4

Deferred Action

Examining the Jewel (or a Precious Form) of Prosecutorial Discretion

In 2001, my Nanay (Mom in Tagalog) made the hardest decision of her life—leaving my two siblings and me behind in the Philippines in order to seek a better life and future for our family. While we came a few months later, my parents had to work long hours just to put food on the table and provide for our family’s needs. Only after I’d grown up did I realize they worked so hard not only to take care of our family but because they had something to prove to themselves, to society, and to their children. They worked tirelessly to prove that they made the right choice for our family to move to the U.S. It was in the 10th grade that I found out about my undocumented status. I really didn’t know what it meant and what to feel at that moment. When I started to apply for college, I realized my life was limited by not having a social security number but I was determined to succeed no matter what. In 2011, I graduated from University of California–Irvine with a Bachelors of Art in Political Science. . . . My dream is to draw on the law and public policy as a tool to organize my community and I hope to earn a joint degree in Law and a master’s in Urban Planning in the near future. Someday, I hope to pursue a PhD to teach Asian American Studies in a University and empower my community.1

This quote comes from Anthony, an undocumented Filipino living in the United States who qualified for a special form of deferred action called Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA).2 This chapter educates the reader about deferred action, one of the most precious forms of prosecutorial discretion. The chapter is broken into three parts: (1) general history of deferred action in immigration law, (2) the use of deferred action to protect victims of domestic violence, sexual assault, and other crimes, and (3) an analysis of deferred action data retrieved from INS and DHS. As recounted earlier, deferred action is one of many forms of prosecutorial discretion.3

General Background about Deferred Action

Deferred action is a form of prosecutorial discretion that has been applied to both individuals and groups meeting qualifying criteria. In theory, any person who is in the United States without authorization may apply for deferred action before any component of DHS. The outcome when someone applies for deferred action cases is perhaps obvious. An application may be granted, denied, or unresolved.4 What is less obvious is the lack of transparency behind grants of deferred action. Historically, the agency took action on a deferred action request but applicants were not necessarily informed about the outcome. Part of the transparency problem is that deferred action—like most forms of prosecutorial discretion—has operated without a formal application form or a fee, or any process for appealing a denial. Once a person is granted deferred action, he or she is eligible to apply for work authorization and remain in the United States in legal limbo. The regulations that govern immigration law contain a specific subsection for individuals applying for work authorization on the basis of deferred action.5 Yet if a person is denied deferred action, there is no mechanism for review by DHS or the immigration court.6 Despite the fact that grave consequences attach when an agency fails to grant a person deferred action status, nonattorney DHS employees can make decisions about deferred action.7 Nevertheless, deferred action is an important form of protection for undocumented persons seeking a way to live and work with dignity in the United States without the fear of deportation.

As described in chapter 2, INS first used the term “deferred action” in an internal memorandum known as an “Operations Instruction.” The agency had dozens of Operations Instructions to guide INS officers on a variety of issues, but the Operations Instructions themselves lacked the force of law. Among the list of “instructions” was a specific one pertaining to the use of deferred action.8 While the instruction was eventually removed from the public policy roster at INS, deferred action remained as internal guidance in the Meissner Memo issued in 2000. The Meissner Memo (named after former INS Commissioner Doris Meissner) read: “The ‘favorable exercise of prosecutorial discretion’ means a discretionary decision not to assert the full scope of the INS’ enforcement authority as permitted under the law. Such decisions will take different forms, depending on the status of a particular matter, but include decisions such as not issuing an NTA . . . not detaining an alien placed in proceedings . . . and approving deferred action.”9

The agency continued to recognize deferred action after INS was abolished and DHS was created in 2003. In 2005, Congress passed legislation containing specific language mentioning deferred action. This legislation described the necessary forms of evidence required to prove lawful status in the United States for a person seeking a federally recognized state driver’s license or identification card, and stated that someone with “deferred action” could be granted such a license.10 Likewise, DHS published several policy documents identifying “deferred action” as a form of prosecutorial discretion to use in compelling cases. For example, a memorandum issued by former ICE head John Morton identifies “granting deferred action” as an option for DHS to consider in deciding immigration cases.11 Likewise, USCIS contemplated the use of deferred action in a draft memorandum prepared for the director in the midst of a congressional stalemate over immigration reform. The draft memo contemplated that USCIS could increase its use of deferred action and possibly require a separate fee or appropriation. Deferred action has also been identified as a remedy to keep immigrants who are the spouses, parents, and children of military members together.12

Deferred action programs can also be created for special groups of people. At least three public deferred action programs to benefit classes of individuals have been unleashed in the past decade. On November 25, 2005, USCIS announced certain foreign students and eligible dependents impacted by Hurricane Katrina would be granted deferred action. The USCIS press release stated the following: “A grant of deferred action in this context means that, during the period that the grant of deferred action remains in effect, DHS will not seek the removal of the foreign academic student or his or her qualified dependents based upon the fact that the failure to maintain status is directly due to Hurricane Katrina. Deferred action requests are decided on a case-by-case basis.”13 On June 9, 2009, former DHS Secretary Janet Napolitano granted deferred action to certain widows and widowers of U.S. citizens (and their minor children) residing inside the United States.14 The most well-known deferred action program to benefit a specific class of persons came just before the 2012 presidential election. On June 15, 2012, the Department of Homeland Security issued a memorandum in tandem with an announcement from the White House that allows certain young people living in the United States without legal status to receive prosecutorial discretion in the form of “deferred action.”15 Formally known as Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, the program allows individuals to apply affirmatively for deferred action.16 DACA is a form of deferred action permitting mostly students inside the United States who entered as children to apply for deferred action. The DACA program extends to individuals currently in school, those who have graduated or obtained the equivalent of a high school diploma, and certain honorably discharged veterans of the U.S. military. DACA-eligible individuals can apply as long as they are in good standing and can produce the necessary documentation required by USCIS. DHS used traditional humanitarian factors to outline the parameters for the DACA program, such as tender age and longtime residence in the United States. The program was intended to address a humanitarian crisis that formed after Congress entered a stalemate over a legislative solution to protect young people pursuing higher education and those in the U.S. military from deportation by creating a legal channel that would have allowed them to remain in the United States with a formal legal status and the opportunity to eventually apply for a green card. The politics of this congressional demise is explained in more detail in chapter 5.

Prosecutorial Discretion for Victims of Crime and Abuse

Hernandez, who is originally from Mexico, said she lived with her abuser in the United States for ten years and was married for five. She said she never knew her husband was a citizen until the threats to report her to ICE became more frequent. He would say to her, she said, that ICE would deport her but they wouldn’t deport him. Hernandez’s two children are also American citizens, by birth, which means Hernandez could be separated from them, if deported. Her fear of being deported to Mexico was overwhelming, she said. “Mucho terror” (so much terror), she said, explaining her panic. Except for work, Hernandez said, she was isolated. She had three jobs to support her husband and her two children—a daughter, who is now 9 years old and a son, 21. “I felt very controlled,” she said, speaking through a translator. “I was a slave to work. I had to pay to maintain him and the kids and he would just take the checks from me. It was a very difficult situation, but it was normal for me. I didn’t know how to leave,” she said. Hernandez reported her husband to the police approximately ten times, she said, but each time the abuse got progressively worse. . . . “My biggest fear was being deported.” But Hernandez said she got the courage to work through her fear because silence has always been her worse enemy. . . . “Sometimes I ask myself where I would be if I didn’t have that visa. It’s difficult to think about that. I’m very fortunate,” she said. “My life has changed completely.”17

This woman lived in fear in the United States until she was granted lawful status as a holder of a U visa, a status she gained by reporting abuse to law enforcement and assisting in the prosecution of her abuser. At one stage of the process, she was the beneficiary of prosecutorial discretion—rather than deporting her for being unlawfully present, U.S. government officials chose to refrain from enforcing the law against her and instead pursue her abuser. The use of prosecutorial discretion to protect victims of domestic violence, human trafficking, and other crimes enjoys a rich history. Formal protections by Congress highlight the unique barriers that noncitizens face when living in an abusive relationship with a spouse, partner, or trafficker. Common forms of prosecutorial discretion used by the agency to protect such victims include deferred action, parole, stays of removal, and dismissal or closure of a case that has already been docketed for removal.18 While this chapter focuses largely on deferred action, I tuck in a description about general remedies available for victims.

As a first step to protecting immigrant victims, Congress in 1994 passed the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), a portion of which was codified in the INA.19 If an applicant for this kind of petition, commonly called a “VAWA Self-Petition,” is approved for VAWA status before a visa is immediately available, he or she is given “deferred action” status.20 The VAWA Self-Petition can protect (1) a spouse who is abused by a citizen or lawful permanent resident spouse, (2) children who are abused by a citizen or lawful permanent resident parent, and (3) parents who are abused by their adult citizen children.21 While a person in a relationship with a qualifying U.S. citizen or green card holder might ordinarily rely upon his or her spouse, parent, or child to “sponsor” the person for a visa under the family immigration system, VAWA allows the victim to petition on his or her own behalf without having to rely on the abuser.

The significant role of deferred action in the VAWA Self-Petition context evolved through a series of memoranda published by INS.22 In one memorandum, dated May 6, 1997, INS Acting Associate Commissioner Paul Virtue outlined the impact of the 1996 laws on a victim’s ability to obtain protection and employment by highlighting deferred action as the preferred remedy for appropriate cases.23 The memo instructed one USCIS unit, the Vermont Service Center (VSC), to place approved VAWA self-petitioners in deferred action status whenever possible so that immigrant victims could have the opportunity to work. Specifically, the Virtue Memo states, “[F]or many individuals, the ability to work is necessary in order to save the funds necessary to pay for the adjustment application and the penalty fee. As it has already been determined that these aliens face extreme hardship if returned to the home country and as removal of battered aliens is not an INS priority, the exercise of discretion to place these cases in deferred action status will almost always be appropriate.”24 On December 22, 1998, INS Acting Associate Commissioner for Programs Michael Cronin issued a more in-depth memorandum declaring the VSC responsible for deferred action determinations for all self-petitioners, their derivative children, and the children of abusive U.S. citizens and lawful permanent residents regardless of when and where their petitions were approved.25 The Cronin Memo set time frames for the duration of deferred action status in individual cases. Data from USCIS through April 2003 indicate that 30 of the 499 deferred action cases processed listed VAWA as a reason for why deferred action was granted. The USCIS references the May 6, 1997, Virtue Memo in evaluating whether a victim would suffer “extreme hardship” upon deportation.26 In one case that was granted, the paperwork from USCIS indicated “subject believes that if she returns to Mexico her husband will follow her and attempt to kill her.”27 VAWA was reauthorized by Congress in 2000, 2005, and March 2013.28 Between 1997 and 2011, 98,192 VAWA petitions were filed with USCIS, of which 75 percent were approved.29 One can predict that a good number of individuals approved for VAWA received “deferred action” as part of the process.

In addition to the VAWA Self-Petition, Congress later created the U and T visas to protect victims of crimes and human trafficking.30 These visas were created by Congress in 2000 as part of the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act (VTVPA), which implemented several different protections for immigrant victims.31 The U visa is intended to protect victims of crime, like the Hernandez.32 Specifically, the U Visa is available to victims of a qualifying crime who suffer from substantial physical or mental abuse, have information about the criminal activity, and are being or are likely to be helpful to the investigation and/or prosecution of that qualifying criminal activity.33 The INA caps the U visa category at ten thousand visas per year.34 In contrast, the T visa extends to victims who have suffered severe forms of trafficking. To receive a T visa, victims must be physically present in the United States and meet specific requirements, like showing they have been a victim of trafficking as defined under the law and would suffer extreme hardship involving severe and unusual harm if removed from the United States.35 The T visa category is capped at five thousand per year.36 Although Congress created the U and T visa categories in 2000, INS and later DHS took several years to publish the agency regulations necessary to issue the visas. In the absence of regulations, the agency relied on prosecutorial discretion as a Band-Aid solution for qualifying victims. On August 30, 2001, Michael Cronin circulated a memo outlining interim procedures to help individuals who would otherwise qualify for a U or T visa.37 The memo emphasized that these victims “should not be removed from the United States until they have had the opportunity to avail themselves of the [U and T visa]” and further advised “that it is better to err on the side of caution than to remove a possible victim to a country where he or she may be harmed by the trafficker or abuser, or by their associates.”38 The Cronin Memo revealed the agency’s support for a wider range of prosecutorial discretion to protect victims of domestic abuse and crimes by identifying parole, deferred action, stays of removal, and motions to terminate or administratively close a case as possible tools.39

Two years later and in the absence of regulations on the U visa, DHS issued yet another memorandum to address U visa applications. On October 8, 2003, INS Associate Director of Operations William Yates declared that all U visa applications would be centrally processed at the VSC. The Yates Memo authorized the VSC to determine if an applicant was prima facie eligible for a U visa and to then place the noncitizen in deferred action status if appropriate. In fact, the Yates Memo advised that deferred action was usually appropriate: “By their nature, U nonimmigrant status cases generally possess factors that warrant consideration for deferred action.”40 Less than one year later, Yates issued another guidance document giving the VSC jurisdiction over all U visa cases, including those involving victims in removal proceedings. This policy was meaningful not only because it expanded the authority held by VSC to grant deferred action to victims who were prima facie eligible for a U visa, but also because it marked an agreement between USCIS and ICE whereby ICE would support the termination of a case after the VSC approved it for interim relief in the form of deferred action.41 While it may seem obvious that ICE and USCIS should work collaboratively on cases in which both share a piece of the jurisdictional pie, the bureaucratic and cultural divide between USCIS and ICE has lingered in ways so that such collaboration has been rare.42 Moreover, the flurry of guidance about how ICE should treat potential victims who are already in removal proceedings or with a removal order in hand demonstrates both the many enforcement stages in the immigration process where prosecutorial discretion should be considered and the variety of tools DHS employees have to exercise this discretion favorably.

After eight years of interim relief, USCIS finally began issuing U visas in 2008.43 Today, both the U and T visa categories enjoy a lengthy set of regulations and reams of supplemental documents to guide victims and advocates. Deferred action remains an important protection, especially for individuals who are eligible for a U or T visa in a year when the statutory cap has already been reached. USCIS has stipulated that individuals who are prima facie eligible for a U visa will be added to a waiting list if their petitions exceed the quota.44 These individuals will be granted deferred action or parole until a U visa becomes available. Likewise, guidance from ICE suggests that U and T visa applicants should not be prioritized for removal proceedings until a decision is made regarding their visa.45 According to USCIS statistics, the number of U visas approved in 2010, 2011, and 2012 exceeded ten thousand. These individuals were possibly granted deferred action or parole and were added to the waiting list.46 In December 2013, USCIS announced that the ten thousand statutory cap was reached again for 2013.47 During a stakeholder conference call, USCIS indicated that U visa applicants and qualifying family members who are found eligible for a U visa but placed on a waiting list because of the cap would be granted deferred action and eligible to apply for work authorization.48 Meanwhile, the number of principal T visas issued in each fiscal year has been less than one thousand (far lower than the statutory cap), meaning that very few if any eligible T visa applicants have required the deferred action remedy.49

Even with the new statutory protections, DHS continues to use prosecutorial discretion to assist victims who are eligible for formal protection but must wait for months or sometimes years for their immigration status to be processed. The wait time for these victims can be long if there are too few visa slots and too many victims. In addition, individuals who have clearly suffered abuse do not always qualify for a form of relief because they cannot meet all the corresponding statutory requirements. While a full discussion of the statutory remedies available for crime and trafficking victims is beyond the scope of this book,50 the existence of various prosecutorial discretion tools used by DHS to protect victims until they can avail themselves of formal remedies or because they cannot do so is important to understanding the use of prosecutorial discretion in the immigration system. The use of “deferred action” as a tool to aid VAWA, T, and U visa applicants further illustrates a recurring theme in U.S. immigration law and policy. Prosecutorial discretion has long been used as a stopgap measure to benefit persons who otherwise would be deprived of immigration benefits to which Congress has said they should be entitled. Although deferred action has long been a feature of the immigration system, the public has not always had access to information on how this remedy is used and the sheer magnitude of cases.

Analyzing Deferred Action Cases Retrieved through the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA)

To gain information about the use of deferred action, I requested through the Freedom of Information Act data about deferred action cases from Department of Homeland Security units beginning in 2009. Before this time, Leon Wildes, the lawyer for music icon John Lennon, made similar requests to INS and DHS in the early 1970s and early 2000s, respectively. The final section of this chapter looks at the cases Wildes and I reviewed after requesting and sometimes suing the immigration agency for information under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA).

In 1967, Congress enacted FOIA to prevent agencies from developing and applying “secret law.”51 For more than one year, Wildes, corresponded with INS to gain information about the INS’s deferred action program. Wildes was eager to review the body of cases approved for deferred action (or nonpriority status) in order to argue that Lennon should be considered for the same. Wildes eventually filed an FOIA lawsuit against INS to obtain this information.52

As a result of the FOIA lawsuit, INS provided Wildes with the histories of 1,843 granted deferred action cases. These cases provided him with the basis for arguing that Lennon should be granted deferred action. After examining the cases, Wildes calculated that deferred action functions as an important remedy granted to people with specific equities. In reviewing the adverse factors contained in the body of cases, Wildes also concluded that INS decided cases based largely on humanitarian factors as opposed to a person’s criminal history or actual deportation charge.53 He identified five primary humanitarian factors that drove deferred action approvals: (1) tender age, (2) elderly age, (3) mental incompetency, (4) medical infirmity, and (5) family separation if deported.54 The largest category of cases granted involved family separation.55 Typical of the granted cases was this one: “A representative case is 1-12, in which the subject was a Mexican national, without an immigrant visa, who had a permanent resident husband and several United States citizen children. The report states the expulsion would ‘[r]esult in the separation of subject from her children in the United States. She has no means of support in Mexico.’ Nonpriority status was granted despite her previous separation from her husband and the fact that she was on welfare.”56 A U.S. citizen or lawful permanent resident family member was involved in more than 80 percent of the cases granted.57 These data indicate that the presence of a family member with long-term ties to the United States heavily influenced whether the agency granted deferred action in a particular case.

Wildes also learned several interesting aspects of cases involving the rationale of “tender age.” He noticed that many individuals in tender age cases were teenagers or young adults when INS granted deferred action.58 This trend continues today, as DHS remains generous regarding age under the agency’s current DACA program. Under DACA, people are eligible to qualify for the program if they were under the age of thirty-one as of June 15, 2012.59

As to the 357 approved cases involving mental incompetency, Wildes astutely observed, “What is significant, if somewhat ironic, is that in most of these cases the grounds for deportability—e.g., mental defects, institutionalization after entry—are also grounds for nonpriority consideration because of the humanitarian factors involved. Thus the Immigration Service through its nonpriority program seems to be adding both flexibility and sensitivity to an otherwise indiscriminate and harsh law.”60 While mental illness is no longer a criterion for removal, it was still grounds for deportation at the time Wildes received his first body of cases. What he appropriately calls “ironic” supports the position that a person who is technically deportable for health problems or economic reasons may possess the very kinds of equities that are worthy of deferred action status.

Wildes also reviewed the “negative” factors present in the nearly two thousand approved deferred action cases. While he did not have access to the deferred action cases that were denied, the presence of negative factors in his data set is quite revealing as it shows that an adverse immigration history played a minor role in the granting of deferred action. Wildes deduced that “[n]onpriority has been granted to aliens who have committed serious crimes involving moral turpitude, [drugs], fraud, or prostitution. Moreover, nonpriority has been given to Communists, the insane, the feebleminded, and the medically infirm. In sum, nonpriority has been granted to those who have violated almost any provision of the Act.”61 To illustrate, Wildes offered the following case summary as “[t]he most convincing evidence of the relative unimportance of the ground of deportability—subject has a criminal record which includes convictions for auto theft, contributing to the delinquency of a minor, vagrancy (pimp), rape, burglary in the second degree, robbery, possession of narcotics, and numerous other arrests. Despite his lengthy criminal record and numerous grounds for deportability, he was granted nonpriority status based upon his subsequent good behavior, successful marriage, and the fact that deportation would result in the separation of a good family unit. Clearly this decision was reached through strict evaluation of humanitarian factors alone.”62 Because of Lennon’s history, Wildes was curious about whether people with a drug conviction fared well with the agency when they requested deferred action. If such cases existed, Wildes could argue that Lennon should receive nonpriority status. Wildes’s discovery and analysis of these first publicly revealed cases provided a body of precedent that could be cited by noncitizens desperate to remain in the United States for humanitarian reasons.

Deferred action continued to function as a form of relief after INS was abolished and DHS was created. However, the power to grant or deny deferred action was bestowed on three separate agencies within DHS. The decentralization of deferred action to three different agencies within DHS coupled with a post-9/11 culture of “no” may have impacted the transparency and volume of deferred action requests that were denied because of “bad timing” but in the “best of times” might have been approved. This is an unsupported assumption that I can base only on what I witnessed as a legislative lawyer in Washington, D.C., immediately after 9/11 and on the striking drop in deferred action cases and data available to the public, even with an FOIA request. The next section summarizes the data DHS has provided on deferred action and begins with a second quest by Leon Wildes. This time Wildes filed new FOIA requests to three USCIS regional offices for all records of cases in which deferred action was granted.63 He received information from two of the three regions (Central and Eastern). In total, he received information about 499 deferred action cases.64 Wildes found that roughly 89 percent of the cases were approved for deferred action.65 As in his 1976 article, Wildes found that USCIS granted deferred action based on a strict set of criteria.66 In most of the cases reviewed by Wildes, each decision took the form of a terse statement and omitted the overriding factors influencing the decision.67 Nevertheless, grants of deferred action fell within seven specific categories: (1) separation of family, (2) medically infirm, (3) tender age, (4) mentally incompetent, (5) potential negative publicity, (6) victims of domestic violence, and (7) elderly age.68 Possible separation from family continued to be an overriding factor in deferred action grants.69 Nearly 30 percent of the cases involved family separation,70 and more than 20 percent of the cases granted involved someone with a medical infirmity.71 Cancer and HIV were common ailments listed in the medical cases.72 The data once again confirm DHS’s reliance on humanitarian criteria in granting deferred action.73 Wildes observes, “In light of the fact that these cases involve alien spouses who are completely reliant on public assistance and receive state-funded medical care, it is striking that the government approved them for deferred action status. This fact exemplifies that the humanitarian goal of deferred action takes precedence over the usual concerns of the INS, which removes aliens who have become a burden upon United States resources and thus have become subject to the public charge provision, another distinct ground removal.”74

Some of the cases analyzed by Wildes also included the factor of “potential negative publicity.”75 One report reads,

A nineteen-year-old Mexican [was] adopted at age three and then shuffled among several families from the age of six. . . . In fact, for one extended period as a young child he lived alone in an abandoned house next to a large family with fourteen children who gave him food but had no room for him to live with them. During another period of time he lived alone in a storage shed on a large ranch where he worked in the fields. . . . In the fifth grade his “foster” mother reclaimed him . . . she abandoned him shortly thereafter. . . . He has had several years of perfect school attendance, achieved outstanding grades, distinguished himself as an athlete and leader who inspires others, and acquired a craft at which he has become very proficient and by which he has supported himself for long periods of time. . . . Given the number and breadth of persons in our communities who support this young man’s opportunity to remain in the U.S. and attend college, INS may be assured of SIGNIFICANT ADVERSE PUBLICITY if some form of relief is not found. No other form of relief is known.76

INS chose to grant relief to this young man. The data reveal that separation from family and negative publicity coupled with other factors such as a medical condition influenced grants of deferred action.

To update the research conducted by Wildes, I sought deferred action records from USCIS beginning in 2009.77 On June 17, 2011, I received a response to my FOIA request in the form of three compact discs,78 which together contained a cover letter, a 270-page document containing data, and several spreadsheets listing statistical data.79 More than 125 involved Haitian citizens who entered the United States after the 2010 earthquake.80 Much of the data on these cases lack information about the facts and/or outcome. For example, one log read, “[T]hirteen-year old girl came to the U.S. with her seventeen-year old sister; house destroyed by earthquake; living with USC aunt and legal guardian in the U.S.; attending school in the U.S.” Another log read, “Entered U.S. on B-2 visa with two daughters, one a USC; owned warehouse in Haiti that was destroyed by the earthquake; many customers killed in quake; living with brother in U.S.”81 I was not the only person to note the use of deferred action to benefit victims of Haiti’s earthquake. As to the deferred action cases stemming from the earthquake in Haiti, the DHS ombudsman observed, “Over the past year, stakeholders expressed concerns to the Ombudsman’s Office regarding the delayed processing of numerous deferred action requests submitted by Haitian nationals following the earthquake in January 2010.”82 In many instances, no other remedy existed to resolve these victims’ dilemma, and so deferred action was the only tool available.

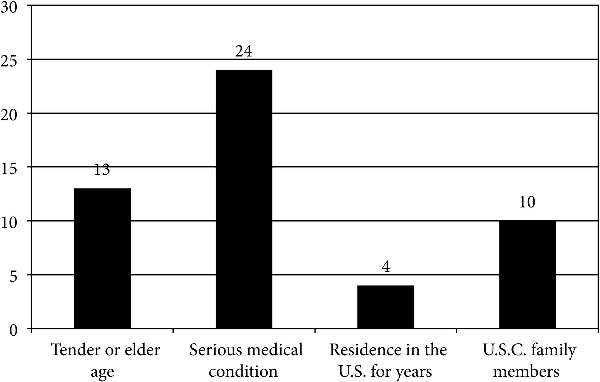

The remaining qualitative data I received from USCIS in 2011 included 118 identifiable deferred action cases, of which 107 were classified as approved, pending, or unknown.83 Among these 107 cases, 50 involved a serious medical condition, 19 involved cases in which the applicant had U.S. citizen family members, 22 involved persons who had resided in the country for more than five years, and 32 involved persons with a tender or elder age. Many of these cases involved more than one “positive” factor. For example, many of the cases involved both a serious medical condition and U.S. citizen family members, or involved both tender or elder age and a serious medical condition. The 48 granted cases fell in roughly four categories: (1) advanced or tender age, (2) serious medical condition, (3) residence in the United States for a number of years, and (4) U.S. citizen family members. Figure 4.1 provides a breakdown of noncitizens granted deferred action in these four categories. Many of these cases involved more than one positive factor. For example, deferred action was granted to a father of an eleven-year-old daughter who was a U.S. citizen and suffered from severe heart problems. Deferred action was granted to a forty-seven-year-old schizophrenic who overstayed his visa, was the son of a lawful permanent resident parent, and had siblings who were U.S. citizens.84 The 2011 data from USCIS revealed that the immigration agency uses many of the same criteria as during the Lennon era in determining whether deferred action is appropriate and also the truly compelling nature of many of these claims given that some cases often involved more than one humanitarian factor.

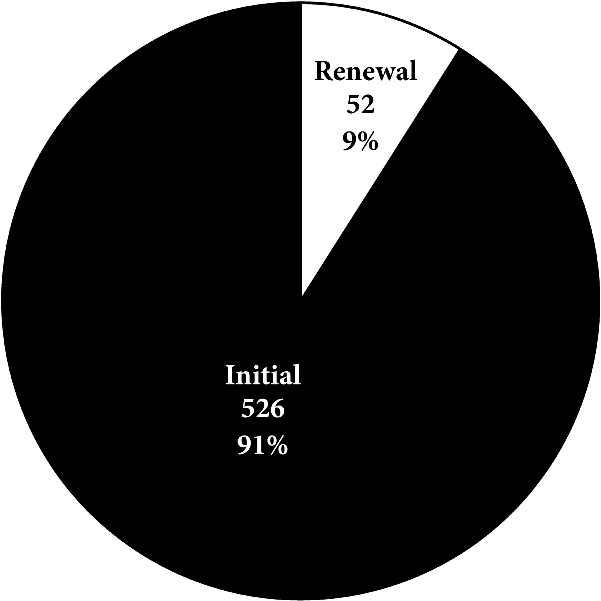

In May 2013, I filed new and updated requests for deferred action records and cases with USCIS.85 In September 2013, following a phone call from and supplemental letter to USCIS narrowing the scope of my FOIA request, I received a spreadsheet of deferred actions for a four-month period.86 The data contained information from four USCIS regions, with points such as the jurisdiction or USCIS office where the case was processed, basis for the request, manner of entry, nationality of the individual making the request, summary of the facts, and the outcome.87 The “Basis” column indicated whether the individual was requesting deferred action for medical, family, or other reasons. The “Summary” column contained specific information about the case. For example, four cases involved individuals from Nigeria, presumably from the same family where one of the family members had cancer. The four individuals were granted deferred action for a period of two years. Another case involved a Mexican female who entered the United States without inspection and had two children who were U.S. citizens. One of her children had Down syndrome and other serious medical issues. This mother was also granted deferred action for a period of two years, as was the father. The data set included about 578 deferred action cases, 52 of which were “renewals,” meaning that the individual had received deferred action in the past and was seeking an extension. Of note, 336 of the deferred action cases contained in this data set were based on a medical issue. Whereas most of the cases were labeled with one qualifier such as “family” or “medical,” a few of the cases listed more than basis for the deferred action request such as “family/medical.”88

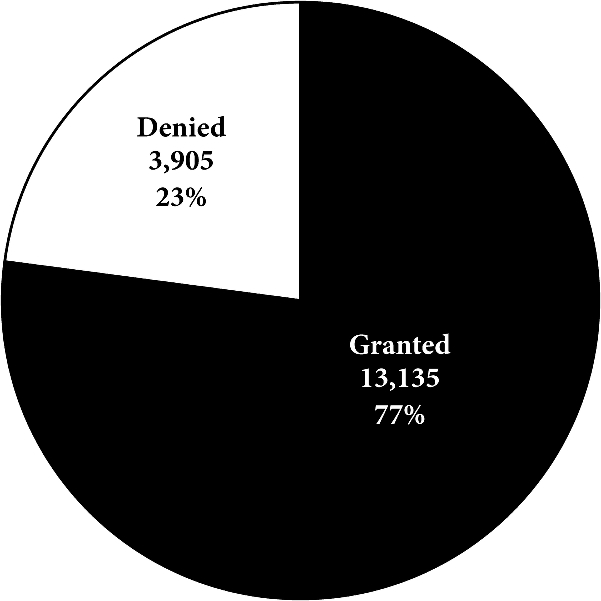

Of these 578 cases, 233 (40 percent) were granted deferred action. The 233 granted cases fell into roughly three categories: (1) family, (2) medical, and (3) other. Of these 578 cases, 181 (31 percent) of these cases were denied deferred action.

More than eighty-four nationalities were represented in the sample size provided by USCIS. As Table 4.1 demonstrates, nationals from ten of these countries enjoyed 120 or 52 percent of the deferred action grants processed by USCIS during this four month time period.

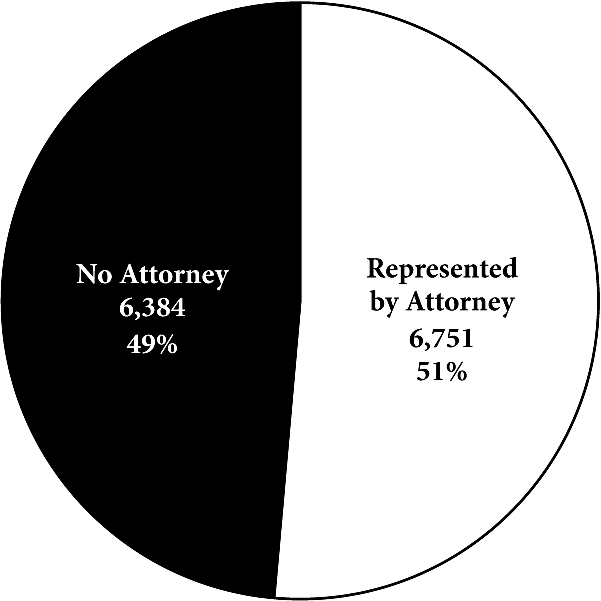

As explained earlier, any person who is granted deferred action may be eligible to apply for work authorization with USCIS if he or she can show economic necessity.89 Through FOIA, I received the data of work authorization applications processed by USCIS between June 17, 2011, and June 4, 2013, based on deferred action.90 The data indicate that 17,040 work authorization applications processed by USCIS were made pursuant to a grant of deferred action. Of these, 13,135 were approved, meaning that more than three-quarters of deferred action grantees were provided work authorization by USCIS. Of the total cases, 6,751 applicants were represented by an attorney or representative. Another 6,384 of these approved cases involved an applicant but no attorney. Interestingly, this number might indicate that several applicants were requesting deferred action (or at least the work permit associated with a deferred action grant) on their own. Of the 13,135 approved cases, 8,058 were females and 5,072 were male applicants. Of the approved applicants, the gender was unknown in 5 cases. Also unknown was how many of these cases originated with ICE, meaning that ICE granted the actual deferred action request but the individual grantee submitted a work authorization request to USCIS. Also uncertain were the number of cases that involve U, T, and VAWA applicants eligible for an actual benefit based on their victim status but waiting out their period in deferred action until a visa becomes available. It is reasonable to conclude that the data set does not reflect DACA cases that were processed for work authorization as applicants have been advised by USCIS to apply for work authorization using a different code.91 Notably, the data set does contain data points such as the duration of status, the applicant’s country of citizenship, and the status of the deferred-action-based work authorization application. While deferred-action-based work authorization requests were made by citizens from over 150 countries, most requests were made from citizens of Mexico, Colombia, Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala.92

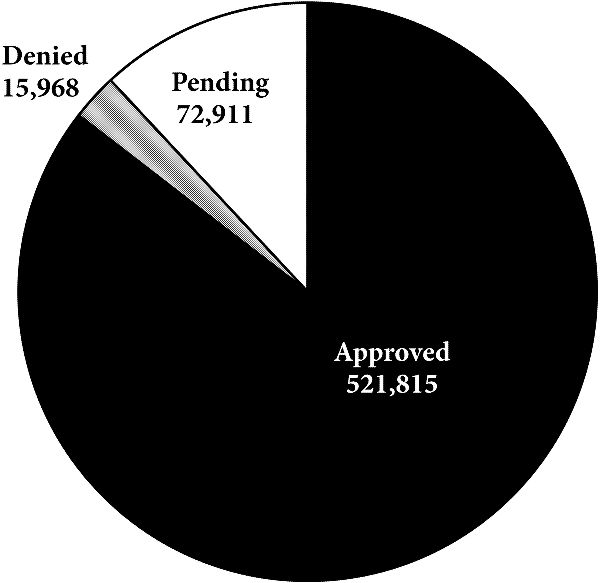

Fig. 4.2. Deferred action cases processed by USCIS during a four-month period, 2013.

Fig. 4.3. Outcome in deferred action cases processed by USCIS during a four-month period, 2013.

Fig. 4.4. Outcome in work authorization applications adjudicated by USCIS pursuant to a deferred action grant, June 17, 2011, to June 4, 2013.

Fig. 4.5. Percentage of individuals represented by counsel in work authorization applications adjudicated by USCIS pursuant to a deferred action grant, June 17, 2011, to June 4, 2013.

Fig. 4.6. Outcome in Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals requests processed by USCIS through the first quarter of 2014. USCIS: http://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/USCIS/Resources/Reports%20and%20Studies/Immigration%20Forms%20Data/All%20Form%20Types/DACA/DACA-06-02-14.pdf.

Beyond the individual deferred action data received through FOIA requests, USCIS has published its data about the more publicized DACA program on its own. Data processed through the first quarter of 2014 reveal that USCIS received 638,054 applications for DACA, of which more than 610,694 were accepted for review. During this time period, 521,815 DACA applications were approved, 15,968 were denied, and 72,911 are still pending.93 The top five countries from which DACA applicants hail are Mexico, El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala, and Peru.94 The top five residences associated with DACA applications are California, Texas, Illinois, New York, and Florida.95 Public policy groups like the Migration Policy Institute and the Center for American Progress have analyzed DACA data even further.96 For example, one report by the Center for American Progress, titled “Undocumented No More,” distills information on 465,509 DACA applications obtained through two FOIA requests to DHS.97 Below are some of the findings made by the center:

• The DACA implementation rate among the states varies significantly, from a low of 22 percent of eligible people in Florida to a high of 48.6 percent in Indiana. Note that because a portion of the DACA population will not be immediately eligible to apply, individual state implementation rates should not necessarily be viewed as low.

• Nationally, 53.1 percent of the DACA population is immediately eligible.

• Women represent 51.2 percent of the FOIA sample; men represent 48.7 percent.

• The average age of a DACA applicant in the FOIA sample is twenty years old, and older applicants are more likely than younger applicants to be denied.

• Mexican applicants are half as likely to be denied DACA as other groups. DACA applicants in the FOIA sample were born in 205 different countries, from the Democratic Republic of the Congo to Luxembourg and from Norway to North Korea.

• Mexicans make up 74.9 percent of the FOIA sample; Central Americans, 11.7 percent; and South Americans, 6.9 percent. Altogether, applicants from Latin America compose 93.5 percent of the total.98

Analyzing Deferred Action Cases at ICE

USCIS is not the only agency in DHS with the authority to grant deferred action. ICE also grants such cases, but their data were elusive until recently. I filed my first FOIA request to ICE in October 2009 asking for all records and policies involving prosecutorial discretion. However, ICE closed my request in December 2009. Nevertheless, I filed a new request in March 2010 requesting specific information about all deferred action cases. After corresponding with ICE about the status of my request on multiple occasions, I received a slim response in January 2011 in the form of a single chart listing a handful of active ICE grants of deferred action between 2003 and 2010. ICE provided no further detail.99 The chart itself lacked any detail about the deferred action process, the factors used by ICE to grant or deny deferred action, and any explanation to demonstrate that the universe of deferred action cases presented in the chart was in fact accurate.100

Concerned in part that ICE did not make a complete search, I filed an appeal on March 29, 2011, hoping to receive more data.101 ICE denied the appeal on September 27, 2011, concluding that, even after a further search, there were no records responsive to my request.102

After some deliberation, I filed an FOIA complaint in federal court, seeking all ICE records concerning prosecutorial discretion and deferred action.103 Between June 2012 and September 2012, the DOJ and ICE attorneys assigned to my case and I discussed the nature of the records I was requesting and the limitation ICE had in providing records for deferred action cases prior to fiscal year 2011, or for producing entire case files for deferred action cases in any year.104 Ultimately, we were able to settle the case without a trial, and the case was dismissed on October 1, 2012.105

Highlights from Data Collected between October 1, 2011, and June 30, 2012106

• ICE did not formally track deferred action case statistics prior to fiscal year 2012.

• ICE processed 4.5 times as many stays of removal as deferred action cases.107

• ICE processed 698 deferred action cases, of which 324 (46 percent) were granted between October 1, 2011, and June 30, 2012.

• The composition of deferred action cases among field offices varied significantly. More than one-half of the 698 deferred action cases granted were concentrated in the above five field offices.

• There were 78 nationalities (including “unknown”) represented in the deferred action cases covered in this study. The single largest country of citizenship represented in deferred action cases was Mexico, followed by Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, and Jamaica. Mexico also had the highest number of deferred action grants.

• The five primary humanitarian factors (excluding “other”) identified in granted deferred action cases were presence of a U.S. citizen dependent, presence in the United States since childhood, primary caregiver of an individual who suffers from a serious mental or physical illness, length of presence in the United States, and suffering from a serious mental or medical care condition.

• The single largest adverse factor contributing to a deferred action denial was “lack of compelling factors,” which occurred 207 times (55 percent). Only 69 cases (18 percent) were denied because of a criminal history.

• Individuals from different age groups were considered for deferred action, and not limited to the age group that qualifies for DACA, the very young, or the elderly.

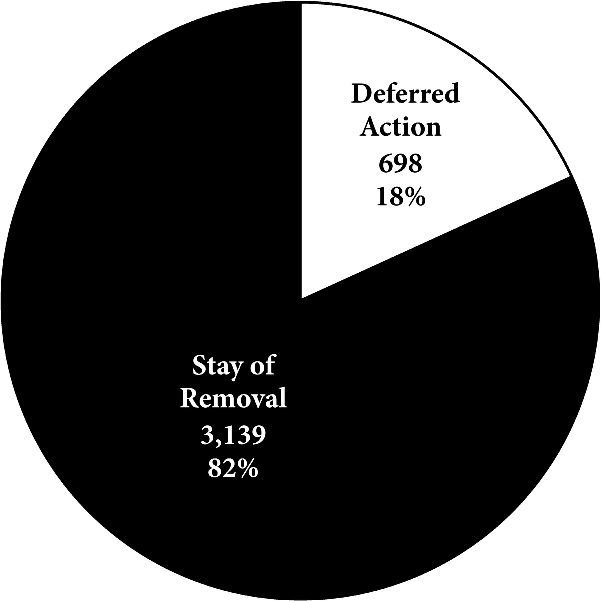

As part of the settlement, ICE provided me with deferred action data collected from all twenty-four of ICE’s Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO) field offices.108 ICE Headquarters collected the data from each field office. The data included cases processed between October 1, 2011, and June 30, 2012. ICE also provided data on applications for “stays of removal” from all twenty-four ICE ERO field offices.109 An administrative stay of removal is a form of prosecutorial discretion and, like its deferred action cousin, enables a noncitizen without legal status to apply for protection from removal and possible work authorization.110 However, unlike deferred action, a stay of removal is available to the noncitizen only after a removal order has been entered and may be granted only by ICE.111

The data yielded a total of 3,837 cases,112 698 of which were deferred action cases while 3,139 were stay of removal cases. Of the 698 deferred action cases, 324 were granted. Of the 3,139 stay of removal cases, 1,957 were granted.

Fig. 4.7. Total number of deferred action cases and stay of removal cases processed by ICE, October 1, 2011, to June 30, 2012.

Humanitarian and Adverse Factors Identified in Deferred Action Cases

Many of the factors identified by DHS policy guidance like Morton Memo I were identified in the 698 cases granted deferred action. While the data provided by ICE contain a field titled “Reason for Grant/Denial,” each field contained only one factor for each entry. Therefore, the total number of reasons given (including “other”) is exactly equal to the total number of cases reported. The five primary factors (excluding “other”) identified in granted cases were the following:

• Presence of a U.S. citizen dependent

• Presence in the United States since childhood

• Primary caregiver of an individual who suffers from a serious mental or physical illness

• Length of presence in the United States

• Suffering from a serious mental or medical care condition113

Fig. 4.8. Most common reasons for a deferred action grant processed by ICE, October 1, 2011, to June 30, 2012.

The data from ICE did not identify the factors leading to the greatest number of deferred action “grants” (“Other”), which raises procedural questions about whether ICE should be including additional fields in its data collection.114 Thirty cases, or 9 percent, were identified as based on the individual’s “serious mental or physical illness.” While 9 percent appears low in contrast to the types of cases that have historically involved a serious medical infirmity of mental health condition, the overall reasons identified for deferred action in this data set were consistent with the categories of cases that have historically been granted deferred action.

The data provided by ICE confirm that field officers are required to identify a factor in denying deferred action, but the data fields themselves (e.g., “Lack of compelling factors”) are not detailed enough to allow for a meaningful analysis of why a particular case was denied. As illustrated by the data, 69 among the 374 denials were based on a criminal history, while 207 cases were denied because of a “lack of compelling factors.” The most common factors (excluding “other”) for denials of deferred action were these:

Composition of Deferred Action Cases among Field Offices

There was significant variance in the number of deferred action and stay of removal cases processed among field offices, which processed anywhere from 38 to 720 of these cases during the period covered. For example, the data show that the Miami office processed a far greater number of deferred action and stay of removal cases in contrast to the other twenty-three field offices. The field offices with the highest number of such cases included the following: Miami (720 cases), Newark (341), New York City (276), Washington (253), and San Francisco (203).

An explanation for why ICE processed a far greater number of stays over deferred action cases is elusive at best but may be explained by the fact that stays of removal enjoy more predictability and accessibility for the ICE employee. Unlike deferred action, a stay of removal is grounded in the immigration regulations and furthermore includes a form and a fee; this likely makes it easier for ICE to track the case and for the employee to justify the decision. Likewise, a stay of removal is a form of relief granted only after a final order of removal is entered, whereas the deferred action remedy may be considered at any stage of the enforcement process and therefore may be viewed by ICE as a riskier decision, especially early in the enforcement process. Finally, a stay may be viewed as more “temporary” in nature than deferred action because “deferred action” is more politically controversial.

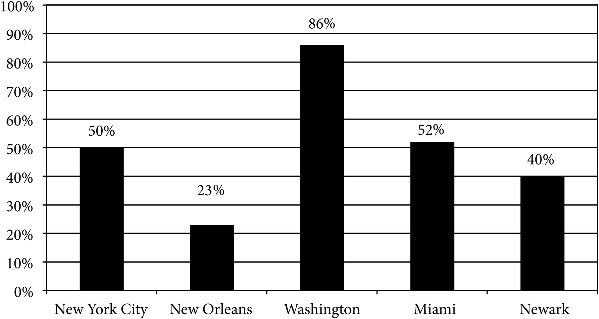

Looking just at deferred action cases, the composition of deferred action cases among field offices also varied significantly. The field offices with the highest number of deferred action cases were as follows: New York City (50 percent granted), New Orleans (23 percent granted), Washington (86 percent granted), Miami (52 percent granted), and Newark (40 percent granted). The Washington field office had the highest percentage of deferred action cases that were granted among the field offices that had more than fifteen cases.

The Washington field office had the highest number of grants for deferred action by a field office, granting it for 65 of the 76 cases. The most common factors identified for grants at the Washington field office were (1) primary caretaker of an individual who suffers from a serious mental or physical illness, (2) U.S. citizen dependent, and (3) individual present in the United States since childhood. The second highest volume of grants took place in the New York field office. Specifically, 52 of the 104 deferred action cases were granted in New York. The most common factors identified for New York were (1) other, (2) U.S. citizen dependent, and (3) the individual’s length of presence in the United States. Notably, none of the deferred action cases granted in New York were identified as based on a serious mental or physical illness, which historically has driven many deferred action grants.

Fig. 4.9. Five ICE field offices with the highest deferred action grant rate, October 1, 2011, to June 30 2012.

Certain field offices had a higher volume of deferred action applications as well as granted cases. The disparity in the distribution and outcomes might be explained by the fact that deferred action requests to ICE are normally made to the field office that lies within the jurisdiction of the applicant’s residence and that potential applicants for deferred action are concentrated in specific locations. Notably, the jurisdictions covered by the Washington, New York, and Miami field offices have large unauthorized immigrant populations.115 An additional explanation for the differences is that deferred action cases are more successful with ICE when the noncitizen is represented or assisted by an attorney. Also, there may be a higher rate of deferred action grants in areas where there are higher concentrations of immigration attorneys.

The findings outlined above improve transparency by providing potential applicants and attorneys who are working on deferred action cases with information such as “how an office handles cases involving a serious medical condition.” These findings also reveal that ICE has limited ways in which the information about deferred action cases is sorted, as there is no explanation for which factors contribute to the “Other” category, which appears to be the largest basis for a deferred action grant. There is also no explanation for what constitutes a “lack of compelling factors,” which appeared to be the single greatest basis for a denial in deferred action cases.

Perhaps more important, the findings do not include an analysis of how a negative factor interacts with a positive one. For example, how does ICE treat someone who has a criminal history and a U.S. citizen dependent? This kind of information is vital as it contributes to the public understanding about whether having a criminal history is fatal or just a factor behind a deferred action determination. Based on the information that we do have, the basis for a grant appears to rest more on the positive equities of the individual, many of which have served historically as the basis for deferred action. To recap, the most common reasons given for a deferred action grant in the 324 cases include having a U.S. citizen dependent, being an individual in the United States since childhood, being a primary caregiver of an individual who suffers from a serious mental or medical illness or has a longtime presence in the United States.

Distribution of Deferred Action Denials across Field Offices: Five Field Offices Had a Significantly Higher Number of Denials than the Average Denial Rate at Field Offices

The data provided by ICE show that the New Orleans field office had the highest number of cases denied deferred action—75 out of 97 cases. The most common factors identified in the New Orleans data were (1) lack of compelling factors and (2) criminal history. Though the New York field office was identified as the location with the second highest number of deferred action grants, it also came in as yielding the second highest number of denials (52 out of 104 deferred action cases were denied). The most common reason for the cases denied in New York City was a lack of compelling factors. Notably, only one of the denials was identified as having been based on a criminal history.

Disparities in the Outcome of Deferred Actions by Field Office

I was interested to look at how field offices fared in contrast to the overall mean or average rate of denial and grant in deferred action cases. There was significant deviation from the mean at several field offices. Of the 649 deferred action cases at field offices with at least 15 cases, the mean grant rate was 44.5 percent, while the mean denial rate was 55.5 percent. While 15 cases is a rather small sample size, the disparity is notable. The data show that eight offices deviated from the mean by more than 20 percent.

The variance in deferred action cases among field offices signals disparity and challenges the quality of the program. Administrative law designs have been traditionally examined under values like efficiency, consistency, accuracy, and acceptability. When deferred action decisions are disparate, this leads to uncertainty about whether decisions are achieving these values.116 In particular, when the agency makes different decisions about people who have similarly relevant facts, this can be viewed as unfair and an abuse of discretion. One complexity, and there are many, is to pin down whether such disparity reflects an abuse of discretion or whether the difference in outcome falls within the range of acceptable legal discretion. Likewise, there may be additional variables in each field office that are contributing to different outcomes. For example, it may be that the cases handled in the Washington office include those with stronger facts, greater compelling equities, and fewer negative points or more minimal criminal histories.117

Fig. 4.10. Deferred action grant rate by ICE field office versus national average, October 1, 2011, to June 30, 2012.

Composition of Deferred Action Cases by Nationality

There were more than seventy nationalities represented in the deferred action cases collected between October 1, 2011, and June 30, 2012. Nationals from Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador enjoyed the greatest number deferred action grants during this time period.

Age of the Individuals Processed for Deferred Action and Stays of Removal

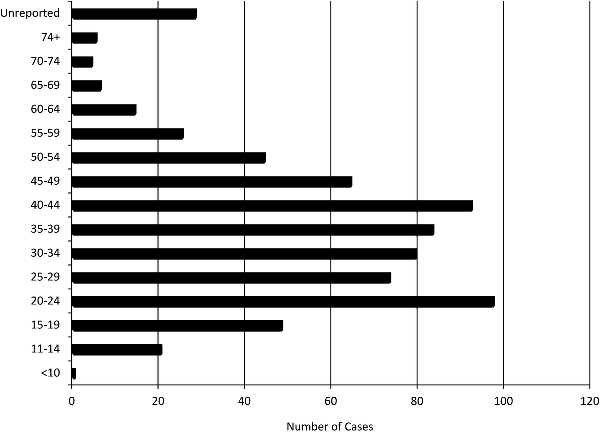

The age of the individuals processed for deferred action and stays of removal was calculated by reviewing the birth date of the individual and the date of the decision. Figure 4.11 offers an overview of the age groups in the data collected by ICE. The age of applicants was distributed almost in a bell-shaped curve, which is not entirely surprising given the sample size of 3,387.

Fig. 4.11. Age of applicant for deferred action requests processed by ICE, October 1, 2011, to June 30, 2012.

Looking specifically at the age groups for deferred action cases, figure 4.11 shows that individuals between the ages of twenty and twenty-four (98 cases or 14 percent) were processed at a greater rate than any other age group. The data illustrate that individuals from different age groups are considered for deferred action, and that it is not limited to the age group that qualifies for DACA, the very young, or the elderly.

On the other hand, it may also be the case that the agency treats “tender age” with a broad lens, looking less at the age of the applicant at the time of the decision, for example, and instead at the age at the time of entry. The data provided by ICE do not contain a field for the date of entry or for the number of years the individual has resided in the United States. As such, it is not possible to determine whether there are more individuals of tender or advanced age at the time of entry in contrast to what is reflected in Figure 4.11. Also of note is the possibility that many of the cases were granted deferred action because of a U.S. citizen dependent who was a family member of tender or advanced age even if the recipient of deferred action was not labeled as such.

Looking at whether age played a role in the outcome of a deferred action case, the data reveal a diverse distribution of grants and denials among age groups, with two exceptions: individuals who were younger than nineteen or older than sixty-five at the time of the decision were granted at a higher rate (78 percent) than the average (58 percent). This suggests that in these extreme cases, individuals with a tender or advanced age actually were treated more favorably by the agency.

Making the Case for Notice and Comment Rule Making for Deferred Action

As I sought data on DHS records of deferred action, one aspect of the deferred action process jumped out at me: there was no administrative transparency connected with the process, and it was impossible to determine whether deferred action was being used wisely or widely. In large part, this was because deferred action was invisible to the normal procedures outlined in the Administrative Procedure Act. Administrative law icon Kenneth Culp Davis declared the notice and comment rule-making procedures of the Administrative Procedure Act “one of the greatest inventions of modern government” and advocated for greater rule making in order to increase public participation in and judicial review of agency decisions and policy.118 This section analyzes the virtues for enacting a rule on deferred action. The concept of rule making comes from a bill enacted by Congress in 1946 known as the Administrative Procedure Act (APA).119 The APA contains multiple sections related to the rule-making process. Under the APA, notice of proposed rule making by the agency must be published as a public document in the Federal Register or personally served on affected individuals not less than thirty days before the effective date of the rule.120 The APA also requires that individuals be given an opportunity to comment on a proposed rule, after which the agency is required to consider relevant factors and include a statement of purpose in the newly minted rule.121 Many of the immigration documents issued by DHS are subject to an “exception” of this rule-making requirement. Specifically, the APA contains the following exceptions to the substantive rule-making requirements: (1) interpretative rules, general statements of policy, or rules of agency organization, procedure, or practice; or (2) when the agency shows that public procedures thereon are impracticable, unnecessary, or contrary to the public interest.122 General statements of policy are issued by all levels of the agency, and can be created in a variety of formats such as a “policy letters,” “press releases,” “questions and answers,” and “memoranda.”123 During its tenure, DHS has issued hundreds of policy statements bearing similar titles. Many of DHS’s prosecutorial discretion policies have been published as a “memoranda” and treated by the agency as “general statements of policy,” excepting them from the APA rule-making requirements. Thus, little transparency exists with regard to the process or the decision-making factors.

Whether a policy operates as a “rule” or a “general statement of policy” is not always guided by its label, but instead rests on the practical function and impact of such a policy. One notable case in which the court found that a policy of the Food and Drug Administration operated as a rule subject to notice and comment rule making is Community Institute v. Young.124 Community Institute represented a group of organizations and private citizens challenging the Food and Drug Administration’s regulation of contaminants (in particular, aflatoxin) in corn. While the statute at hand limited the amount of “poisonous or deleterious substances” in food, the FDA created a policy directed at food producers. The “policy” instructed that producers that contaminated above the action level would be subject to enforcement proceedings by the FDA. The court held that the FDA’s policy for limiting the toxin levels in corn was a legislative rule because “FDA by virtue of its own course of conduct has chosen to limit its discretion and promulgated action levels which it gives a present, binding effect. Having accorded such substantive significance to action levels, FDA is compelled by the APA to utilize notice-and-comment procedures in promulgating them.”125 One critic of the outcome in Young has argued that the court created a disincentive for agencies to self-regulate.126 While it may be true that a strongly administered internal rule can suffice to ensure that agencies follow the rule, I cast doubt on whether the DHS can achieve the same level of consistency and fairness in deferred action cases without notice and comment rule making.

Deferred action has not been subject to notice and comment rule making because deferred action was first implemented through an INS Operations Instruction, which the courts have generally held are internal guidelines or general statements of policy.127 One exception is the Ninth Circuit case Nicholas v. INS, which found that the Operations Instruction operated like a substantive benefit: “It is obvious that this procedure exists out of consideration for the convenience of the petitioner, and not that of the INS. In this aspect, it far more closely resembles a substantive provision for relief than an internal procedural guideline. . . . Delay in deportation is expressly the remedy provided by the Instruction. It is the precise advantage to be gained by seeking nonpriority status. Clearly, the Operations Instruction, in this way, confers a substantive benefit upon the alien, rather than setting up an administrative convenience.”128 This history is important to understanding the legitimacy of recognizing deferred action as a benefit and the moves INS made to modify the Operations Instruction to avoid such recognition.

As recounted earlier, the INS modified the Operations Instruction in 1981 to clarify that deferred action was a discretionary act as opposed to a formal benefit. Treating the Operations Instruction as a general statement of policy allowed the INS to amend and remove the once “mandatory” nature of the Operations Instruction without public notice or comment. Likewise, it permitted the courts to uphold decisions by the agency to deny deferred action status to particular individuals regardless of their equities. Finally, the court discussion as to whether the Operations Instruction constituted a substantive rule inspired the explicit language contained in current agency memoranda that prosecutorial acts are discretionary, immune from judicial review, and under no terms an “entitlement” to the noncitizen.

Courts have continued to interpret deferred action as a general statement of policy exempt from the APA’s notice and comment requirements. And yet the cases analyzed in this chapter illustrate that the agency has long used specific criteria to both adjudicate deferred action cases and enable individuals to avoid removal and remain in the United States with dignity through grants of deferred action. Deferred action may officially walk like a “discretionary act,” but to individuals who are granted this remedy it quacks like a substantive benefit.