Chapter Eighteen

It was only a matter of time before Diana found out about Judy and me. And when she did, in the autumn of 1991, she was, understandably, furious. We were leading virtually separate lives, but she hated the idea of me living in the flat while seeing someone else on a regular basis. I had broken our pact not to get ‘heavily involved’ and she was not going to put up with it. She suggested we went out to dinner for a ‘summit’ meeting. And she laid the law down.

‘We need a rest from each other, Charlie,’ she said. ‘I would prefer you to leave, but, if you’re not going to, we have got to distance ourselves from each other.’

I was in a quandary: I did not want to leave the flat; but I could not bear the thought of not having Judy in my life, either. In the end, I stayed in the flat, but the atmosphere between Diana and me was ice cold. Even the brother and sister relationship had vanished. When we were in the flat together, we rarely talked. When we did, we were merely polite, not loving. After all we had been through, it was awful. But I could not see a way out, without throwing in my lot with Judy and asking to move in with her, which I did not feel was right. Apart from anything else, she had three children, which meant that space at her semi-detached was tight. I did stay there at weekends, however. I would pack my bag on Friday and stay with Judy in Sanderstead until Sunday night. By now, all the money I had had from the film had gone, but having little money to go out on the town did not bother me. When two people are in love, they can be happy just being together, doing nothing in particular. Judy and I did go to a nightclub in Croydon some nights, but we were at our happiest staying in, watching all the new movie releases on video, with a bottle of wine. Judy had always been a white-wine person, but I had introduced her to red, and, now she drank it all the time.

Despite her own love for me, Judy did try to help me sort it out with Diana. She even wrote to her, stressing that I still felt a lot, and urging us to resolve things between us. Judy, bless her, said she would disappear from my life if I felt Diana and I could make a go of it, and we did have a break from each other for a while. But I knew it was over with Diana. I was even more deeply in love with Judy and knew I wanted to spend the rest of my life with her and her children.

Sadly, I didn’t have the courage to make a choice, preferring to let the women make it for me. I was weak and I regret it, because all it did was leave us all in a miserable limbo, each realizing that something must be done, but none of us knowing what.

My son, Gary, knew and liked both Diana and Judy and would have been embarrassed by the situation. But he was in Blackpool helping out at the Verona Hotel, run by friends of ours, Paul Jonas and his wife, Susie. Paul and I had got on well from the moment we met at Chatterly’s Club, in Mayfair, in 1982, and when he and Susie bought the Verona six years later, there was an open invitation to Gary and myself to stay there whenever we wanted. I did not take up the offer very often because I was happy enough living the high life in London, but when Paul suggested my son stayed at the hotel long-term, helping out with the chores in return for board and lodging, Gary jumped at the chance.

What a haven Blackpool was for him: after we all saw in the New Year at the hotel in 1989, he stayed there, on and off, for three years. Paul and Susie liked Gary’s gentle nature and willingness to do whatever was asked of him and they insisted on throwing a party for his fortieth birthday in July 1991. I’m sure Gary was at his happiest up north. The clean, fresh sea air was an obvious attraction for anyone who has spent most of their life in the smoke and grime of London, but for Gary it was more than that. Paul and Susie, and their son, Nikki, treated him as one of their own, and Gary revelled in being part of a warm family environment. When he wasn’t changing beer barrels, cleaning bedrooms or waiting up to let in late arrivals, he was drinking Bacardi and Coke in the hotel bar with all sorts of people, including showbiz personalities, such as Frank Carson, Brian Conley and the Nolan Sisters, and it suited him down to the ground.

For a couple of years, Ronnie’s marriage to Kate was fine. She visited him regularly and, like the dutiful wife, did her best to make him as happy as she could. She was always on time for visits, stayed the allocated two hours and was meticulous in relaying all kinds of messages to Ronnie’s friends and acquaintances beyond Broadmoor’s walls. She had even brought her sister, Maggie, to Broadmoor to meet Ronnie’s closest friend there, Charlie Smith. And they had got on so well, a romance blossomed that led, eventually, to marriage. But then, during one of my visits just before Christmas that year, Ronnie admitted he was beginning to see a side of Kate he had not seen before – a side he did not like.

‘What exactly do you mean?’ I asked.

‘She seems very money conscious,’ he said.

‘Aren’t we all?’ I said.

‘But it’s all she ever thinks about. Every time I see her, it’s money, money, money all the bleedin’ time.’

I didn’t know what to say. We all like money; all need it. And, to be fair, Ronnie liked it as much as anyone, even though he was locked up and didn’t need it as much as the rest of us.

‘What do you think of her, Charlie?’ Ronnie asked.

I wasn’t going to be drawn into that one. Whatever I said was bound to be wrong; after all, Kate was Mrs Ronald Kray and it wasn’t for me to criticize another man’s wife, even if she was my sister-in-law.

‘I don’t really have an opinion, Ronnie,’ I said. ‘I don’t know the girl well enough.’

‘I’m wondering whether she doesn’t really care for me and only went through with the marriage to cash in on the publicity, or to get some kind of reflected glory.’

Again, I said, I didn’t know; it was their business. But what I did know, was certain of, driving up the M3 towards London that evening, was that Kate spelled Trouble with a capital T.

In many ways, Broadmoor was good for Ronnie, and he was happy there. But there were times when he was treated in an off-hand manner, as though he was still a violent gangster, not a sick patient; as though they could do anything they liked and to hell with what he or anyone else thought.

One morning, we greeted each other in the visiting hall and I knew at once he was upset.

‘What on earth’s the matter?’ I asked.

‘They’re trying to drive me round the bend, Charlie,’ he said.

‘Who are?’

‘The screws,’ Ronnie said. ‘They keep coming into my room in the middle of the night, waking me up. I know what they’re up to. They’re trying to push me over the edge.’

‘Don’t be silly,’ I said. ‘They wouldn’t do that. Nobody would do that.’

‘That’s what the doctor said when I told him. But I know they are.’

That night, Ronnie put a huge hardback book against the door of his room, thinking that if anyone came in, the book would fall over and wake him, and he would be able to catch whoever they were in the act. Nothing happened that night. Nor the next; nor for the next five nights. The following night around 3 a.m., Ronnie heard a loud bang and jumped out of bed, ready to confront the intruders. But there was no one there. The door was shut, the big book still in place. And it dawned on him that he had been imagining the intruders all the time.

Ronnie always admitted when he was wrong, so, the next morning, he apologized to his doctor, who said: ‘I knew it was all in your mind, because the treatment for the mastoids in your ears meant we had to cut down on your medication, and that caused you to have delusions.’

Why, I wanted to scream, could the doctor not have told Ronnie that before; then he would have known what to expect and would not have got wound up. It seemed the same old story: He’s only Ronnie Kray; it doesn’t matter about him. We don’t have to tell him anything.

Perhaps I should not have been surprised. Throughout Ronnie’s time in Broadmoor, they carried out all sorts of experiments on him, gave him all types of drugs, without once telling him, Reg, or me what they were for or why. I suspected what was going on because I never knew what mood Ronnie would be in from one visit to the next. Ronnie suspected too. He’d say: ‘They do try me out in here, Charlie. They’re always pumping me full of different things. But I take them because they might do me some good.’

That was Ronnie all over. He disliked drugs and hated people talking about them, but he took his medication religiously, because he knew he needed it. He knew that, sometimes, he felt different from other people.

In the main, the Broadmoor staff respected Ronnie and never took liberties with him or wound him up. There was one occasion, however, when a couple of idiots did try to take advantage.

Ronnie had been to an outside hospital for an operation to cure his ear problems. When I visited him in the Broadmoor infirmary, I found him sitting alone in a ward with five other beds. He could barely hear me, but I sensed something was wrong besides the pain.

‘You don’t look too clever,’ I said. ‘What’s the matter?’

‘Two screws in here keep having a go at me,’ he said.

He must have detected a disbelieving look cross my face, because he added, quickly: ‘And this time I’m not imagining it, Charlie. I started eating an orange and they came and took it away. One of them started eating it in front of me and they both stood there laughing.’

He went on to tell me that he had not been allowed a cup of tea since the previous night, and had to go to the toilet for a cigarette when everyone else was allowed to smoke in the wards.

When I confronted the two young male nurses, they laughed in my face.

‘I don’t find your attitude funny,’ I said. ‘Do you realize that my brother has just had a serious operation and you can’t even give him a cup of tea?’

One said the tea was their business, not mine. Then they started laughing again. I freaked.

‘I want to see your guv’nor,’ I snapped. ‘Go and get him. Now. And don’t laugh at me or my brother any more, because I’ll give you both a good hiding.’

That wiped the smiles off their faces. They went off and came back, minutes later, with two of their superiors, who knew me. They expressed their surprise at seeing me so agitated.

‘I think I’m entitled to be when I have these two idiots standing in front of me laughing when I’m trying to get some decent treatment for my brother,’ I said.

I poured out my fury, even threatening to tell the papers and get all our friends to parade outside the hospital with protest banners.

Ronnie was sitting in his bed, saying nothing; he did not want any trouble. But after a while, sick as he was, he couldn’t stand it any longer. What should have been a calm visit was ruined. ‘Don’t worry, Charlie – leave it out,’ he shouted. ‘You’d better go.’

He was right: me making a scene was only going to wind him up and that’s the last thing he needed after what he’d been through. So, reluctantly, I left, warning the hospital bosses that if they antagonized Ronnie and he got violent, I would hold them responsible.

I went back early the next morning to find Ronnie all smiles.

‘After you left yesterday, everything changed,’ he said. ‘They took those two slags off the ward and replaced them,’ he said. ‘I got a cup of tea immediately.’

‘Good,’ I said. ‘That’s how it should be. I can’t understand why they can’t treat you like any other person, and not make a big deal out of it all the time.’

I meant it. He had just come round after an operation and was not well. He did not want to cause any problems and was not going to. Yet two idiots, who were not physically capable of standing up to him, decided to take a liberty just because he was vulnerable. Thankfully Ronnie was sedated and responsible for his actions, so all was calm. But what would have happened if he hadn’t been and was provoked into hitting out at those insolent, unprofessional nurses? No doubt, he, not them, would have got the blame.

In the summer of 1992, Ronnie was pleased when Kate told him she had been asked to write a book about her life as a Kray. He was working with a ghost-writer on a book himself, My Story, but that was concerned mainly with the past. What Kate had to say would be about the present, and Ronnie liked the idea of the public being told what he was like now by someone who spent a lot of time with him.

The offer to Kate was made by John Blake, a tabloid pop reporter who had started a publishing company with his brother’s money, after being sacked from a newspaper. The book he had in mind would make more money from newspaper serialization than over-the-counter sales, but Kate did not mind: it gave her licence to say anything about the twins–and me – whether it was true or not. Much to our dismay, she took full advantage of it.

Over the new few months, Kate asked Ronnie if he wanted to read what she was telling her ghost-writer–a woman named Mandy Bruce–but Ronnie said no; he had no worries. Why should he? He had always treated Kate as a lady; he was certain she would have only good things to say about him, the family in general, and our friends.

How wrong he was. The following year, when he learned what had been written, he was so upset he became emotionally unstable and his paranoia returned. What did not help was that the ghost-writer working on My Story–a TV presenter named Fred Dinenage–misinterpreted certain points, leaving Ronnie desperately unhappy at the finished product.

A warning of the emotional turmoil that would affect Ronnie’s mental and physical state drastically came that summer when doctors reduced his medication level–as another experiment presumably–and he attacked another inmate, Lee Kiernender. I never got to the bottom of what happened exactly, but apparently, Lee irritated him so much one day that Ronnie grabbed him by the throat and tried to strangle him. Feeling Lee’s body go limp in his arms, Ronnie was convinced he had killed him and he was filled with remorse.

He poured out his sorrow to Charlie Smith, vowing that he would never carry out any act of violence again. All he wanted now was peace and quiet.

This was the frame of mind Ronnie was in when he received a hardback of the Sidgwick & Jackson book, My Story. After reading it he hit the roof, claiming that Dinenage had attributed certain things to him that he never said and were not true anyway. Stressed out, Ronnie asked me to go to Broadmoor and, in a highly emotional visit, he told me he was going to ask Robin McGibbon, a journalist and mutual friend, to set the record straight by writing a story for a national newspaper, denouncing the book.

What followed is, I believe, an indictment of Broadmoor for the cavalier manner in which they treated my brother. In just fourteen days, Ronnie wrote sixteen letters to Robin–letters that bore all the hallmarks of a deeply disturbed man suffering a mental breakdown. All inmates’ letters are censored, so why, I’d like to know, did someone not pick up that Ronnie was going through an emotional wringer and needed help?

The first letter, on 11 September, said: ‘Can you put in the papers that the book, My Story, that has just come out is a lot of lies that Reg never said, nor did I. One has only to use their common sense to know we would not put all the lies and rubbish in it.’

Ronnie’s mind was in such turmoil that he wrote another letter the same day, repeating his request. Three days later he wrote two more, saying the same thing. In the second of those letters, Ronnie showed his paranoia by saying all letters should be sent by registered mail, because he was not receiving all the letters he felt he should.

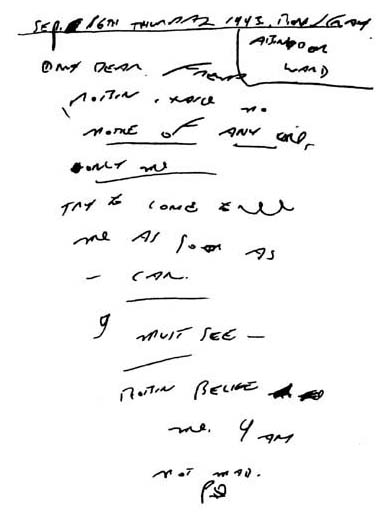

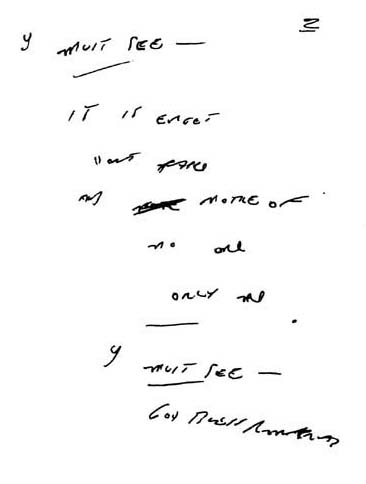

By 16 September, he had got worse. Robin rang me, very worried, saying Ronnie had written the most poignant cry for help: ‘Take no notice of anyone, only me. Try to come to see me as soon as you can. I must see you, Robin. Believe me, I’m not mad. I must see you–it’s urgent. Take no notice of no one only me. I must see you.’

Robin had tried to arrange a visit, but was told that the number of people on Ronnie’s visiting list was so high that it was being cut to ten: the hospital would be in touch to say if Robin could be one of them.

That night, I tried to put Ronnie’s anger and frustration out of my mind as I took Judy to see an old flame of mine, Barbara Windsor, in the famous Joe Orton play, Entertaining Mister Sloane, at the Ashcroft Theatre in Croydon.

When we went backstage afterwards, I sprang a surprise, which backfired on me, giving us all a giggle. After giving Barbara a hug and a peck, I pulled up my jacket sleeve and showed off some gold cuff-links I knew Barbara had bought me during our affair more than thirty years before.

‘Bet you can’t remember these, Barbara,’ I said.

She took one look, then gave me one of those famous cheeky looks. ‘Remember them, Charl!’ she screeched. ‘How can I forget? I bought those cuff-links after you told me you loved me so much you were leaving your wife for me.’

We both roared.

The following week, Ronnie was in an even worse state: he had received a copy of Kate’s book, Murder, Madness and Marriage, and had gone off the dial. She had written certain things he felt embarrassed and humiliated him, and he wanted me to go to Broadmoor immediately to discuss what we should do about it.

I bought a copy of the book and could see why Ronnie was upset. I was shocked at basic inaccuracies that not only Kate but the ghost-writer and publisher had allowed through, but it was Kate’s vitriolic personal attack on me and brazen admission of her infidelity that stung most.

In a chapter, ambiguously titled ‘Friend or Foe?’, Kate says Ronnie was so angry about what I wrote about him in another book that he had disowned me.

She said that ‘…no one could believe that Charlie had been so disrespectful and so disloyal to his own brother.’

And she claimed that Ronnie said: ‘I never want to see Charlie again and I’ll never forgive him. He’s no longer my brother. I don’t have two brothers any more. Just Reggie.’

If I had not been so angry at the stupidity of the woman, I’d have laughed. If Ronnie felt so bad and never wanted to see me again, why was I the first person he turned to in his fury over her book? And why was I on my way to Broadmoor to talk to him about it? Perhaps I shouldn’t have been surprised: Kate had even got the title of my book wrong. It is Doing The Business, but she called it: We Did The Business. As she gets the little, but very important, things wrong, her so-called revelations lose their credibility.

Kate claims I betrayed Ronnie by stating that he was once intimidated by Mafia bosses and frightened for the first time in his life. The truth of the matter, quite simply, is that this remark was wrongly attributed to me–and Ronnie knew that. The real issue, however, is not what I did or did not say–it is Kate’s appalling hypocrisy in accusing me of betrayal when she herself was guilty of treachery on a far grander scale.

She knew–as, indeed, all of us close to Ronnie knew –that he did not expect her to live the life of a nun: she was a youngish, reasonably good-looking woman, with a bubbly personality, and Ronnie understood that a certain type of man might want to get her into bed. He told her she had his blessing to go out and enjoy herself, within reason, as long as she never flaunted whatever sexual encounter she had. This was terribly important to Ronnie: although he was locked away, his pride and self-respect were very much intact and the worst that anyone could do was embarrass him–or mug him off, as they say down the Mile End Road. Kate was fully aware of this: indeed, she admits that Ronnie told her, ‘If you do have a relationship don’t flaunt it.’

Well, sadly, Kate showed her true colours in her book. She did not merely flaunt one of her sexual relationships and mug Ronnie off–she humiliated him. In a tacky chapter, ‘Sex And All That’, she made me squirm as she devoted nearly 4,000 words, over eleven pages, describing her lust for a tall, half-Spanish car dealer she called Pa, and what they got up to when they saw each other several times a week over more man two years.

Ronnie knew Kate was seeing this guy: she had shown him a photograph and he nicknamed him ‘gypsy boy’. What Ronnie did not know was that Kate saw the relationship as far more than merely a sexual fling; she viewed it as some predestined romance that was written in the stars. As she writes: ‘With Pa it was different. Sometimes in life I’m sure you’re fated to be with someone and that’s how it was with me and Pa.’ Can you imagine how Ronnie felt reading that? This was his wife gushing, not about some fancy-free bachelor who had swept her off her feet, but a married man–with a wife and child!

By exposing herself as some sex-starved bimbo with little regard for anything but her own sexual gratification, Kate ridiculed not only Ronnie but herself. How many other prisoners’ wives, I wonder, would have had the gall to talk publicly, and in colourful detail, about adulterous trysts in out-of-the-way restaurants and sexual romps in hotels? Kate seemed positively proud and unconcerned about the effect it would have on Ronnie.

I could hardly believe it when I read: ‘We didn’t rush into bed with each other. We wanted it to be special…we booked into a hotel in Brighton…but didn’t pounce on each other, we wanted to save it. We didn’t want it all over in a few minutes…I was excited. Everything in me wanted this man, Pa picked me up his arms and laid me on the bed…then, very slowly, he undressed me and we made love all night. The next morning I felt great…I would have been happy to stay in that bed for a week…’

What was it Ronnie had told her? Don’t flaunt your relationships. Kate was not merely flaunting, she was revelling in it, gloating almost, in every sexy memory. And to make matters worse, she was happy to see the more salacious bits of her book serialized in a national tabloid newspaper.

Kate rubbed Ronnie’s nose further into it by revealing she went to California on holiday with lover-boy and took him to a marriage guidance counsellor to try to cure his jealousy. But it was Kate’s graphic description of her own appalling, maniacal behaviour in the middle of a busy street that caused Ronnie to flip.

According to her book, Pa was drunk, and infuriated her by breaking a pair of sunglasses and chucking them out of the car Kate was driving. She screeched to a halt, went round to the passenger side, opened the door, then kicked Pa in the face. He got out, forced her against a van, and she stabbed him with her car keys. She drove off, but was so angry she turned round and drove into him as he walked up a hill. Apparently, that was not enough, because she turned round and drove into him again.

‘Then I went really mad,’ she writes. ‘There was a wooden stake lying by the side of the road. I picked it up and began to beat him…I’m not a violent person, but something in me snapped. By now, the police had arrived and they pulled me off him. Good job, too. I think I could have killed him…’

Kate says she was arrested and taken to a police station. But she gave a false name because she did not want Ronnie to hear about it. ‘He would have been livid at me for making such an exhibition of myself,’ she says.

Oh, really! If she was worried about upsetting my brother, Kate could easily have kept quiet about that degrading episode and neither Ronnie, nor anyone else, would ever have known about it. As it was, she wrote about it in detail for book buyers and millions of newspaper readers to see.

Not surprisingly, Ronnie had made his own mind up what to do about a woman he now viewed as a tart.

‘I knew I was right–the girl’s a wrong ‘un,’ he said, as soon as we’d sat down in Broadmoor’s visiting hall that afternoon in September 1993. ‘I’m divorcing her.’

I just sat there, saying nothing, just trying to keep the smile off my face. Ronnie had been stewing on what was in the book and wanted to get it all off his chest.

‘She’s taken a right liberty. I’m in here and she’s out there and I told her I was happy for her to go out and enjoy herself. But she’s showed me up and made me an idiot–a laughing stock.’

What bothered him most was not getting rid of Kate, but what she would say if she saw any pound signs.

‘She’s the type of girl who’ll tell more lies if there’s money in it,’ Ronnie said. ‘She doesn’t care. God knows what she’s going to say next.’

He said he was writing again to Robin and, the next day, another letter went off, pleading: ‘Can you ring my doctor to arrange to see me. Unless Kate stops her book that is diabolical I’m going to divorce her.’

Robin rang me to say that, at last, he had been given a date to visit Ronnie–the following Friday 29 September. But, two days before, he received another letter–the seventh in just two weeks–that was extremely worrying. Ronnie’s paranoia was such that he genuinely believed someone at the hospital did not want the visit to go ahead and was planning to sabotage it.

The letter said: ‘If anyone rings you and says I’ve cancelled the visit, believe it only if it is Stephanie…’ (Stephanie King is a Nottingham housewife, who was acting as a sort of unpaid secretary to the twins.)

In the event, the visit never happened because, the very day Ronnie’s letter arrived, he was taken to Wexham Park Hospital, in Slough, suffering from what was thought to be a mild heart attack. He was still anxious to put right the two books, however, because he wrote to Robin again: ‘I am in hospital. Can you come to see me next Wednesday morning. I may have angina.’

The next day, Ronnie wrote yet again, and this time the plea was desperate: ‘Can you come to see me any day, any time…’

Ronnie was taken back to Broadmoor on the Saturday and insisted on seeing Robin the next afternoon. Robin got a shock when he saw Ronnie. He was normally immaculate in a pressed suit and tie, but this day he was wearing ill-fitting jeans, a rumpled green and mauve rugby-type shirt. He apologized for being scruffy, saying his best clothes hadn’t been sent over from the special care unit, where he had been sent after attacking Kiernender.

When Robin phoned me, my first question was: ‘What about Ronnie’s heart attack?’

‘The doctors told him his heart is okay–very strong in fact,’ Robin said. ‘Apparently, Ron had all the symptoms of a heart attack, but it wasn’t. He hasn’t even got angina.’

‘What’s his mood now?’ I wanted to know.

‘He’s very positive. He’s always bounced back when his health has gone down, and he says he’ll bounce back this time. But he told me the thought of death did occur to him when he collapsed. He said he felt terrible.’

‘Was he scared?’

‘He said he’d never been scared of dying because he believed in reincarnation and often dreamed of who he was going to be in future lives.’

Something that was bothering Ronnie, however, was a rumour that he was so depressed he had lost the will to live. That was rubbish, Robin said; although Ronnie was bored stiff at the moment, he said he still found life interesting and always managed to enjoy himself.

Ronnie was at pains to stress he was not going ‘all nutty and religious’, but he was convinced God had saved his life in hospital.

‘How come?’ I asked.

Robin said: ‘All Ron said was that God performs miracles–like a baby coming out of the womb, and a caterpillar changing into a butterfly– so who is to say God didn’t perform a miracle and deem he should recover?’

I had to smile; that was a side of Ronnie the public did not know. All the tabloids ever talked about was the evil gangland killer with a thirst for violence.

‘What does he want you to do about Kate?’ I asked.

‘Make it public that he was divorcing her because of the way she had embarrassed and humiliated him,’ Robin said. ‘And to make it clear that he is a humble man, with principles, not the flash, arrogant, rude, ignorant idiot she’s made him out to be.’

I could understand Ronnie’s anger. Contrary to what many thought, he was very considerate about other people and their feelings. And he did care about what people thought of him. In his eyes, Kate had betrayed his trust and made a fool out of him. The marriage had been going downhill and her tatty, downmarket book, with its even tattier content, was the last straw.

He was definite he wanted nothing more to do with Kate and asked Robin to tell Stephen Gold, the family solicitor, to start divorce proceedings immediately. I was euphoric. I had reached a point where I couldn’t stand Kate. I’d thought she was genuine and she had turned out phoney. I’d thought she was good for Ronnie, and she had turned out bad. Like Ronnie, I wanted nothing more to do with her.

The mistake Kate made was thinking she could manipulate Ronnie into shoving Reg and me aside so that she would have him all to herself. She believed she was clever, one step ahead, but she was stupid to think that. Blood, as they say, is thicker than water and in times of crisis a family sticks together, no matter what rows they may have had. Ronnie was incensed about her behaviour, but he was beside himself with rage that she had belittled me in such a cruel, unjust manner.

During the marriage, our friends were nice to Kate, but she has lost the respect of everyone. No one has any time for her.

She revelled in being Kray, basked in the limelight the name gave her, and spoke, seemingly with authority, about the family in general. But, really, she knows nothing about us.

I often think what our dear mum would have made of her and her avaricious ways, but Kate was not the sort of girl you take home to mother. She wouldn’t have been mum’s cup of tea, in any situation, but as a daughter-in-law–forget it. As for the old man, he had a very strict Victorian outlook and he would have gone spare at the damaging drivel Kate was allowed to get published.

As anyone who has met me knows, I’m an easy-going guy who tries to be friendly and respectful to everyone. But I have to admit I would find it hard to have anything pleasant to say to my brother’s ex-wife should I be unlucky enough to set eyes on her.

As 1993 drew to a close, I had little time to dwell on Ronnie’s troubled mind; my own emotional and financial crises were building up. Some business deals I’d been counting on had broken down and I was strapped for cash. To make matters worse, Diana could not tolerate our domestic situation any longer and was making it clear she wanted me out of the flat and her life so that she could make a fresh start.

Things came to a head in December when we had a blazing row and she insisted I left. I told Judy and asked if I could move in with her. She would never have been the first to suggest it, but she wanted me under the same roof and readily agreed. Like me, she felt a sense of relief now that the move had been forced on us.

Those first days in Limpsfield Road, being part of Judy’s family, were very strange. I didn’t know what to talk to her children about, but I wanted them to accept me into their home so much that, whenever I went out, I would come back armed with all kinds of sweets, chocolates and Cokes. When Judy came home and we sat down on our own to watch me telly, I would start chatting non-stop. It was a sort of nervousness, I suppose, and, finally, it got up Judy’s nose.

‘For goodness’ sake, Charlie,’ she said one night. ‘Stop talking so much. You don’t have to talk all the time. Relax.’

It gave her the opportunity to get something else off her chest, too. ‘Charlie,’ she said, gently but firmly, ‘something else you don’t have to do, and what I don’t want you to do, is spoil the kids. I don’t want you buying them everything they want all the time.’

I saw her point immediately. The relationship was very important to both of us and she felt it essential to lay down certain ground rules to prevent problems arising later between us. Having just got out of an unhappy marriage, she did not want to waste time on another relationship if it was not going to work. And I felt the same, for different reasons.

Two of those ground rules were (a) that we would both be faithful to each other and I would never lie to her; and (b) that the children’s discipline was Judy’s responsibility, unless their behaviour directly affected me, in which case I would be expected to reprimand them.

It was a calm, clear-the-air discussion that made us both feel better. And, after a lovely, relaxing stay-at-home Christmas with the kids, Judy and I celebrated the arrival of 1994 with optimism for our future together.

I did not feel good about the way I had handled things with Diana. All I could hope was that time would heal the hurt and bitterness she felt at my betrayal.