Society

ROCHESTER retained the economic functions and much of the look and feel of a country town. But market operations that stabilized the business community in the 1820s filled the streets and workshops with the fastest-growing population in the United States. Many were transients on their way farther west. But most lived and worked in Rochester, creating a bottom-heavy and unstable urban population. In 1827 only 21 percent of adult male Rochesterians were independent proprietors. The others worked for them. Twenty-six percent of the work force possessed no particular skill and looked for casual work along the canal, around the mills and loading docks, and in the streets. But by far the largest group -45 percent—was made up of the journeyman craftsmen who built the town and filled its bulging workshops.1 In 1830 three-fourths of the population was under thirty years of age. And in the prime working ages of twenty through fifty, the population was overwhelmingly male, suggesting that accounts which described Rochester workmen as young, unattached drifters were not far from accurate.2 Perhaps most unsettling, these men moved too fast to be counted. In 1826 an editor estimated that 120 persons left Rochester every day, while 130 more arrived to take their places. Of the hundreds of wage earners living in Rochester in 1827, fewer than one in six would stay as long as six years.3 Near the bottom, the population of Rochester changed constantly.

Few American communities—certainly none in which

Rochester businessmen had lived—had ever held such a young, unstable, and poor population. Day laborers and journeyman craftsmen made up 71 percent of the adult male work force. In Philadelphia, as late as 1820, the comparable figure was 39 percent.4 Rochester may have looked like a country town. But underneath, it was a blue-collar city. When Charles Finney arrived late in 1830, he found merchants and master workmen at the top of a city that they owned but could not control. The following pages trace their loss of dominance into three closely related spheres: the organization of work, relations between work and family life, and the changing spatial organization of the town.

The loss of social control began, paradoxically, with the imposition of new and tighter controls over the process of labor. For while market operations revolutionized the scale and intensity of work, they freed wage earners from the immediate discipline exerted by older, household-centered relations of production. Shoe factories, cooperages, and building crews are among the operations for which that process can be documented in some detail. Briefly, here is what happened to the organization of work in those trades.

We begin with shoemaking, one of the key links in Rochester’s relations with the countryside. Hides came down the Genesee and were tanned and fabricated into shoes for sale back to the farmers. The earliest shops were small and concentrated on custom work. But within a few years shoemakers were serving a broad regional market. In 1821 a master shoemaker boasted that he was “constantly adding to the number of his workmen” and that he could satisfy not only retail customers but “any store in the state, west of Albany.”5 The 1827 directory listed 111 journeyman shoemakers, most of whom seem to have worked in a few large establishments.

Jesse Hatch counted nine shops that combined shoemaking and retailing in 1831, and left a description of the one in which he found work:

It was customary for the boss, with the younger apprentices, to occupy the room in front where, with bared arms and leather aprons, they performed their work and met their customers. A shop in the rear or above would be occupied by the tramping journeyman and the older apprentice … The shops were low rooms in which from fifteen to twenty men worked …6

In the earliest shops, masters had hired few helpers. Shoemaking and retailing were performed in the same room and by the same men. But Hatch’s employer dealt personally only with his customers and with a few of his younger employees, and it is doubtful that he spent much time making shoes. The front and back rooms had become very different kinds of space.

A newer form, which came to dominate the trade in the late 1820s and early 1830s, completed the separation of men who made shoes from those who sold them. Now masters kept only a foreman and a few trusted employees in the shop. These fitted customers, rough-cut the uppers, and sent them by runner to shoemakers’ boardinghouses that dotted back streets in the downtown area. There journeymen shaped and finished the parts. Runners took these to the homes of women who sewed shoes together, then brought the finished product back to the store. The timing of this change is unclear, and certainly it varied from shop to shop. Hatch remembered that in 1831 “most of the work” was done in boardinghouses.7 In 1834 Rachel Gibson worked as a shoe binder on Mechanic Street. Three doors down lived James Piersons, a runner. Neither occupation was represented in the directory published seven years earlier. At the same time, the proportion of journeymen who lived in boardinghouses doubled. By the early 1830s the business of selling shoes was separate from the act of making

them. Control over the trade fell from shoemakers to the merchant capitalists (many of them former shoemakers), who arranged the purchase of raw materials, organized the cheap and rapid production of shoes, and marketed the finished product.

The separation of proprietor from wage earner took place more quickly among coopers. Coopers’ shops were ancillary to flour mills that used hundreds of thousands of barrels annually. The two largest shops were owned by the millers Matthew Brown and Harvey Ely, and operated as parts of their mills. Steady markets and high profits encouraged other businessmen to invest in cooperages. The realtors Bradford and Moses King and the publisher Luther Tucker were among those who went into the business of making barrels.8 And of the shop owners listed as coopers, some spent their time doing other things. The directory described Pierce Darrow as a cooper. One of the larger proprietors, he called himself a lumber merchant.9 Probably it was a better description of what he did. Flour barrels were produced in huge quantities, and they did not have to be as tight and well made as kegs and barrels that held liquid. Coopers did little more than assemble staves that were pre-cut up the valley. A skilled craft had become linked with extensive and unified business operations, and there was little employment in Rochester for men who knew how to make fine barrels. It is noteworthy that this was one of the few skilled trades that employed significant numbers of blacks—men who with few exceptions concentrated in the least desirable kinds of work.10

By far the largest group of Rochester workingmen was engaged in building the town itself. Rochester was the fastest-growing city in the United States, and carpenters seldom contracted for individual houses as they had in older and more slowly growing communities. The need for housing produced a uniform two-story, four-room house (whitewashed and trimmed in dark green) that was duplicated endlessly across the landscape. During the building season of 1827, Rochester

builders put up 352 new houses.11 That was about one and a half houses per carpenter in the space of a few months. An editor marveled at the number of “frames” being raised, suggesting that these were cheap and easily constructed balloon-frame houses, put up quickly by large groups of men. They did not have to custom-fit doors and window frames, for Silas Hawley—with the help of two sons, three journeymen, and a roomful of water-driven machinery—turned out thousands of them in uniform sizes.12 Building crews worked in gangs supervised by foremen and subcontractors, and the men who organized the operation and sold the finished houses were as often as not land speculators. Nathaniel Rochester, for instance, built and owned scores of houses all over town. So did others whose occupations were listed as merchant, miller, realtor—even shoemaker.13 Like coopers and shoemakers, Rochester building tradesmen worked for men they seldom saw.

These three trades were controlled by merchant capitalists, men more skilled at organizing and driving workers and selling what they made than at making things themselves.14 In each trade the result was a dilution of traditional skills, an expansion in the size of work groups, and the making of a lot of money by men who controlled the operation. There were similar developments among metal workers, tailors, hatters, clothiers, and boat builders.15 Many other crafts that did not come under the direct control of merchant capitalists were ancillary to their operations. Lastmakers and pegmakers were subsidiary to the shoe trade. Brickmakers, paint mixers, and nailers produced for master builders. In most manufacturing operations, the greatest rewards went to masters who turned themselves into businessmen—or to men who had never been masters at all.

While most wage earners came under the ultimate control of merchant capitalists, changes in the pace, scale, and organization of work varied enormously from trade to trade. Some coopers escaped change altogether. The smallest shops were

owned by Irishmen who refused to alter the customs of their trade, and throughout the 1820s and 1830s, coopers in the fifth-ward neighborhood known as Dublin spent Sundays drunk and Mondays visiting their friends, sharpening their tools, and clearing their heads. From Tuesday on, they worked relentlessly to deliver barrels to the mills on time.16 (No doubt coopers directly attached to the mills experienced more regular and more harassing forms of discipline.) Shoemakers in the boardinghouses were also free to work in spurts and at irregular times—again, as long as they met insistent deadlines. Shoemaking was quiet and sedentary, and the men read aloud, gambled, told stories, and debated endlessly.17 Carpenters had the worst of it. They labored from sunrise to sunset under the eyes of men who contracted to build scores of houses over a short season, and the work was unremitting. Unable to control their conditions of work or to mix work and leisure, they organized to limit the time that they spent on the job. In 1834 journeyman carpenters struck for a ten-hour day, and announced wearily that “we will be faithful to our employers during the ten hours and no longer.”18

But while circumstances varied, journeymen all over the city experienced harsher, more impersonal, and more transparent forms of exploitation than had men in the same trades a few years earlier. At the same time they were freed from controls imposed by the smaller workshops, for the businessmen who bought and controlled their labor were seldom present when the work was performed. They worked together and talked and joked among themselves, and they forged sensibilities that were specific to the class of wage-earning craftsmen. Basic to that mental set was the proposition that master and wage earner were different and opposed kinds of men. In 1829 an editor had occasion to use the word boss, and followed it with an asterisk. “A foreman or master workman,” he explained. “Of modern coinage, we believe.”19 Five years later the striking carpenters used the word again. This time, there was no asterisk.20

The reorganization of work brought change into the most intimate corners of daily life. For until the coming of merchant capitalism, most Rochester wage earners lived with their employers and shared in their private lives. Evidence is fragmentary and incomplete, and quantifiable data are unavailable, but this much is clear: in 1820 merchants and master workmen lived above, behind, or very near their places of business, and employees boarded in their homes. On most jobs, employment was conditional on co-residence. Even workmen whose fathers and brothers headed households in Rochester lived with employers.21 Work, leisure, and domestic life were acted out in the same place and by the same people, and relations between masters and men transferred without a break from the workshop to the fireside.

In traditional usage the word family, with all that it implied, stretched to include co-resident employees. When the publisher Everard Peck married in 1820, his wife spent weeks setting up a new household, then wrote home: “We collected our family together which consists of seven persons and we think ourselves pleasantly situated.”22 How newlyweds—both of them marrying for the first time—had gathered such a large family must remain a mystery. But some of those seven almost certainly worked for Everard Peck. (In 1827 the Peck household included Everard and his wife and children, his brother and business partner Jesse, a day laborer, and four journeyman printers and bookbinders.) Peck took these men into his home knowing that he owed them more than room and board. He assured his father-in-law that

We cannot be too frequently or too forcibly reminded of the responsibility under which we are placed, to discharge faithfully the important trust committed to our charge. Although we are conscious that we fall short of discharging our duty to each other and to those who are placed in our family and under our care we have not been we hope altogether unmindful of it.

Our own happiness, the welfare of those connected with us, and the harmony and good order of our family, doubtless depend very much on the manner in which we commence our new course in life.23

Puritan family government was in decay, but it still ranked high in Rochester Protestants’ ideas of where authority was located and how it should be exercised. Wage earners were young and poor and numerous. Left alone, they might cause trouble. But with each of them a member of some household, and with householders answerable for the behavior of everyone under their care, the community could breathe easy.24 Public opinion held heads of families accountable for what their “children and dependents” did. So did New York law, and a justice of the peace threatened to take legal action when he spied a group of boys and young men skating on Sunday, “to the great shame and disgrace of their parents and masters.” 25 For those who attended Presbyterian and Baptist churches, religious sanctions reinforced custom, law, and watchful neighbors. The covenant at First Presbyterian Church reminded householders that they were “under solemn obligations to restrain their children and dependents … from all sinful and unlawful amusements,” and to enforce their attendance at church. The rules of practice at Second Church, drawn up at the height of the boom in 1825, repeated those admonitions.26 A year later Robert Willson, the town’s wealthiest master builder, shared his house with five journeyman carpenters and, according to one of his neighbors, “took an interest in the conduct of all the young men he employed.”27 As late as 1828, a businessman reaffirmed the belief that “every habitual sin openly practised in the family, by any of its members, is justly chargeable upon its head.” (He gave this as one of his reasons for denying drinks to his workmen. The result was that “their work has been better done, and my family more quiet and orderly.”)28 The tradition that a man’s responsibility

for the welfare and behavior of his wife and children extended to whoever else slept beneath his roof came to Rochester with the first settlers. If we may believe these pious men, it remained strong for many years.

But even as merchants and masters talked of patriarchy, the intimacy on which it depended fell apart. Everard Peck was co-publisher of a small weekly newspaper when he established his household in 1820. By 1830 he operated printing offices and a daily paper, a bookstore, a paper mill and warehouse, and speculated extensively in Rochester real estate. While he continued to board employees, his attention was engaged in operations that went beyond relations with young printers and bookbinders. The same subtle estrangement was occurring in stores and workshops all over Rochester. And in more and more cases, the change was not so subtle: workmen were leaving the homes of their employers.

The first opportunity to view that process comes with the Rochester Directory of 1827. That document lists the names, residences, and occupations of males over the age of sixteen. Boarders appear beside their landlords, permitting a reconstruction of the adult male membership of households in 1827. The figures are incomplete, for they exclude women and children. Domestic servants and the younger apprentices and clerks are lost from view, and there were many of these. Simeon Allcott’s cotton factory and the tannery operated by Samuel Works and Jacob Graves hired large numbers of children. (Both expressed regrets when young workers were sucked into their machinery and killed.29) Work crews in the larger shoe shops included four or five apprentices, and there are enough advertisements for apprentices, notices of runaways, and wringing of hands over the moral state of apprentices and clerks to suggest that children participated in most economic operations. Servant girls, apprentices, and clerks lived where they worked. Figures that exclude them seriously underestimate the number of wage earners living with their

employers. But the households of Rochester proprietors were crowded nonetheless.

Fifty-two percent of master craftsmen and 39 percent of merchants and professionals included adult male wage earners in their households in 1827. But these bulging families housed only a small proportion of Rochester workingmen. The large number of lodgers—overwhelmingly wage earners—in households headed by laborers and journeymen points to that fact. So does the prevalence of boarders in the homes of shopkeepers and petty proprietors, many of whom were grocers who rented beds to workmen.30 In all, 37 percent of journeymen headed their own households. Twenty-nine percent of the others boarded with them. Another 11 percent slept in boardinghouses and groceries, leaving only 22 percent in households headed by employers.31 The custom of providing room and board as part of a workman’s wages was alive in 1827. But it certainly was in decay.

Proprietors in 1827 were in transit between family-centered work relations and pure wage labor. A second directory appeared in 1834. Reliable lists of masters in that year can be compiled only for shoemakers and proprietors of a variety of small indoor workshops, and in some ways that is a happy limitation. Merchant capitalists were in firm control of the shoe trade by 1834, and the organization of work among shoemakers changed dramatically. The shops averaged nine journeymen, and sometimes had more than twenty. But among tinsmiths, sashmakers, gunsmiths, printers, and the like, work groups remained small. In many cases the master still worked beside his employees. Thus these two groups represent extremes in the development of Rochester manufactures. In 1827 only one in four shoemakers but almost half the small-shop craftsmen lived with proprietors in their trades. Living arrangements for both groups, however, headed in the same direction. By 1834 the figure for live-in shoemakers had dropped to one in twenty; for small-shop craftsmen to one in

three.32 Even wage earners who continued to receive room and board from their employers sometimes received it in peculiar ways. A young man who clerked in a downtown dry-goods store in 1828 remembered sleeping on a cot in the back room, surrounded by barrels and packing crates. His employer, assured that the store was being watched at night, slept with his family on a quiet side street.33

Rochester merchants and masters had grown up in communities in which labor relations and family life were structurally and emotionally inseparable. Most had served resident clerkships and apprenticeships, some of them in Rochester itself.34 But in the 1820s the nature of work and of the work force made it difficult to provide employees with food, lodgings, behavioral models. and domestic discipline. Even proprietors who kept employees in their homes (and these tended more and more to be the youngest apprentices and clerks) often retained customary forms while neglecting the responsibilities that had given them meaning. An editor addressed these questions to the town’s churchgoing businessmen:

Have apprentices and clerks immortal souls? Are their masters, or employers, being professed Christians, to be considered as having charge of those souls? Is prayer, and especially family prayer, one of the means of grace? Are those masters or employers, being professors of religion, doing their duty, who keep their apprentices or clerks in the shop, or store, during the time of family worship, when those apprentices and clerks reside in, and are members of the family? These apprentices and clerks, being excluded from family prayer, is there not reason to fear they are also forgotten in secret devotion? May not these questions furnish one reason why there are so many ungodly clerks and apprentices in our country?35

Certainly Rochester had its share of ungodly young employees. And men who had abdicated immediate, personal

responsibility for their spiritual state could blame no one but themselves.

In 1820 most Rochesterians worked, played, and slept in the same place. There were no neighborhoods as we understand them: no distinct commercial and residential zones, no residential areas based upon social class. The integration of work and family life and of master and wage earner produced a nearly random mix of people and activities on the city’s streets. That changed quickly after 1825. Masters moved their families away from their places of business, and some of the side streets took on a distinctive middle-class, residential character. Workingmen, freed from their employers’ households, moved into neighborhoods of their own. Within a few short years, the transformation of work and the estrangement of master from wage earner were recapitulated in the social geography of Rochester.

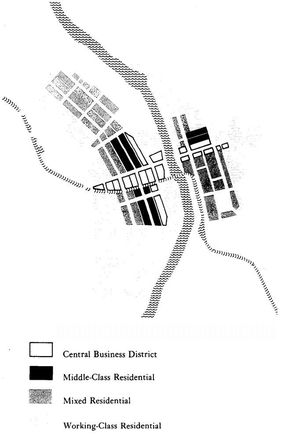

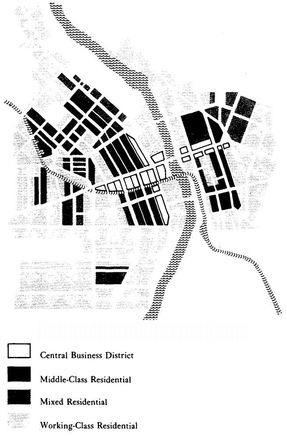

Maps 1 and 2 trace that development between 1827 and 1834. On those maps, the streets that formed the Four Corners (Buffalo, Main, State, and Exchange) are termed the central business district. This included nearly all stores and offices and most of the larger workshops that were not powered by water.36 Other streets are classified by the proportions of wage earners and proprietors who lived on them, computed from samples that include all businessmen, professionals, and master workmen, all day laborers, and all journeyman shoemakers and small-shop craftsmen—exclusive of those who boarded with their employers. This population includes roughly equal numbers of Rochester’s richest and poorest men. Streets on which proprietors accounted for 70 percent or more of sample residents are termed middle-class residential. Those with between 30 and 69 percent proprietors are mixed residential, and those with fewer than 30 percent proprietors are working-class residential. All but a few streets ended or changed names within two blocks. Thus these figures map the demography of social class block by block; it is a map that changed dramatically between 1827 and 1834.37

Map 1. ROCHESTER NEIGHBORHOODS IN 1827

Map 2. ROCHESTER NEIGHBORHOODS IN 1834

In 1827 the English traveler Basil Hall sat at his window in the Eagle Tavern and sketched the buildings running east from the courthouse square on Buffalo Street. They included a cabinet factory, a grocery, a painter’s shop, a provisions store, and a shoe factory. Each of them was a modest, two-story wooden structure, and each had what appears to have been living space on the second floor.38 Masters and merchants used those rooms. Fully 37 percent of business-owning families resided—presumably at or near their places of business—on the busiest downtown streets. So did 31 percent of journeymen and laborers. The town’s central intersection remained mixed commercial, manufacturing, residential, and recreational space.

The side streets on which the remaining two-thirds of Rochesterians lived were as thoroughly mixed as the Four Corners. Residents of even the wealthiest blocks walked out of their houses to find a cross section of the city. Deacon Oren Sage of the Baptist Church, for instance, owned a house at the corner of Fitzhugh and Ann. In the mornings he walked down the most uniformly wealthy street in Rochester. But tucked between the homes of merchants and manufacturers were four households headed by day laborers, two headed by journeyman shoemakers, another headed by a printer, and two workingmen’s boardinghouses. Along with these came a variety of nonresidential establishments. The Quaker Meetinghouse was across the street from Sage’s home, and sprinkled down the block were a bakery owned by a family of former slaves, a combined tailor’s shop and neighborhood bar, Brick Presbyterian Church, a livery stable with a carriage factory upstairs, and the Monroe County Jail.39 Deacon Sage stepped from

North Fitzhugh onto Buffalo Street and found only a noisier and more crowded part of the remarkably undifferentiated space in which he worked and made his home.

We cannot, however, view neighborhoods at only one point in time, for the integration of social classes and of economic and domestic activities was breaking down in the late 1820s. The change was dramatized in 1828 with the opening of Reynolds Arcade on Buffalo Street. That building provided four stories of office space to businessmen and professionals, all of whom lived someplace else. Across the river the Globe Building rented water-powered workrooms to at least fifteen manufacturers—again, without living space. By 1834 Buffalo and Main and the major artery that crossed them west of the river presented a continuous line of brick store fronts. The business district stood nearly empty at night: only 15 percent of proprietors continued to live on those streets. Masters had separated their families from their work, and there is evidence that the change was bound up with a new concern for privacy. Even men who still lived and worked in the same place found ways to create distinct domestic territory. Many lawyers, for instance, kept offices in their homes. In 1834 they announced that they did not wish to be bothered before nine in the morning or after five in the evening. While it remained convenient to combine economic and family space, they had apparently determined to separate economic from domestic time.40

Business-owning families were in retreat from the world of work, and from the increasingly distinct world of workingmen. By 1834 the middle class concentrated off Buffalo in the first and third wards and on North St. Paul and Clinton Streets on the east side. Workingmen disappeared from those streets. On South Fitzhugh the number of wage earners dropped from five to none; on North Sophia from twenty to six; on South Clinton from nine to two; on North Fitzhugh from seven to two (the boardinghouses, the bakery, the tailor’s shop and bar, and the county jail had also disappeared). Workmen

still clustered near the center of town—on Mechanic and Water Streets, in the mixed manufacturing and residential jumble of South St. Paul, and in alleys throughout the downtown area. But they dispersed more and more toward the outskirts: in Dublin, in the Cornhill section of the third ward, and in the tangle of little streets that filled the second ward and sprawled north beyond the city limits. It was the classic spatial pattern of nineteenth-century cities.41

By 1834 the social geography of Rochester was class-specific: master and wage earner no longer lived in the same households or on the same blocks. But except at the outskirts, no class could claim regions of the city as its own. Nearly every family still lived within 750 yards of the Four Corners, and residents of the most exclusive streets could look across their back fences or around the corner and see the new working-class neighborhoods. And every night the sounds of quarrels, shouting, and laughter from the poorer quarters invaded their newly secluded domestic worlds. North St. Paul, for instance, had become an exclusively middle-class enclave on the east side. A few steps toward the river stood Water and Mechanic Streets, a jumble of shacks and cheap rooming houses that made up one of the poorest, noisiest, and most congested areas of Rochester. Towering over this slum, within easy smelling distance of the fine houses on St. Paul, stood one of the largest tanneries in the United States. To the north sprawled Dublin. St. Paul was the only path from there to the downtown jobs and amusements. One wealthy resident remembered coming out of his house on Sunday morning and finding a drunk asleep on the porch.42

Across the river, South Fitzhugh Street was now a double row of mansions running off the courthouse square. We may be certain that few of the families on Fitzhugh joined the crowds at the circus on Exchange Street. But they heard clapping and shouting whenever that building was open. Three blocks west of them a fire on Ford Street was attributed to the

drunkenness of everyone in the house, while on Troup Street, within easy earshot of Fitzhugh, a gathering of workmen and their families broke into a fight in which a man was stabbed and a woman who ran in to stop it was hit on the breast and bitten badly on the finger.43 In 1829 Edward Morgan went to jail for operating a gambling room in his house on South Sophia, only a few steps away from the families on Fitzhugh.44 Grocers on nearby streets were frequently hauled into court for opening their doors and allowing men to drink and make noise on Sunday. Finally, the Erie Canal crossed the northern end of the block. The principal boat basin stood across Exchange, and boats waiting to unload lined the canal as it crossed Fitzhugh. A brawl between rival crews that began at the basin and spilled onto the Four Corners in 1829 was certainly heard if not seen by the people on South Fitzhugh.45 So were the transgressions of one Erastus Bearcup, a steersman arrested in 1826 for shouting obscenities at ladies on a passing boat.46

Across Buffalo, comfortable residents of the first ward and boarders at the prestigious Eagle Tavern contended not only with the poor neighborhoods that surrounded them but with the theater on State Street. Theater crowds were rowdy. During a performance of Otbello, the manager had to stop the show and plead with the audience to stop shouting and throwing things at the actors. A sleepless editor complained that

the inhabitants who are so unfortunate as to reside within gunshot of the theatre, have been compelled to hear till midnight or after, reiterated peals of booting, bowling, shouting, shrieking, and almost every other unseemly noise, that it is possible for the human gullet to send forth, insomuch that it is next to impossible to obtain repose till the theatrical audience have retired to their homes or hovels.47

And so on. Businessmen and their families worried incessantly about what went on in the squalid streets and questionable establishments that surrounded their homes. Perhaps the fact that they could hear transgressions but not see them added a touch of menace to what they perceived.

By 1830 the household economy had all but passed out of existence, and so had the social order that it sustained. Work, family life, the makeup of neighborhoods—the whole pattern of society—separated class from class: master and wage earner inhabited distinct social worlds. Workmen experienced new kinds of harassment on the job. But after work they entered a fraternal, neighborhood-based society in which they were free to do what they wanted. At the same time masters devised standards of work discipline, domestic privacy, and social peace that were directly antithetical to the spontaneous and noisy sociability of the workingmen. The two worlds stood within a few yards of each other, and they fought constantly. That battle took place on many fronts. But from the beginning it centered on alcohol.

The temperance question was nonexistent in 1825. Three years later it was a middle-class obsession.48 Sullen and disrespectful employees, runaway husbands, paupers, Sabbath breakers, brawlers, theatergoers: middle-class minds joined them in the image of a drink-crazed proletariat. In 1829 the county grand jury repeated what had become, in a remarkably short time, bourgeois knowledge: strong drink was “the cause of almost all of the crime and almost all of the misery that flesh is heir to.”49

These sentiments were new in the late 1820s. Whiskey was not, and we must ask how liquor became a problem, and particularly how it came to shape perceptions of every other social ill. That search will take us back into workshops,

households, and neighborhoods. For working-class drinking and middle-class anxieties about it were bound up with the economic and social transformation of the 1820s. Liquor was indeed a fitting symbol of what had happened: nowhere was the making of distinct classes and the collapse of old social controls dramatized more neatly, more angrily, and in so many aspects of life.

Most temperance advocates had been drinking all their lives, for until the middle 1820s liquor was an absolutely normal accompaniment to whatever men did in groups. Nearly every family kept a bottle in the house to “treat” their guests and workmen, and such community gatherings as election days, militia musters, and Fourth of July celebrations invariably witnessed heavy drinking by men at all levels of society. Merchants who would become temperance spokesmen stocked huge supplies of whiskey, and rich men joined freely in groups where bottles were passed from hand to hand. The flour mills in particular were community gathering places, and farmers waiting to use the mills lounged with the millers and with other local citizens and drank.50 Among laborers and building tradesmen, the dram was an indispensable part of daily wages. And in the workshops, drinking was universal. Not only independent craftsmen and shoemakers hidden away in boardinghouses, but men who worked directly under churchgoing proprietors drank on the job and with their employers. A store clerk remembered that Edwin Scrantom (he was the editor who expressed concern for unprayed-for apprentices and clerks) “often came into our store for a pitcher of ale to cheer up the boys in the printing offices nearby.”51 Only once in the early years is there record of drinking having caused trouble. In 1818 musicians in the town band—prominent professionals and master craftsmen among them—found themselves too drunk to play. Thereafter, they reduced consumption at rehearsals. 52

Liquor was embedded in the pattern of irregular work and

easy sociability sustained by the household economy. It was a bond between men who lived, worked, and played together, a compliment to the unique kind of domination associated with that round of life. Workmen drank with their employers, in situations that employers controlled. The informal mixing of work and leisure and of master and wage earner softened and helped legitimate inequality. At the same time drunkenness remained within the bounds of what the master considered appropriate. For it was in his house that most routine drinking was done, and it was he who bought the drinks.

That changed abruptly in the 1820s. Masters increased the pace, scale, and regularity of production, and they hired young strangers with whom they shared no more than contractual obligations. The masters were becoming businessmen, concerned more with the purchase of labor and raw materials and the distribution of finished goods than with production itself. They began to absent themselves from the workshops. At the same time they demanded new standards of discipline and regularity within those rooms. We shall see that those standards included abstinence from strong drink.53 Now workmen drank less often and less openly on the job. And when they drank, they shared the relaxation and conviviality only with each other, while masters sat in the front room or in another part of town dealing with customers and dreaming up new ways to make things cheaply and quickly.

After work, master and wage earner retreated further into worlds of their own. Masters walked down quiet side streets and entered households that had seceded from the marketplace. Separated from work and workingmen, they and their wives and children turned the middle-class family into a refuge from the amoral economy and disorderly society outside its doors. It was not only the need for clearheaded calculation at work but the new ethos of bourgeois family life that drove businessmen away from the bottle. For unlike the large and public households of 1820, these private little homes—increasingly

under the governance of pious housewives—were inappropriate places in which to get drunk. By 1830 the doorway to a middle-class home separated radically different kinds of space: drunkenness and promiscuous sociability on the outside, privacy and icy sobriety indoors.54

In the middle and late 1820s whiskey disappeared from settings that the middle class controlled. But in banishing liquor from their workshops and homes, proprietors reached the new limits of what they could in fact control. And it was at those limits that alcohol took on its symbolic force.

Workingmen were building an autonomous social life, and heavy drinking remained part of it. In 1827 Rochester contained nearly 100 establishments licensed to sell drinks. These were not great beer halls and saloons (they would arrive much later in the century) but houses and little businesses where workmen combined drinking with everyday social transactions. On the downtown streets a workman could get a glass of whiskey at groceries, at either of two candy stores, or at a barber shop a few steps from the central business intersection —all of them gathering places for men like himself.55 At night he could join the crowds at the theater, spending time before and after the show in the noisy and crowded barroom that occupied the basement. On the way home, he would pass the establishments of other licensed grogsellers, for they were everywhere in the workingman’s Rochester. The men who operated bars in the poorer neighborhoods shared the sensibilities and many of the experiences of their patrons, for fully 43 percent of them were wage earners themselves. These part-time barkeepers included thirteen journeymen and eight laborers, two boatmen, two teamsters, three clerks, and a pair of schoolteachers. A five-dollar license permitted them to sell drinks, adding to their incomes and fitting their households into the emerging pattern of working-class neighborhood life.

Alongside these kitchen barrooms stood businesses licensed to sell whiskey: food shops and small variety stores, taverns,

and the home workshops of a few of the smaller master craftsmen. These were social centers on a large scale, for many of them doubled as boardinghouses. Of shopkeepers and petty proprietors licensed to sell drinks in 1827 (N=23), 52 percent took in lodgers. (Among the 51 who did not serve drinks, the comparable figure was 8 percent.)56 These ramshackle establishments—“disorderly,” the newspapers called them—carried on traditions that had been abandoned in the workshops, maintaining an easy integration of economic, domestic, and leisure activities, and of life indoors with the life of the neighborhood. Perhaps typical was the bakery run by John C. Stevens on the canal towpath off Exchange Street. During the day Stevens and his family baked bread. But they stopped at odd times to serve drinks and talk with canal men and dock workers from the boat basin a few steps away. In the evenings they were joined by the journeyman carpenter and the schoolteacher who boarded in their home, and by whoever else decided to drop by, and the activities of the household merged imperceptibly with the flow of neighborhood life.57

The Stevens bakery was a lively and crowded place, lively in a very old way. Merchants and masters might peer down the towpath and see that functions they once performed—the provision of food and a place to sleep, whiskey and the companionship and relaxation that went with it—were being taken up by workingmen themselves, or by such questionable proprietors as John C. Stevens. It gave the old family governors something to ponder as they disappeared into their own secluded homes.

The link between drinking and violence was, of course, more than a figment of middle-class imaginations. Alcohol was surrounded by new, perhaps looser cultural controls. At the same time, workingmen experienced punishing changes in what they could expect from life, and some social drinkers took a turn toward the pathological. The laborer who stabbed a friend in 1828, the boat carpenter who beat a workmate to

death with a calking mallet in 1829, and the man who killed his wife in the middle of North St. Paul Street were all drunk and can all, I think, be put into that category.58 But we must also note that official intervention in working-class neighborhoods—and it came with increasing frequency—sometimes created violence where there had been none. In 1830 a Negro blacksmith turned on the constable who was arresting him for gambling and beat him unconscious. A few months later, neighbors rescued an offender before officials could get him off the block. And in 1833 a constable entered a grocery to quiet a disturbance and was kicked to death.59 The new neighborhoods were building an independent social life, and some workmen were demonstrating that they would meet outside meddling with force.

The drinking problem of the late 1820s stemmed directly from the new relationship between master and wage earner. Alcohol had been a builder of morale in household workshops, a subtle and pleasant bond between men. But in the 1820s proprietors turned their workshops into little factories, moved their families away from their places of business, and devised standards of discipline, self-control, and domesticity that banned liquor. By default, drinking became part of an autonomous working-class social life, and its meaning changed. When proprietors sent temperance messages into the new neighborhoods, they received replies such as this:

Who are the most temperate men of modern times? Those who quaff the juice of the grape with their friends, with the greatest good nature, after the manner of the ancient patriarchs, without any malice in their hearts, or the cold-water, pale-faced, money-making men, who make the necessities of their neighbors their opportunity for grinding the face of the poor?60

An ancient bond between classes had become, within a very short time, an angry badge of working-class status.

The liquor question dominated social and political conflict in Rochester from the late 1820s onward. At every step, it pitted a culturally independent working class against entrepreneurs who had dissolved the social relationships through which they had controlled others, but who continued to consider themselves the rightful protectors and governors of their city.