I see by your eagerness, and the wonder and hope which your eyes express, my friend, that you expect to be informed of the secret with which I am acquainted; that cannot be …

— Victor Frankenstein,

Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus, 1818 1st Edition

Anonymous 1

Nearly every great ghost story begins on a dark night, wind whistling through the trees, rain pelting the windows, lightning streaking across the sky, and an image appearing as a shadow in the darkness peering through a window. So it is with Frankenstein as Mary Shelley beckons the reader to imagine how the creature came to her in a waking dream:2

When I placed my head on my pillow, I did not sleep, nor could I be said to think. My imagination, unbidden, possessed and guided me, gifting the successive images that arose in my mind with a vividness far beyond the usual bounds of reverie…I need only describe the spectre which had haunted my midnight pillow. On the morrow I announced that I had thought of a story. I began that day with the words, It was on a dreary night of November, making only a transcript of the grim terrors of my waking dream.

The history behind Frankenstein, as written by Mary Shelley in her 1831 Preface, as we have previously noted, is almost as legendary as the novel itself. Few books have so memorable a history, and perhaps this is the primary reason why so few scholars have been willing to consider an alternative origin for Frankenstein. Reconsider the cinematic quality of the backstory: a stormy summer in Switzerland; a small band of poets—including Lord Byron—and a couple of young girls in a candlelit room; a blazing fire of orange and yellow reflected in the eyes of literary rebels reading German ghost stories; talk of the living dead; eccentric scientists with electrical devices; and a young girl’s waking dream of a spectre. This is pure Hollywood gold in terms of setting up the occasion for a ghost story to end all ghost stories! One might almost imagine that the backstory is as fictional as the creature sewn together from dead tissue and brought to life as a murderous demon.

Mary Shelley’s dramatic 1831 Preface gives the reader precisely what any reader would desire and in so doing she has written a clever cover story and pulled off a skilled act of misdirection, but to what end? While the reader is focused on the creature stirring in the shadows of Mary Shelley’s waking dream, Percy Bysshe Shelley magically disappears from the stormy summer in Switzerland. A literary sleight of hand has effectively removed even the least possibility of linking the name of Percy Bysshe Shelley to the authorship of Frankenstein:

I certainly did not owe the suggestion of one incident, nor scarcely of one train of feeling, to my husband.3

Mary Shelley’s disclaimer concerning her husband’s participation with Frankenstein is explicit, all-encompassing, and oddly reminiscent of the disclaimer found at the end of motion pictures:

All characters appearing in this work are fictitious. Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Not surprisingly, the motion picture disclaimer originated under circumstances in which the characters appearing in the work do in fact bear an uncanny resemblance to real persons.4 Mary Shelley’s attempt to remain true to her husband’s hoax and to shield him from notice as the author could not overcome one major obstacle, namely that of Shelley himself, who bore an undeniable resemblance to characters in Frankenstein. Such an insincere disclaimer in the 1831 Preface should be seen as the most sure indication that those who seek for Percy Bysshe Shelley shall indeed find him.

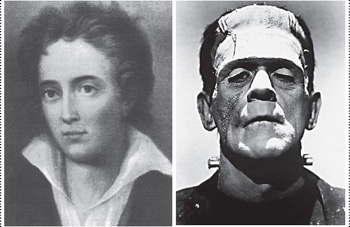

PERCY BYSSHE SHELLEY, AUTHOR OF FRANKENSTEIN (LEFT) FRANKENSTEIN’S “MONSTER” AS PORTRAYED BY BORIS KARLOFF5

In Richard Holmes’ biography Shelley: The Pursuit, the author writes, “implicitly, Shelley accepted his own identification as Frankenstein’s monster.”6 Holmes’ astute observation that Shelley is virtually one and the same with the creature, and that Shelley himself was aware of this fact, nearly defies reason at the point that the author then is incapable or unwilling to accept the reason why a main character is so perfect a literary sketch of Mary’s husband. One wonders why any scholar would be fooled by Mary’s disclaimer after actually reading Frankenstein, the story of an intelligent, isolated, Illuminati-influenced, incestuous young man and student of alchemy whose tutoring in scientific method leads him to envision a world of men without the need of God. Indeed, Holmes was very near the truth when he wrote, “Shelley was well aware of the many autobiographical influences which shaped Mary’s book.”7

Frankenstein is not a horror story. This observation is so self-evident that, as we have previously written, the entire 1831 Preface has been called into question. Although Mary Shelley hoped to misdirect the readers of her 1831 Preface to think of Frankenstein as a waking dream of horrific spectres and a contest-winning ghost story, there was one person who understood and explained the real underlying purpose of Frankenstein: the man who anonymously wrote it, Percy Bysshe Shelley.

In this the direct moral of the book consists; and it is perhaps the most important, and of the most universal application, of any moral that can be enforced by example. Treat a person ill, and he will become wicked. Requite affection with scorn; —let one being be selected, for whatever cause, as the refuse of his kind—divide him, a social being, from society, and you impose upon him the irresistible obligations—malevolence and selfishness. It is thus that, too often in society, those who are best qualified to be its benefactors and its ornaments, are branded by some accident with scorn, and changed, by neglect and solitude of heart, into a scourge and a curse.8

So wrote Percy Bysshe Shelley in 1817 in what would remain an unpublished review of Frankenstein until 1832 when Shelley’s cousin Thomas Medwin presented it for publication in The Athenaeum. The novel, according to Shelley himself, is an indictment against the authoritarian structures in society which use threat, abuse, punishment, and separation or isolation to force obedience and conformity. It is an indictment against the supposed God who created man “in His image” and then terrorized and punished man for his unique nature as a rational independent person. It is an indictment against the God who established boundaries for human society, first in marriage and the family, and then extended into communities, and from those communities arose tyrannous governments and abusive religious institutions. While much more will be said regarding Shelley’s religious views and how they are embedded in Frankenstein, what is critical to observe at this point is that Frankenstein is not a ghost story written to frighten readers with images of fantastic monsters. It is a treatise with a purpose; a story of man’s aspirations and society’s disapproval; Frankenstein is an autobiographical novel inspired by the thoughts and experiences of its author, Percy Bysshe Shelley.

Frankenstein is a series of life stories, narratives weaved together for a common theme. One such narrative is that of an alchemist turned scientist who seeks to offer an alternative to an upside-down and unenlightened world, whose expertise in science unlocks the alchemical goal of transforming the base material of undignified human flesh into a new man, a higher man, a second Adam. Paradise revisited in the garden of Ingolstadt. Frankenstein’s creature is abandoned into a world without love, without compassion, a world of people made in the image of its god. The creature, a stranger and foreigner to this world, must learn how to survive alone in a world without another being who is comparable to it or compatible with it. A new man for a new society, and a new world order created by the hands of an enlightened man—this is the story of Frankenstein! The question then arises: if the story does not originate in the waking dream of Mary Shelley, where does the story of the alchemist turned scientist and creator originate? To answer that question is to return to the childhood of Percy Bysshe Shelley. Newman Ivey White, Shelley’s biographer, accurately wrote, “Of few writers more than Shelley can it be said that his works are the man himself.”9

FRANKENSTEIN AND SHELLEY THE ALCHEMIST

In 1792, Percy Bysshe Shelley was born at Field Place, an isolated country house set on a working farm in Sussex. As a child, Shelley’s imagination took him to places that few children would venture. James Bieri, in his thoroughly documented biography Percy Bysshe Shelley: A Biography, wrote:

One imaginary occupant of Field Place who found an important place in Bysshe’s psyche was ‘an Alchemist, old and grey, with a long beard.’ The young explorer found a spacious garret under the roof where a lifted floorboard gave access to a deserted room where the alchemist lived.10

FIELD PLACE, BIRTHPLACE OF PERCY BYSSHE SHELLEY

This description was supported by Percy Bysshe Shelley’s sister Helen, who remarked, “We were to go see him [the Alchemist] ‘some day’; but we were content to wait and a cave was to be dug in the orchard for the better accommodation of this Cornelius Agrippa.”11 Note that Helen’s choice of an alchemist most associated in her mind to childhood memories of her brother was Cornelius Agrippa, the same influential alchemist whose sudden appearance changes the life of the young Victor Frankenstein:

When I was thirteen years of age, we all went on a party of pleasure to the baths near Thonon: the inclemency of the weather obliged us to remain a day confined to the inn. In this house I chanced to find a volume of the words of Cornelius Agrippa. I opened it with apathy; the theory which he attempts to demonstrate, and the wonderful facts which he relates, soon changed this feeling into enthusiasm. A new light seemed to dawn upon my mind. 12

But this is not the end of Victor Frankenstein’s study of alchemy. Frankenstein’s personal engagement with this pre-scientific discipline is not a mere footnote to the novel but a rather critical theme that underlies the story:

When I returned home, my first care was to procure the whole works of this author [Agrippa], and afterwards of Paracelsus and Albertus Magnus. I read and studied the wild fancies of these writers with delight; they appeared to me treasures known to few beside myself.13

And when Victor determined that he must share his new learning, a study which by most accounts was dangerously associated with man defying God’s laws of nature, creation, and the sanctity of life, he discovered that those nearest him did not share in his enthusiasm. Fairly stated, his relationship to those nearest him were strained:

And although I often wished to communicate these secret stores of knowledge to my father, yet his definite censure of my favorite Agrippa always withheld me. I disclosed my discoveries to Elizabeth, therefore, under a promise of strict secrecy; but she did not interest herself in the subject and I was left by her to pursue my studies alone.14

This alchemy-themed passage deserves special attention, for within it the very soul, mind, and dark memories of its author, Percy Bysshe Shelley, are evident.

Observe that it was the study of alchemy, the practice of which, on the one hand, was exploited by the Church for financial gain and yet also at the same time explicitly condemned by the Church15, that marks a relational distance between Frankenstein and those nearest him. The relationship between alchemy and an implicit atheism among those who practiced it is crucial to mark. The Church condemned the practitioners of alchemy for their dabbling in matters best left to the Church alone, namely promising eternal life and transmuting one substance or essence into another. Only an atheist or heretic would dare to engage in a condemned study or practice, and worse yet Victor Frankenstein dares to share his findings with those around him.

That Victor would disgrace and dishonor his family by straying from the proper social path and deviating from the orthodox standards of religious faith shows much of Percy Shelley in Victor’s character. Note well that it is in Victor’s anti-Christian pursuit of learning that the first evidence of isolation between him and his father occurs. The dark and forbidden study of alchemy would also become a point of emotional distance between Victor Frankenstein and his would-be wife Elizabeth. This autobiographical revelation is worth consideration, as it was while Percy Shelley was attending Oxford University that his relationship with his father, Timothy Shelley, was broken on account of a pamphlet written anonymously by Percy Shelley and his friend Thomas Jefferson Hogg—a pamphlet titled The Necessity of Atheism.

Timothy’s reaction to his son’s newfound conviction was less than encouraging:

Timothy was angered and shamed by his son’s public and provocative display of socially unacceptable ideas. Shelley had exposed his father’s duplicitous religious stance, that private beliefs must not become public if they offend.16

Enraged by his son’s behavior, Timothy appointed a “gentleman” to put Percy back on the proper path with the threat that if his son does not abandon his “errors” and “wicked opinions” the result would be to forfeit his relationship with his father and suffer “punishment and misery for the diabolical and wicked opinions.”17 Could Victor’s fear of his father’s disapproval for studying alchemy have been influenced by the paternal rejection that Percy suffered after publishing his anti-Christian ideas? The answer is self-apparent. It was not Mary Shelley who felt or experienced her father’s rejection for pursuing or publishing ideas which were expressly forbidden by the Church, and it was not Mary who drew down such an experience and penned it into the story of Victor Frankenstein.

And what, if any, parallels link Victor Frankenstein’s isolation from Elizabeth to Percy Bysshe Shelley? In Victor’s case, the confession of his new passion for alchemy was met by his cousin and future wife Elizabeth with disinterest, and led to a solitary pursuit of alchemy; in short, it meant isolation as a consequence for sharing his inner secret knowledge. For Percy Bysshe Shelley, a corresponding experience with that of Victor Frankenstein arises on the occasion when Shelley shares his unorthodox ideas with his would-be wife and cousin, Harriet Grove. The similarities are uncanny and prove the event to be a defining moment in Shelley’s life:

During the years 1809 and 1810 Shelley was not thinking more of his school friendships, studies and dilemmas than of his cousin Harriet Grove. It was felt in the family that he might marry this fresh and pretty girl, to whom (in the words of her brother) he “was at that time more attached than I can express.”… Why then did nothing come of such hopes? … Charles Grove mentions that after the holiday in London, when Shelley and Harriet had resumed their constant correspondence, “she became uneasy at the tone of his letters of speculative subjects.18

Observe:

(1) Both Victor and Percy are to be engaged to their cousins.

(2) Both Victor and Percy felt a sense of security and desire to disclose their newly discovered secret knowledge with their anticipated lifetime companions.

(3) For both Victor and Percy, the cost they paid for revealing their passion in such “speculative subjects” was that both men were left in a state of isolation and abandonment, whether physical or emotional.

Neither Victor nor Percy would ever find a true female companion to fully appreciate or understand their inner thoughts and intellectual pursuits. Percy immediately memorialized his feelings of hurt, anger, and betrayal over this first love lost in a poem included in an anonymously written book titled Original Poetry by Victor and Cazire.

Writing of Harriet’s abandonment, Shelley declares:

Cold, cold is the blast when December is howling,

Cold are the damps on a dying Man’s brow, —

Stern are the seas when the wild waves are rolling,

And sad is the grave where a loved one lies low;

But colder is scorn from the being who loved thee,

More stern is the sneer from the friend who has proved thee,

More sad are the tears when their sorrows have moved

thee, Which mixed with groans anguish and wild

Madness Flow —

As already observed, Shelley also memorialized within the pages of Frankenstein the consequence of sharing his secret knowledge with the one he intended to marry. A simple substitution of names, Elizabeth for Harriet, maintaining the family relation as cousin, and the autobiography is seamless.

And still there is yet another gem hidden within this alchemical passage of Frankenstein which has already yielded a plethora of Victor and Percy associations; it is in Shelley’s choice of words. Let us consider the passage another time from another angle:

And although I often wished to communicate these secret stores of knowledge to my father, yet his definite censure of my favorite Agrippa always withheld me. I disclosed my discoveries to Elizabeth, therefore, under a promise of strict secrecy; but she did not interest herself in the subject and I was left by her to pursue my studies alone. [emphasis added]19

Given that this Frankenstein passage is deeply autobiographical, and that Shelley more than most writers intertwined himself and his experiences into his writing, it is not coincidental that in composing Laon and Cythna or The Revolt of Islam, during 1817, Shelley would echo his feelings with virtually the same words:

And from that hour did I with earnest thought

Heap knowledge from forbidden mines of lore,

Yet nothing that my tyrants knew or taught

I cared to learn, but from that secret store

Wrought linked armour for my soul, before

It might walk for to war among mankind;

Thus power and hope were strengthened more and more

Within me, till there came upon my mind

A sense of loneliness, a thirst with which I pined.20

When one takes into consideration that Laon and Cythna was composed during the same period in which Frankenstein was being written and that Shelley is in a deeply reflective state of mind concerning his boyhood fascination with forbidden alchemical authors and the cost it brought about, namely loneliness and isolation, it stands all the more evident that recurring ideas such as “forbidden mines of lore” and “secret store” and “a sense of loneliness” would match Victor’s desire to communicate “secret stores of knowledge” only to find that he was left by Elizabeth to “pursue [his] studies alone.”

Victor, however, does not let his isolation or emotional abandonment drive him far from his pursuit of knowledge, nor does Shelley abandon his intellectual curiosity in alchemy. As James Bieri observed, “the consuming enthusiasm of the child alchemist of Field Place”21 continued to manifest itself in Shelley’s role-playing, fire-starting, costumes, and chemical experiments.

Carl Grabo asserts that Shelley

…read books on magic and alchemy … presumably through his interest in alchemy he turned early to the no less marvelous possibilities of electricity and chemistry, sciences which at the beginning of the nineteenth century were revealing new worlds to the imaginative mind. He conducted electrical and chemical experiments at home and at Eton where they were forbidden.22

The gradual progression in study from alchemy to the effects of electricity follows a predictable path for a student such as Shelley, and he would make use of these experiences as well when constructing the character of Victor Frankenstein. The pattern is quite clear: what Victor Frankenstein learns and experiences during his tumultuous life must have first taken place in the short and tumultuous life of its author, Percy Bysshe Shelley.

Anne K. Mellor, a noted Mary Shelley scholar, feminist, and Frankenstein expert, acknowledges the link between Shelley’s alchemy and education in scientific uses of electricity and lightning:

Reading Darwin and Davy encouraged Percy Shelley in scientific speculations that he had embarked upon much earlier, as a school boy at Dr. Greenlaw’s Syon House Academy in 1802. Inspired by the famous lectures of Dr. Adam Walker, which he heard again at Eton, Shelley began ten years of experiments with Leyden jars, microscopes, magnifying glasses, and chemical mixtures. His more memorable experiments left holes in his clothes and carpets, attempted to cure his sister Elizabeth’s chilblains with a galvanic battery, and electrified a family tomcat. Shelley early learned to think of electricity and the processes of chemical attraction and repulsion as modes of a single polarized force. Adam Walker even identified electricity as the spark of life itself.23

The association of alchemy, chemistry, and use of electricity for affecting change, whether it be growth, reanimation, or sexual energy, is revealed early in the life of Percy Shelley just as it was in that of Victor Frankenstein:

When I was about fifteen years old, we had retired to our house near Belrive, when we witnessed a most violent and terrible thunderstorm. It advanced from behind the mountains of Jura; and the thunder burst at once with frightful loudness from various quarters of the heavens. I remained, while the storm lasted, watching its progress with curiosity and delight. As I stood at the door, on a sudden I beheld a stream of fire issue from an old and beautiful oak, which stood about twenty yards from our house; and so soon as the dazzling light vanished, the oak had disappeared, and nothing remained but a blasted stump. When we had visited it the next morning, we found the tree shattered in a singular manner… the catastrophe of this tree excited my extreme astonishment; and I eagerly inquired of my father the nature and origin of thunder and lightning. He replied, “Electricity;” he constructed a small electrical machine, and exhibited a few experiments; he made also a kite, with a wire, and string, which drew down that fluid from the clouds.24

Electricity, a key theme, often appeared in Shelley’s poetry in such phrases as “creative fire,” and “liquid love,” or symbolized as the ethereal fluid of creation. The joining of science to alchemy came as a natural development in Shelley’s thinking, first as the alchemist-inspired child at Field Place and later as a Benjamin Franklin experimentalist who had been tutored and lectured to by the most cutting-edge scientists of his day at Syon House and then later at Eton. As noted in the quotation by Anne K. Mellor, Adam Walker was the first to inspire the young Shelley. an inspiration which would have a profound impact on the author of Frankenstein.

ADAM WALKER WITH HIS FAMILY

Adam Walker (1731–1821) was an English inventor, writer, and popular science lecturer. Mainly self-taught, he attended fashionable lectures on experimental philosophy in Manchester and established his own school there in 1762. For publicity he inserted advertisements in local papers and wrote a book entitled Syllabus of a Course on Natural Philosophy (Kendal, 1766). His syllabus covered ‘Astronomy, the use of Globes, Pneumatics, Electricity, Magnetism, Chemistry, Mechanics, Hydrostatics, Hydraulics, Engineering, Fortifications, and Optics.’25 As a lecturer he traveled to Syon House, the middle-class boarding school where Percy Bysshe Shelley spent his first years away from home. Syon House was located in Islesworth, on the Great Western Road in Thames Valley, and there between the years 1802 and 1804 Shelley first heard Dr. Adam Walker. It was on account of Walker’s lectures that Shelley, like Victor Frankenstein, grew from a young alchemist to an avid amateur chemist, natural philosopher, and scientific experimenter. Carl Grabo comments that it was at Syon House that

the transition of his interest from the occult to the scientific is by way of this love for the marvelous, for the new sciences of chemistry and electricity promised greater marvels than alchemy, marvels much more authentic, more possible of immediate realization.26

Likewise, James Bieri notes that “the lectures at Syon House on science and astronomy by the itinerant Dr. Adam Walker left an indelible imprint on Shelley.”27 That imprint most likely included an exposure to Walker’s belief that

[electricity’s] power of exciting muscular motion in apparently dead animals, as well of increasing the growth, invigorating the stamina, and reviving diseased vegetation proves its relationship or affinity to the living principle.28

At Syon House, Shelley was not only taught the principles of reanimating the dead through the use of electricity, but he was also able to furnish himself with the proper apparatus for conducting the experiments which would terrify family, friends, pets, and schoolmates. According to Richard Holmes, it was Adam Walker’s assistant who sold Shelley—or helped him build—his more advanced forms of electrical generators.29

Ian Jackson’s “Science as Spectacle,” in Knellwolf and Goodall’s scholarly work Frankenstein’s Science, observes

By the end of the eighteenth century, some electrical performers and their theories of electricity had become closely associated with social and political radicalism, making their enthusiastic embrace of the seemingly limitless potential of electricity all the more alarming for conservative critics, and all the more inspiring for those, including Percy Shelley (who had been taught by Adam Walker [1731–1821], one of the major radical electrical performers).30

And as to be expected, in the face of the obvious relationship of education and experience linking Percy Shelley to the characters and plot within Frankenstein, Jackson still arrives at the all too common and erroneous conclusion that

indirectly, Mary Shelley’s conception of the plot and key scientific character of the novel was affected by her husband’s studies of the secrets of nature. Percy Shelley was not only fascinated by the task of discovering the prime spark or essence of life but he also demonstrated a taste for the most spectacular manifestations of natural philosophy. This penchant towards the sensational and spectacular, not surprisingly, also characterized Victor Frankenstein.31

Thus, once again Percy Bysshe Shelley’s education, experiences, and memories inadvertently spilled over and became the inspiration for Mary Shelley’s work. Shelley was quite the leaky vessel and Mary was the most fortunate sponge by all such accounts.

Shelley providentially continued his education and slow transformation from young alchemist to scientist under Walker even after Shelley left Syon House Academy for Eton in 1804. The itinerant Walker became a lecturer at Eton during Shelley’s tenure there as well.

Undoubtedly the most important and often overlooked influence on the young Shelley during the adolescent period of his life away from home was Dr. James Lind.

DR. JAMES LIND.

THIS SILHOUETTE IS THE ONLY KNOWN LIKENESS OF LIND.32

James Lind's role in Shelley’s life, as described in the previous chapter, is monumental and worth a second look as it pertains to Shelley as an alchemist-scientist. While Lind is not mentioned in Knellwolf and Goodall’s otherwise thorough book Frankenstein’s Science, Lind’s role as a contributor to the characters and plot in Frankenstein cannot be so easily dismissed. It was Dr. Lind, even more so than Dr. Walker, who guided and molded Shelley into becoming and imagining all that Frankenstein as a novel would come to represent. If, as it is argued, Frankenstein reflects the life, education, and experiences of Percy Bysshe Shelley, it follows that the men who influenced him the most would also be reflected most in his novel. The role that James Lind occupies in the formation of Percy Shelley is best revealed in Shelley’s own words:

This man … is exactly what an old man ought to be. Free, calm-spirited, full of benevolence, and even of youthful ardour; his eye seemed to burn with supernatural spirit beneath his brow, shaded by his venerable white locks; he was tall, vigorous, and healthy in his body; tempered, as it had ever been, by his amiable mind. I owe that man far, ah! Far more than I owe to my father; he loved me and I shall never forget our long talks where he breathed the spirit of the kindest tolerance and purest wisdom.33

James Lind (1736–1812) was a Fellow of the Royal Society, physician to the royal household, a philosopher, inventor, scientist, and pamphleteer. More importantly, Lind was a virtual alchemist himself whose passionate interest in pushing scientific limits earned him the description as a “latter-day Paracelsus.”34 James Bieri writes that Lind’s

apparatus-filled study—embodied Shelley’s childhood fantasies of the attic alchemist of Field Place … Lind’s influence may have extended to introducing Shelley to—or encouraging further study of Plato, Pliny, Lucretius, Paracelsus, Albertus Magnus, and Condorcet.35

The mention of Paracelsus and Albertus Magnus in relationship to Lind’s influence on Shelley marks a clear indication that Lind and Frankenstein are united further than most researchers have ventured to admit.

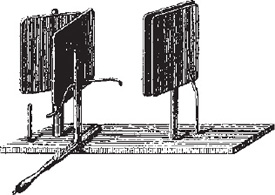

THE CAVALLO MULTIPLIER

As briefly noted in the previous chapter, The Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine in 2002 published an intriguing and insightful article by Christopher Goulding, M.Litt., titled “The Real Doctor Frankenstein.” In the article, Mr. Goulding argues that in spite of recent Mary Shelley biographies which attempt to provide evidence of Mary’s exposure to medical or scientific ideas, “… a reassessment of certain other medical themes and quasi-autobiographical events featured throughout Frankenstein might now be said to suggest the influence of Lind’s character and work, via his pupil Percy Shelley.” 36

Goulding’s methodical examination of the ties connecting Lind to Frankenstein is insightful and demands attention. Among the critical points of contact are Lind’s contacts with Tiberio Cavallo (1749–1809), a noted Italian physicist and natural philosopher who invented the so-called Cavallo Multiplier, a device used for the amplification of small electric charges.

Between 1782 and 1809 Cavallo and Lind made a regular exchange of correspondence, in particular related to the question of Lind reanimating dead frogs. On July 11, 1792, Cavallo writes, “have you made any dead frogs jump like living ones,” and on August 15 of the same year writes, “I am glad to hear of your success in the new experiments on muscular motion and earnestly entreat you to prosecute them to the ne plus ultra of possible means.”37 Further, Lind’s medical training in Edinburgh with William Cullen (1710–1790), a Scottish physician, chemist, and professor at Edinburgh Medical School, reveals Lind’s background in procedures for reviving a drowned or asphyxiated person. Cullen’s work in this area was the established theory which was contained in Robert Thornton’s Medical Extracts, a book which was ordered by Percy Shelley from his bookseller in 1812. The obvious relationship to Frankenstein is found in the revival of Victor Frankenstein when he is dragged, freezing and emaciated, aboard Walton’s ship in the Arctic Ocean:

We accordingly brought him back to the deck and restored him to animation by rubbing him with brandy, and forcing him to swallow a small quantity. As soon as he shewed signs of life, we wrapped him up in blankets, and placed him near the chimney of the kitchen-stove. By slow degrees he recovered, and ate a little soup, which restored him wonderfully.38

Understandably, Shelley was indebted to Lind for placing in his hands the medical background to conceive of using electricity to animate and reanimate animals, to revive those who had drowned or were near death from exposure to the elements, and also for bestowing on him the certainty that alchemical principles could be joined to modern scientific methods. To create, to heal, to resurrect; these possibilities were not so far separated from man and could be achieved without the aid of God and thereby effect a transformative change on mankind. Shelley’s agenda, though deemed blasphemous to contemplate, would be unveiled for all to see in his writings and dangerous experiments.

Shelley’s closest friend, Thomas Jefferson Hogg, provides a fitting and shocking illustration of how far Percy was willing to go with his childhood alchemical dreams joined to modern uses of electricity:

He [Shelley] then proceeded, with much eagerness and enthusiasm, to show me the various instruments, especially the electrical apparatus; turning round the handle very rapidly, so that the fierce, crackling sparks flew forth; and presently standing upon the stool with glass feet, he begged me to work the machine until he was filled with the fluid, so that his long, wild locks bristled and stood on end. Afterwards he charged a powerful battery of several large jars; labouring with vast energy, and discoursing with increasing vehemence of the marvelous powers of electricity, of thunder and lightning; describing an electrical kite that he had made at home, and projecting another and an enormous one, or rather a combination of many kites, that would draw down from the sky an immense volume of electricity, the whole ammunition of a mighty thunderstorm; and this being directed to some point would there produce the most stupendous results.39

The question that the reader must ask again and again throughout this book is whether Frankenstein as originally penned anonymously in 1818 reflects the distinctive education and highly unusual personal experiences of Percy Bysshe Shelley (which he fictionalized into the novel and later credited to his wife in order to veil himself); or whether Frankenstein is a mere ghost story concocted in a waking dream by Mary Shelley, without the slightest “suggestion of one incident, nor scarcely of one train of feeling, to [her] husband.” If the latter is true, Mary’s gifts went far beyond writing; it must be admitted that her psychic abilities tapped so deeply into Shelley’s past, without the slightest indication of his cooperation or awareness of it, that she virtually acted as a medium and channeled his memories and experiences. This indeed would be quite an accomplishment!

ALASTOR: OR, THE SPIRIT OF SOLITUDE

December 14, 1815

I have made my bed in charnels and on coffins,

Where black death keeps record of the trophies won from thee,

Hoping to still these obstinate questionings

Of Thee and thine, but forcing some lone ghost,

Thy messenger, to render up the tale of what we are.

In lone and silent hours,

When night makes a weird sound of its own stillness,

Like an inspired and desperate alchymist

Staking his very life on some dark hope,

Have I mixed awful talk and asking looks

With my most innocent love,

Until strange tears, uniting with those breathless kisses made

Such magic as compels the charmed night

To render up thy charge …

1 Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus, J. Paul Hunter, ed., The Original 1818 Text Norton Critical Edition (W.W. Norton and Co., 1996), p. 31

2 Ibid., (Preface, 1831) p. 172

3 Ibid., (Preface, 1831) p. 172

4 The 1932 MGM movie Rasputin and the Empress insinuated that the character Princess Natasha had been raped by Rasputin. Princess Natasha’s character was supposedly intended to represent Princess Irina of Russia, and the real Princess Irina sued MGM for libel. After seeing the film twice, the jury agreed that the princess had been defamed.

Cf. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/All_persons_fictitious_disclaimer

5 Promotional photo of Boris Karloff from The Bride of Frankenstein as Frankenstein’s monster: public domain image from commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Frankenstein%27s_monster_(Boris_Karloff).jpg

6 Richard Holmes, Shelley: The Pursuit (E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1975), p. 334

7 Ibid., p. 334

8 Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus, J. Paul Hunter, ed., The Original 1818 Text Norton Critical Edition (W.W. Norton and Co, 1996), p. 186

9 James Bieri, Percy Bysshe Shelley: A Biography (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008) Preface, p. xi

10 Ibid., p. 37

11 Ibid., p. 37

12 Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus, J. Paul Hunter, ed., The Original 1818 Text Norton Critical Edition (W.W. Norton and Co., 1996), p. 21

13 Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus, J. Paul Hunter, ed., The Original 1818 Text Norton Critical Edition (W.W. Norton and Co., 1996), p. 22

14 Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus, J. Paul Hunter, ed., The Original 1818 Text Norton Critical Edition (W.W. Norton and Co., 1996), p. 22

15 In 1317 Pope John XXII issued a decree against the alchemists De Crimine Falsi Titulus VI. I Joannis XXII.

16 Bieri, p. 128

17 Ibid., p. 129

18 Edmund Blunden, Shelley, A Life Story (The Viking Press, 1947), pp. 45–46

19 Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus, J. Paul Hunter, ed., The Original 1818 Text Norton Critical Edition (W.W. Norton and Co., 1996), p. 22

20 Donald H. Reiman and Neil Fraistat, eds., Shelley’s Poetry and Prose (W.W. Norton & Co., 2002), p. 102

21 Bieri, p. 37

22 Carl Grabo, Shelley’s Eccentricities (University of New Mexico Press, 1950), pp. 8–9

23 Anne K. Mellor, A Feminist Critique of Science, homepage.ntlworld.com/chris.thorns/resources/Frankenstein/A_Feminist_Critique_of_Science.pdf

24 Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus, J. Paul Hunter, ed., The Original 1818 Text Norton Critical Edition (W.W. Norton and Co., 1996), pp. 22–23

25 cf. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adam_Walker_(inventor)

26 Carl Grabo, A Newton Among Poets (University of North Carolina Press, 1930), p. 4

27 Bieri, p. 50

28 Adam Walker, System of Familiar Philosophy: In Twelve Lectures (London, 1799), p. 391; original emphasis is retained.

29 Holmes, p. 16

30 Ian Jackson, contributor, Christian Knellwolf and Jane Goodall, editors, Frankenstein’s Science: Experimentation and Discovery in Romantic Culture, 1780–1830 (Ashgate, 2008), p. 152.

31 Ibid., p. 152

32 Image of Lind found at www.jameslind.co.uk, a website maintained by Christopher Goulding

33 Thomas Jefferson Hogg, The Life of Percy Bysshe Shelley, 2 volumes. 1858. Op cit. Richard Holmes, Shelley: The Pursuit, p. 28

34 Bieri, p. 65

35 Ibid, pp. 65–66 (emphasis added to original quotation)

36 Christopher Goulding, “The Real Doctor Frankenstein?” published in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 2002 May; 95(5): 257–259. Online article: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1279684

37 Ibid.

38 Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus, J. Paul Hunter, ed., The Original 1818 Text Norton Critical Edition (W.W. Norton and Co., 1996), p. 14

39 Holmes, pp. 44–45