Jean Valjean had been born into a poor peasant family in Brie, a small village not far from Paris. He did not learn to read as a child, and once he became an adult he took a job pruning trees in Faverolles. His father’s name was also Jean Valjean, while his mother’s maiden name was Jeanne Mathieu.

As a child, Jean Valjean had a somber and quiet disposition, which is somewhat typical of children with an affectionate nature. On the whole, however, there was nothing striking about his appearance. He had lost his father and mother at a very young age, losing his mother to what was known at the time as milk fever—not to mention a lack of medical care for her sickness. His father also was a laborer who pruned trees and had fallen to his death from one of those trees.

After his parents’ deaths, the only remaining family member Jean Valjean had was an older sister who raised him. She provided food and lodging for her younger brother as long as her husband had remained alive. Yet his sister was widowed when Valjean was twenty-five years old, at a time when her seven children were from one to eight years of age. Valjean then stepped in, and with the tables now turned, supported his sister who had raised him. He saw this responsibility as his duty, something not uncommon among the peasants of his day.

Valjean spent his younger years in meager, manual labor—always toiling for little pay. And because of the long hours he worked, in order to provide for his sister and her children, he never had the opportunity to find a woman and to fall in love.

During pruning season, he earned only eighteen sous a day. Once that season ended, he would then hire himself out as a reaper, a teamster, or as a common laborer. He took any job he could find, as would his sister, although there was little she could do while caring for seven small children. They were a sad lot, living in misery and facing nothing but their slow demise. And when it seemed nothing could get worse, they encountered a very difficult winter in 1795. Valjean had no work, and the family had no bread. No bread—and seven small children!

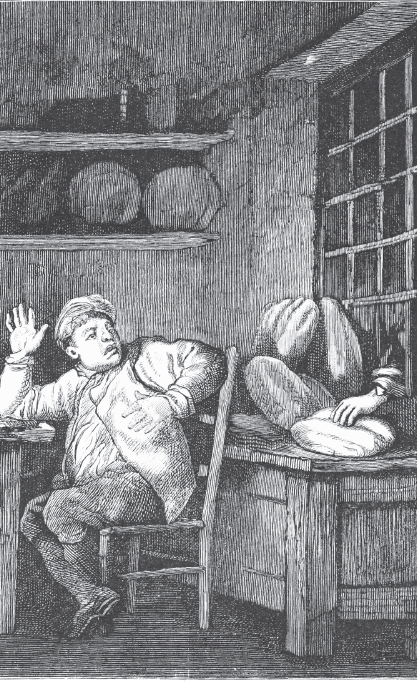

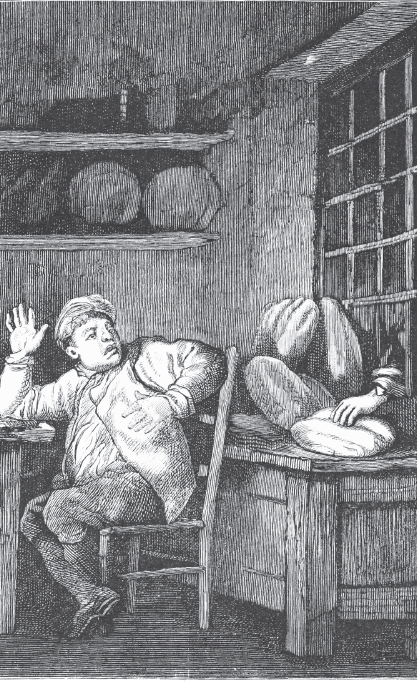

One Sunday evening during this bitter winter, Maubert Isabeau, the baker at the Church Square at Faverolles, was preparing for bed when he heard the sound of glass breaking. The noise seemed to be coming from the front of his shop, and he arrived there just in time to see an arm reaching through the hole in the glass, which apparently had been made by a fist. He saw a hand grab a loaf of bread that then was quickly pulled outside through the window.

At once Isabeau ran outside, as the thief attempted to get away as fast as he could run. Yet the baker continued to pursue him and finally overtook him, forcing him to stop. In the meantime, the thief had thrown the loaf of bread away. However, the evidence of his bleeding arm betrayed him. The thief was Jean Valjean.

Valjean was taken before the court and charged with the breaking and entering of an inhabited house at night, and with theft. The fact that he owned a gun, was well known as an excellent marksman, and previously had been charged with poaching, did not help his case. Therefore, Valjean was found to be guilty by the court, and with the legal codes being very explicit, was condemned to spend the next five years in prison at hard labor.

Jean Valjean steals a loaf of bread.

Valjean often could be seen weeping while imprisoned. His heavy sobbing would impede his speech, but he could be heard to mumble, “I was only a pruner of trees in Faverolles.” Still sobbing, he would raise his right hand and gradually lower it seven times, as though he were patting the seven heads of his dear nieces and nephews. Seeing his apparent love for them, it was easily discerned that his crime had been done for the sake of those poor and hungry children.

Whenever the prison transported him to another place of backbreaking work, he was forced to sit on an open cart with a heavy chain around his neck. In fact, all the things that had once constituted his life were now erased, including his name. He was no longer Jean Valjean, but was prisoner number 24601.

Toward the end of his fourth year in prison, with only one year remaining to serve, Valjean’s first opportunity came to escape. His fellow prisoners assisted him, which was common in such a sad place. He got away, but on the evening of the second day was captured. At this point, he had neither eaten nor slept for thirty-six hours. Upon being taken before the court once again, he was condemned for this new crime to serve an additional three years in prison—now a total of eight years.

During his sixth year in prison, Valjean had his next opportunity to escape. Although he took advantage of the opportunity, he could not fully run away. When he was missing at roll call, the guards fired their cannon as a warning, and finally a night patrol found him nearby, hiding under the keel of a boat under construction. He resisted the guards who seized him, which added rebellion to the charge of escape. The new case against him was punished by an additional five years, two of which were to be served in double chains. Now his sentence amounted to thirteen years in all.

In the tenth year of Valjean’s sentence, another escape opportunity presented itself. Once again he tried to escape but succeeded no better. Three more years were added, now making his sentence sixteen years. Then during his thirteenth year, he made his last escape attempt, only succeeding in being recaptured within four hours. The cost for those four hours was three more years, for his sentence was extended again—now to a full nineteen years.

Finally, in October 1815, he was released. He had entered prison in 1796—serving nineteen years for having broken a pane of glass and for stealing a loaf of bread! Jean Valjean had entered prison weeping, sobbing, and in full despair. He emerged from the prison still totally dejected, but as a man without any show of emotion and with an expressionless face.

When Jean Valjean heard the strange words, “You are free,” the moment seemed amazingly impossible to him. It was as though a strong ray of light from the living suddenly penetrated his entire being. He was overcome by the idea of freedom and liberty, but the bright light within him quickly faded. He had hoped for a wonderful new life yet soon was to discover the only kind of life his yellow passport would provide.

The very day after being freed from prison, Valjean saw some men working in the town of Grasse. They were unloading some bales in front of an orange-flower perfume distillery when he offered his services. Needing more help, the foreman accepted his offer, so he immediately set to work. He was intelligent, strong, and good with his hands, and the foreman seemed pleased with him. While he was at work, a policeman passed by, observed him briefly, and then demanded to see his papers. Valjean produced his yellow passport, which the policeman quickly reviewed and handed back to him. With this done, Valjean resumed his work.

While he labored, he questioned one of the other workmen and was told the daily pay for this work was thirty sous. Yet when evening arrived and he presented himself to the owner of the distillery to be paid, the man handed him only fifteen sous without uttering one word. Valjean protested but was told, “That is enough for you!” And when he persisted in his protest, the owner looked him straight in the eyes and said, “You must beware of the prison.”

Once again Valjean felt that he had been robbed. The state and society had taken everything from him while in prison, including most of the meager savings he had been able to accumulate. Now it was happening to him as a man who supposedly was free.

Valjean’s freedom from prison was not true deliverance. He had been set free from his chains but not from his sentence.