Whence, I often asked myself, did this principle of life proceed?

— Victor Frankenstein, Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus, 1818 1st Edition

Anonymous 1

Frankenstein: The name is synonymous with a slow-moving, half-witted, oversized monster that was created from a dead man’s body and bestowed with a murderer’s brain by an obsessed scientist. Hollywood has so framed the creature’s identity in the public image that few today are aware that it was the creator and not the creature who is actually Frankenstein. Fewer still would raise an eyebrow that the scientist’s name in the 1931 Universal horror movie was Henry Frankenstein, whereas the main character in the novel was in fact Victor Frankenstein. One wonders how many are aware that the combined parts for the framing and creation of the so-called fiend were both human and animal in this early transhumanistic experiment of Frankenstein.2 It is curious that the public perception and confusion of identity regarding “Frankenstein” is a mirror image of the confusion over authorship that was embedded into the novel from the day of its initial publication in 1818. How few today are aware that Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus was first published anonymously? Fewer still are aware that the first critics ascribed credit to Percy Shelley rather than Mary Shelley as the author of the 1818 novel. Is it accidental, coincidental, or intentional that one of the most widely read novels in the English language is shrouded beneath a veil of confusion? It is the argument of this book that the facts demonstrate intention rather than coincidence, and misdirection rather than confusion. Frankenstein is a biography of Percy Shelley, or perhaps is better described as a fictionalized autobiography by the young Romantic poet who died in 1822, shortly before his thirtieth birthday.

Evidence within the novel suggests certain driving influences were at work upon the author of Frankenstein. Chief among the obvious influences revealed in the novel are Shelley’s devoted study of science and alchemy. Other notable influences at work in the author that are discernable in Frankenstein are androgyny, atheism, and anti-government secret societies or fraternities—particularly the Bavarian Illuminati. Additionally, one cannot help recognizing the author’s focused attention in developing characters whose traits revolve around their conflicting need for a soul mate while their actions undermine the possibility of a lasting relationship with their soul mate. The pilgrimage after Platonic love is frustrated by every male character and leads each of them to face the consequence: loss, rejection, abandonment, and isolation. There is a consistent psychological component running throughout the novel and one must ask how much of it is found in the inner conflicts of the author. Furthermore, Frankenstein is set against a backdrop of radical independence: first, a sailor embarking to an “uninhabited land,” a paradise, holding answers to scientific mysteries; secondly, an alchemist-scientist determined to discover the principle of life while opposed by his contemporaries; and third, a creature whose superhuman abilities and indescribable nature are part of the sublime fabric woven into the story’s backdrop.

Moreover, much might be argued from what is not evident in the novel, i.e., intimate relationships between men and women, strong female characters, and the role of God. There is a glaring lack of fate or divine providence at work in the story of Frankenstein. Female characters in this novel are virtually unsubstantial shadows and passing vapors set against a rugged and sublime masculine environment in Frankenstein. In a curious fashion, this is a manly book to be sure, a novel—from start to finish—which unfolds from a uniquely masculine point of view, and note that the masculinity is distinctly such as the masculinity of Percy Shelley: unique! Frankenstein is not merely a middle-of-the-road masculine-leaning story, it is a specific kind of manliness that fills the pages, a distinctive androgynous, antisocial and independent sort of masculinity. It is not difficult to form an opinion about the person writing the story or identify the author’s characteristic fingerprints in Frankenstein.

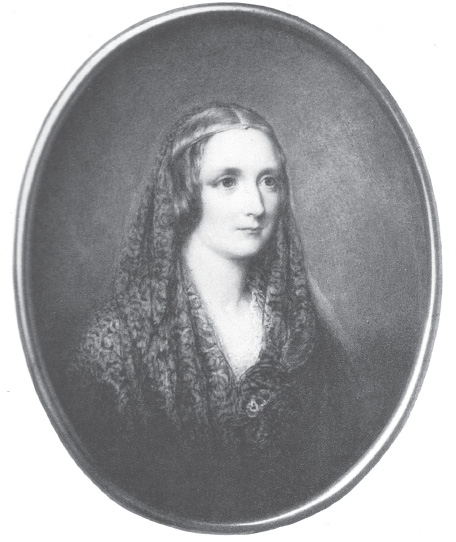

It should not come as any surprise that it was initially thought highly unlikely, if not impossible, that an eighteen-year-old girl was behind a story with such themes! Even modern feminist studies have had to wrestle with these problems, if not forced to preempt the internal inconsistencies of Mary Shelley as the author with their own creative solutions. Yet, today even the once anonymously written 1818 edition of Frankenstein bears the name of Mary Shelley as its author. Case closed.

There is no shortage of studies that can be found to support and analyze the authorship of Frankenstein by Mary Shelley. The argument for Mary Shelley as its author is relatively a non-argument in academic circles, and to raise a question concerning Mary Shelley as the author is to risk being labeled as a woman-hating troglodyte. What more needs to be said to end the brief and bewildering conversation concerning Frankenstein’s author than the very admission of Percy Shelley himself, that it was Mary and not he who wrote the novel? Why raise the question at all? By the time Frankenstein was released in its more popularly revised edition (1831), almost a decade after the death of Percy Shelley in 1822, the novel was no longer being published anonymously; it was printed with Mary Shelley’s name as the author. As if to clear up any remaining confusion, Mary wrote an altogether new Preface for the book and gave a detailed account of how the book came to be written by her.

The question of authorship would seem to have been finally settled beyond any reasonable doubt, and yet, much like the name “Frankenstein,” there still remain many confusing facts and inconsistencies in attributing the story to Mary Shelley. This book will argue that a case can be made that a serious misidentification has taken place regarding the author and demands a closer look. For that closer look we must begin with the anonymously written Preface to the 1818 edition and afterwards make a careful comparison to the Preface written in 1831.

THE PROBLEM WITH THE PREFACES 1818 PREFACE

A discerning and unprejudiced examination into the Frankenstein Prefaces will raise more than a few challenging questions, reveal several nagging inconsistencies, and cast serious doubts regarding Mary Shelley’s authorship of Frankenstein. The Prefaces are as personal as fingerprints revealing the author’s personality, his or her influences, education, and experiences. The Prefaces connect the author’s life to the story, therefore one must expect that if a single author penned the 1818 edition and then revised his or her work a decade later, very little would change; the details would remain consistent. Yet it is precisely here in the section with the most personal evidence that the first red flags are raised for the careful reader. Consider first, the Preface to the 1818 Edition, the very edition which was published anonymously:

The event on which this fiction is founded has been supposed, by Dr. Darwin, and some of the physiological writers of Germany, as not of impossible occurrence. I shall not be supposed as according the remotest degree of serious faith to such an imagination; yet, in assuming it as the basis of a work of fancy, I have not considered myself as merely weaving a series of supernatural terrors. The event on which the interest of the story depends is exempt from the disadvantages of a mere tale of spectres or enchantment. It was recommended by the novelty of the situations which it develops; and, however impossible as a physical fact, affords a point of view to the imagination for the delineating of human passions more comprehensive and commanding than any which the ordinary relations of existing events can yield. 3

The first paragraph of the Preface reveals an author who has far more than a passing familiarity with science; indeed the author is clearly endowed with an educated mind and inquisitive spirit that is dedicated to contemplating the deeper questions of science and human nature. The Preface reveals an author who has researched and been trained in rather advanced and esoteric material. He or she, according to the Preface, has been schooled in the writings and radical ideas of Erasmus Darwin (grandfather of the renowned scientist Charles Darwin) as well as the German physiologists.

Darwin’s writings, including The Botanic Garden (1792), Zoonomia (1796), and in particular The Temple of Nature (1803), were profoundly inspirational to one person closely connected to Frankenstein, namely Percy Shelley—as early as 1811, at least seven years prior to the publication of Frankenstein.4 Richard Holmes, in his biography Shelley: The Pursuit, writes that Darwin was “one of the archetypes of [Percy] Shelley’s much admired eccentric scholars” and “Darwin’s fusion of Science, philosophy, and poetry, was to prove an inspiration to Shelley.”5 It is unquestionable that the emotions of human sympathy and loneliness expressed in Darwin’s poetry were carried over into the traits associated with Frankenstein’s creature—as well as experienced by Percy Shelley. Consider Darwin’s Canto IV in the Temple of Nature:

AND now, e’en I, whose verse reluctant sings

The changeful state of sublunary things,

Bend o’er Mortality with silent sighs,

And wipe the secret tear-drops from my eyes,

Hear through the night one universal groan,

And mourn unseen for evils not my own,

With restless limbs and throbbing heart complain,

Stretch’d on the rack of sentimental pain!5

— Ah where can Sympathy reflecting find

One bright idea to console the mind?

One ray of light in this terrene abode

To prove to Man the Goodness of his GOD?6

The words of Darwin are reminiscent of a man struggling to find a place in the world, sympathy with others, understanding, justice, meaning, and questioning the existence of God. The poetic themes found in Darwin are mirrored in the entire canon of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s writings.

What of the German physiologists, whose influence, along with Darwin, were to be the threading that created the fabric from which Frankenstein was woven into a story? Few German physiologists are more notable than Albertus Magnus, the thirteenth-century Franciscan bishop, Doctor of the Catholic Church, and highly regarded philosopher. Albertus Magnus holds the rare distinction of claiming to have discovered the Philosopher’s Stone, the elixir of life. This same Albertus Magnus, tradition claims, was a magician, alchemist, and the creator of an artificial human, a homunculus. The very same Albertus Magnus is explicitly mentioned in Frankenstein as one of three men to have been the early influence behind Victor Frankenstein’s obsession to assemble a creature from dead parts and then animate it with new life—in short, to create another type of homunculus. The key question is, what relationship, if any, exists between Albertus Magnus and Percy Shelley?

Newman Ivey White’s monumental two-volume biography of Percy Bysshe Shelley reveals that between 1804 and 1809, while Shelley was still an adolescent studying at Eton,

Shelley’s scientific interests simply continued the enthusiasm for the mysteries and possibilities of Natural Science … ranging from the physical to the metaphysical, he absorbed the scientific reveries of Albertus Magnus and Paracelsus with eager enthusiasm for new sensation.7

Observe that the author of the original 1818 Preface is not simply weaving a series of “supernatural terrors” nor telling another “mere tale of spectres or enchantment,” but explicitly stating scientific potentials. The author is proposing, through the literary genre of fiction, scientific ideas which were born of personal study, ideas which were the currency of modern advances in science. The author used a personal awareness of possibilities in science as the dock from which to embark into a philosophical sea of human uncertainties. The story has a supernatural element to it, perhaps even the feel of imitating ghost stories from times past, but the author of the 1818 edition Preface wants the reader to be forewarned that this story is different! Frankenstein has a basis in potential; it is a scientific possibility, and therefore it is fiction embedded with a reasonable element of wonder because of the frightening potentials. In reality, this is science fiction, though the genre had not yet been attributed to any work of fiction at this time. Frankenstein is science fiction because the author was a person of science, dare we say a “man of science,” who was well acquainted with scientific advances and with the “men of science” of that time. This fact alone about the author should raise an eyebrow.

Carl Grabo, author, professor, scholar, and a foremost Percy Bysshe Shelley authority, analyzed the writings of Shelley from the standpoint of how science influenced his poetry and prose. Grabo identified science as a key imprinted theme within Shelley’s poetry. While Grabo conducted research for a book that he was writing as an analysis on the meaning of Shelley’s profoundly difficult epic poem Prometheus Unbound, Grabo also determined that he would have to write another book solely dedicated to the subject of Shelley and the role of science. The second book was titled A Newton Among Poets.8 In that book, Grabo states, “under slightly altered circumstances Shelley would have become a scientist”9 and “the weight of evidence is too great, the consistency of Shelley’s employment of scientific fact and theory too notable, to be denied.”10 For biographers of Percy Shelley this would come as little surprise; it was the study of science that took the greatest hold of young Percy Shelley when sent off as a child to Syon House and later to Eton.

In James Bieri’s comprehensive biography Percy Bysshe Shelley, he describes how even in his childhood the influence of science began to form a foundation for Shelley’s philosophy and writing:

The lectures at Syon House on science and astronomy by the itinerant Dr. Adam Walker left an indelible imprint on Shelley. Walker, a science enthusiast and inventor, gave a series of vivid talks and demonstrations covering many scientific topics, as indicated by the title of his eighty-six-page pamphlet “Philosophy, viz. Magnetism, Mechanics, Chemistry, Pneumatics, Fortification, Optics, Use of Globes, etc., Astronomy.” Fascinated with these lectures, Shelley probably heard them again at Eton, another of Walker’s stops. Shelley’s lifelong interest in chemistry, electricity, optics, and particularly astronomy infused his poetic imagery. Before leaving Syon House, when he was about twelve, Shelley began “scientific” experiments on his sisters and others at Field Place.11

Helen, Shelley’s sister, describes the youthful Shelley as a Frankenstein in the making, an eccentric alchemist/scientist at the ripe age of twelve:

When my brother commenced his studies in chemistry, and practiced electricity upon us, I confess my pleasure in it was entirely negatived by terror at its effects. Whenever he came to me with his piece of folded brown packing paper under his arm, and a bit of wire and a bottle … my heart would sink with fear at his approach.12

Newman Ivey White adds to the picture of Percy Shelley’s adolescent fascination with scientific experiments:

He sent up fire-balloons, as other Eton boys were doing also. One Etonian represents Shelley’s interest in explosives as extending to the purchase at auction of a brass cannon, which was captured by the tutors before it went into action… Shelley experimented with chemical brews and nearly blew himself up; he poisoned himself once. In confederation with Edward Leslie, he electrified a tom-cat. Striking higher, he even electrified “Butch” Bethell when that blundering tutor and landlord too hastily investigated a galvanic battery. At Field Place during vacations he was also demonstrating certain effects of powders and acids to his young sisters. He bought small electrical machines that were vended among the students by Adam Walker’s assistant and with the aid of a traveling tinker he constructed a steam engine that duly exploded.13

Critically important in understanding the relationship of a scientific background necessary for the writing of Frankenstein and how it had a direct connection to the young Percy Shelley is the role of Doctor James Lind, Shelley’s tutor at Eton. James Bieri describes Dr. Lind as a “latter-day Paracelsus” with an “apparatus-filled study” which “embodied Shelley’s childhood fantasies…”14 The Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine (May 2002) dedicated an article to the role of Dr. Lind, his influence in advances made in eighteenth-century science, and how these factors relate to the author of Frankenstein:

…doubts exist concerning Mary Shelley’s degree of specific interest in, or knowledge of, scientific subjects. Accordingly, the level of influence exerted in this field by her husband, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, also remains open to debate. He maintained a keen interest in the world of natural philosophy, and many critics have noted the significance of the references to ‘Dr. (Erasmus) Darwin and some of the physiological writers of Germany’ in the novel’s Preface… a closer examination of the medical themes running throughout the novel strongly suggests a more obscure influence at work, arising from Percy Shelley’s friendship with a Scots doctor whilst he was still a schoolboy at Eton.

During his last two years at Eton in 1809–1810, Percy Shelley became the friend of an elderly gentleman who was one of a number of persons approved by the school as suitable mentors for the boys.15

Astonishingly, Christopher Goulding, the article’s author, has placed his finger on the very issue that not only reveals the writer of the Preface but also manages to pull back the veil and reveal whose knowledge and influence was at work in writing Frankenstein. In a bewildering fashion, however, Goulding maintains the role of Mary Shelley as the author of Frankenstein, a book dependent on a high degree of exposure and education in experimental science, which she did not have. Undoubtedly, it does require a tremendous effort to ignore the obvious—namely, the author of the novel is most likely to be the person who is already qualified in education and life experience: Percy Shelley.

Goulding continues,

Certain medical themes and quasi-autobiographical events in Frankenstein suggest the influence of Lind’s character and work, via his pupil Percy Shelley. The description in the novel of Victor Frankenstein’s medical studies at the University of Ingolstadt is an idealised version of Percy Shelley’s scientific education, with the character Waldman, the chemistry lecturer, owing much to Lind. And an examination of Lind’s own experiments reveals that he was even closer to the world of Frankenstein than has hitherto been acknowledged. Between 1782 and 1809, Lind maintained a regular correspondence with the London-based Italian physicist Tiberio Cavallo. Cavallo mentions Galvani’s experiments on 19 June 1792, the year following publication of Galvani’s research. On 11 July he asks Lind, ‘Have you made any dead frogs jump like living ones?’ And then on 15 August he writes, ‘I am glad to hear of your success in the new experiments on muscular motion, and earnestly entreat you to prosecute them to the ne plus ultra of possible means.’16

With astonishing objectivity, The Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine supplies the obvious yet too often overlooked factual evidence that virtually guarantees the case for Percy’s key role as the author of Frankenstein, via his education and life experience with Dr. Lind while at Eton:

Running alongside Frankenstein’s central plot concerning the creation of a monster, parallel themes address contemporary perceptions of the increasingly blurred boundary between life and death. These include an early excerpt where Victor Frankenstein is dragged freezing and emaciated aboard a ship from an ice floe in the Arctic Ocean:

‘We accordingly brought him back to the deck, and restored him to animation by rubbing him with brandy, and forcing him to swallow a small quantity. As soon as he showed signs of life, we wrapped him up in blankets…’

Later, the creature attempts to resuscitate a young girl whose body he has dragged from a river: ‘She was senseless; and I endeavoured, by every means in my power, to restore animation…’

Such references recall Lind’s own medical education in Edinburgh under William Cullen, who was instrumental in the early codification of procedures for the revival of drowned or otherwise asphyxiated persons. Cullen is, in fact, mentioned within this context in a medical work known to have been ordered by Percy Shelley from his bookseller in July 1812. Robert Thornton’s Medical Extracts includes a lengthy passage on methods suitable for persons being ‘recalled to life’ from ‘the silent mansions of the tomb,’ and mentions the theories of Cullen and Boerhaave on the causes of death from asphyxiation by hanging. Interestingly, Waldman’s assessment in Frankenstein of modern philosophers as the successors to the alchemists bears similarities to comments in Thornton’s book. Lind’s interest in forensic medicine may be seen as the inspiration for Percy Shelley’s creation of perhaps the earliest example of ratiocinative detective drama in his play The Cenci, and his influence can be found in other of Shelley’s themes.17

Finally, despite the clear objective proof set forward, analyzed, and effectively proving the case for Percy Shelley as the author of Frankenstein, Goulding stops short of taking the next step. One might argue that Goulding’s final deduction is contrary to every point of fact he outlined. Yet, in fairness to Goulding, he is not alone as a scholar whose valuable research simply cannot make the logical step toward Percy Shelley’s authorship of Frankenstein. One can only conclude that there is an unconscious—if not irrational—blindness on the part of many in academia due to the celebrity status of Mary Shelley as the accepted author. Goulding writes,

It is also fascinating to consider how his [Lind’s] ideas, mediated through Percy Shelley and others, worked on Mary Shelley’s imagination.18

And thus the authorship of Mary Shelley remains safely entrenched and guarded by attributing Percy Shelley with supplying his future wife with imagination!

However, the facts are simple. It was Dr. Lind who trained, educated, and encouraged Shelley to pursue his studies in natural and physical sciences, chemical and electrical experimentation, and to continue in the writings of Albertus Magnus and Paracelsus. It was Dr. Lind who exposed Percy Shelley to a laboratory environment where Lind had constructed an earthquake machine, an anemometer, and a “thunder house” for studying Franklin’s lightning rod. Additionally, according to James Bieri, it was also Dr. Lind who suggested using electricity to cure insanity and, possibly for influencing a key idea in Frankenstein, to employ electrical stimulation to animate dead frogs. Coincidentally, being a friend of Captain James Cook, Lind accompanied Sir Joseph Banks on the Royal Society Iceland expedition of 1772.19

Shelley’s years at Eton (1805–1809) only furthered his eccentricities in the use of electrical machines, chemical apparatus, and studies in the relationship of science to human nature. Dr. Lind was the guide to young Shelley, an extraordinary guide for an extraordinary student, a student who would turn his life studies and experiences into an autobiographical science fiction narrative.

If the anonymous author of the 1818 edition of Frankenstein was writing the Preface from the perspective of personal education, interest, and experience, the evidence within the first paragraph of the Preface alone is overwhelmingly indicative of the hand of Percy Bysshe Shelley as its author.

Let us now consider the second paragraph in the Preface to the 1818 first edition and anonymously written Frankenstein:

I have thus endeavoured to preserve the truth of the elementary principles of human nature, which I have not scrupled to innovate upon their combinations. The Iliad, the tragic poetry of Greece — Shakespeare, in the Tempest and Midsummer Night’s Dream, — and most especially Milton, in Paradise Lost, conform to this rule; and the most humble novelist, who seeks to confer or receive amusement from his labours, may, without presumption, apply to prose fiction a licence, or rather a rule, from the adoption of which so many exquisite combinations of human feeling have resulted in the highest specimens of poetry.20

The second paragraph, like the first, is revealing. Moving from Darwin and German physiologists to the writings of Shakespeare, Milton, and the poets of Greece, the anonymous author of the 1818 edition of Frankenstein has indicated another area of his or her education, personal interest, and experience. At first reading it might be argued that Mary Shelley was exposed to such literature from a young age, being the daughter of a highly regarded author, William Godwin. Her own journals describe her as a reader from a young age and exposed to many of the classics, thus perhaps it is too much to argue that this second paragraph from the Preface leans in favor of Percy any more than toward Mary Shelley. Yet, there is one important literary connection that throws the weight for Percy quite over the top in this second paragraph, and it comes from the Preface of Percy Shelley’s epic poem Prometheus Unbound.

The imagery which I have employed will be found in many instances to have been drawn from the operations of the human mind, or from those external actions by which they are expressed. This is unusual in modern Poetry; although Dante and Shakespeare are full of instances of the same kind: Dante indeed more than any other poet and with greater success. But the Greek poets, as writers to whom no resource of awakening the sympathy of their contemporaries was unknown, were in the habitual use of this power…We owe Milton to the progress and development of the same spirit… if this similarity be the result of imitation, I am willing to confess that I have imitated.21

Notice that the author of the 1818 edition Frankenstein Preface as well as the author of the poem Prometheus Unbound admits that he or she is not entirely original, is not an innovator, but relies upon the product of past minds, geniuses who tapped into human emotions or feelings through their words. Specifically Shakespeare, Milton, and the Greek poets are mentioned in both the Frankenstein Preface as well as Prometheus Unbound which was written by Percy Shelley. It is not coincidental, not merely similar, but as sure an intellectual fingerprint as ever might be found in literature when comparing two works of fiction: The Preface to Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus was written by the same author as the Preface to the epic poem Prometheus Unbound; that author is Percy Shelley.

The third paragraph of the anonymously written 1818 first edition of Frankenstein only confirms this conclusion by offering a few more interesting facts worthy of consideration:

The circumstances on which my story rests was suggested in casual conversation. It was commenced, partly as a source of amusement, and partly as an expedient for exercising any untried resources of mind. Other motives were mingled with these, as the work proceeded. I am by no means indifferent to the manner in which whatever moral tendencies exist in the sentiments of characters it contains shall affect the reader; yet my chief concern in this respect has been limited to the avoiding the enervating effects of the novels of the present day, and the exhibition of the amiableness of domestic affection, and the excellence of universal virtue. The opinions which naturally spring from the character and situation of the hero are by no means to be conceived as existing always in my own conviction; nor is any inference justly to be drawn from the following pages as prejudicing any philosophical doctrine of whatever kind.22

Given the previous evidence already presented, it is worthy of notice that the Preface is written as much in terms of autobiography as by way of exposition concerning the text which is to follow in the novel. For instance, notice the wording in the previous paragraph, “the circumstances on which my story rests …” an obvious, though easy to overlook, association linking the story itself to the author of the Preface; this point will be very important to keep in mind.

There is also within the third paragraph of the Preface a curious attempt given by the author to distance himself or herself from any moral, immoral, or philosophical doctrines which could be construed to promote behavior or beliefs suggested in the story, noticeably such damnable ideas as: creation without the hand of God; incest between cousins—or brother and sister as Victor and Elizabeth related to one another; bigamy; scientific experimentation usurping the moral limits of society; or even revolution, a dangerous idea that could be easily interpreted by setting the creature’s birth in the city of Ingolstadt, home of the Bavarian Illuminati.

Such a disclaimer as is made in the third paragraph of the Preface certainly adds intrigue. Although the author would have the reader believe that he or she does not promote any philosophy nor is attempting to uphold or cast down any universal virtues, the Preface is actually baiting the reader, implanting ideas, and at the same time trying to deny any intention for such an agenda. It is subversive, calculated, misleading, and precisely fitting into the pattern of Percy Bysshe Shelley, who had a long record of writing subversive papers anonymously or with a pseudonym, denying any part in the propagation of the work, and yet clearly using every trick in a secret society playbook to accomplish his purpose while maintaining a covert position.

Consider as one dot to connect—and a strangely familiar theme touched upon in the novel Frankenstein—that Shelley’s calculated misdirection and use of anonymity was previously used by him to argue for a belief system of human morality without the need of a Creator; and he did so while outwardly denying his real purpose. As a student at the University of Oxford, Percy Shelley wrote The Necessity of Atheism (1811), an anonymous tract which he not only distributed to the heads of all Oxford colleges but also sent to all of the bishops and select priests in the Church of England. Such intellectual effrontery in executing such a plan while attending an institution—the University of Oxford—which required an oath of faith is evidence of a self-confident covert revolutionary who assumed that he could pull it off and remain unknown as the originator of the tract! In addition to writing the tract, he followed it up with more anti-religious writings designed to be even more misleading. Shelley could not resist a letter campaign using a pseudonym, attempting to draw Anglican clergymen, in essence baiting them, into discussions concerning the same anonymous tract as if he was the one having a crisis of faith after reading the brilliant tract that he himself wrote!23

The modus operandi is identical: choose a controversial theme—one of his favorites, atheism; hide behind anonymity; deny responsibility for the work, and if necessary, write letters pointing those who might suspect his hand in the work to the name of another actual person or substituting a false name.24 To what purpose? Percy Bysshe Shelley did not seek his name in the spotlight nor expect his fame to come to him with recognition and financial gain; rather he worked from behind the curtain to pull off his intellectual and behavioral revolution. Denial of his own work, misdirection, and distancing himself from his own opinions were constants in Shelley’s life. This third paragraph of the Preface actually acts as another proof of his work rather than suggest the hand of anyone else. He wrote, denied his writings, attributed them to another, and kept his head low when or if the bullets began to fly.

And finally, the last two paragraphs of the 1818 Frankenstein Preface are essential pieces to examine with a critical eye for specific historic details. These final paragraphs in the First Edition Preface, set beside the curiously new narrative crafted by Mary for her 1831 Preface, will build a solid case of evidence tampering as it pertains to authorship. If, as is being argued here, Percy Bysshe Shelley is the author of the 1818 anonymous Preface and novel, the details of how the book came to be written might well have had to be altered in order to take a subtle turn away from him and his purposes once the book was later attributed to another person, namely Mary. When she released the 1831 revised edition of Frankenstein she had to present it as if both editions were her own work. And now, the last two paragraphs of the 1818 Preface:

It is a subject also of additional interest to the author, that this story was begun in the majestic region where the scene is principally laid and in society which cannot cease to be regretted. I passed the summer of 1816 in the environs of Geneva. The season was cold and rainy, and in the evenings we crowded around a blazing wood fire, and occasionally amused ourselves with some German stories of ghosts, which happened to fall into our hands. These tales excited in us a playful desire of imitation. Two other friends (a tale from the pen of one of whom would be far more acceptable to the public than any thing I can ever hope to produce) and myself agreed to write each a story, founded on some supernatural occurrence.

The weather, however, suddenly became serene; and my two friends left me on a journey among the Alps, and lost, in the magnificent scenes which they present, all memory of their ghostly visions. The following tale is the only one which has been completed.25

The details in these two paragraphs need to be considered carefully. Pay careful attention to the fact that the occasion on which this story was initiated came about when the author, along with two friends, “agreed to write each a story, founded on some supernatural occurrence.” In total, there are three persons present—the Preface writer and the other two friends. No more, no less. Who were they? Taking a clue from the Preface that “a tale from the pen of one of whom would be far more acceptable to the public than any thing I can ever hope to produce,” it is logical to assume that Frankenstein’s author is referring to none other than Lord Byron, with whom much of the 1816 stormy summer was spent in Switzerland at Byron’s Villa Diodati estate.

By 1816 Lord Byron was a celebrity whose poetry and life made him both famous and scandalous, and unquestionably England’s most popular poet. He had already published the first two cantos of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, and the Byronic hero awakened the public’s love affair with Lord Byron. Thus, by a simple process of elimination, the Frankenstein author was one of the three present during the time of the “agreement” and the second person had to be Lord Byron.

Curiously, the Preface writer suggests that his or her work would be by comparison less “acceptable” to the public. If the argument for Percy Shelley as the author holds true, this would make perfect sense as Shelley was a well-known figure in England for all of the wrong reasons: he was an acknowledged atheist; had been cast out of the University of Oxford for his role in having written The Necessity of Atheism; had run off with two of William Godwin’s adolescent children (Mary and Claire Clairmont) while he was already married; and was considered a young revolutionary.

Four years earlier Shelley had anonymously published several anti-government writings, including A Letter to Lord Ellenborough, which not only argued for freedom of the press but specifically for the right to publish material even if was atheistic. The same year as the Ellenborough letter, 1812, Shelley had published The Devil’s Walk, a poem condemning the British government, the “brainless” King, and the Anglican Church. Percy Shelley protested the harsh economic conditions and shortage of food which was causing great suffering among the poor, and placed blame squarely on the authorities as acting in the very nature of Satan. From this time onward, perhaps even sooner, Percy Shelley was under surveillance from the government.26 In further Illuminati-style covert and subversive manner, Shelley’s manner of distributing his seditious literature was to send them to sea in corked bottles, launch them in hot air balloons, and place them in miniature flotillas at sea.27 Finally, and not so coincidentally as it relates to Shelley’s role in Frankenstein, he had written to his liberal publisher at this time, Thomas Hookham, Jr., requesting approximately seventy books, including Davy’s recently published book on chemistry, Thornton’s Medical Extracts which concerned reviving drowning victims, and Paracelsus’ influence on modern chemistry.28 It is nearly impossible to find a single moment in Shelley’s adult life when revolution, atheism, alchemy, and anonymity were not squarely intertwined and being used in his writings.

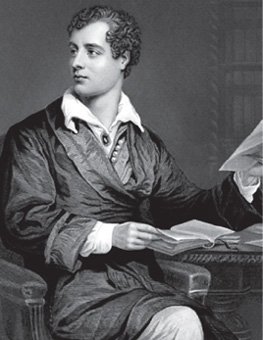

LORD BYRON

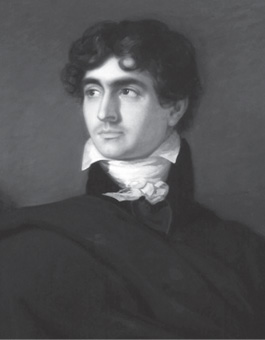

JOHN WILLIAM POLIDORI

And yet, is it possible that Mary Shelley was the one whose writing would be far less “acceptable” to the public than Lord Byron’s? If one argues that a young girl’s writings would be less acceptable than Lord Byron’s, that goes without saying; however, consider what a weak argument it is by comparison! Is that all the anonymous author of the 1818 Frankenstein Preface meant? Surely not.

A final question lingers: who was the third person present when the decision was agreed upon to write a story “founded on some supernatural occurrence”? The choices are limited to the names recorded in the journals which were kept that stormy Switzerland summer in 1816: John William Polidori, Lord Byron’s twenty-eight-year-old physician and struggling writer; Claire Clairmont, Mary’s eighteen-year-old stepsister; or Mary Shelley herself, if indeed Percy Bysshe is the author of the 1818 edition Preface and novel Frankenstein.

The answer is supplied, though the problem is not entirely resolved, by the journal of John William Polidori who wrote that “the ghost-stories are begun by all but me.”29 Therefore, Frankenstein’s author and the writer of the Preface in 1818, Lord Byron, and assumedly John William Polidori, are the most likely three placed together when the decision is made to write their supernatural stories. What of Mary?

1831 PREFACE — MARY THE DECEIVER or THE CO-CONSPIRATOR?

It is not necessary to examine each paragraph, sentence, and word in the 1831 Preface in order to make a case of inconsistencies, or even of a hoax being perpetrated, and a change of hands on the text between 1818 and 1831. The first and most necessary point of fact is that there is no question whatsoever who wrote the 1831 Preface; it was Mary Shelley. Percy Bysshe Shelley had died in 1822 and therefore ruling him out is quite simple. What is necessary to observe is the inconsistency between the two Prefaces as well as one very important admission made by Mary in her 1831 Preface, but more on that later.

Mary Shelley’s Preface (1831) tells a very similar tale, though with some glaring inconsistencies. Observe:

In the summer of 1816, we visited Switzerland, and became the neighbours of Lord Byron. At first we spent our pleasant hours on the lake, or wandering on its shores; …but it proved a wet, ungenial summer, and incessant rain often confined us for days to the house. Some volumes of ghost stories, translated from the German into French, fell into our hands… ‘We will each write a ghost story,’ said Lord Byron; and his proposition was acceded to. There were four of us.30 [emphasis added]

Suddenly another member of the party has been added on the occasion of the decision to write the ghost stories. Is this an oversight? A correction in memory? Or is this a necessary, albeit fabricated, revision in order to make sense of Mary Shelley’s role as the author? Consider three alternatives:

1.) If only three were present on this occasion, as stated in the 1818 version, and if those three were Percy Shelley, Lord Byron, and John Polidori, clearly the most logical three among the five present, it hardly makes sense that an excluded fourth person who was a teenage mistress of Percy Shelley would be so bold as to write her own unsolicited story. This alternative is unacceptable.

2.) If only three were present on this occasion as stated in the 1818 version, and if those three were Lord Byron, Mary Shelley, and William Polidori, it would leave many Frankenstein readers as well as all historians wondering how it could be that Percy Bysshe Shelley, a very accomplished author of prose fiction and poetry, would be excluded in such a gathering, particularly as he and Lord Byron were virtually inseparable! Furthermore, it would open up more than a few nagging questions as to where he was when such a wonderfully challenging literary event was taking shape. This alternative is doomed as well. Percy Shelley must have been present and in the gathering.

3.) If only three were present on this occasion as stated in the 1818 version, and if those three were Lord Byron, Mary Shelley, and Percy Bysshe Shelley, what is the reader to make of the fact that John Polidori records the same event in his journal and completed a story, The Vampyre, which by his own account was written on this occasion? Many readers in 1831 were aware of the fact that Polidori published his story in 1819, therefore it simply defies reason to exclude Polidori from the ghost-story event.

Thus, in order to fabricate the elaborate hoax of Mary Shelley’s authorship, the solution was simple: the events must be changed! The reader is now left with the obvious answer as to why Mary Shelley was obligated to revise the number of people present during the ghost-story event, and yet somehow Claire Clairmont, Mary’s stepsister and the future mother of Byron’s child, is left out of the revised history concerning this moment. Why not just throw in one more name? One wonders if this was an accidental oversight or if it was Mary Shelley’s not-so-gentle revenge on Claire for her ongoing affair with Percy Bysshe Shelley. Either way, the 1831 Preface has now accommodated Mary Shelley at the literary moment when Frankenstein was birthed by Byron’s suggestion.

Mary Shelley continues her 1831 Preface with some additionally unknown details which are worthy of notice:

The noble author began a tale, a fragment of which he printed at the end of his poem of Mazeppa. Shelley, more apt to embody ideas and sentiments in the radiance of brilliant imagery, and in the music of the most melodious verse that adorns our language, than to invent the machinery of a story, commenced one founded on the experiences of his early life. Poor Polidori had some terrible idea about a skull-headed lady … the illustrious poets also, annoyed by the platitude of prose, speedily relinquished their uncongenial task. I busied myself to think of a story,—a story to rival those which had excited us to this task. One which would speak to the mysterious fears of our nature, and awaken thrilling horror—one to make the reader dread to look round, to curdle the blood, and quicken the beatings of the heart. I thought and pondered—vainly. I felt that blank incapability of invention which is the greatest misery of authorship, when dull Nothing replies to our anxious invocations Have you thought of a story? I was asked each morning, and each morning I was forced to reply with a mortifying negative.31

Note what we now have. First, from Mary Shelley’s revised Preface we learn that the other authors, namely Shelley, Byron, and Polidori, failed to live up to the challenge or simply just gave up due to their lack of interest in prose as opposed to poetry. Apparently “poor Polidori” also was mistaken in his account that everyone except him was writing their stories. This second mistake in this 1831 Preface is one of factual detail; it was not Polidori but rather Mary Shelley who was fabricating an entirely new series of events around which she would insert herself as a heroic author struggling against her lack of imagination in a room blessed with that “noble author” (Byron) and the apt and brilliant Shelley who writes with “music of the most melodious verse” that adorns the English language.

Another misleading fact is the explicit statement that the poet Percy Shelley found prose to be an annoyance. The fact is that Shelley’s literary output already included a considerable amount of material other than poetry, including two earlier novels: Zastrozzi, which he wrote in 1809 and which was published in 1810 anonymously with the initials PBS; and also St. Irvyne, or the Rosicrucian, which was published in 1811 anonymously by “A Gentleman of the University of Oxford.” The glaring truth is that Percy Bysshe Shelley was a twice-published novelist prior to Frankenstein and that his method of writing anonymously had not changed, nor had his intention to write fictional novels without drawing attention to himself at the time of Frankenstein.

And finally, a glimmer of reality breaks through the charade when Mary confesses that Shelley wrote, or at least started, his story “founded on the experiences of his early life.” The confession of this truth is critical and easily established by the details we will consider within the story of Frankenstein. But according to Mary Shelley he “relinquished the uncongenial task” due to his annoyance with writing prose. What was relinquished by Percy Shelley was his desire to be associated directly as the author of Frankenstein, and yet his association cannot be ignored as the novel actually reveals the experiences of his life. Mary, acting under and with the fullest cooperation of Percy, attempted to gloss over his role as author by writing a new Preface, putting her own gloss on the events, fabricating facts, and claiming the story as her own in an effort designed to steer the readers away from the belief that Shelley was interested in completing the annoying task. The co-conspirator in this hoax was indeed Mary Shelley.

As Mary Shelley’s revised history unfolds, a familiar story re-emerges, one similar to that which is found in the 1818 Preface:

Many and long were the conversations between Lord Byron and Shelley, to which I was a devout but nearly silent listener. During one of these, various philosophical doctrines were discussed, and among others the nature of the principle of life, and whether there was any possibility of its ever being discovered and communicated. They talked of the experiments of Dr. Darwin … 32

The change is subtle but considerable: Mary is the novice, the learner, the silent disciple who must rely on the expertise of others to fill in the gaps of her academic shortcomings. She is not the one well versed in Darwin. She is not the radical young student studying the writings of Paracelsus and Albertus Magnus, or any other German physiologist. She is, in essence, a fly on the wall attempting to pull in as much information as possible in order to use it in the future. Although the Preface accounts sound similar, the difference is monumental and demonstrates what has already been established, namely, Frankenstein is the product of one who was steeped in science, rubbed shoulders with the men of science, carried on his own experiments at home and in school with friends, family, and wandering animals. The 1818 Preface makes absolute sense when placed within the context of an author who was educated, experienced, and influenced in the fields which set the background for Frankenstein. It makes perfect sense if the author is Percy and not Mary Shelley.

If it were not for the necessity of maintaining Shelley’s hoax, the following sentences penned by Mary Shelley in her 1831 Preface would be remembered in history as among the greatest lies ever committed to ink, one of the worst betrayals committed against another person, the Judas kiss from a novice scribbler to a master poet, for it is an atrociously evil distortion of reality, one which highly suggests how deeply Mary Shelley understood her husband’s desire to remain anonymous:

At first I thought but of a few pages—of a short tale; but Shelley urged me to develope [sic] the idea at greater length. I certainly did not owe the suggestion of one incident, nor scarcely of one train of feeling, to my husband, and yet but for his incitement, it would never have taken the form in which it was presented to the world.33

How can this be? Had Mary Shelley taken complete leave of her senses? Only mere sentences prior to these bewildering statements she has identified that it was in the course of hearing her husband discuss concepts of reanimation, the use of galvanism in modern science, and the writings and experiments of Erasmus Darwin, that she was moved to consider such a subject for her novel. Now, in the midst of remembering with clarity exactly how the book came to her more than a decade earlier, she cannot think of anything whatsoever, not even a train of feeling, which she owes to Percy Shelley. All evidence—even that which is presented by the most committed Mary Shelley scholars who defend her singular genius as the author of Frankenstein, but who must admit that the Frankenstein manuscript corrections were written in Percy Shelley’s own hand—proves that he was more than just the fellow who merely “urged” her to turn a short story into a novel! If ever a gross understatement was written, surely it was when Mary Shelley wrote, “I certainly did not owe the suggestion of one incident, nor scarcely of one train of feeling, to my husband.”

Considering that Mary was well aware of who wrote Frankenstein, and the nonsensical inaccuracy of such statements by her, it must be admitted that she greatly overstated her independent role as the author in order to secure the credibility of her authorship and likewise maintain Percy’s wish to be anonymous. A second, though highly unlikely, possibility is that her father, William Godwin, had more than a small part himself in the revision to the Preface of 1831 and did everything he could to make sure that his former son-in-law was never discovered as the author of Frankenstein, thus guaranteeing his daughter’s fame and the potential monetary gain which he was always seeking to take out of the hand of Percy Shelley. In Shelley’s death William Godwin may have finally found a way to reach deeper into the pocket of the man who eloped with his only natural daughter. The insurmountable problem with this theory is that it leads to the inevitable conclusion that if Mary did not co-conspire with Percy to hide his name from Frankenstein, she in fact did betray him and has stained her integrity beyond repair. This theory I find to be entirely out of character with Mary and therefore dismiss it.

And now for the moment when the curtain is pulled back and the truth is finally revealed. Mary confesses,

From this declaration I must except the preface. As far as I can recollect, it was entirely written by him.34 [emphasis added]

Were it not so obvious from the accumulation of facts presented in the 1818 Preface, this revelation might come as a surprise. All that is lacking is the final confession that the same man (yes, man) who wrote the 1818 first edition Preface for Frankenstein was also the author of the novel, just as he described himself in the preface with the words, “my story …”

For a comparative reading of the two Prefaces, see Appendix A.

1 Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus, J. Paul Hunter, ed., The Original 1818 Text Norton Critical Edition (W.W. Norton and Co.: 1996), p. 5

2 Cf. Transhumanism: A Grimoire of Alchemical Agendas (2012) by Joseph P. Farrell and Scott D. de Hart for a more detailed analysis of manimals and the alchemical agenda behind some modern advances in science.

3 Ibid., p. 5

4 Richard Holmes, Shelley: The Pursuit (E.P. Dutton & Co.: 1975), p. 75

5 Ibid., 75

6 Erasmus Darwin, The Temple of Nature, Canto IV, cf. www.english.upenn.edu/Projects/knarf/Darwin/temple4.html

7 Newman Ivey White, Shelley (Alfred A. Knopf: 1940) Vol. 1, pp. 40–42

8 Carl Grabo, A Newton Among Poets: Shelley’s Use of Science in Prometheus Unbound (University of North Carolina Press: 1930), p. vii. Grabo writes, “The material of this book was planned as a part of the notes to an edition of Prometheus Unbound now in preparation. The scientific citations proved, however, to be so extensive and the need for sketching Shelley’s background so evident, that is independent publication was decided upon.”

9 Ibid., p. 3

10 Ibid., p. xi

11 James Bieri, Percy Bysshe Shelley: A Biography (Johns Hopkins University Press: 2008), p. 50

12 Ibid., p. 50

13 White, vol. 1, pp. 40–41

14 Bieri, p. 65

15 Christopher Goulding, The Royal Society of Medicine (May 2002), cf. textualities.net/christopher-goulding/the-real-dr-frankenstein

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid.

19 Bieri, p. 66

20 Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus, J. Paul Hunter, ed., The Original 1818 Text Norton Critical Edition (W.W. Norton and Co.: 1996), p. 5 (emphasis added)

21 Percy Bysshe Shelley, Shelley’s Poetry and Prose, The Preface to Prometheus Unbound, eds., Donald Reiman and Neil Fraistat (W.W. Norton & Co.: 2002), pp. 207–208 (emphasis added)

22 Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus, J. Paul Hunter, ed., The Original 1818 Text Norton Critical Edition (W.W. Norton and Co.: 1996), pp. 5–6

23 Bieri, p. 104

24 Shelley was known to have used names of friends, i.e. Medwin, and the mailing addresses of friends, to mislead his captive audience. There are few instances when Shelley actually wrote controversial literature and dared to expose himself as the author. Typically, Shelley used the names of acquaintances or pseudonyms in order to publish or write provocative letters.

25 Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus, J. Paul Hunter, ed., The Original 1818 Text Norton Critical Edition (W.W. Norton and Co.: 1996), p. 6

26 Shelley, in writing to his publisher, Hookham, suggested that his controversial literature might be shown to “any friends who are not informers” because of “knowledge I now possess” including fear of government prosecution and of being under surveillance.” Bieri, pp. 216–217

27 Bieri, pp. 217–218

28 Ibid., p. 217

29 William Michael Rossetti, ed., The Diary of Dr. John William Polidori, 1816, Relating to Byron, Shelley, etc. (Elkin Matthew, 1911), p. 125

30 Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus, J. Paul Hunter, ed., The Original 1818 Text Norton Critical Edition (W.W. Norton and Co.: 1996), p. 170

31 Ibid., p. 171

32 Ibid., p. 171

33 Ibid., p. 172

34 Ibid., p. 173