FLOCKERS AND SONGBIRDS

Meadowlarks, Blackbirds, Orioles, Tanagers, and Finches

382. Bobolink [Rice Bunting] i

Dolichonyx oryzivorus [Icterus Agripennis]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Pink call; Chunk call)

The handsome bobolink went by many names in Audubon’s time. Although he inscribed his original watercolor “Rice Birds,” he wrote that “here they pass under the name of ‘Meadow Birds,’ in Pennsylvania they are called ‘Reed Birds,’ in Carolina, ‘Rice Buntings,’ and in the State of New York, ‘Bobolinks.’” He wondered about the winter home of this bird, which migrated along the South Atlantic seaboard in such numbers and which he saw irregularly in Louisiana. He suspected that it must be in the West Indies. Although bobolinks do go through the West Indies, they continue on until they reach the pampas of Argentina, making one of the longest migrations of any land bird in the world. While in Argentina, the males lack the black and white pattern of spring and summer and are more soberly colored, like their sparrow-like mates.

Audubon noted that in spring, when the northbound flocks are still assembled, they often sing in chorus. “When each individual is possessed of the same musical powers as its neighbors, it becomes amusing to listen to thirty or forty of them beginning one after another as if ordered to follow in quick succession—producing such a medley as it is impossible to describe.” On the bobolink’s nesting grounds in the northern states and southern Canada its aerial song, given in hovering flight over the fields, is ecstatic and bubbling, starting with low reedy notes and rollicking upward.

383. Eastern Meadowlark [Meadow Lark] i

Sturnella magna [Sturnus Ludovicianus]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Calls)

The meadowlark is not a lark, but an icterid, related to the orioles, red-wings and other New World “blackbirds.” Audubon sometimes used the alternate name, “Meadow Starling”—but it is not a starling either. The starlings are an Old World family, of which the introduced European starling is the most familiar.

There is no mistaking this brown bird of the fields with the broad white patch on each side of its tail and the black V across its yellow breast. Its flight, several rapid wingbeats and a short glide, is also distinctive.

Audubon became aware that there were two species of meadowlarks, but not before he had finished his Elephant Folio. In the seventh volume of his octavo edition he figured the western meadowlark which he called “Missouri Meadow-Lark.” He described the species and gave it, rather whimsically, the scientific name neglecta. He wrote, “Although the existence of this species was known to the celebrated explorers of the west, Lewis and Clark, during their memorable journey across the Rocky Mountains and to the Pacific; no one has since taken the least notice of it. . . . They say, on the 21st of June, 1805, ‘There is also a species of Lark, much resembling the bird called the Old Field Lark, with a yellow breast and a black spot on the croup.’”

In recent years this bird, so similar in appearance to the other meadowlark, but with such a different song, has been extending eastward, broadly overlapping the eastern bird in the prairie states.

384. Red-winged Blackbird [Red-winged Starling] i

Agelaius phoeniceus [Icterus Phoeniceus]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Calls)

Perhaps no bird is more numerous in the United States today than the handsome red-winged blackbird, which nests not only in every state of the “lower 48” but probably in every county, wherever there is the least bit of marsh to accommodate it. Although it may have been favored during the last century by agricultural practices which enhanced its survival and its numbers, the red-wing seems to have been extremely abundant even in Audubon’s day. The “Red-winged Starling,” or “Red-shouldered Marsh Blackbird,” as he called it, was “so well known as being a bird of the most nefarious propensities, that in the United States one can hardly mention its name without hearing such an account of its pilfering as might induce the young student of nature to conceive that it had been created for the purpose of annoying the farmer.” He describes the killing and the havoc made amongst them: “I have heard that upwards of fifty have been killed at a shot. . . . I have myself shot hundreds in the course of an afternoon, killing from ten to fifteen at every discharge. . . .”

Whereas many were shot for sport or in defense of the crops, some found their way to the table. Commenting on their edibility, Audubon wrote, “As an article of food, they are little better than the starling of Europe, or the crow blackbird [grackle] of the United States, although many are eaten and are thought good by the country people, who make pies of them.”

385. Red-winged Blackbird [Prairie Starling] i

Agelaius phoeniceus [Icterus Gubernator]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Calls)

Although taxonomists have divided the red-winged blackbird into at least fourteen different subspecies, five of them in California alone, only this one is so very different as to be instantly recognized. Because it usually lacks the yellow or buffy edges on its scarlet epaulets, it is sometimes known as the “bi-colored blackbird.”

Understandably, it was first described as a new species, and Audubon, who received his specimens from Dr. Townsend, concurred. He called it the “Prairie Starling,” then changed the name to “Crimson-winged Troupial,” and later to “Red-and-Black Shouldered Marsh Blackbird.” Many years later it was relegated to subspecific status, conspecific with the ordinary red-winged blackbird. Although Audubon claimed that the two specimens he received from Dr. Townsend were procured on the Columbia River, the range of this race as outlined by the A.O.U. checklist is “Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys of California from Tehama county south to Kern County and extreme northern Los Angeles County.”

Icterus spurius

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song, chatter call; “Chuck” call)

The orchard oriole, or “Hang-nest” as Audubon called it, has an interesting sequence of plumages which he illustrated on this plate. He shows two adult males with their deep chestnut and black plumage, a female, dull olive and yellow with a white throat, and an immature male that looks like the female parent with the addition of a black throat. The bird peeking from behind the nest is a young male changing into adult plumage. In his text Audubon pointed out that earlier naturalists thought they were different species.

The orchard oriole is the dominant oriole of the southeastern United States, a few homesteading northward to southern Ontario and southern New England and as far west as the 100th meridian and beyond on the Great Plains. The nest, as Audubon depicted it in this honeylocust, is shallower than the deep purse-like nest of the northern or “Baltimore” oriole, its flamboyant orange and black relative.

Audubon’s written accounts emphasize the contrast in our attitudes toward songbirds today as compared to those of his time. Of the orchard oriole he writes: “Their flesh is very good late in the season and is much esteemed by the Creoles of Louisiana.” He adds that “in autumn a great number are shot or caught in trap cages. It is easily kept in cages, for it sings with all the liveliness which it shows in its wild state.”

Without realizing it Audubon was to help change these attitudes simply by making people more aware of the beauty of birds.

387. Northern Oriole [Baltimore Oriole] i

Icterus galbula [Icterus Baltimore]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song, calls)

When George Calvert, the first Lord Baltimore, visited the settlement of Virginia he found many birds along the Chesapeake. None, however, had beauty so breathtaking as the flame-colored birds, smaller than robins, which were later to bear his name. Much impressed, so the story goes, he took their colors, orange and black, for his coat of arms.

Although Audubon portrayed them appropriately enough in a tulip tree, northern (Baltimore) orioles are particularly partial to elms. However, in some towns the spread of the Dutch elm disease has forced them to use other trees. The nest, deep as a handbag, is hung from the tips of the longest, most sweeping branches, where no cat would venture. One can help the feathered architects by putting out yarn and string, cutting them into lengths not exceeding ten or twelve inches so that the birds will not get entangled in them. They eagerly eat orange halves impaled on twigs.

Although these orioles usually winter in the tropics, a few winter along the Atlantic seaboard of the U.S., especially in North Carolina. As if following some unalterable schedule, they make their annual pilgrimage over tropical jungles, across or around the Gulf of Mexico, through the plantations of the Gulf states and ever northward until in early May they reach the elm-shaded towns of the Great Lakes, New England, and southern Canada, arriving within a day or two of the same date year after year.

388. Rusty Blackbird [Rusty Grackle] i

Euphagus carolinus [Quiscalus Ferrugineus]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Song, calls; Calls)

This grackle-like blackbird is rusty only in its winter plumage when it is richly washed and barred with that color. The rest of the year it is uniformly blackish, with just a hint of greenish reflections about the head, but these are hard to see, not like the bright iridescence of the grackles. This is the breeding blackbird of the Canadian northwoods and the muskeg country, summering in the U.S. only in the more boreal parts of northern New England. During migration and winter it inhabits the eastern states west to the 100th meridian and south to the Gulf of Mexico. In the western part of the continent it is replaced by the very similar Brewer’s blackbird, which Audubon encountered at Fort Union on his Missouri-Yellowstone River journey after he completed the Elephant Folio. He then described and figured this new species toward the end of Volume 7 in his octavo edition, naming it after his friend, Thomas Brewer. He may have seen this species earlier without realizing it because it is not uncommon in the southeastern states in winter, and those birds he saw in the company of cattle “in the pastures or in the farmyards, searching for food among their droppings, and picking up a few grains of the refuse corn,” indicate Brewer’s blackbirds rather than rustys, which prefer river groves and wooded swamps. And certainly those birds that Townsend reported from the Columbia River must also have been Brewer’s, not rusty, blackbirds.

Quiscalus major [Quiscalus Major]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Calls)

This large, iridescent blackbird with the long keel-shaped tail was drawn by Audubon, probably when he was in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1832, and the live oak and Spanish moss were filled in by George Lehman, who painted so many backgrounds during that period. The male grackle is shown below; the smaller brown bird is the female.

The range of this large coastal grackle has probably changed since Audubon wrote, “This elegant bird is an inhabitant of the southern states, to the maritime portions of which it is more particularly attached. It seldom goes farther inland than forty or fifty miles and even then follows the swampy margins of large rivers, as the Mississippi, the Santee, the St. Johns, and the Savannah. It is found in lower Louisiana but never ascends as far as the City of Natchez, and it abounds in the southeastern low grounds of the Floridas, and those of Georgia, South Carolina, the sea islands of the Atlantic coast, as far north as Carolina, beyond which none are to be seen.” Today this grackle seems to be extending its range north. It has reached southern New Jersey and scouts have even been reported from Long Island.

During recent years, a similar large grackle unknown to Audubon, the great-tailed grackle, has moved up from Mexico and spread into the southwestern states. Not as maritime as the boat-tail, it has moved east as far as Louisiana and north to Kansas.

390. Common Grackle [Purple Grackle] i

Quiscalus quiscula [Quiscalus Versicolor]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Call, song [Bronzed]; Calls, song [Purple mixed])

Audubon, philosophizing about the ambivalence of man towards the grackle, writes, “See how torn the husk is from the ear. . . . This is the tithe our Blackbirds take from our planters and farmers. But it was so appointed and such is the will of the beneficent creator. The Grackle follows the husbandman as he turns one furrow after another, destroying a far worse enemy of the corn than itself, for every worm which it devours would else shortly cut the slender blade and thereby destroy the plant. Every reflecting farmer knows this well and refrains from disturbing the Grackle at this season . . . But man is too often forgetful of the benefit which he has received. No sooner does the corn become fit for his own use than he vows and executes vengeance on all intruders. . . . Hark to the sound of rattles and the hallooing of the farmer’s sons and servants as they spread over the field. Now and then the report of a gun comes on the air. They are chased and killed in great numbers all the country round. . . .”

To this day, grackles are regarded as a scourge by some farmers. Unlike most other passerine birds, they are not protected by law and campaigns of wholesale extermination are directed against them. In spite of this, they probably are more abundant than they were in former times, having benefited by the spread of agriculture. Some winter roosts of grackles and other blackbirds in the southern states run into the millions.

391. Brown-headed Cowbird [Cow Bunting] i

Molothrus ater [Icterus Pecoris]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

The cowbird, like the European cuckoo, is a “brood parasite,” laying its eggs in the nests of other birds, thereby shirking parenthood. Audubon, who called this icterid the “Cow Bunting” when he painted this portrait, later changed it to “Cowpen Bird.” He wrote, “This species derives its name from the circumstances of its frequenting cowpens. In this respect it greatly resembles the European starling. Like that bird it follows the cattle in the fields, often alights on their backs, and may be seen diligently searching for worms and larvae among their dung. In spring, the cattle in many parts of the United States are much infested with intestinal worms, which they pass in great quantities, and on these the cowbird frequently makes a delicious repast.”

One of the last plates in Audubon’s Elephant Folio, plate 434, shows a miscellany of six species, among which is a young cowbird. This he later incorporated with the two adults shown here in his miniaturized plate in the octavo edition. He wrote that the specimen from which he drew it was the same young bird that his friend Thomas Nuttall had described “under the name ‘Ambiguous Sparrow,’ Fringilla ambigua at page 485 of his Manual of the Ornithology of the United States and Canada. On inspecting it, however, I at once felt convinced that it was nothing else than a young Cow-Pen-Bird, scarcely fledged, it having been found in the early part of the summer of 1830. With the view therefor of preventing further mistakes I thought it well to figure it.”

From top to bottom:

392. Tricolored Blackbird [Nuttall’s Starling]

Agelaius tricolor [Icterus Tricolor]

(Song, calls [mixed])

Yellow-headed Blackbird [Yellow-headed Troupial] i

Xanthocephalus xanthocephalus [Icterus Xanthocephalus]

(Song; Call, song [mixed])

Northern Oriole [Bullock’s Oriole] i

Icterus galbula [Icterus Bullockii]

(Song, calls)

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

In some of Audubon’s later bird portraits, such as these, which were painted with the assistance of his son John from specimens sent from the West by Nuttall and Townsend, time was the limiting factor. To keep up with the production schedule, backgrounds were often left out. In this case the figures were rearranged by Havell, who also furnished the branches.

The tricolored blackbird at the top was another of the new western species described by Audubon, a bird very similar in appearance to the ordinary red-winged blackbird, but so different in biology. It is the most highly colonial North American songbird, nesting in dense colonies often numbering many thousands. Audubon called it “Nuttall’s Starling,” but later changed the name to “Red-and-white-winged Troupial.”

The yellow-headed blackbirds in the center were called “Yellow-headed Troupials” and “Saffron-headed Marsh Blackbirds” by Audubon, who often seemed equivocal about the names he gave to birds.

The lower figure is “Bullock’s oriole,” the western counterpart of the “Baltimore oriole.” Recently the two forms have been lumped as conspecific—two well-marked races of a single species that has been given a new name—northern oriole.

From top to bottom:

393. Western Tanager [Louisiana Tanager] i

Piranga ludoviciana [Tanagra Ludoviciana]

(Song, call [mixed])

Scarlet Tanager [Black-winged Red-bird] i

Piranga olivacea [Tanagra Rubra]

(Song; Calls)

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

Two species of tanagers were combined on this single plate in the Elephant Folio, but were rearranged on individual plates in the smaller octavo edition. Maria Martin drew the red bay on which the birds are shown.

The upper two figures are males of the western tanager, which Audubon called the “Louisiana Tanager.” He wrote, “Wilson was the first ornithologist who figured this handsome bird. From his time until the return of Mr. Townsend from the Columbia River, no specimen seems to have been procured. That gentleman forwarded several males in much finer condition than those brought by Lewis and Clark. Some of these I purchased.”

The scarlet tanager (male, center; female, below) was more prosaically called the “Black-winged Red-bird” by Audubon, who commented on its spring arrival on the Texas coast. He reported, “On several of the islands in the Gulf of Mexico, I found it exceedingly abundant, and restrained in a great measure from proceeding eastward by the weather, which was unseasonably cold. Many were procured in their full dress, and a few in the garb of the females.”

To this day, birders in late April find scarlet tanagers ganged up on these islands that fringe the upper coast of Texas when a spell of bad weather grounds them after their tiring journey across the Gulf of Mexico.

394. Summer Tanager [Summer Red Bird] i

Piranga rubra [Tanagra Aestiva]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

In the South there are two “redbirds”: the “winter redbird” (the cardinal), which remains all year, and the “summer redbird,” shown here. Inasmuch as they are the only two birds in the eastern states that are all red, they are easily recognized, for one has a crest, the other has none. From the moss-draped live oaks or longleaf pines the summer tanager sings its robin-like phrases, but far more characteristic is the note with which it always announces itself, a staccato chicky-tuck, a note unlike that of any other bird. The yellowish female also says chicky-tuck, but she does not sing. Occasionally, if a storm sweeps up the coast in April, at the time when summer tanagers are making their hazardous passage across the Gulf, a few are carried as far as New England, but except for such acts of God the summer tanager is an unreconstructed southerner, seldom venturing across the Mason and Dixon Line. The other eastern species, the scarlet tanager, crimson with black wings, is a Yankee by adoption, spending the summer in the northern tier of states and southern Canada. In Latin America 400 other species of tanagers, garbed in vivid shades of red, blue, and yellow, vie with the parrots and trogons in making the tropics gay. In this composition, with his fine sense of pattern, Joseph Mason, who painted the grapevine, is at his best.

395. Northern Cardinal [Cardinal Grosbeak] i

Cardinalis cardinalis [Fringilla Cardinalis]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Song; Call)

Cardinals have been the favorite subjects of bird artists since Audubon’s day. One contemporary bird painter says that one commission out of every ten he receives is for a portrait of a cardinal. Bright red birds always have an irresistible appeal, whether they are framed on the living room wall or flying free about the snow-covered food shelf outside the window. Extolling the cardinal’s virtues, Audubon wrote, “In richness of plumage, elegance of motion, and strength of song, this species surpasses all its kindred in the United States.”

One would think a bird so brightly colored would surely migrate to the tropics, along with the tanagers and orioles, but, on the contrary, a cardinal that spends the summer in a garden is likely to winter there too, probably not wandering more than a quarter of a mile away—even in New England or southern Ontario, where the snow lies deep and the temperature drops below zero. We still think of the cardinal as more typical of the South, where it vies with the mockingbird for first place in the affections of garden lovers. Perched among the waxy leaves of a magnolia, the male chants in clear slurred whistles—what cheer, cheer, cheer, cheer, cheer! Once a favorite cage bird, trapped commercially by tens of thousands, it has grown more numerous; and because of feeding trays and sunflower seeds, it has extended its range to southern Canada, far north of its limits in Audubon’s day.

Pheucticus ludovicianus [Fringilla Ludoviciana]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

The male rose-breasted grosbeak is one of the most stunningly attractive birds to visit North America. Its mate is more modest, like a large overgrown sparrow with a big bill. Spending the winter in the tropics, from Mexico and the West Indies to Peru, the rose-breast returns in May to its summer woodlands in the northeastern and central states and southern Canada.

Audubon was on the Texas coast in April, 1837, when grosbeaks were arriving after their passage across the Gulf. They must have been blocked by inclement weather, as they sometimes are, and he reported, “I found it so abundant wherever we landed that hundreds might have been procured.”

Whereas the song of the scarlet tanager might be likened to “a robin with a sore throat,” that of the rose-breasted grosbeak suggests a robin that has been taking music lessons. It has a mellifluous, fluid quality, and seems to be delivered with feeling. Two male grosbeaks in a song duel often perform a memorable woodland duet. One evening while Audubon was camping on the Mohawk River and almost asleep, “suddenly,” he wrote, “there burst on my soul the serenade of the Rose-breasted birds, so rich, so mellow, so loud in the stillness of the night, that sleep fled from my eyelids. Never did I enjoy music more; it thrilled through my heart, and surrounded me with an atmosphere of bliss. Long after the sound ceased did I enjoy them. In the morning I awoke vigorous as ever, and prepared to continue my journey.”

From top to bottom:

Coccothraustes vespertinus [Fringilla Vespertina]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Fringillidae

Black-headed Grosbeak [Spotted Grosbeak] i

Pheucticus melanocephalus [Fringilla Maculata]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

The evening grosbeak (male shown at top) is one of the great success stories of our North American avifauna. In Audubon’s day it was known only from the Northwest; he never saw one, and the farthest east it had been recorded was Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, from where it was first described by Cooper in 1823. By 1850, it had wandered in winter as far east as Toronto, and by 1890, to Massachusetts. Since then, because of the tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands of feeders, proffering their favorite food, sunflower seeds, evening grosbeaks have proliferated. Their winter wanderings now take them well down through the eastern and central states; in years of massive movements some even reach the Gulf of Mexico. Reflecting their enhanced winter survival because of sunflower seeds, they now have extended their breeding range eastward across Canada to the Maritime Provinces and northern New England.

The black-headed grosbeak or “Spotted Grosbeak,” as Audubon called it, replaces the rose-breasted grosbeak (plate 396) in the western states and southwestern Canada. Although dissimilar in color and pattern, the two species are much alike in habits and voice. Where their ranges meet on the Great Plains they may occasionally hybridize. Audubon knew this species only through correspondence with his friend Thomas Nuttall. The three grosbeaks shown here may have been painted by Audubon’s son John from specimens received from the West.

Guiraca caerulea [Fringilla Cerulea]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

The male blue grosbeak, like a large version of the indigo bunting, can be separated from that bird by its larger bill and broad tan wing-bars. The brown females of the two species can be separated by these same characteristics.

In summer, this grosbeak’s range is extensive in brushy places, roadsides, and streamside thickets across the southern half of the United States and southward through Mexico to Costa Rica. Of its habitat, Audubon wrote, “While the Cardinal Grosbeak enlivens the neighborhood of our southern cities and villages, and frequents the lawn of the planter’s habitation, the present species, shy and bashful, retires to the borders of the almost stagnant waters used as reservoirs for the purpose of irrigating the rice plantations. . . . There where the alligator, basking sluggishly on the miry pond, bellows forth its fearful cries, or in silence watches the timid deer . . . where the watchful Heron stands erect, silent, and ready to strike its slippery prey, or leisurely and gracefully slips along the muddy margins; where baneful miasmata fill the sultry air . . . there you will meet with the Coerulean Grosbeak, timidly skipping from bush to bush, or over and amid the luxuriant rice, watchful even of the movements of the slave employed in cultivation of the fertile soil.”

The blue grosbeak was prized as a cage bird and Audubon noted, “Individuals are now and then exposed for sale in the markets of the southern cities, where, on account of the difficulty in catching them, they sell for about eight dollars the pair.” That was a lot of money in those days.

399. Indigo Bunting [Indigo Bird] i

Passerina cyanea [Fringilla Cyanea]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

It is quite likely that since the settlement of this continent the indigo bunting has gone through increases and declines, possibly cyclic, but more likely due to land use. In Connecticut, for example, indigo buntings are most numerous in cut-over brushland that has not yet gone back to second growth woodland. As the New England forest reclaims the worn out and abandoned farms, these birds increase until the shrubs and trees reach a certain size, then they drop out. Power lines maintain broad swaths through the forests and therefore provide the edge conditions which indigo buntings require.

Indigo buntings were favorite cage birds in Audubon’s day and he wrote, “Should the birds be caught when in full plumage they gradually lose their brilliant tints, which at length become extremely dull. . . . A similar alteration is observed to take place in Painted Finches which have been kept in cages for a certain period, as well as Baltimore and Orchard Orioles, and in the Bullfinch, Chaffinch, and other European birds.”

He informs us that “this species is best known to the Creoles of Louisiana by the name of Petit Papebleu. This is in accordance with the general practice of the first settlers of the state, who named all the finches, buntings and orioles, Papes.”

Commenting on this painting, Audubon wrote, “I have represented an adult female, two young males of the first and second year, in autumn, and a male in the full beauty of its plumage. They are placed on a plant usually called the Wild Sarsaparilla.”

Passerina ciris [Fringilla Ciris]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Plik call)

Like a gaudy tropical flower that has taken wing, the painted bunting livens the gardens on the outskirts of Charleston, Savannah, and many other southern cities and towns. Some call it the nonpareil, for no other American bird can match its dazzling patchwork of color. It is a bird of the low country, absent from the hills—a bird of the thickets and hedgerows, singing its bright pleasing warble throughout the heat of the day as insistently as the indigo bunting does in the thickets farther north. The female, lacking the coat of many colors, is just a little green finch, hardly to be noticed by anyone.

The five birds which Audubon has drawn on the sprig of chickasaw plum are engaged in a territorial squabble. In fact, so scrappy are the little brightly colored males that the Creoles of Louisiana once lured them into trip cages by placing inside them stuffed birds, mounted in belligerent poses. Thousands were caught and sold as cage birds in the markets of New Orleans, and many eventually reached the bazaars of London and Paris. Until recently, caged painted buntings could still be seen in the Cuban section of Key West, but it is illegal to confine them. The great national society that bears Audubon’s name has done much to change the attitude of an earlier era towards wildlife. Today sentiment alone is sufficient to safeguard songbirds, even though the United States can boast the best protective laws of any country in the world.

401. Dickcissel [Black-throated Bunting] i

Spiza americana [Fringilla Americana]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Fringillidae

(Song; Call; Flight call)

Suggesting a miniature meadowlark in appearance, the dickcissel, or “Black-throated Bunting,” as Audubon called it, sings its staccato dick-ciss-ciss-ciss or chup-chup-klip-klip-klip from the alfalfa fields and prairies west of the Appalachians and east of the Rockies. In Audubon’s day, it also bred rather commonly in the seaboard states from Virginia to Massachusetts. It was especially numerous in Pennsylvania where, during a trip from Philadelphia to Salem, New Jersey, with his son John and his friend Edward Harris, Audubon found a great number. He noted that the “males were molting or had already acquired their new plumage; the young, although full grown, had not yet assumed their second clothing . . . and the females were generally ragged.” Today, except for two or three localities in Maryland and Virginia, they no longer nest in the seaboard states, nor have they done so during this century. What caused them to shift westward no one knows, and it can only be surmised that it had something to do with changes in agricultural practices.

During migration the short buzzing call of the dickcissel may occasionally be heard as it passes overhead in the night sky. Although it travels mainly via Texas to its winter home in the American tropics, a few of its number drift eastward toward the coast each fall, and occasional birds may even remain during the winter at feeders, associating with the house sparrows.

Carpodacus purpureus [Fringilla Purpurea]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Fringillidae

(Song; Call)

In this age of environmental awareness, the hundreds of thousands of good people who feed birds would never think of harming a feather of the decorative purple finch, which looks so much like a sparrow dipped in raspberry juice; but things were different in Audubon’s day. He admits, “I have eaten many of them and consider their flesh equal to that of any other small bird, except the Rice Bunting [Bobolink].”

Today, in the eastern states, the purple finch is often joined at the feeding tray by the house finch (Carpodacus mexicanus), a very similar and closely related species. Audubon did not know the house finch, a bird of the arid Southwest which became established in the vicinity of New York City in the early 1940s, when cagebird dealers, selling these birds illegally, were about to be investigated. The dealers released them and, instead of dying off as some of us predicted, the finches have been raising three broods a year ever since, and have spread explosively.

Whereas the slightly smaller and redder house finch is addicted to suburban conditions and even cities, where it competes successfully with the house sparrow, the purple finch prefers the wooded countryside, nesting in small evergreens in the northern states and Canada. It is erratic in its winter movements, sometimes remaining in the North during the winter, at other times wandering as far south as the Gulf states. Audubon was familiar with this nomadic bird in climates as disparate as Labrador and Texas.

Pinicola enucleator [Pyrrhula Enucleator]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Fringillidae

(Song; Call; Call)

The pine grosbeak, a resident of the boreal forests of Canada, is an erratic wanderer which may appear as far south as Ohio or New Jersey one winter, then may be virtually absent south of the Canadian border during the next several years. The reason for these nomadic, possibly cyclic, wanderings is almost certainly failures of the food crop—the cones of spruces, firs, and other conifers upon which it depends; but when hard pressed it will make do with the seeds and fruits of other trees such as the mountain ash.

Although the pine grosbeak formerly bred in New Hampshire, Maine, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia, it seems to do so no longer, or only very rarely: another instance of a species shifting northward during the last century, probably in response to the general warming trend of the climate. The pine grosbeak’s home is in the great evergreen forest that stretches from Newfoundland and Labrador across Canada to Alaska and across the top of Europe and Asia as well. It ranges as far north as treeline, where the stunted conifers give way to frozen tundra.

The flight call of the pine grosbeak is a clear whistled tee-tee-tew, suggesting the cry of a greater yellowlegs, but with a more finch-like inflection. When flying overheard it can be whistled down and is so completely innocent that it will even alight on a person’s head or hands.

404. Redpoll [Lesser Red-poll] i

Carduelis flammea [Fringilla Linaria]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Fringillidae

(Song, calls)

This little arctic finch, so much like a goldfinch in shape and actions, but not in plumage, spends its summer in the willow scrub and brush of the Arctic tundra. It is circumboreal, a familiar bird across arctic Eurasia and on both coasts of Greenland as well as in northern North America, where it ranges from Newfoundland through the Hudson Bay region to northwestern Canada and Alaska. The redpoll winters from the southern parts of this vast breeding range to New England and the Great Lakes states. Audubon noted that in severe winters it traveled as far south as Pennsylvania, which indeed it still does. Its irregular movements, which are more like nomadic wanderings than migrations, take it to the central parts of the United States and casually farther.

The bright red cap on the forehead and the black chinspot are the redpoll’s field marks. Males have a pink flush on the upper breast; females do not. Purple finches lack the chinspot and are more extensively washed with red. The northernmost birds, which are frostier looking, were once regarded as a distinct species, the “hoary” redpoll.

Audubon, who painted these birds in Labrador in 1833, wrote: “Few birds exhibit a more affectionate disposition than the little Redpoll, and it was pleasing to see several on a twig feeding each other and passing a seed from bill to bill, one individual sometimes receiving food from his two neighbors at the same time.”

405. Pine Siskin [Pine Finch] i

Carduelis pinus [Fringilla Pinus]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Fringillidae

(Song, calls [mixed])

The siskin, which Audubon called the “Pine Finch” or “Pine Linnet,” replaces the redpoll (previous plate) in the boreal forests of spruce and fir south of the tundra. In every action it suggests the redpoll, but it is darker and more heavily streaked, and it lacks the distinctive red cap and pink breast. The only really diagnostic features are the touches of yellow in the wings and at the base of the tail. Living as it does in the high conifers, descending to the alders and weedy areas to vary its diet, the siskin would escape notice were it not for its characteristic calls, a loud chlee-ip or a light tit-i-tit, which are invariably uttered as it flies overhead from one feeding ground to another. Its buzzy shreeeee is quite unlike the call of any other bird.

Normally, siskins nest only in the spruce and fir country of Canada and the comparable “Canadian Zone” forests of northern New England and the upper Great Lakes, but after winter invasions occasional pairs may linger to breed as far south as southern New England, Pennsylvania, and Kansas. In winter, if the cone crop is good, they may not leave their northern home, but during other years their seasonal wanderings may take them as far south as the Gulf of Mexico.

The two birds shown here on a branch of black larch were painted in New Brunswick in 1832, while Audubon was traveling with his wife and two sons.

406. American Goldfinch [Yellow Bird] i

Carduelis tristis [Carduelis Americana]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Fringillidae

(Song, calls [mixed])

Audubon appropriately portrayed the “yellow bird” on a bull thistle, one of its favorite food plants. Although he knew this little bird best in Louisiana, where he said it appeared briefly in mid-winter, he found it in greatest numbers in New York State, particularly along the banks of the Mohawk River and the “New York Canal.” It was probably in that region that he painted this portrait.

It has been suggested that the reason goldfinches delay until the waning days of summer to raise their young (they are among the last birds to nest) is because they wait for the thistles, both for the silky floss with which to line the nest and for the seeds to feed their growing young.

Goldfinches are found from coast to coast and from the Gulf of St. Lawrence to the mountains of Georgia and the southwestern states, proceeding further south in winter to the Gulf of Mexico. In the fall the males lose their bright canary yellow and become dull olive brown, much like their female consorts. Their flight is distinctive, undulating like a roller coaster, each dip punctuated by a twittering tee-de-de. In the springtime they often travel northward in large, cheerfully conversing flocks.

Although some people still call the goldfinch “yellow bird” as Audubon did, “wild canary” is a more suitable nickname, because its song is very light and canary-like. The yellow warbler is more appropriately called “yellow bird” because it is yellowish all over, including the wings and tail.

407. Red Crossbill [American Crossbill] i

Loxia curvirostra

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Fringillidae

(Song; Call)

In the text accompanying this plate, Audubon wrote, “I have presented you with a flock of these Crossbills, composed of individuals of different ages, engaged in their usual occupations, on a branch of their favorite tree, the hemlock pine.” In his octavo edition he changed the name from “American Crossbill” to “Common Crossbill”; he had decided, correctly, that it was the same species as the widespread red crossbill of Europe. He noted: “This species I have found more abundant in Maine and in the British provinces of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, than anywhere else. Although I have met with it as early as the month of August in the great pine forests of Pennsylvania, I have never seen its nest. Many persons in the State of Maine assured me that they had found it on pine trees in the middle of winter, and while the earth was deeply covered with snow.”

The curious irregularity in the movements and life cycle of the red crossbill has always puzzled ornithologists. Nesting as it usually does in later winter, less often in the early fall—or almost any month of the year—poses a conundrum. Its travels from its nesting grounds in the cold boreal forests to evergreen forests elsewhere, sometimes as far south as the Gulf states, are equally irregular, and very puzzling. Audubon’s watercolor painting of these birds was presumably done in the summer of 1832, when he was in Maine.

Loxia leucoptera

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Fringillidae

(Song; Calls)

With their cross-tipped pruning shears, crossbills snip the rough scales from spruce cones and deftly extract the flat brown seeds. Strangely erratic in their habits, they are content to stay all winter in the cold forests of Quebec or Alaska if the branches are heavily laden with cones, but in years when the crop is poor they pull out. Some summers, the woods along the Maine coast are alive with crossbills, calling noisily to each other and flying about in little bands like big goldfinches; the next year not a single one might be seen. At intervals—sometimes years apart—flocks wander as far south as the central states, far from their home forests.

Not only are crossbills given to these unpredictable wanderings or “invasions,” but they might take it into their heads to nest at any time of the year—even during the bitter days of January, when the drifts lie deep over the land and only the long view of things would concede the eventual return of spring. On the other hand, their hidden nests in the evergreens have been found during the hottest days of August.

There are two kinds of crossbills in America. The best known is the red crossbill (plate 407), a dingy brick-red bird, but the handsomest is the white-wing, rosy red or dull pink with broad white wing-bars. Audubon has shown two males and two females on an alder twig which he picked in Newfoundland.

409. Rufous-sided Towhee [Towee Bunting] i

Pipilo erythrophthalmus [Fringilla Erythrophthalma]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

One hundred and fifty years ago, in an era when travel was slow and arduous, John James Audubon explored the woods, shores, and swamps from the Florida Keys to Labrador and from the Atlantic westward to the Mississippi and Missouri. During his lifetime he painted about 500 species of birds, nearly two-thirds of all those ever recorded in North America. Since then the face of the continent has been altered. Some birds have grown rare, and several have gone completely, while others like the rufous-sided towhee, shown here, are probably more numerous today than they were then. The “Towee Bunting,” as Audubon called it, benefited by the settling of the land. It likes brushy places where trees have been cut and scrubby growth is reclaiming the naked earth. Birds with such tastes—a preference for living in the young growth and woodland edges—have much more elbow room than they had when America was an unbroken wilderness of ancient trees.

The towhee is smaller and slimmer than a robin; black-backed if it is a male, brown-backed if a female. Both have rusty-red sides and show great white spots in their tails when they fly away. There are towhees of one kind or another over most of the United States. The typical eastern bird, shown here, attracts attention to itself by rummaging noisily among the dead leaves, flicking its tail, and by its note, a loud chewink! Its song sounds to some ears like drink-your-teeeee.

410. Savannah Sparrow [Savannah Finch] i

Passerculus sandwichensis [Fringilla Savanna]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

This little streaked sparrow of the open country enjoys the widest range of any of its family, being found at one season or another virtually throughout North America, from the Arctic to the West Indies and Central America. Races or subspecies vary from pale forms, such as the “Ipswich sparrow” of the Atlantic coast, to dark forms such as the “Labrador” and “Beldings” savannah sparrows. Superficially, the savannah sparrow suggests a song sparrow, but the short notched tail and the whitish stripe through the crown serve to distinguish it. The stripe over the eye may be yellowish, especially during the nesting season. As we walk across the fields, on the beach, or along the edge of the winter marsh, these unobtrusive little birds zip up, fly a short distance, and then dive back into the grass.

Audubon, commenting on its environment, wrote that “during winter . . . it is often seen in open plains of great extent, scantily covered with tall grasses. . . . Regardless of man, it approaches the house, frequents the garden, and alights on low buildings with as little concern as if in the most retired places.”

Audubon’s ear for bird voices left much to be desired. He wrote that the “Savannah Finch” or “Savannah Bunting” had no song and that the sounds it made were like those of the “common cricket.” Actually, the latter comment may not be too far off the mark. In the standard field guides its song has been described as “a dreamy lisping tsit-tsit-tsit, tseeee-tsaaay.”

411. Grasshopper Sparrow [Yellow-winged Sparrow] i

Ammodramus savannarum [Fringilla Passerina]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

This modest little sparrow of the open meadows has a wide range across the United States and southernmost Canada, but it must have been more numerous in the Northeast before the extensive fields of earlier days reverted to second growth woodland. Audubon commented, “From Maryland to Maine it is found in considerable numbers, and is not uncommon in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, and Connecticut.” This is hardly true today, where grasshopper sparrows are now seldom seen this side of the Appalachians. Even in the broad fields and prairies of the Midwest, where it is more frequent, it is subject to fluctuation, disappearing from some localities and building up in others. Audubon, puzzled about its migratory movements, wrote that “this species, indeed, never congregates, as almost all others of its tribe do, before they depart from us, but the individuals seem to move off in a sulky mood, and in so concealed a way, that their winter quarters are yet unknown.”

Were it not for its distinctive song, this inconspicuous little sparrow would seldom be ticked off on the birder’s checklist. The most typical song starts with two faint introductory notes, followed by an insect-like buzz, pi-tup zeeeeeeeeeeee, so thin that it does not register on some ears.

412. Henslow’s Sparrow [Henslow’s Bunting] i

Ammodramus henslowii

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

This secretive sparrow, one of the “little brown jobs” which are the despair of the beginning birder, was another of Audubon’s discoveries. He wrote, “I obtained the bird represented in this plate opposite Cincinnati, in the State of Kentucky, in the year 1820, while in the company of Mr. Robert Best, the curator of the western museum. It was on the ground amongst the tall grasses. Perceiving it to be different from any which I had seen, I immediately shot it, and the same day made an accurate drawing of it.” He named it “after the Reverend Professor Henslow of Cambridge, a gentleman so well known to the scientific world.”

Were it not for its song this bird would go almost undetected. It gives voice to one of the poorest vocal efforts of any bird, a hiccupping tsi-lick. It can often be heard on quiet nights as though it were practicing so as to do better during the summer days.

Although Henslow’s sparrow breeds locally east to the Atlantic states, its main range is in the upper midwestern states and southern Ontario. For reasons unknown it has nearly disappeared from the fields of the northeastern states where it formerly was common, and its range is also contracting at its western edge. Could pesticide campaigns on the bird’s wintering grounds in the southern states have decimated it? We don’t know. Curiously, there is an isolated nesting colony near Galveston, Texas.

413. Sharp-tailed Sparrow [Sharp-tailed Finch] i

Ammodramus caudacutus [Fringilla Caudacuta]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song)

This abundant sparrow of the coastal marshes is readily recognized by the bright ochre-yellow of its face, completely surrounding the gray ear-patch. Audubon reported that it “breeds from Texas along the coast to Massachusetts. Never in the interior.” Understandably, his knowledge of the range of the species was quite incomplete. Although it winters along the southern coasts as far as Texas, it does not nest south of North Carolina. He stated, “Within a few years this species has extended its range towards the eastern portions of the union, as far as the vicinity of Boston, perhaps farther. I doubt, however, that they ever reach the State of Maine and the British provinces, chiefly because the shores of those countries are rocky and very few salt marshes are met with there.” Actually, a gray-backed race of this species does inhabit the coastal marshes that are to be found locally between Maine and the Gulf of St. Lawrence. There is also a well-marked inland race in the marshes of the northern prairies. Colonies even exist around James Bay.

The standard field guides describe the song as a gasping buzz, tup-tup-sheeeeeee. Audubon points out one characteristic not mentioned in any field guide. He writes that in the flight of this species there is something that is “so different from that of any other Finch, that one can easily know them at first sight, if he only observes that when flying from one spot to another, they carry the tail very low.”

414. Seaside Sparrow [Sea-side Finch] i

Ammodramus maritimus [Fringilla Maritima]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Tuck call; Tsip call)

Just a little gray bird in the salt marsh may describe the seaside sparrow, but we are a bit shocked when we read in Audubon’s account: “Having one day shot a number of these birds, merely for the sake of practice, I had them made into a pie, which however, could not be eaten on account of its fishy flavor.” This belies his protestations that he often killed so many birds because of his love of science and his desire for knowledge.

Today, a limited amount of scientific collecting is still carried out, but only if it is sanctioned by the federal government or by state fish and game departments. It cannot be engaged in without a permit, and excesses are not tolerated. The mist net (for banding) and the binocular have replaced the shotgun.

The seaside sparrow, living in the salt marsh, must be able to drink salt water and eliminate the saline solution through special glands, in much the same manner as seabirds and certain other birds of the coast. In one race or another this dull sparrow exists along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts from Massachusetts to Texas. There is some migration of the northern population to more southerly latitudes, but a few birds remain during mild winters as far north as Long Island.

Audubon wrote, “The Rose on which I have drawn these birds is found so near the sea on rather higher lands than the marshes, that I thought it as fit as any other plant for the purpose. . . . It is sweetly scented and blooms from May to August.”

415. Seaside Sparrow [MacGillivray’s Finch] i

Ammodramus maritimus [Fringilla MacGillivraii]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Tuck call; Tsip call)

The seaside sparrow, which lives in the salt marshes from southern New England to Texas, has been split into nine different subspecies, some of them so distinctive that for many years they were regarded as distinct species. The very local and endangered “Cape Sable” seaside sparrow of southernmost Florida is one. The extinct “dusky” seaside sparrow of eastern Florida was another. Audubon took note of one which he named “MacGillivray’s Shore-Finch.” He wrote, “The species on which I have bestowed the name of my friend MACGILLIVRAY, chooses for its residence the salt marshes of our southern Atlantic shores, in which also are found the Sharp-tailed and Sea-side Finches of Wilson and other authors. . . . MACGILLIVRAY’S Finch is as yet very rare within the United States and has not been observed farther eastward than Sullivan Island, about six miles from Charleston in South Carolina; but it is very abundant in Texas.”

Actually, the range of MacGillivray’s finch, which differs from the other seaside sparrows in minor details, is roughly from North Carolina to Georgia; and the birds that Audubon found in Texas and at the mouth of the Mississippi are races that were differentiated later by other authors. No matter; the seaside sparrow is obviously a very plastic species, which may have evolved into various recognizable races after hurricanes swept away broad stretches of salt marsh, thus isolating populations of these birds.

416. Vesper Sparrow [Bay-winged Bunting] i

Pooecetes gramineus [Fringilla Graminea]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

The vesper sparrow’s identification tag is its white outer tail feathers, which flash conspicuously when it flies. Otherwise it would look rather like a song sparrow or any other little brown bird.

Although Audubon portrayed the vesper sparrow, or “bay-winged bunting,” as it was called in those days, beside a prickly-pear cactus (Opuntia), it is a bird of the green meadows that stretch across the northern states and southern Canada. Shy, it runs mouselike along the side of the road or pauses behind a weed until its pursuer passes. Then, hopping to the tip of a mullein stalk or a fence post, it sings. Its melody sounds like the brisk lay of a song sparrow but has a minor quality, with two low, clear introductory notes. At dusk, when other birds grow silent, it continues to sing from the fence line until darkness stills its voice.

Our native sparrows are a large family, somber, streaked little birds, but attractive in a modest way. Most of them sing well—some seem almost inspired—and their food habits of small insects and weed seeds make them economically desirable. So do not for a moment put them in the same category with the house sparrow, an immigrant which neither sings nor has overly endearing habits. They do not even belong to the same family, for the house sparrow is related to the weaver finches of the Old World.

417. Bachman’s Sparrow [Bachman’s Finch]

Aimophila aestivalis [Fringilla Bachmani]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

Audubon wrote that in the month of April, 1832, his close friend and collaborator, the Reverend Bachman of Charleston, discovered “near Parker’s Ferry on the Edisto River, in the State [South Carolina], a Fringilla which I had not seen before, and which on investigation I found had never been described. On searching for the same bird in the neighborhood of Charleston, I discovered it breeding in small numbers on the pine barrens about six miles north of the city.” Bachman informed him that it was more often heard than seen. He added that “this is decidedly the finest songster of the Sparrow family.” No one who has heard this singer in the southern pine forests would quibble with this evaluation. To quote our own Field Guide to the Birds: “The song is variable; usually a clear liquid whistle, followed by a loose trill or warble on a different pitch; for example, seeeee, slip, slip, slip, slip, slip, which may slightly suggest the ethereal quality of the hermit thrush’s song.

Bachman’s Pinewood Finch, as Audubon called it in his octavo edition, is confined to the southeastern states from Maryland and Ohio south to the Gulf and west to eastern Texas. It is local and seems to be disappearing in the northern parts of its range.

The bird shown in the drawing was presented to Audubon by Reverend Bachman. The fever tree branch on which is it perched may have been drawn by Maria Martin, who later became Mrs. Bachman.

418. Dark-eyed Junco [Snow Bird] i

Junco hyemalis [Fringilla Nivalis]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Song, call [mixed])

(Song; Song; Call)

This familiar winter bird, which until recently went by the name “slate-colored junco,” was known to Audubon and most country people at that time as the “snow bird”—an appropriate name because it was associated with cold weather, coming to the dooryard to accept crumbs. Today, the junco is among the most frequent patrons of the feeding station, preferring the smaller grains such as millet and cracked corn. A gray sparrow-shaped bird, it is readily identified by its conspicuous white outer tail feathers, which flash like signal flags as the bird flies away.

Audubon wrote that the junco was so gentle and tame, at the approach of hard weather, that it became a “companion to every child.” He was less sentimental when he wrote: “Their flesh is extremely delicate and juicy and on this account small strings of them are frequently seen in the New Orleans market.” He knew juncos as abundant winter visitors in Louisiana, where their twittering or tickering notes were a familiar sound in the brushy places and woodland edges.

As spring advances, juncos migrate to the colder woodlands of the northern border states and Canada. There, in the spruce forest, they sing their simple song, a loose, quavering trill on one pitch, suggesting a slower, more musical version of the chipping sparrow’s song.

419. American Tree Sparrow [Tree Sparrow] i

Spizella arborea [Fringilla Canadensis]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Calls)

The “winter chippy,” as it has been nicknamed, is readily known from the other rusty-capped sparrows by the single black spot or “stickpin” on its chest. Its summer home is the arctic scrub and dwarf willow thickets of Canada’s tundra. There it sings its bright song, but it is better known in winter when it visits the brushy fields and marsh edges of southeastern Canada and the northern states.

Hardier even than the white-throat, it may be the only sparrow to visit feeding stations in some of the colder sections. Its feeding note, a musical teel-wit, is quite unlike that of any other bird and seems to bespeak contentment with its lot.

Audubon associated this bird especially with New England. He wrote, “In the beginning of October, if the weather be cold, the tree sparrow is seen among the magnificent elm trees that ornament the beautiful city of Boston and its neighboring villages; and like the hardy, industrious people among whom it seems to spend the severe season by choice, it makes strenuous efforts to supply itself with the means of subsistence.” According to his correspondent, Dr. T. M. Brewer, it was the most common sparrow found near Boston during the winter, and so it is today.

This painting was one of the first birds painted by Audubon’s younger son, John, under the master’s guidance.

Spizella passerina [Fringilla Socialis]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Fringillidae

(Song; Calls)

“Few birds are more common throughout the United States than this gentle and harmless little finch,” wrote Audubon. His New England correspondent, Dr. Brewer, stated that “with hardly a single exception, it is the most numerous species in Massachusetts.” Whereas in Indian times the chipping sparrow was probably a bird of the open forest (and still is in some parts of the continent), it quickly adapted itself to town, village, and farm, where its chipping rattle soon became as familiar as the caroling of the robin. When the aggressive house sparrow arrived from Europe the inoffensive chippy undoubtedly felt the impact, and today it may not be nearly as numerous as when Audubon knew it.

The summer range of the chippy is very broad, extending from the boreal forests of Canada to the Gulf states and in the mountains to Nicaragua. It winters across the southern tier of states and northward along the coast, rarely to Long Island. At that season it is duller in color, having lost its bright rufous cap.

Audubon wrote, “It is one of the most confiding of our visitors, not infrequently forming its nest among the vines planted as ornaments to our piazzas.” In this attractive composition, which was presumably put together in Louisiana, Audubon’s protégé, Joseph Mason, painted the spray of black locust.

Spizella pusilla [Fringilla Pusilla]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Dawn song; Call)

The field sparrow, which inhabits the bushy pastures, open scrub, and field edges east of the Rockies, is one of several kinds of rusty-capped sparrows. It can be quickly identified from the two it most closely resembles, the chipping and tree sparrows, by its bright pink bill. A narrow white eye-ring gives it an innocent, large-eyed expression.

Modern field guides succinctly describe the song of the field sparrow as opening on deliberate, sweet, slurring notes, speeding into a trill. Audubon, whose ear was not as acute as his eye, wrote that its song was “remarkable, although not fine. It trills its notes like a young canary bird, and now and then emits emphatical though not very distinct sounds of some length. One accustomed to distinguishing the notes of different birds can easily recognize the song of this species.”

Actually, the term “Field Bunting,” the name Audubon used in the revised text in his octavo Birds of America, would have been more correct, if nomenclatural priority had been honored. All of our native “sparrows” are related to the buntings of the Old World and are not true sparrows such as the house sparrow, Eurasian tree sparrow, Spanish sparrow, etc. The latter are European, blood brothers of the weaver finches of Africa.

In discussing this drawing, Audubon wrote, “Travelling from Egg Harbour [New Jersey] towards Philadelphia, I found a nest of this species placed at the foot of a bush growing in almost pure sand. Near it were the plants which you see accompanying the figure.”

Zonotrichia leucophrys [Fringilla Leucophrys]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Song; Call)

A glimpse of this bird is enough to show that it is no ordinary sparrow. Distinguished in mien, with broad black and white stripes on its crown, it lacks the drabness of the common lot. To those of us who live along the Atlantic seaboard, the white-throated sparrow is much more familiar, a bird with similar head-stripes, but which has in addition a square white throat patch. We see white-crowns in migration, but not many; a few hop elegantly on the lawns in early May and sing their wheezy lyrical notes from the hedges. These transients are enroute to Newfoundland, Labrador, and the Hudson Bay country, the very threshold of the Arctic, where the last stunted spruces give way to the tundra.

West of the Appalachians the white-crown is much more numerous during the season of its passage, and in the far West it is positively abundant. There it can be heard, even in summer, singing from the edges of every bog in the high mountains. One race breeds on the coast as far south as California. Every garden in the Pacific states is visited in winter by some race of this handsome sparrow.

The plant which Audubon pictured in this attractive design is the summer grape (Vitis aestivalis) and the sparrow so furtively peeking from behind the big leaf is an immature individual, one of those tan-looking youngsters with pink bills that show up with the adults in the fall.

Zonotrichia albicollis [Fringilla Pensylvanica]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

These attractive little sparrows that come down from the cool forests of Canada to spend the winter in our gardens, where they patronize our feeding trays, were not so kindly treated in Audubon’s day. He records, “It is a plump bird, fattening almost to excess whilst in Louisiana, and afford delicious eating, for which purpose many are killed with blow-guns. These instruments are prepared by the Indians, who cut the straightest cane, perforating them by forcing a hickory rod through the internal partitions which intersect this species of bamboo. . . . Splints of wood or of cane are then worked into tiny arrows. . . . A smart puff of breath, is sufficient to propel an arrow with force enough to kill a small bird at a distance of eight or ten paces.”

Although Audubon knew the bird well on its wintering grounds, particularly in Louisiana where they were very abundant, it was not until he made his Labrador trip that he found them during the nesting season; but he never found a nest. In winter, when the white-throat invades the eastern United States, its song, four or five quavering whistles, can sometimes be heard on warm sunny days; but to hear it strong and clear one must visit its summer home in the northern spruce belt.

The dogwood branch on which the birds are portrayed was painted by Audubon’s assistant, Joseph Mason. It was perhaps the last drawing made by him during the term of his employ, which lasted for nearly two years.

424. Fox Sparrow [Fox-coloured Sparrow]

Passerella iliaca [Fringilla Iliaca]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

This, our largest sparrow, flashes a bright rufous tail as it flies before us across the wooded path, reminding us not a little of the hermit thrush, which also sports a reddish tail. The stunted firs and brush of boreal Canada and Alaska are the habitat of this robust finch during the summer season. In the higher mountains of the western states there are also populations of this species, ranging in color from dusky brown to dull gray.

The bright, musical song of the fox sparrow, a varied arrangement of short clear notes and sliding whistles, inspired Audubon to write, “Would that I could describe the sweet song of this Finch; that I could convey to your mind the effect it produced on my feelings when wandering on the desolate shores of Labrador! . . . The brilliancy and clearness of each note, as it flowed through the air, was so enchanting, the expression and emphasis of the song so powerful, that I never tired of listening.”

Like so many other songbirds, fox sparrows were fair game for the pot or for the cage in earlier days. Audubon reported, “Many of these birds are frequently offered for sale in the markets of Charleston, they being easily caught in figure-of-four traps. Their price is usually ten or twelve cents each. I saw many in the aviaries of my friends Dr. Samuel Wilson and the Reverend John Bachman, of that city.”

425. Lincoln’s Sparrow [Lincoln Finch] i

Melospiza lincolnii [Fringilla Lincolnii]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

Lincoln’s sparrow, a skulker “afraid of its shadow,” has a wide range across North America, breeding in the brushy bogs of boreal Canada and in similar situations in the higher mountains of the western states. It is scarcely noted by most birders during its migrations to and from its winter home in the southern states and Mexico.

Audubon did not meet this undistinguished sparrow until he visited Labrador for about three weeks in 1832. There he “chanced to enter one of those singular small valleys here and there to be seen. The sweet notes of this bird came trilling on the senses, surpassing in vigour those of any American Finch with which I am acquainted, and formed a song which seemed a compound of those of the Canary and Wood-lark of Europe. I immediately shouted to my companions who were not very far distant. Chance placed my young companion, Thomas Lincoln, in a situation where he saw it alight within shot, and with his unerring aim, he cut short its career. . . . Presuming it to be new, I named it Tom’s Finch, in honor of our friend Lincoln, who was a great favorite among us.”

Later, in his Ornithological Biography, Audubon changed the name to “Lincoln Finch,” and again, in his octavo edition, to “Lincoln’s Pinewood Finch.” Today the American Birding Association and the American Ornithologists’ Union are the arbiters of bird names, which are still changed occasionally—much to the irritation of some of the birding fraternity.

Melospiza georgiana [Fringilla Palustris]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

Audubon has placed this dweller of the cattail marshes and brushy swamps on a mandrake, or may-apple, a woodland plant. Birds, of course, may be found out of habitat at times, especially during migration.

This dark, rusty-capped sparrow, stockier than the chippy or the field sparrow, has a wide range east of the Rockies, breeding across Canada and south to the upper Midwest and the northeastern states. It winters from southern New England and the southern Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico.

The swamp sparrow’s song is similar to the chipping sparrow’s, but slower, sweeter, and stronger—sometimes on two pitches simultaneously. Again we question Audubon’s hearing when he tells us that this species is “destitute of song, merely uttering a single cheee which is now and then heard during the day but more frequently toward evening.”

At the bottom of the original painting Audubon wrote, “Drawn from Nature by Lucy Audubon. Mr. Havell will please have Lucy Audubon’s name on the plate instead of mine.” Commenting on this, Marshall Davidson, who researched the American Heritage edition of Audubon’s original watercolors, wrote, “It is likely, however, that Audubon had his wife’s name on the plate more to please her than to assign appropriate credit for the work. The bird appears to be his own drawing dating from about 1812. The plant, possibly done about 1825, is almost entirely Audubon’s work; his wife may have done the lower leaf, and she may have assisted on the upper leaf.”

Melospiza melodia [Fringilla Melodia]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call; Call; Call)

Audubon was partial to the demure song sparrow. He wrote: “Although its attire is exceedingly plain, it is pleasing to hear it, singing earlier in the spring and later in the autumn than almost any other bird.” Although he inscribed it as “song sparrow” on his original painting, he referred to it as the “song finch” in his octavo Birds of America.

To winter-weary people in the North, the voice of the song sparrow, like that of the spring peeper, is one of the true indicators of spring. The first migrants arrive with the spring thaws and may tune up when snow still lies deep on the ground. An inhabitant of thickets, brushy marshes, and roadsides, it often comes into suburban gardens. The nest, a grassy cup with three to seven spotted eggs, may sometimes be hidden in a low bush but is more often found on the ground among the grass and weeds. Audubon, noting this variation in nesting sites, imagined that “the old birds, finding by experience the insecurity of their ordinary practice of nesting on the ground, where the eggs are often devoured by crows, take themselves to the bushes to conceal their nests from their enemies.”

Throughout their broad range in North America song sparrows vary greatly in size. Those living in the more arid parts of the Southwest are small and pale; those in wetter regions are larger and darker. Audubon never knew these variants of the far West.

Calcarius lapponicus [Fringilla Laponica]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Calls; Call)

Like the snow bunting and the horned lark with which it often associates, the lapland longspur is circumpolar, spending the summer on the tundras that ring the polar seas. In winter, having lost its handsome nuptial plumage, it comes down to the fields and prairies of southernmost Canada and the United States.

Audubon first met this species in February, 1819. He wrote: “Walking with my wife, on the afternoon of that day, in the neighborhood of Henderson, in Kentucky, I saw immense flocks scattered over the open grounds on the grassy banks of the Ohio. Having my gun with me, I procured more than sixty in a few minutes. All the youths of the village turned out on this occasion, and a relative of mine, in the course of the next day, killed about six hundred. Although in rather poor condition we found them excellent eating.”

Human predation of this sort, now a thing of the past, probably never took as much of a toll on the birds as inclement weather. A single ice storm in March, 1904, accounted for the deaths of millions of migrating longspurs in southwestern Minnesota and northwestern Iowa. The bodies of 750,000 longspurs were strewn on the ice of two lakes alone, and this was only a small sample of the total catastrophe.

The bird at the left was engraved from a pastel, probably drawn in 1819 from one of the birds Audubon shot on the day described above. The other two birds were painted in watercolor many years later.

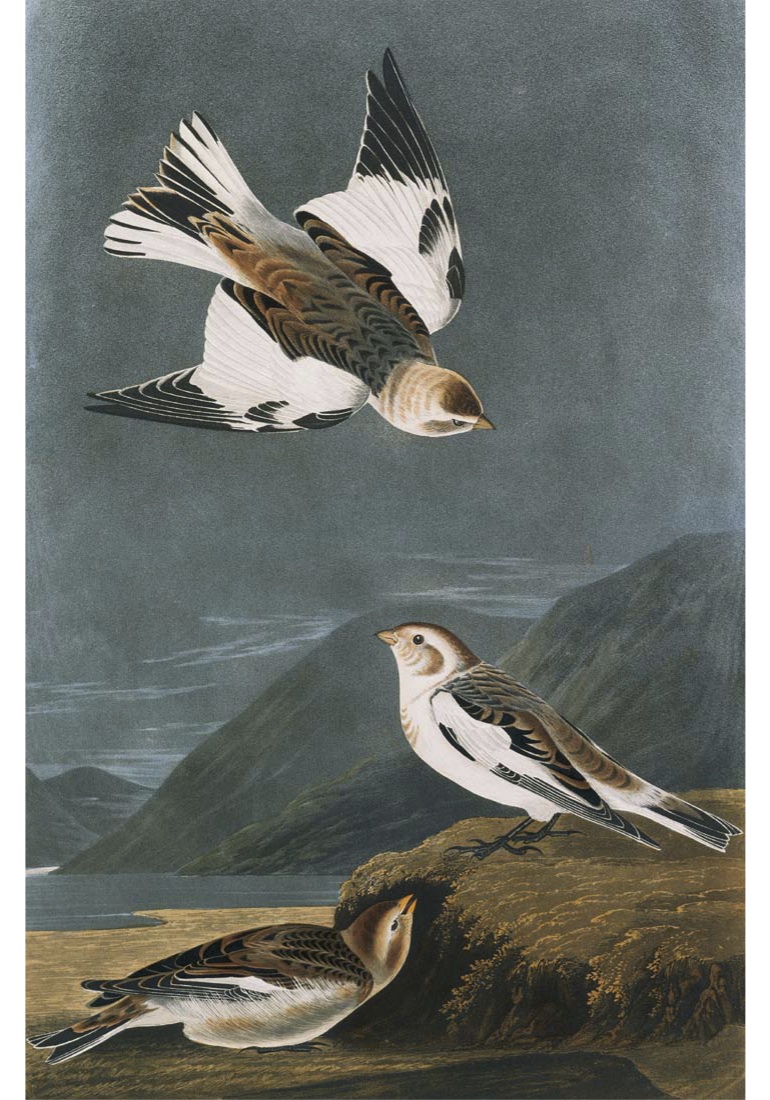

Plectrophenax nivalis [Emberiza Nivalis]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call; Call)

Painting a lyrical word picture, Audubon wrote, “As soon as the cold blasts of winter have stiffened the earth’s surface, and brought with them the first snow clouds, billions of these birds, driven before the pitiless storm, make their way towards milder climes. Their wings seem scarcely able to support their exhausted, almost congealed bodies, which seem little larger than the great feathery flakes of the substance from which these delicate creatures have borrowed their name. In compressed squadrons they are seen anxiously engaged in attempting to overcome the difficulties which beset them amid their perilous adventures. At last, when nearly exhausted by fatigue and hunger, some leader espies the wished for land, not yet buried in the snow. Joyful notes are heard from the famished voyagers, while with relaxed flight they float toward the spot where they are to find relief.”

No other songbird shows as much white nor lives so far north—to the very limits of land around the polar sea. Near the Eskimo settlements they are as familiar as the sparrows are in the cities to the south. At the approach of winter they leave the tundra for the frozen fields and shores of southern Canada and the northern states.

Commenting on the edibility of this winter visitor, Audubon wrote: “Because their flesh is savory and their appearance attractive, they are shot in great numbers.” He probably painted this plate in Boston during the winter of 1832–33.

Clockwise from top center:

430. Lark Sparrow [Lark Finch] i

Chondestes grammacus [Fringilla Grammaca]

(Song; Alarm call?)

Lark Bunting [Prairie Finch] i

Calamospiza melanocorys [Fringilla Bicolor]

(Song)

Song Sparrow [Brown Song Sparrow] i

Melospiza melodia [Fringilla Cinerea]

(Song; Call; Call; Call)

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Fringillidae

Although the lark sparrow breeds east to the Ohio and Mississippi valleys, Audubon never met it, but received specimens from his western correspondents. He called it the “Lark Finch,” later changing it to “Lark Bunting.” Today the next species goes by that name. This figure was not on Audubon’s original watercolor, which depicted the following two species, but was borrowed from another watercolor showing several species. The lark sparrow frequents brushy field edges on the western two thirds of the continent.

The lark bunting, center (male) and lower right (female), which Audubon called the “Prairie Finch” and later the “Prairie Lark Finch,” was known to him only through the specimens furnished by his friend Mr. Nuttall, who took them on the plains of the Platte River. The lark bunting is a bird of the prairies, basically east of the Rockies, from southern Canada to Texas. It is the state bird of Colorado.

The dark-looking song sparrow shown at the lower left is one of the twenty-five or more races of this species that have been described and named by taxonomists. This subspecies of the Northwest, often known as the “rusty song sparrow,” was regarded as a distinct species in Audubon’s day.

Clockwise from top center:

431. Chestnut-collared Longspur [Chestnut-coloured Finch] i

Calcarius ornatus [Plectrophanes Ornata]

(Song, call; Call)

Golden-crowned Sparrow [Black Crown Bunting] i

Zonotrichia atricapilla [Emberiza Atricapilla]

(Song; Call)

Rufous-sided Towhee [Arctic Ground-finch] i

Pipilo erythrophthalmus [Pipilo Arctica]

(Song; Call)

Black-headed Siskin

Carduelis notatus [Fringilla Magellanica]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Fringillidae

The chestnut-collared longspur, upper right, is a bird of the Great Plains. The specimen shown here was furnished by Dr. Townsend.

The black-headed siskin, upper left, is resident in the mountains of central America; therefore it is surprising to read Audubon’s statement: “While residing at Henderson, on the Ohio, I, one cold morning in December, observed five males of this species on the heads of some sunflowers in my garden, and after watching them for a little time, shot two of them.” What could they have been? The A.O.U. Checklist Committee has rejected this record.

The golden-crowned sparrow, center, a bird of the Northwest, is another species which was made known to Audubon through Nuttall and Townsend.

The two lower birds were designated by Audubon as the “Arctic Ground-finch.” This western form of the towhee was for many years regarded as a distinct species, known popularly as the “spotted towhee,” but it has since been lumped with the towhee of the East under the name of rufous-sided towhee. It differs in its extensive white spotting.

Clockwise from top center:

432. Lazuli Bunting [Lazuli Finch] i

Passerina amoena [Fringilla Amoena]

(Song; Call)

Clay-colored Sparrow [Clay-coloured Finch]

Spizella pallida [Emberiza Pallida]