Eight

TREES, TRAILS,

AND CONSERVATION

As early as 1881, the territory formed a three-man Arizona Fish Commission whose primary job was enforcing regulations. Residents and nonresidents were required to buy hunting and fishing licenses in 1912, the year of statehood. In 1929, the Arizona Game and Fish Department was established to manage wildlife and fisheries. A hatchery was built in Pinetop to raise trout to stock lakes and streams. Later, the US Fish and Wildlife Service had a Pinetop office to manage Alchesay and Williams Creek National Fish Hatcheries, on the White Mountain Apache reservation.

Fishing brought more revenue to Pinetop-Lakeside and the White Mountains than any other activity in the last century. By 1940, most Arizonans had cars, and many liked to spend summer vacations camping in the mountains. They bought food, gasoline, and fishing gear in Pinetop-Lakeside. Arizona Highways magazine showcased the splendor of the White Mountains to the world.

World War II had an impact on every American town, and Pinetop-Lakeside was no exception. Young men and women served in the military, resulting in a labor shortage at home. Gas rationing slowed the tourist trade. Food rationing affected restaurants. Conversely, the demand for lumber kept the McNary mill operating at full capacity. Following World War II, the mass migration to the Southwest resulted in a construction boom that ensured sawmills and lumber companies stayed in business.

The whole world opened up to Native Americans who served in the military. They learned new trades and skills and went to college on the GI Bill. They had access to veterans’ benefits and veterans’ preference in applying for government jobs. White Mountain Apache leaders looked for opportunities to become economically competitive. With nearly 1.7 million acres of prime forests and grasslands, the tribe began managing its own resources for its own economic benefit.

The tribe created lakes, campgrounds, and a summer home development around Hawley Lake. The Wildlife and Outdoor Recreation Division managed its own wildlife and instituted a world-class trophy elk hunt. The tribal purebred Hereford ID herd was considered one of the best in the country, and cattle brought high prices at fall auctions.

Fort Apache Timber Company was built by the tribe in 1963 to manage its own timber resources and provide employment for tribal members. The tribe built gas stations and convenience stores in outlying communities, a hotel, restaurant, and shopping center in Whiteriver, and the Hon-Dah Resort and Casino two miles south of Pinetop. The tribe’s Sunrise Park Ski Resort attracts skiers from northern Mexico and the Southwest.

As the tribe prospered, so did Pinetop-Lakeside. Tribal members spend money off the reservation in retail stores, restaurants, and professional offices. They drive “Up the Hill” to shop, see the latest movie, get their hair styled, or have a pedicure. Many tribal members live, work, and educate their children in Pinetop-Lakeside, while retaining their family and clan connections.

Pinetop-Lakeside has suffered two major disasters in the past half century. The first was a 1967 blizzard that dropped 8–10 feet of snow in a brief time, cutting off communications, electricity, and roads for four days. Neighbors helped one another, shoveling snow off roofs and sharing food and firewood.

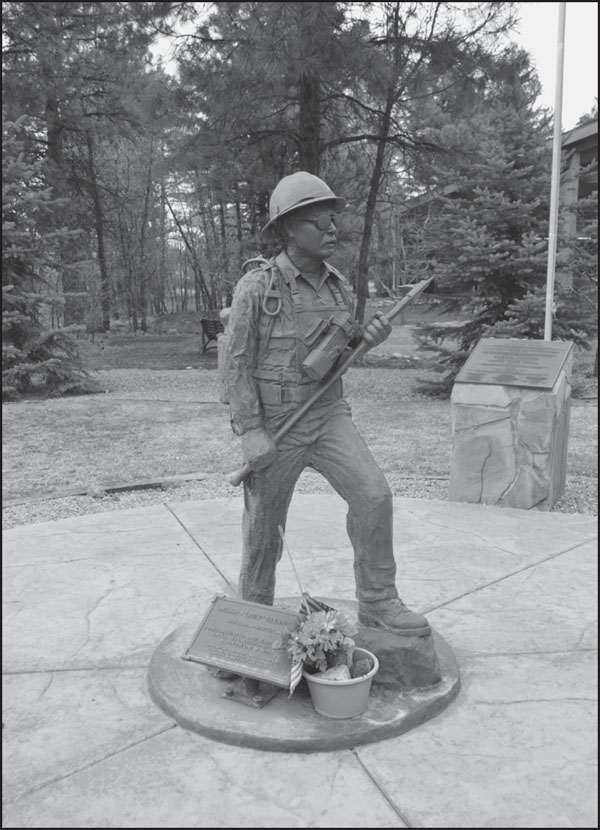

The second disaster was human-caused. The Rodeo-Chediski Fire of 2002 burned 468,638 acres along the Mogollon Rim. No deaths occurred, although 30,000 people were evacuated and more than 400 structures burned. Pinetop-Lakeside and Show Low were saved, largely because of the heroic efforts of Rick Lupe and two hotshot crews who conducted back-burns along Highway 60 to stop “the Monster” in its tracks.

The Rodeo-Chediski Fire proved that controlled burning of forests could prevent total loss. In 1950, BIA forester Harry Kallander of Pinetop advocated for controlled burning of portions of the forest in cool weather to reduce the fuel buildup that was causing large, destructive crown fires. In the 15 years Kallander was a BIA forester, crews control-burned nearly half of the reservation’s timbered lands. The effectiveness of controlled burning was validated when the Rodeo-Chediski Fire burned in a mosaic pattern, leaving islands of timber intact. Forest Service and BIA crews regularly conduct prescribed burns, as well as mechanically thinning small trees. Special attention is paid to Wildland-Urban Interfaces, where towns meet forests.

In recent years, Pinetop-Lakeside’s economy has leaned in the direction of outdoor recreation. With population growth in the 1980s came the threat of hikers and horsemen losing access to the forest from within the town. Volunteers worked with the town, property owners, and the Forest Service to create the White Mountain Trail System, which connects urban trails with national forest trails. Today, there are more than 200 miles of nonmotorized, multiuse, interconnecting trails for hikers, mountain bikers, horsemen, runners, and cross-country skiers. There are also trails for off-road vehicles.

The health of the forest is essential to the stability of ecosystems, the economy, and quality of life. The one element that unites all those who live on the mountain is the forest. The forest heals, supports, gives joy, and brings residents and visitors closer to nature.

SPRINGER MOUNTAIN LOOKOUT. Springer Mountain Fire Lookout overlooks the town of Pinetop-Lakeside. Lookouts, strung out across the forest, are the first line of defense against forest fires. Springer was one of the lookouts to spot the smoke of the Rodeo Fire on June 18, 2002. A second fire was spotted on Chediski Ridge later that day. The swiftly moving fires merged to become the Rodeo-Chediski Fire, the largest in Arizona history up to that time. (Courtesy USDA-Forest Service.)

ESCAPING “THE MONSTER.” Approximately 30,000 people from communities along the Mogollon Rim, from Forest Lakes to Pinetop, were evacuated during the Rodeo-Chediski Fire. This photograph was taken on the Deuce of Clubs in Show Low, showing cars headed east to shelters or friends’ homes in St. Johns and Springerville. (Courtesy White Mountain Independent.)

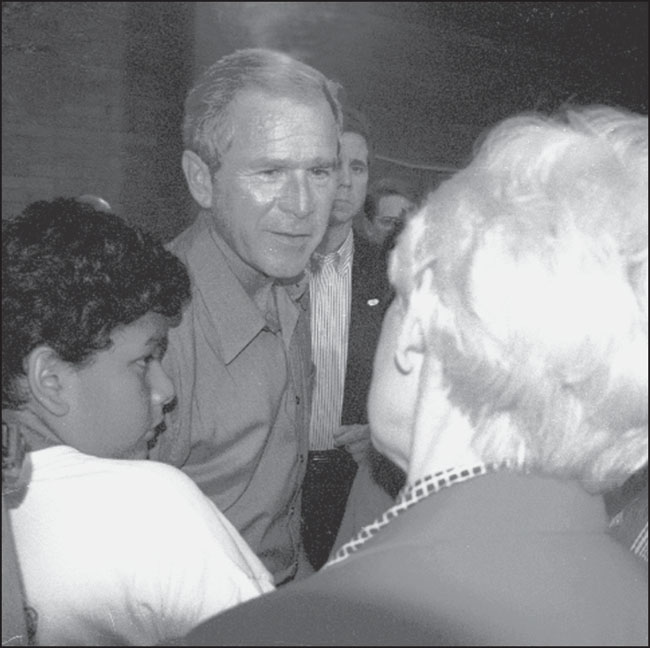

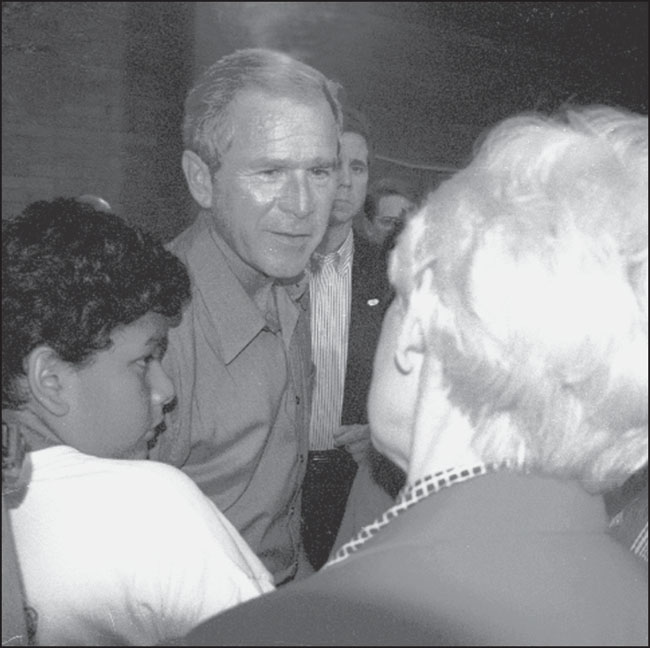

PRESIDENTIAL SUPPORT. Pres. George W. Bush arrived at the Springerville Airport on June 25, 2002, in a small jet aircraft with his sleeves rolled up. He had flown in secretly with Arizona governor Jane Hull to get the latest information on the fire and offer his support to firefighters and evacuees at the Round Valley Dome emergency shelter. In this photograph, the president is greeting Pinetop-Lakeside mayor Ginny Handorf. (Courtesy White Mountain Independent.)

SLURRY BOMBER. Air attack continued day after day, with lead planes circling and air tankers dropping fire retardant on whatever spot was targeted. The “slurry bombers” refueled at the air tanker base in Winslow and kept going as long as light held out. Helicopters and Single Engine Air Tankers were also used. (Courtesy USDA-Forest Service.)

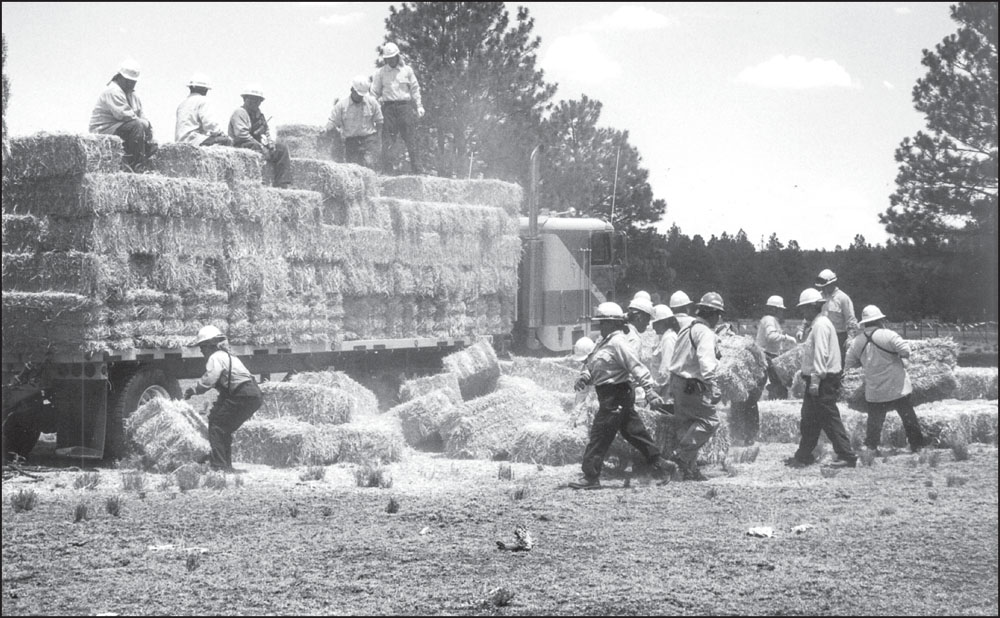

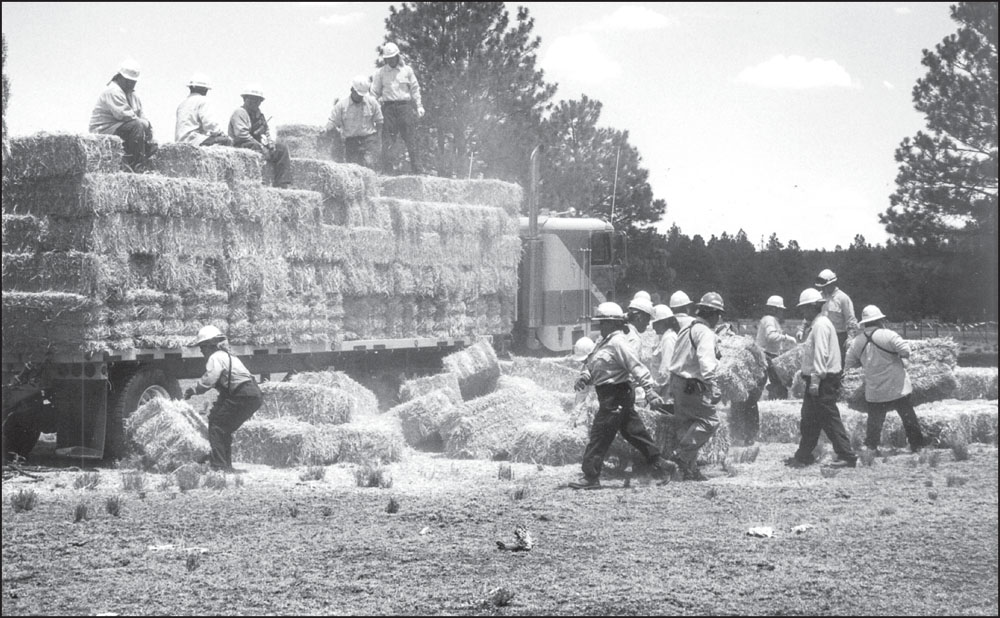

BALE BOMBING. Immediately following the Rodeo-Chediski Fire, the Burned Area Emergency Rehabilitation Team moved in to begin forest restoration. Tree and grass seedlings were scattered over the entire burned area, nearly half a million acres, from fixed wing aircraft. Next, the area was “bombed” with straw bales thrown out of a helicopter. The bales broke apart in the air and scattered over the seedlings to protect them from erosion. Here, an Apache crew is loading hay bales. (Author’s collection.)

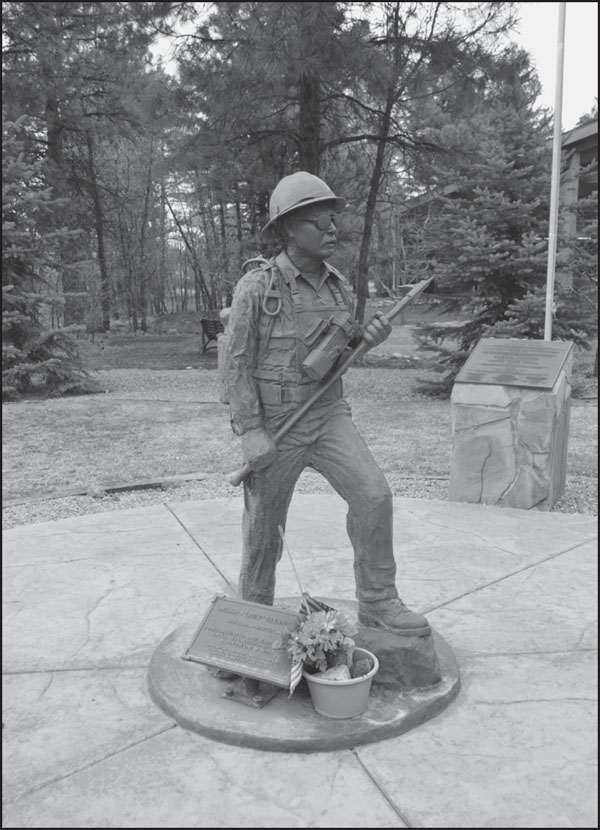

STATUE TO A HERO. Eagle Scout Richard Genck raised money to fund this statue of White Mountain Apache firefighter Rick Lupe. The plaque at the base of the statue reads, “Richard ‘Rick’ Glenn Lupe, May 18, 1960 – June 19, 2003, A true American hero recognized as one of our Nation’s greatest firefighters, died in the line of duty. ‘Little do they know of our long labors on their behalf for the protection of their borders. And yet, I grudge it not.’ – J.R.R. Tolkien.” (Courtesy Judi Bassett.)

COMPOSTING DIGESTER. The Pinetop-Lakeside Sanitary District was formed when the Environmental Protection Agency compelled the town to replace its individual septic tank system with a municipal sewer system by denying new permits to developers. Ground percolation was so poor that leech lines were polluting Billy Creek and shallow groundwater. In 1976, the sanitary district board contracted with Lowry & Associates to build a state-of-the-art, environmentally sound wastewater disposal system. This photograph shows the original digester that chewed up biosolids and made compost. Operating engineer Phil Hayes said, “We have had people from all over the world come here to study the system.” (Courtesy Pinetop-Lakeside Sanitary District.)

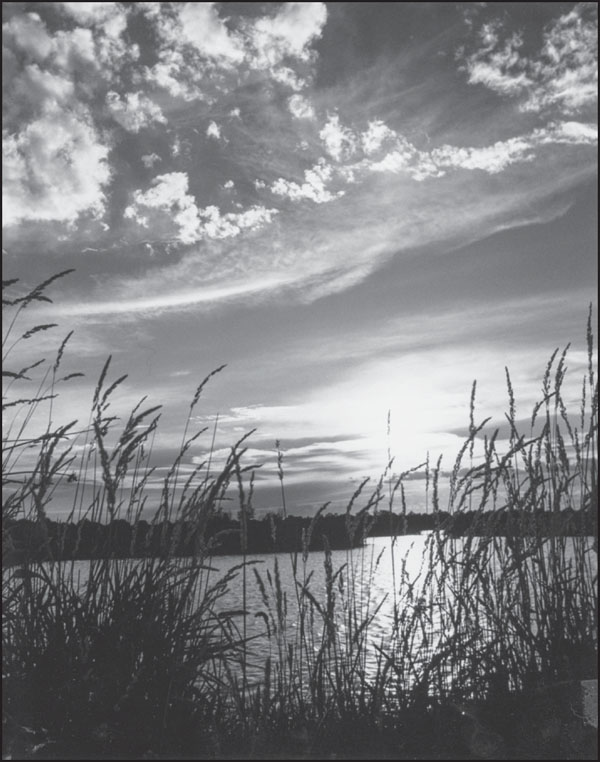

JAQUES MARSH. Through an innovative plan that involved the sanitary district, the town, the EPA, the Forest Service, and the Arizona Game and Fish Department, wastewater is now treated, aerated in ponds at the plant, and run through national forest lands to a series of man-made ponds and marshes to create a wetland habitat for waterfowl and other wildlife. (Courtesy Pinetop-Lakeside Sanitary District.)

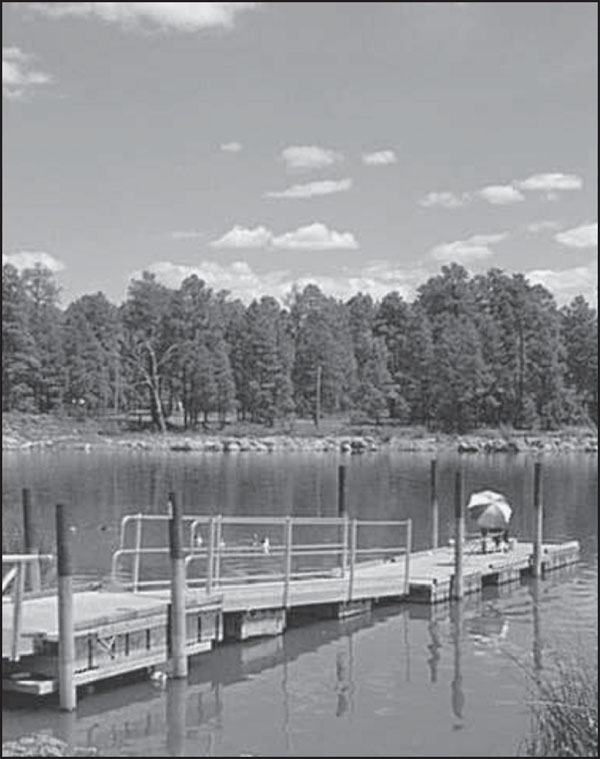

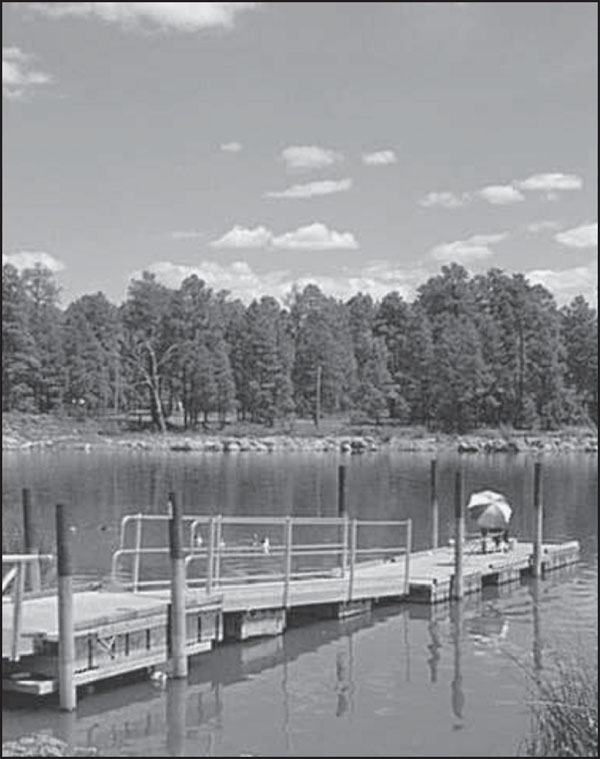

WOODLAND LAKE PARK. The 580-acre parcel of forest, woodland, marsh and lake in the heart of Pinetop-Lakeside is used and cherished by those who love the outdoors. Developed by the Forest Service, the town, and volunteer groups, the park offers tennis courts, softball fields, volleyball courts, hiking, mountain biking, and equestrian trails, fishing, boating, picnic ramadas, charcoal grills, restrooms, playgrounds, and bird-watching opportunities. Big Springs is under a special use permit to the Blue Ridge Unified School District for an environmental study area. The land is owned by the national forest, but partners in management are the school district, the Arizona Game and Fish Department, the Town of Pinetop-Lakeside, and White Mountain Wildlife and Nature Center Inc. (Courtesy Jack Wood.)

HORSEMEN’S REST. In 1987, a group of 25 local horsemen met to discuss what to do about trail closures within the town as development increased. They decided to form the White Mountain Horsemen’s Association (WMHA) and unite in an effort to create a series of multiuse, interconnecting loop trails from Vernon in the east to Clay Springs in the west. Businessman Jerry Handorf did most of the mapping, designing, planning, and organizing, with the help of Bev Garcia and others. The Forest Service approved the proposed trail system in 1989. Jerry’s initial work with the WMHA led to the development of the 200-mile White Mountain Trail System. (Courtesy Bev Garcia.)

TRAIL BLAZERS. TRACKS is one of the hardest-working groups on the mountain. The volunteer organization is dedicated to using, promoting, preserving, and protecting multiuse, nonmotorized trails throughout the White Mountains. TRACKS also participates in community events, such as National Trails Day, Tour of the White Mountains, and the fall “leafing” hike and pot luck. Members meet for breakfast and do weekly trail maintenance throughout the White Mountains. (Courtesy Judi Bassett.)

NATURE CENTER. The Nature Center, on Woodland Road, is an outgrowth of Mary Ellen Bittorf’s love of nature and animals. Children and adults come to hear talks on wildlife by experts. This owl is probably a visitor from the Adobe Mountain Wildlife Center in Phoenix, which cares for and rehabilitates injured wildlife. (Courtesy Judi Bassett.)

GINNY HANDORF. Handorf was mayor of Pinetop-Lakeside during the Rodeo-Chediski Fire. She and her husband, Jerry, have been active in many community affairs along with operating a small business. Among her many accomplishments, Handorf sings with the White Mountain Chorale, is choir director for St. Mary of the Angels Catholic Church, has organized drama groups and productions, and served on the board of directors of Northland Pioneer College. (Courtesy Handorf Family.)

BIRD WATCHING. The White Mountains are home to many species of birds, from migrating waterfowl to bald eagles, ospreys, and all colors and sizes of songbirds. The White Mountain Audubon Society holds monthly meetings, participates in bird counts, and is dedicated to providing environmental leadership and awareness through fellowship, education, community involvement, and conservation programs. (Courtesy USDA-Forest Service.)