INTRODUCTION

For longer than anyone can remember, people who love the outdoors have called Arizona’s White Mountains “God’s Country.” In modern times, they come in waves to fish, hunt, camp, hike, and backpack, ride ATVs, snowmobiles, and horses, scale mountains and canyons, golf, ski, cut Christmas trees, bird-watch, observe wildlife, and take pictures. They come to restore their souls in the pine-laden air.

The town of Pinetop-Lakeside is a gateway to this mountain paradise. Approximately 4,200 people call the incorporated area home, but cabins and country clubs are scattered throughout the surrounding forests and woodlands. For a small town, the population is surprisingly cosmopolitan. People congregate at barbecues, chili cook-offs, festivals, art shows, concerts, and sports events. They come to eat, drink, and converse at one of many good restaurants. Scarcely a week passes without a public benefit of some kind. Mountain people help each other.

Those who live here call it simply “the mountain.” They live and work and grow old by the seasons. They live on the mountain because they want to. It is not unusual to find a fifth-generation descendant of a pioneer family living here. They go away, but they come back.

Pinetop-Lakeside is the headquarters for the Lakeside Ranger District of the two-million-acre Apache-Sitgreaves National Forests, whose lands range in elevation from around 6,000 feet in the piñon-juniper woodlands, to forests of pine, spruce, and fir on the 11,400-foot-high Mount Baldy. The “A-Bar-S,” as it is known locally, nurtures 24 lakes and reservoirs and more than 700 miles of trout streams.

The southern boundary of Pinetop-Lakeside borders the Fort Apache Indian Reservation, the traditional homeland of the White Mountain Apache Tribe. The 1.6-million-acre reservation was once much larger, including land now belonging to the town. The past, present, and future of reservation and off-reservation communities are intertwined. Tourists fish and camp on tribal lakes and streams, hunt trophy elk, ski at Sunrise Resort, dine at Hon-dah Casino and Convention Center, and work, teach, and drive on tribal lands. Tribal members shop, eat out, work, go to movies, attend school, and often live in Pinetop-Lakeside. Tribal and non-tribal law enforcement, as well as fire and emergency services, work together under cooperative agreements.

Humans have left their footprints in these mountains for as long as 14,000 years. Ancient hunters passed this way. Except for stone artifacts and signs of campsites, the hunters left no trace. The first distinct culture archaeologists recognize in the White Mountains is known as “Mogollon.” These ancestors of Hopi and Zuni people cultivated corn, beans, squash, and sunflowers, domesticated wild turkeys, and made pottery. They traded with people as far away as Central America and California. By 1450 a.d., they had moved on. Archaeological evidence suggests that Athabaskan-speaking people began to drift into the Southwest in small bands from the north around the same period that the Ancestral Pueblo people left.

The first known presence of Europeans in the White Mountains was Francisco Vazquez de Coronado’s expedition, which left New Spain in 1540 in search of the fabled Seven Cities of Cibola. Stewart Udall, in his book In Coronado’s Footsteps, claims Coronado crossed the Gila River, then climbed a tortuous ascent north into the White Mountains through or near the present communities of Whiteriver, Pinetop-Lakeside, and McNary on his way to Zuni Pueblo. The Spanish conquest and colonization of the Americas brought gifts to indigenous people, as well as suffering. Once Navajo and Apache people adopted a horse culture, they impeded the settlement of northern Arizona for 250 years.

Five major historical events affected the colonization and environment of the Pinetop-Lakeside area: the introduction of horses, cattle, and sheep by Hispanic and Anglo ranchers; the establishment of Fort Apache by the US military; the completion of the Atlantic & Pacific Railroad across northern Arizona; the creation of the US Forest Service and the beginnings of a timber industry; and the gradual shift to an economy based on outdoor recreational tourism.

Sheepherders from Spanish colonial New Mexico were driving bands of livestock into northern Arizona by the 1850s, but they did not colonize the mountain country until much later. They practiced transhumance, driving their flocks to summer camps in the mountains and then back to lower country in winter. Cattlemen began to drift into the White Mountains after the Civil War. They were a venturesome breed and a law unto themselves. Men came on ahead, scouting out locations and building crude cabins before they sent for their families.

Mountain families were poor in worldly goods until Fort Apache was established in 1871. The remote Army outpost provided protection for both white settlers and Apaches, as well as a ready market for hay, grain, beef, and fresh produce. The new post created work for freighters, skilled craftsmen, and laborers. More than any other factor, the presence of Fort Apache opened up the White Mountains for settlement.

In 1873, the White Mountains were surveyed, mapped, and explored by the US Corps of Topographical Engineers. Cartographer Lt. George M. Wheeler stood on the top of Mount Baldy on a summer day and wrote, “Few worldwide travelers in a lifetime could be treated to a more perfect landscape, a true virgin solitude, undefiled by the presence of man.”

Corydon Eliphalet Cooley came to Arizona as a prospector in 1869, then stayed as an Army scout and rancher. Married to two of Chief Pedro’s daughters, he was largely responsible for maintaining peaceful relations between Apaches and white settlers in the White Mountains. Other pioneer ranchers in the Pinetop-Lakeside area included Will Amos, William Morgan, the Scott brothers, and Jim Porter. They ran sheep and cattle on public-domain lands and on the Apache reservation.

Brigham Young sent wagon trains of Latter-day Saints down the trail from Utah to colonize the Little Colorado River Valley in the late 1870s. They bought out many of the earlier settlers and organized true communities with schools, churches, and cooperative mercantile stores, built dams and irrigation systems, and raised crops and cattle. In spite of enduring extreme hardships and years of cruel persecution, they prevailed, and they maintain a strong influence in today’s culture.

In 1881, the Atlantic & Pacific Railroad came rumbling into Holbrook, 60 miles north of Pinetop-Lakeside. Many of the early mountain people made a living supplying railroad crews with beef and elk meat, or by cutting trees for railroad ties. More significantly, a lucrative freighting business between Holbrook and Fort Apache was established to supply feed and supplies to the army.

When the heyday of large corporate cattle ranches in northern Arizona came to an abrupt halt near the turn of the 20th century, new economic opportunities arose in the mountains. Arizona’s Mogollon Rim is a steep, 200-mile-long escarpment that juts up from the desert floor to the mile-high Colorado Plateau and runs diagonally across the state from northwest to southeast. Arizona’s high country nurtures the largest continuous stand of ponderosa pine in the world. Small sawmills provided a living for many mountain families in the early days of settlement. The next century saw the rise of a timber industry.

Statehood for Arizona had not yet come to pass in 1905 when the US Forest Service was established. World War I raised the demand for lumber, and the national forests were called on to help meet that demand. The federal government offered timber sale contracts to stimulate commercial logging. Entrepreneurial banker Tom Pollack of Flagstaff saw a fortune in trees. Pollack and his partners built the Apache Railway from Holbrook to their new sawmill near Cluff Cienega, in the midst of the vast pine belt of east-central Arizona. The town they called Cooley was later renamed McNary after James G. McNary, one of the partners in the Cady Lumber Co. of Louisiana. The company reorganized several times, and was known as Southwest Forest Industries until it shut down.

The US Army left Fort Apache in 1922, with the remaining cavalry troopers and Apache Scouts moving to Fort Huachuca in southern Arizona. A Bureau of Indian Affairs boarding school was constructed at the old fort. It continues to operate as Theodore Roosevelt School today. The former cavalry outpost is now Fort Apache Historic Park, the home of the White Mountain Apache Cultural Center and Museum, which preserves the culture and language of the White Mountain Apache people.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the White Mountain Apache Tribe created a recreation enterprise, building lakes, campsites, stores, and roads in its goal of becoming a major economic force in the region. At the same time, Pinetop-Lakeside developers began selling lots for summer homes, country clubs, and RV parks. The tribe, the USDA-Forest Service, the Arizona Game and Fish Department, and the Town of Pinetop-Lakeside have worked together for the past half century to manage natural resources and promote economic development. Cattle ranching and forest products industries still flourish in the White Mountains, but tourism is the major source of revenue for Pinetop-Lakeside. It is primarily a resort and retirement center. In addition to a 200-mile-long system of interconnected, multiuse forest trails, residents have easy access to a regional medical center, a regional airport, a community college, museums, libraries, art galleries, and large retail stores.

To visit Pinetop-Lakeside is a weekend adventure. To live on the mountain requires a certain mindset. Those who value quality of life over income, nature over design, and stars over bright lights live with pride in their lifestyle and history. The community runs on volunteerism. The spirit of community still underlies all of life in “God’s Country.”

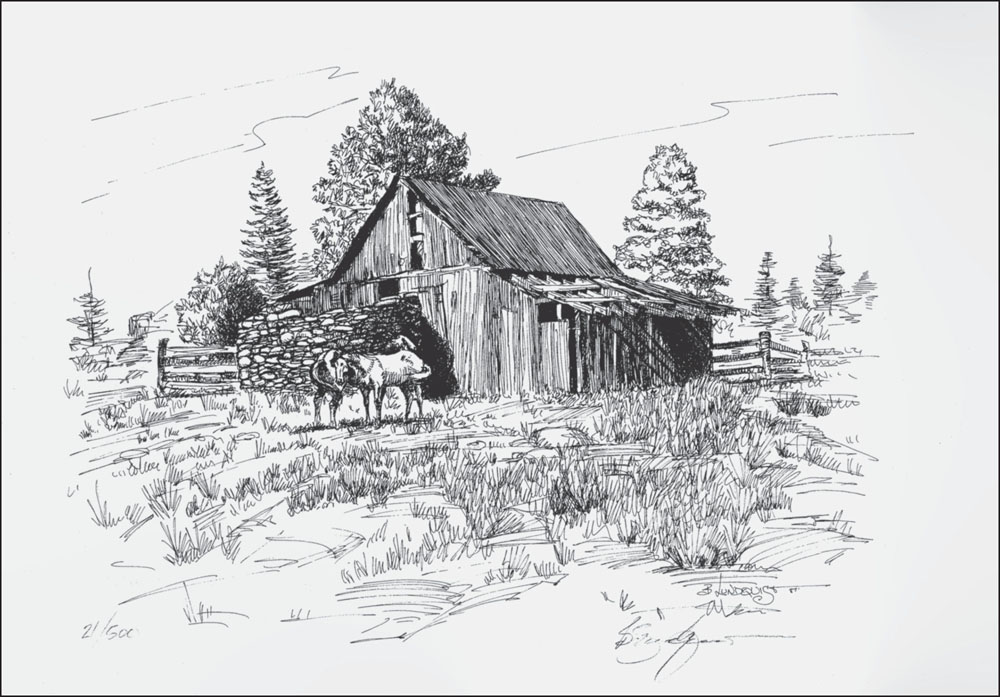

RHOTON BARN. The Rhoton barn, in Lakeside, was an iconic landmark for decades, painted and sketched by artists and photographed by nearly every tourist passing through. It was part of the Rhoton Dairy, which was owned and operated by Charles Lowe Rhoton, his wife, Louise, and their two sons, Dow and Royal, in the 1920s. Bill Lundquist, an Arizona artist who was the vice president and manager of the First National Bank in Pinetop from 1985 to 1992, made this sketch. (Courtesy Bill Lundquist.)