It is well understood that the final word concerning the authorship of Frankenstein has not yet been written. In one regard, this is simply among the first modern words to challenge the subject of the true author behind Frankenstein. As proven earlier, the first readers and critics of Frankenstein, including none less than Sir Walter Scott, challenged the idea that this was a novel penned by Mary Shelley. Like the sea-tossed body of Percy Shelley, time eroded and concealed the finest details which were trademark signs of Percy Bysshe Shelley until all that was left was the Mary Shelley waking-nightmare story which became as famous as the novel itself. In a fashion perhaps most appreciated by a character larger than life, like Percy Shelley, this book has attempted to pull back the Illuminati curtain and test for literary DNA in the once anonymously written Frankenstein of 1818.

The evidence presented is not exhaustive but merely a starting point of comparison between the life experiences, education, methods, writings, and social/political agenda linking Percy Bysshe Shelley to the novel Frankenstein. It has been shown that the introductory Prefaces differ widely between 1818 and 1831, a fact that suggests duplicity or conspiracy; the possibility that the same author could so easily mistake historic events in the writing of the novel, or worse yet dismiss the contribution of a key person associated with the book, is beyond credibility to any reasonable person. If, as history now records, Mary Shelley was the author, it is an outright lie that she did not owe a single suggestion to her husband Percy Bysshe Shelley in the writing of the book. The internal inconsistencies are proof enough: Mary’s supposed overhearing of a conversation about Erasmus Darwin and German physiological writers contradicts her own statement concerning Percy’s lack of suggestion toward the novel. Furthermore, it strains the imagination to believe that Mary had forgotten in less than fifteen years that her husband had (at the minimum) edited the book and had made no fewer than 4,000–5,000 changes, according to Charles Robinson’s handwriting analysis of the Frankenstein notebooks. If Mary Shelley had written the first edition of Frankenstein, one would be obligated to fault her with the worst form of betrayal by excluding Percy Bysshe Shelley’s contribution to Frankenstein. Thus the question must be raised: how is it that Percy Shelley has been so quickly dismissed while so deeply involved in the writing of Frankenstein? Either the integrity of Mary Shelley must be tarred with the darkest of deceitful brushes, or an explanation must be supplied for her apparent desire to erase all memory of her husband from the history of her first novel. This book, rather than impugn the character of Mary Shelley, celebrates her as a co-conspirator in the anonymously written first edition of Frankenstein which was in fact authored by Percy Bysshe Shelley.

But what of the Frankenstein Notebooks with Mary’s recognizable pen strokes throughout? What of the approximately 70,000 words that were written in her hand? The burden of evidence on this point alone has seemingly closed the case against Percy Bysshe Shelley… and yet, as Donald H. Reiman and Neil Fraistat observe in the Norton Critical Edition of Shelley’s Poetry and Prose,

Mary Shelley transcribed for the press most or all of Acts I–III [Prometheus Unbound] between September 5 and 12, 1819, and all of Act IV in mid-December 1819. As was his [Percy Bysshe Shelley's] usual practice, Shelley appears to have corrected the press transcripts, making a series of small final revisions to prepare the poem.1

The method by which Percy Bysshe Shelley wrote most of his poems and prose was by means of an amanuensis. Shelley’s nearly illegible handwriting required the use of a near companion, most often his wife Mary Shelley, to prepare his writing for publication as well as to write down his poems or stories as he dictated. His “usual practice” was to make final corrections to his work but not necessarily to be the one in whose hand his works were initially or finally written. Thus, the handwriting analysis determination of authorship fails to be convincing evidence that Mary Shelley was the author of Frankenstein but rather suggests that the scholars have only identified who held the pen, not who the author was. It is a simple mistake to make, but the consequences of placing all of the authorship eggs in this handwriting basket is problematic and misleading, to say the least.

Another interesting and often overlooked fact that was raised in this study concerned Percy Bysshe Shelley’s penchant for writing under pseudonyms or, preferably, in an anonymous fashion. Few readers of Frankenstein today would be aware that the first edition of the book was published anonymously, as even the first editions on today’s bookshelves are crowned with the author’s name, Mary Shelley; this is clearly not how the book first appeared in 1818. The fact that Frankenstein was published anonymously is less mysterious in light of the fact that it was a virtual signature of Percy Bysshe Shelley to write and publish without his name appearing in the book. His agenda was neither fame nor fortune, but rather to be a revolutionary, and to accomplish his agenda he used anonymous poems, essays, letters in bottles, letters attached to kites, and fictional stories to spread his dangerous ideas. When critics pointed the finger to Shelley after Frankenstein was published, it is not surprising that he dodged the recognition and passed the story off as a juvenile attempt by a young woman who was doing nothing more harmful than writing a mere ghost story.

The revolutionary tone of Frankenstein was also considered from several perspectives, including Shelley’s atheism. The obvious removal of a divine Creator, who was replaced by an alchemist-scientist using the laws of Nature to give life, stands in direct opposition to all that the Christian faith advocates. The story behind Frankenstein is more suggestive of a changing world where modern science and ancient alchemy were suitable, perhaps far better, authorities to rely on in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Few writers of that period were more acquainted with the study of alchemy and modern science than Percy Bysshe Shelley, a man trained by some of the best scholars of the day, including Dr. James Lind. The subtle undermining of confidence in the Church reached climactic force as an innocent woman, Justine, confesses to a crime which she did not commit, simply for the sake of obtaining the promise of heaven from an obstinate priest demanding a confession from her. Who better than an atheistic Shelley could remove the necessity of God the Creator from mankind and replace God with science, while at the same moment lay explosives at the doorstep of St. Peter’s Church? This revolutionary idea found its way into what was perceived as a mere ghost story and it fit the pattern of Shelley’s revolution, which was nothing less than to tear down the Christian faith.

Another of Shelley’s characteristic revolutionary ideas was his intellectual association to the Bavarian Illuminati platform as advocated by Adam Weishaupt. An avid follower of Weishaupt, Shelley was known to travel with copies of his Illuminati doctrine and to share them with his closest friends. The chosen city for the birth of the new creature was none other than Ingolstadt, the university city where Weishaupt taught and where the Bavarian Illuminati was birthed. A new man of science and alchemy for a new world order, so was Shelley’s message hidden carefully in Frankenstein. Although science was ready for the new man, and the philosophy for the new world was bursting at the seams, it was clear to Shelley that the world was not ready for such a man. Like the Ingolstadt creature and the scientist who fashioned him, Percy Bysshe Shelley was front and center on the stage of this changing world but found that his ideas were unwanted, just as he was unwanted. Frankenstein is in some degree Shelley’s critique of the superstition of the old world still dominating the leaders and people of the emerging new world.

Finally, it was revealed that Shelley’s philosophy of love had much to do with his own sense of being an outcast in the world, searching for his other half—a theme he managed to run throughout the Frankenstein story, and a theme he repeated in his poems and early novels. The philosophy for such a perfect, though difficult to find, love was explicitly detailed in Plato’s work The Symposium, which Shelley was busy translating at the moment that Frankenstein was first published. Adding commentary to his fictional autobiography, Shelley completed the circle of writings about love’s true nature in his essay On Love, written immediately after the completion of his translation of Plato’s Symposium. Shelley, as the Sensitive Plant, the lone and unbeautiful hermaphroditic plant in the garden, longed for his own companion who would complement him, but found that this world had no such person for him—the very plight which drove Walton, Frankenstein, and the creature in Shelley’s novel.

It has been repeatedly suggested that Frankenstein is a fictional autobiography by Percy Bysshe Shelley, based on that which he felt and knew most perfectly, his own life and worldview. To read Frankenstein as the product of Mary Shelley is to imagine that she, in her short acquaintance with Percy, not only understood his deepest inner thoughts but also had somehow gathered his memories and education and used them to write her own biography of Percy without his notice or objection. To miss the biographical details relating the life of Percy Bysshe Shelley to the primary characters in Frankenstein is to read the book with one eye closed and the other eye intentionally avoiding contact with the life and philosophy of Percy Bysshe Shelley.

One might ask whether the question of Frankenstein’s author makes any difference today. What agenda is behind this book, after all? As previously stated, this book does not seek to malign the name of Mary Shelley in the least; in fact, it offers an explanation for what would otherwise require a complete reassessment of her integrity. Neither does this book seek to toss aside all previous studies and scholarly works on Frankenstein; each contribution to this timeless novel sheds further light on the complexity of Shelley’s work. So, once again, why does it matter who wrote Frankenstein?

What matters most is that the very same issues which gave birth to this novel are presented to us still today: the search for the elusive soul mate; questions about the role of science and healing, regeneration, conception, and particularly the blending of technology and human nature—the Transhumanist movement. Is man a creation of God, or is mankind a mere rat in the scientific laboratory where digital implants, DNA manipulation, and the Philosopher’s Stone are still up for grabs by the highest corporate bidders? Is there a middle ground for science to bring all of its gifts to benefit mankind while leaving human nature safely and purely human? Are we on the brink of a new civilization, and will it produce a new race of elites or slaves engineered for the exploitation of elites? Essentially, the questions raised by Percy Bysshe Shelley still matter because as Frankenstein’s author, Shelley was a man of science, a man questioning the authority structures of government and the church, the usefulness of peaceful revolutions to reclaim human freedom, and the challenges that face each individual who walks through this life wondering if there is “just that perfect someone,” a “soul mate” who would complete all of the unfulfilled longings that every human hopes to overcome with “love.”

To relegate Frankenstein’s authorship to anyone other than Percy Bysshe Shelley is to miss the underlying human conflict and hope for love in a world where men and women are equally free to believe as they choose, love whomever they find as their “other half,” and to be truly free of oppression whether it comes in the form of government or religion. Mary Shelley’s iconic name as the author of Frankenstein has become the accidental detour away from the issues that drove this novel to be written in the first place, a detour sign well positioned by Percy Bysshe Shelley because he was aware that the world of 1818 was not quite ready to tackle these issues. To answer the question “does it matter?” the answer must be YES! This is the moment to begin addressing Shelley’s dilemma, and what better place to begin raising the question than in the schools where Frankenstein is still read: by high school students preparing for college; in colleges where students are preparing for their role in the world as the next generation of leaders. As a former college professor and as a high school teacher today, I can confirm that Frankenstein, particularly the 1818 edition, presents every opportunity to explore the history of alchemy, the role of science, the social structures of morality and human rights, enlightenment doctrines, justifiable revolutions, the authority of government and various religions, and of course the beauty of English literature in the hands of one of England’s finest poets and authors, Percy Bysshe Shelley. Yes, authorship matters.

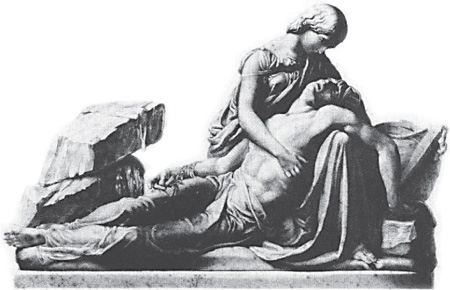

ENGRAVING BY GEORGE J. STODART, AFTER A MONUMENT BY HENRY WEEKES (1807–1877)

MONUMENT DEPICTING MARY AND PERCY SHELLEY ON THE OCCASION OF HIS DEATH BY DROWNING. NOTE THE PIETÀ-LIKE SIMILARITIES LINKING MARY SHELLEY’S IMPLIED SAINTLY AND SUFFERING QUALITIES TO THE VIRGIN MARY. ONE MUST WONDER IF PERCY COULD EVER IMAGINE BEING IN SUCH A POSE RESEMBLING THE CHRISTIAN SON OF GOD.

1 Donald H. Reiman and Neil Fraistat, eds., Norton Critical Edition Shelley’s Poetry and Prose (W.W. Norton & Co., 2002), p. 208