From the beginning to 1916

The origins of the cigarette and trade card can be traced back to the eighteenth century, when it became common for tradesmen to produce cards which contained their business details, with perhaps a logo or pictorial representation of their work. During the twentieth century, the development of recognizable national brands, and advances in colour printing technology, led to a rapid increase in the production of trade cards and they became a popular promotional tool throughout Europe and North America. The Au Bon Marché store in Paris was one of the first shops to develop the idea of a series of cards, aimed at keeping the customer returning to the store in order to complete the set. Over 400 sets of Au Bon Marché cards were issued between 1840 and 1912. The cards were beautifully coloured and featured subjects as diverse as Musical Instruments, Halley’s Comet and In the Year 2000. They also sought to show the pleasure of shopping at the Au Bon Marche storé.

The Liebig Extract of Meat Company, manufacturers of products such Oxo cubes and Fray Bentos pies, issued over 4,000 sets in a range of European languages over the course of nearly a century. When making a purchase from this company, customers could collect coupons from the products they bought and exchange them for a series which would be of interest to them, rather than having to collect the series currently in distribution. In addition, the series were generally limited to between 6 and 12 cards. This meant that customers were more likely to stay loyal to the brand, rather than opting for an alternative if the topic of the current series was of little interest. Their choice of subjects was eclectic to say the least, including Strange Feminine Hair Styles and The Cultivation of Tobacco in Sumatra. The Education in Ancient Greece series was issued in France in 1888. Some collectors devote their entire interest in cartophily to the collection of Liebig cards, such are their attractiveness and variety. In 1971 the company was acquired by Brooke Bond, themselves a significant producer of trade cards in the twentieth century. Despite their beauty and collectability, many original sets of Liebig cards can be bought for a few pounds and therefore a sizeable collection can be formed quickly.

The progression from the general trade card into a cigarette card occurred due to the fragility of early cigarette packets. Commercial production of cigarettes had been started in 1865 by Washington Duke of North Carolina. These were individually hand-rolled and as the craze for smoking them spread, a skilled worker could make 250 cigarettes an hour. It was with the invention of the cigarette-making machine in 1881 that the mass-production of cigarettes, and with them the associated cigarette trade card, really took off, with cigarette companies increasing productions from about 40,000 hand-rolled cigarettes per day to around 4 million by the 1890s.

The cigarettes were sold in a flimsy paper wrapping and were liable to damage before they could be smoked, therefore a thicker piece of card was inserted to stiffen them. James Buchanan Duke, who had taken over the cigarette business from his father, decided to include a colourful advert on these card stiffeners. The first known dateable cigarette card appeared in 1879 and featured the Marquis of Lorne, son-in-law of Queen Victoria (see Chapter 11).

Shortly afterwards, in 1880, a set of four Actresses and a set of four Presidential Candidates were issued. Soon other tobacco manufacturers followed suit, as rival companies sought to appeal to the ever-expanding but highly competitive smoking market. A variety of subjects was chosen to appear on these cards, ones that it was thought would appeal to the male smoker; glamourous actresses, beauties, sports stars and military themes. These one-off cards were quickly developed, as had been the case with Au Bon Marché and Liebig, into themed sets, appealing to people’s desire to collect the complete series.

The cards had to be of sufficient quality, both in terms of the card and the design, to persuade the consumer to complete the set. Therefore they were initially produced to be both visually appealing and informative. Manufacturers then realised that the card’s attraction could be further enhanced by reducing the size of the company logo on the back, and providing a brief description of the subject of the illustration.

These early American cards featured subjects that would become popular themes over the next century: Dogs of the World, Great World Leaders and Flags of All Nations. However, one series that would be considered tasteless and offensive today was Kimball’s 1890 series of Savage and Semi-Barbarous Chiefs and Rulers, a selection of rulers from North America and the Indian subcontinent.

By 1890 almost every American tobacco firm had issued at least one series. They frequently featured pictures of attractive ladies to appeal to the male smoker. These included Actresses and Beauties, Dancing Women, Our Little Beauties and Dancing Girls of the World. In fact, card issuers needed little excuse to feature an attractive-looking female, with Kimball’s Pretty Athletes series of 1890 depicting women demonstrating a variety of sporting pursuits, with the emphasis certainly not on improving people’s understanding of sporting techniques. In addition, sporting and military subjects were popular. American patriotic spirit was encouraged by the Liberty series, featuring events such as the Boston Tea Party and the Battle of Concord.

It was in 1890 that Duke’s company became instrumental in the formation of the American Tobacco Company, an amalgamation of the five largest tobacco firms; in addition to Duke’s the ATC included Allen & Ginter, Goodwin & Company, W.S. Kimball & Company & Kinney Tobacco. By 1901 the ATC had absorbed the business of 250 firms, some of whom continued to trade in name only, but under the auspices of the ATC. Many sets of cards were issued multiple times, under different company names but under the umbrella of the ATC. However, according to I.O. Evans in his Cigarette Cards and How to Collect Them (1937) ‘card collecting had little vogue among American youth...as the cards appeared intermittently, and were often exchangeable, sometimes for albums and sometimes for boxes of sweetmeats.’

It was the Bristol company of W.D. & H.O. Wills which became the first British issuer of cigarette cards. In 1887 they began to print a few lines of wording on the stiffeners included in their packets. By 1890 they had replaced the wording one side with a small picture of their product and by 1894 they were issuing small replicas of eight of their showcards. Early themed issues including Soldiers of the World (100 cards) and the quirky Animals in Fancy Costume (50 cards). In 1895 they produced a series of 25 Ships and in 1896 a set of 50 Cricketers, the latter being one of the most collectable issues today, with a catalogue price of nearly £5,000. By 1901 they had issued series on Soldiers and Sailors, Beauties, Seaside Resorts, Sports of All Nations, Kings and Queens and a second Cricketers set. Other British tobacco manufacturers were quick to copy the idea. These included John Player & Sons of Nottingham, Godfrey Phillips, Lambert & Butler, Cope and Kinnear. Among the early Player’s sets were Castles and Abbeys, A Gallery of Beauty and Actors and Actresses. Like their American counterparts, the British cards were mainly designed to appeal to men, who in those pre-First World War days made up the vast majority of the smoking population. Therefore the subjects contained a high percentage of sporting and military themes, as well as pictures of attractive-looking women.

The patriotic fervour of the Boer War, and the issuing of sets of cards on that theme by British manufacturers, had seen a sharp decline in UK sales for the American Tobacco Company. To reassert their position within the British market, in September 1901 the ATC purchased Ogden’s, a Liverpool-based firm, for over £1,000,000. Ogden’s continued their prolific output of cigarette cards under their new owners and to combat this threat, the thirteen remaining major British manufacturers consolidated to form the Imperial Tobacco Company Ltd in November of the same year. Over £12,000,000 was paid out in compensation to existing shareholders. The war over the British market between the ATC and the ITC was brief, and in 1902 an agreement was signed between them that they would each focus on their domestic markets in the USA and the UK.

Cigarette cards themselves reflected this ‘tobacco war’, with the American-owned Ogden’s issuing cards with the slogan, ‘British made by British Labour’ on them. In riposte, Godfrey Phillips produced a card depicting a Union Flag with the message, ‘They’re English. Quite English You Know’. To grow the tobacco business throughout the rest of the world, a joint British American Tobacco Company Ltd was formed on 29 September 1902, with James B. Duke and William H. Wills at its head.

During this period, newspapers contained no photographs, therefore trade cards offered a window onto the wider world for millions of men, women and children. They carried knowledge and information on an ever-widening range of subjects to millions of people during a time when the school leaving age was only 12 and levels of literacy and general knowledge were much lower than today. As Roy Genders put it in his A Guide to Collecting Trade and Cigarette Cards (1975):

Cigarette smokers everywhere found cards and the subject matter of the greatest interest for they passed away an evening when there was neither radio nor television, and motor cards were only for the wealthy. Encyclopaedias were few and far between and the cards were the only way open to the man-in-the-street to gain knowledge of what was going on around him. Remember, too, that news-papers carried no pictures. The cards were not only a lasting form of advertising to the maker’s good, but were a treasure house of knowledge to those who had no access to higher education and so eagerly were they collected that the cards became an integral part of our lives.

The Boer War of 1899-1902 had served to raise the profile of the cigarette card even further in British life. Wills produced a Transvaal series which eventually ran to 370 different varieties; it reflected the course of the war, with changing maps of the frontiers and promotions and deaths within the army. From that moment, contemporary events became an important feature of cigarette card issues.

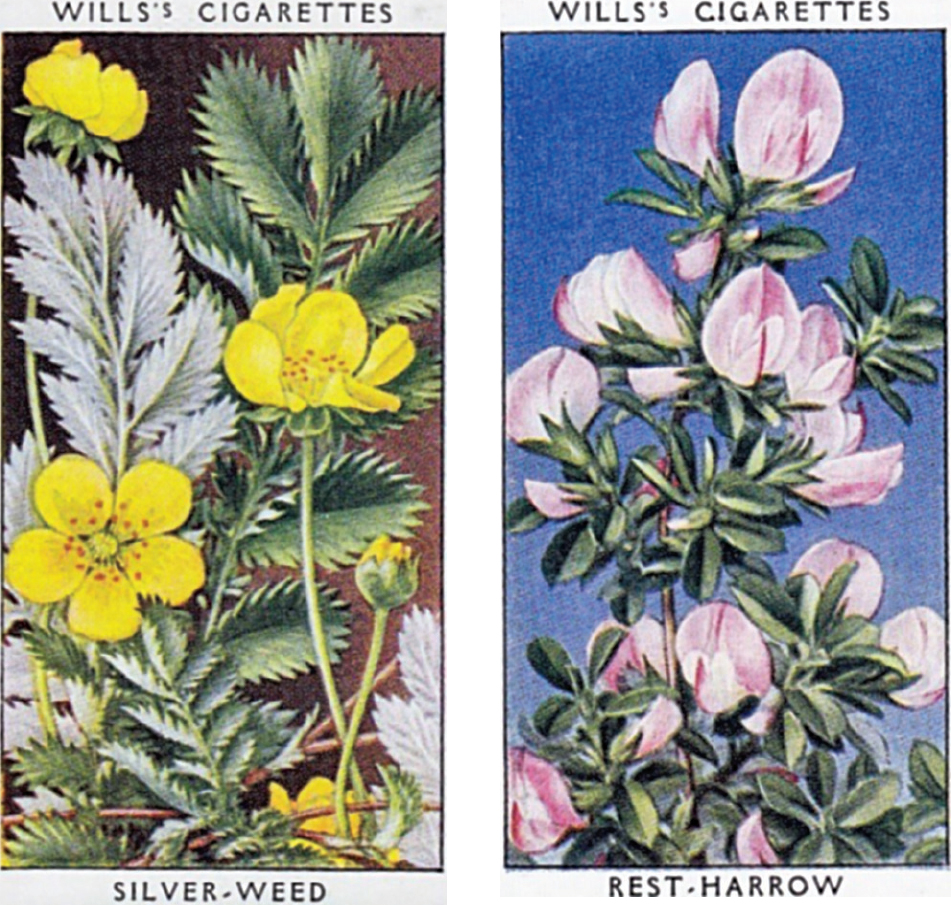

As the first decade of the century progressed, firms began to introduce sets of more topical and general interest. For example, Wills’ issued sets on First Aid, Physical Culture, Fish and Bait and Flowers, while Player’s responded with Wonders of the Deep, Gems of British Scenery and Fishes of the World. Ogden’s also issued sets on varied themes, including the Royal Mail and British Birds. Some of these sets were duplicated by different firms under the Imperial Tobacco umbrella. Military issues continued after the conclusion of the Boer War, with cards depicting regimental uniforms, badges, equipment and personalities.

One particularly unusual noteworthy set of cards from this era is James Taddy’s Clowns and Circus Artistes. Amounting to 20 cards, there are fewer than 20 original sets in existence of this series. A general release had been planned for circa 1915, but the First World War, and the subsequent collapse of the company, meant that they were never issued. The set features clowns, dogs, horses, elephants and other circus acts. When individual cards come up on internet auctions sites, they can realise between £400 and £700. Due to their attractiveness, a reprint was done in 1991, and this reproduction set can be purchased for a few pounds, allowing the collector to appreciate the fine artwork of the original designs for a rather smaller investment.

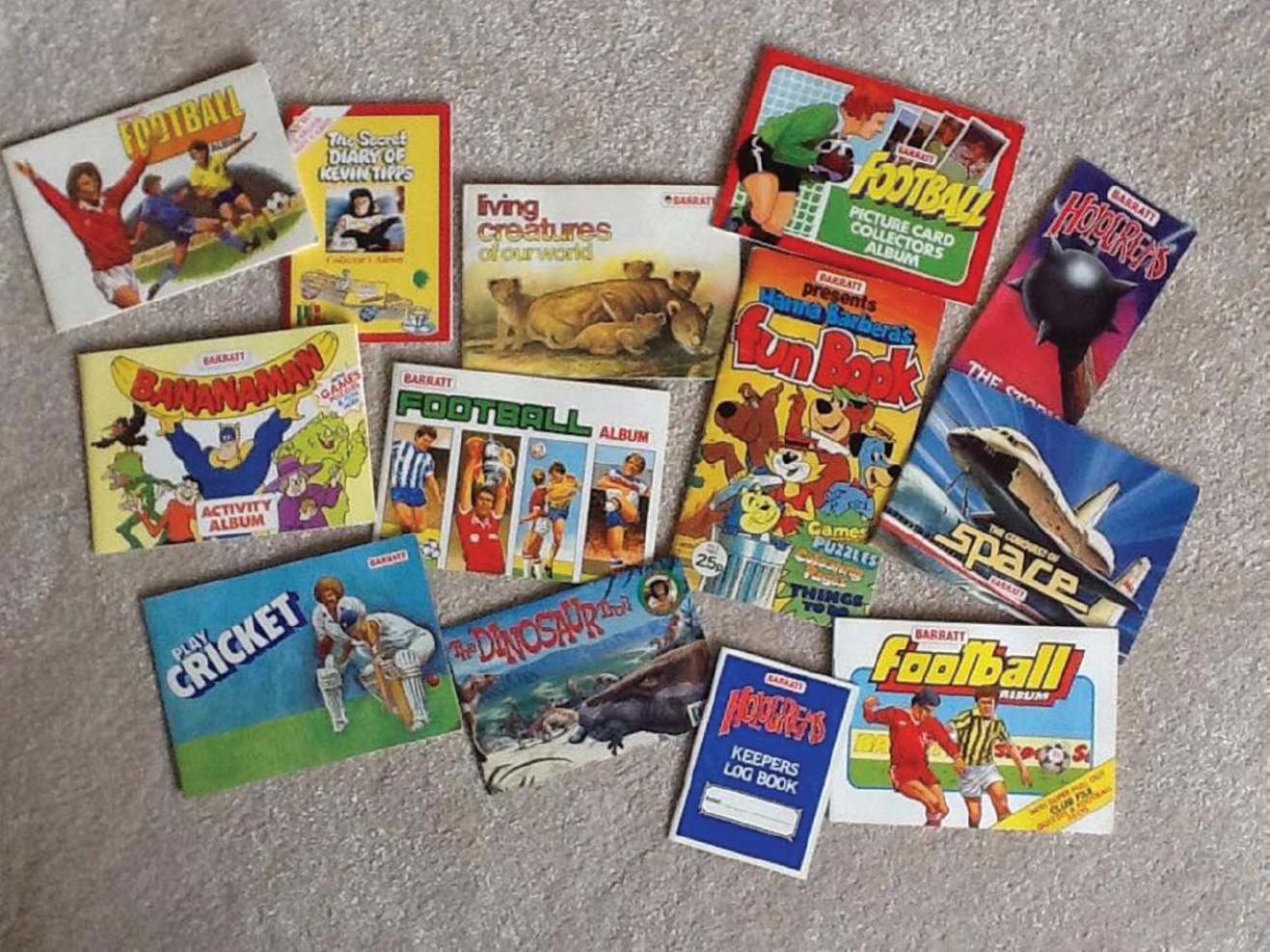

In addition to the growth of the cigarette card phenomenon, other British firms began to expand their issue of trade cards. Many of these were confectioners, such as Barratt & Co, Cadbury, Fry and Maynard. As people did not tend to buy their products in the same quantity as cigarettes, their card series tended to be smaller. For example, Cadbury’s British Colonies, Maps and Industries of 1908 ran to just six cards.

During the First World War, cigarette cards, like many other printed materials in the UK, became subject to censorship. The Times reported on 15 September 1916 that:

The Admiralty and the War Office have decided that on and after September 15 all new pictorial representations, other than official photographs, including picture post-cards and cigarette stiffeners which illustrate subjects of a naval and military nature connected with the war, as also illustrations of aircraft and aeronautical subjects, should be submitted in duplicate to the Press Bureau before publication.

Failure to observe this protocol would render the pictures:

…liable to seizure if considered by the competent naval or military authorities to be susceptible of conveying information of value to the enemy of to be in any way prejudicial to the public safety of the defence of the realm, and the persons concerned are liable to prosecution.

From 1917 through to 1922 the printing of cards was discontinued, as paper was in such great demand for making cartridge cases. Prior to this date, however, the war had already had an impact on the content of cards issued, with an increase in military themes, and with the cancellation by Wills of a set commemorating the centenary of Britain’s victory over France at Waterloo in 1815, to be replaced with a more diplomatically sensitive set depicting the achievements of Napoleon, to appease our French allies. Similarly, a series of Musical Celebrities had the German subjects withdrawn and substituted by lesser-known individuals from other nationalities.

Following the cessation of hostilities, the cigarette card phenomenon became enormous in the 1920s and ’30s. Some issues ran into hundreds of millions and bespoke albums were issued, with many cards being issued with adhesive backs ready to be stuck into the albums. These are known as ‘sticky-backs’ and today’s collector needs to ensure they are stored in a dry place to avoid condensation ruining the cards. Albums were usually sold by a tobacconist at 1d. each. In order that the text of the card was not lost when affixing it into the album, a full copy was pre-printed beneath the card.

Also after the war there was a decline in the issuing of military interest sets, as people had grown weary of warfare, and in the 1920s and ’30s they welcomed some escapism to turn their minds away from the economic and social problems of the time. Therefore, sets of entertainment stars and sporting heroes began to come to the fore once more. Companies began to develop certain niches, with Mitchell of Glasgow issuing many sets with Scottish themes, Lambert and Butler specialising in Motoring, and Ogden issuing sets dedicated to horse racing. Churchman went for a more unusual mix, including Interesting Door Knockers and Pipes of the World. The two most prolific issuers were Player and Wills. By the early 1930s cigarette card collecting had become so popular that the leading companies were printing as many as 40 million copies of each card, making an astonishing 2,000,000,000 cards per set of 50. This used up more than 300 tons of paper. During the interwar era, card issuers continued to be beset by the vagaries of contemporary events. Wills had prepared a set to mark the coronation of King Edward VIII, planned for 1937. However, his abdication in December 1936 saw the set discontinued, although a handful of sets were issued to the senior managers of the firm.

To reflect the growing demand from collectors to complete their collections, the London Cigarette Card Company (LCCC) was established in 1927 by Colonel Charles Bagnall. The company was soon issuing an annual catalogue, initially consisting of a four-page leaflet, which eventually grew into a four-volume publication which sought to list all trade cards ever issued. It was Colonel Bagnall who coined the term Cartophily to describe the hobby. The company set up premises in Cambridge House, West London, where collectors could come to browse the cards. The LCCC also began to produce Cigarette Card News in 1933. The standards of the publication were ‘accuracy, readability, informativeness’ and it sought to coordinate and explain developments in the hobby to a wider audience. The issuing of a regular newsletter and a catalogue meant that for the first time some realistic idea of card values was established.

Another development was the establishment of clubs for card collectors. In 1935 the Cameric Cigarette Card Club was formed by two young men, one of whom, Arthur Eric Cherry, was to die of cholera eight years later while working on the notorious Burma-Siam Railway while a prisoner of war of the Japanese. Cherry and an old school friend, Derek Campbell Burnett, named the club after themselves, a conglomeration of CAMpbell and ERIC. In 1938 the Cartophilic Society was formed, with C. Glidden Osborne OBE as its first president, and eventually in December 1964 the two organisations amalgamated to form the Cartophilic Society of Great Britain. Today the CSGB has around 1,000 members.

The popularity of the cigarette card was not confined to keen collectors. During 1939 advertisements appeared in the general press, giving a London West End address, offering two shillings per set for Player’s Modern Naval Craft, complete with the album. Many albums were sent, with each sender being paid with money drawn from a German bank. Colonel Bagnall, the founder of the LCCC, was suspicious because he knew that dealers were selling this album for 3d, rather than the 2s being offered. He reported this to Scotland Yard. The advertiser gave a plausible explanation to detectives, stating that the cards were intended for export trade with natives abroad in place of the usual beads and other small trinkets, so the police enquiry was dropped. However, in 1941 British intelligence discovered that every German U-boat had been issued with the albums, as a means of identifying British warships.

Ironically, the huge popularity of the cigarette card in the UK also proved its downfall. In 1939, as war broke out, Britain experienced significant paper and card shortages. It therefore became unsustainable to continue to issue cards in cigarette packets. Production of cigarette and trade cards ground to a halt as Britain fought grimly for its very existence.

After the Second World War, the major tobacco companies agreed not to resume the issuing of cards to any great extent. They did have provisional sets in stock on topics that were not time-limited, such as dogs and flowers, in case any of the other companies broke this gentleman’s agreement. Carreras issued a small number of sporting and entertainment sets under the Turf brand between 1948 and 1956, and Phillips also issued a few sporting collections. There were a couple of attempts to revive the cigarette card in the 1970s and 1980s, with Carreras again to the fore issuing cards with their Black Cat Cigarettes.

It was in the post-war environment that trade cards significantly increased in popularity, filling the gap left by the withdrawal of cigarette cards. From the 1950s onwards came a flood of cards issued with everyday grocery products such as tea, chocolate, biscuits, and cereals. The confectionary firm Barratt, who had already issued many football and cricket sets during the interwar years, established an annual series of football cards from 1947 onwards. Instead of being found in packets of tobacco-based cigarettes, these were to be found in ‘candy cigarettes’, later renamed ‘candy sticks’ to disassociate the product from the growing fears of cancer related to tobacco products. The company also produced sets of general interest, including History of the Air, Tom & Jerry, Birds, International Air Liners and Naval Battles. The albums in which these cards were to be kept became increasingly attractive, with brightly-coloured designs.

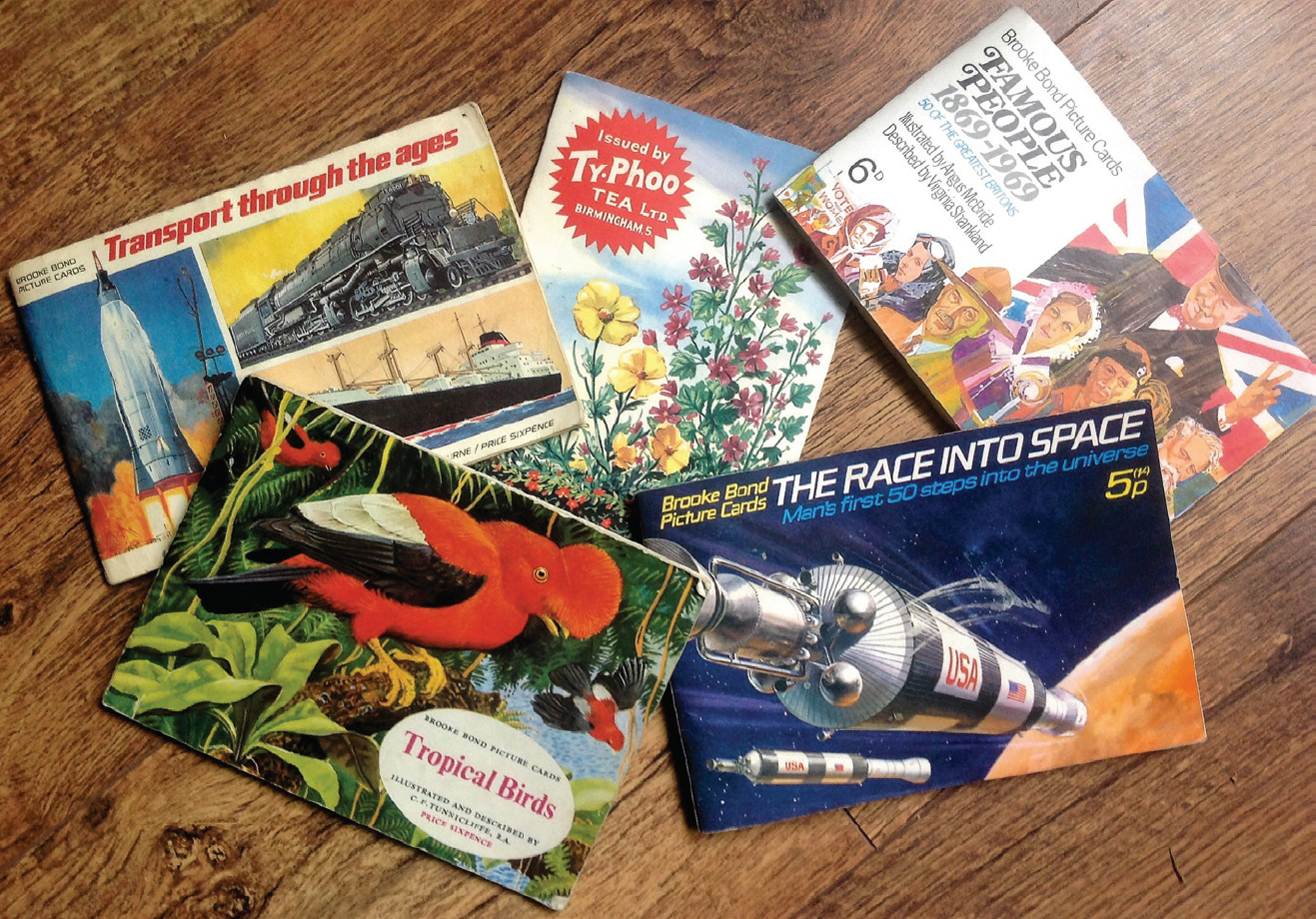

Many firms who manufactured tea also became prominent in the card collecting world, including Lyons and the Co-operative Wholesale Society. The most prolific issuer was Brooke Bond. Their first series in 1954 featured British Birds, followed by Wild Flowers and Out to Space. Like Wills and Player before them, Brooke Bond and the other tea companies brought out albums in which to store the cards. Such was the success of the whole venture that the company had to staff an entire department to service requests for odd cards, replacement albums and general queries. Their cards went through many reprints, sometimes with different coloured reverses, thus causing interest for future collectors who saw them as separate issues, even though containing the same information and picture.

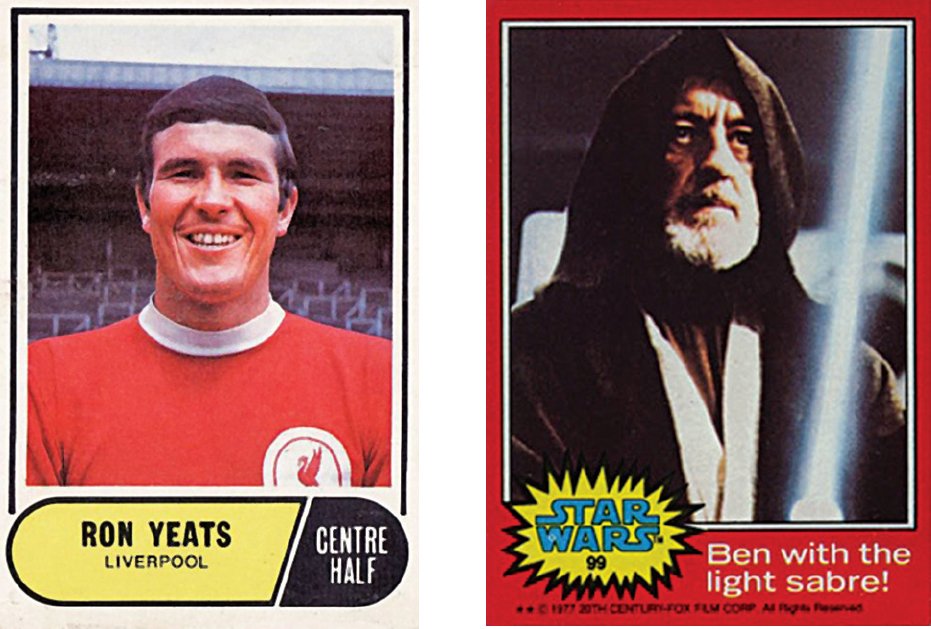

Some periodicals, such as those published by D.C. Thomson, continued their pre-war practice of issuing sets of footballers, cricketers and stars of stage and screen. The Sun newspaper ran a series of football cards through the late 1960s and ’70s. Their first set of football cards featured coloured drawings of twenty-two players given away with tokens from the paper. The 1970 World Cup gave the paper the opportunity to sell a souvenir wallchart for 1/-. There was space for 82 stickers which included current and past players, and flags of the competing nations. This was followed by a set of 134 Football Swap Cards and culminated in 1979 with a huge set of 1,000 Soccercards. In order to circumvent image rights issues, the cards were all artists’ drawings of the players.

Cards were also issued by cereal firms such as Kellogg, Nabisco, Quaker and Weetabix, Golden Wonder crisps and Penguin biscuits. Ice-cream firms such as Walls and Mister Softee produced sets, and Jacob’s biscuits celebrated the history of picture cards themselves in 1978 with 32 Famous Picture Cards from History, a selection of well-known examples with the text for the accompanying album written by the noted collector and card dealer Martin Murray. A mint set of these cards can be bought for a few pounds and can make an ideal introduction to the breadth and potential of cartophily.

Chewing and bubble gum firms found their products were in greater demand in post-war Britain following their promotion by the millions of GIs who had passed through the country en route to various theatres of war in the 1940s. Topps is the most renowned producer of gum cards. Early issues had an American bias, for example Civil War News, but later sets included All Sports and Winston Churchill.

A&BC Chewing Gum Ltd, formed in 1949 in Cricklewood, North London, was the foremost issuer of gum cards throughout its 25-year history. They are generally regarded as amongst the finest trade cards ever issued. Subjects of the cards varied from pop stars, TV series, film stars and football. During the 1950s, the company’s founders, remembering the popularity of cigarette and other trade cards before the war, thought that cards would be a good promotional tool for their gum. In 1959 they went into partnership with the American Topps Company and began to issue cards which had originally seen the light of day in America. Therefore their issues throughout the 1960s and up to 1975 were a blend of English and Scottish footballers, and entertainers who had succeeded in the American market.

The football sets often included extra giveaways such as paper pennants and small photographs. All the footballers featured on the card signed an individual contract with A&BC and were each paid £10 for the rights to use their image. This worked well until George Best’s agent asked for £1,000, which led to him not appearing in any sets after the 1968/9 season. Another player who queried the amount in relation to his status was Liverpool captain Tommy Smith. However, when it was explained to him that every player was paid £10, and that for many players who did not enjoy his prominence, this was a significant sum of money, Smith agreed to sign for that amount. In the mid-1970s Topps took over A&BC and continued to issue sets on sporting, entertainment and other themes in the UK. The author remembers buying large amounts of gum in order to accumulate the Star Wars card collection in 1977.

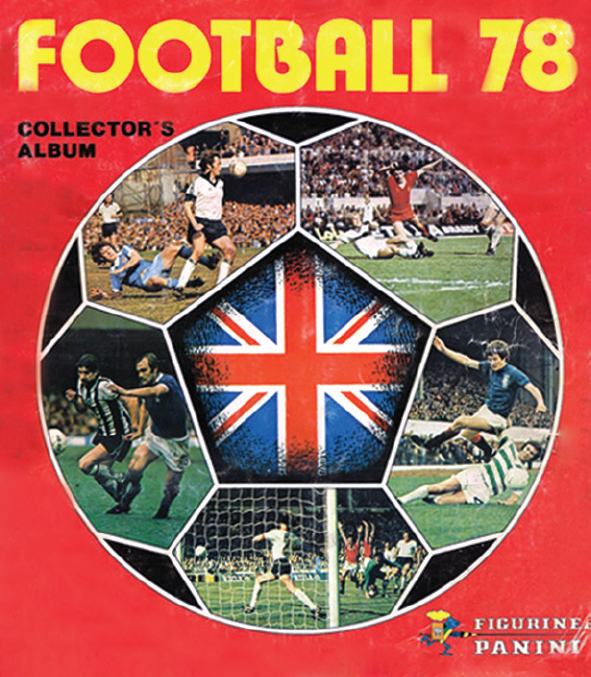

During the 1960s and ’70s, the emphasis in card issuing in the UK shifted from trade to trading cards, that is from cards issued to encourage consumers to buy a particular trade product, such as tea or confectionary, to card issues specifically for trading or swapping between collectors, often schoolchildren. From the 1970s onwards, one firm which has been a significant force in the UK collecting market is that of Panini. They operated a different model to the concept of receiving a card with each purchase of a certain product, usually giving away a sticker album and a small number of stickers with a newspaper or magazine, then selling the rest of the collection via newsagents in packets of 5 or 10. The idea was to encourage people to swap cards with their friends. Their first major foray into the British market was in 1978 with the Football 1978 collection. Its bright red cover contained a ball sectioned off into hexagonal patches, each containing and action photo. The set included the coveted ‘shinies’, the badges of the different clubs and the depictions of the cups and trophies they competed for. There was a wealth of statistical data for the young enthusiast to soak up. The collection also had room for the second division sides and the Scottish Premier League.

This author recalls this being the moment when the collecting bug hit, with him avidly buying the sticker packs with his pocket money and managing to complete the full set, although having to resort to the tried and trusted method of writing to the company for the three final stickers, which even to this day are remembered as Kenny Dalglish of Liverpool, Gordon Cowans of Aston Villa and the badge of the Scottish club Clydebank. Recently a full mint set of the first World Cup Panini collection, issued for the 1970 Mexico tournament, fetched over £4,000.

Very popular themes for today’s collectors include sets of 1960s and ’70s television series such as Thunderbirds, Star Trek, Dr Who, and films of that era such as Star Wars. More recent productions which have spawned collectable cards and stickers include the Harry Potter and Lord of the Rings series of films. Sporting collectables have never gone away either, with football and cricket cards remaining resiliently popular through companies such as Panini still issuing regular sticker sets of domestic and international players. More recent additions to the list of collectable sports include the American import of World Wrestling Federation fighters.

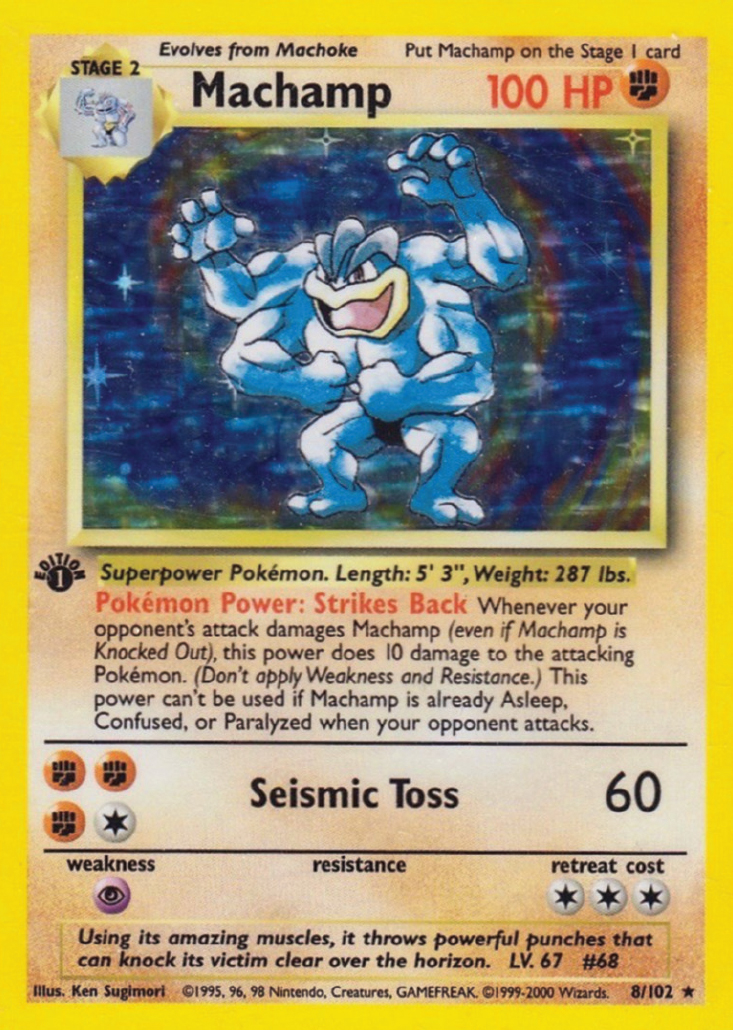

One huge phenomenon which thrust the card collecting scene back into the limelight for a while was the advent of Pokémon during the late 1990s. The collectable cards, which were used by the owners to play games against each other, continue to be a hit with many people. Recently an original US Pokémon base card set from 1999 sold for $106,000, despite it being less than two decades old.

Card collecting will continue as long as there are topics in which people can become absorbed, and companies willing to market cards which appeal to the collection instinct. Despite the digital age, the production of cards continues to expand and diversify. Whatever your interest, a card collection can provide a lifetime of interest and learning.

As cigarette cards were part of everyday life for millions of smokers and children for the first half of the twentieth century, it is not surprising to find that stories about cigarette cards often featured in the news. Even through the 1960s and into the twenty-first century, issues surrounding collectable cards still make the news headlines.

It was a fairly frequent occurrence for people in the street to be accosted by boys asking if they had a cigarette card to give away. This led to comment from a correspondent from the Birmingham Gazette of 10 January 1914, who criticised the way small boys would ask for cards: ‘Will yer give us yer cigarette card?’ The correspondent’s friend had been accosted by a boy the previous day who asked, ‘Excuse me sir, but will you please give me a cigarette card?’ He concluded, ‘Who could refuse a request translated into such polite and gentlemanly language?’

The Motherwell Times of 13 June 1930 reported that for a period the ‘cigarette card craze seemed to have died down’ but was now back. Interestingly, it was children of both sexes who were asking for ‘a cigarette card mister’, with tramway stops being the most likely places for this to occur. The paper was concerned with the danger of children being in the middle of busy streets.

As local newspapers tended to report cases of criminal activity heard in magistrates’ courts, these reports feature many instances of cards being linked to unlawful behaviour. For example, it was reported in the Aberdeen Press and Journal in 1923 that six boys aged between 10 and 14 had been charged at the Newcastle juvenile court with ‘extensive thefts of cigarettes and chocolates from local shops’. The boys’ defence was that ‘they said they had been anxious to get cigarette cards’. It was alleged that the boys entered shops through skylights, and in many cases merely opened the cigarette packets and took out the cards. The magistrate remarked that tobacco manufacturers should include cards in honesty in their products! The boys were remanded in custody.

Sometimes boys’ enthusiasm for asking for a cigarette card could lead to them being on the receiving end of retribution. The Sheffield Daily Telegraph of 3 October 1912 contained a report on the case of Edward Wheeler, a 43-year-old commercial traveller, who had been summoned to the police court to answer a charge of common assault against a 9-year-old boy. It was alleged that the boy saw Wheeler standing in a shop doorway and went to ask him for a cigarette card. Wheeler swore at the boy and poked his umbrella in his eye. The boy ran into his house shouting ‘oh mother; oh mother’. She had taken him to a hospital where his eye was operated on and he was discharged ten days later. Wheeler alleged in court that the lad had ‘tantalised’ him and pulled faces at him along with his friends. ‘In the excitement of the moment he raised his umbrella. The handle caught the knob of the door and became limp in his hand, the end catching the lad in the eye. It was a pure accident.’ Wheeler went on, ‘This cigarette card business is a great nuisance. They wait for you coming out of tobacco shops and they are a perfect nuisance.’ The magistrate evidently had some sympathy with Wheeler, who had his case dismissed, although he was ordered to pay £1 costs.

The Derbyshire Times and Chesterfield Herald of 24 July 1936 reported on cigarette cards being used for illegal gambling. At the Chesterfield Borough Police Court two men, Reuben Gascoyne, aged 23, and Walter Bedford, licensee of the Victoria on Shaw Street in Chesterfield, were accused of running a lottery. It was alleged that each customer entering the public house would be given a number. Gascoyne would then take a sum of money from customers who wanted to take part in a lottery. He would then buy a packet of cigarettes, and whichever number appeared on the card contained in the packet would take the winnings, minus Gascoyne’s commission. It was apparent that this practice had become widespread in the town, but was very difficult to detect as, as soon as a policeman entered the premises, the practice ceased.

A variation on this practice had been reported in the Lincolnshire Echo of 9 May 1934. Elijah Swift, licensee of the Plough Inn, Gainsborough, was fined £5 for allowing gambling over a cigarette card on his premises. One person would buy a packet of cigarettes and look at the card. Men would pay 3d to stand in a circle and count upwards in turn starting at 1, the winner of the jackpot being the one who called out the correct number on the card.

The cigarette card craze could also lead to tragedy. In October 1925 it was reported that a 9-year-old boy, Leslie Gardener of Kentish Town, was knocked down by a car while rushing into the road to pick up a card. The Lancashire Gazette of 27 April 1935 reported on the death of Horace Smith, aged 6, who was struck by a car while dashing across the road to ask a passer-by for cigarette cards. The Dundee Evening Telegraph of 12 October 1938 reported on Ronald Vigar, a 4-year-old boy who was tragically struck by a bus and killed while picking up a cigarette card from the road. The Northern Daily Mail of 24 April 1934 carried a short report on George Charles Lungley (8) of Northampton, who had asked a man for a cigarette card. Then, ‘Running back across the road he emerged from between two vehicles and ran into a car with fatal results.’

On a more positive note, there were celebratory stories concerning cigarette cards. The Bath Weekly Chronicle reported with pride in 1939 of the first man from the city to appear on a card. He was Captain G.J. Powell, a renowned pilot, who in August 1937 had taken the Imperial Airways flying boat across the Atlantic Ocean in the then record time of 14 hours and 24 minutes. Powell was the first British pilot to receive a master’s pilot license for both land and marine aircraft.

The Nottingham Journal of 7 August 1928 ran a story on Reginald Courtenay, a former Great Western Railway parcels office clerk at Slough Railway Station. Courtenay had given up his post to become an expert on heraldry and was engaged in painting small metal figures of ‘kings, queens, knights and ladies, all with exact heraldic detail’. He had begun his hobby due to a cigarette card. Courtenay told the press, ‘When I was at my work as a parcels porter, I was shown a cigarette card with a coat of arms, and when I remarked that it would be easy to paint it, the person who showed it to me was incredulous. I was once told that porters were not paid to think, but, just to show that some of them do think, I painted some coats of arms and exhibited them at the Paddington exhibition.’ His fame had grown and his figures had been ordered by Queen Mary and the Dean of Windsor.

In the same year, the value of the cigarette card was recognised in providing a general education beyond that to be found in schools. A Mr W. Hughes Jones, lecturing on the importance of children learning about architecture at the City of London Vacation Course on Education, stated that every boy and girl should be familiar with Greek temples, Roman arches and Gothic windows. ‘Boys should know the historical connections of a beautiful round arch of a railway bridge, to be found, for instance, on a cigarette picture card.’

The North Eastern Daily Gazette of 18 December 1914 reported on the intriguing story of one William James Valentine of Melton Mowbray, a civil engineer, who had made his will on the back of a larger cigarette card. The will was dated 26 April 1907. Unfortunately it was never recorded for posterity which card this was, or the contents of the will.

George Giddings, of Coldharbour Lane, London, gained fame through using cigarette cards to generate money for charity. It was reported in the Dundee Evening Telegraph of 12 November 1929 that Giddings was the ‘World’s Cigarette Card King’. For a number of years he had maintained a children’s cot at King’s College Hospital by dealing in cigarette cards. As the collecting craze ‘comes and goes in cycles’, Giddings’ business model was to collect individual cards and make them into sets to sell. In 1925 he had raised £41 and in 1928 £155. Giddings was assisted by his brother and both men were described as ‘cripples’ by the paper. They had sold sets as far afield as New Zealand, Madrid and Siam. Giddings commented, ‘It is remarkable the number of men and women who collect cigarette cards as a hobby.’ He had discovered that many of these collectors had incomplete sets and he set up a service whereby they could write to him in order to acquire the missing cards. After having had his appeal featured in the press some years previously, Giddings had been deluged not only by requests for cards, but with donations of parcels of cards too, including one from a Royal Marine with the curt note, ‘Damn Good Luck!’

Not all charitable enterprises were genuine. The Sevenoaks Chronicle of 10 October 1930 reported on a series of fake news items, including one that 250,000 cards would endow a crippled child with £2 a week for life. Another rumour circulating in Tunbridge Wells was that a firm of tobacconists would confer upon a blind person a pension of £1 per week if 1,000,000 of their cards were handed in. It was reported that a lady who had collected 10,000 cards had received a letter from the firm saying that the rumour was false.

One story which issued from the more reliable provenance of the British Red Cross Society via the Nantwich Guardian concerned a juvenile who had been knocked down by a car on the road outside King’s College Hospital, London, in 1915, and had to have his leg amputated. An unnamed cigarette manufacturer offered to give the child £1 per week for life if 10,000 of their cards were handed in. Many serving soldiers sent in their private collections to support the cause.

A cigarette card was used in the promotion of Marino cigarettes in Ireland. The Waterford Standard of 18 September 1937 ran a story about a card carrying the picture of the ‘mysterious Marino Man’. Those people who found his portrait in a packet of twenty would receive a half-share in a Hospitals Trust Sweep Ticket and an opportunity of winning £15,000.

In 1940, a Mr William Hagland was asked to stand as a surety in a trial at the London Police Court. He found he had left behind the means of proving his identity. Suddenly he remembered that he always carried with him a cigarette card from the Churchman’s In Town Tonight series, based on the BBC programme, in which he had appeared. When he produced it the magistrate accepted it as proof of his identity.

Hagland’s short biography on the reverse of the card is also worthy of note:

Engine driver for the L.N.E.R., Bill Hagland was with the Company for 52 years. He started life as a van boy, and became an engine cleaner in 1889, qualifying as an engine driver in 1906. The ambition of his life was realized when he was given charge of the ‘Aberdonian’ and other famous Scottish expresses. He has enjoyed a long married life and has had 23 children, 14 of whom are living, and 24 grandchildren. Besides appeared in ‘In Town Tonight,’ Bill Hagland has on two occasions appeared in the television programme in a B.B.C. talk.

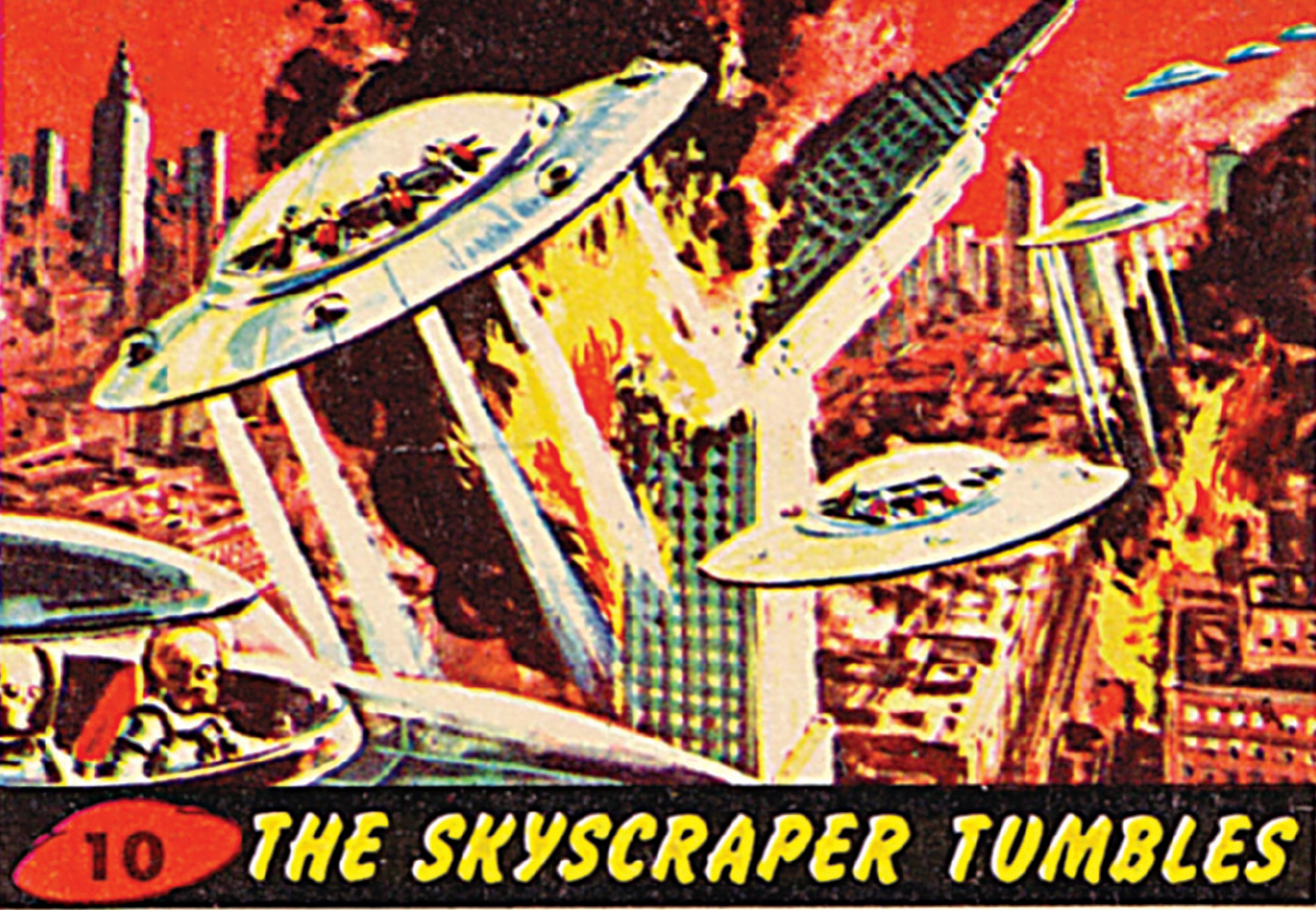

Card issues continued to make the news in the years following the Second World War. Topps caused controversy with their 55-card Mars Attack series, brought out in 1962, with very vivid artwork from Norman Saunders. Many parents considered there was too much graphic violence and implied sexuality in the cards. Despite Topps altering the content of 13 of the cards to reduce the gore and sexual content, public pressure caused the series to be withdrawn, not to return until two decades later (and then in an altered format). The brevity of their appearance makes them rare and collectable today.

A more recent collectable card series that has caused controversy was Pokémon. In 1999, Nintendo stopped manufacturing the Japanese version of the ‘Koga’s Ninja Trick’ trading card because it depicted a manji, a traditionally Buddhist symbol. The Jewish civil rights group, the Anti-Defamation League, complained because the symbol is the reverse of a swastika, which is considered offensive to Jewish people. On a similar note, in 2001, Saudi Arabia banned Pokémon games and cards, alleging that the franchise promoted Zionism by displaying the Star of David in the trading cards (a six-pointed star is featured in the card game) as well as other religious symbols such as crosses they associated with Christianity and triangles they associated with Freemasonry; the games also involved gambling, which is in violation of Muslim doctrine. The gambling aspect of the cards was again highlighted when, in 1999, two 9-year-old boys from New York sued Nintendo because they claimed the Pokémon trading card game had caused them to become problematic gamblers.

In 2012, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) publicly criticized the concept of Pokémon as supporting cruelty to animals. PETA compared the game’s concept of capturing animals and forcing them to fight to cockfights, dog fighting rings and circuses. PETA confirmed their objections in 2016 with the release of Pokémon Go, promoting the hashtag #GottaFreeThemAll.

There are three principal methods of printing used in trade cards. The first is Lithography, a word of Greek origin literally meaning ‘written in stone’. This is because this method of printing originally involved the drawing of the design onto a piece of smooth limestone. Paper would then be applied to the limestone and the drawing would appear in reverse. Therefore early artists had to draw their original design in reverse. In order to produce a multi-coloured picture, up to twelve stones would be needed, with the original design having to be copied onto each stone by a highly-skilled lithographer. As such, the process was extremely time-consuming.

The technique was perfected in Germany in the middle part of the nineteenth century, and many early British and American issue cards were produced in that country. Eventually, the limestone was replaced by a thin metal plate, and in 1908 the invention of the offset press meant that printing could be done much quicker, and the development of photo-lithography meant that designs could be transferred to the plate photographically.

Photogravure is another technique used to produce cards, turning photographs into a printed picture. However, the most widely used production technique was letterpress. In this process, firstly the design was photocopied, and then chemical processes were used to etch it on to a printing plate. The etching then stood in relief from the plate, and when ink was applied to this, it could be printed onto the card. Extra colours could then be added using additional plates to make the multi-coloured card.

A variation on this form of letterpress was the half-tone process. Here, a glass screen was placed between the camera and the design. The glass had a fine network of criss-cross lines, meaning that the photographic plate showed the design as a series of dots which became etched onto the printing plate, the number of dots per inch increasing the detail of the printing. The backs of cards were generally printed using letterpress using just one colour, and over time most cigarette cards were produced using the letterpress process.

Tobacco manufacturers often had their own printers dedicated to the manufacture of cards. For example W.D. & H.O. Wills of Bristol, part of the Imperial Tobacco Company, acquired the printing firm of Mardon, Son & Hall, which became responsible for card production. There was a team of about fifty designers, copywriters and artists employed for this purpose. One of the artists was Charles Sanderson, who began work at the company in 1931 after studying at the Exeter School of Art. He wished to become a commercial artist, specialising in still life. Sanderson’s particular passion was for nature, and he painted the pictures for the two Wild Flowers series He also painted the Racehorses and Jockeys series of 1938, finding it a challenge to get the correct shading of colours for the different horses.

For a series featuring portraits of monarchs of England, Sanderson had to travel to London to visit the National Portrait Gallery to ensure the colouring on the cards was correct. His diligence was rewarded when the set gained the approval of the Royal Family and Wills received a letter of official congratulations from the Lord Chamberlain. Sanderson recalled good working conditions, with plenty of light and a ‘friendly, paternal atmosphere’. However, he was never personally credited for his work, as artists were generally not allowed to sign the cards being only one part of the total creative process.

Another artist who worked for the company was Eric Craddy, who also painted the Story of Navigation series for Churchman. He was born in 1913 and won a choral scholarship to Bristol Cathedral School before moving to Bristol School of Arts. Apprenticed as a designer with Mardon, Son and Hall, he worked on original sketches of cigarette cards. On 9 November 1940 Craddy was commissioned as a second lieutenant into the Royal Army Service Corps before being transferred to the 2nd New Zealand Division. He was wounded and deafened by shell fire in the Western Desert and was later posted to Italy. After the war, he returned to Mardon’s Studio, retiring in 1973 having been senior sales representative for Wills, looking after their packaging requirements. His interest in the sea extended to being Commodore of the Bristol Corinthian Yacht Club.

The artistic value of the pictures on cigarette cards was recognised in an exhibition held at Messers Jones’s Stores in Wine Street, Bristol, in 1936. Original paintings which were used in the production of cigarette cards were to be on show, and, ‘it is bound to be of considerable interest to all those who enjoy the collection of cigarette cards.’ The Western Daily Press, which carried a report on the exhibition, went on, ‘The production of these has become a specialised business, and the printing branch of the Imperial Tobacco Company, Messers Mardon Son and Hall, have developed an extensive reference library and staff, on both the artistic and editorial side, for the production of this work.’

The collection of cards, which has been a feature of life for well over 100 years, is one that reveals fascinating lights onto the past and, as we live in an age increasingly dominated by digital media, one which reminds us of the pleasure of holding an artefact in one’s hand. It is also a hobby that remains resilient, albeit having undergone significant changes over the years. The next chapter will examine how to get started with the hobby of card collecting, and offer some advice on the potentials and pitfalls of cartophily.