SHOWY BIRDS, NOCTURNAL HUNTERS, AND SUPERB AERIALISTS

Pigeons, Parrots, Cuckoos, Owls, Nightjars, Swifts, and Hummingbirds

Columba leucocephala

Order: Columbiformes

Family: Columbidae

(Song; Call; Wing clap)

Some of Audubon’s finest compositions were painted during his stay in the Florida Keys, where he noted pigeons and doves of a half dozen sorts. In those days they were shot and their nests pillaged until two species, the Zenaida dove and the Key West quail dove, no longer came to the Keys from the West Indies. However, the white-crowned pigeon still makes the annual crossing from Cuba to nest in the mangroves and feed on the sea grapes that grow in the Keys. The stronghold of this large pigeon is in the West Indies, but it can also be found locally on Cozumel and other Caribbean islands off the coast of the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico.

Undoubtedly, the white-crowned pigeon owes its survival to its excessive shyness which Audubon noted when he tried to shoot some to use as models. Even so, he succeeded all too well, shooting thirty-six one day and seventeen more the following morning. He reported that they arrived from across the Gulf Stream during the latter part of April. He watched several as they approached the shore, skimming low over the water, then rising to survey the country before pitching into the deepest recesses of the mangroves, where he found it difficult to hunt them. Many years later, the great conservation society that bears his name gave warden protection to the diminished stock of this attractive pigeon.

Columba fasciata

Order: Columbiformes

Family: Columbidae

(Song; Grunts)

This stocky pigeon, slightly larger than a domestic pigeon or rock dove, is a resident of the western pine-oak forests that range from British Columbia to the mountains of Nicaragua. Inasmuch as it lays but a single egg, it could have gone the way of the passenger pigeon had it not been for its less gregarious habits and the remote forest in which it lives. With the lowest reproductive rate of any North American gamebird, it is still hunted, but under strict governmental regulations which have allowed a good recovery since the low point its population level reached during the early years of this century. Audubon, who never knew this bird in life, received several specimens from Dr. Townsend, who also furnished him with an account of its habits, as did Mr. Nuttall.

Botanically, this plate is particularly interesting because it depicted, for the first time, a new species of plant, the western or mountain dogwood, Cornus nuttalli. Audubon wrote: “In my plate are represented two adult birds, placed on the branch of a superb species of dogwood, discovered by my learned friend, Thomas Nuttall, Esq., when on his march toward the shores of the Pacific Ocean, and which I have graced with his name!” The branch, with its leaves and flowers, was painted by Maria Martin. Seeds of this new species were sent by Audubon to Lord Ravensworth, near London, to plant on his estate.

Zenaida aurita [Columba Zenaida]

Order: Columbiformes

Family: Columbidae

(Song)

To find this rather plain dove, so much like the mourning dove except for its square-tipped tail, one must now go to the West Indies, or the tip of the Yucatan Peninsula. It would be purely accidental today in the Florida Keys, where Audubon found it common. Indeed, it was so numerous in his time that he was able to shoot nineteen in the space of one hour.

He wrote, “The Zenaida Dove is a transient visitor of the Keys of East Florida. Some of the fishermen think that it may be met with there at all seasons, but my observations induce me to assert the contrary. It appears in the islands near Indian Key about the 15th of April, continues to increase in numbers until the month of October, and then returns to the West India Islands, whence it originally came. They begin to lay their eggs about the 1st of May. . . . Those Keys which have their interior covered with grass and low shrubs and are girt by a hedge of mangroves, or other trees of inferior height, are selected by them for breeding; and as there are but few of this description these places of resort are well known, and are called Pigeon or ‘Dove Keys.’” He wrote that in the morning and evening they came to drink at “certain wells, which are said to have been dug by pirates.” He added, “Heard in the wildest solitudes [their] notes never fail to remind one that he is in the presence and under the protection of the Almighty Creator.”

225. Mourning Dove [Carolina Turtle Dove or Carolina Pigeon] i

Zenaida macroura [Columba Carolinensis]

Order: Columbiformes

Family: Columbidae

(Song)

Describing this flowery scene in flowery words, Audubon wrote: “On the branch above, a love scene is just commencing. The female, still coy and undetermined, seems doubtful of the truth of her lover, and virgin-like, resolves to put his sincerity to the test, by delaying the gratification of his wishes. She has reached the extremity of the branch, her wings and tail already opening, and she will fly off to some more sequestered spot, where, if her lover should follow with the same assiduous devotion, they will doubtless become as blessed as the pair beneath them.”

Nature writers of an earlier generation often wrote in this vein, seeing human thoughts and emotions mirrored in wild creatures. Birds became little people dressed in feathers. “Humanizing” the animals made them more appealing, but it distorted truth and retarded the understanding of wildlife. Although some of the same natural laws control both birds and men, modern behaviorists find that birds have a psychology of their own, quite unlike ours.

The mourning dove, or “Carolina turtle dove,” as it was called in Audubon’s day, is found from coast to coast. Heavily hunted in some states, it is protected in others, as in the New England states, where it has increased in recent years. It now winters farther north because of the prevalence of bird feeders.

Ectopistes migratorius [Columba Migratoria]

Order: Columbiformes

Family: Columbidae

Over a century ago the passenger pigeon was probably the most numerous bird in the world; today it is extinct. Incredible as it seems, it may have outnumbered all other birds in the United States combined—hundreds of species. One authority, summing up the evidence, believes that in Audubon’s day there were nearly five billion passenger pigeons in the states of Kentucky, Ohio, and Indiana alone! From Newfoundland to Florida, early writers told of immense hordes. The great columns in flight, extending for hundreds of miles, blotted out the sun and took as much as three days to pass. Audubon estimated a flock near Louisville at 1,115,136,000 birds. Alexander Wilson estimated an even larger flock in Kentucky to contain 2,230,272,000 birds. He considered this far below their actual numbers. He reckoned that if each bird ate a half pint of acorns a day, their daily food consumption would be 17,424,000 bushels! This single, massive flock would have outnumbered, ten to one, all birds in the British Isles as once estimated by James Fisher.

Accounts of the great roosts read like the tales of a romancer. Trees broke under the weight of the pigeons; thousands of armed men slaughtered them day and night and shipped countless barrels to the big cities, where they rotted on the sidewalks for want of buyers. The last immense nesting took place in Michigan in 1878. During the next thirty years the remaining flocks dwindled until they were gone. The last passenger pigeon in the world expired at the Cincinnati Zoo at 1:00 P.M. Central Standard Time, September 1, 1914.

227. Common Ground Dove [Ground Dove] i

Columbina passerina [Columba Passerina]

Order: Columbiformes

Family: Columbidae

(Song)

The little ground dove, scarcely larger than a sparrow, flushing from the weeds along the roadside, displays its rufous wings and a stubby black tail. It is a familiar dooryard bird in the southern states, from the lowlands of the Carolinas and California southward to Costa Rica, as well as in northern South America.

Audubon wrote that he had often found these small doves “in the inner court of the famous Spanish fort of St. Augustine. They are easily caught in traps, and at that place are sold at 6¼c. each. In east Florida they are seen in the villages and resort to the orange groves about them, where they frequently breed.” Writing to his wife, Lucy, when this painting was being finished, he reported that his assistant, Lehman, was working on the orange branch.

Audubon always responded emotionally to the voices of doves: “Listen—for at such a moment your soul will be touched by sounds—to the soft, the mellow, the melting accents, which one might suppose inspired by Nature’s self, and which she has taught the Ground Dove to employ in conveying the expression of his love to his mate, who is listening to them with delight.” And yet, in another paragraph he can state unsentimentally, “Their flesh is excellent.”

228. Key West Quail Dove [Key West Dove]

Geotrygon chrysia [Columba Montana]

Order: Columbiformes

Family: Columbidae

(Song)

When Audubon visited the Florida Keys in 1832, several West Indian doves were making regular visits to these tropical isles. On May 6th, with a Sergeant Sykes who was stationed at Key West, he secured a dove new to him, the bright rusty bird which he has portrayed here among lavender morning glories. These richly-colored doves hid in the dense thickets of West Indian hardwoods that grew about the shady ponds, and cooed mournfully as all doves do. To his ears their moaning notes sounded like whoe-whoe-oh-oh-oh. Later he saw more of them as they crossed the blue-green waters between Cuba and Key West, flying in small loose flocks of five or six to a dozen. By midsummer the doves became numerous enough to enable sportsmen to shoot as many as a score in a day.

Today Key West has been stripped almost bare of its native trees; the town has grown and the U.S. Navy has taken over. Birds that live on islands are always more vulnerable, more easily exterminated, than birds that reside on large continental areas. The Key West quail dove, ruddy quail dove, Zenaida dove, and perhaps one or two others which lived in the Keys in those days are gone. Only one West Indian dove, the white-crowned pigeon, still makes its annual pilgrimage across the Gulf from Cuba, nesting on the small mangrove keys between Key West and Cape Sable.

229. Blue-Headed Quail Dove [Blue-headed Pigeon]

Starnoenas cyanocephala [Columba Cyanocephala]

Order: Columbiformes

Family: Columbidae

(Song)

This attractive dove from Cuba is one of Audubon’s “unacceptables.” It has never been seen or taken in the United States since he reported seeing it in the Florida Keys, except for a specimen from Miami which is believed to have been a zoo escape. Inasmuch as the species has never been confirmed by a specimen, the A.O.U. Checklist Committee has transferred it to the hypothetical list.

Audubon wrote, “A few of these birds migrate from the island of Cuba to the Keys of Florida, but are rarely seen, on account of the deep tangled woods in which they live. Early in May 1832, while on a shooting excursion with the commander of the United States Revenue Cutter Marion, I saw a pair of them on the western side of Key West. They were near the water picking gravel, but on our approaching them they ran back into the thickets, which were only a few yards distance. Several fishermen and wreckers informed us that they were more abundant on the ‘Mule Keys’; but although a large party and myself searched these islands for a whole day, not one did we discover there. I saw a pair which I was told had been caught when young on the latter keys, but I could not obtain any other information respecting them, than that they were fed on cracked corn and rice, which answered the purpose well.”

The background, with its grasslike wild poinsettias, was painted by George Lehman.

230. Carolina Parakeet [Carolina Parrot]

Conuropsis carolinensis [Psitacus Carolinensis]

Order: Psittaciformes

Family: Psittacidae

This, the only parrot endemic to the United States, became extinct early in this century; but in Audubon’s day it was still so abundant that he was able to secure a basketful with a few shots in order to choose good specimens for his drawing, of which he proudly wrote, “Doubtless, the reader will say, while looking at the seven Parakeets in the plate, that I spared not my labor. I never do, so anxious am I to promote his pleasure.”

Farmers destroyed them in great numbers, he reported: “Whilst busily engaged in plucking off the fruits or tearing the grain from the stalks, the husbandman approaches them with perfect ease, and commits great slaughter among them. . . . The gun is kept at work; eight or ten, or even twenty, are killed at every discharge. The living birds, as if conscious of the death of their companions, sweep over their bodies, screaming as loud as ever, but still return to be shot at until few remain alive. I have seen hundreds destroyed in the course of a few hours.” Little wonder that Audubon was to write in his later years: “Our Parakeets are rapidly diminishing in number, and in some districts, where twenty-five years ago they were plentiful, scarcely any are now to be seen.”

Today it is still possible to see parrots in the United States, but not Carolina parakeets. Most of them are escapees from the pet trade—monk parakeets and canary-winged parakeets from South America, Australian budgerigars, and a dozen other species of exotic origin.

Coccyzus minor [Coccyzus Seniculus]

Order: Cuculiformes

Family: Cuculidae

When Audubon visited exotic Key West in 1832 he must have been truly inspired, for while there he painted some of his finest pieces—among them the dramatic dove series and this dynamic portrait of a mangrove cuckoo. The old house where he stayed still stands, surrounded by strange tropical trees, perhaps lineal descendants of the very trees whose leaves and blossoms he used in some of his backgrounds.

The mangrove cuckoo, or Maynard’s cuckoo as this race was formerly called, is rather like the familiar yellow-billed cuckoo that lives throughout the southern and eastern states, but its breast is washed with a creamy buff. About a foot long, much slenderer than a robin, it is a sinuous, long-tailed bird, as all cuckoos are, with slow deliberate movements. A native of Central America and the West Indies, it reaches its northern limits in the Keys and along the west coast of Florida north to Tampa Bay. In the subtropical terrain and turquoise waters of the Keys, where great white herons wade the shallows and man-o’-war birds hang motionless overhead, it is one of the most characteristic but least known inhabitants. It lives almost unobserved in the wilderness of red and black mangrove, seldom noticed as it slips through the gloomy labyrinth of roots which project like stilts from the saline water. A sharp eye might spot it perched motionless on a branch surrounded by masses of leathery leaves.

Coccyzus americanus [Coccyzus Carolinensis]

Order: Cuculiformes

Family: Cuculidae

(Songs; Call)

Old World cuckoos lay their eggs in the nests of other birds. New World cuckoos do not; they have not evolved the habit of brood parasitism. The yellow-billed cuckoo, like its congener, the black-billed, deposits two to four pale blue-green eggs. Cuckoos are slender, almost reptilian birds, more often heard than seen. The yellow-bill utters a rapid throaty ka ka ka ka ka ka ka ka ka ka ka ka kowp-kowp-kowp (retarded toward the end). The black-bill has a rhythmic cu cu cu, cucucu, cucucu, cucucu, etc., a melancholy song that can sometimes be heard at night. Country people, believing that their vocalizations signalled rain, once called them “rain crows.”

In this spirited composition, one of his finest, Audubon has shown a pair of yellow-billed cuckoos in a fruiting pawpaw. One has caught a tiger swallowtail butterfly. Actually, they seldom eat butterflies; tiger swallowtails would elude these phlegmatic caterpillar-eaters with ease. One of Audubon’s correspondents noted that cuckoos are much more numerous some years than others, a fact that has been confirmed fully since then. It is believed that cyclic outbreaks of tent caterpillars coincide with these fluctuations.

Coccyzus erythropthalmus

Order: Cuculiformes

Family: Cuculidae

(Song; Call; Call)

This elaborate composition was probably a cooperative effort painted by Audubon with the help of his talented young assistant, Joseph Mason. Although Audubon does not credit Mason with painting the flowers, Mason claimed that he did so. Audubon wrote to his wife: “He now draws flowers better than any man probably in America.”

The black-billed cuckoo is only a bird of passage in the Gulf states and Audubon saw it but a very few times during his stay in Louisiana. He wrote, “It being so scarce a species in Louisiana, I have honored it by placing a pair on a branch of Magnolia in bloom, although the birds represented were not shot on one of these trees, but in a swamp near some, where the birds were in pursuit of such flies as you see figured, probably to amuse themselves.”

Writing further about the species, he indicated that he found it not infrequently in Labrador and Newfoundland, which is highly unlikely. His memory, when writing at a later date, was often faulty, particularly when he was not able to refer to his earlier journals.

The black-billed cuckoo is duller in color than the yellow-billed cuckoo (plate 232) and has much smaller white tail-spots. The lower mandible is black, not yellow, and there is no rufous in the wings. The voice, a rhythmic, tri-syllabic cu-cu-cu, cu-cu-cu, cu-cu-cu, cu-cu-cu, is distinctive and can sometimes be heard on warm, still nights.

Tyto alba [Strix Flammea]

Order: Strigiformes

Family: Tytonidae

(Scream; Kleak-kleak call; Juvenile begging snore)

This long-legged, pale, monkey-faced bird is the owl of Gray’s Elegy in a Country Churchyard and other English literary works. It is the spook that haunts old barns, belfries, great hollow trees, and caves. It does not give away its presence by hooting as some owls do, but has a shrill rasping snore, or hollow hissing sound—shiiish—which reminded Audubon of “an opossum about to die of strangulation.”

In his Ornithological Biography, Audubon stated that the barn owl of America was a new species, distinct from the barn owl of Europe. He based this on a marked difference in the structure of the feathers that fringe the operculum or ear opening. On this evidence he changed the scientific name to Strix Americana. This judgment has been overruled, and today American and European birds are considered conspecific. Indeed, few species are more cosmopolitan. The barn owl is nearly worldwide in tropical and temperate regions; in the Americas it ranges from southern Canada to Tierra del Fuego, avoiding the higher altitudes.

The two birds shown in this plate were given to Audubon by Richard Harlan of Philadelphia. They had been brought from the south, and were fine adult birds in excellent plumage. The original painting, which is in the collection of the New-York Historical Society, was on a white sheet of paper. The gloomy night background was added later, presumably by Havell, the engraver, who often improvised his own background when he felt one was needed.

235. Eastern Screech-Owl [Mottled Owl] i

Otus asio [Strix Asio]

Order: Strigiformes

Family: Strigidae

(Descending trill; Monotonic trill; Screech calls and bill clap)

Audubon has shown one gray screech-owl and two reddish ones in this composition. He stated that the gray bird was an adult and the reddish ones were young. In this he was mistaken. Actually, these differences in color have nothing to do with age, sex, or season. They are color phases. Red birds and gray birds may often be paired, or they may be the products of the same brood.

This wide-ranging little owl, found from southeastern Canada to Mexico, is perhaps the most familiar owl in eastern North America. Where barred and great horned owls dominate the night world, screech-owls might be scarce; but in rural communities or towns that are devoid of these large nocturnal predators that eat little owls, the tree surgeon may be the screech-owl’s worst enemy.

In the eastern half of the continent, where screech-owls come in two color phases, they give voice to a mournful whinny at night, a tremulous wail running down the scale. This call is imitated easily and the birds will often respond. In western North America, where they are either gray or dull brown, never red, screech-owls do not have the descending whinny. Instead they sing a series of hollow whistles on one pitch, starting slowly then running into a tremolo, with the rhythm of a small rubber ball bouncing to a standstill. The western screech-owl is now regarded as a separate species.

Bubo virginianus [Strix Virginiana]

Order: Strigiformes

Family: Strigidae

(Pair duet; Female squawk; Fledgling begging call)

The deep, measured hooting of this nocturnal hunter sounds from the woodlands as dusk settles over the land. Alert to the slightest rustle of a small animal in the shadows, it glides on noiseless wings through the trees, ready to strike quickly.

Its wide yellow eyes and the ear tufts (which have nothing to do with its real ears) give the bird a cat-like look—in fact, in the foggy forests of Newfoundland, lumberjacks call it the “cat owl.” Distributed widely, it thrives from Labrador and Alaska to South America and varies from near-white at the edge of the Arctic to dusky in more humid regions. It is a resident of every state on the continent and even though it has the handicap of size (nearly two feet long, with a wingspread of four to five feet), it has the wits needed to survive even in settled farming country. Its nests have been seen even in the rocks on the Palisades close to the George Washington Bridge at the very threshold of New York City. In some places these birds hide their white eggs in hollow trees; in others, they appropriate old crow’s nests. So aggressive is this magnificent predator and so powerful are its spring-trip claws that even an eagle cannot stand up to it. In Florida, Charles Broley, the “eagle man,” found that one bald eagle’s nest in twenty had been commandeered by horned owls, forcing the original owners to rebuild their massive nests elsewhere.

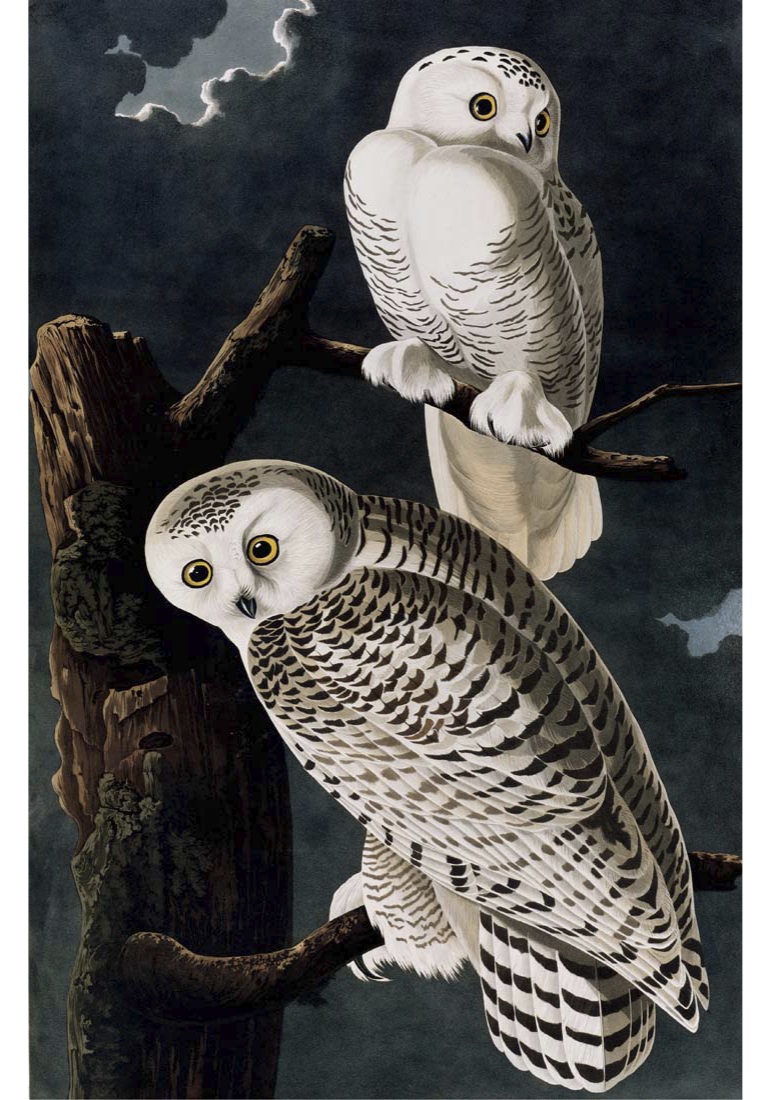

Nyctea scandiaca [Strix Nyctea]

Order: Strigiformes

Family: Strigidae

(Male hoot; Mewing whistle)

At home in the far North, the snowy owl sits upon its hillock, surveys its bleak domain, and intones its baleful booming to the polar sky. It has few enemies, chiefly the arctic fox and the Eskimos, who find the eggs of Ookpikjuak very palatable.

The key to life in the Arctic is the lemming, the little mouse-like mammal that increases so rapidly even its natural enemies cannot keep it in check. Periodically, when it reaches saturation, there is a population crash. In peak years, the snowy owl waxes fat on the lemming horde, but when the depression comes it must leave the barren tundra and seek food elsewhere. About every fourth year flights of these big ghostly owls drift into the United States; at longer intervals invasions of thousands pour across the border.

As one would expect of birds of the midnight sun, they are not as nocturnal as other owls, but fly abroad by day, searching the marshes, open plains, and dunes along the sea for rabbits and other four-footed fare. Persecuted by trophy hunters, few survive the winter to make the return trip. However, one year, several spent the winter successfully at a dump in the Bronx in New York City, where they caught rats and escaped notice because at a distance they looked like bundles of newspaper. The fuzzy young of all owls are white and are, therefore, sometimes taken for snowy owls.

Surnia ulula [Strix Funerea]

Order: Strigiformes

Family: Strigidae

(Male advertising song; Screeching call or screeee-yip followed by yelping call; Fledgling solicitation call)

This diurnal owl, which ranges the cold boreal forests across Canada and Alaska, was unknown to Audubon. He confessed, “It is always disagreeable to an author to come forward when he has little of importance to communicate to the reader, and on no occasion have I felt this more keenly than on the present, when introducing to your notice an Owl, of which the habits, although unknown to me, must be highly interesting, as it seems to assimilate in some degree to the diurnal birds of prey. I have never seen it alive, and therefore can only repeat what has been said by one who has.” He quoted Dr. Richardson, who knew it in the “fur countries,” from Hudson Bay to the Pacific: “[It] is more frequently killed than any other Owl by the hunters which may be partly attributed to its boldness and its habit of flying about by day. . . . In the summer it feeds principally on mice and insects, but in the snow-clad regions where it frequents in the winter, neither are to be procured and it then preys mostly on ptarmigan.”

This rather hawk-like owl, also found across northern Europe and Asia, is smaller than a crow and has a rather longish tail. It often perches at the tip of a conifer like a kestrel and does much of its hunting by day. During some winters a few reach the northern border states and it is then, with luck, that the birder might see one.

Strix varia [Strix Nebulosa]

Order: Strigiformes

Family: Strigidae

(Two-phrase hoot; Pair caterwauling)

Audubon knew this widely distributed owl of the swampy woodlands very well and nowhere did he find it more abundant than in his beloved Louisiana. He wrote: “How often, when snugly settled under the boughs of my temporary encampment, and preparing to roast a venison steak or the body of a squirrel, have I been saluted with the exulting bursts of this nightly disturber of the peace—Its whah, whah, whah, whah-a, is uttered loudly, and in so strange and ludicrous a manner, that I should not be surprised were you to compare these sounds to the affected bursts of laughter which you may have heard from some of the fashionable members of your own species.”

The original painting of the barred owl did not include the squirrel. The squirrel, painted separately, was added by Havell when he made the engraving for the Elephant Folio. Of course, no squirrel would laugh in the face of a barred owl as this one seems to be doing. It is questionable how often a squirrel would fall into the talons of a barred owl inasmuch as the owl is a nocturnal hunter while the squirrel spends the night hours in the security of a hollow tree. However, Audubon stated that the owl destroys a number of squirrels during the twilight.

One of the best places to see barred owls is at the Corkscrew Sanctuary of the National Audubon Society in Florida, where from the boardwalk visitors can often spot one or more perched in the moss-draped cypress trees.

240. Great Gray Owl [Great Cinereous Owl] i

Strix nebulosa [Strix Cinerea]

Order: Strigiformes

Family: Strigidae

(Male territorial hooting; Female contact call; Fledgling begging call)

This, the largest North American owl, is a denizen of the dense conifer forests from Hudson Bay to Alaska. There are also small outpost populations in the western mountains south to northern California and Colorado. Its eyes are remarkably small for its large, puffy head and are dwarfed by the large facial discs. A black chin-spot is bordered by white patches that look very much like large white moustaches.

Only rarely do stragglers drift in winter to the Great Lakes and New England, probably when there is a shortage of rodents on their home turf. During the winter of 1978–79, northern New York and New England experienced the largest invasion of these big owls in 90 years. Birders by the thousands added the great gray to their life-lists.

Although the great gray owl has always been an extremely rare bird in New England, Audubon reported that “it has been procured near Eastport in Maine, and at Marblehead in Massachusetts, where one of them was taken alive in February of 1831. I went to Salem for the purpose of seeing it, but it had died and I could not trace its remains.” Later, in the winter of 1832, he saw one himself, “flying over the harbour of Boston, Massachusetts, amid several gulls all of which continued teasing it until it disappeared.”

Asio otus [Strix Otus]

Order: Strigiformes

Family: Strigidae

(Male hoot; Female nest call; Alarm call)

Sitting tightly against the trunk of a conifer, this slender, crow-sized owl often goes undetected. Small parties may roost together in thick evergreen groves during the winter months, sallying forth as evening falls to catch mice and other crepuscular fare. This may include cardinals and white-throated sparrows, the last small birds to go to bed at dusk.

Superficially, the long-eared owl suggests an undersized great horned owl, but its “horns” are closer to the center of the forehead and the bird is striped lengthwise rather than barred crosswise beneath.

One gains the impression when reading Audubon that this owl must have been more numerous during his time. It is one of the most secretive owls, seldom making itself known by its low moaning hooooo or its catlike calls, which are quite unlike the bold hootings of barred owls or great horns. When performing its reproductive duties it usually appropriates last year’s nest of a crow or a hawk.

The continental range of the long-eared owl is wide, from coast to coast across the forested parts of Canada and southward to the central states. In winter many move as far south as the Gulf states and central Mexico. It is also found throughout many of the more wooded parts of Europe and Asia and locally in North Africa.

242. Boreal Owl [Tengmalm’s Owl] i

Aegolius funereus [Strix Tengmalmi]

Order: Strigiformes

Family: Strigidae

(Male song; Skiew call)

Audubon encountered this little northern owl only once, a male that he procured “at Bangor, Maine, on the Penobscot River, in the beginning of September, 1832.” However, he was unacquainted with its habits, never having seen another individual alive.

This small earless owl, so similar to the even smaller saw-whet owl, is distinguished by the black facial discs framing its whitish face and the dense white spotting on its crown. It is conspecific with the Tengmalm’s owl of northern Europe and was recognized as such by Audubon. Later it was thought to be a different species and was given the name “Richardson’s owl.” When the New World and Old World birds were again lumped as races of the same species it was renamed “boreal owl.”

Although overlapping the range of the saw-whet owl in Canada, it is more northern, breeding from Labrador across central Canada to Alaska, where it inhabits the conifer forests and muskegs right to the edge of the barren tundra. A few reach the northern edge of the United States in winter.

Audubon’s contemporary, Dr. Richardson, whose name this owl bore for many years, wrote: “When it accidentally wanders abroad in the day it is so much dazzled by the light of the sun as to become stupid and it may then easily be caught by the hand. . . . On the banks of the Saskatchewan it is so common that its voice is heard almost every night by the traveler, wherever he selects his bivouac.”

243. Northern Saw-whet Owl [Little Owl] i

Aegolius acadicus [Strix Acadica]

Order: Strigiformes

Family: Strigidae

(Song; Call; Call)

The presence of this very tame little owl is often betrayed by the complaints and fussings of chickadees and titmice, just as the presence of the larger owls, the barred and the great horned, is made known by the furor of crows and jays. Once this little earless owl, smaller than a screech-owl, is located in a conifer, it can be taken in the hand. The trick is to approach slowly and hold its attention by waving the fingers of one hand a yard in front of its staring eyes while slyly slipping the other hand behind to grab it.

It is secretive in habit and therefore perhaps more common than is realized, unless one knows its night song—a mellow whistled too, too, too, too, etc., repeated mechanically in endless succession, often 100 to 130 times per minute.

Audubon wrote of finding the saw-whet, or “Little Owl” as he called it, nesting in Louisiana, Kentucky, and Tennessee, as well as in coastal Maryland and New Jersey. If so, the bird once enjoyed a wider range than it has today. It is basically a resident of the cool forests of southern Canada and the northeastern U.S. with a few nesting southward along the Mississippi River to northern Missouri and in the higher Appalachians to North Carolina. There is however, a movement to the south in winter, when some reach the northern parts of the Gulf states. In the West the bird ranges south to the mountains of central Mexico.

Clockwise from top center:

244. Little Owl [Little Night Owl]

Athene noctua [Strix Noctua]

Northern Pygmy Owl [Columbian Owl]

Glaucidium gnoma [Strix Passerinoides]

(Song)

(Song; Fledgling begging call)

Short-eared Owl i

Asio flammeus [Strix Brachyotus]

(Bark)

Burrowing Owl [Large-headed Burrowing Owl] i

Athene cunicularia [Strix Cunicularia and Strix Californica]

(Male coo-hoo song; Alarm chatter)

Order: Strigiformes

Family: Strigidae

This potpourri of owls reveals Audubon’s uncertainty about some of the ones he did not know. The two burrowing owls (left) were treated as two different species in Audubon’s original colorplate. The lower one was called the “Large-headed Burrowing Owl,” Strix Californica. Both were labeled males. Later in his octavo Birds of America, they were lumped as a single species; one was labeled male, the other female! Audubon relied on the writings of Thomas Say who first met the burrowing owl in the Rockies. It is curious that he never encountered this species in Florida, where it is widespread. However, he must certainly have seen it later, on his Missouri River journey. He had, by then, published his work on the birds.

The little owl (top, center) is European. Audubon, who was told that it was “abundant in Newfoundland,” drew this bird from a specimen purportedly taken near Pictou, Nova Scotia. Surely an error.

The two little birds at the upper right are pygmy owls, denizens of the western forests. They were drawn from a specimen taken on the Columbia River by Dr. Townsend.

The short-eared owl (lower, right) is nearly worldwide and Audubon knew it well. It was more numerous in his time than it is today.

245. Chuck-will’s-widow [Chuck Will’s Widow] i

Antrostomus carolinensis

Order: Caprimulgiformes

Family: Caprimulgidae

(Song; Song, wing clap, cluck and growl)

Audubon apparently witnessed this little scene on one occasion in the early twilight. He believed the little brightly colored snake, which he called the “Harlequin Snake,” to be quite harmless; but, in fact, it was the deadly coral snake. It seems unlikely that chuck-will’s-widows would eat snakes, as they feed primarily on large insects, especially moths which they catch in flight, literally engulfing them in their cavernous mouths.

When discovered during the day, chuck-will’s-widow may remain quiet or spring from its hiding place and flit silently away like a large moth. Its voice is rather like the well-known chant of its close relative, the somewhat smaller whip-poor-will, but less vigorous than the efforts of that bird, a distinctly four-syllabled chuck-will-wi-dow. This nocturnal species has replaced the whip-poor-will in the more southern parts of the United States, from the Atlantic west to the edge of the arid plains. Recently, it has been extending its range northward and has actually been found nesting in the southern tip of Ontario on Lake Erie and also in Connecticut and Long Island. At the same time the whip-poor-will has suffered a decline.

Caprimulgus vociferus

Order: Caprimulgiformes

Family: Caprimulgidae

(Song)

On warm summer evenings the chant of the whip-poor-will rings through the leafy woodlands, a vigorous oft-repeated whip-poor-weel or prrrip purr-rill, with accents on the first and last syllables. Audubon said that “hundreds” could sometimes be heard calling simultaneously, surely an exaggeration, but there is no doubt that this well-camouflaged night bird is not as numerous today as it was within living memory. On our seventy-acre estate in Connecticut, an oak forest that has been spared by the axe, there once were whip-poor-wills, but following a massive aerial spraying in our township twelve or fifteen years ago, their insistent voices have not been heard. Nor do we see the big saturnid moths on which they fed—the lunas, polyphemus, and ios that formerly came to the windows at night.

Audubon’s composition of the three whip-poor-wills gives good ecological information, depicting the oak leaves where the birds find concealment during the day while sitting lengthwise on the branches, and also the moths on which they feed. He has presented a cecropia and an io with the same fidelity that he has shown the birds.

Whip-poor-wills have a wide range from southern Canada through the eastern and central states to the Gulf of Mexico. They are also found in the middle American mountains from southern Arizona to Honduras.

247. Common Nighthawk [Night Hawk] i

Chordeiles minor [Caprimulgus Virginianus]

Order: Caprimulgiformes

Family: Caprimulgidae

(Call and booming)

This slim-winged relative of the whip-poor-will is poorly named, for it is neither a hawk nor strictly a bird of the night. Audubon correctly pointed out that “it may be seen . . . on the wing, during the greater part of the day, even when the atmosphere is perfectly turned clear and while the sun is shining in all its glory.”

The favorite time for hunting insects is at twilight, but nighthawks can be heard uttering their nasal cries at any time of night over cities where the lights create a glow giving the illusion of dusk. In fact, in some of the more wooded parts of the United States, the only breeding nighthawks are in cities and towns where they lay their two heavily freckled eggs on the gravelly surface of flat roofs. Shopping centers, supermarkets, and factories are favorite sites. There at dusk one can watch the aerial maneuvers of the males which climb erratically, dive earthward, and then zoom up sharply with a whir of the wings.

Nighthawks breed widely, but locally, from coast to coast, and from timberline in Canada to Panama. They spend the winter in South America. There seems to have been some decline in recent years, although they are no longer shot. Audubon wrote, “The beauty and rapidity of its motions render it a tempting object to sportsmen generally and its flesh is by no means unpalatable. Thousands are shot on their return to the south during the autumn when they are fat and juicy.”

248. Chimney Swift [American Swift] i

Chaetura pelagica [Cypselus Pelagius]

Order: Apodiformes

Family: Apodidae

(Chatter calls)

Although swifts look superficially like swallows, they are structurally quite distinct; nevertheless, Audubon preferred to call them “Chimney Swallows.” In his day the chimney swift was already switching from hollow trees to chimneys. He wrote, “Since the progress of civilization in our country has furnished thousands of convenient places to breed in, safe from storms, snakes, or quadrupeds, it has abandoned, with a judgement worthy of remark, its former abodes in the hollows of trees, and taken possession of the chimneys which emit no smoke in the summer season.” However, many swifts continued to use the ancient hollow trees which were still to be found in the uncut forests. He wrote, “Sycamores of gigantic growth, and having a mere shell of bark and wood to support them, seem to suit them best, and wherever I have met with one of those patriarchs of the forest, rendered habitable by decay, there I have found the Swallows breeding in spring and summer and afterwards roosting until the time of their departure.” He was shown a huge tree that housed an immense number of swifts. In the early morning he watched for half an hour as they poured forth in a continuous black stream. Calculating the square footage of the tree’s interior, he estimated that 9,000 swifts roosted there.

The winter home of the chimney swift was unknown until the 1940s when bands from marked birds were returned from the Amazonian slope of Peru.

249. Black-throated Mango [Mangrove Humming Bird]

Anthracothorax nigricollis [Trochilus Mango]

Order: Apodiformes

Family: Trochilidae

No birder can expect to see this hummingbird anywhere in the U.S. except in his wildest dreams.

Audubon’s friend, the Reverend Bachman of Charleston, wrote, “It affords me great pleasure to introduce to the lovers of natural history this species of Humming Bird as an inhabitant of the United States. The specimen which is now in my possession was obtained by Dr. Strobel of Key West in Florida. He informed me that he had succeeded in capturing it from a bush where he found it seated, apparently wearied after its long flight across the Gulf of Mexico, probably from some of the West India islands or the coast of South America. Whether this species is numerous in any part of Florida I have had no means of ascertaining. The interior of this territory, as its name implies, is the land of flowers and consequently well suited to the peculiar habits of the genus and . . . it is possible that not only this but several other species of Humming Birds may yet be discovered.”

The black-throated mango has an extensive range in the American tropics from Panama to northern Argentina. Whether the specimen actually came from Florida has been questioned and the A.O.U. Checklist Committee has not seen fit to accept it for the North American list.

Audubon portrayed the three males from the single specimen that was given to Bachman by Strobel. The females were drawn from a specimen in the Charleston Museum. The flowers were painted by Maria Martin.

250. Ruby-throated Hummingbird [Ruby-throated Humming Bird] i

Archilochus colubris [Trochilus Colubris]

Order: Apodiformes

Family: Trochilidae

(Calls, wings [mixed])

There are about 320 species of hummingbirds, most of which live in the American tropics. The ruby-throated hummingbird is the only one of this very large family that normally reaches eastern North America. Weighing scarcely as much as a copper penny, it flies across the Gulf of Mexico, a nonstop flight of 500 miles, for there are no islands in mid-Gulf on which to rest.

Audubon was fascinated by these feathered jewels. Endeavoring to collect them undamaged for his painting he tried shooting them with jets of water, a procedure he found unsatisfactory. He then tried an insect net with more success. To give the illusion of iridescence when painting them, he applied gilt pigment to the backs of the birds.

Audubon’s prose was charmingly florid when he wrote about hummingbirds: “Who on observing this glittering fragment of the rainbow would not pause, admire, and instantly turn his mind with reverence toward the Almighty Creator, whose sublime conceptions we everywhere observe the manifestations in his admirable system of creation? . . . No sooner has the returned sun again introduced the vernal season, and caused millions of plants to expand their leaves and blossoms to the genial beams, than the little Hummingbird is seen advancing on fairy wings, carefully visiting every opening flower cup. . . . Its gorgeous throat in beauty and brilliance baffles all competition. Now it goes to a fiery hue, and again it is changed to the deepest velvety black.”

251. Anna’s Hummingbird [Columbian Humming Bird] i

Calypte anna [Trochilus Anna]

Order: Apodiformes

Family: Trochilidae

(Song; Chatter calls; Chip calls)

Who was Anna? Was she a little girl who lived long ago, perhaps the small daughter of the naturalist who first described this species? Or his wife? Actually, the facts have a much more intriguing flavor. Lesson, a Frenchman of Audubon’s era, who wrote a monograph on the hummingbirds, noticed a new jewel among the shipment of hummers that he had just received from Mexico. With a romantic flourish he honored a lady of his acquaintance, Anna, the Duchess of Rivoli, by bestowing upon it her name. So to this day, Californians who watch the little creature buzzing about the hibiscus in their gardens, and know it by name, pay lip service to the memory of an unknown lady in a distant land.

Whereas eastern North America has only one hummingbird, the ruby-throat, California boasts six. Anna’s hummingbird is the largest of the lot (about four inches long) and is the only one with a red forehead. When winter approaches, the other Californian hummers withdraw into Mexico, toward the land of their origin where they consort with the more tropical members of their family, but Anna’s hummingbird, relieved of competition, darts about the California gardens all winter long, visiting even the smallest gardens in the heart of town. Recently it has been extending its range northward along the Pacific states and eastward into Arizona. Audubon drew this plate from specimens furnished to him in London.

252. Rufous Hummingbird [Ruff-necked Humming-bird] i

Selasphorus rufus [Trochilus Rufus]

Order: Apodiformes

Family: Trochilidae

(Aggressive twittering, chatter and chip notes; Aerial displays)

In the American tropics hummingbirds buzz about the blossoms in bewildering variety. There are 320 species at least, or nearly 700 if the subspecies are counted. Yet of all these, only one, the ruby-throat, crosses the broad waters of the Gulf of Mexico to eastern North America. Some ruby-throats continue until they reach the Gulf of St. Lawrence. There is, however, one other member of the family that is an even greater traveler, the rufous hummingbird, portrayed here by Audubon. Swarming northward through the Pacific states in spring, some of its numbers continue the marathon to Alaska, where they have been recorded as far as the 61st degree of latitude. To equal this the ruby-throat would have to fly to Greenland. In contrast to these two adventurers, there are other species so sedentary that they are unknown away from the slopes of a single Andean volcano!

The rufous hummingbird returns to its winter home in Mexico by way of the mountain meadows of the Sierras and the Rockies. There, in summer, the slopes are alive with hummingbirds of three or four kinds. California is visited by six species of hummingbirds and southern Arizona by at least ten. The rufous hummingbird is the only one of this tribe north of the border that possesses a bright rusty back.

Audubon gave drawing lessons to Maria Martin, Bachman’s sister-in-law, and she drew the hummingbird’s nest and the spiderflower, Cleome. The specimens were furnished by Thomas Nuttall.