WATERFOWL

Swans, Geese, and Ducks

47. Tundra Swan [Common American Swan] i

Cygnus columbianus [Cygnus Americanus]

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

(Flight calls)

The park swan, which floats about in narcissistic adoration, comes from Europe. But we do have two native swans, magnificent untamed birds that were here when the first anchor chains rattled off the coast. One, the trumpeter swan of the northwest, has become one of the rarer North American birds. The other, the tundra swan, or common American swan as Audubon called it, is doing very well these days.

Tundra swans spend the summer north of the Arctic Circle, north and west of Hudson Bay. Forty to fifty thousand of them might be scattered in pairs and little groups over thousands of square miles of tundra. When ice begins to lock the bays, they start southward in long gooselike wedges, conversing excitedly with whoops and soft trumpeting laughter. Then comes a parting of the ways: one large faction splits off to the west, heading for the great central valleys of California. The rest proceed to the Atlantic, past Lake Huron and Lake Erie, where some rest for a while, then across the Appalachian ridges to the broad waters of the Chesapeake and the bays of North Carolina. It is a long journey. Occasionally in spring, when returning flocks rest on the Niagara River, some have been carried by the swift current over the falls.

In this composition Audubon has included three yellow water lilies which he believed to be a new species. He proposed the name “Nymphea Leitneria.”

Cygnus buccinator [Cygnus Buccinator]

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

(Pair calls)

The trumpeter swan, larger and deeper-voiced than the more numerous tundra swan, apparently enjoyed a wider distribution in North America when our nation was young. Although it did not reach the Atlantic coast, Audubon knew it well on the Ohio and Mississippi. He stated, “Trumpeters are frequently exposed for sale in the markets, being procured on the ponds of the interior and on the Great Lakes leading to the waters of the Gulf of Mexico.” He also stated that they were abundant at times in Texas during the winter months. If he was correct, all of that changed drastically. By the 1930s the bird was on the endangered list. Since then, under protection and management, it has made a partial comeback in the northwest and is no longer considered endangered. Today the main population exists in south and central Alaska, migrating to British Columbia and Washington for the winter. Smaller pockets of transplanted trumpeters exist in Alberta, Oregon, Idaho, Nevada, Montana, Wyoming, South Dakota, and elsewhere In 1970, the total population was estimated to be 4,000 to 5,000 birds, of which 2,800 were in Alaska and perhaps 800 in the contiguous United States; of the latter at least 160 (80 pairs) were in Yellowstone National Park.

Today some academics lump the whooper swan, Cygnus cygnus, of Europe and Asia with the trumpeter, categorizing them as merely two races of a single species. The whooper differs from the trumpeter in having a large area of yellow at the base of its bill.

Cygnus buccinator [Cygnus Buccinator]

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

(Pair calls)

On December 16, 1821, while in New Orleans, Audubon noted in his journal that he had been drawing a young trumpeter swan (this bird) that had been shot by his hunter, Gilbert, on Lake Barataria. The grayish plumage of the juvenile is held for about a year but turns quite white by the second year.

This large swan once enjoyed a wide distribution in the middle states, where it no longer appears. Audubon wrote, “The Trumpeter Swans make their appearance in the lower portions of the Ohio about the end of October. They throw themselves at once into the larger ponds or lakes at no great distance from the river, giving a marked preference to those which are surrounded by dense and tall cane-brakes, and there remain until the water is closed by ice, when they are forced to proceed southward. During mild winters I have seen Swans of this species in the ponds about Henderson until the beginning of March, but only a few individuals, which may have staid there to recover from their wounds. . . . The waters of the Arkansas and its tributaries are annually supplied with Trumpeter Swans, and the largest individual which I have examined measured nearly ten feet in extent and weighed above 38 pounds. The quills, which I used in drawing the feet and claws of many small birds, were so hard, and yet so elastic, that the best steel-pen of the present day might have blushed, if it could, to be compared with them.”

Branta canadensis [Anser Canadensis]

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

(Pair calls; Flight calls)

Audubon painted all of his birds life-size. This occasionally created problems of design when he endeavored to fit very large, long-necked birds within the confines of the page. In this Canada goose portrait he contrived to solve the dilemma by doubling back the neck and head. When drawing large long-legged waders such as the great blue heron and the flamingo he would drop the head toward the feet.

The Canada goose, like the robin, is a symbol of spring to those who are snowbound until March in the northern parts of the United States and in Canada. The returning flocks of geese usually are heard before their long wedges are seen in the sky as they knife northward. Large flocks travel long distances overland from the coastal bays, stopping only to rest and to feed. They may tarry awhile around the Great Lakes until the ponds and marshes farther north open up.

Canada geese apparently bred widely in the northern states in Audubon’s day, but by the beginning of this century few nested south of the Canadian border. In recent years resident populations have become reestablished along the Atlantic seaboard at least as far south as Maryland and also at some inland localities. In general, geese now are doing very well (certainly better than some of the ducks), because they can graze in the stubble fields and are not as dependent on aquatic food. Enormous flocks congregate at some of the refuges such as Horicon Marsh in Wisconsin, sometimes creating problems on adjacent farms.

51. Canada Goose [Hutchins’s Barnacle Goose] i

Branta canadensis [Anser Hutchinsii]

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

(Pair calls; Flight calls)

This small race of the Canada goose from Baffin Island and the other arctic lands north of Hudson Bay formerly was regarded as a distinct species. Audubon called it “Hutchins’s Barnacle Goose,” a name he later changed to “Richardson’s Goose,” in honor of the explorer who found it abundant around Hudson Bay where it was long mistaken for the Brant, or an emaciated Canada goose. The specimen from which Audubon worked was presented to him by his “highly esteemed and gallant friend Captain James Clark Ross.” He wrote, “I have embraced the opportunity of laying before you a representation, the first I believe that has yet appeared, of Hutchins’ Goose. . . . For fifteen months, rendered trebly long and wearisome by heavy and difficult marches, the most amiable and accomplished traveller [Ross] carried with him many specimens of rare birds, with the view of contributing to the advancement of our knowledge.”

This goose is now considered but one of a dozen recognized races of the Canada goose, ranging from the giant Canada goose, weighing about fourteen pounds, to the Hutchins’s goose and cackling goose, which tip the scales at only four and one-half. One race, the Bering Canada goose from the Commander and Kurile islands, is extinct. The giant Canada goose of the Great Plains was also thought to be extinct, or nearly so, until a captive flock was discovered. It was propagated in several wildlife refuges until it is now abundant. Actually, the various races intergrade, so the species may be regarded as clinal, blending from populations of large birds to small ones.

Branta bernicla

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

This small black-chested, black-necked goose, the size of a mallard, breeds in the High Arctic, north and west of Hudson Bay. It migrates overland in a southeasterly direction to the lower St. Lawrence River, travelling from there to the coast. It winters from New England to the Carolinas, favoring eelgrass as its principal item of diet. The paths and extent of the Brant’s migrations were unknown in Audubon’s day.

During the early 1930s there was a die-off of eelgrass along much of the Atlantic coast, causing the bird to drop drastically, perhaps to less than ten percent of its previous numbers. Although subject to wide fluctuations in population, in recent years it has made a considerable comeback.

Audubon wrote that he considered “the flesh of this bird as excellent food. The young in autumn, or about the time of their first appearance on our eastern coast, Massachusetts for example, are tender, juicy, and fat; and are as well known to the epicures of Boston as the more celebrated Canvass-back is to those of Baltimore.” He represented a pair that were shot in spring, probably not far from Philadelphia in the bays of coastal New Jersey.

Branta leucopsis

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

The barnacle goose usually is regarded as an accidental straggler from Europe, but it has appeared in at least a score of records in recent years from such disparate localities in North America as Labrador, Quebec, New Brunswick, Ontario, Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Oklahoma, North Carolina, and Alabama. Some of these may have been escapes from zoos or private collections, but inasmuch as the bird breeds in eastern Greenland, there is always the possibility of a genuine stray.

Audubon never saw one, but he wrote, “Several old gunners on the coast of Massachusetts and Maine who were Englishmen by birth, assured me they had killed Barnacles there and that these birds brought a higher price in the markets than the common Brent Goose. The Prince of Musignano states in his synopsis that they are very rare and accidental in the United States and Mr. Nuttall says that they are ‘mere stragglers.’ For my part I acknowledge that I have never met with one of them, either along the coast or in the interior; although I have seen beautiful mounted specimens. Being neither anxious to add to our fauna nor willing necessarily to detract from it, I have figured a pair of these birds with the hope that erelong the assertions of the gunners may be verified by the slaughter of many geese.” The birds in this plate probably were drawn in England from museum specimens.

54. Greater White-fronted Goose [White-fronted Goose] i

Anser albifrons

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

(Flight calls)

This attractive gray goose, readily identified by the white patch at the base of the bill and the black splotches across the belly, is most numerous in the western parts of North America. It breeds on the Arctic tundra north and west of Hudson Bay and migrates southward, mainly west of the Mississippi River, to its wintering grounds along the coast of Texas and in the valleys of California. A small population also exists in southwestern Greenland, possibly accounting for the casual stragglers that appear along the Atlantic coast from time to time.

Audubon reported that when residing on the banks of the Ohio River in Kentucky, “A winter never passed without my seeing a good number of them; and at that season they are frequently offered for sale in the markets of New Orleans.”

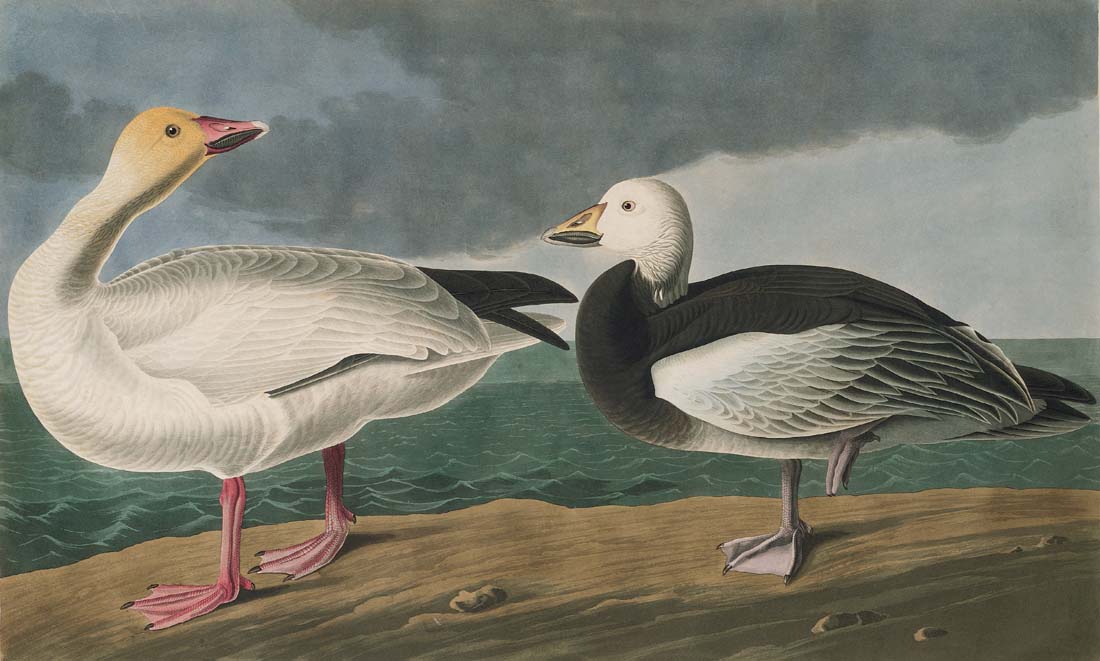

Chen caerulescens

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

(Flock calls)

Although for many years ornithologists separated the two color morphs of the snow goose—the white and the “blue”—as two distinct species, Audubon was of a different opinion. He regarded them as one, but thought that the “blue” form was the young bird, which he believed retained that plumage several years before becoming white with black primaries. For this reason he presented the two together in one plate. He wrote, “I am unable to inform you at what age the Snow Goose attains its pure white plumage. There can be little doubt that this species breeds in its gray plumage when it is generally known by the name of Blue-wing Goose.” It was in relatively recent years that careful research on the breeding grounds in the Canadian Arctic established conclusively that the two were color morphs of the same species and that there were often mixed pairs and intermediates.

The snow goose is widespread in North America, breeding around Hudson Bay and in the High Arctic. It winters along the central Atlantic and Gulf coasts and locally inland in the southern prairie states as well as in the valleys of California. In migration the concentrations are very impressive as the masses of birds stream across the sky in long ribbons, the white birds etched against the azure sky in contrast to their dark associates. The blue form winters in greatest number along the coasts of Texas and Louisiana.

Anas platyrhynchos

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

(Female decrescendo; Female quacks in flight; Male calls)

The green-headed “puddle ducks” in the parks are mallards, as are the white “Pekin ducks” on the farm. Most domestic ducks, in fact, are descended from the wild mallard—the most widely distributed, perhaps the most numerous, and certainly the most hunted duck on earth. On our continent it is common wherever there are lakes and marshes except in the extreme northeast, from New England north. There the black duck (a brother under the skin) replaces it.

Undoubtedly mallards were once more numerous. In 1832, Audubon found them in Florida in flocks that darkened the air. There are still great flocks today, and they are extending their breeding range to the northeast. But a continental population of all ducks that may have numbered between 200,000,000 and 500,000,000 in Audubon’s day (just a guess) had dropped to 55–60 million by 1978. The reason is obvious. From a few hundred thousand guns at most in use in Audubon’s era, the duck-hunting pressure increased this number to millions. The ducks could not keep pace; on the contrary, during those years 100,000,000 acres of marshland (the duck nurseries of the continent) were drained for agriculture to help feed the explosively increasing human population. It is no accident that the daily bag limit of ducks has dropped from twenty-five per man not so many years ago to a mere four in more recent years. There just are not enough ducks to go around.

57. Mallard X Gadwall hybrid [Brewer’s or Bemaculated Duck]

Anas platyrhynchos X strepera

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

When Audubon shot this bird near New Orleans in February, 1822, he thought it might be a new species, but he was not sure. It was in the company of seven or eight canvasbacks. Although he gave it a new name, Anas Breweri, in honor of his esteemed friend Dr. Brewer, he very astutely suspected that it might possibly be a hybrid between the mallard and perhaps the Gadwall, to which it also bore a superficial resemblance. In this he was quite correct.

Mallard hybridize quite often with other closely related ducks. Some years ago a mallard-gadwall hybrid spent the entire winter on the 59th Street Lake in Central Park in New York. This bird, a male, lacking the company of its kind, actually took up with a female black duck; one could only wonder what the resulting three-way hybrid would be like. Mallard-black duck hybrids are frequent, and the more universal and adaptable mallard eventually may eclipse the black duck, by taking over its habitat and genetically swamping it out.

58. American Black Duck [Dusky Duck] i

Anas rubripes

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

(Quack; Flight quack)

The black duck, or “dusky duck,” as Audubon called it, can readily be identified in flight overhead by its uniform dark body contrasting with the flashing white wing linings. Audubon drew the bird at the right in a rather contorted pose so as to show this important field characteristic.

Unlike its close relative the mallard, the black duck is confined to the eastern half of the continent. There is no question that it has been declining in recent years due to genetic competition with the more adaptable mallard, which has expanded its breeding range eastward through the Great Lakes to coastal New England, the ancestral stronghold of the black duck. A secondary cause for the decline of the black duck may be over-harvesting during the shooting season. There is some dispute about this. Some wildlife managers firmly believe the season should be closed on the black duck so as to give it a chance to regain some of its former numbers or until a more stable optimum population level is reached.

In Audubon’s day there were no legal restraints. He described these ducks as delicious eating; in his estimation, “much superior to the more celebrated Canvass-back Duck. In our eastern markets the price of these birds is from a dollar to a dollar and fifty cents the pair. They are dearer at New Orleans, but much cheaper in the states of Ohio and Kentucky, where they are still more abundant.”

Anas strepera

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

(Female “quacks”; Male “burp” call; “Descrescendo” call; “tickety-tickety-tickety” feeding call)

The modest-looking gadwall can be separated readily from the somber-colored black duck by its grayer coloration contrasting with its brownish head and jet black tail coverts. In flight a white square shows on the trailing edge of the wing. Females are not unlike female mallards except for the white wing patch. In recent years the gadwall has spread eastward from its principal domain in the western and mid-western prairies to the Atlantic coast, where it now breeds locally from Maine to North Carolina. This range expansion has been due, in part, to marsh management in the coastal states and partly to deliberate introduction of breeding stock. The concept of wildfowl management was unknown in Audubon’s day. The huntsman scarcely thought about the future. During the last half century, duck hunters, wishing to perpetuate their sport, have seen to it that waterfowl will not go the way of the passenger pigeon. To this end many federal and state refuges have been created.

60. Northern Pintail [Pintail Duck] i

Anas acuta

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

(Male “whee” whistles and female repulsion calls)

This elegant marsh duck that sits so lightly on the water, its needlepointed tail elevated and its slim neck alert, has a very wide distribution around the northern parts of the world, breeding across Canada and Alaska as well as the northern parts of Europe and Asia. Although in the continental United States it is more typical of the western portions of the country during the summer months, it migrates eastward to the marshes along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts where many spend the winter. During migration it can be found on most any suitable pond or marsh where the dabbling ducks gather. Audubon knew the bird well during its passage along the Ohio River where he lived for some years, and he spoke of its “liking for beechnuts in search of which they even ramble to a short distance into the woods.” He added, “Were this duck to feed entirely on beechnuts I have no doubt that its flesh would be excellent. It feeds on tadpoles in spring and leeches in autumn, while during winter a dead mouse, should it come its way, is swallowed with as much avidity as by a mallard. To these articles of food it adds insects of all kinds and, in fact, it is by no means an inexpert flycatcher.” And thus Audubon showed a pair of these birds in animated pursuit of an insect. The background and the insect were painted in oil, probably by Audubon’s son Victor.

Anas crecca

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

(Male whistle, display, chatter; Female decrescendo)

When in flight with mixed flocks of other marsh ducks, teal are readily recognized by their small size and tight flocks. If, when they wheel in the air, they show pale wing-patches they are blue-winged teal; but if they lack these they are green-winged teal. In sunlight the patch on the rear edge of the wing flashes a deep iridescent green.

The green-wing is a wide-ranging bird, breeding in the northern parts of the Northern Hemisphere and wintering south to Central America and the West Indies. Like other marsh ducks they seem to be far less numerous than in Audubon’s time. He wrote, “At the first arrival of the Green-winged Teal in the western country (Kentucky) I have seen upwards of six dozen shot by a single gunner in the course of one day.” Today, because of the far greater number of men who pursue waterfowl, and the diminished number of ducks to go around, strict bag limits are imposed. Any gunner who shot 72 ducks in one day would not brag about it because he quickly would be hauled into court. Game management as we know it today is no longer guesswork; it is a science. Bag limits and closed seasons are sometimes subject to political pressures. The limiting factor in this era of expanding human populations is the availability of nesting marshes. These are becoming fewer and fewer because of drainage and other development.

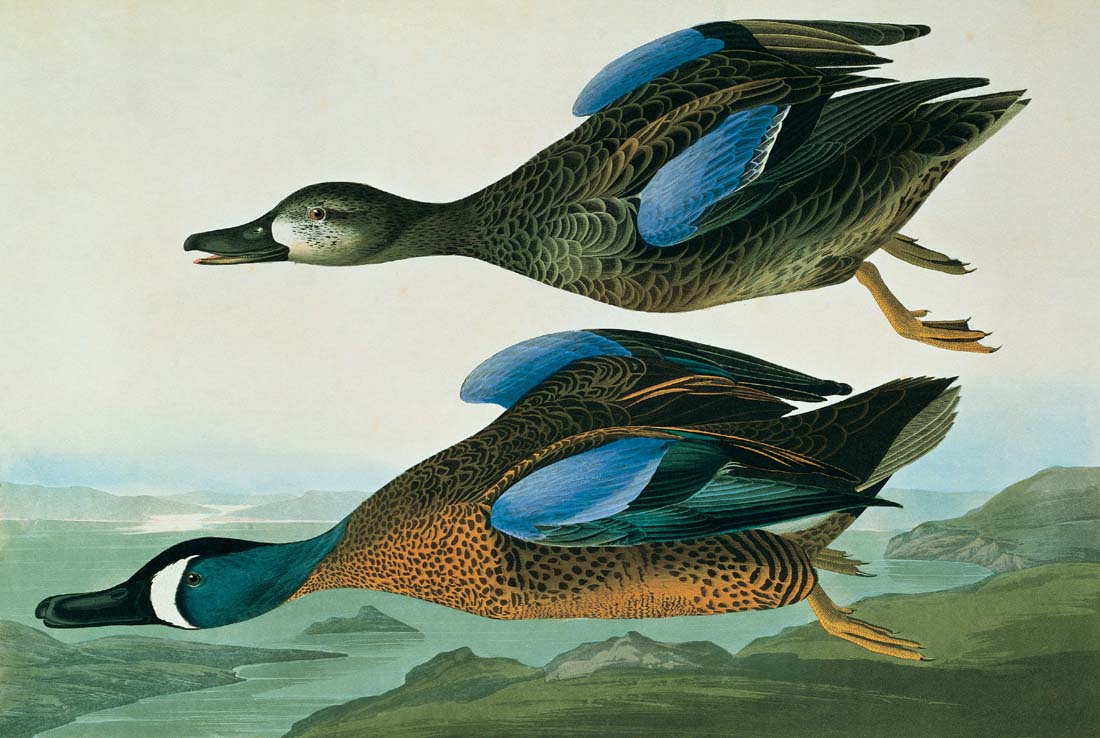

Anas discors

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

(Whistles and calls in flight; Female quack; Decrescendo call)

Teal are little half-sized marsh ducks that bunch in tight flocks, twisting and turning as they perform their aerial evolutions. When the upper surface is presented, the large chalky blue wing-patch on the forewing of the blue-winged teal separates it from the green-winged teal. In addition to the diagnostic wing-patches the male has a crescent-shaped white face patch.

In Audubon’s day, duck shooting could not have been called properly a sport; it was pure slaughter. In his account of the blue-winged teal he writes, “During their first appearance in autumn, when you were apt to meet with a flock entirely composed of young birds, you may, by using a little care, kill a considerable number at one shot. I was assured by a gunner residing at New Orleans that as many as 120 had been killed by himself at a single discharge. I myself saw a friend of mine kill 84 by pulling together the triggers of his double-barreled gun.”

This little duck enjoys a very wide distribution in the freshwater marshes across the continent, from New England and the Maritime Provinces to the Pacific, and from the Canadian prairies to the Texas coast. In the winter many proceed to the West Indies and South America. This is not one of Audubon’s better compositions. The birds are rather static and look as though they had been thrown through the air like footballs.

63. American Wigeon [American Widgeon] i

Anas americana

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

(Male slow whistle; Female call)

Baldpate was the name coined by hunters for this handsome dabbling duck. Birders also knew it by this very appropriate name until recently when the American Ornithologists’ Union and the American Birding Association decreed that American wigeon, the name Audubon used, should be the official name. A similar species, the European wigeon, distinguished by its rufous brown head, appears occasionally in the flocks of American wigeon on this side of the Atlantic, but obviously Audubon never noted it in America.

The shiny white crown of the male is the field mark of this rusty colored duck that rides so buoyantly on the surface of ponds and lakes. It summers for the most part in the northwestern parts of the continent and migrates abundantly through the Great Lakes and the Mississippi Valley to ponds, lakes, and bays along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts. Another large contingent winters in the Pacific states. Audubon surmised that they bred in Texas because he saw them there so late into the month of May and they seemed to be nesting. He was assured by friends that they actually did nest there, but they certainly do not do so today.

This is another of Audubon’s mixed medium works, executed in pencil, pastel, watercolor, and oil. The original background was painted out and repainted, possibly by his son Victor. Havell, the engraver, then reversed the positions of the male and female ducks.

64. Northern Shoveler [Shoveller Duck] i

Anas clypeata

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

(Male call; Female call; Male calls)

The postures of some of Audubon’s birds seem rather contrived, but he may be forgiven because he was always aware of two objectives: to create a dynamic composition and to show as many important details as he could—hence the spread wing of the male shoveler, which would not have revealed its colorful pattern had the bird been shown at rest or simply walking about.

Shovelers are widespread in the northern hemisphere, being found across North America, Europe, and Asia, and also (in the winter months) south to northern South America and Africa. In North America the shoveler is much more widespread in the west, breeding from Alaska to California. East of the prairies it is a very local summer resident, but during autumn and winter western birds invade the ponds and marshes of the Atlantic seaboard, mingling with the more abundant mallards, black ducks, pintails, teal, and other freshwater dabblers. When swimming, shovelers sit low, their big spoon-shaped bills sifting goodies from the muddy water. In flight the big bill makes the wings seem to be set rather far back, as though the bird was not well-balanced. By midsummer the male molts into a drab plumage known as the “eclipse,” which is very much like the modest brown plumage of its mate. By the end of summer it commences a second molt in which it regains its bright pattern.

65. Wood Duck [Summer or Wood Duck] i

Aix sponsa

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

(Male call; Female calls)

This, the most beautiful North American duck, actually was endangered in the eastern United States during the early years of this century. The wood duck or “summer duck,” not as highly migratory as most other waterfowl, was then extremely vulnerable because spring shooting, not yet outlawed, was in progress at the very time that the bird was courting and setting up housekeeping. Things became so critical that the National Audubon Society (then known as the National Association of Audubon Societies) initiated a breeding program in Connecticut, raising birds under artificial conditions and setting out large numbers of nesting boxes for their convenience.

The wood duck does not nest on the ground or among the reeds as do most other ducks. It lays its eggs (up to 15 or more) in a tree cavity. Audubon occasionally found them occupying the abandoned holes of ivory-billed woodpeckers. Although a wood duck can squeeze into a hole that would seem too small to admit it, good nesting sites are often at a premium. To counteract this, game departments often build specially designed boxes, which are placed on poles several feet above the water where raccoons and other predators cannot reach them.

A few hours after hatching, the babies simply climb from the feather-lined nest to the entrance hole and jump out—even though it might be twenty feet or more above the hard forest floor. They survive and soon head for the nearest water with their nestmates.

66. Redhead [Red-headed Duck] i

Aythya americana [Fuligula Ferina]

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

(Female kurr-kurr-kurr; Male whistle call or meow)

The two birds represented in this plate were given to Audubon, as he wrote, “by my friend Daniel Webster, Esq., of Boston, Massachusetts, whose talents and accomplishments are too well known to require any eulogium from me.” Audubon was of the opinion that the redhead was the same as the pochard of Europe, a similar species that is somewhat between the redhead and canvasback in appearance.

The male redhead is readily differentiated from its near relative the canvasback by its rounder head and grayer coloration. The canvasback is whiter with a very long, sloping profile. The main breeding stronghold of the redhead is in the prairie regions of the west, but a few breed locally to the Great Lakes and eastward. In migration, large flocks pass through the Great Lakes to the Atlantic coast; many strike south through the Mississippi Valley to the coastal bayous of Louisiana and Texas, others turn west to the California valleys. Heavily hunted, the redhead is subject to wide fluctuations in numbers.

Audubon reported that redheads were offered for sale in the Baltimore markets in great numbers. They were sold at 75 cents a pair, which was lower by 25 cents than in New Orleans. He knew of a Frenchman in New Orleans who caught them in nets by the thousands, then sent them to market alive in cages. In those days there were no restrictions, no seasons, no bag limits. Ducks were a marketable crop, to be harvested in any manner possible.

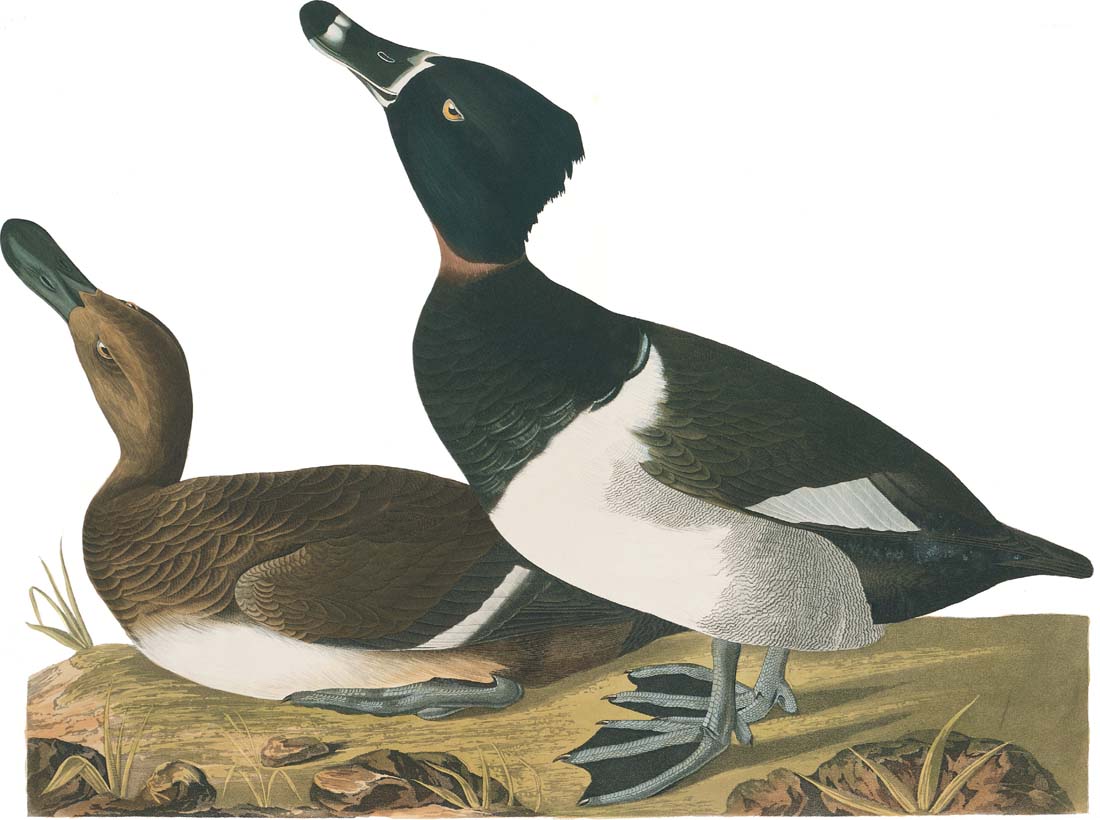

Aythya collaris

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

(Male call, female call)

Ring-necks, when rafted with their close relatives the greater and lesser scaup ducks, can be distinguished instantly by their black backs. The dark bill is marked by a bold white ring, so that a more appropriate name would have been ring-billed duck. The dull chestnut ring that encircles the bird’s neck is all but invisible under ordinary circumstances. Wilson, Audubon’s contemporary, supposed the ring-necked duck to be identical with the tufted duck of Europe. Lucien Bonaparte, the Prince of Musignano, first pointed out the difference between this species and its Old World counterpart. In recent years the ring-neck has extended its breeding range eastward across Canada to the Maritime Provinces. This population increase may have been helped by the great number of freshwater reservoirs built in the middle and southern states, offering new wintering grounds and greater winter survival. The ring-neck is not as much a bird of the coastal bays as are the two scaups or the canvasback and redhead. It prefers wood-rimmed lakes and reservoirs while on migration and in the winter.

The original of this painting was done in pastel, watercolor, and oil. Audubon often painted in this mixed manner.

68. Canvasback [Canvass-back Duck] i

Aythya valisineria

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

(Quacks; Calls)

Traditionally, the canvasback has been regarded by epicure sportsmen as the aristocrat of waterfowl, whose flesh on the table is second to none. Audubon did not agree with this evaluation, rating several other ducks superior. The canvasback is a prairie duck in summer, but in winter one of its main resorts is the Chesapeake. This print, which brings a very high price in the collectors’ market, appropriately shows a view of Baltimore. Audubon wrote, “In the background is a view of Baltimore which I have had great pleasure in introducing, on account of the hospitality which I have there experienced, and generosity of its inhabitants, who, on the occasion of a quantity of my plates having been destroyed by the mob during an outburst of political feeling, indemnified me for the loss.”

In recent years the canvasback has periodically been of concern to conservationists and waterfowl biologists. Its numbers have fluctuated, sometimes because of drought on the breeding grounds, at other times because of overkill. To balance the ledger, restrictions have been imposed on the gunning fraternity. But even in Audubon’s day the bird was dwindling. Sharpless of Philadelphia wrote, “I have met with persons who have assured me that the number has decreased one-half in the last fifteen years.” He spoke of a man “with a gun of great size fixed up on a swivel in a boat and the destruction of game on their feeding flats have been immense; but so unpopular is the plan that many schemes have been privately proposed for destroying his boat and gun.”

69. Greater Scaup [Scaup Duck] i

Aythya marila [Fuligula Marila]

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

(Female call; Male calls)

Audubon was much confused about the two scaup ducks, the greater and the lesser, as many birders are to this day. Only one species, the greater, was recognized at the time he made this drawing, which does, indeed, seem to be a greater scaup. When he wrote his account in the Ornithological Biography he was under the impression that he was writing about the same species that other ornithologists of his day had written about. Later, in his octavo Birds of America, he changed his mind: “It is extremely curious that none of the authors who have written on the ornithology of our country, should have discovered that, another species of Scaup Duck also exists, and that abundantly too, throughout the United States. . . . Until about two years since, I thought that I had given the history of the Common Scaup Duck, and now all that I have said of ‘Fuligula Marila: must now be applied to Fuligula Mariloides of Vigors. The bird which has been described in my Ornithological Biographies and figured in my large plates, being in fact Fuligula Mariloides . . . differing from the Fuligula Marila in size, being considerably smaller than the latter.” However, his painting belies this. He drew it in New Orleans, where the lesser is the dominant scaup, and for this reason some writers have labeled it the lesser scaup, but the extent of the white wing-stripe onto the primaries indicates otherwise. In certain other respects the drawing is indeterminate.

70. Common Goldeneye [Golden-eye Duck] i

Bucephala clangula [Fuligula Clangula]

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

(Male display; Female call; Wing whistle)

The large, round, white spot between the eye and the bill of the male goldeneye is its most distinctive field mark. The female is more modest in appearance: gray with a chocolate-brown head, separated from the gray chest by a broad white collar. This cold-weather duck whistles or “sings” with its wings as it flies swiftly over the lakes, ponds, and streams. In such places the “whistler” is often the only duck to be found during the winter months, except for the common merganser. It winters wherever it can find open water, from southern Canada southward to the Gulf states and California. In summer it ranges across Canada and the cool northern fringes of the U.S., nesting like the wood duck and hooded merganser in the hollows of trees near forest lakes. Audubon describes the only nest he ever found: “The female left it, probably to go in search of food, whilst I was sitting under the tree. Hunger and fatigue vanished; and in a few minutes I was thrusting my arm into the cavity of a large broken branch. Nine beautiful, greenish, smooth eggs, almost equally rounded at both ends, were at my disposal. Not being aware of the necessity of measuring or keeping eggs, I roasted them on some embers, and finding them truly delicious, soon satisfied my hunger. While I was eating them, the bird returned, but no male was seen.” He was never to find another nest.

71. Barrow’s Goldeneye [Golden-eye Duck] i

Bucephala islandica [Clangula Vulgaris]

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

(Female call; Wing whistle)

When Audubon painted this portrait of the male Barrow’s goldeneye he did not recognize it as a different species. In his handwriting on the original colorplate he merely says, “Goldeneye Duck, Clangula Vulgaris, male, summer plumage.” Nor is Barrow’s goldeneye mentioned in his subsequent octavo, Birds of America. However, in the synonymy we note the inclusion of CLANGULA BAROVII, Rocky-mountain Garrot, which was described by Swainson and Richardson in their Fauna Borealis Americana, obviously this species.

Audubon painted this composition in 1838 while in London. The specimen was given to him by the Earl of Derby, who had received it from a collector who accompanied an expedition to the Canadian Arctic. Later the engraver, Havell, added the water and sky to the plate.

Barrow’s goldeneye, which can be told from the common species by the white crescent before its eye, has a disjunct summer range in Iceland, northern Labrador, and the mountains of northwestern North America—a world range very similar to that of the harlequin duck, which prefers rougher water. Although Barrow’s goldeneye winters sparingly along the northeast coast from the Gulf of St. Lawrence to New England, Audubon never encountered it.

72. Bufflehead [Buffel-headed Duck] i

Bucephala albeola [Fuligula Albeola]

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

(Female call; Courtship chase)

The chubby little bufflehead, with its white bonnet, can be confused with no other North American duck except possibly the hooded merganser, which is racier, with dark chestnut instead of white sides. The dark females are easily recognized by the white ear-patch on their chocolate-brown heads. Like its larger relative the goldeneye, it is a diver, inhabiting the cold lakes across Canada to Alaska during the summer months and wintering across the continent from the Maritime Provinces and the Great Lakes to the Gulf states and California. During migration it is widespread on lakes, ponds, and rivers; but during the winter it prefers salt bays not too far from the ocean.

Audubon noted that in different regions of the country this species was known variously by such names as spirit duck, butterbox, marionette, dipper, and die-dipper. “The marrionette—and I think the name a pretty one—is a very hardy bird for it remains at times during extremely cold weather on the Ohio when it is thickly covered with floating ice. . . . I have sometimes been much amused to see the apparent glee with which these little dippers would dive at the repeated snappings of a miserable flint lock, patiently tried by some vagrant boys who, becoming fatigued with the ill luck of their piece, would lay it aside, and throw stones at the birds, which would appear quite pleased.”

73. Oldsquaw [Long-tailed Duck] i

Clangula hyemalis [Fuligula Glacialis]

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

(Male calls)

“Long-tailed Duck,” the name applied in England to this smart-looking sea duck, was the name Audubon used. Oldsquaw, the colorful North American name, derived from local lore, refers to the bird’s talkative habits. Its rather noisy cries sound like ow-owdle-ow, or with a stretch of the imagination, owl-omelet. Another phonetically derived name for it was “south-southerly.”

Oldsquaws are circumpolar, ranging throughout the arctic and subarctic regions of both the New World and the Old, resorting to tundra ponds to raise their families. In winter, except for the Great Lakes, where they can be very common at times in the deeper ice-free waters, they seem to prefer the salt water of the Atlantic and Pacific. They are easily recognized, in flight over the sea, by their white bodies and totally dark wings, the only ducks so patterned. The long needle-like tail of the males suggests the similar tail of the pintail, but this species is a deep-water diver, whereas the pintail, a freshwater dabbler, is not.

Because oldsquaws were generally tough and fishy, they were brought to market, Audubon wrote, “plucked, with the head and feet cut off [so they could not be identified] and called by the vendors by all names excepting Oldwives, Squaws, Noisy Ducks or South-Southerlies.”

Taking illustrator’s options, Audubon mixed the seasons by showing two males, one in summer, one in winter plumage, as well as a female with three of her ducklings. He stated that it was “the first figure ever given of an adult female, accompanied with as many younglings as I could conveniently introduce.”

Histrionicus histrionicus [Fuligula Histrionica]

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

The harlequin is well named. This bizarre duck is addicted during the summer to rushing mountain streams, while in the winter it tends to seek rocky coasts where again it revels in turbulent waters. To most birdwatchers the harlequin is a rare find, but perhaps this is due to its rather inaccessible habitat. Its distribution is curiously disjunct—the mountains of northwestern North America and the mountain streams of Labrador and Iceland. In winter it seeks the sea coasts, ranging down our eastern shores to Long Island. Rarely, it visits the Great Lakes. Audubon mentions having obtained an egg from a Mr. Atkinson who found it in Ireland. This must have been a mistake and perhaps should have read “Iceland.”

Audubon comments on his painting, “I have the pleasure of presenting you with three figures of the Harlequin Duck, one a male in all the perfection of its spring plumage, the bird having attained complete maturity, another male two years old, and an adult female shot in the pairing season. No figures of the adult male or of the female have, I believe, hitherto been published.” In his journal he referred to this species as the “Lord and Lady Duck.” He reported that few persons shot it for its flesh, “not that it is inferior as food to other deep-diving ducks, but because it is comparatively small, and difficult to be obtained.”

Camptorhynchus labradorius [Fuligula Labradora]

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

This, the only North American duck to become extinct, was first described by Gmelin in 1788. It is believed to have nested on islands along the north shore of the Gulf of St. Lawrence and Labrador, and possibly farther north. Labrador ducks were not considered good eating, but milliners sought their feathers until 1860, when there were too few birds left to be profitable. On their main wintering grounds on Long Island they were soon shot out, the last confirmed specimen taken in 1875 (there is an unsubstantiated report three years later at Elmira, N.Y.). Although Audubon’s son, John Woodhouse Audubon, was shown several abandoned nests in Labrador that may have been of this species, not a single bona fide egg is known, and only 42 specimens of the bird exist in all the museums of the world. The two shown here were sent to Audubon by Daniel Webster, who shot them himself on Martha’s Vineyard.

Paul Johnsgard wrote, “Interred within the few skins, mounts and bones that are scattered throughout the world’s museums like the deteriorating leaves of a now-dead oak are the genes and chromosomes that represented the species strategy for survival in a hostile world. . . . It is approximately a century since the Labrador ducks made their last flights from their breeding grounds to the vicinity of Long Island; in that period our concern has gradually changed from the problems of how birds can survive modern man to the question of whether mankind can survive modern man.”

76. Steller’s Eider [Western Duck] i

Polysticta stelleri [Fuligula Stelleri]

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

Steller’s eider, discovered by Georg Wilhelm Steller on the northwestern coast of Alaska, was unknown to Audubon, who was unable to secure one to paint until his son, John Woodhouse Audubon, found a fine specimen in the museum at Norwich, England, and drew this plate from it. Havell added the head of the second male, faithfully copying the one in the foreground.

This arctic species breeds in the coastal tundras of Siberia and locally along the coasts of northern Alaska. It winters in the Aleutians and along the Alaskan Peninsula, where the winter population has been estimated to be about 200,000, with the heaviest concentrations at Bechevin Bay, Izembeck Bay, and Nelson Lagoon. At this season considerable numbers are also seen in northern Norway, especially at Varanger Fjord. The main breeding places are usually on the tundra some distance inland from salt water, but the rest of the year these hardy sea ducks swim and dive along rocky coasts.

77. Common Eider [Eider Duck] i

Somateria mollissima [Fuligula Mollissima]

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

(Male coo, female cluck)

Audubon has sometimes been accused by modern ornithologists of over-dramatizing his subjects. This animated composition of a trio of eiders risks this criticism, but it is almost certain that it was inspired by an incident that he had actually witnessed—perhaps during his Labrador cruise when he became very familiar with these striking sea ducks. Eiders are probably as abundant today as they were in Audubon’s time, when they could be purchased in the Boston markets for 75 cents per pair. Although they are still hunted, they are no longer prized as much by wildfowlers and epicures. Great flocks numbering many thousands winter on the shoals off Monomoy on Cape Cod and many can also be seen offshore at Martha’s Vineyard, but only a relative few reach Long Island. On the Maine coast and to the east in the Maritime Provinces they appear to be breeding in greater numbers than they did fifty years ago.

Eiderdown, gathered from the nests of the sitting females, has long been an article of commerce. In Iceland, where eider farms are managed scientifically, the industry is an important part of the economy. With similar management, insuring the protection of the birds, the gathering of down could be profitable elsewhere because the species is found widely on both sides of the North Atlantic and North Pacific.

Somateria spectabilis [Fuligula Spectabilis]

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

(Male coo, female clucks; Female defensive calls at nest)

The king eider with its improbable head ornamentation is perhaps the most bizarrely beautiful of all sea ducks. Circumpolar, it nests on the Arctic tundra of both hemispheres, descending in winter to the latitudes of northern U.S. and western Europe, where it is strictly confined to the offshore waters of the coast. Audubon painted this illustration while he was in Boston, but his field acquaintance with the species was probably confined to his days in Labrador, where he saw king eiders but looked in vain for their nests. Actually, they proceed farther north and are widespread breeders through the islands of the Canadian Arctic. The king eider is somewhat more northern in distribution than the common eider, although at times the two might mingle in the same flocks.

The king eider is readily separated from the common eider at a distance on the water by its black back which vaguely suggests a black-backed gull; the back of the common eider is white. The facial profiles of the males are also quite different. The females are heavily barred, brown ducks that look very much alike except for the differences in profile and bill structure. These birds of the ocean often raft in large flocks, diving about the shoals for mussels and, when disturbed, flying in long strings low over the waves.

79. White-winged Scoter [Velvet Duck] i

Melanitta fusca [Fuligula Fusca]

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

(Courtship calls during head-throw display)

Rafts of scoters are a familiar sight along both coasts and, although the three species may occur in mixed flocks, this species may be picked out by the white wing-patches. These are seen readily in flight, even at a great distance, but on the water may be concealed unless the bird flaps its wings. Many migrate through the Great Lakes and a few may winter in deeper ice-free waters; but most proceed to the coast. The summer range is in the northwestern lake country from Hudson Bay westward through Canada and Alaska. There is some question as to its status as a breeding species in eastern Canada, east of Hudson Bay, although Audubon claimed that he found nests in Labrador.

Audubon did not think much of the bird’s edibility: “Their flesh is extremely dark, tastes of fish, and is very unpalatable, although I have seen persons of great judgment in matters of this kind not only eat it with avidity but praise it as highly as if it were equal to the most tender and juicy venison. They are sold in abundance in our eastern markets and those of the middle states at from fifteen cents to a dollar the pair.”

Melanitta perspicillata [Fuligula Perspicillata]

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

(Wing noise)

Riding the rough water beyond the breakers along our coasts during the winter months are great rafts of scoters. The surf scoter is separated readily from its associates, the white-winged and the black scoters, by its white head patches that have inspired the gunners’ nickname of “skunkhead coot.” It is the only one of the three that does not breed outside of Canada and Alaska, although a very few wander in winter to Britain and western Europe.

The pair in this portrait were painted by Audubon during his trip to Labrador in 1833. He knew these sea ducks well, having observed thousands in the Chesapeake, as well as off the coasts of New Jersey, New York, and elsewhere; but nowhere else had he seen the numbers that passed along the shores of Labrador: “For more than a week after we had anchored in the lovely harbor of Little Macatina, I had been anxiously searching for the nest of this species but in vain: the millions that sped along the shores had no regard for my wishes.” At length he did find a nest and the female at the right may have been the one he shot as it flushed from its eggs, the only nest he was able to find.

81. Black Scoter [American Scoter Duck] i

Melanitta nigra [Fuligula Americana]

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

(Whistle call)

Hunters once knew all three scoters as “coots,” and this species, solid black with a bright yellow or orange swelling on its bill, was known as the “butternose coot.” At times it mingles in flocks beyond the breakers with its relatives, the surf and white-winged scoters, but more often than not it is found in pure flocks of its own kind. It has a curiously disjunct breeding range in North America, nesting in Alaska and locally in northeastern Canada, but seemingly not in between. However, there are tens of thousands of lakes across northern Canada that have not been scrutinized by the eye of the ornithologist. The black scoter is better known in winter when it resorts to the coasts—on the Pacific side from Alaska to Oregon and on the Atlantic coast from the Gulf of St. Lawrence to the Carolinas and, rarely, to the Gulf states. There is also a Eurasian race that was once regarded as a distinct species. The status of scoters probably has not changed much since Audubon’s day. Their northern breeding grounds have not been subject to drainage and they are sought only by those bay-men who are hardy enough to withstand the scoters’ harsh environment.

Audubon did not say much about this species, but commented that “During their long stay along our shores, they congregate in vast multitudes, and being often shot on the wing, are sold in all the markets of our maritime cities, but their flesh has a strong fishy flavour, so as to be very unsavory.”

Oxyura jamaicensis [Fuligula Rubida]

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

(Belching during male bubbling display; Display flight)

Audubon was obviously pleased with his portrayal of the various plumages of the ruddy duck: “Look at this plate, reader, and tell me whether you ever saw a greater difference between young and old, or between male and female, than is apparent here. You see a fine old male in the livery of the breeding season, put on as it were especially for the purpose of pleasing the female. The female has never been figured before; nor, I believe, has any representation been given the young in the autumnal plumage. Besides these you have the young male at the approach of spring.”

Inasmuch as the natal home of the ruddy duck is in the marshy lake country of the prairies, it has been sorely affected by agricultural drainage. At times conservationists have been very much concerned about the stability of the ruddy, particularly after periods of drought, when special hunting regulations had to be imposed to prevent overkill of the diminished population.

Although it is a summer resident of the western prairies, it winters primarily along the eastern and western seaboards and across the southern states, often rafting in large numbers in favored bays. Audubon considered it abundant during the winter in Florida, “where I have shot upwards of forty in one morning. . . . I have found this species hard to kill and, when wounded, very tenacious of life, swimming and diving at times to the last gasp.” He regarded them as good eating when fat and young.

Lophodytes cucullatus [Mergus Cucullutus]

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

(Female flight call; Wing whistle; Male display)

This merganser is one of the most elegant of all North American ducks. The males, with their fan-like crests that they erect or compress at will, swim in small groups in the company of their bushy-headed, brown mates, preferring small secluded lakes and streams to the bigger, more open rivers frequented by many of the other waterfowl. During the summer the hooded merganser lays its eggs in hollow trees, much as the wood duck does, and, although it breeds widely in the eastern United States, it is so local and retiring that many birders scarcely suspect that it nests in their neighborhoods. Although it is common in the Great Lakes region during migration, it seldom winters there. It continues, rather, on to ice-free waters near the coast from Massachusetts south to Florida, as well as to inland streams from southern Illinois through the lower Mississippi Valley to the Gulf states.

Audubon often commented on the culinary aspects of ducks and other water birds. He did not rate the hooded merganser high: “Its flesh has a fishy taste and odor, although it is relished by some persons.” As an object of sport he found it not too accommodating: “The Hooded Merganser is the most expert diver and so vigilant that at times it escapes even from the best percussion gun. If you wound one, never follow it; the bird, when its strength is almost exhausted, immerses its body, raises the point of its bill above the surface, and in this manner makes its way among the plants until finding some safe retreat along the shore. Even on wing it is not easily shot. . . .”

Mergus albellus

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

Audubon, who could not resist taking Wilson to task for inaccuracies, wrote, “I have felt strong misgivings on reading Wilson’s article on this species and I cannot but think that he is mistaken when he states that ‘it is much more common on the coast of New England than further south,’ and again, ‘in the ponds of New England and some of the lakes in the state of New York where the few Smews are frequently observed.’ Now, although I have made diligent inquiry, I have not met with any person well acquainted with the birds of this family who has seen it. Wilson, in short, was in all probability misinformed and it is my opinion that figure was made from the stuffed specimen that was then at Peale’s Museum in Philadelphia and that he had taken the Buffleheaded Duck, seen at a distance, for this species.” Surprisingly, Audubon adds, “The only specimen procured by me was shot by myself on Lake Barataria not far from New Orleans in the winter of 1819. It was an adult female in fine plumage.” Although he “drew it on the spot,” his record has not been credited. However, this attractive merganser from the Old World has been carefully observed on at least three occasions in this century in eastern North America; once in Rhode Island, where it stayed for weeks, once in Ontario not far from Niagara Falls, and once in Quebec. At the other extremity of North America, in the western Aleutians, the smew is a rare overshoot from Asia.

85. Common Merganser [Goosander] i

Mergus merganser

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

(Alarm call; Alarm call)

In winter scores of mergansers often float on the tidal basin that serves as a reflecting pool for the Washington Monument and the Jefferson Memorial in the City of Washington. The stately white drakes, more than two feet long, with glossy green heads and bright carmine bills, accompany the bushy-headed, quaker-gray females. These birds, called goosanders in England, and also by Audubon, are the commonest ducks in winter on the rivers of the northern states, especially on the creeks that freeze partly over. There in the open stretches they dive in the swift current, taking care not to come up under the ice shelf. When they dive they often leap like porpoises and, submerging, outswim the small fish by using both feet and partly open wings. Unlike most other ducks, which have flat mud-straining bills, mergansers have spike-like bills with saw-toothed edges, perfect equipment for holding onto slippery fish.

In this print Audubon has shown a pair of these river-loving ducks in a typical merganser stream at Cohoes Falls in the State of New York. Mergansers spend the summer across the entire width of wooded Canada and make their appearance in the States when cold weather seals the northern ponds with ice. They are freshwater birds, seldom visiting tidewater except during severe freeze-ups. The red-breasted merganser (next plate) is the saltwater member of the family.

Mergus serrator

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

(Male display; Flight call)

This fish-eating duck with its wispy crest and spiky red bill is slimmer and more rakish than the common merganser, and it is not as white-looking at a distance on the water. The rusty-headed females of the two types are more difficult to tell apart. The red-breasted merganser is more addicted to large bodies of water, bays, and the outer coast than its relative, which is more likely to be found on rivers during the winter months.

Audubon reported that he had found parents in charge of their broods in Kentucky and also in parts of New York State and Massachusetts, where today one would certainly not look for this species during the nesting season. Its main breeding range in North America is farther north across Canada and Alaska. At the approach of the colder months these birds migrate to the coasts, some tarrying over winter on the Great Lakes. The species is also found widely across Europe and Asia.

The plants in this composition are a kind of pitcher plant known as “trumpets” (sarracenia), which Havell introduced when he made the engraving. These southern bog plants are completely inappropriate for this essentially saltwater duck. They were not in Audubon’s original watercolor.