Six

HARD TIMES

TO GOOD TIMES

As the 20th century dawned, Pinetop and Lakeside were still remote, sparsely populated towns in the midst of a vast pine forest, halfway between Holbrook and Fort Apache. Families made a spare living raising livestock, farming, freighting, sawmilling, or working away from home. Life was good, but making a living was hard.

In 1910, the US Census showed the Lakeside population as 114, and Pinetop as 95. Ranchers in southern Navajo County numbered 52, most of whom were Hispanic sheep men.

The seeds of a recreation-based economy were planted early on. Arizona lawmen took their rifles and packhorses to the White Mountains to hunt deer and turkey when they were tired of hunting outlaws. Outlaws hid out in the mountains when they were tired of being hunted by lawmen. For the most part, they avoided each other, but if an arrest was made, the deputy handcuffed his man to a pine tree and left him there until he was ready to escort him to jail.

In summer, LDS families drove to Lakeside in wagons from Little Colorado River colonies to visit relatives and camp in the cool pines around Rainbow Lake. Townspeople in Holbrook and Winslow called the Mogollon Rim and the White Mountains “Up Country.” They considered mountain people a bit rough around the edges, but loved to dance to mountain bands. Pinetop and Lakeside bands were famous. Dances lasted all night, and sometimes all weekend. Cowboys rode in off the range to whoop and stomp at Penrod’s dance hall or the Cooley Ranch.

Lakeside pioneer Alof Pratt Larson hauled the first two barrels of rainbow trout fingerlings in a wagon from the railroad in Holbrook to Lakeside in 1909. A procession followed him to the headwaters of the lake, where the tiny fish were turned loose. A few years later, Niels Hansen brought home a couple of small trout he had caught in the lake. His wife, known as “Aunt Belle,” fried them and divided them up so everyone at their table could have a taste.

In spite of their relative isolation, Pinetop-Lakeside residents did their part in World War I. Women knit sweaters and socks for the troops. The mountain did not escape the Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918–1919. The flu was rampant on the White Mountain Apache reservation. Rev. Edgar Guenther nursed Chief Alchesay and others back to health with home remedies. His wife, Minnie, cooked gallons of nourishing soup and delivered it by wagon to flu victims in isolated camps.

Schoolteacher A.W. Atherton published a publicity pamphlet in 1918 extolling Lakeside as “a beautiful, wholesome place to live.”

Prosperity took hold in the mid-1920s due to the nation’s increasing demand for lumber. The Apache Railway and McNary Mill ran at capacity. The lumber business brought in more than 2,000 newcomers and provided jobs for hard-pressed local people. Workers could buy almost everything they needed at the company store—almost.

The 18th Amendment to the US Constitution, passed in 1920, prohibited the production, sale, importation, or transportation of alcoholic beverages. Arizona’s territorial legislature had already voted to shut down saloons and breweries in 1915.

Few people in Arizona took Prohibition to heart. There were no speakeasies in the mountains, but hidden in the pinewoods were countless stills for making illegal whiskey. Moonshiners and bootleggers did a land office business in Pinetop until Prohibition was repealed in 1933.

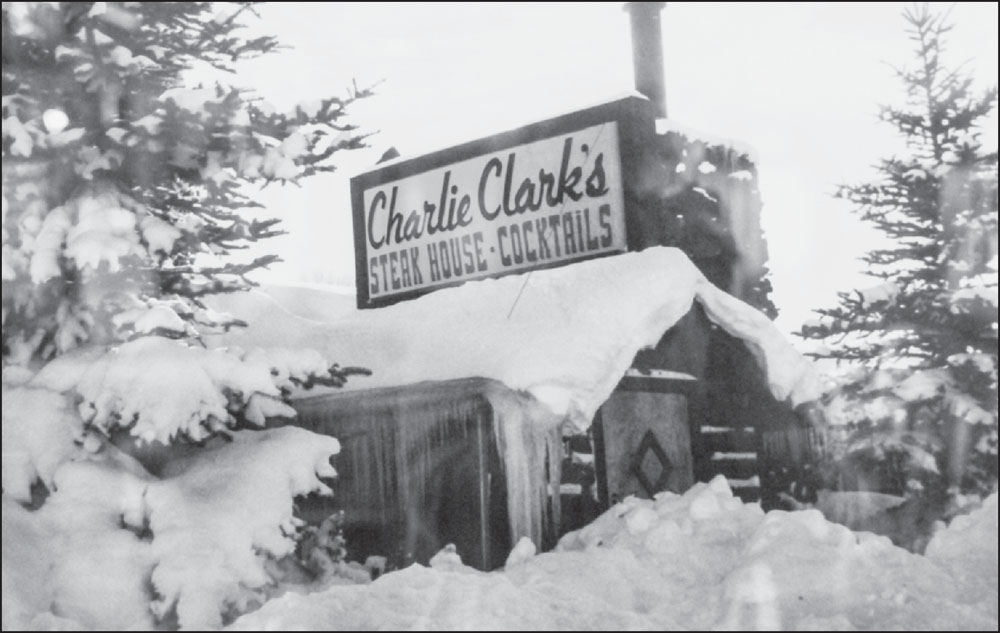

One such entrepreneur was World War I veteran Jake Renfro. He and his wife, Blanche, moved to Pinetop in the 1920s because they both loved to hunt and fish. In addition to making a lot of friends, Jake made “white lightning.” When Prohibition was repealed, he pulled two log cabins together and opened a legitimate business he called Jake Renfro’s Famous Log Cabin Café. He sold the café to rancher Charlie Clark in 1938. It has been in business ever since under different owners. In addition to food and drink, Charlie’s served as a clearinghouse for business deals, politics, news, and fishing information.

Lakeside residents had their own version of good times. The June Moon Water Festival was the biggest event in northern Arizona in 1928. All festivities revolved around the lake. It was Lakeside’s first attempt to promote tourism statewide. Activities included the Grand Pioneer Parade, a reenactment of a stagecoach holdup, an all-night Crown Dance by White Mountain Apaches, rodeos, matched horse races, barbecue, watersports, footraces, concerts, and moonlight dances. The Lakeside Pavilion was the largest dance pavilion in the state. The June Moon Festival was highly publicized. People from all over Arizona began coming to Pinetop and Lakeside to fish, hunt, camp, and cool off.

The major obstacle to tourism remained the inaccessibility of the area. Tourists from the Salt River Valley had to drive north to Flagstaff, 100 miles east to Holbrook, and then south 60 miles to Pinetop. People who lived on the mountain usually took a treacherous, narrow dirt road through Whiteriver to get to Globe, Safford, or Phoenix. In 1933, the US Congress funded the Public Works Administration to build a bridge in Salt River Canyon on the White Mountain Apache reservation. The project employed many local workers, including Apaches. In June 1934, access to the White Mountains was shortened with a single-span, steel-arch bridge across the Salt River.

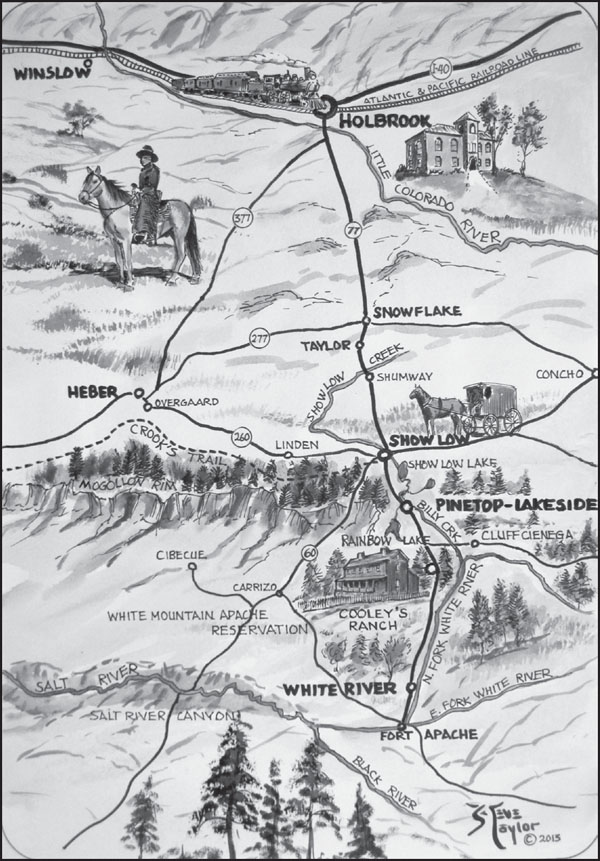

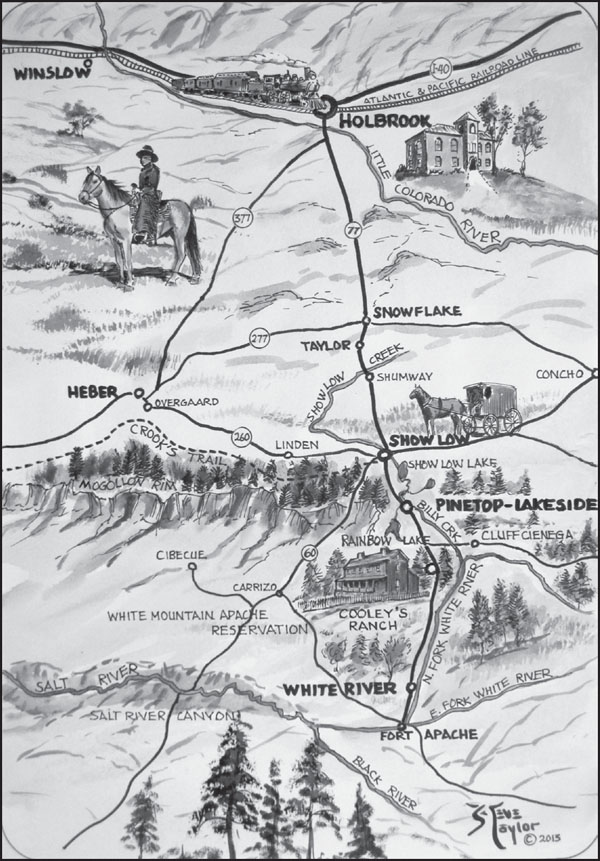

THE WAY IT WAS. In 1900, Pinetop and Lakeside were not much more than wide places on the Holbrook–Fort Apache road. Johnny Phipps and Billy Scorse sold groceries and liquor in their respective stores. William Penrod ran a shingle mill in Pinetop. The first LDS settlers had built Woodland Dam and were working on a bigger dam. Cattle and sheep ranches were sparsely scattered throughout southern Navajo County. (Map by Steve Taylor.)

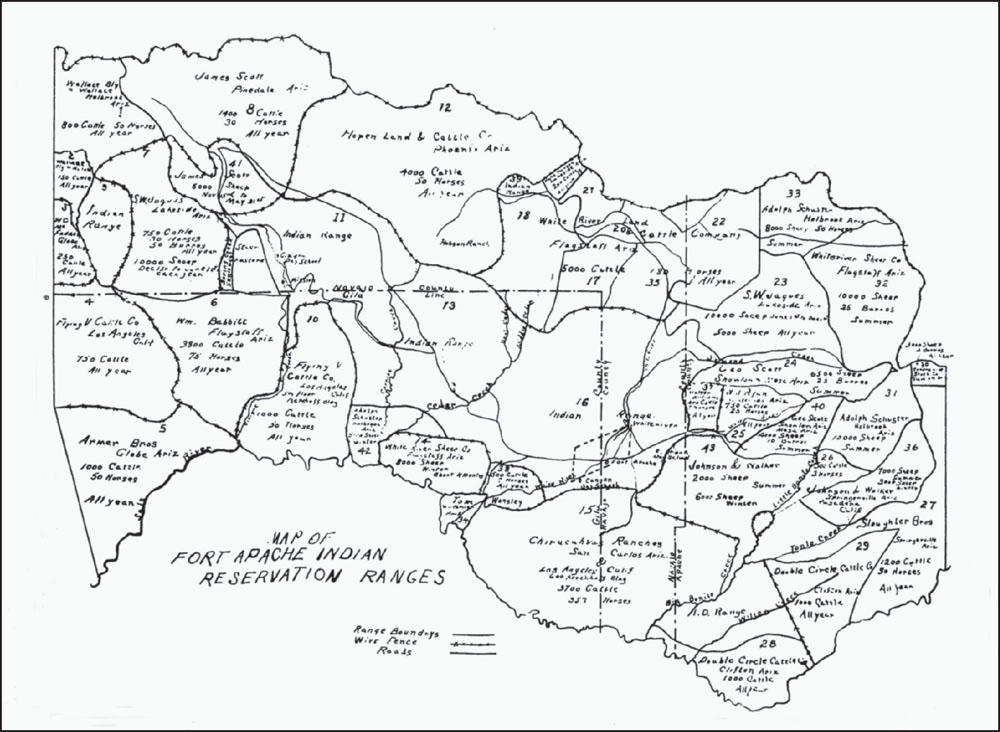

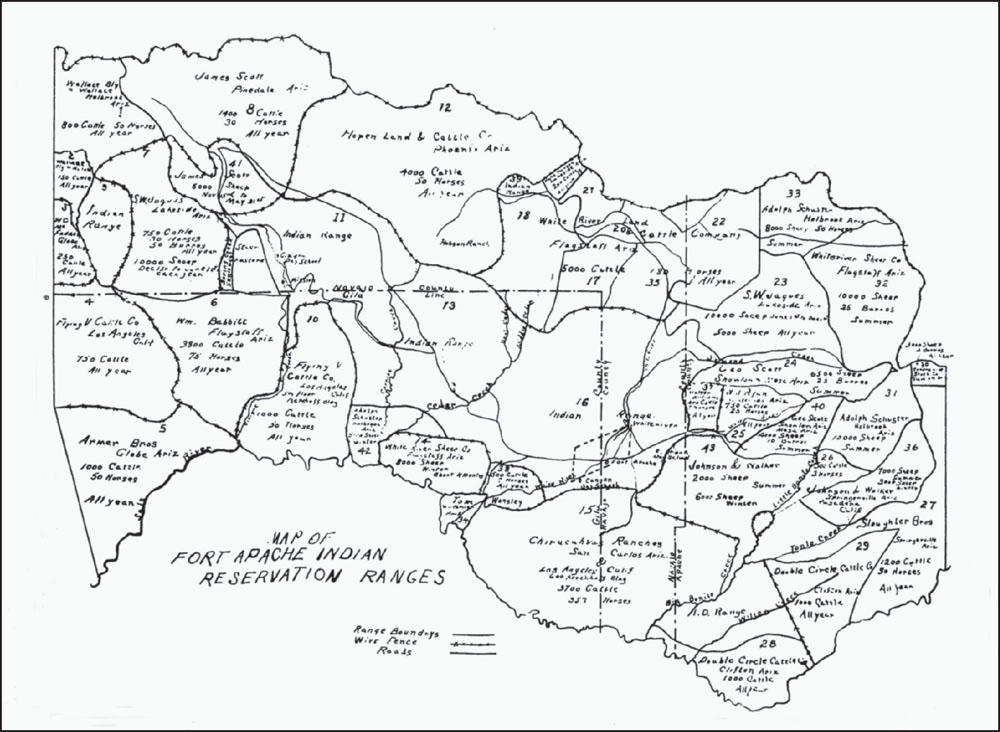

FORT APACHE RANGE ALLOTMENTS. This map from around 1920 shows that most of the rangeland on the White Mountain Apache reservation was being used by non-Indian stockmen from as far away as California. For a grazing fee, large outfits could run thousands of sheep, cattle, horses, and burros on Apache ranges. Leasing by non-Indian stockmen ended in 1930. Finally, in 1953, a Tribal Council ordinance was passed stating that only livestock belonging to a tribal livestock association could graze on the reservation. (Courtesy Dan Carroll.)

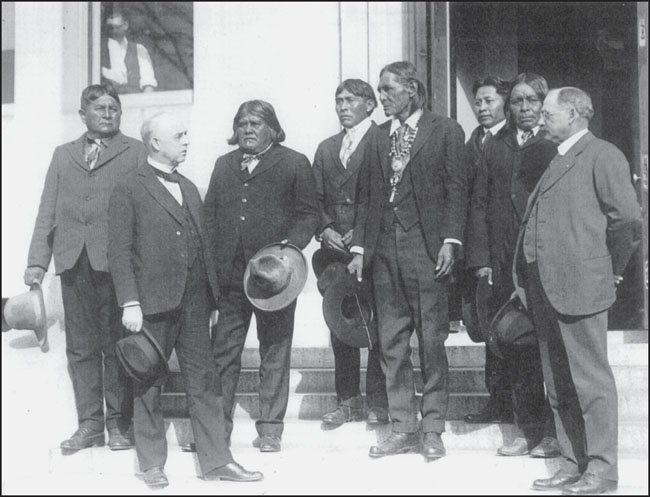

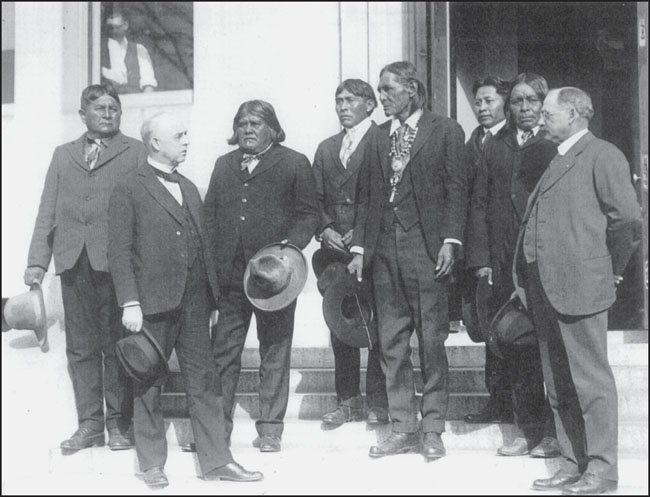

APACHE CATTLEMEN IN WASHINGTON, C. 1920. Chief William Alchesay, Wallace Altaha, and other Apache cattlemen traveled to Washington, DC, to discuss grazing rights, herd improvement, and range management issues on the White Mountain Apache reservation with US officials. (Courtesy Guenther Collection, Pinetop-Lakeside Historical Society.)

BILLY SCORSE IN 1912. Billy Scorse, an Englishman for whom Billy Creek is named, came to Lakeside in the 1880s. He raised sheep and sold groceries and liquor. Sometime after selling his property to John L. Fish in 1907, Scorse moved to Holbrook, where his brother H.H. Scorse had a mercantile business. Billy is pictured second from the right, with his nephew William and Will’s boys Harry and Richard. Billy died on March 24, 1933, in Wilmington, California. (Courtesy Maryann Scorse Coulter.)

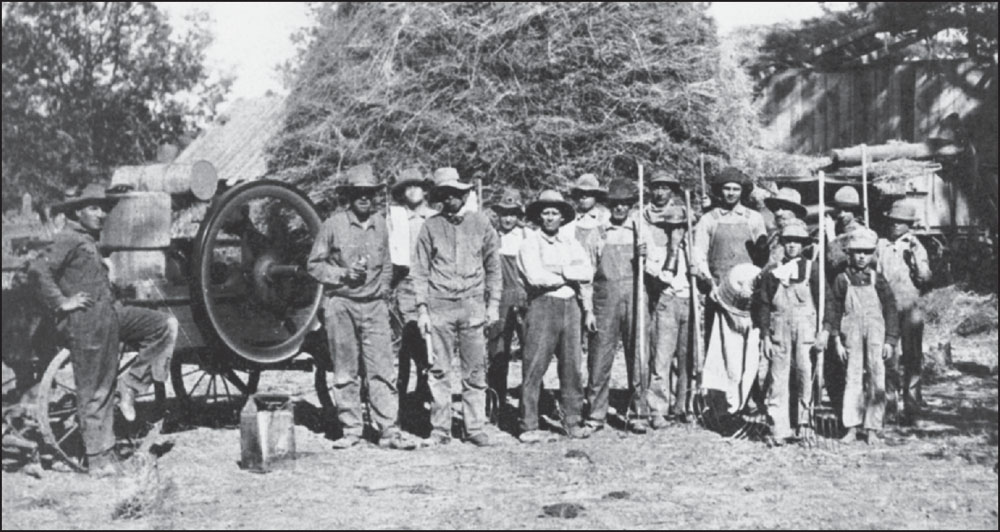

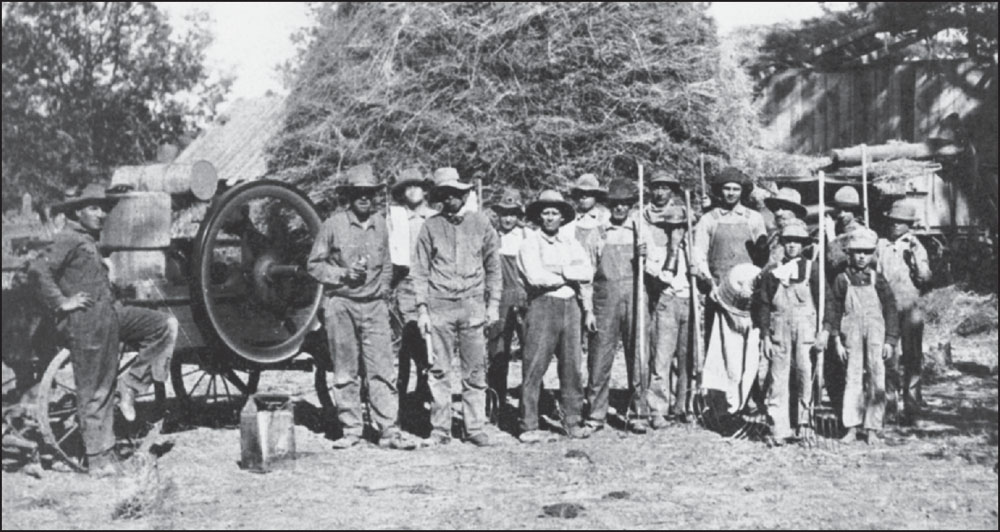

THRESHING CREW. All available hands in Lakeside helped with the threshing and stacking of silage in late summer. In rural communities, boys were excused from school to help with farm work. (Courtesy Marion Hansen.)

SHEEPHERDER AND PARTNERS. Sheep ranching remained an important part of the economy of the White Mountains in the first half of the 20th century. This photograph was taken in the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forests near Los Burros Campground, east of Lakside, in the 1980s. Sheep wintered in the Salt River Valley and were driven to mountain pastures for the summer by shepherds and their dogs. (Courtesy Juliette Aylor.)

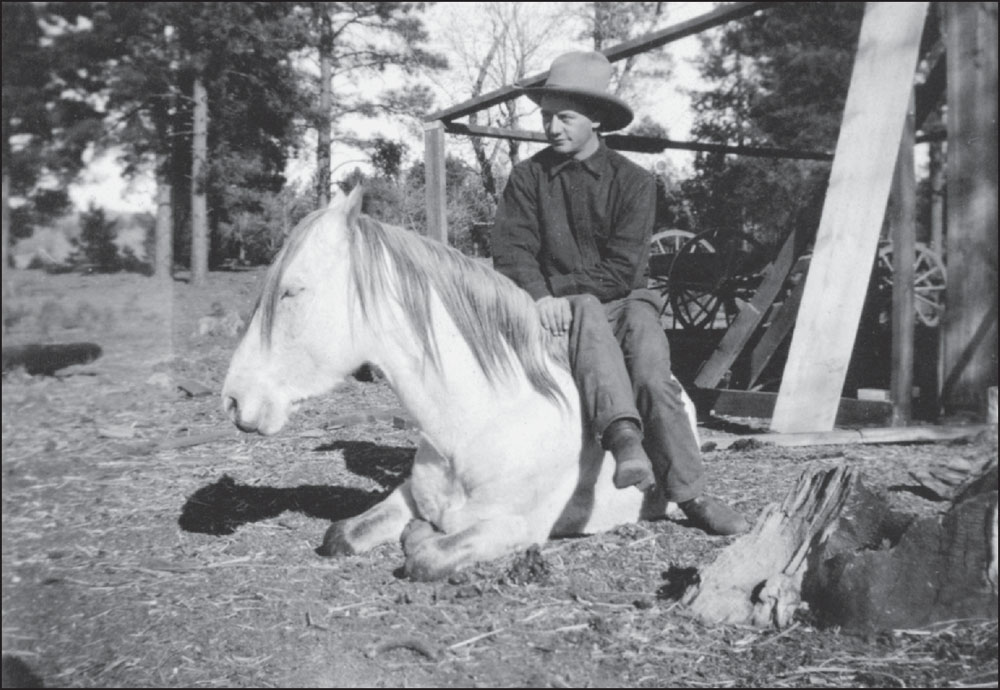

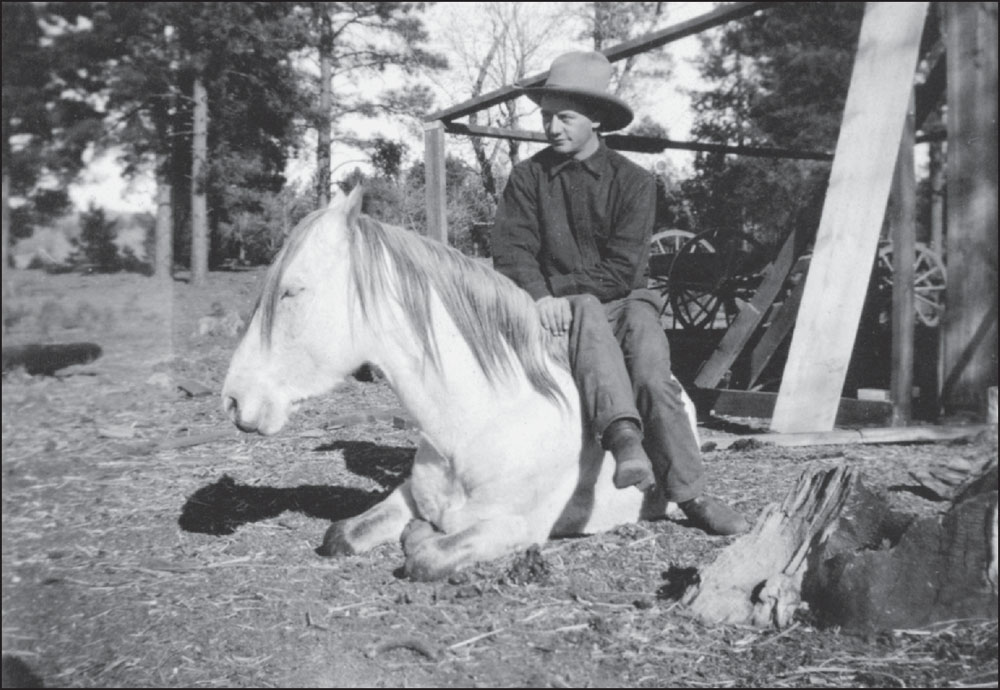

EARL WEST, 1920. West and his pet horse Dollie take time out from cowboying. West was a born horseman who liked to break broncs and train them, as well as ride them in rodeos. In 1916, when he was about 15, he and his brother Lavern caught and broke 125 wild horses for the White River Land & Cattle Co. (Courtesy Lonnie Amos West.)

EARL WEST AND ELSIE AMOS, 1921. Earl West is gallantly tying Elsie Amos’s shoelaces on the porch of the West Hotel. Later, they “tied the knot.” Elsie was the daughter of Belle Cooley Amos and Abe Amos, and the granddaughter of Corydon Cooley and Mollie. (Courtesy Lonnie Amos West.)

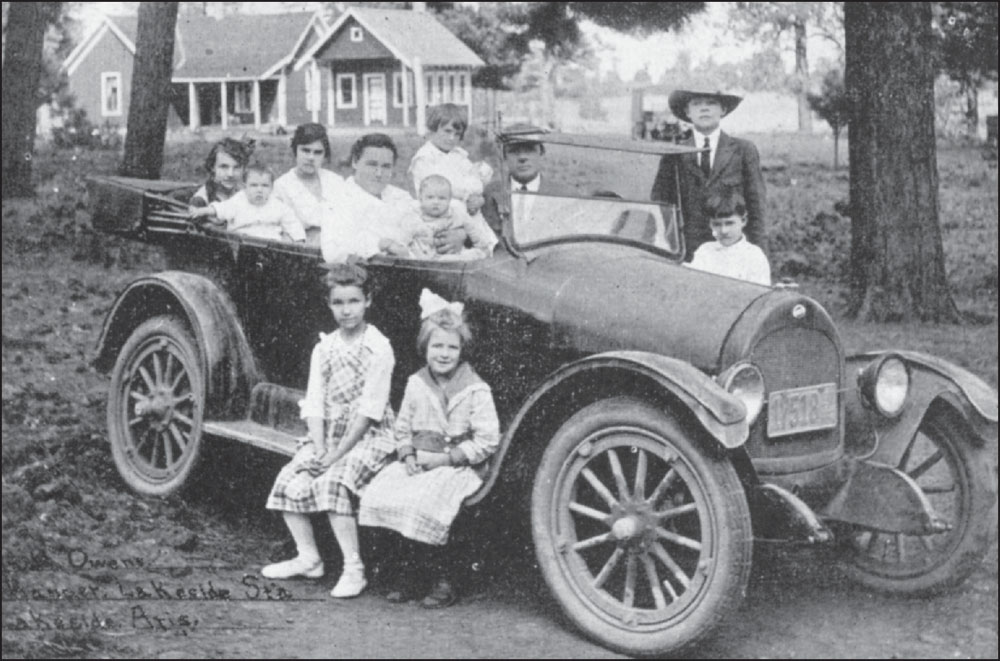

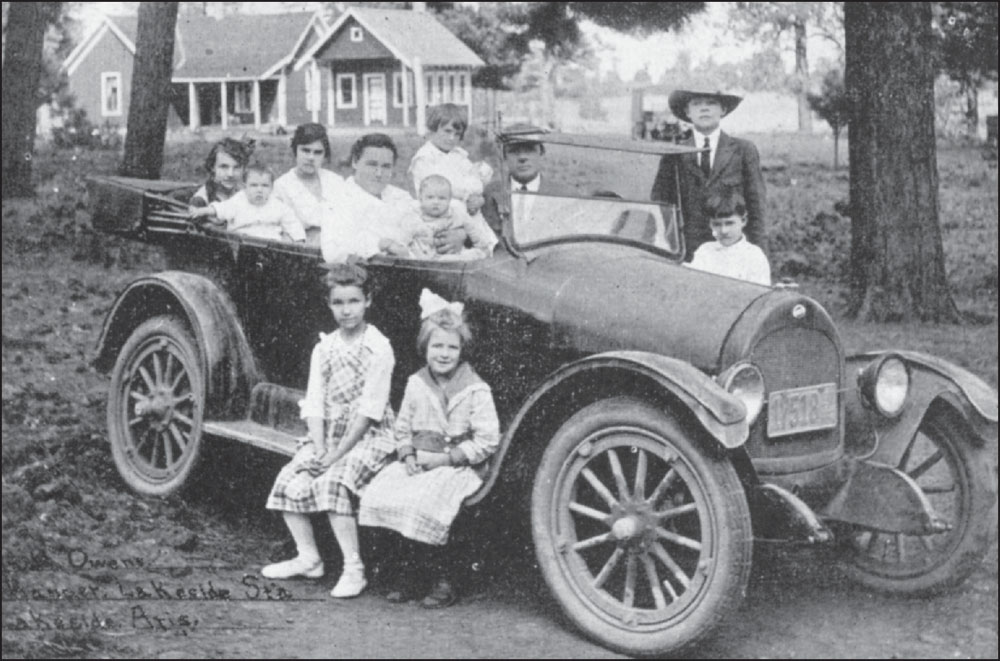

“HELD UP ON THE WAY TO CHURCH.” That was the title of this image in the 1918 Atherton Pamphlet. The people are unidentified, but the man in the big hat is believed to be Frank Owens, a Forest Service district ranger from 1914 to 1919, according to historian Ben Hansen. (Courtesy Marion Hansen.)

WEST HOTEL. In 1914, Lakeside pioneer Ezra West began construction of a large home that would also serve as a hotel. The two-story, 19-room building housed the family upstairs and accommodated guests downstairs. The family had many happy evenings and get-togethers around the fireplace in the big living room. It was the first and last hotel in Lakeside. By the 1930s, most travelers came by automobile and stayed in “auto courts.” (Courtesy Lonnie Amos West.)

WEST STORE. Ezra West’s son Joe built a store next to the West Hotel. The Pine Cone Garage and Grocery were run at various times by Ezra, Karl, Joe, and Lavern West. Here, they are showing off a fine string of trout caught in Rainbow Lake. Lakeside residents were becoming aware of the economic possibilities of tourism. (Courtesy Lonnie Amos West.)

BOY SCOUT TROOP ON MOUNT ORD, 1919. The leader is Phile Kay, in the upper right with the mustache, broad-brimmed hat, and rifle across his lap. From left to right are (lying on the ground) Milton Johnson, Roy Johnson, Rollin Fish, Tony Johnson, Roy Burke, and Dow Rhoton; (kneeling) Lloyd Rhoton, Neil Hansen, Donald Edwards, unidentified, and Lazelle Burke. (Courtesy Marion Hansen.)

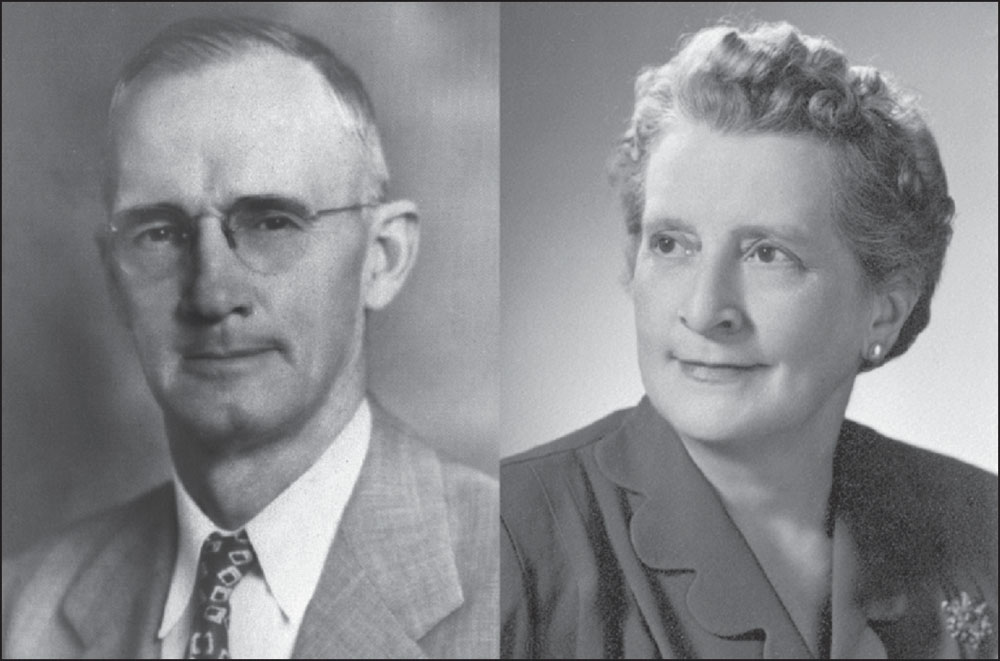

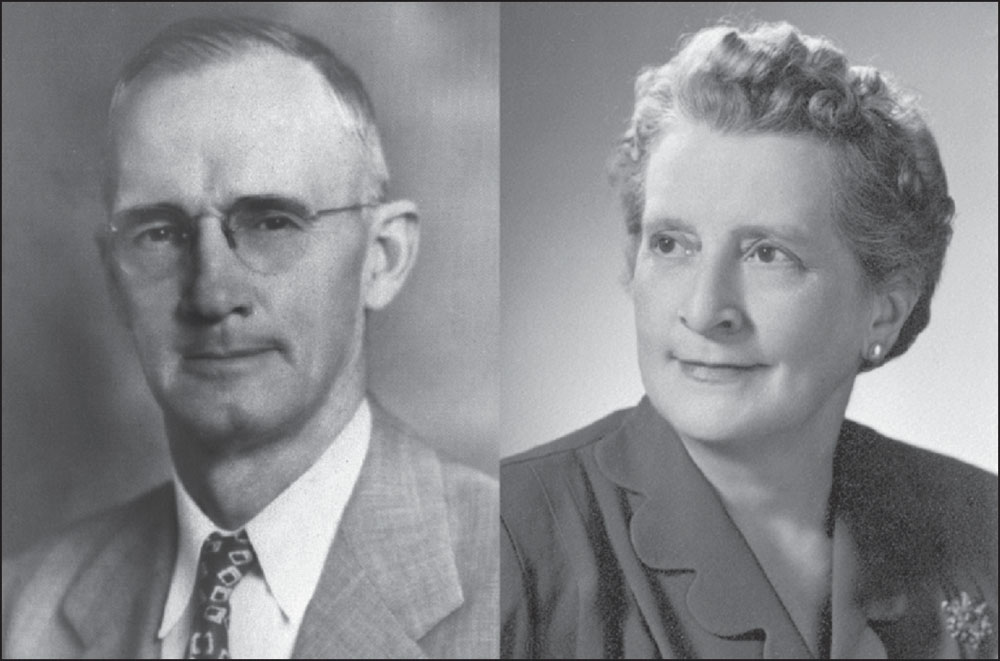

WALLACE AND AUGUSTA LARSON. In 1928, Ezra West, a school trustee, brought in excellent teachers for the little Lakeside school, including Wallace and Augusta “Gussie” Larson. Students could complete 10 grades, but to graduate from high school they had to travel 10 miles to McNary or board in Snowflake for their last two years. The first four-year graduation at Lakeside School took place in 1932. (Courtesy Lonnie Amos West.)

FIRST LAKESIDE SCHOOL BUS, 1937. Lakeside students did not have a school bus until 1937. Having a bus aided the development of sports programs. The first team sport in Lakeside was basketball, with practices held on a dirt court until a concrete pavilion was built next to the LDS church building. Students had no gymnasium until 1954–1955, when a gym was added on to the school building. The original school building burned down in 1957, but the gym was saved. It is presently on the end of the Pinetop-Lakeside town hall. (Courtesy Loretta Lee Jennings.)

JUNE MOON, 1928. These unidentified girls look as if they are still dripping wet. They probably took part in competitive swimming during the June Moon Water Festival of 1928. The festival was the largest in northern Arizona, and the area’s first serious attempt to promote tourism. Lakeside was publicized as “The Gardenspot of Arizona, a Paradise, and the Best Place of Outdoor Recreation.” All festivities revolved around Rainbow Lake, “the only lake in Arizona devoted solely to the giant Rainbow trout.” (Courtesy Marion Hansen.)

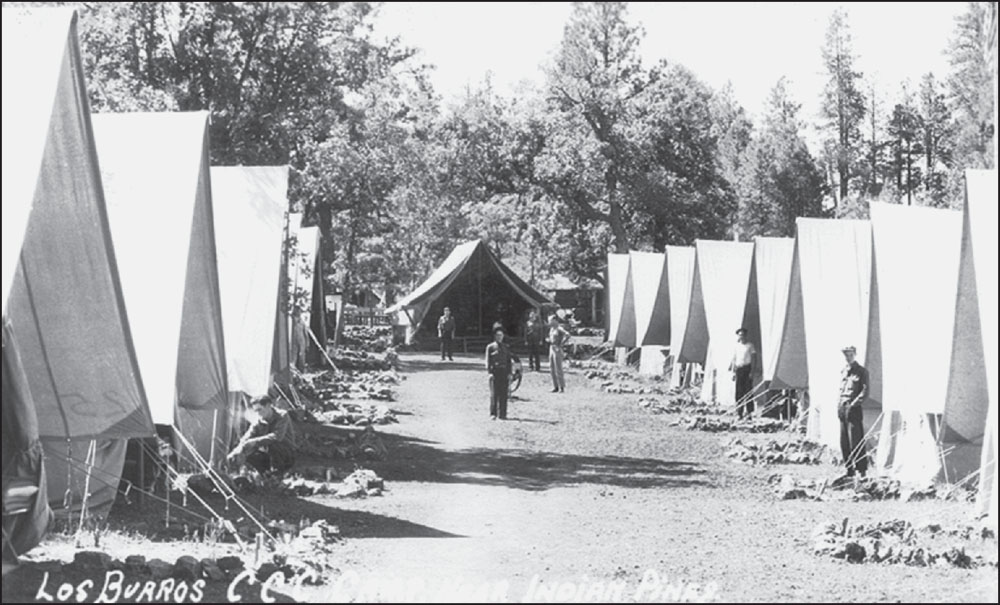

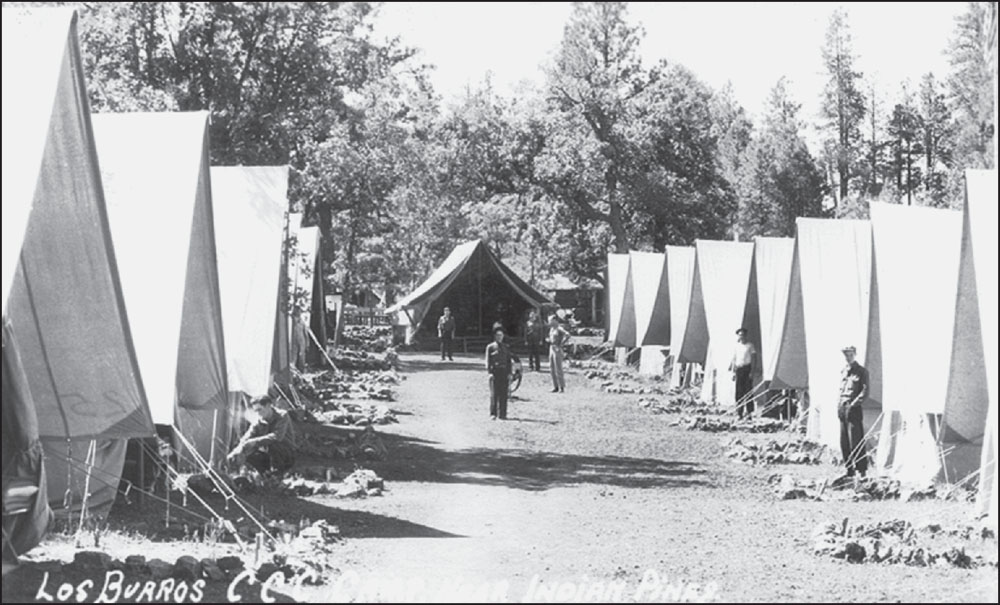

LOS BURROS CCC CAMP, 1933. Author Robert J. Moore wrote in The Civilian Conservation Corps in Arizona’s Rim Country: “This was camp F-22-A. The medical tent is at the head of the company street in this view.” Unmarried men aged 18–25 from all over the United States signed up for the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) in 1933. The program was part of Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, a response to the Great Depression. The program was designed to provide work for the unemployed and promote the conservation of natural resources. Los Burros Camp, one of the first four CCC camps in the Sitgreaves National Forest, was located in a wooded area south of Pinetop formerly known as the Welch Ranch. The CCC camp is not to be confused with a national forest campground also named Los Burros. (Courtesy Marshall Wood.)

CCC BUILDING FENCE. The Los Burros fence-cutting crew is building a fence for Lakeside Campground, across from the Lakeside Ranger Station. The CCC crews built forest roads and telephone lines to ranger stations and lookout towers. They also improved the old General Crook Trail (FR 300). They poured concrete for trout-rearing ponds at the Pinetop Fish Hatchery. At one point, the timber stand improvement crew of Company 823 was asked to supply peeled timber for the reconstruction of the Pueblo Ruins at Kinishba, near Fort Apache on the White Mountain Apache reservation. (Courtesy Marshall Wood.)

CCC MESS HALL, LOS BURROS. The first mess hall for Camp F-22-A was hastily constructed in the summer of 1933. Marshall Wood, who worked at the camp, remembered the room as “primitive and drafty.” He explained the after-meal routine to author Robert Moore: “Mess kits were scraped clean in a barrel, then washed through near-boiling soapy water before rinsing in hot clear water.” (Courtesy Marshall Wood.)

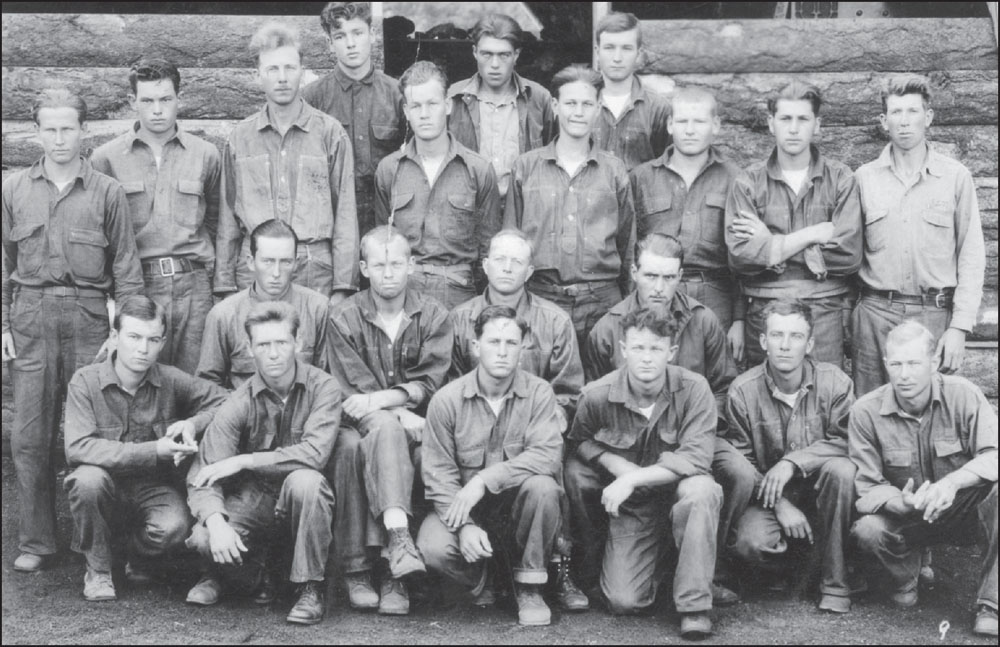

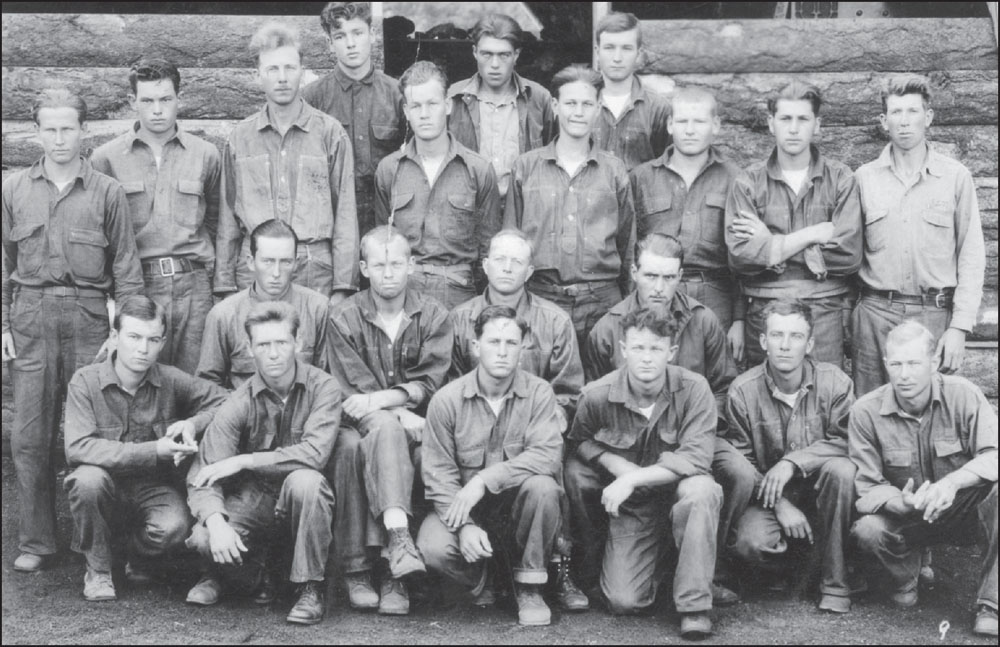

SATURDAY AT CCC CAMP. Men line up for a group shot on a Saturday morning in October 1933 in front of the company canteen. The man on the right is a Forest Service employee. In exchange for labor, men received food, clothing, shelter, and a monthly wage of $30, of which $25 had to go to a dependent family member of theirs. Los Burros CCC Camp was built on the present site of the White Mountain Country Club. (Courtesy Marshall Wood.)

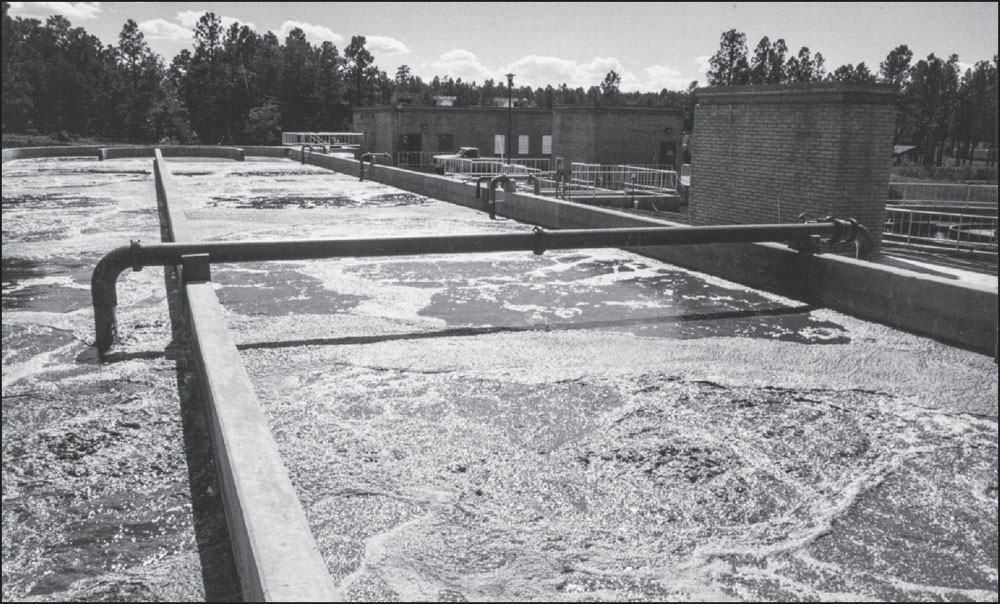

PINETOP FISH HATCHERY. The native fish population of the White Mountains, depleted by early settlers and soldiers, was a concern to territorial leaders who formed the Arizona Fish Commission in 1881. By 1929, the Fish Commission had evolved into the Arizona Game and Fish Department, which has legislative authority to regulate hunting and fishing activities. In the 1920s, the state began building hatcheries and planting trout. About 1932, a new hatchery was completed in Pinetop that became the major trout hatchery and rearing station for Arizona. (Courtesy Arizona Game and Fish Department.)

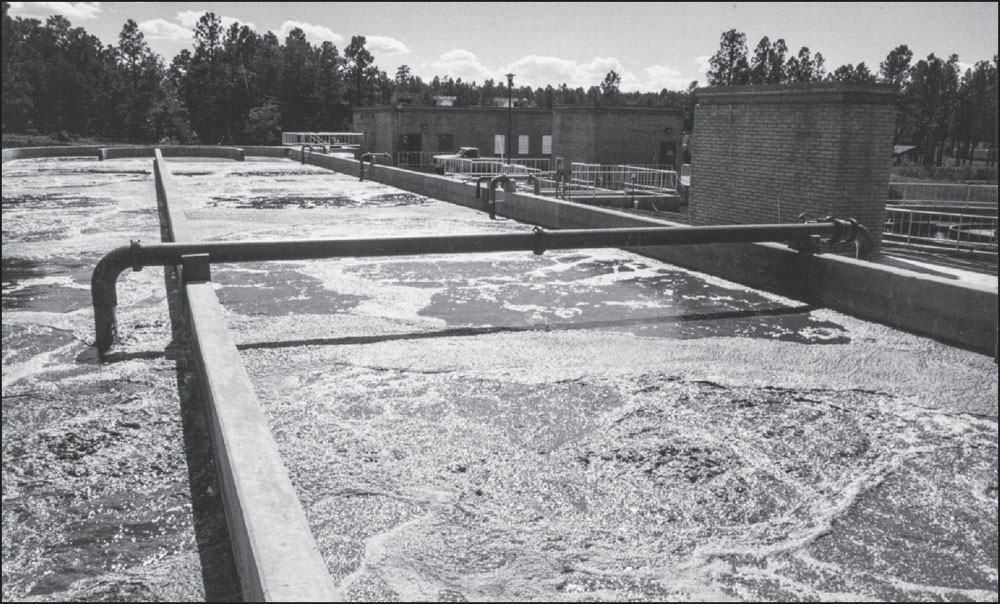

HATCHERY RACEWAYS. An ample supply of 52-degree water from Pinetop Spring allowed this facility to hatch up to three million eggs a year. Trout eggs were shipped in from as far as Yellowstone National Park. Most trout in the 1930s were reared to about five inches before they were planted in streams and lakes. Too many small trout did not survive, so larger trout were then grown before release. In 1941 the department began planting only creel-sized fish. Unfortunately, the water supply failed in the 1954 drought, and the department closed the Pinetop Hatchery. The redbrick building still stands near the Pinetop Regional Game and Fish Department Office. (Courtesy Arizona Game and Fish Department.)

STAN AND MART, 1931. George Stanley Stephens, son of Pinetop pioneers George and Harriet Stephens, was born in 1909 in a wagon while his dad was freighting between Pinetop and Fort Apache. He learned Apache and English simultaneously, growing up with Apache kids. He worked as a logger and then moved to Phoenix to try his hand at music. He could sing, yodel, and play the guitar, banjo, and fiddle. On Radio Station KOOL, he was known as “Mountain Steve.” Martha Elizabeth Welmon, known as “Mart,” fell in love with his voice. He married her in 1931 and brought her back to the mountains, where they raised their family. (Courtesy Bobbie Stephens Hunt.)

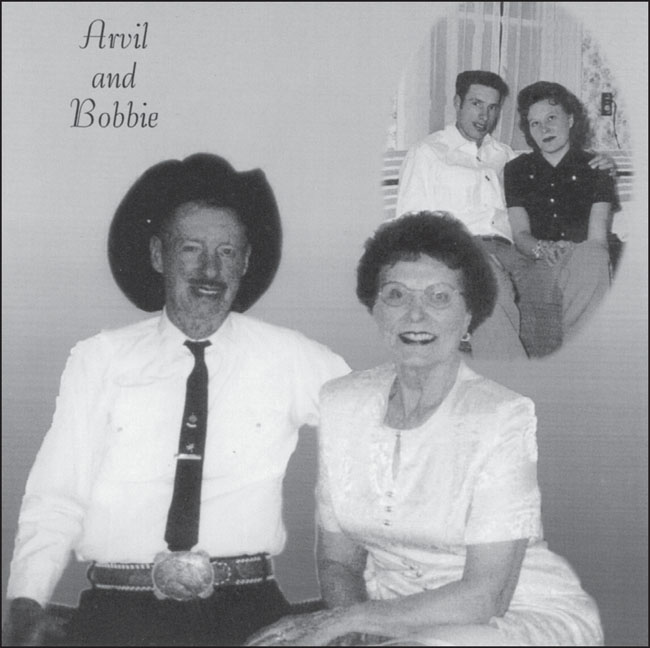

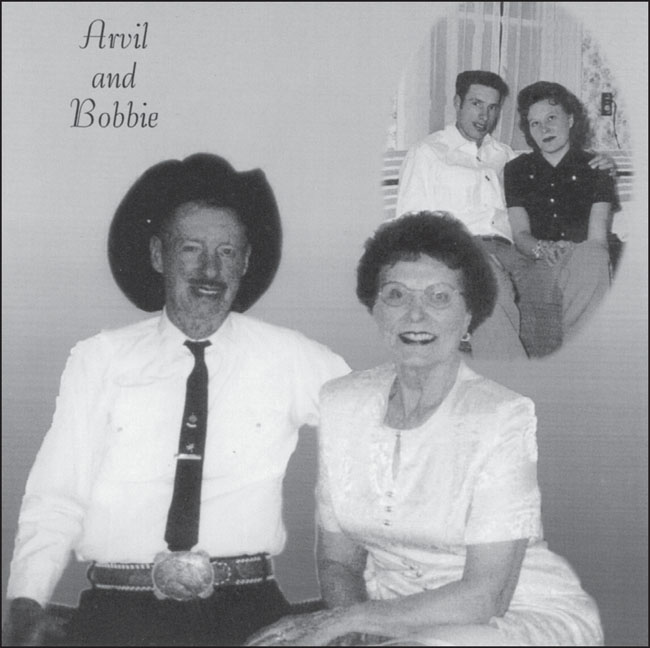

BOBBIE STEPHENS HUNT. Bobbie Stephens Hunt grew up in Pinetop and later moved to Maverick logging camp, where she met Arvil Hunt, an Oklahoma cowboy turned logger. On their first date, she playfully grabbed his new black Stetson hat. He warned, “You don’t mess with a cowboy’s hat.” She threw it in the log pond, so he threw her in the pond. They made up and have been married for more than 60 years. (Courtesy Bobbie Stephens Hunt.)

JAKE AND BLANCHE RENFRO. Ralph Thurston Renfro, nicknamed “Jake,” suffered all his life from the mustard gas he received serving in France in World War I. Sent to the Denver Veterans Hospital, he fell in love with his nurse. He and Blanche Ione Sanford were married and eventually settled in Pinetop, as they both loved the outdoors. During Prohibition, Jake, like many others, made and sold moonshine whiskey. With the repeal of Prohibition in 1933, he opened Jake Renfro’s Famous Log Cabin Café. Blanche did most of the cooking, and Jake did most of the fishing, so she said. They were known for sharing whatever they had with anyone in need. When a plane crashed on Mount Baldy, Jake and Blanche set up a base camp and cooked for the rescue party. In 1938, they sold the café to Charlie Clark. Jake died in Ajo in 1951 of a brain tumor and is buried in the Pinetop Cemetery. (Courtesy Gary Renfro.)

TURKEY HUNTERS. Local people as well as visitors have always come to Pinetop-Lakeside during hunting season. Holding their Thanksgiving dinners in front of Lisonbee’s store and gas station in Lakeside are, from left to right, Gilmore Jackson, Marion Hansen, and Gene Hansen. (Courtesy Renee Penrod.)

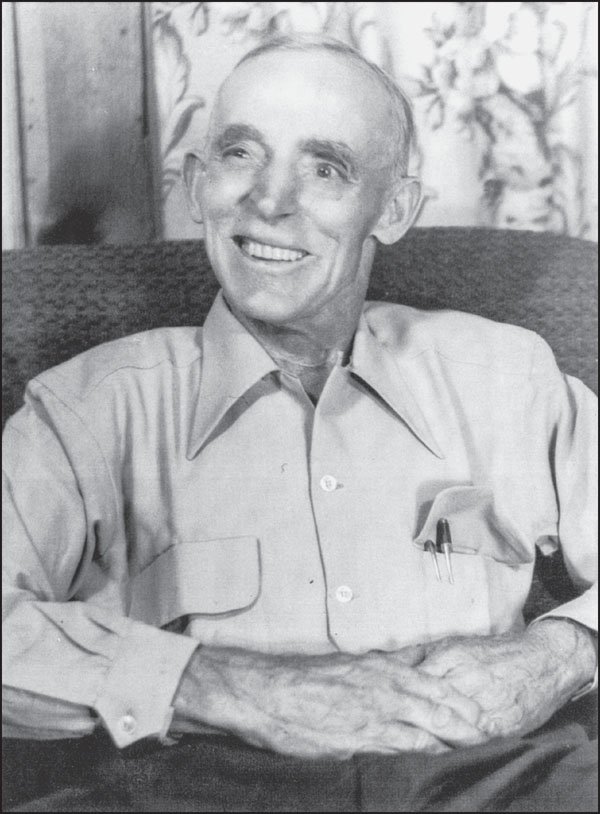

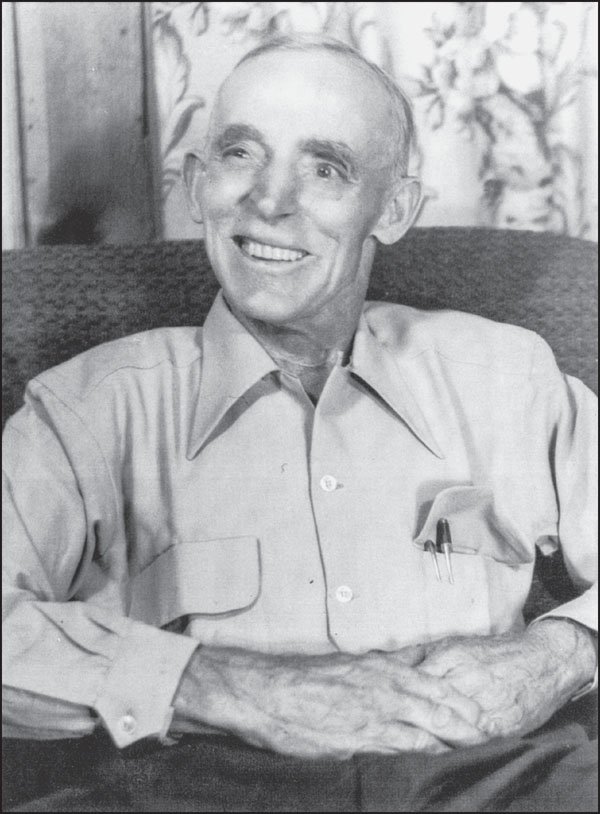

CHARLIE CLARK. Charlie Clark’s was a one-man operation much of the time, although he did have help from his daughters “Buddy” and “Dolly” when they were not in school. Buddy said they cleaned, washed dishes, and served food but were not allowed to serve liquor. One of her jobs was to roll quarters for customers who played the slot machines. Over the years, Charlie remodeled the restaurant, but he left the legendary barrel from which Jake Renfro pumped “white lightning” buried somewhere under the floor. (Courtesy Bill Gibson.)

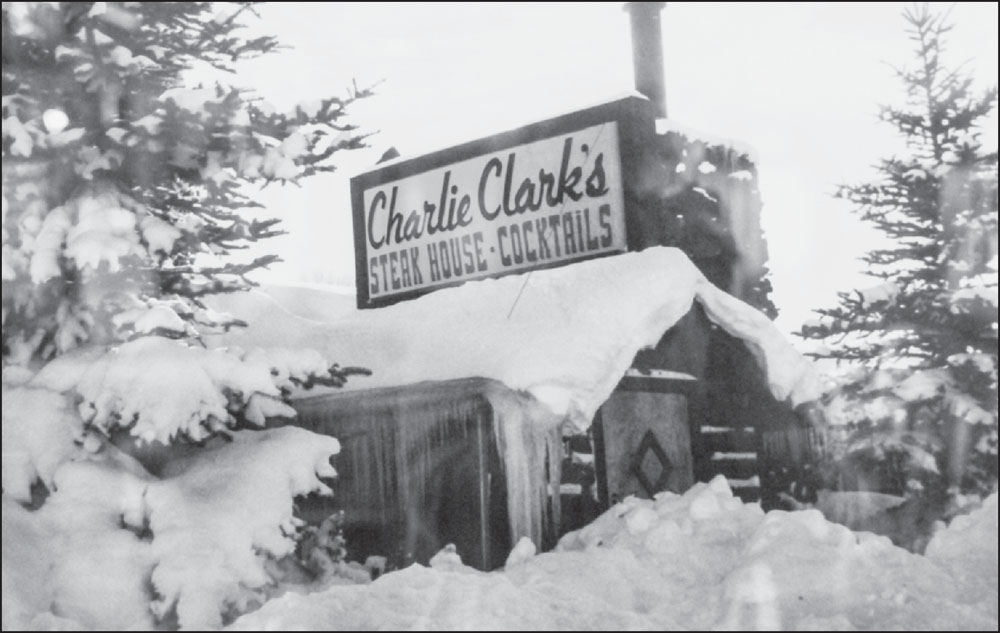

CHARLIE CLARK’S IN WINTER. Pinetop winters are not for sissies, but customers could always find a warm fire and warm welcome at Charlie Clark’s. By the 1950s, people who had never heard of Pinetop had heard of Charlie Clark’s, the oldest continually operating restaurant in Pinetop-Lakeside. Charlie passed on in April 1952. (Courtesy Bill Gibson.)

KIDS ON FLUME. The main irrigation ditch from Rainbow Lake to Show Low ran behind a ranch house belonging to Sanford Jaques. He built a flume to his house from the main ditch that brought freshwater to the house and made a swimming hole for kids. Jim Finney’s family lived there in 1939. Sitting on the edge of the flume with their feet in the water are, from left to right, Jack Cooper, Neil Finney, Annie Jo Finney, Hoax Cooper, and Scott Finney. (Courtesy Jo Ann Finney Hatch.)