PERCY SHELLEY, FRANKENSTEIN, AND ATHEISM

Oh how I wish I were the Antichrist.1

— Percy Bysshe Shelley

The story of Frankenstein is a subtle, albeit powerful, manifesto for atheism in the hands of Percy Shelley. At first glance such a claim may seem far-fetched, perhaps forced; however, a careful reading of Frankenstein reveals that Shelley had every intention to espouse his conviction regarding the dangers of religion, specifically the Christian faith. From an early age Shelley determined that he would expose and covertly attack the Church as an instrument of terror, injustice, and hypocrisy. Frankenstein stands as his most cleverly concealed literary attempt to effect an awakening by undermining credibility in the Christian faith. Shelley vowed,

Oh! I burn with impatience for the moment of Xtianity’s [sic] dissolution, it has injured me; I swear on the altar of perjured love to revenge myself on the hated cause of the effect which even now I can scarcely help deploring — Indeed I think it is to the benefit of society to destroy the opinions which can annihilate the dearest of its ties … I will stab the wretch in secret. Let us hope that the wound which we inflict tho’ the dagger be concealed, will rankle in the heart of our adversary.2

Although these words do not make any explicit reference to the writing of Frankenstein, they do in fact reveal his ultimate goal as an author: to secretly destroy Christianity and drive a fatal dagger into it by means of his writings. Assuming Percy Shelley to be the author of Frankenstein, the novel ought to reveal something of Shelley’s atheistic vow in the previous cited quotation.

AN ATHEIST AND AN ANGLICAN PRIEST

Shelley’s revolutionary and atheistic agenda openly manifested itself shortly after he began his studies at the University of Oxford in 1810. Determined to rid the world of tyranny, Shelley could identify no greater target deemed more oppressive to human freedom than the Christian religion. Shelley began a calculated and systematic plan to bait Anglican clerics into discussions with him by mailing seemingly innocent letters to his chosen ecclesiastical pawns. These letters, if replied to, would provide Shelley with a theological and intellectual punching bag upon which to try out his arguments.. This research into Christian apologetics prepared the ground for much of the atheistic works which would soon follow. Shelley wanted first-hand evidence as to how England’s best clergymen and theologians would respond to ostensibly sincere requests for answers from a person struggling to believe the Christian faith. The responses to his pseudonymously written letters to the clergymen enabled Shelley to align his intellectual crosshairs squarely on his religious targets; the end result of Shelley’s cat-and-mouse game was his tract The Necessity of Atheism, anonymously published in 1811.

It is curious that The Necessity of Atheism is less atheistic than it is a challenge to theists to acknowledge that belief is a human passion, and as such cannot stand up to the test of being reasonable, thus the necessity or reasonableness of atheism. Atheism, in Shelley’s case, is an argument for human reason to be given preeminence over passions, which are always subjective, lacking reasonable proof, and therefore can not be enforced upon any free person. Newman Ivey White summarizes Shelley’s tract accurately, writing

Except for the title and the signature to the advertisement (“through deficiency of proof, an Atheist.”) there was no atheism in it. In its seven pages of text it argued that belief can come only from three sources: physical experience, reason based on experience, and the experience of others, or testimony. None of these, it argued, establishes the existence of a deity, and belief, which is not subject to the will, is impossible until they do. Hence the existence of a God is not proved.3

Shelley’s words were temperate, reasoned, and yet also revolutionary at the beginning of the nineteenth century, a century still reeling from the effects of the American War for Independence and the French Revolution:

The mind cannot believe the existence of a creative God: it is also evident that, as belief is a passion of the mind, no degree of criminality is attachable to disbelief; and that they only are reprehensible who neglect to remove the false medium through which their mind views any subject of discussion. Every reflecting mind must acknowledge that there is no proof of the existence of a Deity.4

It did not take long before Percy Bysshe Shelley was found out and brought before the Master of University College, Oxford, Rev. James Griffith. Shelley was questioned amidst much anger from the Master of the college concerning his part in writing the anonymous atheistic tract. Shelley’s response to Griffith was,

If I can judge from your manner … you are resolved to punish me, if I should acknowledge that it is my work. If you can prove that it is, produce your evidence; it is neither just nor lawful to interrogate me in such a case and for such a purpose. Such proceedings would become a court of inquisitors, but not free men in a free country.5

And with his patriotic appeal for evidence to be produced, Percy Bysshe Shelley was expelled from the University of Oxford. Before the University gates could slam behind him, Shelley had already sent the tract on atheism to all of the bishops, and apparently to many professors, heads of colleges, the Vice Chancellor, and at least one Cambridge professor.6 Ironically, in the grand tradition of sanctifying sinners into saints—if such men or women achieve fame after their deaths—a monument now resides at University College, Oxford, to pay homage to the University’s most famous expelled atheist.

For Shelley, however, still being quite alive in 1811 and not so saintly as death would later make him, this event only tempered his steel and focused his aim for future literary projects. He learned from this event that greater care must be taken to remain anonymous, to conceal his agenda, and to mislead those who were most likely to assume his part in such future affairs. Writing to his co-laborer in the infamous Necessity of Atheism tract, Thomas Jefferson Hogg, Shelley revealed his new design, a plan in which Shelley would suggest to the public that he had given up writing:

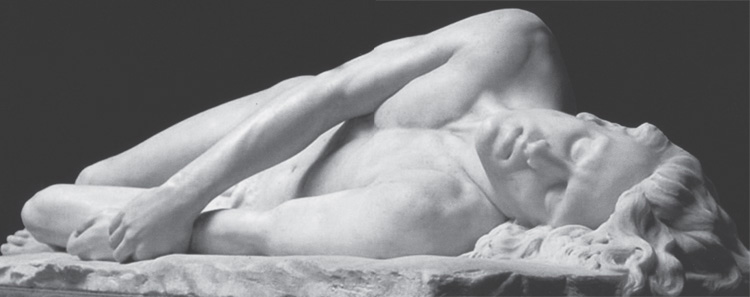

PERCY BYSSHE SHELLEY MEMORIAL, UNIVERSITY COLLEGE, OXFORD

…I give out therefore that I will publish no more; every one here, but the select few who enter into its schemes believed my assertion. 7

Of course nothing was further from his mind than to abandon his vow to thrust his dagger deeply into the heart of the Christian faith. From this point forward Shelley would guard his “schemes” among the select few who could be trusted and he would learn even better how to apply the principles of a quiet revolution. He reasserted his vow to Hogg, exclaiming, “yet here I swear and if I break my oath may Infinity Eternity blast me, here I swear that never will I forgive Christianity.”8

Within a year Shelley struck again in a privately distributed, though initially unpublished, poem titled Queen Mab. Whereas The Necessity of Atheism relied on a reasoned and logical appeal to the reader, Queen Mab took aim at the heart. Speaking in the voice of God, a powerful literary device calculated to shock his selected reader into dread or into an alarmed state of reasonable doubt concerning the schizophrenic nature of the God of Holy Scripture, Shelley [or God, if you dare] declares:

From an eternity of idleness

I, God, awoke; in seven days’ toil made earth

From nothing; rested, and created man:

I placed him in a paradise, and there

Planted the tree of evil, so that he

Might eat and perish, and my soul procure

Wherewith to sate its malice, and to turn,

Even like a heartless conqueror of the earth,

All misery to my fame. The race of men

Chosen to my honor, with impunity

May sate the lusts I planted in their heart.

Here I command thee hence to lead them on,

Until, with hardened feet, their conquering troops

Wade on the promised soil through woman’s blood.

And make my name be dreaded through the land.

Yet ever-burning flame and ceaseless woe

Shall be the doom of their eternal souls,

With every soul on this ungrateful earth,

Virtuous or vicious, weak or strong, — even all

Shall perish, to fulfil [sic] the blind revenge

(which you, to men, call justice) of their God.9

And to drive the dagger of atheism in deeper, Shelley added the following advice in his notes accompanying the poem:

Religion and morality, as they now stand, compose a practical code of misery and servitude: the genius of human happiness must tear every leaf from the accursed book of God ere man can read the inscription on his heart.10

By 1813 Shelley had arrived at the conclusion that “reason” is inherent to human nature, it is objectively verifiable, and resonates within the fiber of each living person, and therefore the most capable means of moving the senses and will to act. Logic paired with a strong emotional appeal was well suited for his poetry, and this was precisely the purpose and effect of Queen Mab.

PRE-FRANKENSTEIN ATHEISTIC AND ALCHEMISTIC FICTION

And it was not only atheistic poetry that Shelley made use of at this time; he also put his hand to writing godless fiction. His short novels Zastrozzi (1810) and St. Irvyne, or the Rosicrucian (1811), though largely unnoticed by the public—aside from a few condemning reviews11—proved suitable mediums for testing his hand at infusing atheistic and alchemistic themes into fiction. In these first works of fiction Shelley developed characters, settings, and plots which would reappear in a more advanced form only a few years later during a stormy summer in Geneva.

A cursory overview of St. Irvyne (1811) bears an uncanny similarity to Frankenstein. Consider a few overlapping points of interest: a solitary wanderer through the Alps; characters settled in Geneva; a mysterious dark figure who is always nearby and yet elusive; deceptions which lead to murder; and an alchemist whose studies lead him to the discovery of eternal life. This cannot be coincidental!

Shelley’s earliest atheistic and alchemistic fiction demonstrates Frankenstein was not birthed in the context of a young girl’s waking dream, it was a seed germinating in Shelley’s mind and leaking from his quill for many years; more importantly, it was the story of his own life and convictions. Shelley’s final novel, Frankenstein, a far more advanced alchemistic and atheistic work, would be his unacknowledged crowning achievement, for in this novel he could fictionalize all of his mature experiences, education, and atheistic propaganda in a single opus.

PROMETHEUS AND STEALING GOD’S FIRE: SHELLEY’S ATHEISM TAKES SHAPE

The subtitle to Frankenstein is the first indication that the novel is intended as a challenge to the Christian god. The Modern Prometheus harkens the reader of Frankenstein to a remembrance of the Greek titan Prometheus, who was chained and tortured for stealing fire from Zeus in order to give light to humanity as well as for his thwarting of Zeus’ plan to annihilate the human race. One can hardly mistake the modus operandi of Percy Shelley even in the subtitle of Frankenstein. Who more clearly could identify with the rebellious Prometheus than Shelley, who had been stealing God’s fire since his days at Oxford?

As early as 1810, when Shelley matriculated to the University of Oxford, he was engaged in the reading of Aeschylus’ Prometheus Bound, and mere months before undertaking Frankenstein during the stormy summer of 1816 Shelley was once again reading as well as translating Aeschylus’ Greek version of Prometheus Bound. Shelley’s initial interest, timed conveniently to his writing of The Necessity of Atheism, as well as his return to the Prometheus myth in its original language—alongside the writing of Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus—suggests more than coincidence. Equally noteworthy is the fact that Shelley’s attachment to this atheistic and revolutionary theme carried over after the completion of Frankenstein in 1818 when he began his four-act play Prometheus Unbound in October of the same year.

The atheism and social revolution that Shelley subtly embedded in Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus plot would reappear in his far less subtle four-act play Prometheus Unbound, a virtual commentary behind the ideas veiled in his novel. In his Preface to Prometheus Unbound, Shelley again acknowledges his underlying purpose as an author, a purpose as true for his four-act play as it is for his 1818 novel Frankenstein:

Poets, not otherwise than philosophers, painters, sculptors, and musicians, are in one sense the creators and in another the creations of their age… let this opportunity be conceded to me of acknowledging that I have, what a Scotch philosopher characteristically terms, ‘a passion for reforming the world.’12

Shelley saw his literary purpose as that of a creator and reformer, and therefore used the revolutionary Promethean theme of a lesser being challenging the authority of God to enlighten and save the human race. What is surprising is that so few scholars have taken Shelley at his word and acknowledged that his life and literary purpose was to effect a reformation and create a new, alchemically inspired society without the need of God. What could be more fitting to style his literary agenda upon than Prometheus’ defiance of Zeus?

A DIGRESSION: SHELLEY’S WORDS, MARY’S HAND

An incalculably important, though seemingly tangential, detail as it relates to the procedure Shelley used in writing for publication was his habit of employing Mary in the transcribing process. The final Frankenstein transcripts sent to press were penned in Mary Shelley’s hand and for this reason are generally promoted as a final nail-in-the-coffin argument for Mary’s authorship of the novel. Yet as Reiman and Fraistat acknowledge in Shelley’s Poetry and Prose,

Mary Shelley transcribed for the press most or all of Acts I–III [Prometheus Unbound] between September 5 and 12, 1819, and all of Act IV in mid-December 1819. As was his usual practice, Shelley appears to have corrected the press transcripts, making a series of small final revisions to prepare the poem for the press.13

There is no logical rationale for assuming that Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus was written and transcribed in any other fashion than that which Reiman and Fraistat admit was Shelley’s “usual practice,” namely Shelley created and wrote his first drafts (or on occasion dictated them14) while Mary took on the role as his final transcriber. Curiously, this well-known practice of Shelley’s continues to be intentionally overlooked by Frankenstein scholars who merely count the few thousand words that Shelley corrected in the Frankenstein press transcript.

In 2008 Charles E. Robinson applied this defective method of ignoring Shelley’s “usual practice” when he graciously credited Percy Bysshe Shelley with a minimal 4,000- to 5,000-word contribution to Frankenstein.15 Why, one may ask, is it “his usual practice” when Shelley makes “small final revisions” to Prometheus Unbound—as well as many other works—and then remarkably it is no longer Shelley’s “usual practice” when his hand makes minimal corrections to Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus? The reader would do well to pay diligent attention to this point while reassessing the evidence behind the 1818 anonymously published first edition of Frankenstein.

The fact that Frankenstein became shrouded beneath the thinly fabricated veil of Mary’s authorship greatly assisted Shelley’s intention to attack his victim, Christianity, without notice. It is the primary thesis of this book that the fundamental reason Percy Bysshe Shelley perpetrated the hoax of Mary Shelley as Frankenstein’s author was his calculated agenda to initiate his alchemical and atheistic social revolution without suspicion or detraction from the novel by association with his name and atheistic reputation. Had the name of England’s most notorious atheist been attached to Frankenstein, his anti-Christian revolutionary agenda would have been far more obvious and consequently far less effective. A terrorist’s or revolutionary’s most powerful weapon is in the ability to remain anonymous and unpredictable. For Percy Bysshe Shelley, his war was one without guns or knives but with a sharp wit and a quill, yet all the same it was a personal engagement against an enemy: against those he considered agents of tyranny, in particular the Church, and his success demanded that he be covert in his operations.

THE HIDDEN ATHEISM IN FRANKENSTEIN

The question now must be asked, how did Shelley covertly weave his atheistic agenda into the literary fabric of Frankenstein? In two subtle though identifiable ways: the first and more easily observed one was to create a plot in which a single man achieves the high and blasphemous act of creating life without the participation of God. Victor Frankenstein accomplishes through his childhood study of alchemy and his university education in modern science a feat which only God could have been capable of achieving—the grand gift of giving life. Note, it is the spark of electricity rather than the breath of the Holy Spirit which bestowed life. Nature in effect supplanted God and, consequently, man’s ability to harness nature’s power was, in effect, to enthrone man at the highest position in all of creation. The threat of an angry god could no longer be used to tyrannize and force mankind into submission. A knowledge of nature with all of its beauty and possibilities would, if scientifically applied, naturally liberate mankind from the domination of priests, bishops, and the governments which acted in collusion with the Church. Frankenstein was the catalyst for revolution if only Shelley’s readers could read between the lines.

One might argue that if this was Shelley’s intended agenda, why would the novel end in Victor Frankenstein’s apparent failure? Is this not counterproductive to Shelley’s purpose? Quite the opposite is true. Shelley cleverly answers this anticipated dilemma in his own review of the work that he authored:

In this the direct moral of the book consists; and it is perhaps the most important, and of the most universal application, of any moral that can be enforced by example. Treat a person ill, and he will become wicked. Requite affection with scorn; — let one being be selected, for whatever cause, as the refuse of his kind — divide him, a social being, from society, and you impose upon him the irresistible obligations — malevolence and selfishness. It is thus that, too often in society, those who are best qualified to be its benefactors and its ornaments, are branded by some accident with scorn, and changed, by neglect and solitude of heart, into a scourge and a curse.16

One can hardly miss the autobiographical content in Shelley’s review of Frankenstein. He had experienced beatings and bullying while at Syon Academy and Eton on account of his feminine or androgynous demeanor and appearance; been labeled “mad” and “dangerous” by his peers and those in authority over him during his adolescence; was ostracized by his sisters, threatened with disinheritance by his father; expelled from the University of Oxford; attacked by the press for his radical ideas and writings; and lived most of his short life misunderstood by those around him. Shelley was the very image of the fiend, the creature, the unwanted “refuse of his kind” who might have been a benefactor to mankind but instead became its curse. The message and moral is quite clear: Frankenstein’s creature was not the failure, but rather, society’s inability to live in harmony with nature while submitting to the irrational authority of a divinity was the primary cause of evil, the actual failure. Society under the dominating authority of religion is what is truly monstrous. For Shelley, God’s being, laws, and threats are unnecessary for the establishing of morality in mankind; there is no need to blame “the devil” for society’s ills. The fault lies squarely on society for its refusal to act in accordance with nature and with respect to its inherent goodness. The creature in Frankenstein bears responsibility for his actions but one must concede that, had the “fiend” been treated in accordance with the love that was due to it at the moment of its self-awareness, the creature of Victor Frankenstein would have understood, experienced, and reciprocated goodness rather than evil. Shelley’s moral philosophy was expressed poetically in Peter Bell the Third:

The Devil, I safely can aver,

Has neither hoof, nor tail, nor sting;

Nor is he, as some sages swear,

A spirit, neither here nor there,

In nothing—yet in everything.

He is—what we are;17

The second manner in which Frankenstein thrusts Shelley’s atheistic dagger at the heart of Christianity occurs when Justine, the Frankenstein household’s servant, is falsely accused of the murder of young William, Victor’s brother. Only days after making a case for herself in court, arguing that she had been framed and evidence had been planted on her by the actual murderer—whoever he/she/it was—Justine makes a sudden and inexplicable reversal. Much to the horror of the Frankenstein family, Justine confesses to the murder when in fact she is innocent. After Justine is pressed by Victor and his sister-like cousin and future wife Elizabeth to explain why she has now reversed herself and confessed to the murder, Justine declares,

I did confess; but I confessed a lie. I confessed, that I might obtain absolution; but now that falsehood lies heavier at my heart than all my other sins. The God of heaven forgive me! Ever since I was condemned, my confessor has besieged me; he threatened and menaced, until I almost began to think that I was the monster that he said I was. He threatened excommunication and hell fire in my last moments, if I continued obdurate… In an evil hour I subscribed to a lie; and now only am I truly miserable.18

In a clever and unsuspecting manner, Shelley finds a way to bypass and undermine the strongest defense mechanism of the faithful: that implicit trust which refuses to believe the Church could err; the Church is, after all, the earthly voice and tribunal for God. The reader, now sympathizing with Justine, has been compelled to see reality from a new perspective and thereby feels repulsion toward the Church and empathy for a poor servant. Justine, as a Shelleyan analogy for all of the oppressed servants of a false god, does the unthinkable and betrays her own conscience in hopes of escaping excommunication and hellfire. The moral dilemma is apparent, and the human heart responds; the mind of each reader is engaged to ask, why would the Church or a benevolent god exercise such emotional torture against his own creation? What are the consequences of betraying one’s own conscience? In this well-contrived episode Shelley introduces his own parable with Justine as the sheep led to the slaughter by clergy acting in the capacity of God’s messengers of doom. The effect is an emotional shock and an awakening of human reason as Shelley planned it. The reader is compelled to do the unthinkable—to judge the moral authority of the Church on account of its egregious crime against Justine. In the priest’s coercing of this innocent servant to confess to a crime which she did not commit, the Church is exposed for its abuse and tyranny over the innocent with its threat of eternal punishment. Utilizing its authority to speak with the voice of God, Shelley anticipates that the reader will awaken to see the Church as an unnecessary and inhumane tyrannous institution perpetually inflicting torture on humanity, while furthering its own self-appointed and incontestable position to remain the moral referees holding the power to grant eternal life or threaten eternal punishment; the keys of Saint Peter, to bind or to loose on earth as in heaven. Shelley, the atheist, accomplished his purpose with hardly being noticed. The story might well have been written with Justine being framed and executed for a crime committed by the fiend without the need to introduce this twist of a false confession. However, by inserting this twist and turning the reader against the Church, opening the eyes of the readers to question the moral authority of the Church, Shelley has hit his mark and the dagger is lodged deeply into the heart of his truest enemy, the Christian church.

The fiend murdered young William in his rage against his maker, but how does one explain the Church standing equally guilty for the execution (murder) of innocent Justine? In Shelley’s subtle way, the fiend elicits the reader’s sympathy, or at least understanding, while the Church finds no sympathy whatsoever and becomes the greater monster in the novel.

In one additional atheistic-tilting episode described in Volume 2, chapter 7, the cottagers’ (De Lacey, Felix, Agatha, and Safie) sad history is revealed to Frankenstein’s creature. In an act of sincere human compassion, Felix risks his own life to deliver (jail break) a Turk who has been unjustly sentenced to death for no greater reason than his unpopular religion or false god. The Turk, promising his daughter (Safie) to his deliverer (Felix), takes the first opportunity of his newly found freedom to betray his promise and withdraw Safie from Felix! The reason for the betrayal and broken engagement of the lovers? The Turk could not bear to think of his Muslim daughter married to a non-Muslim, even if it was the same man who delivered him. Thus, Felix’s humanitarian act, inspired by compassion and without any regard for religion or the god behind it, was rewarded with evil by the one who believed in God and allowed his religion to divide, betray, and hurt the good, innocent, and those who were revealed as “society’s benefactors.” In Shelley’s hands, the creature learns that those who trust in God cannot be trusted in human relationships! Atheism’s agenda once again is subtly inserted to draw the reader away from faith and is thrown toward human reason, unaided by the need of a god or Holy Spirit.

And now to reveal one of the most curious events linking the life of Percy Bysshe Shelley to the characters and events in Frankenstein, Shelley's encounter with the devil himself! It occurred under circumstances not entirely unique for a meeting with a devil or fiend; it began on Friday, 26 February 1813. The night was dark and stormy with gale-force winds blowing in from Caernarvon Bay. Percy and his first wife Harriet were renting a home in Tan-yr-Allt, northern Wales, and for some unexplained reason that evening Percy went upstairs to bed prepared with two loaded pistols. The rest of the story is best related by Harriet in a letter written to Thomas Hookham, 12 March 1813:

Mr. S. [Shelley] promised you a recital of the horrible events that caused us to leave Wales. I have undertaken the task, as I wish to spare him, in the present nervous state of his health, every thing that can recal [sic] to his mind the horrors of that night, which I will relate. On Friday night, the 26th February, we retired to bed between ten and eleven o’clock. We had been in bed about half an hour, when Mr. S. heard a noise proceeding from one of the parlours. He immediately went down stairs with two pistols, which he had loaded that night, expecting to have occasion for them. He went into the billiard room, where he heard footsteps retreating. He followed into another little room, which was called an office. He there saw a man in the act of quitting the room through a glass window which opens into the shrubbery. The man fired at Mr. S., which he avoided. Bysshe then fired, but it flashed in the pan. The man then knocked Bysshe down, and they struggled on the ground. Bysshe then fired his second pistol, which he thought wounded him in the shoulder, as he uttered a shriek and got up, when he said these words: By God. I will be revenged! I will murder your wife. I will ravish your sister. By God I will be revenged. He then fled—as we hoped for the night. Our servants were not gone to bed, but were just going, when this horrible affair happened. This was about eleven o’clock. We all assembled in the parlour, where we remained for two hours. Mr. S. then advised us to retire, thinking it impossible he would make a second attack. We left Bysshe and our manservant, who had only arrived that day, and who knew nothing of the house, to sit up. I had been in bed three hours when I heard a pistol go off. I immediately ran downstairs, when I perceived that Bysshe’s flannel gown had been shot through, and the window curtain. Bysshe had sent Daniel to see what hour it was, when he heard a noise at the window. He went there, and a man thrust his arm through the glass and fired at him. Thank heaven! The ball went through his gown and he remained unhurt, Mr. S. happened to stand sideways; had he stood fronting, the ball must have killed him. Bysshe fired his pistol, but it would not go off. He then aimed a blow at him with an old sword which he found in the house. The assassin attempted to get the sword from him, and just as he was pulling it away Dan rushed the room, when he made his escape.19

The assassination attempt or break-in story takes a further twist with the account related the morning after the event to John Williams, Shelley’s friend. According to Williams,

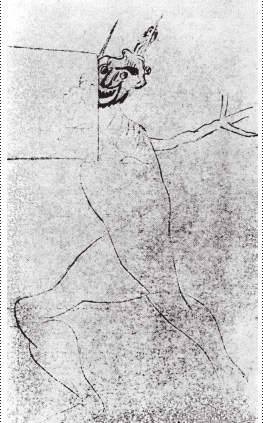

Shelley had seen a face against the window and had fired at it, shattering the glass. He had then rushed out upon the lawn, where he saw the devil leaning against a tree. As he told his story, Shelley seized pen and ink and sketched this vision upon a wooden screen and then attempted to burn the screen in order to destroy the apparition. The screen was saved with some difficulty, but was subsequently lost, not however before a copy of Shelley’s sketch was made.

SHELLEY’S JEERING-FACED

TAN-YR-ALLT DEVIL

THE SECOND COMING OF THE TAN-YR-ALLT DEVIL

If the event sounds suspiciously familiar, consider the threatening words of Frankenstein’s demonic creature on the occasion of it learning that Victor has destroyed its hopes for a mate:

Beware! Your hours will pass in dread and misery, and soon the bolt will fall which must ravish from you and your happiness for ever. Are you to be happy, while I grovel in the intensity of my wretchedness? You can blast my other passions; but revenge remains — revenge.20

And the moment of revenge as related by Victor Frankenstein:

It was eight o’clock when we landed; we walked for a short time on the shore, enjoying the transitory light, and then retired to the inn, and contemplated the lovely scene of waters, woods, and mountains, obscured in darkness, yet still displaying their black outlines.

The wind, which had fallen in the south, now rose with great violence in the west … suddenly a heavy storm of rain descended. I had been calm during the day; but so soon as night obscured the shapes of objects, a thousand fears arose in my mind. I was anxious and watchful, while my right hand grasped a pistol which was hidden in my bosom; every sound terrified me; but I resolved that I would sell my life dearly, and not relax the impeding conflict until my own life, or that of my adversary, were extinguished…

I happened to look up. The windows of the room had before been darkened; and I felt a kind of panic on seeing the pale yellow light of the moon illuminate the chamber. The shutters had been thrown back; and with a sensation of horror not to be described, I saw at the open window a figure the most hideous and abhorred. A grin was on the face of the monster; he seemed to jeer, as with his fiendish finger he pointed towards the corpse of my wife. I rushed towards the window, and drawing a pistol from my bosom, shot; but he eluded me.21

Is it just possible that the Tan-yr-Allt demon whose presence appeared suddenly at the window of a home in a remote region on a stormy evening, and then threatening vengeance against Shelley and promising to kill his wife, might have reappeared in Percy Bysshe Shelley’s autobiographical novel Frankenstein under a similar jeering form? An elusive demon, vengeful and murderous, suddenly appearing at a window on a stormy night at an inn located in a remote region intent on murdering Victor Frankenstein’s wife?

The similarities are surely monumental enough to convince even the most ardent of Mary Shelley defenders to blushingly confess that Mary undoubtedly must have—once again—taken Percy’s memories and embedded them into her ghost story. Memories which were more than a little awkward considering the fact that it was not Mary who was nestled in with Percy at Tan-yr-Allt that evening; rather the event occurred with and was recorded by his first wife Harriet, who was abandoned by Percy after he met Mary.

The conspiracy theory may slowly begin to seem quite reasonable when placed against the growing evidence that the Frankenstein story was drawn from the memories, education, and experiences of Percy Bysshe Shelley, a man who simply conspired with his then-mistress, Mary Godwin, to hide his name and later attribute the authorship to her. The demon story is one more example of how the atheist Percy Bysshe Shelley came to write the 1818 first edition of Frankenstein.

1 Percy Bysshe Shelley, The Letters of Percy Bysshe Shelley, F.L. Jones, ed., (Oxford University Press, 1964), I. No. 35, p. 35

2 Richard Holmes, Shelley: The Pursuit (E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1975), p. 46

3 Newman Ivey White, Shelley (2 Vol.) (Alfred A. Knopf, 1940), p. 113, vol. 1

4 Percy Bysshe Shelley, The Necessity of Atheism, first published anonymously in 1811 and revised in Notes to Queen Mab 1813; www.infidels.org/library/historical/percy_shelley/necessity_of_atheism.html

5 James Bieri, Percy Bysshe Shelley: A Biography (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008), p. 124. op. cit., Thomas Jefferson Hogg, The Life of Percy Bysshe Shelley, 2 volumes. (London, 1858)

6 Ibid., p. 122

7 Holmes, p. 46

8 Ibid., p. 47

9 Donald H. Reiman and Neil Fraistat, eds., Shelley’s Poetry and Prose, (W.W. Norton & Co., 2002), pp. 56–57 www.english.upenn.edu/~curran/250/mabnotes.html

10 “Zastrozzi is one of the most savage and improbable demons that ever issued from a diseased brain.” cf. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zastrozzi

11 Donald H. Reiman and Neil Fraistat, eds., Shelley’s Poetry and Prose, (W.W. Norton & Co., 2002), p. 208

12 Ibid., p. 204

13 cf. Journal of Edward Ellerker Williams, with an introduction by Richard Garnett (1902), London, Elkin Mathews

14 Charles E. Robinson, ed., Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus: The Original Two-Volume Novel of 1816–1817 from the Bodleian Library Manuscripts by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (Vintage Books, 2008), p. 25

15 Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus, J. Paul Hunter, ed., The Original 1818 Text Norton Critical Edition (W.W. Norton & Co., 1996), p. 186. Op. cit., On Frankenstein by Percy Bysshe Shelley, written in 1817; published (posthumously) in The Athenaeum Journal of Literature, Science and the Fine Arts, Nov. 10, 1832

16 Percy Bysshe Shelley, Peter Bell the Third (Composed 1819; Published 1839 in Mary Shelley’s 2nd Edition of The Collected Works of Percy Bysshe Shelley)

17 Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus, J. Paul Hunter, ed., The Original 1818 Text Norton Critical Edition (W.W. Norton & Co., 1996), p. 56

18 Richard Holmes, Shelley: The Pursuit (E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1975), pp. 191–193

19 Newman Ivey White, Shelley (2 Vol.) (Alfred A. Knopf, 1940), p. 281, vol. 1

20 Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus, J. Paul Hunter, ed., The Original 1818 Text Norton Critical Edition (W.W. Norton & Co., 1996), p. 116

21 Ibid., p. 136