A FIVE-YEAR-OLD in 1968 paints a picture. What’s in it? First, a mother, giver of paper and paints, saying, Make me something beautiful. Then a house with a door floating in the air, and a chimney with curls of spiraling smoke. Then four Appich children in descending order like measuring cups, down to the smallest, Adam. Off to the side, because Adam can’t figure out how to put them behind the house, are four trees: Leigh’s elm, Jean’s ash, Emmett’s ironwood, and Adam’s maple, each made from identical green puffballs.

“Where’s Daddy?” his mother asks.

Adam sulks, but inserts the man. He paints his father holding this very drawing in his stick hands, laughing and saying, What are these—trees? Look outside! Is that what a tree looks like?

The artist, born scrupulous, adds the cat. Then the horned toad Emmett keeps in the basement, where the climate is better for reptiles. Then the snails under the flowerpot and the moth hatched from a cocoon spun by another creature altogether. Then helicopter seeds from Adam’s maple and the strange rock from the alley that might be a meteorite even if Leigh calls it a cinder. And dozens of other things, living or nearly so, until nothing more will fit on the newsprint page.

He gives his mother the finished picture. She hugs Adam to her, even in front of the Grahams from across the street, who are over for drinks. The painting doesn’t show this, but his mother only ever hugs him when her whistle is wet. Adam fights her embrace to save the painting from getting crushed. Even as an infant, he hated being held. Every hug is a small, soft jail.

The Grahams laugh as the boy speeds off. From the landing, halfway up the stairs, Adam hears his mother whisper, “He’s a little socially retarded. The school nurse says to keep an eye.”

The word, he thinks, means special, possibly superpowered. Something other people must be careful around. Safe in the boys’ room at the top of the house, he asks Emmett, who’s eight—almost grown—“What’s retarded?”

“It means you’re a retard.”

“What’s that?”

“Not regular people.”

And that’s okay, to Adam. There’s something wrong with regular people. They’re far from being the best creatures in the world.

The painting still clings to the fridge months later, when his father huddles up the four kids after dinner. They pile into the shag-carpeted den filled with T-ball trophies, handmade ashtrays, and mounds of macaroni sculpture. They spread on the floor around their father, who hunches over The Pocket Guide to Trees. “We need to find you all a little sibling.”

“What’s a sibling?” Adam whispers to Emmett.

“It’s a small tree. Kind of reddish.”

Leigh snorts. “That’s a sapling, pinhead. A sibling’s a baby.”

“Butt sniff,” Emmett replies. The image is so richly animalistic that Adam will carry it with him into the corridors of middle age. That moment of bickering will make up a good share of everything he’ll recall of his sister Leigh.

Their father hushes the brawl and puts forward the candidates. There is tulip tree, fast-growing and long-lived, with showy flowers. There’s small, thin river birch, with peeling bark that you can use to make canoes. Hemlock forms big spires and fills up with small cones. Plus, it stays green, even under snow.

Jean asks, “Why?”

“Do I have to give my reasons?”

“Canoes,” Emmett says. “Why are we even voting?”

Adam’s face reddens until his freckles almost vanish. Near tears, in the press of impossible responsibility, trying to save others from terrible mistakes, he cries out, “What if we’re wrong?”

Their father keeps flipping through the book. “What do you mean?”

Jean answers. She has interpreted for her little brother since before he could speak. “He means, what if it’s not the right kind of tree for the sibling?”

Their father swats at the nuisance idea. “We just have to pick a nice one.”

Teary Adam isn’t buying. “No, Dad. Leigh is droopy, like her elm. Jean is straight and good. Emmett’s ironwood—look at him! And my maple turns red, like me.”

“You’re only saying that because you already know which tree is whose.”

Adam will preach the point to undergrad psych majors, when he’s even older than his father is on the night they pick a tree for unborn Charles. He’ll build a career on that theme: cuing, priming, framing, confirmation bias, and the conflation of correlation with causality—all these faults, built into the brain of the most problematic of large mammals.

“No, Daddy. We have to pick right. We can’t just choose.”

Jean pets his hair. “Don’t worry, Dammie.” Ash is a noble shade tree, full of cures and tonics. Its branches swoop like a candelabra. But its wood burns when still green.

“Canoes, already,” Emmett shouts. Ironwood will break your ax before you bring it down.

As usual, their father has rigged the election. “There’s a sale on black walnut,” he says, and democracy is over. By chance, nothing in the American arboretum could better suit what baby Charles will grow into: a towering, straight-grained thing whose nuts are so hard you have to smash them with a hammer. A tree that poisons the ground beneath itself so nothing else can grow. But wood so fine that thieves poach it.

The tree arrives before the baby. Adam’s father, cursing and blaming, wrestles the burlap-wrapped root ball toward a hole torn out of the lawn’s perfect green. Adam, lined up with his siblings on the edge of the hole, sees something terribly wrong. He can’t believe no one intervenes.

“Dad, stop! That cloth. The tree is choking. Its roots can’t breathe.”

His father grunts and wrestles on. Adam pitches himself into the hole to prevent the murder. The full weight of the root ball comes down on his stick legs and he screams. His father yells the deadliest word of all. He yanks Adam by one arm out of his live burial and hauls the boy across the lawn, depositing him on the front porch. There the boy lies facedown on the concrete, howling, not for his pain, but for the unforgivable crime inflicted on his brother-to-be’s tree.

Charles comes home from the hospital, a heavy helplessness wrapped in a blanket. Adam waits, month by month, for the choked black walnut to die and take his baby brother with it, smothered in his own clown-covered coverlet. But both live, which only proves to Adam that life is trying to say something no one hears.

FOUR SPRINGS LATER, with the leaves’ first flush, the Appich kids fight over whose tree is the most beautiful. They fight again when the seeds come out, and later the nuts, and finally the autumn rush of color. Health and power, size and beauty: they fight over everything. Each child’s tree has its own excellence: the ash’s diamond-shaped bark, the walnut’s long compound leaves, the maple’s shower of helicopters, the vase-like spread of the elm, the ironwood’s fluted muscle.

Nine now, Adam decides to hold an election. He cuts a slit in the top of an egg carton to make a secret-ballot box. Five ballots, five trees. Each child votes for their own. They have a runoff. Emmett buys four-year-old Charles’s vote for half a Butterfinger, and Jean changes her vote to Adam’s maple out of what can only be called love. It comes down to ironwood versus maple. Campaigning is ruthless. Jean helps Adam make pamphlets. Leigh takes over as Emmett’s manager. For a slogan, Leigh and Emmett doctor a poem they find scribbled in their father’s old high school yearbook:

Don’t worry if your job is small

and your rewards are few.

Even the mighty Ironwood

was once a nut, like you.

To counter, Adam has Jean make a poster reading:

Come on, Sugar, Vote for Maple.

Up in Canada it’s a staple.

“I don’t know, Dammie.” Jean, three years older, has her finger more squarely on the pulse of the electorate. “They might not get it.”

“It’s funny. People like funny.”

They lose the election, three to two. Adam sulks for the next two months.

BY TEN, Adam travels mostly alone. Kids have it out for him. His brother takes him on a hike, then gives him a canteen full of urine on ice to drink. In the park, his friends tell him his scalp is turning green from eating too many potato chips. He rushes home to a mother who chides him for being so gullible. He can’t figure out why people do what they do. His cluelessness only makes others keener to dupe him.

He keeps to himself, but even the subdivision’s barest lot is home to millions of creatures. The Golden Guide to Insects and a jar with a punched lid turns the loneliest Sunday afternoon into a collector’s dream. Armed with The Golden Guide to Fossils, he concludes that the bumps and nubs in the front flagstones are the teeth of ichthyosaurs who went extinct long before mammals were anything but a sideshow on the forest floor. The Golden Guide to Pond Life, The Golden Guide to Stars, to Rocks and Minerals, to Reptiles and Amphibians: humans are almost beside the point.

Months pass in amassing specimens. Owl pellets and oriole nests. The shed skin of a corn snake, complete with tail tip and eye caps. Fool’s gold, smoky quartz, silver-gray mica that flakes like sheets of paper, and a shard of flint he’s sure is a Paleolithic arrowhead. He dates each find and tags it with a location. The collection takes over the boys’ room and spills down the hallway into the den. Even the sacred living room breaks out in exhibits.

He comes home from school late one winter afternoon to find the entire museum in the incinerator. He flies through the rooms, wailing.

“Honey,” his mother explains, “it was all junk. Moldy, bug-infested junk.”

He slaps her. She stumbles back from the sting, hands to her face, staring at the boy. She can’t believe the evidence of her pain. She doesn’t understand what has happened to her son, the one who, at age six, once took a damp dish towel from her hands and told her he’d take over from here.

Adam’s father learns of the slap that evening. He teaches the boy a lesson that involves twisting his wrist until it fractures. No one realizes the wrist is broken until late that night, when it swells up weird and blue like something out of The Golden Guide to Crustaceans.

The Saturday in late spring when the cast comes off, Adam climbs up into his maple as high as he can and doesn’t come down until dinner. Sun passes through the foliage, turning the air the color of a not-quite-ripe lime. It gives him bitter comfort to gaze over the neighborhood’s roofs and know how much better life is above ground level. The palmate leaves wave in the gentle breeze, a crowd of five-fingered hands. There’s a sound like light rain, the shower of thousands of tiny bud scales. High above his head squirrels gnaw at the massed flowers, sucking out their liquid sap, then scattering the spent reddish yellow bouquets across the ground below. Adam counts fifteen different crawling things, from mealy worms to flattened flecks with legs almost too small to see, circling his dimpled limb in search of sweet wellsprings. Brown- and black-hooded birds dart through, feeding on the rafts of eggs that bugs and butterflies leave all over the branchlets. A woodpecker ducks in and out of a hole it made while grub-fishing the year before. It’s a stunning secret that no one in his family will ever know: there are more lives up here, in his one single maple, than there are people in all of Belleville.

Adam will remember the vigil many years later, from two hundred feet up in a redwood, when he’ll look down on a knot of people no bigger than bugs, a democratic majority of whom want him dead.

WHEN HE’S THIRTEEN, the leaves of his sister Leigh’s elm turn yellow long before autumn. Adam sees the withering first. The other kids have stopped looking. One by one, they’ve drifted out of the neighborhood of green things into the louder, flashier party of other people.

The disease that gets Leigh’s tree has been coming their way for decades. Back when Leonard Appich planted his first child’s tree in a fit of fifties optimism, Dutch elm had already ravaged Boston, New York, Philly, and Elm City, New Haven. But those places were so far away. Science, the man figured, would soon come up with a cure.

The fungus gutted Detroit while the kids were still small. Then Chicago, soon after. The country’s most popular street tree, vases that turned boulevards into great tunnels, was leaving this world. Now the disease comes to the outskirts of Belleville, and Leigh’s tree, too, succumbs. Fourteen-year-old Adam is the only one who mourns. His father curses the expense of taking the thing down. Leigh herself hardly notices. She’s on her way to college—tech theater, at Illinois State.

“Of course you’d pick an elm, Dad. You’ve had it out for me since before I was born.”

Adam salvages a bit of wood from the men who come to grind out the stump. He takes it into the basement, planes it down, and engraves it with his woodburning kit. He finds the words in a book: A tree is a passage between earth and sky. He messes up passage. Earth and sky both come out retarded. But he gives it to Leigh anyway, as a going-away present. She laughs at the gift and hugs him. He finds it after she moves out, in the crates she leaves behind for the Salvation Army.

THAT’S THE AUTUMN—1976—when Adam falls for ants. One September Saturday, he watches them flow across the neighbors’ sidewalk, carrying a spilled Popsicle back to their base. The rust-colored shag carpet stretches for several yards. Ants wind through obstacles, piling over themselves. Their massed deployment matches any human genius. Adam pitches camp in the grass alongside the living foam. Ants on the edge of the saturnalia seethe across his socks and up his skinny shins. They mount at his elbows into the sleeves of his tee. They scout his shorts and tickle his nuts. He doesn’t care. Patterns reveal themselves as he watches, and they’re wild. Nobody’s in charge of the mass mobilization, that much seems clear. Yet they port the sticky food back to the nest in the most coordinated way. Plans in the absence of any planner. Paths in the absence of a surveyor.

He goes home to get his notebook and camera. There, he has a brainstorm. He begs some nail polish off of Jean. His sister has gone foolish with age, lost in the swirl of fashion. But she’ll still do anything for her little brother Dammie. She, too, once loved the Golden Guides. But the humans have her in their grip, and she’ll never get free again.

She gives him five colors, a rainbow running from scarlet to cyan. Back at the site, he begins daubing. A tiny globe of Smokin’ Rose sticks to the abdomen of one of the scavengers. One by one, he brands dozens more ants with the same hue. Several minutes later, he starts in again with Neat Peach. By midmorning, the whole spectrum of polish is in play. Soon, colored daubs reveal a tangled conga line of unreal beauty. The colony possesses something; Adam doesn’t know what to call it. Purpose. Will. A kind of awareness—something so different from human intelligence that intelligence thinks it’s nothing.

Emmett, passing by with rod and bait, finds him lying in the grass, snapping pictures and sketching in his notebook. “The fuck you doin’?”

Adam hedgehogs and keeps working.

“This is your idea of a Saturday? No wonder people don’t get you.”

Adam doesn’t get people. They say things to hide what they mean. They run after pointless trinkets. He keeps his head down and keeps counting.

“Hey! Bug boy! Bug boy—I’m talking to you! Why’re you playing in the dirt?”

It startles Adam to hear the evidence in Emmett’s voice: he frightens his brother. He whispers to his notebook, “Why do you torture fish?”

A foot flicks out and catches Adam’s ribs. “The fuck you talking about? Fish can’t feel things, Shit-for-Brains.”

“You don’t know that. You can’t prove it.”

“You want proof?” Emmett reaches down, tears a handful of grass, and stuffs it in his brother’s mouth. Adam, impassive, spits it out. Emmett walks away, shaking his head in pity, victor in yet another one-sided debate.

Adam studies his living map. After a while, the time-lapse flow of color-coded ants begins to suggest how signals might get passed along without any central signaler calling the shots. He moves the food a little. He scatters the ants. He makes barriers and times the ants’ recovery. When the Popsicle is gone, he puts bits of his lunch in different spots and measures how long it takes for those bits, too, to disappear. The colony is swift and cunning—as cunning at getting what they need as anything human.

The bells of the Episcopal carillon peal their foursquare hymn. Six o’clock—time for all delinquent Appiches to head home for dinner. The day’s yield is twelve scribbled pages, thirty-six time-keyed photos, and half a theory, none of which would earn him a broken yo-yo on the open exchange.

All autumn long, whenever he isn’t in school, mowing lawns, or working at the soft-serve, he studies ants. He plots graphs and draws charts. His respect for the cleverness of ants grows without limit. Flexible behavior in the face of changing conditions: What else can you call it but wicked smart?

At year’s end, he enters the district science fair. Some Observations of Ant Colony Behavior and Intelligence. There are better-looking efforts throughout the hall, and ones where the student’s dad has clearly done all the science. But none of the other entrants has looked at a thing the way he has.

The judges ask, “Who helped you with this?”

“No one,” he says, with maybe too much pride.

“Your parents? Your science teacher? An older brother or sister?”

“My sister gave me the nail polish.”

“Did you get the idea from somebody? Did you copy an experiment that you aren’t citing?”

The thought that such an experiment might already have been carried out crushes him.

“You made all those measurements yourself? And you started four months ago? During vacation?”

His eyes fill with tears. He shrugs.

The judges award him no medal—not even a bronze. They say it’s because he has no bibliography. A bibliography is a required part of the formal report. Adam knows the real reason. They think he stole. They can’t believe a kid worked for months on an original idea, for no reason at all except the pleasure of looking until you see something.

IN SPRING, his sister Leigh goes down to Lauderdale with several girlfriends for spring break. On the second night of vacation, outside a beachfront clam shack, she gets into a red convertible Ford Mustang with a guy she met three hours earlier. No one ever sees her again.

His parents are frantic. They fly down to Florida twice. They scream at law officials and spend lots of money. Months pass. There are no leads. Adam realizes there never will be any. Whoever has taken his sister is shrewd, meticulous, human. Intelligent.

Leonard Appich won’t give up. “You all know Leigh. You know how she is. She’s run away again. We’re not holding any service until we know for sure what happened to her.”

Know for sure. They know. Adam’s mother throws Leigh’s words from the previous spring back in the man’s face. You’ve had it out for me since before I was born. Patterns rise up, and she grabs at them. “You planted an elm for her, when they’d been dying everywhere for years? What were you thinking? You never did like her, did you? And now she’s raped and lying dead in a landfill, and we’ll never know where!”

Lenny breaks her elbow, by accident. In self-defense, he keeps telling anyone who’ll listen. That’s when Adam realizes: Humankind is deeply ill. The species won’t last long. It was an aberrant experiment. Soon the world will be returned to the healthy intelligences, the collective ones. Colonies and hives.

. . .

JEAN TAKES HER BROTHERS into the forest preserve. There, the three of them hold the service their father won’t allow. They build a bonfire and tell stories. Twelve-year-old Leigh, running away from home after Dad slapped her for whispering asshole under her breath. Fourteen-year-old Leigh, punishing them all for hating her by refusing to speak to anyone except in her sophomore Spanish. Eighteen-year-old Leigh, playing Emily Webb, coming back to Earth to relive her twelfth birthday. A brilliant ghost who had the whole high school in tears.

Adam takes the elm plaque he inscribed for his sister and throws it on the fire. A tree is a passage between earth and sky. Elm isn’t a great firewood, but it burns without too much persuasion. All his botched words turn perfect and vanish into the general black—first tree, then passage, then earth, then sky.

The science fair judges cure Adam Appich of any desire to keep a field notebook on anything at all. He outgrows ants. He puts the Golden Guides by the curb. The secret museum treasures hidden from his mother’s vacuum cleaner he now gladly trashes. Childish things.

High school is four dark years in the bunker. He’s not without friends or fun. In fact, there’s a surplus of both. Nights getting smashed and skinny-dipping in the reservoir above town. Entire weekends in basements pitching dice and arguing over esoteric role-playing rules with obese, anemic boy-men who tote suitcases full of collectible trading cards. The game’s monsters are like natural history gone wrong. Giant bugs. Killer trees. The point of the game is to extinguish them all.

“Testosterone,” his father explains. He’s now afraid of the hulking boy, and Adam knows it. “Storms of hormones, and no port in sight.”

Though Adam wants to hurt the man, his father is not wrong. There are girls, but they baffle him. They pretend to be stupid, by way of protective coloration. Passive, still, and cryptic. They say the opposite of what they mean, to test if you can see through them. Which they want. Then resent when you do.

He organizes raids on the neighboring high school, intricate nighttime operations involving miles of toilet paper tossed up in the branches of lindens. The strips dangle for months like giant white flowers. He passes under them on his mountain bike, feeling like a genius guerrilla artist.

He and a friend map the school, the supermarket, the branch bank. They plan what kind of hardware they’d need to make a heist. The plans get elaborate. They price weapons, just for grins. It’s a game for Adam: logistics, planning, resource management. For his friend, it’s one step away from religion. Adam watches the precarious boy, fascinated. A seed that lands upside down in the ground will wheel—root and stem—in great U-turns until it rights itself. But a human child can know it’s pointed wrong and still consider the direction well worth a try.

HE GROWS GOOD at figuring the absolute minimum work required to pass any class. No adult gets anything from him but what he’s required to give. The plummeting report cards baffle his mother. “What’s going on, Adam? You’re better than that!” But her voice is flat and defeated. Jean sees him going down. She scolds, jokes, and pleads. But then she heads to college, in Colorado. There’s no one left to make him answer for himself.

Leigh never comes back. Adam’s father’s search tapers off to nothing. His mother starts nursing quantities of codeine. Soon enough, she’s on a circuit of drugstores across many towns. She stops cooking and cleaning house. Adam’s lifestyle isn’t impacted. He adapts and evolves. Survival of those who survive.

A JOKE OFFER from a friend—Three bucks if you do my algebra—and he finds himself with easy pocket money. So easy, in fact, that he starts to advertise. Assignments completed in any subject except foreign languages, at any desired quality, as fast as you need them. It takes a while to find the right price point, but when he does, the clients fall in line. He experiments with volume discounts and pay-ahead plans. Soon he’s the proprietor of a successful small business. His parents are relieved to see him doing homework again, for hours each night. They love that he stops bugging them for cash. It’s like win-win-win. Morning in America, with the free market doing its thing, and Adam goes to bed each night thankful to have been born into an entrepreneurial culture.

He’s quick and conscientious. Every assignment is ready by deadline. Soon he has built the most reliable and respected cheating franchise at Harding High. The business makes him almost popular. He socks away most of the cash. There’s nothing he can spend it on that gives him more pleasure than looking at the balance accumulating in his passbook savings account and calculating dollars per duped educator.

Demanding work does requires sacrifice, however. He’s forced to learn all kinds of interesting things that shouldn’t interest him.

EARLY IN THE FALL of senior year, Adam’s in the public library cranking out a psychology paper for a classmate who understands the bipedal beast even less than he does. Cite at least two books. Whatever. He rises from his carrel and wanders to the proper spot in the library shelves. Hours of work leave him cross-eyed. In the low library light, the books look like town houses for pipe-cleaner people.

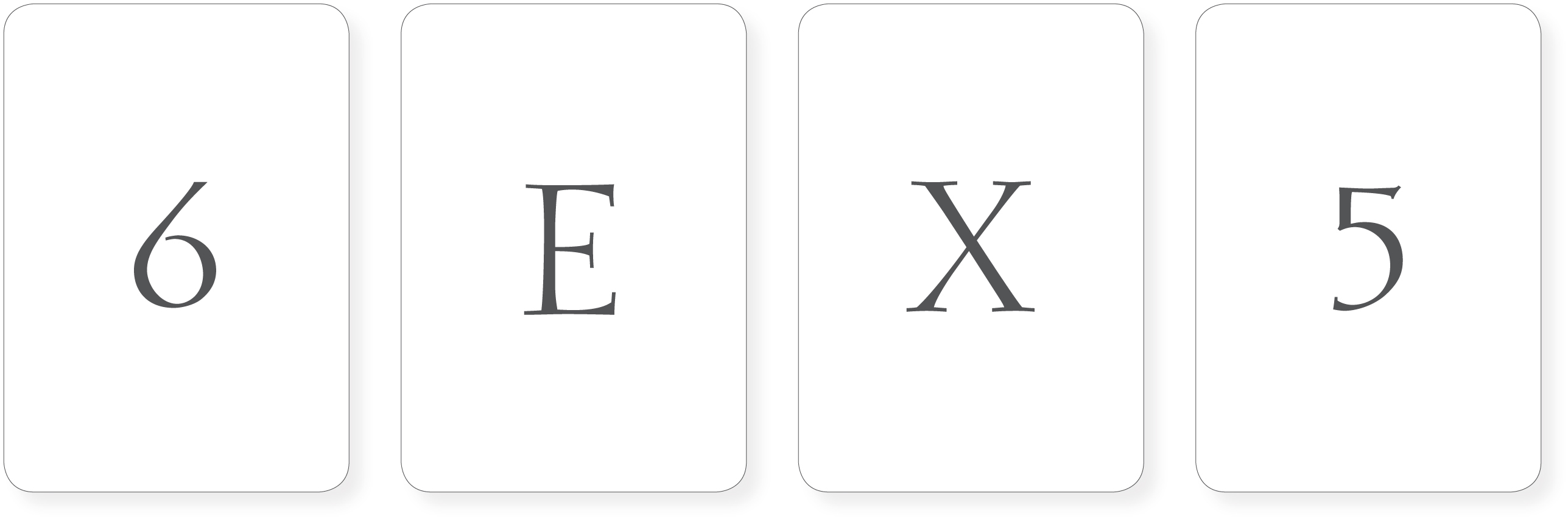

One spine jumps out at him. Its electric lime letters scream out against a black field: The Ape Inside Us, by Rubin M. Rabinowski. Adam pulls down the hefty volume and plops into a nearby armchair. The book falls open to an image of four cards:

Beneath, a caption reads:

Each of these cards has a letter on one side and a number on the other. Suppose someone tells you that if a card has a vowel on one side, then it has an even number on the other. Which card or cards would you need to turn over to see if the person is right?

He perks up. Things with clean, concise, right answers are antidotes to human existence. He solves the puzzle fast, with total confidence. But when he checks his solution, it’s wrong. At first he thinks the printed answer is in error. Then he sees what should have been obvious. He tells himself he’s just wiped out from hours of working on other kids’ assignments. He wasn’t focusing. He would have gotten it, if he’d been paying attention.

He reads on. The book claims that only four percent of typical adults get the problem right.

What’s more, almost three quarters of people who miss the problem, when shown the simple answer, make excuses about why they failed.

He sits in the armchair, explaining to himself why he has just done what almost every other human being also does. Below the first row of cards, there’s another:

Now the caption says:

Each one of these cards stands for a person in a bar. One side shows their age and the other shows their drink. If the legal drinking age is 21, which card or cards do you need to turn over to see if everyone is legal?

The answer is so obvious Adam doesn’t even need to find it. He gets it right this time, along with three-quarters of typical adults. Then he reads the punch line. The two problems are the same. He laughs out loud, drawing looks from the gray-haired, late-night public library crowd. People are an idiot. There’s a big old OUT OF ORDER sign hanging from his species’ pride-and-joy organ.

Adam can’t stop reading. Again and again, the book shows how so-called Homo sapiens fail at even the simplest logic problems. But they’re fast and fantastic at figuring out who’s in and who’s out, who’s up and who’s down, who should be heaped with praise and who must be punished without mercy. Ability to execute simple acts of reason? Feeble. Skill at herding each other? Utterly, endlessly brilliant. Whole new rooms open up in Adam’s brain, ready to be furnished. He looks up from the book to see a library closing down and throwing him out.

At home, he reads on into the night. He picks up again, through breakfast the next morning. He almost misses the bus. He fails to deliver the day’s homework to his clients. It’s the first blow to his good name since he set up the cheating business. He holds The Ape Inside Us under his desk during the first three periods, educating himself on the sly. He finishes before lunch, then starts it all over again.

The book is so elegant that Adam kicks himself for not having seen the truth long before. Humans carry around legacy behaviors and biases, jerry-rigged holdovers from earlier stages of evolution that follow their own obsolete rules. What seem like erratic, irrational choices are, in fact, strategies created long ago for solving other kinds of problems. We’re all trapped in the bodies of sly, social-climbing opportunists shaped to survive the savanna by policing each other.

For days, the book carries him along in a happy stupor. Armed with the patterns the book reveals, he imagines himself running experiments on every girl in school, a dollop of nail polish on their shoe-heels to keep track of their comings and goings. The best part is Chapter 12, “Influence.” Had he read it as a freshman, he’d be school president-for-life. The mere idea that human behavior—his lifelong nemesis—possesses hidden but knowable patterns as beautiful as anything he once witnessed in insects makes his insides sing. He feels lighter and righter than he has since his sister disappeared.

. . .

WHEN THE TIME COMES to take the college entrance exams, he nails them. His analytical skills top out in the ninety-second percentile. In grade-point ranking, however, he barely manages to sneak into slot 212 in a graduating class of 269. No self-respecting college will even consider him.

His father waves him off. “Go to JC for two years. Wipe the slate clean and start again.”

But Adam doesn’t need to wipe the slate. He just needs to show it to someone who can read between the chalky lines. He sits down at the dining room table one Saturday morning before winter break and composes a letter. It feels like entering observations into his boyhood field notebooks. Outside the window are what remain of the children’s trees. He remembers how he once believed in some magic link between the trees and the children they were planted for. How he made himself into a maple—familiar, frank, easy to identify, always ready to bleed sugar, flowering top-down in the first sunny days of spring. He loved that tree, its simplicity. Then people made him into something else. He takes his pen to the top of the page and writes:

Professor R. M. Rabinowski

Department of Psychology

Fortuna College, Fortuna, California

Dear Professor Rabinowski,

Your book changed my life.

He tells a full-fledged conversion narrative: wayward boy saved by a chance encounter with brilliance. He describes how The Ape Inside Us awakened something in him, although the awakening has come, perhaps, too late. He says how he failed to take school seriously until the book fell into his lap, and how he may now have to spend years clearing his record at community college until he gets the chance to study psychology at a serious institution. No matter, he writes. He is in the professor’s debt, and as Rabinowski himself says, on page 231: “Kindness may look for something in return, but that doesn’t make it any less kind.” Perhaps unlooked-for kindness along the way might yet shorten the path ahead.

Outside the window, his maple catches a breeze. Its branches scold him. He’d turn scarlet for shame, if he wasn’t desperate. He forges on, larding the letter with half a dozen techniques picked up from Chapter 12, “Influence.” His words of thanks contain four of the top six releasers for producing action patterns in someone else: reciprocity, scarcity, validation, and appeal to commitment. He hides the evidence of his begging under another trick gleaned from Chapter 12:

If you want a person to help you, convince them that they’ve already helped you beyond saying. People will work hard to protect their legacy.

It stuns his parents but doesn’t entirely shock Adam when a return letter shows up at the house from the author of The Ape Inside Us. Professor Rabinowski writes that Fortuna College is a small, alternative school for unconventional students seeking an intense, questioning approach to education. The admission process places no great store on high school transcripts but looks for other evidence of special motivation. And while he makes no guarantees, Professor Rabinowski promises that Adam’s application will be given serious consideration. Adam need only write the strongest entrance essay that he can.

Clipped to the formal letter is an unsigned index card. In wild and spooky blue-inked scrawl, someone has printed, “Don’t ever blow smoke up my ass again.”