An old Spanish proverb tells us that he is always right who suspects he makes mistakes. The ten mistakes that I will discuss in this chapter are those commonly made in genealogical research. For those of you who think these mistakes are too obvious to belong in an advanced methodology book, be aware that most good genealogists have made and will continue to make these mistakes. It is only by being wary and constantly on the lookout that we can avoid falling into these traps.

The mistakes described in this chapter may make us laugh, not only because we may recognize ourselves and our colleagues in them, but because we are all human and humans do humorous things. As we discuss common research errors, no one should feel singled out for doing something foolish. We all follow the same patterns, and we’ve all committed the same types of errors. There is nothing wrong with making mistakes. The trick is to treat them as learning experiences so we can avoid doing the same thing again.

The census is most often recommended as the initial source for beginning genealogists. It is readily available and likely to contain good information about our ancestors. Problems may arise, however, if you begin to use the census exclusively, or depend on it as your sole source of information for establishing family connections. Remember that the census provides only a skeleton for our research; we will have to search other records for the muscle, tissue, and vessels we need to reconstruct our ancestors’ lives.

In addition to the census, beginning genealogists usually rely on birth and death records—those wonderful registries of vital statistics that became readily available during the twentieth century. If you have found one of those informative death certificates that lists the birth date and place of the individual who died, the names of his parents and their birthplaces, as well as his mother’s maiden name, you know that great amounts of information may be contained on that one little piece of paper. Birth records may be just as rewarding—but beware of becoming too dependent on those vital certificates. They are useful as you begin to identify the families from which you descend. But what will happen when you need to trace an ancestor who was born in Kentucky around, say, 1880? You send for a birth certificate, only to be told that no vital records for that period exist. If you’ve come to depend on such documents for all of your information, you are stuck.

Probate records are another source that genealogists quickly learn to depend upon. After checking the census and determining that an elderly person moved into a particular region and then disappeared, we often assume that he died there. The next thing we do is send for a will. If there is no will, research grinds to a halt. But if we do find a will and the ancestor that we are looking for is named among the children of the decedent, we’ve got it. Parent, child—right? Must be the same guy!

Or was he? Individuals who left wills always seem to end up with many, many, many children that they never had in real life. It’s too easy to assume that the man named in the will is one’s ancestor. Lots of people from many branches of the family may assume the same thing. For example, Christian Newcomer of Manor Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, left a will in 1805 in which he named his sons John, Christian, Peter, Abraham, and Jacob. His daughters were Ann, Barbara, Elizabeth, and Magdalene. Probably every person who ever had ancestors named Newcomer living in Lancaster County has tried to attach his own John, Christian, Peter, Abraham, Jacob, Ann, Barbara, Elizabeth or Magdalene to that will, because that particular Christian Newcomer has had at least seventy-two children assigned to him by different genealogists.

Some fundamental mistakes that may occur when we use exclusively census and probate records include confusing people of the same name, overlooking people who appeared and disappeared again between censuses, and assigning children to families to whom they do not belong. To avoid these errors, consult other documents such as circuit court minutes, other kinds of court records, tax records, deeds, veteran’s benefits, guardianship records, and newspapers. Don’t confine your research to just one source, even if it seems to be a very helpful one. Look at everything you can possibly find.

The late, well-known genealogist Milton Rubincam often referred to those distressing people once believed—erroneously—to be part of his pedigree as “my former ancestors.” Further research may indicate that you must prune some perfectly wonderful people from the branches of your family tree. From time to time, probably all of us will have to rethink, reanalyze, and even redo our research.

George Morgan of Wayne County, Pennsylvania, married a widow named Deborah Headley about 1802. I was trying to find her maiden name. Preliminary research indicated there were several Hoadley families living in the area, and since my information had come from a Daughters of the American Revolution application, I thought it possible that a mistake had been made with one letter and that I actually should be looking for Hoadleys instead of Headleys.

The Wyoming Valley of Pennsylvania, where Wayne County was located, had been settled primarily by people from Connecticut. The Morgans, for instance, had come from Groton, Connecticut, so I checked some vital records from Connecticut to see if I could find any Hoadley families that might have migrated to Pennsylvania. I also checked several Hoadley genealogies and found that there was a group that had come from Branford, Connecticut, and settled in the Wyoming Valley. In Branford’s vital records, I hoped to find a man named Hoadley who had married a Deborah. If I could find this, maybe I would have the right family.

Sure enough: A Ralph Hoadley married Deborah Frisbee on 5 May 1786—a possibility. To be “my” Deborah, Deborah Frisbee had to still have been of childbearing age after 1802, when she married George Morgan. Therefore, I looked for her birth record and found that she had been born in Branford on 8 July 1766, so she was just twenty when she married Ralph. Looking at more Hoadley vital record entries, I learned that Ralph Hoadley died 8 July 1796, leaving Deborah free to marry George Morgan in 1802. That became my hypothesis: Deborah Frisbee first married Ralph Hoadley, became Hoadley’s widow, then married George Morgan.

I continued my search. Deborah Hoadley, widow of Ralph, died 18 May 1807. Oops! Back to the drawing board. It was difficult for me to abandon a hypothesis that had looked so promising. When you think you already have the answer, it’s hard to keep looking for data that may disprove it, but it’s essential. Don’t get too attached to a particular individual—as I was to Deborah Frisbee—or too excited about tracing a particular name. I had really begun to hope that my Deborah was part of the family that invented the round things you throw in the park to your Labrador retriever, but it was not to be.

Honest blunders are not serious errors. Serious errors occur when facts are manipulated, squeezed, or somehow molded to fit a favorite, preconceived hypothesis—even when those facts contradict each other. The temptation to manipulate the truth often occurs with respect to identical names. So often we work diligently to gather enormous amounts of data on one family, only to learn that the person we’ve been pursuing was not our own ancestor but someone of the same name. It’s awful to have to admit that all the work we’ve accomplished thus far has been for naught, and that it will never fit into any of our pedigree lines. But if we refuse to do so, we will perpetrate serious errors.

John Tweedy was an early settler in St. Louis. Among his descendants was a grandson, Thomas D. Tweedy, who late in life joined the Grand Army of the Republic in Oregon. In his application papers, which his descendants kept, Thomas stated that his grandfather, John Tweedy, had fought in the War of 1812. According to the War of 1812 service records, a man named John Tweedy served in Illinois. A John “Twitty” was listed in the Union County, Illinois, 1820, state census. How many men of the right age could there be named John Tweedy? After the War of 1812, many soldiers simply crossed the river from Illinois into Missouri. I was tempted to stop my work there, assuming that I had found Thomas Tweedy’s grandfather, but I persisted.

Checking records in St. Louis County, Missouri, I found an 1829 deed in which John Tweedy had given a number of slaves to his children. He named those children as Joseph, Washington Walton, Adler, Calista, Mariah, Marshal, Watson, Robert, Elizabeth, Martha, John Alfred, and Landon.

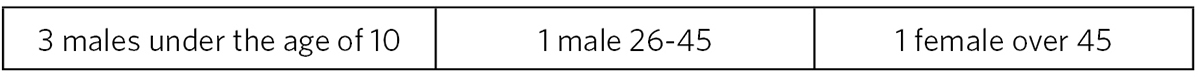

There was a problem. The John “Twitty” household listed in the 1820 Union County, Illinois, census consisted of:

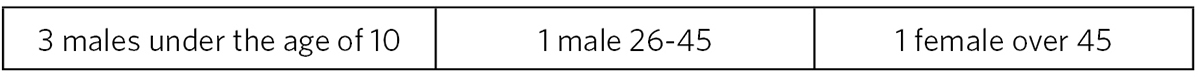

The John Tweedy household in 1830 in St. Louis consisted of:

The two households clearly didn’t match. When I tracked John Tweedy’s children to the 1850 census, two indicated they had been born in the early 1820s and gave their birthplace as Virginia. Could the John Tweedy who served in Illinois have returned to Virginia? Was there a John Tweedy listed in the 1820 census in Virginia?

This family fit much better with the family in Missouri in 1830. Campbell County, Virginia, documents such as tax records, deeds, and probate records indicated this was indeed the family who had moved to Missouri. John Tweedy had remained in Campbell County until about 1824, when he moved directly to Missouri. The man in Illinois shared his name, but he was not the same individual. Much of the work I had done on the John Tweedy in Illinois had to be discarded.

No one likes to abandon work already done. It’s so much easier and more enjoyable to continue pursuing avenues that seem to lead toward our destination—but if they’re the wrong avenues, we’ll inevitably have to turn around and go back. This brings us to the next mistake.

Beginning genealogists have to be warned that records frequently contain errors. Ages found in the census cannot always be believed. The birthplace listed for an individual in one census may conflict with the birthplace shown for the same individual in a later decade. Names are not always what they seem, either. The census taker may not have accurately spelled the name of the person for whom you are looking. Some people didn’t even spell their own names the same way all the time. (I’ve found instances where one name was spelled three ways on the same page.) Parents’ names on death certificates may not be correct. Beginning genealogists have to be warned that family traditions are not necessarily facts, and that actual documentation is required to corroborate information.

Having said that, it is dangerous to assume that the inconsistencies we find in old documents are simple errors that can safely be ignored. As I’ve worked in libraries and archives, I’ve noticed a disturbing trend. Many researchers who find information that conflicts with something they already believe tend to sweep away the inconsistencies with “good reasons”—or rather, with excuses and rationalizations. I hear people say, “The census taker must have missed him that year.”

Don’t be tempted to sweep away missing entries or conflicting data as so much trash. If census takers missed as many people as some researchers claim, we wouldn’t have much census material to work with. Considering the conditions under which counts were taken, the censuses are remarkably accurate. Although we know that they are incomplete, only a lazy genealogist would assume that “missing” data can never be found. Remember also that you must examine the actual census rather than just look in the index. If you can’t find a listing for the family you seek, check to see if other neighbors also were missed. Determine whether boundary changes or family migrations could account for the omission. Check for all phonetic variations in spelling. Otherwise, you’re neglecting necessary steps for finding the data you seek.

Ancestors who are missing from the expected tax rolls generate another excuse I often hear from some genealogists: “He must have been exempt from taxes that year.” The researcher is sure the individual was in the county being searched. He was married there; his wife has been identified there. Why is there no trace of him on the tax rolls? “He must have been exempt.” But was he?

Although Joseph Weaver’s family were all in Maury County, Tennessee—which is where all his descendants thought he was as well—I could not find him on any tax roll there between 1815 and 1830. Wouldn’t you like to know how to live in a county for fifteen years and never pay any taxes? Well, Joseph Weaver hadn’t figured it out either. He was simply not in Tennessee; he was living in Pike County, Georgia.

Another popular excuse may be given when a researcher identifies a man believed to be an ancestor, but then finds a dower release showing that he was married to a different wife than expected. The genealogist then decides, “The first wife must have died, and he remarried.” Don’t be too quick to “knock off” a wife. There are several other possible explanations. You may not have the correct man, but rather one with the same name; or the wife may have used a middle or nickname; or perhaps a divorce, not a death, occurred. One family assumed that when a wife married her second husband, her first husband, John Smathers, had died. The story had even progressed to the point where they believed that John had been killed in a hunting accident. Court records eventually revealed that the remarried woman had actually divorced John, who also had remarried and lived in Texas with his new wife and three children.

Consider the case of a will that doesn’t name someone firmly believed by all descendants to be the decedent’s child. The rationalizing researcher’s argument? “He must have been mad at her, so he cut her off without a dime.” Hannah Strain, supposedly the eldest daughter of Samuel Strain of Highland County, Ohio, married James P. Finley. According to a long-held family tradition, the reason that Hannah did not appear in Samuel Strain’s will (although he named his other twenty-one children) was that she was cut out by her staunch Presbyterian father because he disapproved of her marriage to a Methodist.

Onomastic (name-related) evidence and chronology seemed to support the belief that she was Samuel’s daughter. We know that fathers often omitted older children from wills if they had already received an advance on their inheritance. The problem in this case was that there was another man in the community, unrelated to Samuel Strain, who also could have been Hannah’s father. Thomas Strain had been ignored by genealogists because he was much more difficult to track, but further research showed that he was indeed Hannah’s father. She had not been named in Samuel Strain’s will because she wasn’t Samuel’s child. Researchers had formed an excuse and kept her in the wrong family for nearly a hundred years.

When records conflict, creating a “good reason” for the discrepancy is easier than reviewing the inconsistencies and digging into the records for more details that might reveal the truth. It’s also hard to admit that the theory you’ve believed for years might be wrong. If you keep an open mind and continue to evaluate those conflicting records, you can probably resolve the incongruity in some other logical way.

When the idea is phrased this way, most people would agree that it sounds ridiculous. One of the first rules of genealogical research is to always move from the known to the unknown; yet many researchers violate that rule. They try to link themselves to a famous historical figure; to an accepted, proven pedigree; to a published genealogy; or to a person from an earlier time period who had the same name and was living in the same community where they think their ancestor should have been. These are particularly tempting methods for researchers who do not have easy access to records in the area where their family lived. People who take the easy way, however, usually have as much success as the drunk who looked for his lost coin under the lamppost where the light was better, instead of in the dark street where he dropped it.

How many times have you heard a genealogist say something like this: “Our ancestors came from England to Braintree, Massachusetts, about 1650. The only thing I have to do now is link them to my family in Hamilton County, Ohio, in 1833”? Or, how many of you have found a man of the same name as your ancestor—say, a fairly unusual name like Miles Cary—living in a location where you think your ancestor once resided, and then you tried to link them together even though one was recorded there in 1776 and the other in 1830. Haven’t you done that? Be honest. I certainly have!

Records do not exist in a vacuum; they belong to a set of events and documents that need to be examined.

When I began my research, I found that Abraham Newcomer was a very unusual name in Warrensburg, Johnson County, Missouri. I tracked him back to 1850 in Cumberland County, Pennsylvania, without much difficulty. The family Bible said that Abraham Newcomer had married Mary Musselman in 1812 Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. There was an Abram Newcomer listed in Lancaster County in the 1810 census. Do you think that I ignored that and continued to work in Cumberland County, studying the Abraham Newcomer that I knew to be the right man, getting to know him by reconstructing his family and his associates? No way. I wanted to move backwards. I wanted to find the immigrant! So I immediately jumped to Lancaster County and started copying records that contained men named Newcomer. It seemed, however, that there were people named Newcomer by the thousands. There were at least five Abraham Newcomers living in Pennsylvania between 1750 and 1800—not to mention eighteen Newcomers named John and fourteen named Christian. After searching for twenty years, I still have not identified the father of Abraham Newcomer of Cumberland County, Pennsylvania.

Nothing will waste your time more than forgetting the crucial lesson of moving from the known to the unknown. For every success you have linking one name to another by working both ends of the chain, you will probably have ten failures.

Too often, we study documents as if they had no relationship to the people who created them. Don’t put your documents in boxes—connect them, correlate them, look at other records that were produced at the same time, and analyze them in context. These records were produced by real people for specific reasons. Think about what those reasons were. Are they consistent with other things that your ancestor did? For instance, would a man who was shown on the tax roll as owning one cow and no other property in 1815 write a will the following year in which he bequeathed three horses, four cows, and 160 acres of real property? Compare documents and correlate the information.

The following case is an effort to identify and distinguish four men named John Franklin, all of whom lived in south-central Kentucky around 1800. The following tax listings come from a microfilmed copy of the Barren County, Kentucky, tax rolls, available through the Kentucky Historical Society. In 1807, John Franklin, Sr. paid taxes on 150 acres on Beaver Creek, where he had lived since 1799.

John Franklin, 150 acres 2nd rate land, Bvr Creek entered by Scot, 1 poll, 3 blacks over 16, 6 blacks under 16, five horses.

In 1808 there were three men named John Franklin on the tax roll, but no John Franklin, Sr.:

John Franklin, 170 acres of 3rd rate land on Barren’s Creek entered by I. Lowe. 1 poll, 3 blacks over 16, 17 blacks under 16.

John Franklin Jr. 100 acres of 3rd rate land on Barren’s Creek entered by Thos. Bandy, 1 poll, 1 black under 16, 6 horses.

John Franklin 100 acres of 3rd rate land on B.S. Crk entered by Goodwin; no polls, no horses, no blacks.

What had happened to him? None of the above named men were designated by Sr., although one man was using the designation of Jr. Who, if any, of those listed on the tax roll was the man for whom I was searching?

Perhaps John Franklin, Sr. had died. If so, there should be probate records for a man with that much real and personal property, but I could find no probate and no sale for the 150 acres on Beaver Creek. Maybe John Franklin, Sr. was the man who didn’t pay a poll because he was overage. If that were the case, why did he sell all of his personal and real property?

He could have moved away, but he didn’t. I could find no record that John Franklin sold the land on Beaver Creek, nor that he bought the land on Barren’s Creek. The man living on Barren’s Creek had almost the same personal property as the man who lived on Beaver Creek—which tells us that we should keep looking at the records in this community. How can we determine how John Franklin acquired that land if we can’t find a sale? Is there anything else on this tax roll that might give us a clue where to look next? A man by the name of I. Lowe entered that piece of property on Barren’s Creek. Isaac Lowe left a will. In it, he said:

It is my will that my executors raise the money to pay the State price of the tract of land I exchanged to John Franklin, Senr. and to get a grant and have a conveyance made to the said Franklin when a patent is issued.

By correlating two clues from the tax roll with one from what appeared to be an unrelated record, we have solved the problem. John Franklin, Sr. was still in Barren County, now living on Barren’s Creek.

Don’t confine your research by studying only one document at a time. If you do, you won’t be able to reconcile conflicting data.

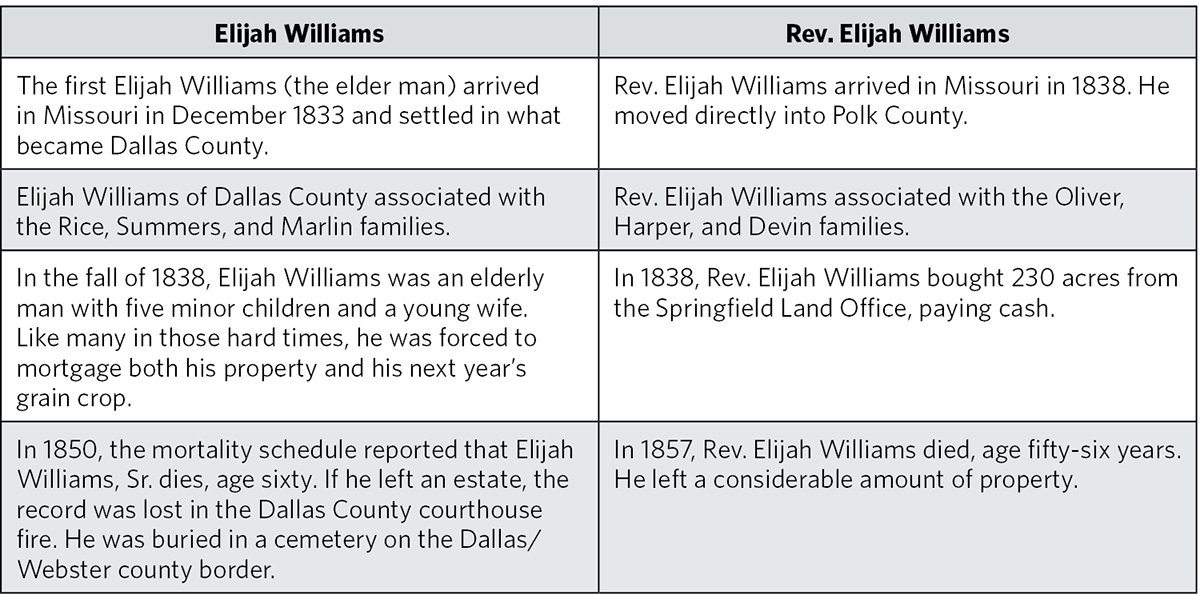

Some researchers believed that Rev. Elijah Williams of Polk County, Missouri, was the son of another Elijah Williams who lived in adjoining Dallas County. However, the records that the two men generated during their lifetimes point away from such a connection, rather than toward it.

Even if the chronology didn’t prove that the two men couldn’t be father and son, their behavior did. I don’t think most sons—particularly one who was a Christian minister—would callously ignore the economic troubles of their father and half-siblings. Although their names would suggest a relationship, their recorded behavior does not.

Genealogists love to tell about all the wonderful cases we have solved, and all the marvelous discoveries made possible by our brilliant research. If you listen to too many genealogy experts, you may begin to believe that we have these little magical document boxes. If we ever encounter a problem that we cannot solve, we simply leave the magic boxes at the archives, and they fill themselves with long-lost, detailed documents while we sleep.

Some families are able to locate magically detailed documents, such as land partitions that name all the heirs, or wills that identify specific relationships. For other families, however, such documents don’t seem to exist. I have heard a genealogist say, “I have researched this family for years, and I just know Absalom’s father is Meshach, but I can’t find the proof.” That tells me that she probably is searching for a magic document. If indeed she has studied Absalom for years, reading every document that he produced—if she has studied his children, siblings, nephews, and nieces, and all the records they produced, and if she then thoroughly investigated Meshach, studying all the documents that he and his associates produced—this genealogist should be able to put together a beautiful argument for her case. She could produce circumstantial evidence for the relationship, and show how the two men fit together. Even if those records do not provide “proof,” they will show whether or not the two men were linked during their lives.

I fear, however, that most genealogists merely skim all those records produced by Absalom, his children, brothers, and sisters, then they skim the records produced by Meshach, looking only for that magical phrase, “my son.” When they don’t find it, they give up because they lack “proof.”

The most effective strategy is not to keep looking for a magic document, but to gather as much information as possible. Carefully examine each record you find, correlate the data with that in other records, and look for circumstantial evidence that will establish relationships among them. For an example of this type of search, see my “Problematic Parents and Potential Offspring: The Example of Nathan Brown,” published in the June 1991 issue of the National Genealogical Society Quarterly. This article, which describes my fruitless search for records that would conclusively prove a connection between the immigrant Nathan Brown and his children, will give you an idea of how to proceed in similar circumstances. I never found the magic document. But the case is so strong that no one but Nathan could possibly have been the father of those children.

Because the census is so readily available, it is easy to make the mistake of just going from one decade to the next, searching for one nuclear family. When that family cannot be located in the expected census or index, or there are too many people of the same name to be able to distinguish them, the researcher hits a brick wall.

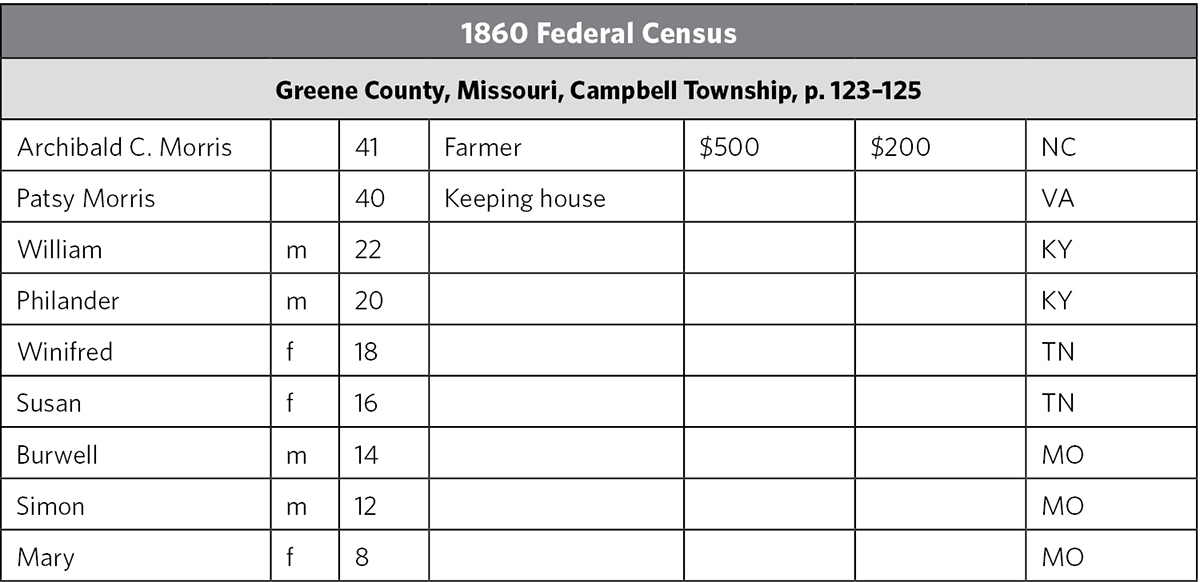

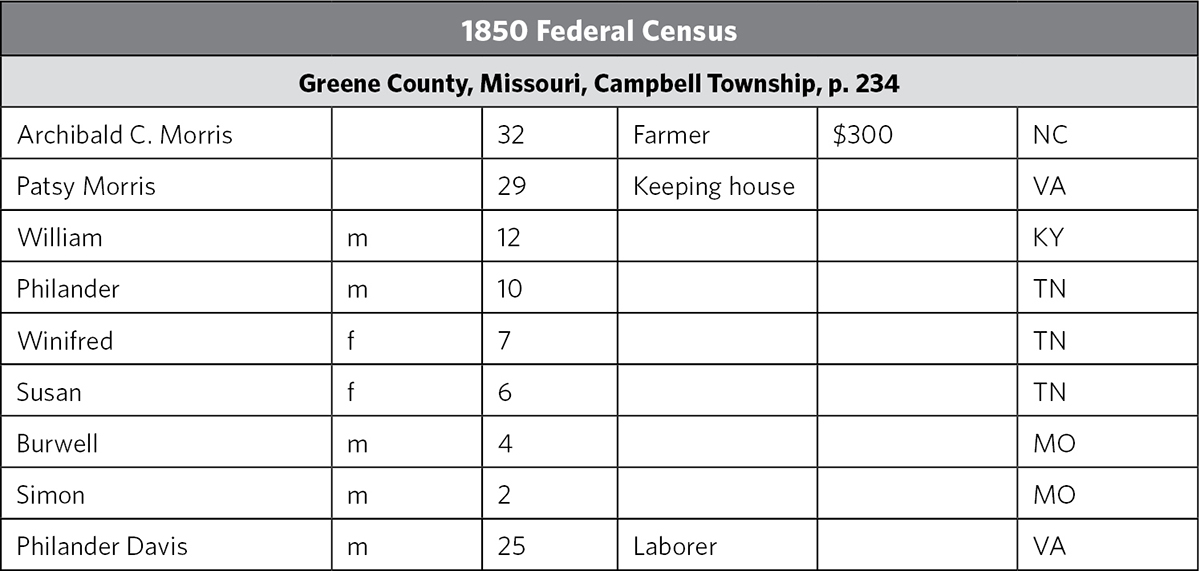

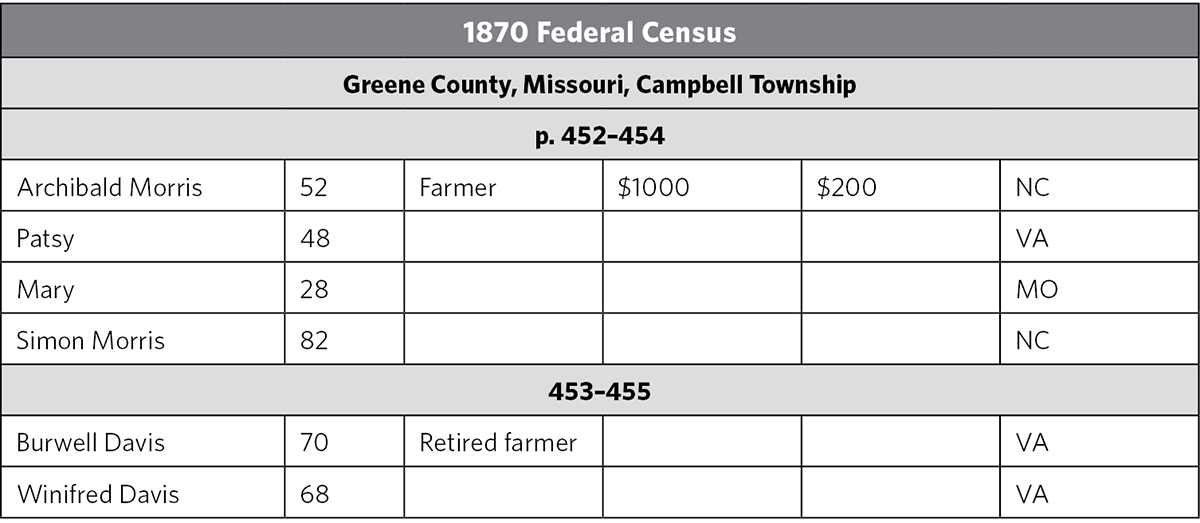

The following chart is a typical census record for a family living in Greene County, Missouri. We’ll use it to help us find Archibald C. Morris’s parents, and his place of residence before he moved to Missouri.

Because we can deduce from the ages of the children that the family must have been in Missouri at least since 1850, the next step is to check the 1850 Missouri census to verify their county of residence and perhaps obtain more helpful information:

Notice that the family in the 1850 census includes two people with rather unusual names. Archibald had a son named Philander, and now we find another household member who also is named Philander. Even though the census says that he was just a laborer or a hired hand, we know it’s important to note those individuals as well. A name as unique as Philander is a revealing hint towards a relationship, but it pays to look into every individual in your household of interest.

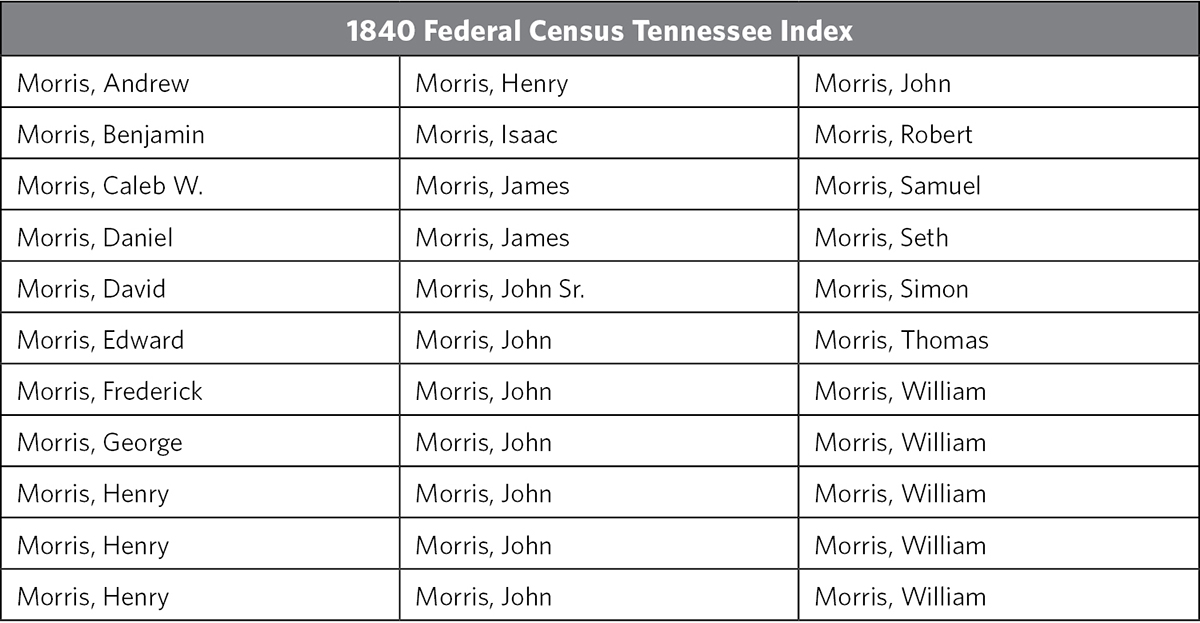

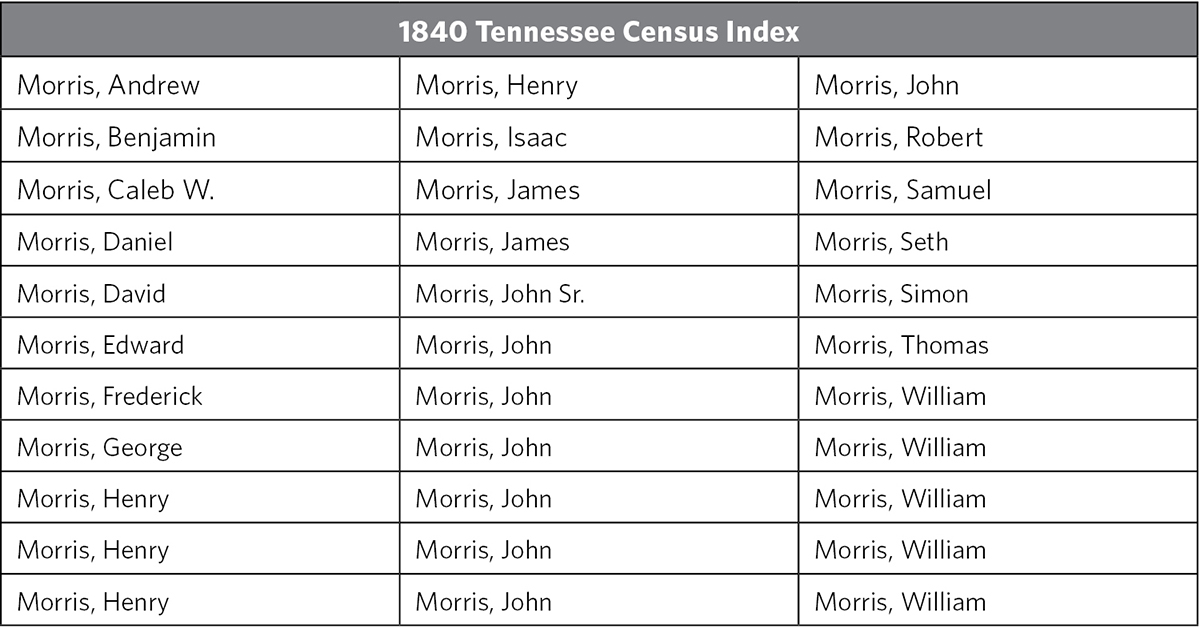

Again, data from the two censuses tell us that the family was apparently in Tennessee in 1840, so we check the census index:

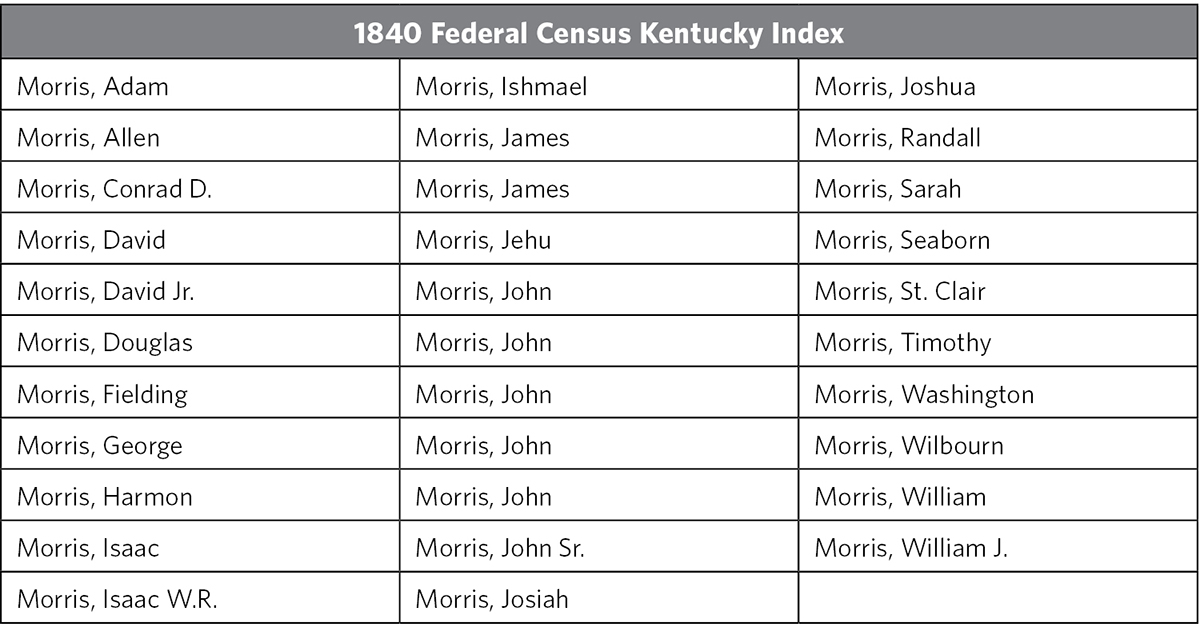

No Archibald Morris. Maybe the census taker in Missouri made a mistake when he wrote down the ages of the children, or perhaps he was given incorrect information and the family was actually in Kentucky by 1840.

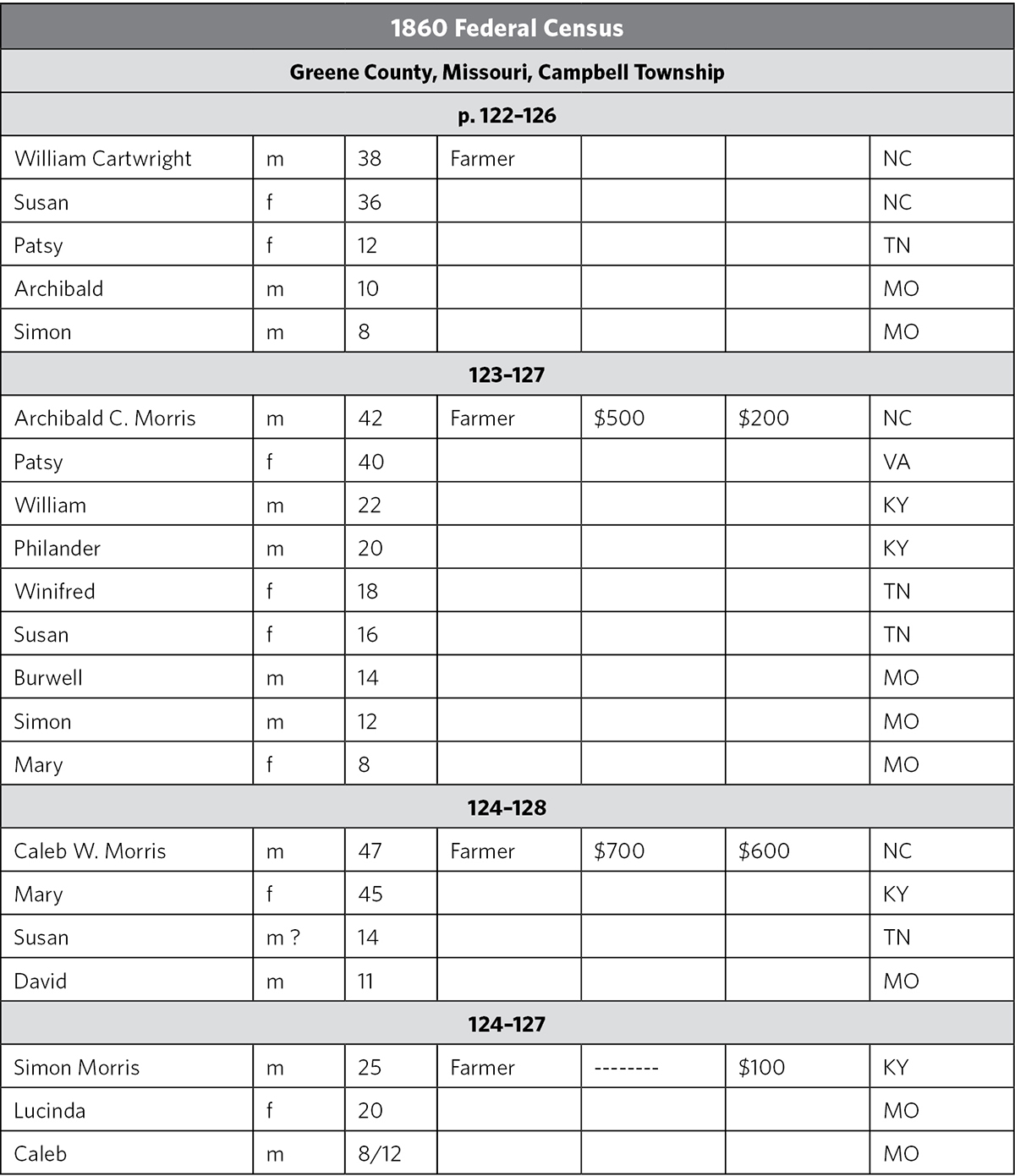

There were plenty of Morris families living in Kentucky too—but no Archibald. Leaping across the decades has brought us to a dead end, so we had better go back to the censuses of Greene County and this time not just concentrate on the nuclear family. Let’s also look at the neighbors listed in that census and see if they can give us more information about Archibald. Archibald is a rather unusual name, so let’s see if there were any others by that name in the neighborhood:

The family listed above Archibald Morris had a child named Archibald, one named Patsy, and one named Simon. The ages and birthplaces given for the children living in that household follow a pattern similar to that of the Morris family. That should help us. Listed on the other side of Archibald Morris’s household was a man named Caleb Morris. His age was given as forty-seven, so he was obviously not Archibald’s father, but he could be a brother.

Do you notice anything else from his listing that might give you any further clues? How about the naming patterns? Simon Morris was listed next to Caleb. Apparently, Simon lived with Caleb because he was not listed in a separate dwelling, even though he had a separate household. As a farmer, Caleb Morris owned real property. We can see from the second number after Simon’s name that, although he had personal property, he owned no real property. Simon was probably just starting out, so there is a good possibility that Simon was Caleb’s son.

Have we overlooked anything in our census work? Shouldn’t we look for Archibald Morris in North Carolina, where he was born? The answer is no. Moving census research to an individual’s state of origin before later censuses listing him as head of household have been fully explored is a common mistake. If we couldn’t find Archibald Morris in Tennessee or Kentucky, the last places he was thought to have lived before moving to Missouri, how could we hope to find him way back in North Carolina? Certainly no birth certificates for that time period are available there. Even if we did find an Archibald Morris in North Carolina, it is unlikely to be our man from Missouri because the gap between the two time periods is too wide to establish a definite connection.

In this particular search, we have gone from the 1860 census to the 1850 and then to the 1840, and (although we’ve learned a little more from checking some of the neighboring households) we’re stuck. Instead of continuing to move backward in time, let’s go forward and see what we might learn from a later census. I have heard so many genealogists protest, “But I know all about the family at that time period already.” You’d be surprised what later censuses can reveal.

By the 1870 census, there was an older man living with Archibald, probably his father. Simon was born in North Carolina, as was Archibald. This new household member may have generated some records of his own. This is what we are looking for: new people coming and going.

Caleb Morris no longer appears in the immediate vicinity, so he probably moved some distance away—although he still could be in the same county. Archibald’s neighbor in the 1870 census was Burwell Davis. We can’t ignore him; remember that Archibald had a son named Burwell. Also remember that another Davis—Philander—was living with Archibald in 1860. We now have several possible avenues for further research: Simon Morris (possibly Archibald’s father), Caleb Morris (possibly Archibald’s older brother), Burwell Davis, and Philander Davis (both possible relatives). And of course, we are dying to get back in North Carolina, aren’t we? Before we proceed there, however, we still need to discover where the family was in 1840, so let’s go to the censuses for Tennessee and Kentucky:

Simon and Caleb Morris were listed in the 1840 census index and were in the same county. Archibald apparently was too young to be listed as a head of household. Now that we have a possible county of residence in which to search, we can focus our study to see if we can find corroborating records that indicate our Archibald Morris belongs in this family. As you can see, it is important to build a web of family relationships in the area where you can confirm individual identities, so that when you are ready to follow the trail into a new state, you have more people to look for. This example was a simple one, but the method also works for more complex problems if you examine enough records.

Remember that the best clues to origin lie in the community where your ancestor’s place of residence already has been established, not in the county where you think he might have been earlier.

Welcome all name gatherers! The contest is about to begin. How many records of people of the same surname can you find? Compete with your friends. Fill file drawers, stuff cabinets, and load databases. Cover the dining room table, cram closets, and shove records under the bed. Don’t prejudice your search by looking only where your ancestor lived; look everywhere! Gather names from all over the country.

Seriously, no one would recommend that you stop looking for a particular surname—just don’t confine your search only to people who bear that surname. To be a successful researcher, you must also seek and study the people who associated with your family. Broaden your horizons. When you hear of someone else who is researching a surname of your interest, learn what time period and geographical location they are working with so that you can determine whether or not that family might be connected with yours.

Some people (for example, Christine Rose, CG, CGL, FASG) focus on collecting information on particular surnames to disperse among a large group of people. That’s fine. But if your goal is to find a link with one ancestral family, you probably will be more successful if you consider their migration pattern, their neighbors and associates, and the people who lived with, depended upon, and cared for your ancestor, even though those individuals may not have the same surname. Otherwise, you are going to collect drawers full of information that you will never use, and study a lot of people who are not even remotely connected to you.

Just because a record is old, you cannot assume that it is contemporary with your ancestor. A document describing your ancestor may be 150 years old, but if it was created sixty years after your ancestor died, how sure can you be that the information is accurate? If your children were to write today about something that you said or did sixty years ago, would they get it right? Three examples of old records that frequently contain questionable information are death certificates, stories, and family Bibles.

Death certificates are primary sources that provide direct evidence for two pieces of information about a death: date and location—but not cause. You cannot depend on a doctor from the nineteenth or early twentieth century to accurately determine what caused a death. I have also seen examples where a doctor fudged information when reporting a suicide or a stigmatized disease in order to protect family members. Moreover, the primary cause of death is not necessarily the underlying cause. One doctor wrote on a death certificate that the primary cause of the man’s death was a blow to the head. The secondary cause was another man’s wife.

Other than the date and place of death, all information on a death certificate must be considered as hearsay. The decedent obviously could not have been the person who wrote the certificate, and the recorder may not have been the one who supplied the information or entered it on the original form. Someone could have made a mistake in spelling or interpretation. We often forget that individuals completing death certificates were likely to be under great emotional strain, and that stress might distort the accuracy of the information they supply. To someone who has just lost a loved one, it may not seem important to remember the deceased person’s mother’s maiden name.

Traditional family stories have their place and can provide good clues to follow up with research, but they often perpetuate erroneous information. Watch for these common mistakes:

Likewise, Bibles are an important source of family records, but unless the events were recorded as soon as they happened, these documents also may be subject to errors and distortions. Bible records may have been copied from an older Bible, or they may have been reconstructed in a new volume from memory. Consult the December 2002 issue of the National Genealogical Society Quarterly for an in-depth discussion of Bible records.

Study up on ways to keep your research organized with Drew Smith’s book Organize Your Genealogy (Family Tree Books, 2016) <www.familytreemagazine.com/store/organize-your-genealogy-paperback>.

More and more people are discovering the joy of finding their ancestors. More people are attending genealogical conferences, taking classes, and engaging in research. With so many now working in the field of family history, we have the potential to discover more connections and link more families than ever before. But are we sharing the information we have? Or are we so busily engaged in our own exciting searches that we never take time to assemble, organize, and publish our discoveries so that others can benefit? What would happen to our research if something happened to us?

If, for some reason, you couldn’t return to your office, would someone else be able to walk into it and know what material should be saved, what should be published, and what should be donated to a society? Will someone else take the time to organize your research if you don’t? It isn’t necessary to publish a book. Many genealogists have neither the interest nor the money for such an undertaking, but there are other ways to make the fruits of your hard work available to other researchers.

To begin, keep your files, documents, family notebooks, and photographs carefully arranged. Remember that if you’re reluctant to begin organizing your own computer files and the stacks of papers and notecards you’ve accumulated, no one else will want to do it either. Analyzing, arranging, and typing the material is as much a part of the research process as the actual investigations themselves. Your research is not done until you have properly organized it.

Once your research in a particular area is complete, donate photocopies of your work to your state historical society, or to historical or genealogical societies in the community where your ancestor lived. Submit articles to local, regional, and national genealogical journals so that other people can learn of your successes—and possibly help you further your own research. Please don’t let your contributions be lost. That would be the biggest mistake of all.