3

Lessons from Criminal Law

How Immigration Prosecutorial Discretion Compares to the Criminal System

The prosecutor has more control over life, liberty, and reputation than any other person in America. His discretion is tremendous. He can have citizens investigated and, if he is that kind of person, he can have this done to the tune of public statements and veiled or unveiled intimations. Or the prosecutor may choose a more subtle course and simply have a citizen’s friends interviewed. The prosecutor can order arrests, present cases to the grand jury in secret session, and on the basis of his one-sided presentation of the facts, can cause the citizen to be indicted and held for trial. He may dismiss the case before trial, in which case the defense never has a chance to be heard. Or he may go on with a public trial. If he obtains a conviction, the prosecutor can still make recommendations as to sentence, as to whether the prisoner should get probation or a suspended sentence, and after he is put away, as to whether he is a fit subject for parole. While the prosecutor at his best is one of the most beneficent forces in our society, when he acts from malice or other base motives, he is one of the worst.1

Prosecutors have long been viewed as powerful officials who exercise tremendous discretion over ordinary person’s life. While scholars have written extensively about the history, power, and abuse of criminal prosecutorial discretion,2 the literature has been less engaged with how prosecutorial discretion in the criminal system is related to such discretion in the immigration law system, a mostly civil system that possesses criminal-law-like features such as interrogation, arrest, detention, the filing of charges, and in some cases a hearing before an immigration judge with the government serving as the “prosecutor” and the noncitizen serving as the “defendant.” This chapter explains how immigration prosecutorial discretion relates to the criminal system by (1) describing the history of the American criminal prosecutor, (2) defining criminal prosecutorial discretion and identifying the discretion points at which prosecutorial discretion is exercised in the modern criminal system, and (3) examining how the immigration prosecutorial discretion compares to the criminal system.

The History of Prosecutions in America

The public understands modern criminal prosecution as something the government does, but this has not always been the case. When prosecutions were first developed in England and through the middle of the nineteenth century, they operated as a type of legal matter initiated by private parties as opposed to the government.3 Just as a person today can initiate a civil case, hundreds of years ago victims could initiate criminal prosecutions. Criminal prosecutions were also viewed as a way to limit the power of the Crown.4 This system was adopted by colonial America, giving complete control of the prosecution to the crime victim.5 As described by Professor Juan Cardenas, “Before the American Revolution, the crime victim was the key decisionmaker in the criminal justice system. Police departments and public prosecutors’ offices did not exist as they are known today. Law enforcement was the general responsibility of the private citizen.”6

Greater public interest concerns and the chaos involved in victims handling prosecutions challenged the value of private prosecutions.7 The first public prosecutor was an “attorney general” appointed in Virginia in 1643. In a process modeled after the English system, the attorney general was authorized to initiate prosecutions.8 Over time, the model of elected public prosecutors emerged, as did a federal prosecution system. The Judiciary Act of 1789 created the first federal Office of the Attorney General and provided for district attorneys, though without a clear configuration or hierarchy.9 The position of attorney general began as a part-time post filled by one person. The duty of the attorney general was “to prosecute and conduct all suits in the Supreme Court in which the United States shall be concerned, and to give his advice and opinion upon questions of law when required by the President of the United States, or when requested by the heads of any of the departments, touching any matters that may concern their departments.”10 Since 1870, the Department of Justice has housed more than ninety U.S. attorneys who serve as federal prosecutors. In addition, district attorneys in each state prosecute state crimes. In most states, there is one district attorney and several “assistant” district attorneys in each district. Private prosecutors still exist in a limited form, as the government allows a private attorney to perform a prosecutorial function in certain cases.11

By the early 1900s, American prosecutors became powerful figures in the criminal law structure.12 Even though prosecutors were elected and were more visible to the public, prosecutors were not always perceived as benevolent. The unresolved characterization of prosecutors was that they wielded too much power and without any oversight would be able to abuse their discretion or act inconsistently in cases bearing similarly relevant facts. Alongside the growth of prosecutorial power was growth in police power. Police worked side by side with public prosecutors and often exercised a great deal of discretion.

Beginning in the 1920s, “crime commissions” were developed to study the criminal justice system.13 President Herbert Hoover created one of the most popular crime commissions, the National Commission on Law and Observance and Enforcement (popularly known as the Wickersham Commission, named after the former Attorney General George W. Wickersham). The commission’s study was published in fourteen volumes and included topics like the causes of crime, police misconduct, and prosecution. The study identified abuses with police and prosecutorial power and discretion and made practical recommendations to resolve these problems.14 For example, the Wickersham Commission found that elected prosecuting attorneys failed to improve “checks” on the discretionary decisions of the prosecutor.15 Furthermore, it identified the plea bargaining stage as an “abuse” of the criminal process and recommended greater oversight at the state level by a “director of public prosecutions.”16 In 1931, the Wickersham Commission wrote, “In every way the prosecutor has more power over the administration of justice than the judges, with much less public appreciation of his power. We have been jealous of the power of the trial judge, but careless of the continual growth of the power of the prosecuting attorney.”17

Criminal Prosecutorial Discretion

Today, prosecutorial discretion is a main feature of the criminal justice system and is exercised by prosecutors in various ways. When a prosecutor declines to bring charges or chooses to file lesser charges, he or she is exercising prosecutorial discretion favorably. One of the most important stages is after an arrest, when the prosecutor decides whether to charge a person with committing a crime. This decision is so powerful because a charge may lead to detention, public humiliation, and/or a conviction. The authority for prosecutorial discretion in criminal law can be found in the U.S. Constitution and has further been affirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court,18 and by the U.S. Attorney’s Office.19 For example, in U.S. v. Armstrong, the U.S. Supreme Court held,

The Attorney General and United States Attorneys retain “broad discretion” to enforce the Nation’s criminal laws. Wayte v. United States, 470 U.S. 598, 607 (1985) (quoting United States v. Goodwin, 457 U.S. 368, 380, n. 11 (1982)). They have this latitude because they are designated by statute as the President’s delegates to help him discharge his constitutional responsibility to “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.” U.S. Const., Art. II, §3; see 28 U.S.C. §§516, 547. As a result, “[t]he presumption of regularity supports” their prosecutorial decisions and, “in the absence of clear evidence to the contrary, courts presume that they have properly discharged their official duties.” United States v. Chemical Foundation, Inc., 272 U.S. 1, 14-15 (1926). In the ordinary case, “so long as the prosecutor has probable cause to believe that the accused committed an offense defined by statute, the decision whether or not to prosecute, and what charge to file or bring before a grand jury, generally rests entirely in his discretion.” Bordenkircher v. Hayes, 434 U.S. 357, 364 (1978).20

The theory behind criminal prosecutorial discretion is tied to the availability of resources and the public interest. The economic reasons are articulated well by former Attorney General Robert H. Jackson before the Conference of United States Attorneys in 1940: “No prosecutor can even investigate all of the cases in which he receives complaints. If the Department of Justice were to make even a pretense of reaching every probable violation of federal law, ten times its present staff would be inadequate.”21 While some may believe that any person who violates a criminal law should be prosecuted, the growth of criminal statutes over the past century and the preservation of outdated laws mean that the federal government must target some crimes over others. Angela Davis describes how outdated laws such as fornication and adultery and minor infractions like gambling in the context of “placing small bets during a Saturday night poker game in a private home” may warrant a favorable exercise of criminal prosecutorial discretion.22 The growth in criminal statutes is staggering and sometimes referred to as “overcriminalization.” As described by one scholar and former attorney at the Justice Department:

Today, the fact of the matter is that if someone were to look hard enough, they’d likely discover that we’re all criminals, whether we know it or not, and regardless of whether we have any intent to violate the law. . . . Today, however, buried within the 51 titles of the United States Code and the far more voluminous Code of Federal Regulations, there are approximately 4,500 statutes and another 300,000 (or more) implementing regulations with potential criminal penalties for violations. There are so many criminal laws and regulations, in fact, that nobody really knows how many there are, with scores more being created every year. And that’s just federal offenses. Every new law gives prosecutors more power, and many of these laws, unfortunately, contribute to the overcriminalization problem.23

While prosecutorial discretion is not viewed as the only solution to the “overcriminalization problem,” it is an important tool used in the criminal justice system to place Saturday night poker players on the back burner. More ambitious solutions that have been proposed include revamping the criminal laws and modifying the sentencing guidelines.

The “public interest” basis for criminal prosecutorial discretion considers the impact of prosecution on the community and victim and factors such as the victim’s age and health. The relationship between the crime victim and the prosecutor is a complex one. Angela Davis advises that while prosecutors should support crime victims, their obligations are broader and may potentially conflict with the victims’ goals.24 Beyond the impact on a victim are factors that relate to the personal circumstances of the accused. For example, the U.S. Attorneys’ Manual identifies “extreme youth, advanced age [and] mental and physical impairment” of the accused as potential reasons to decline prosecution.25 Likewise, Attorney General Eric Holder noted recently that many of the “low-level” drug offenders placed into the criminal justice system are of a young age. The “public interest” prong of criminal prosecutorial discretion also considers the political reasons that influence prosecutorial decisions. For example, Senator David Vitter (R-LA) confessed to committing the crime of paying a prostitute to have sex with him. He was never arrested or charged, nor did he spend one day in jail.26 By exercising prosecutorial discretion to not arrest Senator Vitter, the federal government avoided embarrassment and what some would argue advanced the public interest so that he could carry out his job as a senator.

As introduced in the preceding paragraph, the government has published guidelines on prosecutorial discretion in the U.S. Attorneys’ Manual (USAM). The USAM is an internal guide of policy and procedures for U.S. attorneys, assistant attorneys, and district attorneys responsible for prosecuting violations of federal law. Within the chapter pertaining to the criminal division is a section on the principles of the prosecution function. These guidelines were first published in 1980 by Attorney General Benjamin R. Civiletti and remain the seminal memoranda.27 In determining whether prosecution should be declined because no substantial federal interest would be served by prosecution, the USAM advises attorneys to consider the seven following factors: (1) federal law enforcement priorities, (2) nature and seriousness of the offense, (3) deterrent effect of prosecution, (4) sufficiency of evidence to prove culpability, (5) prior criminal history, (6) willingness to cooperate with investigations or prosecutions of others, and (7) potential sentence and related consequences if convicted.28 The USAM notes that not every factor needs to be complied with for a federal prosecutor to decline prosecution.29 Many of these factors are personal and based on the facts of each individual case, such as the age of the victim and the history of the accused. The very first factor, federal enforcement priorities, rests more specifically on the economic reasons for targeting limited law enforcement resources on the most serious offenders or the government’s highest priorities. In discussing the nature and seriousness of an offense, the USAM notes that “[i]t is important that limited federal resources not be wasted in prosecuting inconsequential cases or cases in which the violation is only technical.”30 Illustrating this point, Davis comments on the discretion used by police each time someone commits a traffic violation.31 She argues that few people would be supportive of a law that required police officers to issue tickets to every person who committed a traffic violation.32 Davis also argues that the populace would assent that officers should preserve their limited resources for “more serious offenses” rather than traffic-related ones.33

Discretionary Points and Standards for Criminal Prosecutorial Discretion

Now that the legal authority for and theory of criminal prosecutorial discretion has been established, this section addresses at what point or points in the criminal process prosecutorial discretion can be exercised. There are many stages of the criminal process. Police play a significant role in the criminal process and carry significant discretion because they have the power to arrest, search, seize, and interrogate. The police officer may also play a role in recommending charges to the prosecutor or making a decision about whether to investigate alleged misconduct. Kenneth Culp Davis, emphasizing the central role of police in the justice process, estimated that about half of the discretionary decisions made by criminal justice agencies are made by police: “The police are among the most important policymakers of our entire society. And they make far more discretionary determinations in individual cases than any other class of administrators; I know of no close second.”34

Once an arrest has been made, most of the discretionary power shifts to the prosecutor. The Vera Institute for Justice has identified the following “discretion points” at which a prosecutor may exercise discretion:

• Initial screening—when a reviewing prosecutor decides whether to accept a case for prosecution and, in some instances, how to charge the offense

• Pretrial release or bail procedure—whether a defendant is held in detention while the case is pending and whether a defendant is offered or awarded bail

• Dismissal—whether a case or charge is dismissed at any point after initial screening by a prosecutor or a judge

• Charge reduction—whether the seriousness or the number of charges are reduced at any point after initial screening

• Guilty plea—whether a defendant pleads guilty

• Sentencing—whether a prosecutor’s decisions affect the length or nature of a convicted person’s penalty35

This section describes some of the stages outlined above: charging, grand jury, plea bargains, and sentencing. Following an arrest, the prosecutor decides whether to file charges and what kind of charges to file. The prosecutor must decide whether to decline prosecution in a case where he or she has evidence that amounts to probable cause that a crime has been committed. If a prosecutor decides not to bring charges, the person is free to go.36 Several scholars have identified the charging stage as the most powerful: “The decision to charge an individual with a crime is the most important function exercised by a prosecutor. No government official can affect a greater influence over a citizen than the prosecutor who charges that citizen with a crime. In many cases, the prosecutor determines the fate of those accused at least in those cases where the evidence or statutory sentencing structure renders the ultimate outcome of the prosecution largely a foregone conclusion.”37 Even in an instance where the criminal charge is filed but no conviction results, the impact this filing can have on the accused is life changing and results in “potential pretrial incarceration, loss of employment, embarrassment and loss of reputation, the financial cost of a criminal defense, and the emotional stress and anxiety incident to awaiting a final disposition of the charges,”38 in addition to potential contact with immigration authorities. A decision to charge can also result in prolonged incarceration because many convictions carry “mandatory minimum” sentences.

The USAM guidelines advise government attorneys to give this calculation careful thought. The American Bar Association’s Criminal Justice Section has also issued guidelines focused on charging decisions:

(b) The prosecutor is not obliged to present all charges which the evidence might support. The prosecutor may in some circumstances and for good cause consistent with the public interest decline to prosecute, notwithstanding that sufficient evidence may exist which would support a conviction. Illustrative of the factors which the prosecutor may properly consider in exercising his or her discretion are:

(i) the prosecutor’s reasonable doubt that the accused is in fact guilty;

(ii) the extent of the harm caused by the offense;

(iii) the disproportion of the authorized punishment in relation to the particular offense or the offender;

(iv) possible improper motives of a complainant;

(v) reluctance of the victim to testify;

(vi) cooperation of the accused in the apprehension or conviction of others; and

(vii) availability and likelihood of prosecution by another jurisdiction.39

While the standards published by the USAM and ABA are clear about the responsibility prosecutors have in deciding whether and what kind of charges to bring against the accused, critics have argued that the USAM is not a legally binding document and that as a practical matter “there is generally not a lot of soul searching about the decision to prosecute.”40 As illustrated by criminal law scholar Abbe Smith, “Unfortunately, I have witnessed many examples of this behavior, too many to count. In one memorable case, there was compelling evidence that the perpetrator of a serious physical assault was someone other than the defendant. The case carried a mandatory minimum prison sentence of five years. After discussions with the prosecutor—and disclosure of more defense evidence than is usually my practice—the prosecutor conceded that he did not know who committed the crime. However, instead of declining to prosecute, he shrugged and said ‘Let’s just let the jury decide.’ ”41

Another relevant point in the criminal process is the grand jury stage. Importantly, federal courts must utilize the grand jury process for felony charges. This means that the citizen-jurors together must decide whether there is probable cause that a defendant committed a felony offense.42 While it may appear that the grand jury serves as an important “check” to the arresting police officer and prosecutor in determining whether a formal charge should be made, some scholars argue that it is the prosecutor who actually controls the grand jury process.43 As described by Professor Kevin Washburn, “Despite the widespread belief that the grand jury’s role is to serve as a check on the prosecutor, the grand jury is widely criticized for failing to live up to this role. The criticism is reflected in a cliché common among academics and practitioners that a skillful prosecutor could convince a grand jury to indict ‘a ham sandwich.’ ”44

A further point in the criminal process is plea bargaining. Prosecutors wield a great amount of power during the plea bargaining phase,45 which Angela Davis describes as a negotiation between the prosecutor and the defense attorney in which the former may offer to dismiss a charge in exchange for a defendant’s plea to another charge.46 Plea bargaining allows the prosecutor to succeed in cases without the expense of trial and further provides the prosecutor with an opportunity to prevail in some of the cases that he or she may have lost had they gone to trial.47 Davis offers the example of someone who is guilty of breaking into a home and stealing several items—in this case, a prosecutor might consider the charge of first degree burglary, second degree burglary, or destruction of property and then offer second degree burglary in exchange for the prosecutor’s agreement to dismiss all other charges.48 It is striking that 97 percent of federal convictions and 94 percent of state convictions are the result of guilty pleas as opposed to trials.49 Justice Anthony Kennedy remarked, “The reality is that plea bargains have become so central to the administration of the criminal justice system that defense counsel have responsibilities . . . that must be met to render the adequate assistance of counsel that the Sixth Amendment requires.”50 The plea bargaining stage of the criminal process is so critical that the Supreme Court has extended the Sixth Amendment right to counsel to the plea bargaining process.51

A final point in the criminal system worthy of discussion is sentencing and imprisonment. America has the largest incarceration system in the world, with a nationwide cost of eighty billion dollars in 2010 alone.52 In many instances, prosecutors have the power to determine whether a person is incarcerated and for how long because of the increased prevalence of “mandatory minimum” sentencing laws. Mandatory minimum sentencing laws impose a specified time frame for imprisoning a defendant based on his or her offense. In this way, the charge and the plea are directly tied to the time a defendant spends incarcerated. As confirmed by Angela Davis, “Because almost all criminal defendants ultimately plead guilty, the charging and plea bargaining decision of prosecutors essentially predetermine the outcome in criminal cases with mandatory minimums.”53 In a speech to the American Bar Association House of Delegates in August 2013, Attorney General Holder rolled out a plan for reforming the criminal justice system and underscored the special role of prosecutorial discretion.54 Specifically, Holder said that he would instruct federal prosecutors to exercise their prosecutorial discretion by charging defendants in certain low-level drug cases in such a way that would avoid a mandatory minimum prison sentence.55 As described by Holder, “federal prosecutors cannot—and should not—bring every case or charge every defendant who stands accused of violating federal law. Some issues are best handled at the state or local level.”56

Criminal Prosecutorial Discretion: Theory versus Practice

Having described the procedural points at which a prosecutor may exercise discretion and the various legal authorities and documents that have been produced in support of criminal prosecutorial discretion, one remaining question is whether the theory of criminal prosecutorial discretion is properly tied to the practice of how it is exercised. A study by the Vera Institute of Justice provides an “on the ground” view of the factors that drive prosecutors to exercise discretion. Titled “The Anatomy of Discretion,” the Vera study is the culmination of a two-year research project using data from two large county prosecutors’ offices and authored by Bruce Frederick and Don Stemen.57 The Vera study demonstrates the following findings about the factors that influence prosecutorial discretion decisions:

• Strength of the evidence was the primary consideration at screening and continued to influence decisions throughout the processing of a case.

• Seriousness of the offense influenced decisions throughout the processing of a case.

• Victims’ characteristics, circumstances, wishes, and willingness to testify affected prosecutors’ evaluations of both the strength of the evidence and the merits of the case.

• In deciding whether or how a case should proceed, prosecutors were guided by an overarching philosophy of doing justice—or “the right thing.” Most participants described justice as a balance between the community’s public safety concerns and the imperative to treat defendants fairly. In considering that balance, survey respondents overwhelmingly considered fair treatment to be more important than public protection.

• In addition to considering legal factors, prosecutors evaluated defendants’ personal characteristics and circumstances to judge whether the potential consequences of case dispositions would be fair.58

Though the findings by Vera suggest that prosecutors are driven by the “public interest” broadly speaking, the study goes on to identify less grand factors that influence prosecutorial decision making. As described by Frederick and Stemen: “While prosecutorial discretion is generally seen as very broad and unconstrained, prosecutors often rely on a small number of salient case characteristics, and their decision making is further constrained by several contextual factors. These contextual constraints—rules, resources, and relationships—sometimes trump evaluations of the strength of the evidence, the seriousness of the offense, and the defendant’s criminal history. Chief prosecutors and criminal justice policy makers should be alert to the potential for contextual factors to influence and possibly distort the exercise of prosecutorial discretion.”59

A 1987 study by Celesta Albonetti examined the factors influencing a government attorney’s decision to prosecute.60 Relying on a data set of 6,014 felony cases generated by the Superior Court of Washington, D.C., Albonetti concludes that a government attorney’s decision to prosecute is driven by a “generalized preference for avoiding uncertainty, many of which may be related to the public interest.”61 Albonetti found that the existence of exculpatory evidence, the presence of corroborative or physical evidence, the number of witnesses, the presence of the defendant at the scene of the crime, stranger (as opposed to intimate or acquaintance) relationships, the innocence and credibility of the witness, and the use of a weapon were statistically significant to the probability of prosecution.62

Professional advancement also influences prosecutorial decision making. As described by Albonetti: “There is little ambiguity within the prosecutor’s office regarding the criteria of successful movement within the profession and the hierarchically arranged office. Prosecutorial success, which is defined in terms of achieving a favorable ratio of convictions to acquittals, is crucial to a prosecutor’s prestige, upward mobility within the office, and entrance into the political arena.”63 Similarly, Abbe Smith argues that prosecutors are under pressure to “win” because it affects both external benefits and internal ones, like salary and promotion.64 It is difficult to understand how a prosecutor can be expected to refrain from filing charges against an individual who is accused of committing a crime when his or her salary is driven by the number of convictions he or she secures. On the other hand, the ABA’s Criminal Justice Section advises, “In making the decision to prosecute, the prosecutor should give no weight to the personal or political advantages or disadvantages which might be involved or to a desire to enhance his or her record of convictions.”65

Beyond the scope of this book are the racial disparities that exist in the criminal justice system at the time of charging and throughout the criminal process. Many scholars have described these disparities in rich detail.66 Attorney General Holder also addressed racial disparities in sentencing when he remarked, “We also must confront the reality that, once they’re in that system, people of color often face harsher punishments than their peers.” He said, “This isn’t just unacceptable—it is shameful.”67

How Immigration Prosecutorial Discretion Compares to the Criminal System

As in the criminal justice system, prosecutorial discretion is a main feature of the immigration system and may be exercised in a variety of ways. While an immigration officer is not a prosecutor in the technical sense, he or she has the same authority to decline to bring charges or choose which charges to bring against a noncitizen. The legal authority for immigration prosecutorial discretion has been affirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court.68 For example, in Arizona v. United States, the Supreme Court noted: “A principal feature of the removal system is the broad discretion exercised by immigration officials. Federal officials, as an initial matter, must decide whether it makes sense to pursue removal at all.”69

The authority for immigration prosecutorial discretion has also been confirmed by the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS).70 While INS memoranda have been well summarized in chapter 2, they are revisited in this chapter for the single purpose of examining how they demonstrate that INS guidelines resemble criminal prosecutorial discretion policies. For example, the 1976 legal opinion by Sam Bernsen noted the following analogy between criminal law and administrative law when discussing prosecutorial discretion: “Prosecutorial discretion refers to the power of a law enforcement official to decide whether or not to commence or proceed with action against a possible law violator. This power is not restricted to those termed prosecutors, but is also exercised by others with law enforcement functions such as police and officials of various administrative agencies. The power extends to both civil and criminal cases.”71 Similarly, former general counsel for the INS Bo Cooper drafted a memorandum on prosecutorial discretion noting that “[t]he idea that prosecutor is vested with broad discretion in deciding when to prosecute, and when not to prosecute, is firmly entrenched in American law.”72

The immigration agency has relied heavily on the guidelines established for criminal prosecutorial discretion to formulate its thinking on immigration prosecutorial discretion.73 For example, the INS memorandum from Doris Meissner on prosecutorial discretion relies on the U.S. Department of Justice’s USAM’s Principles of Federal Prosecution.74 At that time, INS was part of the Department of Justice. As explained earlier, the Principles of Federal Prosecution governing the conduct of U.S. attorneys use the concept of a “substantial Federal interest.”75 Based on this principle, the Meissner Memo states that “[a]s a general matter, INS officers may decline to prosecute a legally sufficient immigration case if the Federal immigration enforcement interest that would be served by prosecution is not substantial.”76 Referencing the USAM, the Meissner Memo lists some beneficial aspects of such principles: “Such principles provide convenient reference points for the process of making prosecutorial decisions; facilitate the task of training new officers in the discharge of their duties; contribute to more effective management of the Government’s limited prosecutorial resources by promoting greater consistency among the prosecutorial activities of different offices and between their activities and the INS’ law enforcement priorities; make possible better coordination of investigative and prosecutorial activity by enhancing the understanding between the investigative and prosecutorial components; and inform the public of the careful process by which prosecutorial decisions are made.”77 As in the criminal system, the theory behind immigration prosecutorial discretion is tied to economic and humanitarian reasons. The guidelines identified in chapter 2 and the more recent documents outlined in chapter 5 all premise immigration prosecutorial discretion on resources and compassion.78 As an example, one memorandum published by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement in June 2011 lists both adverse factors such as the seriousness of the crime, the person’s criminal history, and whether a person is a repeat offender, as well as humanitarian factors like a close family relationship, presence in the United States since childhood, and a serious medical condition, which the officer should consider in determining whether or not prosecutorial discretion should be exercised favorably.

The concept of “overcriminalization” also exists in the immigration system. The Immigration and Nationality Act includes a robust list of infractions that constitute violations of immigration law, and subject a person to deportation. These offenses can be captured in roughly five different categories: health, moral-related, immigration control, crime-related, and national security-related. The spectrum of conduct leading to deportation is broad and striking and includes failure to file a change of address card within ten days of moving,79 crimes involving “moral turpitude,”80 being present in the United States without admission,81 and the accrual of more than 180 days of “unlawful presence.”82

As with criminal law, there are several discretionary points in the immigration enforcement process. These discretionary points include:

• Interrogation

• Apprehension or arrest

• Civil detention

• Charging and charge reduction

• Removal from the United States

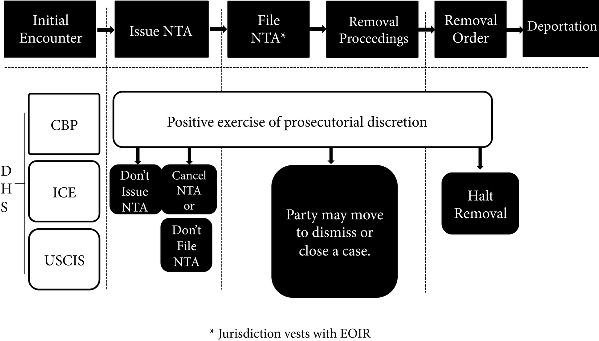

Many of the discretionary points resemble similar points in the criminal law system but have a different legal standard because the immigration system is considered “civil.” Immigration officers enjoy broad authority to interrogate and arrest noncitizens for suspected immigration violations.83 Moreover, there are several different kinds of officers who have authority to prepare, issue, and file charges against a noncitizen who is alleged to be in violation of the immigration laws.84 In this way, the act of bringing charges against a noncitizen is not limited to the “prosecutor” but instead can be performed by a variety of officers at different ranks and units within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). Specifically, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) all have authority to issue or file a Notice to Appear (NTA).85 The NTA is the immigration agency’s charging document that informs the noncitizen about his or her status and the charges from the government’s point of view.86 Within the charging process officers may take (or refrain from taking) a wide variety of actions in their discretion. Many of the recent memoranda from DHS name these discretionary points as a valid exercise of prosecutorial discretion. To illustrate, the Morton Memo states that prosecutorial discretion applies to “deciding to issue, reissue, serve, file, or cancel a Notice to Appear (NTA).”87

To demonstrate how discretion might be exercised during the charging process, an ICE officer can arrest a young woman because he believes she is present in the United States without permission but, upon discovering that she is the mother of a U.S. citizen, choose not to issue an NTA. Even after an NTA issued, this same officer or another employee in DHS can choose not to file the NTA with an immigration court as a matter of prosecutorial discretion. Even after the NTA is filed with the immigration court, an ICE trial attorney can move the immigration court to dismiss removal proceedings by removing the NTA and case from the court’s docket.

Fig. 3.1. Prosecutorial discretion in the Notice to Appear (NTA) process.88

Data published by the Office of Immigration Statistics within DHS reveal that DHS issued 233,958 NTAs in 2012, and that 140,707 of these NTAs were issued by ICE. Notably, 40,049 of these NTAs were issued by USCIS; 31,506 were issued by the Border Patrol within CBP; and 21,696 were issued by the Office of Field Operations, a unit within CBP.89 Likewise, data obtained through the Freedom of Information Act indicate that CBP issued 64,000 NTAs during fiscal years 2011 and 2012 to nationals from over forty-five countries.90 Likewise, data from USCIS reveal that more than 97,000 NTAs were issued during fiscal years 2011 and 2012.91 While these data sets lack information about whether the NTAs issued were actually filed with the immigration court or instead cancelled as a matter of prosecutorial discretion, they do uncover significant evidence about the breadth of players at DHS who use their discretionary authority to issue charging documents to noncitizens. During the charging process, ICE attorneys may review an NTA before it is filed with the immigration court or upon review decide that it is not prudent to file an NTA, but this is not a required practice or rule in immigration law.92

The charging process is complex not only because a range of players can and do exercise discretion to issue, cancel, or file charges against a noncitizen, but also because some noncitizens may actually benefit from an NTA and removal proceedings. To understand this phenomenon, it should be explained that the Immigration and Nationality Act stipulates that categories of people such as those “arriving” at a border without documents or false documents, non–green card holders who are already inside the United States but who have been convicted of an aggravated felony, and those inside the United States who entered without authorization after receiving an order of removal on their record may be deported (removed) by an immigration officer without an NTA or formal removal proceeding before an immigration judge.93 If an NTA is filed, the person therefore benefits from having a formal hearing at which he or she may challenge removability or apply for relief before an immigration judge. Another class who may benefit from an NTA are those who are eligible for reprieve from removal before the immigration judge through a form of relief known as cancellation of removal.94 Whereas DHS and the Department of Justice both enjoy jurisdiction to grant various forms of relief from removal such as a green card, waivers of inadmissibility, and asylum, cancellation of removal is a special remedy that is available only in removal proceedings. Take the example of Maria, an undocumented mother of three young U.S. citizen children, one of whom suffers from autism. Maria has resided in the United States for twenty years, acted as the primary caregiver for her children, worked at a private school teaching Spanish, and received no negative mark on her record beyond the charge of being present without admission. Maria might qualify for cancellation of removal but cannot apply for this relief unless she is before an immigration judge as a result of having been placed into removal proceedings.

The immigration system does not have the same kind of plea bargaining stage as exists in the criminal system, but there is a type of plea bargaining called “voluntary departure.”95 Voluntary departure is a term of art that enables DHS to permit a noncitizen to depart the United States at his or her own expense in lieu of a removal order.96 Another form of plea bargaining is a “stipulated order of removal,”97 which means that the noncitizen “agrees” to a formal order of removal, makes no application for relief, and waives his or her right to a hearing before the immigration judge. While the stipulated order of removal program offers more efficiency to the government by avoiding a separate immigration court proceeding and related government resources, scholars have questioned the program’s disproportionate impact on individuals who are incarcerated and without counsel.98

Notably, there is no “sentencing” stage in the immigration system. Thus, unlike criminal prosecutors, DHS officials do not exercise prosecutorial discretion during a separate sentencing phase. Moreover, if a noncitizen is “convicted” of a violation of immigration law and ineligible for any kind of relief such as cancellation of removal, asylum, or a green card, then he or she is ordered deported or detained until the appropriate travel documents are secured to deport him or her. Throughout the immigration process, a noncitizen may be detained by DHS.99 There is no “statute of limitations” on immigration charges, nor is there a limit on how long a noncitizen may be detained pending a charge of removal, during the removal process, or even after a removal order is granted.100 Thus, DHS wields enormous prosecutorial power to decide whether a noncitizen should be detained in a prison, placed on “alternatives” to detention, released on a bond, or freed on his or her own recognizance. Many of the guidance documents published by the immigration agency recognize the role prosecutorial discretion plays during the detention process.101 One more recent prosecutorial discretion memo from ICE formalizes a policy that supports keeping parents who are targeted by ICE out of detention.102 According to one agency official, “[The memo] clarifies that ICE officers and agents may, on a case-by-case basis, utilize alternatives to detention for these individuals particularly when the detention of a non-criminal alien would result in a child being left without an appropriate parental caregiver.”103 While the statute, regulations, and agency all support prosecutorial discretion during the detention process, Congress has identified categories of people who “shall” be detained during the enforcement process. For example, noncitizens who have been convicted of an aggravated felony “shall be detained” by the immigration agency pending removal.104 Meanwhile, the U.S. Supreme Court and several federal courts have concluded that prolonged detention without a bond hearing violates due process.105 Moreover, DHS retains discretion even when statutes use the word “shall.”

As this section shows, the points at which prosecutorial discretion may be exercised during the immigration enforcement process bear many of the same features as in criminal law. Even where the stages themselves are labeled differently, such as plea bargaining in criminal law and voluntary departure in immigration law, the concepts are quite similar. In fact, immigration advocates drew a sharp parallel between the mandatory minimum system in criminal law and the mandatory detention provisions of the immigration statute following the August 2013 announcement by Attorney General Holder of reforms to the criminal justice process.106 As described by one immigration lawyer: “Our current immigration deportation laws similarly impose mandatory minimum sentences for thousands of immigrants convicted of ‘aggravated felonies’—a category so broad as to encompass crimes that are neither aggravated nor felonies. These mandatory minimum sentences under immigration law, however, do not result in jail sentences, but rather permanent exile from the U.S., for even long term lawful permanent residents and refugees, without any consideration of the individual circumstances of their cases.”107 The lawyer was thus analogizing the harsh consequences in the criminal system of mandatory minimums to the mandatory banishment that occurs in the immigration system and arguing for the necessity of discretion.

While there are similarities between the function of prosecutorial discretion in the criminal justice system and that in the immigration system, the following section elucidates two sharp differences. First, immigration is a civil system and is driven by a set of rules and procedures that are quite different from those in the criminal system. At the early stages, DHS employees function as police officers and prosecutors in many cases as they hold the power to interrogate, arrest, and bring charges against a noncitizen. Even without charges, a noncitizen can be held in custody for forty-eight hours or longer “in the event of an emergency or other extraordinary circumstance in which case a determination will be made within an additional reasonable period of time.”108 The practical consequence is that a noncitizen can be arrested and held in a prison by ICE without any charges so long as the agency has identified an “extraordinary circumstance” under which to hold him or her. Similarly, neither the regulations nor the Immigration and Nationality Act contain a time frame for serving an arrested noncitizen with charging papers or filing such papers with the immigration court. In many cases, immigration defendants will not see a judge until the Notice to Appear is filed with the court and the initial hearing is scheduled. Furthermore, unlike the criminal system, the civil immigration system does not include a grand jury to secure felony charges. Finally, people who are charged with violations of immigration law are not guaranteed a right to court-appointed counsel.109 As illustrated sharply in a study analyzing immigration counsel in New York City, “A noncitizen arrested for jumping a subway turnstile of course has a constitutional right to have counsel appointed to her in the criminal proceedings she will face, notwithstanding the fact that it is unlikely she will spend more than a day in jail. If, however, the resulting conviction triggers removal proceedings, where that same noncitizen can face months of detention and permanent exile from her family, her home, and her livelihood, she is all too often forced to navigate the labyrinthine world of immigration law on her own, without the aid of counsel.”110 The practical effect is that many noncitizens or unlawfully held U.S. citizens navigate the removal process and related court hearings without counsel.111 Finally, a noncitizen who has not yet been admitted into the United States bears the burden of proving that he or she is “clearly and beyond doubt” entitled to be admitted.112 Likewise, the government need only prove deportability only by “clear and convincing evidence” for a person who has been deemed “admitted” into the United States and charged with deportability.113 Insofar as prosecutorial discretion in immigration law comes with far fewer safeguards than are present in the criminal law context, oversight and accountability of prosecutorial discretion making in immigration matters are vital.

The influences and incentives that drive immigration prosecutorial discretion are also somewhat distinct from those that typically influence criminal prosecutorial discretion. Notably, immigration-related violations do not typically involve a “victim,” so factors such as the credibility of the victim and the desire by the victim to move forward in a case do not play a major role (if any) in immigration cases. Immigration prosecutors have traditionally lacked incentives to forgo prosecution or remove an existing immigration case from the removal docket as a matter of prosecutorial discretion,114 but the winds may be blowing in a different direction with the advent of guidance documents and more public fanfare by DHS about the importance of exercise prosecutorial discretion in appropriate cases.