache Lumber Co. to Cady Lumber Co., and the town of Cooley to McNary. This is the first company store, which burned down. Employees could charge what they needed through the winter, and it would be taken out of their paychecks when work started up. (Courtesy Diana Butler.)

MAIN STREET, MCNARY. McNary was a “metropolis” of more than 2,000 when Pinetop and Lakeside were still mountain hamlets. Planned and built by a Louisiana company, living quarters were as segregated as they were in the South. Spanish and African American “quarters” were down by the millpond. Each had its own elementary school and café. White people lived in company housing on the hill above the mill. Navajo brush cutters and Apache workers had their own villages just over the line in Navajo County. Everyone worked together, went to the same high school, and played on the same teams, but they could not sit together at the movies. Housing segregation continued until the Civil Rights Act of 1964. (Courtesy Diana Butler.)

APACHE HOTEL. The Apache Hotel was built about 1919 and served as a boardinghouse for mill workers as well as visitors. Grayce Quick Peterson managed the hotel and dining room for about 20 years starting in 1945. The hotel was only one of McNary’s amenities. The company town had a commissary, offices, a guesthouse for VIPs, a post office, a bank, a café, a garage, a movie theater, a bowling alley, a hospital, a clinic, a fire department, and churches. (Courtesy Diana Butler.)

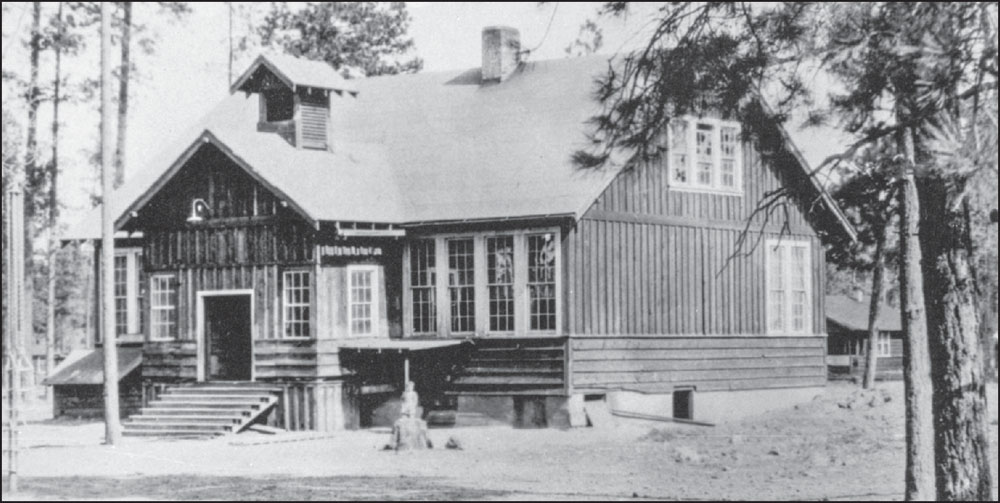

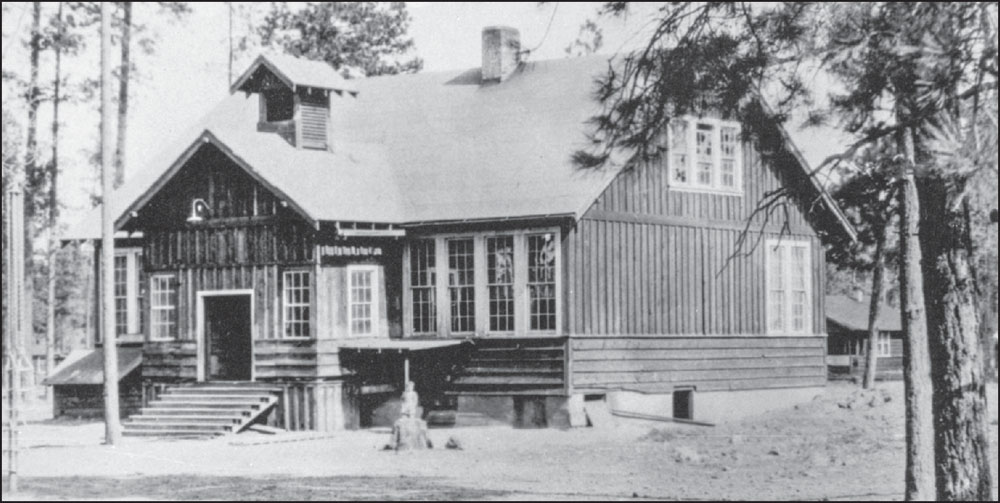

MCNARY SCHOOLHOUSE. The first schoolhouse consisted of four classrooms, with two grades in each room. Later, a high school was built. If children in Pinetop-Lakeside wanted to finish their last two years of high school, they had to choose between McNary and the Snowflake Academy, as there was no high school in either of their communities. The first high school graduating class in Lakeside was in 1932. Rev. Arthur Guenther said, ”What really broke down the barrier of segregation was the McNary Green Devils, especially the football and basketball teams.” With only 150 high school students, the Green Devils won 85 percent of their games in the 1960s and were undefeated from 1964 to 1966. (Courtesy Diana Butler.)

CHAPEL IN THE PINES. A community church called Chapel in the Pines was built in McNary in the late 1930s and used by several denominations. Protestants drove from Pinetop and Lakeside to attend services here until churches were built in their communities. St. Anthony’s Catholic Church was the first church built in McNary. Father Augustine, a Franciscan, was the priest in the 1920s and 1930s. There were two Baptist churches in the “Negro Quarters.” Lutheran pastor Arthur Guenther held services and Sunday school in Whiteriver, McNary, Maverick, Fort Apache, Springerville, and Show Low. Latter-day Saints missionaries visited homes throughout the area. (Courtesy Diana Butler.)

MCNARY HOSPITAL. Logging is one of the most dangerous jobs on earth. A company hospital was a necessity for mill workers, loggers, and their families. The McNary clinic and hospital were godsends for the entire region. People came from 100 miles or more to receive medical care. The hospital also helped break down segregation. One of Dr. Arnold Dysterheft’s first acts was to have the wall that segregated patients in the waiting room torn down. (Courtesy Georgia Dysterheft.)

MCNARY HOSPITAL STAFF. The McNary Hospital staff is seen here around 1941. From left to right are Dr. Arnold H. Dysterheft, nurse Hilda Mayfield, dentist Dr. Ed Higgins, nurse Zena Higgins, and Dr. Kenneth Herbst. (Courtesy Georgia Dysterheft.)

“DR. D” TREATING A PATIENT. “Dr. D,” as Dr. Arnold Dysterheft was known to the community, treats Wyatt “Dukum” Young in the x-ray department of the McNary clinic. The nurse is Mary Stiles. (Courtesy Georgia Dysterheft.)

SHIRLEY JONES, A FRIEND TO ALL. Shirley Ann Stratton Jones came from a Show Low pioneer ranching family. She worked as a nurse and nurse practitioner for more than 50 years, mostly in the White Mountains. For the last 30 years of her career, she worked on the White Mountain Apache reservation. A Pinetop resident, she rarely went into a store without stopping to talk to someone she had cared for. (Courtesy Georgia Dysterheft.)

FELLERBUNCHER AT WORK. Logging has come a long way since the early days of two-man crosscut saws, but it is still an important part of the White Mountains economy. This Fellerbuncher can roll through the woods, shear off small-diameter logs at the base, bunch them up, and carry them to a machine that grinds the trees into chips. This monster machine belongs to Future Forest LLC, a business committed to forest restoration. (Courtesy Future Forest.)

FORWARDER. Another heavy equipment giant used by Future Forest is called a Forwarder, a truck that loads itself—a far cry from the days when logs were loaded one at a time by a team of horses. Future Forest works on thinning projects that remove the smaller-diameter trees that act as fuel for wildfires. Thinning provides space for larger ponderosa pines to thrive and grow approximately 300 percent faster. (Courtesy Future Forest.)

LOG TRUCK. A Kenworth truck is seen coming down off Green’s Peak with a load of small-diameter timber. The trees still have the limbs in place so there will be no logging debris on the ground to catch fire. The purpose of thinning is to sustain natural, resilient forests and protect communities like Pinetop-Lakeside from the threat of wildfires. (Courtesy Future Forest.)

CHIP TRUCK. Small trees are fed into a chipper that feeds the chips into a truck bed. The chip truck transports these chips to the Forest Energy Corporation wood pellet plant in Show Low. Rob Davis is the owner and president of Forest Energy Corporation, which manufactures wood pellets for fuel, animal bedding, absorbents, and a five-pound compressed wood log for use in fireplaces and woodstoves. The majority of wood materials used are obtained directly from forest restoration projects. (Courtesy Future Forest.)