SEABIRDS

Jaegers, Gulls, Terns, Skimmers, and Auks

Stercorarius pomarinus [Lestris Pomarina]

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Laridae

(Long call and other calls)

This, the largest of the three jaegers, nests, as do the other two species, in the tundras that surround the polar ocean. It is not likely to be seen by most birders unless they make pelagic voyages well offshore, for the home of the jaegers is the open sea. Only during stormy weather are they likely to be observed close to shore. Adult jaegers are distinguished by their two central tail feathers, which project well beyond the others. In this species these two feathers are blunt and twisted. Jaegers are both predators and scavengers. Indeed, they might be called “pirates,” because they harass gulls and terns, forcing them to disgorge their hard-earned fish.

Audubon never observed the pomarine jaeger along the shores of the United States. It was not until he made his journey to Labrador in 1832 that he became acquainted with it. He wrote, “While sailing towards the harbor of Little Macatina, and yet about forty miles distant from it, although not far from the shore, we observed a bird of this species approaching the vessel. It flew in the manner of the Pigeon Hawk, alighted on the water like a Gull, and fed on some codfish’s liver that had been thrown overboard for the purpose of attracting it. Several small Petrels joined it, but it did not come within shot, and the sea was too rough for even our whale boat. . . . On the 30th of July the young men of my party brought me a fine adult female in excellent order from which I drew the figure in the plate.”

187. Parasitic Jaeger [Richardson’s Jager]

Stercorarius parasiticus [Lestris Richardsonii]

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Laridae

(Call; Long call)

The British call all jaegers “skuas.” The American name “jaeger” is derived from a German word meaning “hunter,” and an early name used by residents of the colder coasts was “gull hunter.” Jaegers come in various light, intermediate, and dark phases, but all show a flash of white in the primary wing-feathers. When adult, this species can be identified readily by its pointed central tail feathers which project two or three inches beyond the rest of the tail. While in the Arctic, jaegers live on a diet of lemmings, eggs, and young birds; but at sea much of their food is taken from other seabirds, which they harass and rob, as well as any goodies that are available on the surface of the sea. Inasmuch as the winter range of jaegers is far offshore, little is known about their exact distribution during the colder months; but some parasitic jaegers range as far south as Tierra del Fuego off the southern tip of South America.

Audubon had little to say about this species. Nesting in the tundras of both the New World and the Old, it is the jaeger most likely to be seen inshore, and the one most likely to be encountered on the Great Lakes or elsewhere inland.

188. Long-tailed Jaeger [Arctic Jager]

Stercorarius longicaudus [Lestris Parasitica]

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Laridae

(Long call; Alarm calls at nest)

This, the smallest and most elegant of the three jaegers (or “skuas” as the British call them), with tail-streamers extending up to nine or ten inches, is the one least likely to be seen by birders using their binoculars from coastal points. Its journeys past the North American continent take it far out to sea where it may be spotted sometimes from transatlantic liners or, with luck, from a fishing boat, by those birders who make special trips well offshore. On the other hand, it is the jaeger most likely to be encountered during summer over much of the tundra in northern Canada and Alaska. Whereas the parasitic jaeger is rare but regular in migration on the Great Lakes and the pomarine somewhat scarcer, this species is very rare indeed at any point inland. All three jaegers are circumpolar, traveling from the Arctic to the oceans of the Southern Hemisphere. Audubon knew all three, but resorted largely to the writings of others when describing their habits during their summer sojourn in the far north.

After watching the tactics of this jaeger, forcing a gull to disgorge its fish, he wrote, “It is impossible for the Gull to escape, for the warrior, with repeated jerkings of his firm pinions, sweeps towards it with the rapidity of a Peregrine Falcon pursuing a Duck. . . . Its beautiful long tail-feathers seem at times to afford this bird great assistance in executing short sudden turns, which often brought to my mind the motions of a greyhound while pursuing a hare.”

189. Glaucous Gull [Burgomaster Gull] i

Larus hyperboreus [Larus Glaucus]

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Laridae

This ghostly gull, the size of a black-back, is the largest of the “white-winged” gulls, which lack black wingtips such as the herring gull exhibits. The unmarked “frosty” primaries, paler than the rest of the wing, give it a very similar appearance to the Iceland gull (see plate 190), which is smaller and more slender, about the size of a herring gull. When viewed at close range, which this wary gull seldom permits, it can be seen to have a narrow yellow (not red) eye-ring. Audubon saw plenty of Iceland gulls, especially on the New England coast, but somehow he missed the glaucous there, although he was told that it had not infrequently been taken at Boston and New York. He placed no reliance on such reports. However, this large predatory gull, that breeds on the rocky coasts that fringe the Arctic Ocean, does indeed venture south every year to the Great Lakes and the New England coast, and occasional birds have even reached the Gulf states.

Audubon did see a few on the coast of Labrador, all paired, in the month of July, 1832, but he reported that “our endeavors to discover their nests were unavailing, and their shyness, which surpassed even that of the Great Black-backed Gull, prevented us from seeing much of their habits.” The figures drawn here were from specimens presented to him by Captain James Clarke Ross, R.N., the intrepid Arctic explorer.

190. Iceland Gull [White-winged Silvery Gull] i

Larus glaucoides [Larus Leucopterus]

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Laridae

This pale, ghostly gull of the North lacks the black wingtips of the familiar herring gull, and can be confused only with its larger, heavier-billed relative, the glaucous gull, shown on the previous plate. Audubon, who obviously was quite familiar with the “White-winged Silvery Gull,” as he called it, wrote, “I have not met with this species farther south than the Bay of New York. During the winter it is not rare about Boston and farther eastward. At the approach of summer, before the pairing of the Herring Gull, Larus Argentatus, the White-winged Gulls collect in flocks, and set out for the distant north where they breed. . . . I was surprised to find but very few on the coast of Labrador and these did not seem to be breeding, for although we carefully watched them, we did not succeed in finding any nests.”

No one knew at that time that this bird bred in Greenland (not in Iceland); “Greenland gull” would have been a more appropriate name. A subspecies with gray markings in the wingtips, “Kumlien’s Gull,” breeds in Baffinland and is, in appearance, intermediate between the Iceland gull and the herring gull. Although the Iceland gull is mainly coastal during the winter months, sometimes patronizing the garbage dumps in the company of the more numerous herring gulls, a few move down the St. Lawrence River to Lake Ontario, Lake Erie, and, rarely, southern Lake Michigan.

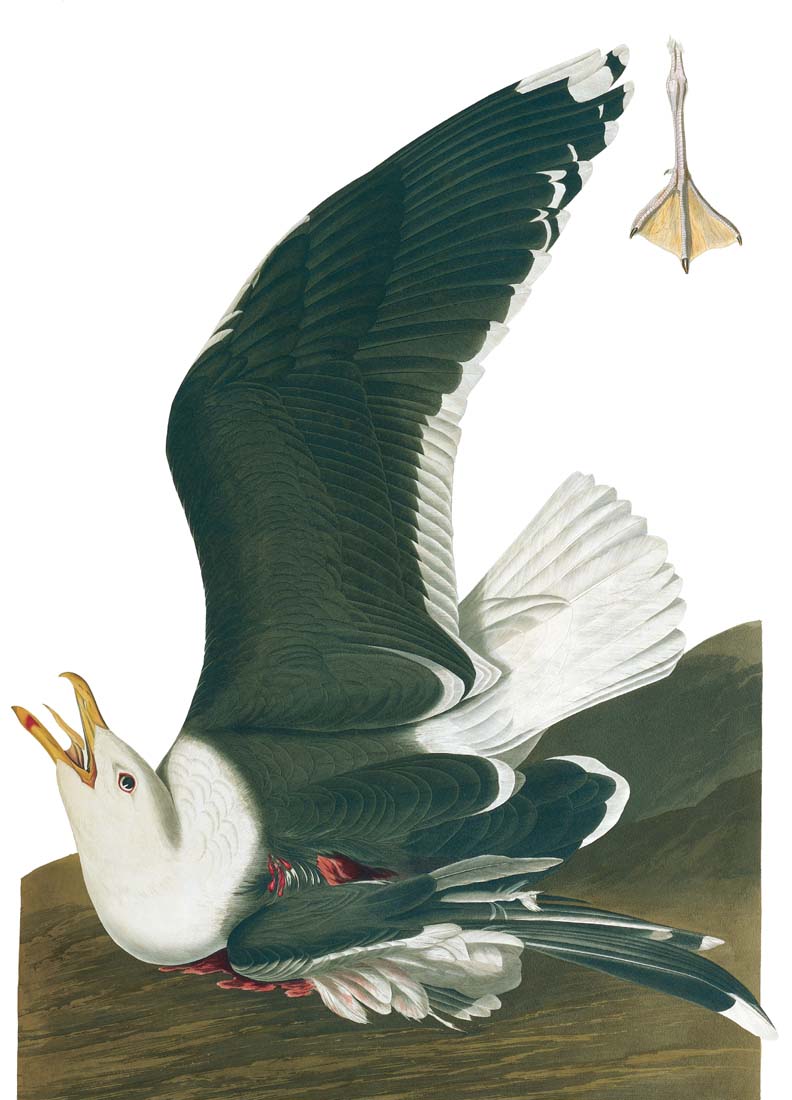

191. Great Black-backed Gull [Black-backed Gull] i

Larus marinus

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Laridae

(Call; Long call, calls)

The black-backed gull, like the herring gull, has benefited from man’s proliferation and his inevitable garbage dumps and sewer outlets. Whereas in Audubon’s day the black-back did not breed south of the eastern extremity of Maine, it has moved southward during the last fifty years until there are now thriving colonies the length of the New England coast and even outpost nestings as far south as Virginia and North Carolina. It is now a regular winter visitor to the Great Lakes, remaining to nest in two or three localities.

In addition to being a scavenger, the black-back is highly predatory. Colonies of puffins and terns, as well as lesser gulls, suffer because of its depredations. Audubon called it “the tyrant gull.” Dramatically he writes, “As he flies over each estuary, lake, or pool, the breeding birds prepare to defend their unfledged broods or insure their escape from the powerful beak of their remorseless spoiler. . . . Like all gluttons he loves variety and away he flies to some well known isle, where thousands of young birds or eggs are to be found. There, without remorse, he breaks the shells, swallows their contents, and begins literally to devour the helpless young. Neither the cries of the parents nor all their attempts to drive the plunderer away can induce him to desist until he has again satisfied his ever craving appetite.” In his painting, Audubon portrays a black-backed gull that has just been shot, prey to the artist’s own predatory impulses.

Larus argentatus

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Laridae

The herring gull, the best known “sea-gull,” has had a remarkable history of survival. From antiquity, the Indians on the Maine coast had robbed the gulls of their eggs and young, but it was not until their white successors invaded the coast that egging began to exhaust the colonies. This was already evident in Audubon’s day. He reported that at White Head Island in the Bay of Fundy he was surprised to see gulls nesting in fir trees. He was told by his host, Mr. Frankland, “When I first came here, many years ago, they all built their nests on the moss and in open ground; but as my sons and the fishermen collected most of their eggs for winter use, the old ones began to put their nests on the trees.” By 1900, because of additional pressure from the millinery trade, only about 9,000 pairs were left on the Maine coast. The Maine legislature and the National Audubon Society then initiated protection. The recovery, slow at first, accelerated after 1920. Winter survival was subsidized by the garbage dumps of growing cities. The exploding numbers of these opportunistic egg-eaters depressed the populations of terns and laughing gulls as new colonies extended inexorably down the coast. Even though the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, beginning in 1934, sterilized eggs to the number of a million or more, the herring gull now breeds as far south as Virginia and North Carolina, way beyond its former breeding range.

193. Ring-billed Gull [Common Gull] i

Larus delawarensis [Larus Canus]

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Laridae

This abundant gull, superficially like the herring gull, but smaller and more graceful, is readily separated from its larger look-alike by its yellow-green legs and the black ring that encircles its bill. There is no question that this well-made bird, like the herring gull, has increased vastly since the beginning of the century, when gulls, herons, shorebirds, and many others, then subject to gunning, reached their nadir, before a ground swell of public opinion demanded their protection. Although it no longer breeds at Eastport, Maine, and in several other northeastern localities where Audubon described thriving colonies, it seems to be doing extremely well in the Great Lakes area and to the Northwest. Its habits have changed too. Audubon stated that “the fisherman of Labrador and Newfoundland kill them in great numbers, and pack them in salt for winter use,” and that in general it “is so well acquainted with the artifices of man that it keeps, more than others, beyond the reach of the gun.” Today, on the beaches of Florida, it is great sport to feed them from the hand, and in a hundred other places up and down the coast they compete with the laughing gulls for tidbits offered by their human benefactors. More trusting than the herring gulls, they have learned to patronize restaurants and picnic grounds.

On Audubon’s colorplate he inscribed the name of the common or mew gull of Europe, Larus Canus, changing it later to “Common American Gull,” or “Ring-billed Mew Gull,” Larus zonorhynchus.

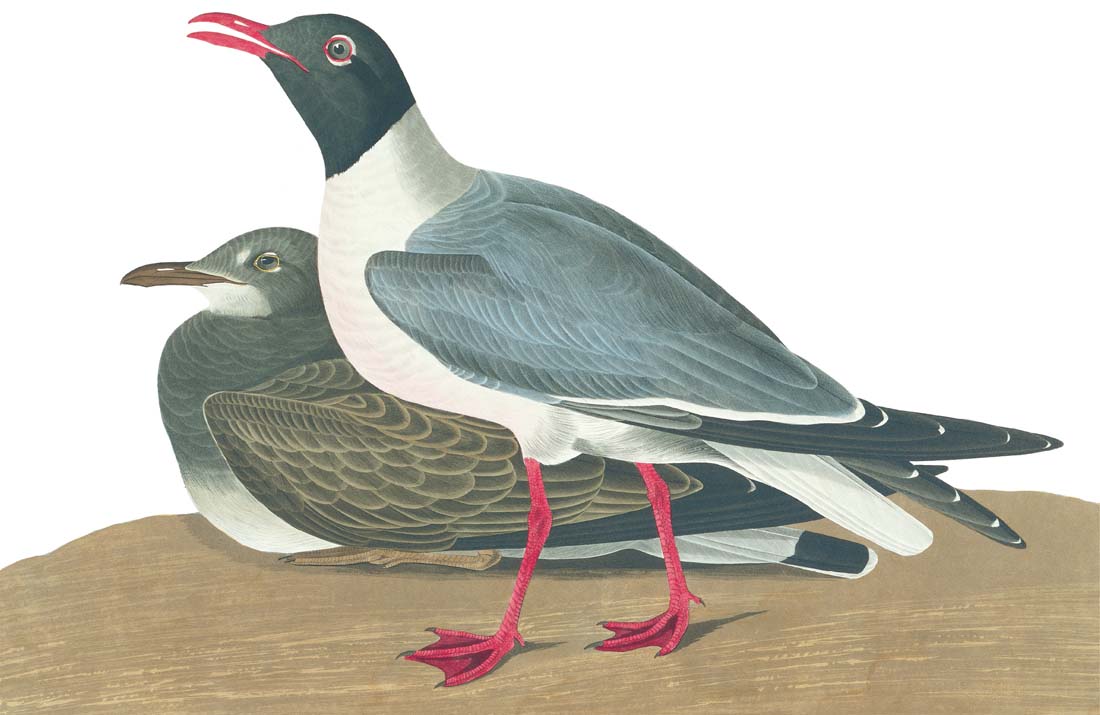

194. Laughing Gull [Black-headed Gull] i

Larus atricilla

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Laridae

The strident laughter of these small, dark-backed, black-headed gulls is the most pervasive sound on our southern beaches. These birds give great pleasure to the tourists who flock to Florida’s suncoast, performing aerial acrobatics for food tossed to them, even swooping to take bread held in the fingers. They are black-headed in the spring and summer only, and obscurely capped in winter, but they may always be distinguished from the ring-billed, Bonaparte’s, and herring gulls, with which they associate, by the darker mantle that blends into the black wing-tips.

Formerly, laughing gulls were heavily egged and shot; thus many colonies, such as those on Long Island Sound, which Audubon mentioned, ceased to exist. He wrote that on being shot, “the birds fall on the water and their companions plunge towards them, as if intent on rescuing them. This great sympathy often proves fatal to them, for if the gunner is inclined, he may shoot them down without any difficulty, and the more he kills the more his chances have increased.”

Although the legendary Linnaeus was the first formally to describe the laughing gull and give it the scientific name Larus atricilla, Wilson, who should have known this species well, confused it with the very different black-headed gull of Europe, listing it in his American Ornithology as Larus ridibundus. Audubon was quick to correct the scientific name, but kept the same vernacular name, “Black-headed Gull,” on the plate. Later in his text he added “or Laughing Gull.”

195. Bonaparte’s Gull [Bonapartian Gull] i

Larus philadelphia [Larus Bonapartii]

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Laridae

This petite, ternlike gull was described by George Ord from specimens taken on the Delaware River, near Philadelphia. He named it in honor of the nephew of Napoleon, Prince Charles-Lucien Bonaparte, a contemporary ornithologist who lived and worked in Philadelphia at the time. He gave it the scientific name Larus philadelphia, in recognition of the great city where he found the bird.

Audubon encountered his first Bonaparte’s gulls on the Ohio, near Cincinnati. After watching them for nearly half an hour, he shot one. He wrote, “On her dropping, her mate almost immediately alighted beside her, and was shot. There, side by side, as in life, so in death, floated the lovely birds.” Here again we glimpse the two faces of Audubon in conflict, the ruthless hunter and the sentimental man.

Later he saw Bonaparte’s gulls in greater numbers along the coast. In May, 1833, his son John “shot seventeen of them at a single discharge of his double barreled gun.”

These little gulls, which breed in wooded muskegs from James Bay across western Canada to central Alaska, place their nests in conifers, where they are safer from mammalian predators. In migration their flocks might appear on any sizeable body of water, where they can be identified at a distance by the wedge of white in the outer wing. Many winter on the Great Lakes, but the majority proceed to the saltwater bays, where they can be found on either coast, south of the Canadian border.

Pagophila eburnea [Larus Eburneus]

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Laridae

(Calls at colony)

This immaculate ternlike gull, which spends its year in the high Arctic, was unknown to Audubon, who drew his illustration from two specimens procured by Captain James Clark Ross during his expeditions in the far north. Dr. Richardson informed Audubon that they were observed breeding in great numbers on the high perforated cliffs that form the extremity of Cape Perry in the 70th degree of latitude. To this day few colonies are known because these gulls often resort to nunitaks and icebound cliffs some miles from the sea, as they do in Spitzbergen, north of Norway.

Normally, the ivory gull winters from the pack ice south to the Gulf of St. Lawrence. It also ranges along the arctic coasts of Europe and Asia. To see an ivory gull south of the Gulf of St. Lawrence is a red-letter event for the birder, but individuals are seen very rarely along the New England coast. They are accidental farther south and on the Great Lakes.

The ivory gull is the only all-white gull with black legs. Immature birds have a dusky smudge on the face, a sparse sprinkling of black spots above, and a narrow black border on the rear edge of the wing.

197. Black-legged Kittiwake [Kittiwake Gull] i

Rissa tridactyla [Larus Tridactylus]

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Laridae

This, the most oceanic gull, is circumpolar, breeding in swarming colonies on the slab-sided seacliffs of Alaska, Canada, Greenland, the British Isles, and Scandinavia. Kittiwakes shun the harbors and refuse heaps of human habitation and do most of their foraging at sea, where feeding frenzies in the distance look like confetti against the dark waves. At close range the black tips of their gray wings look as though “dipped in ink.”

Their nesting colonies, like those of razorbills and murres, are on cliffs so perpendicular, and ledges so narrow, that arctic foxes and other mammalian predators cannot reach them. This does not prevent them from being shot. Greenland Eskimos, using modern firearms, still decimate their ranks to feed their sledge-dogs. On the other hand, in Scotland and Norway, where people have long protected these dovelike birds, the colonies increased to the point where some adventurous kittiwakes have taken up residence on stone quarries, and even on the window-ledges of factory buildings. On our side of the Atlantic there is no colony south of the Gulf of St. Lawrence today, but Audubon reported that many bred on Grand Manan, off the Bay of Fundy. It may have bred even farther south; he wrote, “This species was so abundant on several islands off the Bay of Boston, that several basketfuls of them were procured in the course of a few excursions. When one fell to the water, the rest would hover around the boat, until many were shot from a flock.”

From left to right:

Calidris alba

(Conversational twittering and wik call; Pursuit flight calls; Conversational twittering by flock)

Sabine’s Gull [Fork-tailed Gull] i

Xema sabini [Larus Sabini]

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Laridae

Few birders have the pleasure of spotting this attractive fork-tailed gull off our eastern coast. Its journey to more southerly oceans carries it far offshore, and the destination of these Atlantic birds is a mystery. Audubon had the luck to see one flying over the harbor of Halifax in Nova Scotia in the company of ring-billed gulls. He was told by his friend, Thomas MacCulloch, that in the course of a voyage from Pictou in Nova Scotia to Hull in England, he saw great numbers of this species when more than a hundred miles off Newfoundland. They flew around the ship in the company of an almost equal number of Ross’ gulls. If true, it must have been an incredible sight, one that, to our knowledge, has not been duplicated since.

The species was discovered by the man whose name it bears, Captain Edward Sabine, who collected the first one on the west coast of Greenland, in the company of arctic terns. He later killed a pair in Spitzbergen. This circumpolar bird of the Arctic tundras breeds most commonly in Alaska, and travels off the Pacific coast to a wintering ground off Peru.

The sanderling (left), included in this colorplate, was intended to be shown with the others of its kind on plate 176, but being on another sheet of paper, was overlooked. So Havell, presumably with Audubon’s approval, combined it with the Sabine’s gull.

199. Gull-billed Tern [Marsh Tern] i

Gelochelidon nilotica [Sterna Anglica]

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Laridae

“Marsh Tern” was the name Alexander Wilson gave to this graceful bird he thought was a new species. Audubon was not convinced, so he took six specimens to the British Museum where he “minutely compared them in all their details with the specimens of the Gull-billed Tern which formed part of the collection of Colonel Montague and were procured in the south of England. I found them to agree so perfectly that no doubt remained with me of the identity of the bird loosely described by Wilson, with that first distinguished by the English ornithologist.” He added, “From what I know of the extraordinary power of flight of these birds, I am not at all surprised of it being found in Europe, any more than I should be to find it cosmopolitan.” Since Audubon penned those words the gull-billed tern has indeed proved to be cosmopolitan, wandering widely and breeding locally in many parts of the world. In the United States it breeds sporadically in small, scattered colonies in the coastal lowlands from New Jersey to Texas.

This was one of the last drawings (CCCCX) that Audubon was to put in the hands of Havell, the engraver, to complete the 435 plates in the Elephant Folio. When he opened his boxes it was missing. In near panic he wrote from London to John Bachman in Charleston: “Unless you find that Drawing at your House and send it to me immediately . . . it will come too late.” It came in time.

Clockwise from top center:

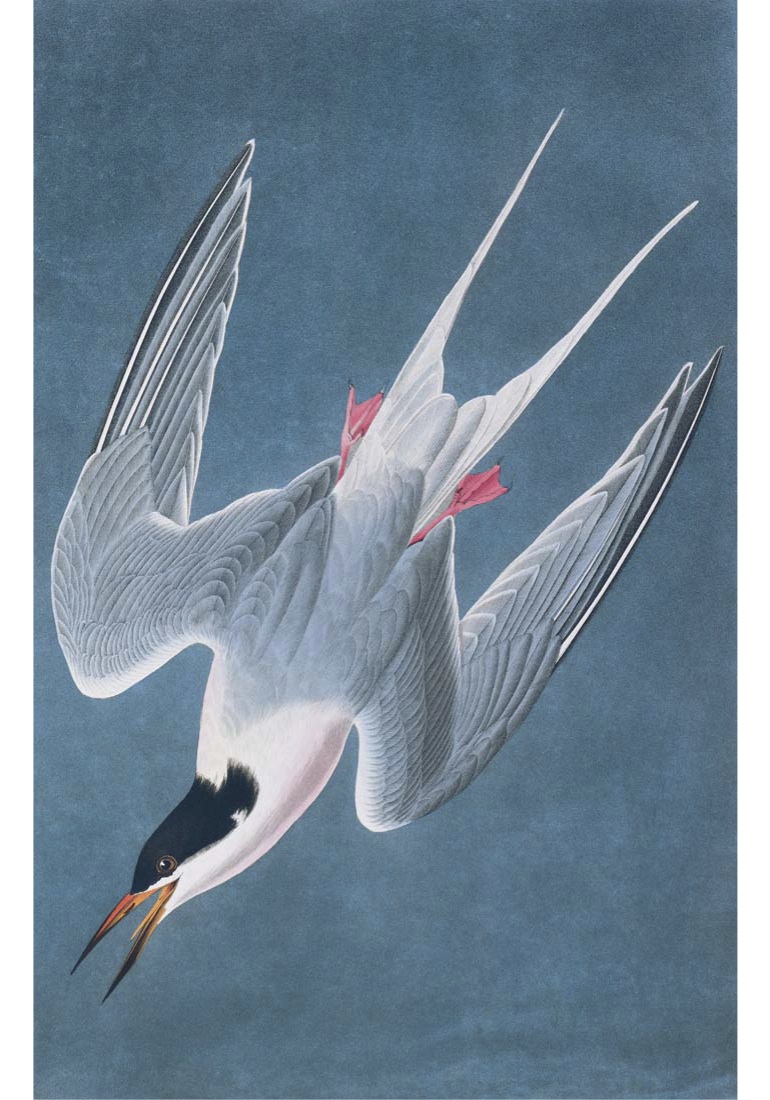

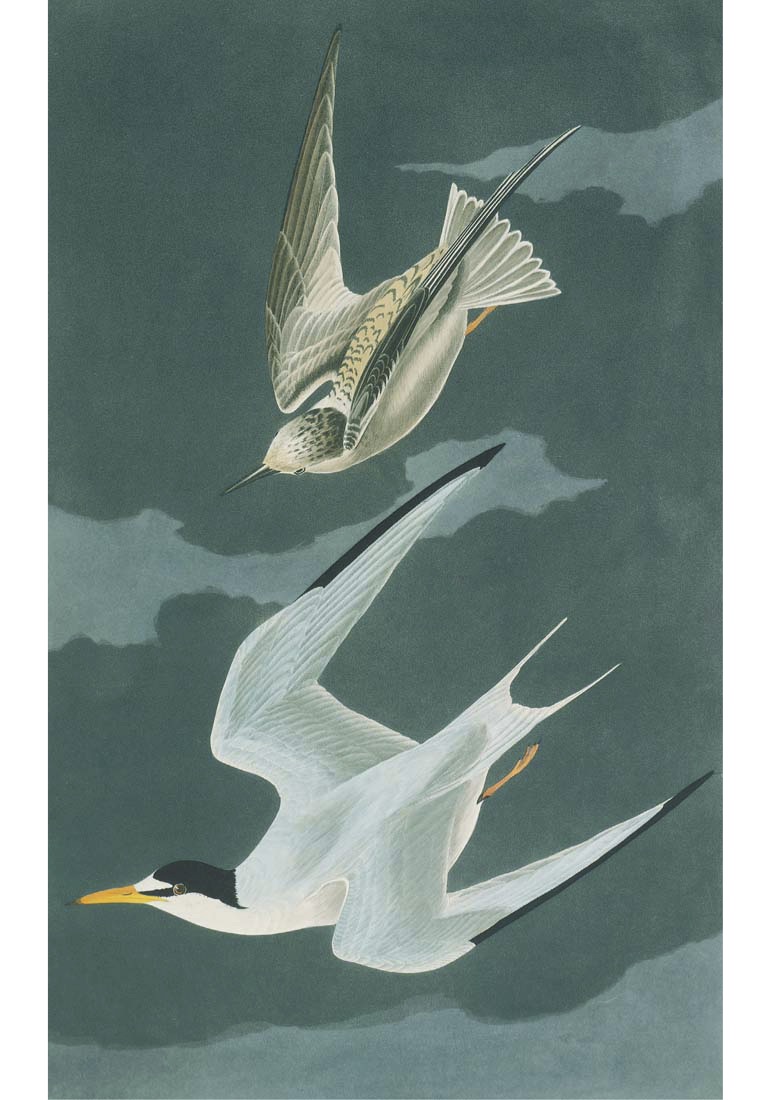

200. Forster’s Tern [Havell’s Tern] i

Sterna forsteri [Sterna Havellii]

(Calls)

Trudeau’s Tern

Sterna trudeaui

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Laridae

“Havell’s tern” (upper bird), which Audubon believed to be new, was in reality the winter plumage of Forster’s tern. Adult Forster’s terns and common terns are similar and it is evident that Audubon thought they were the same. Writing about the common tern, he spoke of “great numbers” breeding at Galveston Island, Texas. They were quite certainly Forster’s terns; the common tern does not breed south of North Carolina. This confusion of the adults is understandable. But the winter Forster’s is easily separated by the black mask through eye and ear. Audubon named this supposed nova avis in honor of Robert Havell.

Trudeau’s tern (lower bird) was described by Audubon on the basis of a specimen purportedly taken in New Jersey. His account is brief: “This beautiful Tern was procured at Great Egg Harbour in New Jersey by my esteemed and talented friend, J. Trudeau, Esq., of Louisiana, to whom I have great pleasure in dedicating it. Nothing is known as to its range, or even [its] particular habits. The individual obtained was in the company of a few others of the same kind. I have received from Mr. Trudeau an intimation of the occurrence of several individuals on Long Island.”

Inasmuch as no U.S. specimen of this South American tern is in existence, Mr. Trudeau’s assertions of “a few others” in New Jersey and “several individuals” on Long Island are suspect. The A.O.U. does not include this species in the official North American list.

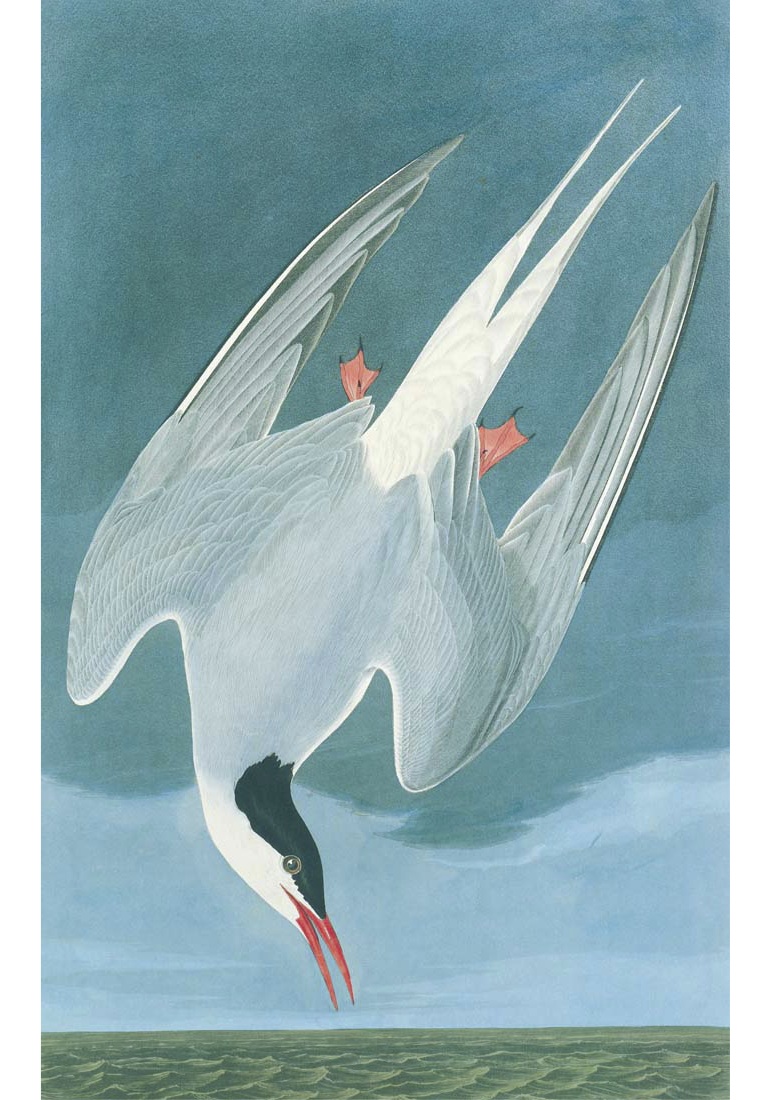

201. Common Tern [Great Tern] i

Sterna hirundo

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Laridae

“With an easy and buoyant flight, the Tern visits the whole of our indented coast . . . amidst all the comforts and enjoyments which kind nature has provided for it,” wrote Audubon. He went on: “Full of agreeable sensations, the mated pair glide along side by side, as gaily as ever a bridegroom and bride. The air is warm, the sky of purest azure, and in every nook the glittering fry tempts to satiate their appetite. Here, dancing in the sunshine, with noisy mirth, the vast congregation spreads over the sandy shores, where, from immemorial time, the species has taken up its temporary abode.”

The scene changed. It now has a darker side: The common tern, which once bred so widely along our coasts from North Carolina to Labrador and throughout the Great Lakes, has diminished sadly; many colonies have been abandoned. There are a number of causes for this decline: the destruction of its eggs by the growing gull population, the invasion of its nesting beaches by housing projects, and in some instances, chemical pollution.

The common tern ranges widely in both the New World and the Old, and is the most widespread of the terns or “sea swallows.” Charles-Lucien Bonaparte, however, regarded our American bird as distinct from the European form, and gave it the name “Wilson’s Tern.” Disagreeing, Audubon wrote, “I am of the opinion that no difference exists between the Common Terns of the two continents. The cry of both is precisely similar. . . . It seems to me improper to impose new names on objects, until it is proved by undeniable facts that they present permanent differences.”

Sterna paradisaea [Sterna Arctica]

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Laridae

The “long distance champion” amongst the world’s birds is by general consensus the arctic tern. It breeds as far north as any bird, on the barren tundras that fringe the Arctic Ocean, and it migrates southward over the trackless seas to its winter home in the Antarctic. In so doing it enjoys more hours of daylight during the course of the year than any other bird. The arctic tern is circumpolar, with a vast range in the colder seas of both the New World and the Old. Undoubtedly, it is sustaining its numbers far better than its more southerly counterpart, the common tern, which of late has been subjected to increasing gull predation, as well as attrition of its nesting beaches.

Audubon, like his colleagues, did not really know where the arctic tern spent the winter, but he wrote with assurance that it was found “along the coast of the Atlantic in autumn and winter, sometimes as far as New Jersey.” This was pure assumption. It is understandable why he had not encountered this species prior to his trip in the Maritimes to Labrador. The arctic tern does not go southward along our coast while en route to the Antarctic. Instead, it takes off across the Atlantic to the European side and thence southward off the African coast, eventually reaching the Weddell Sea.

Sterna dougallii

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Laridae

No bird of land or sea is more buoyant, more skillful in the air, than this exquisite tern. Gulls are clumsy by comparison. When Audubon saw his first roseate terns at Indian Key in Florida, he remarked: “I thought them the hummingbirds of the sea, so light and graceful were their movements.” Other writers since have made a more apt comparison, nicknaming them “sea swallows.”

Terns are among the world’s most cosmopolitan birds. They wander the seven seas at will, snatching tiny fish from the surface or diving for them like kingfishers. The different kinds look much alike, most of them being whitish with jet black caps and forked tails. This distinguished member of the clan, however, is more streamlined than the rest, with a longer tail and, in May, a soft peach-colored “bloom” on its breast.

The distribution of the roseate tern is strangely spotty. Found here and there along the Atlantic coast, the main group nests on certain little islands off southern New England and about Long Island Sound. To the south it is almost unknown but it appears again in the Florida Keys. The roseate tern also lives in Bermuda, Venezuela, on islands off the coasts of Europe and Africa, and farther east in India, Ceylon, and China. Hundreds of miles separate some of its colonies, to which the birds are drawn as if by magnets. Why they resort to certain ancestral bars and islands while unaccountably avoiding thousands of others that seem equally suitable is a mystifying habit.

Sterna fuscata [Sterna Fuliginosa]

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Laridae

(Calls at colony)

This black and white “sea swallow” of tropical oceans is undoubtedly the most numerous tern in the world. There are huge colonies in Hawaii, but except for occasional pairs in Louisiana and Texas, the sooty tern nests in only one spot near the continental United States: Bush Key in the Dry Tortugas, about 70 miles off Key West, where they have bred since time immemorial. Audubon vividly describes his visit there in May, 1832, when he was aboard the United States Revenue Cutter Marion: “On landing I felt for a moment as if the birds would raise me from the ground, so thick were they all around, and so quick the motion of their wings. . . .” On Bush Key he met a party of Cuban eggers from Havana. He wrote, “They had already laid in a cargo of about eight tons of the eggs of this [sooty] Tern and the Noddy. On asking them how many they supposed they had, they answered that they never counted them, but disposed of them at seventy-five cents per gallon.” A sooty tern’s egg weighs thirty grams, so that there are about fifteen eggs to the pound. Eight tons would come to nearly a quarter of a million eggs! Each bird lays only a single egg. If Audubon’s figures were correct, there must have been, since then, a spectacular decline, undoubtedly the work of the eggers. In 1903, there were only about 7,000 pairs of sooty terns. When the National Park Service took over, there were 15,000 nests. By 1950, the number had climbed to 95,000, but it has dropped by half since then.

205. Least Tern [Lesser Tern] i

Sterna antillarum [Sterna Minuta]

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Laridae

“Nothing can exceed the lightness of the flight of this bird,” Audubon wrote, “which seems to me to be among water-fowls, the analogue of the Hummingbird. Hovering on rapidly beating wings it spots its tiny finny prey and dives upon it with the quickness of thought.” Audubon inscribed it as the “Lesser Tern” on his colorplate but changed it to “Least Tern” in his texts, a name that persists now. This tiny tern, distinguished by its yellow bill, must have been much more wide-ranging than it is now, if we can credit Audubon’s statement that it “breeds from Galveston along the shores to Labrador. . . . Extremely abundant at times on the Great Lakes, as well as the Ohio and the Mississippi.” It still goes up the lower Mississippi and the Missouri, but barely enters the Ohio and is now accidental on the Great Lakes. Coastally, it does not breed north of Maine, and it is difficult to believe that Audubon found it “in abundance” in Labrador. There is no doubt that there has been a great decline, however. The least tern was nearly wiped out by the millinery trade around the turn of the century, but under protection it has made some recovery. In recent years, bathers and picnickers with their vehicles have made the bird’s reproduction impossible on many beaches. It seems to be surmounting this survival problem by establishing a number of colonies on the flat, gravelly roofs of supermarkets and shopping centers.

206. Royal Tern [Cayenne Tern] i

Sterna maxima [Sterna Cayana]

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Laridae

“On reaching the entrance to the little port of St. Augustine in East Florida,” Audubon wrote, “I observed more Cayenne [Royal] Terns together than I had ever before seen; . . . I found them at first in great flocks, composed of several hundred individuals, along with Razor-billed Shearwaters [Black Skimmers] which also congregated there in great numbers. . . . We shot as many as we wished, for as the flocks passed over any of the boats, several individuals were brought down at once, on which the rest would assail the gunners, as if determined to rescue their brethren.”

These large, crested terns of our southern seacoasts still range widely from Virginia to Texas and Mexico, but their known breeding places are few. By packing literally cheek to jowl in swarming colonies they survive predation by gulls and other enemies, but not human intrusion.

Audubon never painted the Caspian tern, a similar but larger species, nor did he give any intimation that he knew it. However, it is quite certain that the birds that he thought were “Cayenne” (royal) terns in Labrador and Newfoundland were, in fact, Caspian terns. He wrote, “My surprise at finding this species breeding in Labrador was increased by the circumstance of its being a rare occurrence at any season along the coast of our middle and eastern districts. Nor does it become abundant until we reach the shores of North Carolina, beyond which it increases the farther south you proceed.”

Today the name “Cayenne tern” belongs to a very similar species which occurs in South America.

Sterna sandvicensis [Sterna Cantiaea]

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Laridae

This rather large tern nests in dense colonies in the British Isles and elsewhere around the perimeter of middle Europe, where it was first described by Linnaeus’s protégé, Gmelin: but in North America it is relatively sparse in numbers. There may be scarcely more than a dozen colonies between Virginia and the coast of Texas, and these are sporadic, not always in the same place, but almost always with the more numerous royal terns.

Audubon was very excited on the 26th of May, 1832, while sailing along the Florida Keys, in Mr. Thruston’s barge, to observe a large flock of terns that he first thought were “marsh” (gull-billed) terns. He suspected from their manner of flight that they were different, a species unknown to him. “The pleasure which one feels on such an occasion cannot easily be described,” he wrote. No time was lost in collecting some. “The birds fell around us. . . . We continued to shoot until we procured a very considerable number. On examining the first individual picked up from the water, I perceived from the yellow point of its bill that it was different from any that I had previously seen, and accordingly shouted ‘A prize,’ ‘a prize.’ And so it was, good reader, for no person before had found the Sandwich Tern on any part of our coast.” He later visited a nearby nesting colony and reported that the eggs were capital eating. The wreckers, whom he questioned, often ransacked the colonies for the eggs of this bird as well as its young.

Chlidonias niger [Sterna Nigri]

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Laridae

This black-bodied tern is a bird of the marshes and inland lakes. During the early summer it breeds from the St. Lawrence River and the Great Lakes region westward across the southern provinces of Canada and the northern tier of states to the Pacific. Thus it was that Alexander Wilson, who lived near Philadelphia, had never seen a nest until he visited Louisville, Kentucky. When Audubon showed him some old nests on one of his favorite ponds, Wilson thought they belonged to “some species of Rail.” At that time the black tern was “abundant in the neighborhood, breeding on the margins of ponds at a short distance from the Ohio.” Its nests are usually placed on floating vegetation amongst water reeds or quite often atop muskrat houses.

By midsummer the black tern begins to molt and the black feathers of the head and body are invaded by white. By the time the young are on the wing and ready to travel they are little different from adults. Many of them migrate down the Mississippi Valley, but others go east or west to bays along the coasts. Their journeys take them eventually to South America. Black terns are also found in the marshes of Europe and Asia, whence they travel to Africa for the winter.

Anous stolidus [Sterna Stolida]

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Laridae

Whereas most terns are white or whitish with black caps, the noddy may be distinguished by its reverse coloration, being dusky with a whitish cap. Although it ranges widely in tropical oceans, the brown noddy nests on only one island off the continental United States: Bush Key in the Dry Tortugas, seventy miles off Key West in the Gulf of Mexico. The latest estimated count of noddies reported on this remote islet was about 7,000 pairs, a tenfold increase over the 700 pairs present thirty years earlier. Today they share Bush Key with the sooty terns, which numbered about 40,000 pairs in 1980. There is no competition between the two species for nesting space because the sooties always lay their eggs on the sand and the noddies off the ground, placing their nests of twigs and grass in the cacti and bushes. Although the noddies are definitely increasing, they are by no means as numerous as implied by Audubon. When he visited the Tortugas on the 9th of May, 1832, the noddies were nesting in a great colony of their own on Noddy Key. He wrote that as they approached the island, Captain Robert Day of the Revenue Cutter Marion assured him that “both species were on their respective breeding grounds by millions,” surely an exaggeration. Later in his account of the noddy Audubon reiterated: “Breeds in vast multitudes on the Tortugas Keys.” Because of commercial egging they were brought almost to the point of no return by the early 1900s, the zero years for so much of our wildlife.

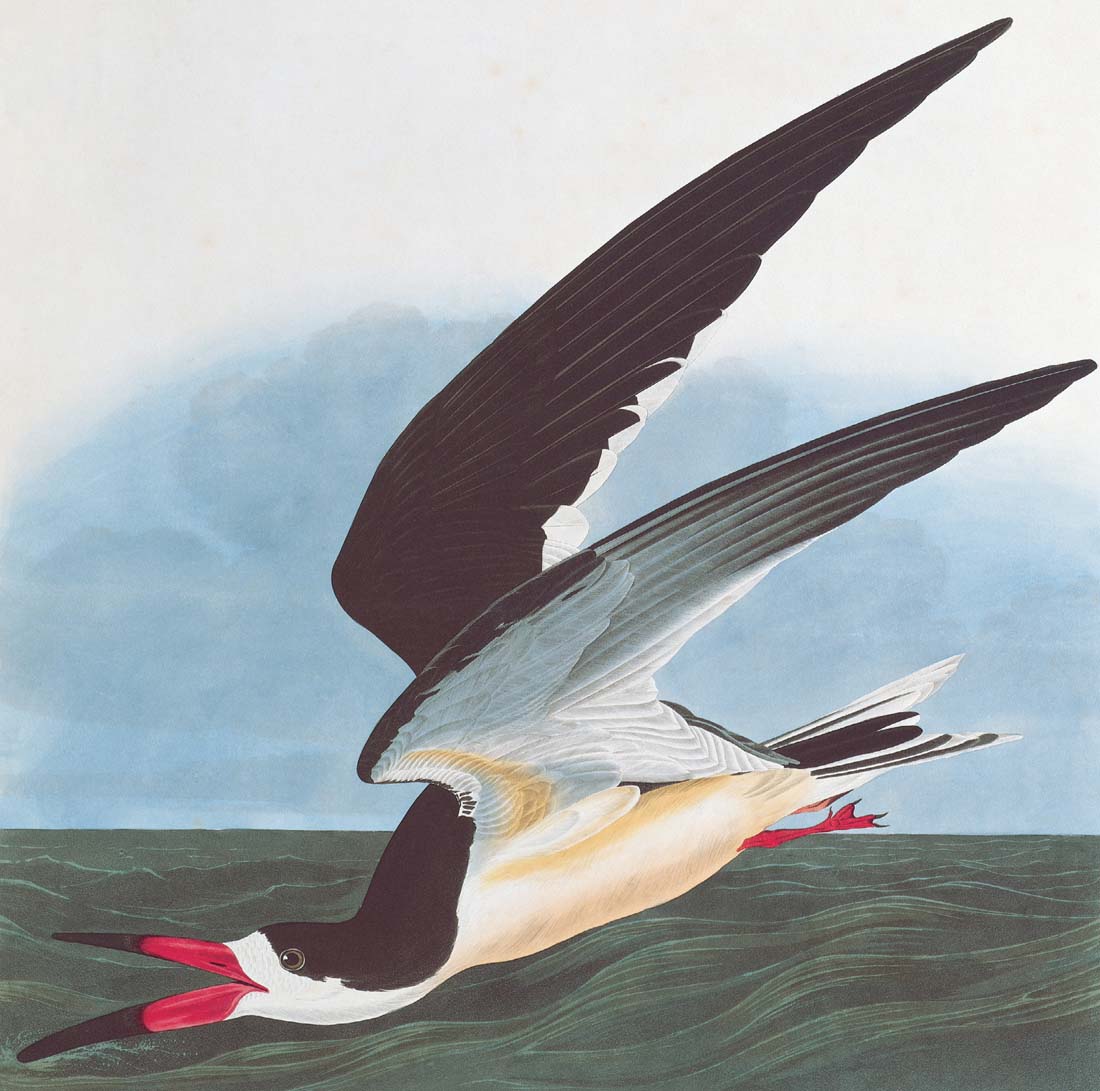

210. Black Skimmer [Black Skimmer or Shearwater] i

Rynchops niger [Rhincops Nigra]

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Laridae

Skimming the coastal bays from Cape Cod to Texas and from there to South America, the black skimmer or “Razor-billed Shearwater,’’ as Audubon called it, is unique among American birds in having the lower mandible a third longer than the upper. The flat, blade-like lower mandible of the open bill cleaves the water like a bloody knife as the bird skims along, barely an inch or two above the smooth water. If it touches a fish or some other edible morsel, a trigger mechanism quickly closes the upper mandible over the lower.

“I think I can safely venture to say,” Audubon wrote, “I have seen not fewer than ten thousand of these birds in a single flock.” The Reverend John Bachman inserted a note in Audubon’s journal that at Bull’s Island in South Carolina “probably twenty thousand nests were seen at a time. The sailors collected an enormous number of their eggs.” Alexander Sprunt, Jr., reported that not so many years ago skimmers’ eggs were still being sold in the streets of Charleston by hawkers who shouted “Loon aigs! Loon aigs!”

By the early part of this century skimmers no longer bred as far north as Long Island, but during the mid-1930s they reappeared and nested on the spoilbanks thrown up by dredges in the ship channels. Skimmers now nest locally the entire length of Long Island, and there are even a few as far northeast as Cape Cod.

Pinguinus impennis [Alca Impennis]

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Alcidae

The original “penguin,” the great auk, was the first North American bird to become extinct in historic times. This flightless seabird was still in existence when Audubon painted this portrait from a specimen in London, about 1835, but he never saw the bird in life. He wrote, “The only authentic account of the occurrence of this bird on our coast that I possess, was obtained from Mr. Henry Havell, brother of my engraver, who, when on his passage from New York to England, hooked a Great Auk on the banks of Newfoundland in extremely boistrous weather. On being hauled on board, it was left at liberty on the deck. It walked very awkwardly, often tumbling over, bit everyone within reach of its powerful bill and refused food of all kinds. After continuing several days on board it was restored to its proper element.” He added, “When I was in Labrador many of the fishermen assured me that the ‘penguin’ as they named this bird, breeds on a low rocky island to the southeast of Newfoundland [probably Funk Island], where they destroy great numbers of the young for bait. . . . In Newfoundland, I received similar information from several individuals. An old gunner residing on Chelsea Beach near Boston told me that he well remembered the time when the penguins were plentiful about Nahant.”

The last great auks in North America were destroyed on Funk Island, Newfoundland, about 1841, and the very last in the world (a pair) were killed on Eldey Rock in Iceland on June 3, 1844.

Alca torda

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Alcidae

The razorbill, a seabird the size of a small duck, is like a miniature of the great auk, now extinct; but unlike its larger relative, it never lost the ability to fly, and so was able to escape the clubs of marauding fishermen, though not their guns. Audubon describes such a foray in the Gulf of St. Lawrence:

“We landed on a small rugged island. Our men were provided with long poles having hooks at their extremities. These sticks were introduced into deep and narrow fissures from which we carefully drew out the birds and eggs. As the birds, afrighted, flew hurriedly past us by hundreds, many of their eggs were smashed. The farther we advanced the more dismal did the cries of the birds sound in our ears, many of them despairing of affecting their escape, crept into the surrounding recesses. Rare fun to the tars, in fact, was ever such trip, and, when we joined them, they had a pile of auks on the rocks near them. The birds flew directly toward the muzzles of the guns, and we therefore needed little dexterity to shoot them.”

Unlike the great auk, the razorbill survived these savage forays and today can still be found on many rocky islands and headlands from Labrador south to the coast of Maine. In the winter, a few razorbills progress south to Long Island and New Jersey, and occasionally farther. There has been some diminution in numbers in recent years, presumably because of oil spills at sea.

213. Common Murre [Foolish Guillemot] i

Uria aalge [Uria Troile]

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Alcidae

(Colony)

There are no penguins in the Northern Hemisphere, but they have their counterparts in the murres and other auks which parallel them ecologically. The teeming colonies of murres (or guillemots as they are known in Britain) are suggestive of the vast aggregations of penguins in the Southern Ocean. The main difference is one of plane or dimension, since their nurseries are usually vertical rather than horizontal. The two species of murres enjoy by far the widest distribution of all the auk family, breeding by the million on the rocky seacoasts of both the North Atlantic and North Pacific.

Today murres do not nest south of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, but Audubon wrote, “A very old gunner whom I employed while at Boston, during the winter of 1832–33, assured me, that when he was a young man, this species bred on many of the rocky islands about the mouth of the bay there; but that for about twenty years back none remained after the first days of April.”

Murres were heavily egged, and Audubon reported that “whilst at anchor at Great Macatina, one of our boats was sent for eggs. . . . ere many hours had elapsed, the boat was again alongside with two thousand five hundred eggs.” He added that “they are collected in astonishing quantities by the ‘eggers’ and sent to distant markets, where they are sold at from one to three cents each.” Today the murre’s greatest threat is not egging but oil spills at sea.

214. Thick-billed Murre [Large-billed Guillemot] i

Uria lomvia [Uria Brunnichii]

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Alcidae

(Calls [including laugh and crow]; Crow, growl, and nod calls)

The two murres enjoy by far the widest distribution of all the auk family. There are millions in the polar basin, mostly thick-bills, which were formerly called “Brunnich’s murres.” Leslie Tuck of Newfoundland, who devoted years of research to the murres, estimated a total population of some 56 million, with the thick-billed, the more northern species, predominating three to one. He stated, “I do not think that the world population can be less than 50 million. I do not think it exceeds 100 million.” He was of the opinion that the thick-billed murre (with a population of 40 million) might well be the most abundant seabird in the world.

Although some thick-billed murres nest as far south as the Gulf of St. Lawrence, mixed in with the more numerous common murres, the majority breed much farther north. Audubon apparently did not make the acquaintance of this species during his trip to Labrador. He wrote, “I have never observed this bird on any part of the coast of our middle districts and, although I was told that it not infrequently occurred about the Bay of Boston, I failed to procure it there. . . . The specimen from which my figure was made was sent to me on ice, along with several other rare birds from Eastport in Maine. . . .”

Alle alle [Uria Alle]

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Alcidae

(Colony)

This, the smallest resident seabird in the North Atlantic, and by far the smallest winter seabird, exists by millions along the coasts of northern Greenland, with outpost colonies in northern Ireland, Spitzbergen, and elsewhere. Dovekies winter well offshore in the North Atlantic, from the iceline south to New Jersey. Beyond this they are seldom seen by birders unless “wrecked” by November storms. During a strong gale they may be driven as far south as Florida, or even inland, unable to fight the fierce winds.

Dovekies, called “little auks” in Britain, are readily recognized by their contrasting pattern, black above and white below. They have a stubbier bill than that of the larger auks. In Greenland seas, near the breeding grounds, their flocks bunch tightly and rise in swarms at the approach of a ship, and drift away like great clouds of mosquitoes. Audubon, who also used the names “Sea-Dove” and “Little Guillemot” for these birds, thought “how easy it would be to catch these tiny wanderers of the ocean with nets thrown expertly from the bow of a boat, for they manifest very little apprehension of danger from the proximity of one, insomuch that I have seen several killed with the oars.”

Dovekies are the first small birds to appear in the spring in the far North. They are hailed by the Eskimos, who kill them by the thousands and literally eat the warm and bleeding creatures out of their skins. Their eggs are placed under the rubble of stony skrees beneath great cliffs that rise from the sea.

Cepphus grylle [Uria Grylle]

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Alcidae

(Whistles; Alarm scream)

Unlike the other auks that live around the rocky coasts of the North Atlantic, the black guillemot does not gather in large colonies but is usually found in smaller groups of a dozen or fewer. It produces two spotted white eggs which are hidden in rocky crevices or under piles of boulders and broken rocks. Because of this difficulty of access, this species was not as vulnerable to the eggers as the other auks.

When a boat approaches, the birds standing guard on the rocks near their nest sites take off, revealing large white wing patches, and when they veer to make a landing on the water, they spread their bright red feet.

The black guillemot ranges along our Atlantic coast from the Arctic islands south to coastal New Hampshire and also down the east flank of Hudson Bay to James Bay. Most birds spend the winter offshore not far from their breeding grounds, but a few wander southward to Massachusetts and, very rarely, to the offshore waters of New Jersey. At that season the bird becomes whitish but the wings remain black with white patches as in summer.

Audubon wrote, “During severe winters I have seen the Black Guillemot playing over the waters as far south as the shores of Maryland. Such excursions, however, are of rare occurrence and it is seldom that any of these birds are to be seen until you reach the Bay of Boston.”

217. Marbled Murrelet [Slender-billed Guillemot] i

Brachyramphus marmoratus [Uria Townsendi]

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Alcidae

(Keer calls; Keer and groan calls; Kee and keer calls at sea)

The marbled murrelet was the mystery bird of the Northwest for the greater part of two centuries. Although it is common enough along the coast from southeastern Alaska to northern California, it was the last North American bird to reveal the secret of its nest. Its summer range, which coincides closely with the coastal conifer forests, should have been a clue, but inasmuch as all other auks nest on the ground, either on rocks or in burrows, ornithologists assumed that this species probably nested in burrows somewhere in the forest.

In 1970, the editors of Audubon Field Notes offered one hundred dollars for proof of an actual nest. On August 7, 1974, Hoyt Foster, a tree surgeon, was in the Santa Cruz Mountains of California trimming branches from a Douglas fir above a campsite. On a dead limb nearly 150 feet above the ground was a murrelet chick. A mystery that had baffled ornithologists for 185 years was solved. However, Russian ornithologists reported that a nest of the Siberian subspecies had been discovered in a larch in 1961.

The marbled murrelet wears its brown plumage, aberrant for an auk, during the spring and summer months. During the winter it looks more like some of the other small auks, blackish above and white below. Audubon, never having met this bird, thought the difference in plumages was sexual rather than seasonal. Therefore he labeled the brown bird a female and the black and white one a male.

218. Atlantic Puffin [Puffin] i

Fratercula arctica [Mormon Arcticus]

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Alcidae

This “sea parrot,” as it was often called in Audubon’s day, is believed by some marine biologists to be one of the most abundant seabirds in the North Atlantic. It is estimated that somewhere between ten and sixteen million nest on the sea-cliffs around Iceland alone. It also breeds in great numbers on certain rocks off the coasts of Newfoundland and Labrador. Audubon described a visit to Perroket Island in Labrador where “one might have imagined half the Puffins in the world had assembled.” Going south, the colonies shrink until in Maine they are found nesting in only two places.

The National Audubon Society, under the direction of Stephen Kress, has been attempting to reestablish puffins on Eastern Egg Rock in Muscongus Bay in Maine. Young flown in from Newfoundland are hand-reared on the island, and it is hoped that once they have fledged and flown they will eventually return to the island of their nativity to breed. To encourage the returnees, lifelike wooden decoys are set out on the rocks to lure them. The chief predator around puffin colonies is the great black-backed gull, which takes even the adults. This gull has extended its range southward in recent years and, like the herring gull, is now much more numerous and therefore more of a threat. Puffins have suffered a serious decline in the British Isles near the southern extremities of their Old World range for reasons that are not clear. They have probably had a similar decline on the Canadian side, but this is not well documented. Iceland is their main metropolis.

219. Horned Puffin [Large-billed Puffin] i

Fratercula corniculata [Mormon Glacialis]

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Alcidae

The auks and puffins which take the place of penguins in the cold northern oceans reach their most varied expression in the Bering Sea. Two species of puffins live there: the tufted puffin (plate 220), with its long golden locks, and this species, the horned puffin. Superficially, the horned puffin looks very much like its North Atlantic counterpart, but it has a much yellower beak and a peculiar erectile horn above each eye. Whereas the tufted puffin nests in the turf on the rocky coastal islands, the horned puffin lays its eggs far back under the loose jumbles of boulders.

Audubon did not know exactly where this species lived but presumed he had seen it on “the outer side of the island of Grand Manan, at the entrance of the Bay of Fundy.” Equivocally he added, “Even then I rather supposed than was actually certain that the birds observed were Large-billed Puffins.” It is, of course, the Atlantic puffin that is numerous around Grand Manan. Audubon’s friend Prince Charles-Lucien Bonaparte also erred when he stated that “this species is not uncommon in winter on our coast.” The actual specimens from which Audubon drew his plate were loaned to him by Mr. Gould, the great bird artist of London, and certainly must have come from the North Pacific.

220. Tufted Puffin [Tufted Auk] i

Fratercula cirrhata [Mormon Cirrhatus]

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Alcidae

(Adult call, chick call)

This bizarrely beautiful alcid ranges the rocky coasts of the North Pacific, yet its appearance in the Atlantic would be purely accidental. Audubon’s record remains unique to this day: “The specimen from which I drew the figure of this singular looking bird, was procured at the mouth of the Kennebec River in Maine. It was shot by a fisherman gunner, while standing on some floating ice, in the winter of 1831–32. No other individual was seen. I could not obtain any information respecting its habits; but as the bird was in tolerable order, I hope that my figures of it will prove not unacceptable. It was a male, and appeared to be adult.”

Tufted puffins range widely on both sides of the Pacific, from the Bering Sea and the Arctic coast of eastern Siberia south to Japan’s northernmost island, Hokkaido, where there is a small colony. On the American side they are numerous in coastal Alaska, throughout the Aleutian chain, and south locally to the Santa Barbara Islands off the coast of California. Fish are their main diet; and some do not hesitate to remove the bait from an angler’s hook if they have the chance. The golden plumes and huge yellow bill may have something to do with courtship; these are much reduced in winter.

From left to right:

Ancient Murrelet [Black-throated Guillemot] i

Synthliboramphus antiquus [Mergulus Antiquus]

(Chirrup call)

Marbled Murrelet [Black-throated Guillemot—young] i

Brachyramphus marmoratus [Mergulus Antiquus]

(Keer calls; Keer and groan calls; Kee and keer calls at sea)

Least Auklet [Nobbed-billed Phaleris]

Aethia pusilla [Phalerus Superciliata]

Crested Auklet [Curled-crested Phaleris]

Aethia cristatella [Phaleris Cristatella]

(Cackle; Trumpet)

Rhinoceros Auklet [Horned-billed Guillemot] i

Cerorhinca monocerata [Ceratorrhina Occidentalis]

(Mooing with clucks)

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Alcidae

Of the twenty-two species of auks or “alcids” in the world, seventeen live in the North Pacific. Inasmuch as Audubon’s journeys did not take him to the West Coast, he never met with any of the seabirds on this composite plate, which depicts five species (he recognized four). He identified the two birds at the left as ancient murrelets (“Black-throated Guillemots”), adult and young. Actually the bird in the rear is a marbled murrelet (see plate 217). The small bird swimming in the center is a least auklet, the swimming bird at the right is a crested auklet, and the larger standing bird is the rhinoceros auklet.

All of these birds were probably drawn separately in London from museum mounts or specimens forwarded to Audubon by Dr. Townsend. When they were engraved, they were rearranged; the position of the crested auklet was reversed and an arctic background was furnished. Later Audubon repeated the “four” species on individual plates in his smaller octavo edition of Birds of America.