DIVERS OF LAKES AND BAYS, WANDERERS OF SEAS AND COASTS

Loons, Grebes, Albatrosses, Fulmars, Shearwaters, Storm Petrels, Tropicbirds, Pelicans, Boobies, Gannets, Cormorants, Darters, Frigatebirds, Herons, Bitterns, Storks, Ibises, Spoonbills, and Flamingos

1. Common Loon [Great Northern Diver] i

Gavia immer [Colymbus Glacialis]

Order: Gaviiformes

Family: Gaviidae

(Male yodel; Pair tremelo; Pair wail)

Great northern diver, the name Audubon used, is still the name by which this bird is known in Britain, where it is a winter resident in small numbers—transients from Iceland, where it breeds. Loon, its American name, was undoubtedly derived from its maniacal laughter, a haunting sound on cool northern lakes during the summer months. There are tens of thousands of such lakes scattered across Canada and the northern tier of states. Loons leave their freshwater habitat when the leaves fall and migrate to salt water along both coasts. Lately their numbers have been somewhat threatened by two factors: in summer, the burgeoning numbers of vacationers who are taking over some of their favorite lakes; and, in winter, oil and other illegally dumped pollutants along the coast.

Today no one would think of eating a loon. Audubon admitted its flesh was not very palatable, being “tough, rank and dark-coloured,” but said he had seen it much relished by many lovers of good living, especially in Boston, where it was not infrequently served almost raw at the house where he boarded. While in Labrador in July, 1833, he drew the loon in breeding plumage (right) from a fresh specimen he had just shot. The windowless hut in which he worked did not exclude the rain, so to protect his drawing he covered most of it except the section on which he was working. The bird in winter plumage (left) was drawn from a specimen collected some years earlier.

2. Arctic Loon [Black-throated Diver]

Gavia arctica [Colymbus Arcticus]

Order: Gaviiformes

Family: Gaviidae

(Yodel; Long wail; Croak; Short wail, yelp, and splash dive)

Audubon describes the adult in full plumage as extremely rare. He claims to have seen it in Labrador, and well he might have, but the specimens he painted from almost certainly were obtained in England. He makes the curious statement that the young, unlike the adults, spread widely. He states, “One of the most remarkable circumstances relative to this beautiful bird, is the extraordinary extent to which the wanderings of the young are carried in autumn and winter. It breeds in the remote regions of the north from which many of the old birds, it would seem, do not remove far, but the young, as soon as they are able to travel, take to wing and disperse, spreading not only to the greater part of the United States but beyond their southwestern limits.” He wrote as though he knew the young birds well, having seen them commonly on the Ohio, Mississippi, etc. What he probably was referring to was not the young of the Arctic loon but rather the winter plumage of the smaller, slimmer-billed subspecies of the common loon, colloquially known as the “lesser loon.” The latter bird, breeding farther west, has often been a puzzle to birders and has been responsible for a number of erroneous sight records of “Arctic loons” on the Great Lakes and elsewhere. The similar Pacific loon, which breeds across northwestern Canada and Alaska, spends the winter along the Pacific coast.

3. Red-throated Loon [Red-throated Diver] i

Gavia stellata [Colymbus Septentrionalis]

Order: Gaviiformes

Family: Gaviidae

(Plesiosaur duet; Wail; Quack)

The red-throated loon probably has not changed its status much since Audubon’s day. Its arctic breeding grounds are seldom disturbed by human activity, and its offshore wintering range along the coast is quite secure except on those rare occasions when an oil spill claims its victims. Lacking culinary appeal, it is not on the sportsman’s list of desirable game. Audubon wrote, “Its flesh is oily, tough, dark-coloured and disagreeable to the taste, although I saw some mountain Indians feeding upon it at Labrador with apparent pleasure.”

During the late spring on its way north, and during summer on the tundra lakes, the red-throated loon sports a rufous-red throat patch. This is lost in winter, and the bird then closely resembles its larger relative the common loon, except for its much more slender, slightly upturned bill. Its profile is more snaky, and numerous little white specklings on the back give the bird a paler appearance. The most widespread of the loons (or divers as they are called in Britain), the red-throat is holarctic, breeding not only across the North American arctic but also in the tundras of Europe and Asia. Although usually silent much of the year it can be heard at nesting time uttering falsetto wails, falling in pitch, and a series of ducklike “kwuks.” During the winter, after changing its dress, it invades a new environment, the saltwater bays and offshore waters of the coasts, wandering as far south as the Mediterranean, Florida, northwestern Mexico, and China.

Podiceps grisegena [Podiceps Rubricollis]

Order: Podicipediformes

Family: Podicipedidae

(Whinny-Braying duet)

The northern prairie lakes are the summer habitat of the red-necked grebe. Audubon did not visit the “fur countries,” where Dr. Richardson reported these grebes “very common” on every lake with grassy margins. Audubon knew the red-necked grebe only in migration and winter, along the coast from New York to Maine. At Boston (in the market?) he procured several specimens, which may have been the models for his portraits. On the Bay of Fundy he saw “these Grebes already in their spring plumage, it being then the beginning of May.” He wrote: “On one occasion our boat was rowed over an eddy in which a pair had dived in search of food. On emerging they were only a few yards distant; but although several guns were fired at them, they escaped unhurt, for they instantly dived again, passed under the boat at the depth of about a yard, and did not rise until at a safe distance. None of us could conceive how they had managed to elude us, for as they were so near.”

The red-necked grebe, formerly known to birders as Holboell’s grebe, is a transient through the Great Lakes and the upper Mississippi Valley to its coastal wintering grounds that extend from Nova Scotia to Georgia. Only the occasional stray reaches the Gulf coast. Although their main summer range is to the northwest of the Great Lakes, a number of pairs took up residence in the yachting basin at Hamilton, Ontario, placing their nests of waterweed on the floats to which the boats were anchored.

[Podiceps Cristatus]

Order: Podicipediformes

Family: Podicipedidae

Audubon’s inclusion of this old world species in the Elephant Folio and in his Ornithological Biography is a mystery. There is no question that the birds represented here are great crested grebes, but he almost certainly drew them in England from museum specimens. Yet his text tells us explicitly that in migration “A few remain on the lower parts of the Ohio, on the Mississippi, and the lakes in their neighborhood, but the greater number proceed towards the Mexican territories. . . . They pass swiftly . . . in flocks of from seven or eight to fifty or more. . . . I have observed them thus passing in autumn, for several years in succession, over different parts of the Ohio, at all hours of the day. I never saw this species near the sea-coast.” He wrote that when in ponds, they may easily be caught with fishing hooks placed on lines near the bottom. He, himself, had caught two or three in this manner. What bird could Audubon have meant? There is no substantiated record of a great crested grebe ever having been taken or even seen in North America. And yet we find the species included in the works of some of Audubon’s contemporaries—Bonaparte, Swainson, Richardson, and Nuttall. The mystery deepens. However, another species, the western grebe, which ranges east to the upper Mississippi and Missouri valleys, was unknown to Audubon. Could his birds have been that species—or even female mergansers?

Podiceps auritus [Podiceps Cornutus]

Order: Podicipediformes

Family: Podicipedidae

(Pair duet; Call; Chick and adult calls)

Little groups of horned grebes in full spring plumage, with ornamental golden eartufts and chestnut necks, are strikingly beautiful as they float buoyantly on the coastal bays and inland lakes while en route to their nesting lakes on the northern prairies. Strong binoculars will bring out the brilliant red eyes that fascinated Audubon so much. He wrote, “Excepting a species of hawk, I know of no other bird that has the eye of such color, the iris being externally of a vivid red with an inner circle of white which gives it a very singular appearance.” On careful examination of the eyes of other grebes and divers he could not find any with similar eyes and he concluded: “The reason of this strange colouring of the iris, I am unable to conjecture.”

Obviously, at the time he did not know the eared grebe, a similar but more western species, which he drew later (see next plate). It also has red eyes.

The horned grebe is widespread in North America, breeding on marshy lakes in the northwestern part of the continent and wintering along both coasts. The grebes, like many other waterbirds, have benefited from the federal refuge systems of the United States and Canada. Although the refuges are managed ostensibly for ducks, many nongame marsh birds, such as the grebes, have also done well.

In England the horned grebe is known as the Slavonian grebe, an inappropriate name because it is found widely across Eurasia as well as North America.

Podiceps nigricollis [Podiceps Auritus]

Order: Podicipediformes

Family: Podicipedidae

(Male advertising call; Female advertising call; Advertising and other calls from dense breeding area)

The eared grebe was not known to Audubon, who stated that it was “very rare and not found by me in America.” The specimens from which his figures were drawn were loaned to him by Lord Stanley, the fourteenth Earl of Derby, who had received them from North America. This is one of his later drawings, made when he was trying to bring his monumental task to its conclusion.

This small grebe is widespread across Europe and Asia as well as in parts of Africa; but in North America it is confined to the western half of the continent, breeding no farther east than the prairie lakes of western Minnesota and south-central Texas. Very rarely one will stray east to the Great Lakes and even the Atlantic coast; but it is usually overlooked except by the most astute birder, because during the fall and winter it assumes a rather undistinguished plumage, slaty gray and white, much like the winter plumage of the horned grebe with which it easily can be confused. In summer, both species have golden head plumes, but the horned grebe has a chestnut-red neck, the eared grebe a diagnostic black neck, hence its British name, “black-necked grebe.”

8. Pied-billed Grebe [Pied-billed Dobchick] i

Podilymbus podiceps [Podiceps Carolinensis]

Order: Podicipediformes

Family: Podicipedidae

(Wail; Greeting rattle)

With obvious affection, Audubon wrote: “There go the little Dobchicks, among the tall rushes and aquatic grasses that border the marsh. They have seen me, and now I watch them as they sink gently backwards into the deep water, in the manner of frightened frogs. Cunning things! Water witches, as they call you, I clearly see your bills, although you have withdrawn all of you save those parts, and sneak off towards yon great bunch of bullrushes. Well, speed on, and may safety attend you! Nature has granted you means of eluding your enemies, and I am heartily glad to see you have profited by her instructions.”

The pied-billed grebe differs from the other North American grebes in possessing not a pointed bill but one that is rounded and rather chickenlike. Found on ponds and in marshes from coast to coast and from the southern Canadian provinces to Mexico, this is one of the most widely distributed waterbirds in North America but it is easily overlooked because of its retiring habits and drab plumage. The spot across the bill, from which it gets its name, and the black throat are field marks only during the summer months. By winter the bird loses these means of identification. Audubon must have seen the incident he portrayed in this spirited composition, but he has shown one bird in summer plumage, the other in winter.

9. Sooty Albatross [Dusky Albatross]

Phoebetria palpebrata [Diomedia Fusca]

Order: Procellariiformes

Family: Diomedeidae

Audubon wrote in his Birds of America, “The skin from which I made my drawing of this species was prepared by Mr. Townsend, who procured the bird near the mouth of the Columbia River. Of its habits or distribution I am entirely ignorant. Having failed in finding any figure or description of an albatross agreeing entirely with it, I have been induced to consider it as new.” He described it as a new species, the dusky albatross, and gave it the scientific name Diomedia Fusca.

The American Ornithologists’ Union Checklist, which originally listed this subantarctic seabird, now casts doubt on this old record and has relegated it to the hypothetical list. A number of Townsend’s birds reputed to have been taken on the northwest coast have since been questioned. Audubon himself never reached the Pacific in his travels.

The sooty albatross ranges widely through subantarctic seas, nesting on St. Paul, Prince Edward, Marion, and Crozet islands in the southern Indian Ocean and Tristan d’Cunha and Gough in the South Atlantic. Living in the Southern Hemisphere, it seems questionable whether this dark seabird ever reached Oregon, but birds have wings and they use them. The sooty albatross and its closely related form, the light-mantled sooty, are by far the most graceful of all the albatrosses. The harder the gale the better they fly, using the wind, not fighting it.

10. Northern Fulmar [Fulmar Petrel] i

Fulmarus glacialis [Procellaria Glacialis]

Order: Procellariiformes

Family: Procellariidae

(Adult calls at nest ledge)

The saga of this gull-like oceanic glider is a success story. During the last century it did not enjoy the great numbers that it does today in the North Atlantic, especially on the British side. Audubon encountered fulmars off the Newfoundland Banks but had little to say about their habits. He quoted his friend Mr. Selby: “The steep and rocky St. Kilda, one of the western islands of Scotland, is the only locality within the British dominions annually resorted to by the fulmar. The rest of the Scottish and our southern coasts being rarely visited even by stragglers.” Another British contemporary, the Reverend Mr. Scoresby, commented that “The fulmar is the constant companion of the whale fisher.” It has the habit of following the fishing boats to feed on the offal, which made it possible for the fulmar to expand its range from the St. Kilda nucleus to the rest of Britain. In 1952, James Fisher, in his classic work on the fulmar, documented this population explosion. Today hundreds of colonies ring the British Isles.

It seems curious that the fulmar has not proliferated in a similar manner on the North American side of the Atlantic, but it now appears that it is on the verge of doing so. Although its main population is far to the north on Arctic coasts, it recently has bred in Newfoundland. If the trend continues it eventually may become as commonplace in the offshore waters of New England as it now is around the British Isles.

11. Greater Shearwater [Wandering Shearwater]

Puffinus gravis [Puffinus Cinereus]

Order: Procellariiformes

Family: Procellariidae

The name Audubon used, “Wandering Shearwater,” is much more picturesque and really more appropriate, because the other shearwater with which it often associates, Cory’s shearwater, is a bit larger. Neither Audubon nor anyone else at that time knew where this seabird bred. He suspected that it nested along the coast of Nova Scotia: “While sailing around Nova Scotia on my way to Labrador early in June I observed, one evening about sunset, a great number flying from the rocky shores which induced me to think that they bred there. Scarcely one was to be seen during the day and this circumstance strengthened my opinion, as I was aware that these birds are in habit of remaining about their nests at that time.” He found them “unpleasant pets,” for after he caught some and held them in his hands they squirted an oily substance through their nostrils. He soon set them at liberty.

Actually, nearly all of the greater shearwaters in the world nest thousands of miles away in the South Atlantic at remote Tristan d’Cunha. There, on two of the three islands, Nightingale Island and Inaccessible Island, they nest by the million, coming in from the sea and departing in clouds that stagger the imagination. Their migration is a long one that takes their skimming hordes north off the coast of North America as far as Greenland and Iceland, then back again. Their realm is the open ocean, well offshore, and birders seldom see them from land except at favored coastal points such as Montauk on Long Island and Monomoy on Cape Cod.

12. Manx Shearwater [Manks Shearwater]

Puffinus puffinus [Puffinus Anglorum]

Order: Procellariiformes

Family: Procellariidae

(Call in flight)

Until recently this small, black and white shearwater, half the bulk of a greater shearwater, was a rara avis on this side of the Atlantic, an occasional wanderer from its home seacliffs in the British Isles and Iceland. It may have been regular off the Newfoundland Banks in 1831 when Audubon collected the specimen from which he made the pencil sketch that was used as a basis for this plate. Although he had collected the bird in American waters he wrote, “I am unable to say anything of importance respecting its habits as observed by myself.” Recently the Manx shearwater seems to have increased and is seen much more frequently by the pelagic birders who sail between Maine and Nova Scotia. It now breeds in Newfoundland and a pair even has been recorded nesting in Massachusetts. Occasional wanderers are observed south to Cape Hatteras where the trick is to tell them from the very similar Audubon’s shearwater. The latter bird is a bit smaller, has shorter wings, a longer tail, and a more fluttery flight.

13. Audubon’s Shearwater [Dusky Petrel]

Puffinus lherminieri [Puffinus Obscurus]

Order: Procellariiformes

Family: Procellariidae

In the great seagoing family of tube-nosed seabirds, the shearwaters and petrels, there is a small species, Audubon’s shearwater, that wanders northward off our coast as far as Cape Hatteras and rarely to Cape Cod. The birder is not likely to see this bird of subtropical and tropical seas unless he takes a small fishing boat far offshore into the Gulf Stream; it is seldom seen from the beaches, unless storm-driven. Black above and white below, and half the bulk of the larger shearwaters, it can be confused only with the Manx shearwater (previous plate), a more northern, Old World species. Its natal home is on islands in warmer seas—Bermuda, the West Indies, Cape Verde Islands, and the Galapagos. It seldom has been sighted in the Gulf of Mexico in recent years, but Audubon reported great numbers when his ship Delos was becalmed in the Gulf of Mexico near the west coast of Florida when he was sailing from New Orleans to England in 1826. The mate killed four at one shot, and Audubon made a pencil sketch of one that was translated into watercolor several years later. Havell put in a rocky shoreline, which, of course, was inappropriate for Florida.

14. Leach’s Storm-Petrel [Forked-tailed Petrel]

Oceanodroma leucorhoa [Thalassidroma Leachii]

Order: Procellariiformes

Family: Hydrobatidae

(Chatter and purr calls)

Storm petrels are the “Mother Carey’s chickens” of the ancient seamen, little dark birds with white rumps, scarcely larger than swallows, that dance on the water as Audubon has portrayed in his colorplate. Only one species nests on the Atlantic side of North America—Leach’s storm petrel, which Audubon found abundant off the banks of Newfoundland and collected in spite of the giddiness and nausea that never left him when at sea. He obviously knew this species well, stating that it bred on all suitable places from the islands off Mount Desert in Maine to Newfoundland. He noted that its flight differed from that of Wilson’s storm petrel, with broader wheelings and more erratic flappings suggesting a nighthawk, and that it usually did not come close around the vessel as Wilson’s petrel often did. Leach’s petrel is found on both sides of the North Atlantic as well as in the North Pacific. Its nesting colonies are underground, in the turf of offshore islands. Although Leach’s is the breeding-petrel of the North Atlantic, it is less often seen at sea than Wilson’s petrel, which comes to us from the Antarctic; presumably because it feeds much farther offshore. It can be distinguished not only by its more erratic, less fluttering flight, but also by its notched or forked tail.

15. Wilson’s Storm-Petrel [Wilson’s Petrel]

Oceanites oceanicus

Order: Procellariiformes

Family: Hydrobatidae

Wilson’s petrel was named after Alexander Wilson, Audubon’s contemporary. Although breeding in the Antarctic, this dainty seabird ranges into the North Atlantic during the summer, which is then winter in the Southern Hemisphere. Audubon did not know that they nested at the other end of the world, nor did anyone else; he presumed that they bred on some of the small islands, called the “Mud Islands,” situated off the southern extremity of Nova Scotia. He wrote, with seeming authority, “Thither the birds resort in great numbers about the beginning of June and form burrows to a depth of two or two and a half feet in the bottom of which is laid a single white egg.” All of this sounds very positive; actually the birds must have been Leach’s petrels. Audubon’s information (or misinformation) must have come from local fishermen. Wilson was no better informed and stated that this petrel bred in the Bahamas. Actually its breeding grounds are thousands of miles to the south on islands and headlands around the Antarctic Continent, where it treads the water amongst the floating ice, coming in at dusk to fissures in the volcanic rock where it lays its single egg. Audubon, who suffered from seasickness, wrote, “A long voyage would always be to me a continued source of suffering were I restrained from gazing on the vast expanse of the waters and on the ever pleasing inhabitants of the air that now and then appear in the ship’s wake.”

16. British Storm-Petrel [Least Petrel]

Hydrobates pelagicus

Order: Procellariiformes

Family: Hydrobatidae

(Chatter and purr calls)

In August, 1830, becalmed on the banks of Newfoundland, Audubon, according to his account, “obtained several individuals of this species from a flock composed chiefly of Leach’s Petrels, and Wilson’s Petrels.” He thought they were a new species but closer inspection showed them to be the well-known British bird. He was assured that it bred in the sandy beaches of Sable Island off the coast of Nova Scotia. He concludes his account with the contradictory statement, “not observed to breed on the American coast.” Audubon’s record was later discredited because his specimens were no longer in existence, and the species was removed from the North American list. Recently it was reinstated after a specimen was taken at Sable Island, of all places. Could it be that the bird really does breed there occasionally? This seems unlikely as the island is thoroughly worked by field ornithologists these days, but it is quite possible that transatlantic wanderers could reach this isolated sea island from time to time, unobserved because of their close resemblance to the numerous Wilson’s storm petrels. The British storm petrel is smaller than Wilson’s, has shorter legs, and the feet, which lack the yellow webs, do not extend beyond the square tail. The whitish patch on the underwing, a good field mark, is well-shown in Audubon’s drawing. His general account of its habits in his Ornithological Biography is quoted from a British naturalist, Mr. Hewitt.

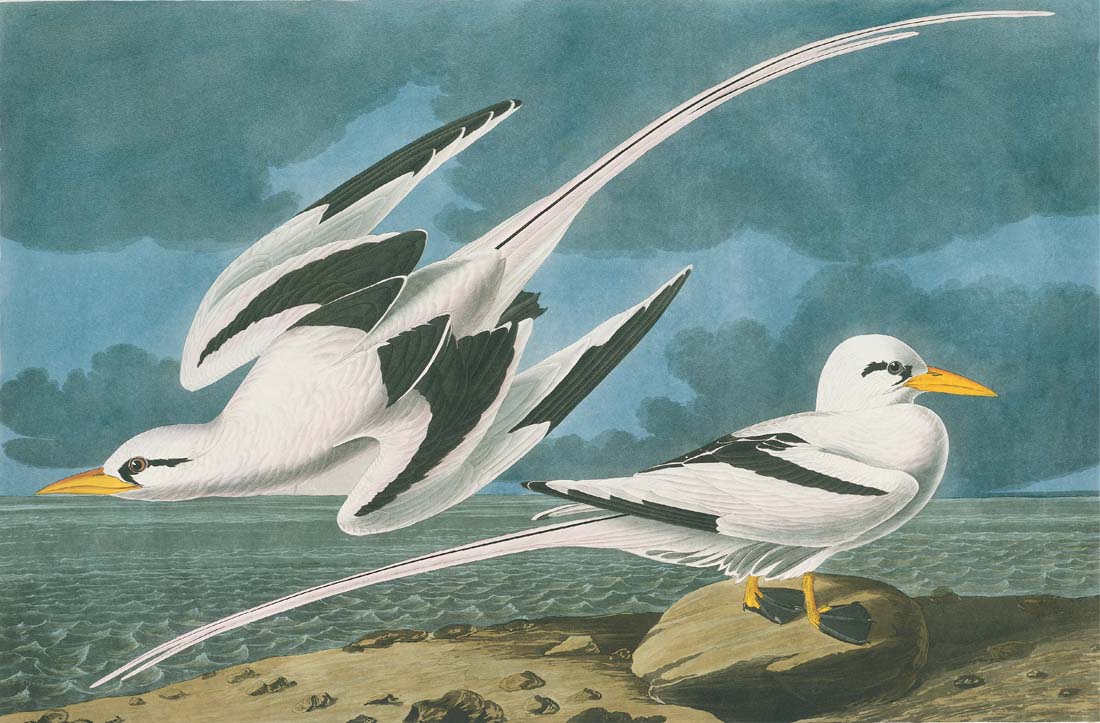

17. White-tailed Tropicbird [Tropic Bird]

Phaethon lepturus

Order: Pelecaniformes

Family: Phaethontidae

The specimens from which Audubon drew the figures in his colorplate were taken in the Dry Tortugas off Key West in the summer of 1832 by Robert Day, Esq., of the United States Revenue Cutter Marion. These two birds were shot out of a flock of eight or ten. Inasmuch as Audubon had never had the opportunity of seeing this species in life he was unable to give much information about it. To this day, the one spot in the United States where tropicbirds are consistently seen is in the Dry Tortugas, but a flock of eight or ten would be most unusual. Usually not more than one or two are ticked off by birders during the course of a visit to those semitropical islets in the Gulf of Mexico. Tropicbirds breed commonly in Bermuda and on many islands scattered through the warmer parts of the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian oceans. Although waifs have been reported after hurricanes as far north in the Atlantic as Nova Scotia, the best chance one has to see this bird in the continental waters of the United States is off the Florida Keys. Tropicbirds fly pigeonlike, on strong, quick wing-strokes over the sea and plunge for food rather like terns. At Christmas Island, south of Java, there is a golden form of this bird that is especially beautiful.

Pelecanus erythrorhynchos [Pelicanus Americanus]

Order: Pelecaniformes

Family: Pelecanidae

(Chick calls)

With justified elation, Audubon wrote, “I feel great pleasure, good reader, in assuring you that our White Pelican, which has hitherto been considered the same as that found in Europe, is quite different. In consequence of this discovery I have honored it with the name of my beloved country, over the mighty streams of which, may this splendid bird wander free and unmolested.” It was well known to him that this majestic bird nested far to the northwest in the “fur countries,” but he was puzzled as to why at that same season he saw some along the Gulf of Mexico. His friend the Reverend Bachman of Charleston stated that it formerly bred on the sandbanks of South Carolina. He saw a flock on the bird banks off Bull’s Island on the first of July, 1814, and was under the impression that they had eggs on one of those banks. Audubon, thinking about this, wrote, “Reader, I have thought a thousand times perhaps that a portion of the myriads of ducks, geese and other kinds which leave for higher latitudes were formerly in the habit of remaining and breeding in every section of the country that was found to be favorable. It seems to me that it is now on account of the constantly increasing numbers of our hostile species that these creatures are urged to proceed towards wild and uninhabited parts of the world where they find that security from molestation necessary to enable them to rear their innocent progency.” Although in his early years Audubon was “in blood up to his elbows,” he obviously became more reflective and compassionate later on.

Pelecanus occidentalis [Pelicanus Fuscus]

Order: Pelecaniformes

Family: Pelecanidae

(Chick calls)

The seriocomic pelicans with their accordion-pleated pouches are the delight of every tourist who visits the beaches of Florida or California. The most popular pelicans of all are perhaps those that make the piers around Tampa and St. Petersburg their headquarters, patiently sitting on their posts until someone offers a handout. At once profoundly dignified, as birds of such ancient lineage should be, they are at the same time masters of deadpan clowning, particularly when two or three birds contend for the same fish. These pelicans that prefer begging to an honest living probably nest with the hundreds of their kind that resort to the mangrove islands well out in Tampa Bay. Many are accidentally hooked or tangled in the lines of fishermen and become sorely injured. They are rounded up by the Suncoast Seabird Sanctuary in St. Petersburg where hundreds of pelicans are rehabilitated yearly.

Pelicans fly in orderly lines, close to the water, flapping, then sailing, each bird taking its cue from the bird in front of it, as if they were playing follow-my-leader. Fishing, the big birds fly aloft, spot the schools of small fry, and, facing downwind, pull their wings back and plunge beak-first with a grand splash. The brown pelican, which is the state bird of Louisiana, has a wingspread of six and a half feet. It is strictly coastal, whereas the white pelican, with a wingspread of nine feet, nests far inland in the western half of the continent.

20. Brown Pelican [immature] i

Pelecanus occidentalis [Pelicanus Fuscus]

Order: Pelecaniformes

Family: Pelecanidae

(Chick calls)

How different was the attitude toward pelicans when Audubon wrote, “I procured specimens at different places but nowhere so many as at Key West. There you would see them flying within pistol shot of the wharfs, the boys frequently trying to knock them down with stones.” Today, when a pelican appears on a Florida dock, people throw fish, not stones. Audubon noted that “its numbers have been considerably reduced, so much indeed that in the inner bay of Charleston, where twenty or thirty years ago it was quite abundant, very few individuals are now seen.” He found the pelicans “year after year retreating from the vicinity of man.” He feared they would be “hunted beyond the range of civilization.”

There is no doubt that the brown pelican recovered some of its numbers since the early years of this century when Theodore Roosevelt created the first federal refuges and set aside an island on the east coast of Florida for pelicans. In the late fifties and early sixties calamity from another source struck. Toxic poisons in the food chain, presumably from contaminants pouring into the Gulf of Mexico, completely wiped out the pelicans in Louisiana and Texas. In 1968 they were reintroduced into Louisiana with birds from colonies that still persisted in Florida. They are now again widespread in the Gulf.

This young pelican, painted in New Orleans, was one of Audubon’s mixed medium efforts: a combination of pencil, watercolor, pastel and oil.

21. Brown Booby [Booby Gannet] i

Sula leucogaster [Sula Fusca]

Order: Pelecaniformes

Family: Sulidae

(Landing call; Agonistic call)

There can be no doubt that this bird of the pantropical oceans nested commonly in the Dry Tortugas off Key West when Audubon visited these sandy islets in 1832. He wrote, “About eight miles to the northeast of the Tortugas Lighthouse lies a small sandbar called Booby Island on account of the number of birds of this species that resort to it during the breeding season. . . . We landed, and sent the boat to some distance, the pilot assuring us that the birds would return. . . . As they approached we laid ourselves in the sand and although none of them alighted we attained our object for in a couple of hours we procured thirty individuals, finding little difficulty in bringing them down as they flew over us. The same day we landed on another island named after the noddy. There also we found a great number of boobies. They flew close over our heads eyeing us with dismay. They were perched in the top branches of the trees on which they had nests and here again we obtained as many as we desired.”

Audubon objected to the name “booby.” He wrote, “To me the word is utterly inapplicable to any bird with which I am acquainted. . . . it is only when birds of any species are unacquainted with man, that they manifest that kind of ignorance or innocence which he calls stupidity.”

One can still see the occasional brown booby perched on the buoys and channel markers off the Dry Tortugas or on the oil rigs elsewhere off the coast.

22. Northern Gannet [Common Gannet] i

Morus bassanus [Sula Bassana]

Order: Pelecaniformes

Family: Sulidae

(Nesting colony)

This goose-sized seabird, snow white with black primaries, scales over the waves and plunges headlong for fish. It is much larger than any gull, with a pointed tail and a larger, more pointed bill. Gulls have shorter wings and more fan-shaped tails. The pointed-at-both-ends look identifies even the brown young gannets at a distance.

The bulk of the gannets in the North Atlantic live on the European side, mostly on rocky islets and cliffs around Scotland and Iceland; but there are six healthy colonies on the North American side, located off Newfoundland and in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Audubon was distressed that he could not land with his party of young stalwarts, including his son, at the breeding place in the Gulf of St. Lawrence known as Gannet Rock. A fearful storm arose just as his boat approached the rock. But while anchored there he spent the greater part of two days painting the birds and the background. The pilot, a Mr. Goodwin, stated that “the Labrador fishermen and others who annually visit this extraordinary resort of the gannets for the purpose of securing their flesh to bait their codfish hooks, ascend armed with heavy, short clubs in parties of eight or more and at once begin their work of destruction.” Mr. Goodwin added that he had visited Gannet Rock ten seasons in succession for such purposes and that on one of those occasions six men destroyed 540 gannets in about an hour, after which most of the living birds left the immediate neighborhood.

23. Great Cormorant [Common Cormorant] i

Phalacrocorax carbo

Order: Pelecaniformes

Family: Phalacrocoracidae

It is quite probable that the great cormorant, the common large cormorant of Europe, was more numerous on this side of the Atlantic during Audubon’s day. He describes its nesting colonies in Labrador and states that it is “abundant in winter around the islands of the Bay of Boston and on the coasts of Massachusetts and Maine, as well as on the coasts of the Bay of Fundy and along the shores of Nova Scotia.” It may have suffered a massive decline as did the double-crested cormorant, resulting from persecution by fishermen who regarded it as a competitor. Audubon reported that he had seen it exposed for sale in the New York market but that he regarded the flesh dark, tough, and fishy, and the eggs not too pleasant. He added, “It is seldom that either are eaten even by epicures.”

There is no question that this species is increasing. It now occurs regularly south to New Jersey and sometimes farther. It has been noted as a straggler as far south as Florida. A cormorant in winter anywhere on the New England coast is most likely to be this species. The smaller, double-crest usually leaves for more southern latitudes. One of the most accessible places to observe this cormorant is at the small lighthouse just above the Jamestown Bridge on Narragansett Bay in Rhode Island. If one watches while driving over the bridge, one may see the iron railings of the small light crowded with dozens of upright black figures.

24. Double-crested Cormorant [Florida Cormorant] i

Phalacrocorax auritus [Carbo Floridanus]

Order: Pelecaniformes

Family: Phalacrocoracidae

(Calls at roost)

Audubon described this southern race of the double-crested cormorant, which breeds from Virginia and the Carolinas to Florida, as a distinct species. More recently, taxonomists have agreed that it should be lumped conspecifically with the northern form (see next account).

In reading Audubon’s accounts of his travels we are struck with the contrast between people’s attitudes toward birds in those days and the attitudes of today. In April, 1832, Audubon and his party, bent on slaughter, visited a colony of cormorants in the Florida Keys. “A great number stood on their nests and the branches as if gazing upon beings strange to them; but alas they soon became too well acquainted with us; for the discharges from our guns committed frightful havoc among them. The dead were seen floating on the water, the crippled making toward the open sea, while groups of a hundred or more swam about a little beyond reach of our shot, awaiting the event, and the air was filled with those whose anxiety to return to their eggs kept them hovering over us in silence. In short time the bottom of our boat was covered with the slain; and we may now intermit the work of destruction.”

Audubon reported that the Indians and the blacks killed the young when they were nearly able to fly and, after skinning them, salted them for food. They were offered for sale in New Orleans where the poorer people made gumbo soup of them.

25. Double-crested Cormorant i

Phalacrocorax auritus [Phalacrocorax Dilophus]

Order: Pelecaniformes

Family: Phalacrocoracidae

(Calls at roost)

Cormorants are familiar sights along the coasts, their long gooselike ribbons etched against the sky as they travel to and from their fishing grounds. There is no evidence that Audubon found this race of the double-crested cormorant nesting south of the Bay of Fundy. It may well have been absent from the entire coast of New England; certainly no colonies were known in Maine in the decade 1880 to 1890. A very few bred in the mid-nineties, then dropped out again, perhaps because of raids by fishermen. It is suspected that they started to nest again about 1925. No longer used as bait by the fishermen, their build-up was explosive. By 1930 there were hundreds; by 1944 at least 10,000 bred on islands off the Maine coast. This increase has continued until they now have outpost colonies as far south as islets in Long Island Sound off eastern Connecticut. It may be only a matter of time before the northern population of double-crests joins its southern relatives in southeastern Virginia (which, of course, it does in winter). The double-crested cormorant is the only one of the several North American cormorants that is not confined strictly to salt water. It is widespread through some of the lake regions of the interior but has not shown any corresponding increase there; rather a decline in some areas.

From left to right:

26. Pelagic Cormorant [Violet-green Cormorant] i

Phalacrocorax pelagicus [Phalacrocorax Resplendens]

(Calls at nest)

Brandt’s Cormorant [Townsend’s Cormorant] i

Phalacrocorax penicillatus [Phalacrocorax Townsendi]

(Kauk call)

Order: Pelecaniformes

Family: Phalacrocoracidae

The two cormorants shown here were sent to Audubon by Dr. Townsend, who procured them at Cape Disappointment at the mouth of the Columbia River in October, 1836. Inasmuch as Audubon believed them both to be new species he described them, naming one in honor of its discoverer and the other after its handsome plumage. Beyond that he had no knowledge of the distribution or habits of either species. Although he drew them together on this plate, he later separated them in his octavo The Birds of America.

The pelagic cormorant, which ranges along the Pacific coast from British Columbia to Baja California, so impressed Audubon by its deep violet and green iridescence that he named it “resplendens.” Although it might at times nest in loose association with other cormorants, it prefers the more inaccessible ledges and vertical cliff faces where it builds a nest of seaweed in which it lays four or five pale bluish eggs.

Brandt’s cormorant, which shares the same range along the Pacific coast from Vancouver Island to Baja, is the more gregarious of the two. It seems to prefer the open tops of small islands, shoulders of rocks, and grassy slopes. It is loath to leave its eggs unattended if predaceous western gulls are around.

27. Anhinga [Black-bellied Darter] i

Anhinga anhinga [Plotus Anhinga]

Order: Pelecaniformes

Family: Anhingidae

This gaunt resident of southern swamps goes by various names, such as “snakebird,” “water turkey,” and “darter”; but anhinga is the name the birders use. To this list of pseudonyms Audubon adds “Grecian Lady” (southern Florida), “cormorant” (South Carolina), “bec-à-lancette” (New Orleans), and “water crow” (Mississippi delta). Superficially the anhinga is a bit like a cormorant, but far more slender, with a snakier neck and a much longer tail. Much of the day it sits motionless, sunning itself with wings half spread, suggesting laundry hung out to dry. Dropping to the water it swims low, often with just the head and neck above the surface. Sinking beneath the murky water it looks not unlike a snake, sliding this way and that amongst the submerged water plants. On the wing it is swift and can soon rise to a great height, where it soars in hawklike circles. Males are black bodied with large silvery white wing patches; females have a buffy neck and chest.

Our anhinga has a wide range in the wooded swamps, rivers, and ricefields of the southeastern states and thence through Central and South America to northern Argentina. Similar anhingas or “darters” are found widely in the Old World tropics.

28. Magnificent Frigatebird [Frigate Pelican] i

Fregata magnificens [Tachypetes Aguilus]

Order: Pelecaniformes

Family: Fregatidae

(Male display; Juvenile begging)

The “man-o-war-bird,” as it was formerly called, may have been more numerous a century and a half ago, if we can credit Audubon’s account written in 1835. He claimed that it resided “constantly on and about the Florida keys, where it breeds in vast numbers on trees.” However there are discrepancies in his account that suggest he may have been mistaken about the nests. It is mostly a nonbreeding summer visitor to coastal Florida and the Gulf Coast, and it was only recently that an active nesting colony was found near Key West in the Marquesas Keys.

An excellent place to observe these “marine vultures” is Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas. Although Audubon observed very few around the old fort, there are usually at least 200 or 300 in the neighborhood, many of which soar for hours on the thermals or updrafts generated by the bastions of the great stone buildings.

The magnificent frigatebird, or “man-o-war-bird,” has the longest wing span in relation to its weight of any bird. The body weighs scarcely three pounds whereas the wingspan exceeds seven feet. Master of the air, it normally does not swim but snatches up jellyfish, squid, and other food from the surface of the water; or it may take fish by force from terns or boobies. The long forked tail is often folded in a long point giving the bird the aspect of a witch riding a broomstick. The all black male has a red throat patch that can be inflated like a huge red balloon.

Ardea herodias

Order: Ciconiiformes

Family: Ardeidae

(Call; Call; Chick call)

In his determination to figure every bird life-size in his Double Elephant Folio, Audubon was forced to contrive some very contorted poses, especially when portraying large birds with long necks and/or long legs. In this portrait of a great blue heron he has solved the problem of fitting the gangling bird onto the page by dropping its head in a graceful sweep to its feet.

Four feet tall, the statuesque great blue heron stands motionless in the shallows, waiting until a fingerling or a frog ventures close enough to spear with a lightning thrust. From coast to coast, and from the Gulf of St. Lawrence to the Gulf of Mexico, this gaunt wader is familiar to people who live near the water. Many call it a “crane,” but cranes are more restricted to the inland prairies and always fly with their necks stretched full length. The great blue heron in flight pulls its neck into a comfortable loop, tucking its head back to its shoulders. Both birds have a wingspread equal to that of an eagle.

High in the tall trees of swampy woodlands herons build their rickety platforms of sticks. Scores and sometimes hundreds gather from miles around to form a single heronry, for like many other waterbirds they find security in numbers. They are no longer preyed upon by human carnivores as they were in Audubon’s day. He admitted that the young in the nest afford tolerable eating, but not the adults: “I would at any time prefer a crow or a young eagle.”

30. Great Blue Heron [Great White Heron] i

Ardea herodias [Ardea “occidentalis”]

Order: Ciconiiformes

Family: Ardeidae

(Call; Call; Chick call)

Prior to Audubon’s visit to Indian Key in Florida in April, 1832, this large white form of the great blue heron was undescribed. He regarded it as a new species to which he gave the scientific name Ardea Occidentalis. It is now believed to be not a valid species but simply a color morph of the great blue. An intermediate form, known as “Wurdemann’s” heron, is also known. The great whites may have been more abundant formerly because Audubon wrote that “they flock at their feeding grounds sometimes a hundred or more, being seen together.” There was a period in the mid-1930s when they were greatly decimated by a hurricane that swept through the Florida Keys. Since then they have recovered and are again a common sight throughout the Keys, standing out with startling whiteness against the jade-green waters of the Gulf. Whereas in earlier times, when they were hunted, they were understandably wary, some are now so accustomed to people that they can be seen loitering around the piers and boat docks.

Audubon caught several that were kept in captivity by his friend Bachman. He wrote, “On many occasions, they struck at chickens, grown fowls and ducks, which they would tear up and devour. Once a cat which was asleep in the sunshine, on the wooden steps of the veranda, was pinned through the body to the boards and killed by one of them. At last they began to pursue the younger children of my worthy friend, who therefore ordered them to be killed.”

Butorides striatus [Ardea Virescens]

Order: Ciconiiformes

Family: Ardeidae

(Alarm call; Kuk-kuk-kuk call; Advertising call)

This small, dark heron is the most generally distributed member of its family in the United States and the one most likely to be seen around little wooded ponds and streams in the northern parts of the country. At close range it reveals a rich chestnut neck and greenish-yellow or orange legs. In strong light its somewhat iridescent upperparts may seem more blue than green, leading some inexperienced observers to believe they have discovered a little blue heron. Alarmed by close approach, it elevates a shaggy crest and flies off with a loud skyow or skewk. Airborne, it looks quite black and crowlike, but it flies with slower, more arched wing-beats than a crow.

Audubon has shown a green-backed heron plucking a luna moth from the leafblade of a marsh plant, a rather unlikely incident because the ethereal green moth is usually to be found in a woodland environment. However, moths have wings and could be encountered occasionally in an atypical situation. Audubon, with pardonable artistic license, has chosen to show the bird animated in this manner.

Whereas most other herons breed in colonies, this species tends to be a loner, usually nesting in the privacy of some thick grove or in an orchard, but there are places, particularly near the coast, where several pairs might nest together.

32. Little Blue Heron [Blue Crane or Heron] i

Florida caerulea [Ardea Caerulea]

Order: Ciconiiformes

Family: Ardeidae

“The heronries of the southern portions of the United States are often of such extraordinary size as to astonish the passing traveler,” Audubon wrote. “I confess that I myself might have been sceptical had I not seen with my own eyes the vast multitude of different species breeding together in peace in certain favourable localities.”

Scattered among the immaculate egrets are the little blue herons, dark, smoky blue-gray birds with maroon necks. Immature little blues are quite as white as egrets and, at a distance, are easily mistaken for them. During the transition from white immaturity to blue adulthood they are boldly pied with white and dark, and at New Orleans, according to Audubon, were called “foolish egrettes,” “on account of their unusual tameness.” Such a bird is shown in the background of this painting that represents a scene in the South Carolina lowcountry.

This species, though not pressured as relentlessly as the egrets, suffered grievously at the hands of plume hunters and was greatly diminished by the turn of the century before protective laws were put in effect. By the 1920s it began to show a definite comeback and postbreeding wanderers, especially the white immature birds, were again to be seen in the northern states. Today the little blue nests farther north than it was known to nest in earlier times. Breeding colonies now exist locally as far north as southern Maine and the Great Lakes.

33. Reddish Egret [Purple Heron] i

Egretta rufescens [Ardea Rufescens]

Order: Ciconiiformes

Family: Ardeidae

The reddish egret is dimorphic, displaying two color phases; one white, the other purplish blue. Audubon was confused about this and thought the white birds were immatures, the purple ones fully adult. He was aware that some white birds actually bred but thought they eventually changed to blue. He mentioned seeing as many as a hundred in the Keys but was told that although this species was still plentiful in Florida there had been many more when the Keys were first settled. He wrote, “I was present when a person killed 28 in succession in about an hour, the poor birds hovering above their island in dismay and unaware of the destructive power of their enemy.” It was inevitable that the reddish egret eventually would be lost to the U.S. avifauna, so in the 1930s the National Audubon Society made a special effort to protect this endangered species with wardens in Florida and on the Texas coast where it also had been much diminished. Today it is slowly repopulating its former range and is found not only throughout the Keys but well up along both coasts of Florida as well. The coastal Texas population also has spread and there are now at least three breeding colonies in Louisiana.

When feeding, the reddish egret has a habit of dancing with wings partly spread, lurching about as though half drunk. The pink color at the base of the bill is the best field mark by which it may be separated from other white or bluish herons.

34. Great Egret [White Heron] i

Casmerodius albus [Ardea Egretta]

Order: Ciconiiformes

Family: Ardeidae

(Call; Chick call)

Prior to nesting season this large, elegant white heron develops a bridal train of long white plumes, an adornment that brought a price upon its head and almost resulted in its extermination by the beginning of this century. Audubon wrote, “The long plumes of this bird being in request for ornamental purposes, they are shot in great numbers while sitting on their eggs, or soon after the appearance of the young. I know a person who, on offering a double barreled gun to a gentleman near Charleston, for one hundred white herons freshly killed, received that number and more the next day.”

Such slaughter, were it continued, would have resulted in the extinction of this species, as well as the snowy egret and several other herons. Outrage on the part of conservationists saved the egrets just in time. Wardens of the National Audubon Society guarded the rookeries, and these long-legged glamour birds made a recovery—slow at first but eventually repopulating their former range. Today the great egret nests north on the coastal plain to Massachusetts and in the Mississippi Valley to Minnesota. There is a postbreeding dispersal during the summer months to the Great Lakes and southern Canada.

Audubon solved space limitations in this composition by presenting the bird with its neck deeply curved. The mud chimneys of crayfish are quite typical of the marshy Gulf coast habitat of this species, but Havell, the engraver, added a horned toad, an inappropriate reptile of arid regions farther west.

35. Snowy Egret [Snowy Heron] i

Egretta thula [Leucophoyx Thula]

Order: Ciconiiformes

Family: Ardeidae

The snowy egret, “the heron with the golden slippers,” has become the proudest symbol of the National Audubon Society, the great conservation organization that has adopted John James Audubon as its patron saint. At the beginning of this century, the little snowy, loveliest of all American herons, was on the way out. Its exquisite plumes, called “aigrettes” by the trade, were worth $32 an ounce, twice their weight in gold. Every heronry was ferreted out and destroyed. As the birds bore these nuptial sprays only at nesting time, the young birds, bereft of their parents, perished too, and the stench of death hung heavy over every colony. Where there had been hundreds of thousands of egrets in our southern states there soon remained but a few hundred. The National Audubon Society fought for plumage laws, and to meet the emergency hired wardens. The first Audubon warden in South Florida, Guy Bradley, was shot by plume hunters near Cape Sable in 1905. A marker which stands where his body washed ashore reads “Faithful unto death.” Under protection the egrets and all the other long-legged waders have made a spectacular comeback. Today snowies nest north to coastal New England, beyond their known ancestral range.

Audubon chose for his background a rice plantation in the Carolina “Low Country.” We wonder whether the small figure in the ditch at the right was meant to be Audubon himself, carefully stalking the bird that is to be immortalized as his model.

36. Tricolored Heron [Louisiana Heron] i

Egretta tricolor [Ardea Ludoviciana]

Order: Ciconiiformes

Family: Ardeidae

“Delicate in form, beautiful in plumage and graceful in its movements, I never see this interesting Heron, without calling it the Lady of the Waters,” wrote Audubon. “Its measured steps are so light that they leave no impression on the sand, and with its keen eye it views every object around with the most perfect accuracy.”

This, the most slender of all herons, is readily identified by its white belly, contrasting with its dark neck and upperparts. It is found widely in swamps and marshes from our eastern seaboard states to Brazil.

Although the tricolored heron lacks the white plumes of the egrets, once so coveted by the millinery trade, it was shot nevertheless simply because it was a bird. Audubon commented, “At the cry of a wounded one they assail you in the manner of some gulls and terns. They may be shot in great numbers by any person fond of such sport.”

Today that attitude no longer prevails and, whereas it was known to Audubon no farther north than southern New Jersey where it was rare, it now nests in small numbers north to Long Island, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and even southern Maine.

The background of this portrait, painted by George Lehman, looks more like an idealized landscape in the Central or South American tropics than any scene in the Florida Keys, which it allegedly represents.

37. Black-crowned Night Heron [Night Heron or Qua Bird] i

Nycticorax nycticorax [Ardea Nycticorax]

Order: Ciconiiformes

Family: Ardeidae

At dusk on the marsh a flat quok or quark announces the arrival of the night heron from its hidden roost, perhaps several miles distant, where it has spent the day. Its silhouette against the evening sky is unmistakably that of a heron, but it is shorter-legged and stockier.

In recent years the large night heron colonies on Long Island and elsewhere in the northeast suffered a serious drop in numbers for reasons that are not fully understood. It has been suggested that the DDT syndrome of the 1950s and 1960s might have been responsible for the decline, but if so why should the snowy egret, cattle egret, and glossy ibis be prospering as never before? All three of these long-legged waders that share the night heron’s marshes are now breeding in New England where they were unknown at the beginning of this century. Perhaps it has to do with their food preferences.

The black-crowned night heron is not peculiar to North America. It is a familiar inhabitant of marshes and shores from southern Canada to Tierra del Fuego and the Falklands where a dark race can be seen standing on the tidal rocks in the company of Magellanic penguins. It is also widespread in suitable terrain in Europe, Asia, Africa, and some of the Pacific Islands.

38. Yellow-crowned Night Heron [Yellow-crowned Heron] i

Nycticorax violaceus [Ardea Violacea]

Order: Ciconiiformes

Family: Ardeidae

Audubon stated, “The Yellow-crowned Heron, which is one of the handsomest species of its tribe, is called ‘Cap-cap’ by the Creoles of lower Louisiana in which country it is watched and shot with great eagerness on account of the excellence of its flesh. Like the Night Heron, this species may be enticed near by imitating its cries. It is in the evening and at dawn that they are chiefly obtained.”

He never met this bird farther north than New Jersey or Natchez on the Mississippi, so one can only conclude that there has been a very considerable range extension since then. Although not as common as the black-crowned night heron, seldom nesting in colonies, it now breeds locally north to Massachusetts and in the Mississippi Valley to Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan.

The “violet night queen” (a translation of its former generic name Nyctanassa) lives in cypress swamps, mangroves, bayous, marshes, and along wooded streams in eastern North America and the northern and eastern parts of South America; but in the Galapagos Islands where an isolated population lives it can be seen stalking red crabs amongst the lava rocks. Its note, a sharp quark, is higher pitched than the quok of the black-crowned night heron. The immature bird is very similar to the speckled young black-crowned, but stands taller and, in flight, the legs extend well beyond the tail.

Ixobrychus exilis [Ardea Exilis]

Order: Ciconiiformes

Family: Ardeidae

(Song; Tut call; Tutu-tut-tut call)

This tiny, elusive heron is scarcely the size of a meadowlark, and much thinner. Audubon tried an experiment with a live least bittern that a lady brought to him in her apron. He placed two books erect, an inch apart, on a table. The bird easily walked between the two books without moving either of them. Although a least bittern would seem too wide to pass through such a narrow space, it apparently can constrict its body, an ability that enables it to move without hindrance through the dense reeds and cattails.

Were it not for its song, a low, muted cuckoolike coo-coo-coo, we might not suspect the presence of this little heron in the marsh. When discovered it may “freeze” or slowly melt into the reeds, relying on its protective coloration to escape notice. When pressed, it reluctantly takes to the air, displaying large buff wing patches. After flying but a short distance, it drops in again to play hide and seek. Least bitterns share the marshes with the rails, which are even more elusive. None of the rails show the conspicuous buff wing patches when they fly.

The two adult males in the plate were painted in Philadelphia in 1832; the young bird at the left, drawn twelve years earlier, was cut out and pasted on the finished composition. Audubon often used this procedure to save time.

Botaurus lentiginosus [Ardea Minor]

Order: Ciconiiformes

Family: Ardeidae

(Male pump-er-lunk song)

The “pumping” of the bittern is one of the strangest sounds of the marsh; a slow, deep oong-ka-choonk, oong-ka-choonk, oong-ka-choonk. To some it hardly seems birdlike but rather a hollow muffled sound that must have failed to register on Audubon’s obviously poor ears. He wrote, “Although I have killed and assisted in killing a considerable number at various times of the year, I never heard their booming or love notes; or if I have, I did not feel assured that the sounds which reached my ears were those of the American Bittern. This may probably appear strange considering the many years I have spent in searching our swamps, marshes, and woods, yet, true it is that in all my rambles I had not the good fortune to come upon one of these birds sitting on its eggs either among the grass or rushes or on the branches of low bushes where, I have been informed, it builds.” He reported that “It is common in the markets of New Orleans where it is bought by the poorer classes to make gumbo soup.”

Marshes and rushy margins are the bitterns’ habitat, where its streaked brown pattern blends so closely with the surrounding dead reeds that if the bird does not take flight it is scarcely noticed. Although it has a wide breeding range, from the northeastern parts of the Atlantic coast across Canada and the northern states to the Pacific, it is very local and seems to be declining. Audubon credits this drawing to his son John.

Mycteria americana [Tantalus Loculator]

Order: Ciconiiformes

Family: Ciconiidae

(Nestling calls)

Until recently the wood stork went by the name of wood ibis because of its curved bill; however, it is a true stork, the only one in North America. Less trusting than the friendly storks that nest on rooftops in European hamlets, our wood stork shuns civilization, withdrawing to the deep swamps of the south. It must have been a far more numerous bird in Audubon’s day. He describes flocks of thousands passing over the woods in a line more than a mile in depth. He wrote, “I am quite convinced we have not in the United States a more shy, wary, and vigilant bird.” Understandable, because in those freewheeling days wood stork were fair game for the pot. Audubon, however, thought they were tough, oily, and not fit for food; “The negroes, however, eat them, having previous to cooking them, torn off the skin as they do with pelicans and cormorants.” He added, “Many of the negroes of Louisiana destroy these birds when young for sake of the oil which they use in greasing machines.” Because of such persecution for food and for sport the wood stork became much reduced in numbers, and this, added to deterioration of their environment, made it a species that, although not endangered, was vulnerable. The National Audubon Society has been safeguarding the few known colonies of this spectacular bird, of which the most publicized is the Corkscrew Rookery in south-central Florida where visitors may watch the birds from a boardwalk.

Plegadis falcinellus [Ibis Falcinellus]

Order: Ciconiiformes

Family: Threskiornithidae

The glossy ibis is an Old World species that seems to have colonized North America in relatively recent times. It was first recorded within the limits of the United States by Mr. George Ord of Philadephia and was described by Alexander Wilson, who stated, “On the 7th of May of the present year, 1817, Mr. Thomas Say received from Mr. Ord of Great Egg Harbor a fine specimen which has been shot there.” Subsequently, according to Mr. Nuttall, specimens were occasionally exposed for sale in the markets of Boston.

Audubon encountered this species only once, the male bird figured in his plate, “procured in Florida near a wood-cutter’s cabin, a view of which is also given.” Later he saw flocks that he thought were this species in Texas. In reality they were the very similar white-faced ibis.

Prior to 1936 the largest known colony of glossy ibises comprised about 27 nests at Lake Orange in Florida. That year a very large concentration was reported in Lake Okeechobee and substantiated by the present author (R.T.P.). This colony, which numbered many hundreds, probably was the nucleus from which the bird spread up the Atlantic coast until it is now found in many sizable colonies as far north as New Jersey and even in scattered groups to coastal Maine. It is also expanding its range westward, meeting the white-faced ibis in Louisiana. A very recent arrival in North America, it must have come from overseas in much the same manner as the fulvous whistling duck and the cattle egret.

Eudocimus albus [Ibis Alba]

Order: Ciconiiformes

Family: Threskiornithidae

(Calls at roost)

The white ibis, long a favorite ward of the National Audubon Society, probably enjoys much the same distribution in the southern states as it did formerly—from the Carolinas south through Florida and westward to Texas. Some of the colonies are very large, particularly those in the Everglades and along the St. Johns River where incoming birds stream through the sky like long white ribbons against the blue. At other times, like wood storks, they rise to great heights where they circle on the thermals, then glide down with great speed to the treetops or back into the marsh.

In earlier days, until the beginning of the present century, white ibises were fair game and were shot for food; but this is now history. The fact that we still have so many ibises is a tribute to our laws and the dedicated efforts of Audubon wardens.

Occasionally a white ibis wanders northward to New Jersey or farther; but this species seldom indulges in postbreeding wanderings as some of the southern herons and egrets do.

Audubon wrote, “The Creoles of Louisiana call this species ‘Bec croche’ and also ‘Petit Flaman,’ although it is generally known by the name of ‘Spanish Curlew.’ The flesh is extremely fishy, although the birds are often sold in our southernmost markets and are frequently eaten by the Indians.”

Eudocimus ruber [Ibis Rubra]

Order: Ciconiiformes

Family: Threskiornithidae

The scarlet ibis, a South American species closely allied to the white ibis, was supposed by Alexander Wilson to be not uncommon in the southern parts of the United States. Audubon took issue with this, stating that he had seen the species only once—three birds at Bayou Sara in Louisiana on the 3rd of July, 1821: “They were traveling in a line, in the manner of the white ibis, above the tops of the trees.”

In his journal he wrote, “My drawing of the adult male, and that of the immature bird, were made from specimens procured beyond our limits.” He added, “As I have not had opportunity of observing them I judge it better to abstain from offering any remarks on the subject.”

It is quite likely that individuals seen on rare occasions in the Gulf states are bona fide stragglers, but the pinkish birds sometimes reported are almost certainly zoo escapes that have lost their color in captivity. A few years ago some scarlet ibis eggs flown from South America were placed in the nests of white ibises in a Miami park. These were hatched and successfully reared to adulthood. Later some hybrids resulted from this avicultural experiment.

Ajaia ajaja [Platalea Ajaja]

Order: Ciconiiformes

Family: Threskiornithidae

(Adult alarm call; Nestling cheep)

Shell pink with deep carmine “drip” along its shoulders, the roseate spoonbill is one of the most breathtaking of the world’s weird birds. Living in the mangrove swamps, it wades the marl flats, rhythmically swinging its spatulate bill from side to side, sifting out killifishes, prawns and other small water creatures.

In Audubon’s day spoonbills were numerous in the Gulf states from Florida to Texas, and although their rosy wings were sold commercially for fans in St. Augustine, they did not interest plumage hunters as much as the egrets whose filmy nuptial sprays were in demand. But they were big pink birds that lived with the egrets and so were tempting targets. In the years that followed, particularly after the Civil War, they rapidly disappeared, and before the end of the century not one still bred in Texas and perhaps not two dozen in Florida. If it were not for the fact that some spoonbills still survived south of the border, the species surely would have followed the passenger pigeon and the Carolina paroquet into the void of extinction. During the 1920s little flocks wandered across the Mexican border into Texas, and when they tried to nest the National Audubon Society extended a helping hand by sending wardens to watch over them. By the 1940s there were thousands of spoonbills in Texas. The Florida birds also have done better during recent years, especially in the Florida Keys and Everglades National Park, and now are extending well up the West coast.

Phoenicopterus ruber

Order: Phoenicopteriformes

Family: Phoenicopteridae

Today, if one sees a flamingo in Florida, there is always the question whether it was a bona fide traveler from the Bahamas or an escape from Hialeah, Busch Gardens, or one of the other captive colonies in Florida. However, in Audubon’s day Hialeah did not exist nor did Busch Gardens or any of the other “jungle gardens” that cater to the tourist trade.

Audubon stated, “Flamingos are rather rare and only during the summer in the Florida Keys and the western coast of Florida.” He was assured by various fishermen that they actually had found flamingo nests in some of the lagoons. He himself saw a number of flamingos in the vicinity of Key West and also on Indian Key, but never was able to shoot one. Flamingos exist in considerable numbers in the Bahamas and elsewhere in the West Indies, choosing salt ponds and lagoons that are secure from human intrusion. If a captive flock were to be introduced in the proper saline environment in southwest Florida it just might become established.

Harry Havell, a descendent of Audubon’s engraver, once showed me (R.T.P.) some proofs used by the colorists. These were not entire prints, but had been cut into irregular pieces, for what reason I cannot say. I particularly remember the flamingo on which Audubon had written in pencil, “more red here.” Possibly his memory exaggerated this point, for I always have thought he made this bird too deep in color. The famous captives at Hialeah lost their bright pink when first brought there, but regained it when they were fed a shrimp diet.