CHAPTER 6

The locker room was crowded. The place was heavy with cigarette and cigar smoke, but it was bright and antiseptic under fluorescent lights. Down at the end of the room I could see a rubbing table, covered at that time with camera equipment, and beyond it two large coolers for soft drinks and beer. The color of the room was a sharp green, everything that color, except for the flesh tones of a “Miss September” taped to one of the big pillars. At the foot of each pillar were low rectangular boxes, about the dimensions of gardener’s frames, filled with sand from which a stumpy forest of cork tips protruded, some oozing smoke, and scattered among them were the chaw wrappers—“Day’s Work” or “Favorite” or the bright tinsel gum wrappers. Around the walls of the locker room were the open dressing cubicles—their wooden partitions topped with wire mesh, both wood and wire painted that ubiquitous municipal green. In each cubicle was a wooden shelf, hooks with coat hangers suspended, a seat with a footlocker under it, and then out in front a four-legged stool set on a little rubber mat. Sitting on one of these stools was the first ballplayer I recognized: Richie Ashburn, then playing for the Phillies, already dressed for the game in that club’s candy cane uniform except for his spiked shoes, neatly placed by the stool, and he was calmly sitting there turning the pages of This Week. Most of the other cubicles were occupied by players in various stages of undress. No one looked at me as I stood there, and finally I sidled over to an empty cubicle and put my bag down on the seat.

I stayed in there briefly, looking out. Most of the players were moving around actively—talking and joking. At the mouth of their cubicles others were sitting motionless on their stools, staring down at their stocking feet or out into the locker room with eyes that seemed glazed. I’d seen that look before, remembering it from years ago when as kids we went with our autograph books and the bubble-gum cards to the midtown hotels where the ball teams stayed. I have a difficult time memorizing faces but the ballplayers who were lobby sitters were easy to spot: large men with these vacant expressions, as I remember them, sitting in armchairs so low that they stared out between their knees at the lobby. Their jaws worked slowly on gum. You never saw them reading, and I used to think that, like Rogers Hornsby, they were so dedicated to the game that they didn’t read for fear of straining their eyes unnecessarily. Hornsby, after all, to keep his eyes rested, never went to a film in the twenty years of his major league career. Their faces were devoid of expression, as blank as eggshells, yet peaceful as if a mortician had touched them up. They sat for hours, quietly waiting until the time came for them to leave for the park and the rigors of their profession. Only their jaw muscles worked slightly on the gum like a pulse throb as they stared calmly out at the people moving in the lobby among the potted palms. They never looked up when they signed the autographs. They took the proffered book and the pencil, worked the big writing hand briefly across the page, and you took the book off to a corner of the lobby to gloat over the signature—that tangible evidence that you’d been in the presence of a major league star. The first ballplayer who ever spoke directly to me was John Mize, then the big Cardinal first baseman, later a Giant star who hit 51 home runs in the 1947 season.

He said: “You a ballplayer, son?”

“Yes, sir,” I said eagerly. “I play on the St. Bernard’s Giants!”

He looked up from his armchair. “What’s that? That a new triple-A club?’

“No, sir,” I said uncomfortably. “That’s my school.”

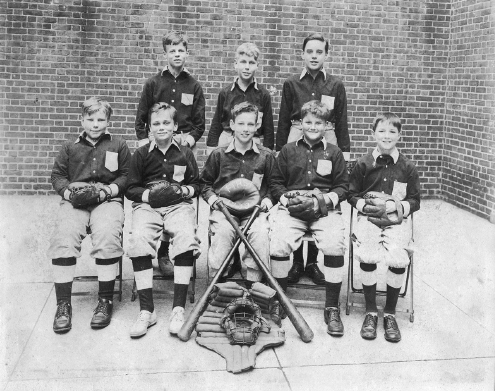

St. Bernard’s School baseball team. The author is top left. (Plimpton Estate)

He could sense I was embarrassed. “What’s your name?” he asked.

“George,” I told him.

He put “Good luck to George and the Giants” in the autograph book, and he asked the others with me for their first names to put in their books. When he left the lobby we followed him down the street, at a respectful distance, and when he turned in to a Nedick’s hot-dog stand, we stood and peered through the plate-glass window. We watched him drink an orange juice. Then he came out and got in a taxi. We talked about him for days and I almost became a first baseman. His was the prize autograph in the book. He dotted the i of Mize with a little circle. I’d never seen an i dotted that way and I did it myself for a while until the teachers at St. Bernard’s stopped it.…

Autographing took up a big portion of a ballplayer’s day. To my surprise, even in the locker rooms they were kept at it. Opposite my cubicle was a long table at which sat a group of players writing their names on baseballs in earnest absorption. I went over finally and asked if they could point out Frank Scott. One of them looked up and nodded at a small man at the far end of the room carrying a large manila envelope which he waved heatedly as he talked. “That’s Frank over there,” the ballplayer said, his pen poised, and then he bent back to his labors. They used ballpoint pens, turning the baseballs skillfully as they wrote, and when they were done they put the baseballs in the big red Spalding boxes.

When I went over and introduced myself, Frank Scott looked at me doubtfully. But if our arrangements had skipped his mind, he remembered them when I mentioned the purse Sports Illustrated had offered; he shook his manila envelope vigorously and brightened up. “Yes, yes, yes,” he said.

“Is everything arranged?” I asked. “Am I going to pitch?”

“Tell you what,” he said. “You just wait around here someplace. When Willie Mays gets here—he’s a little late—we’ll talk to him. After, we’ll go on down and talk it over with Mickey Mantle. They’re the captains. They gotta give the final OK.”

As he talked, his eyes roved the room, and his sentences were thus delivered with little nods of greeting, small gestures of recognition as he’d glimpse someone he knew. Two men wearing long overcoats came up and gave him the big hello, and I started back to the cubicle. I thought about getting dressed in my baseball clothes, but when I opened the grip and saw the leather of the glove, I started looking around the locker room for the trainer.

It was at that moment that Willie Mays arrived—the great Giant center fielder, the player Leo Durocher once described in a paroxysm of admiration as “Joe Louis, Jascha Heifetz, Sammy Davis, and Nashua rolled into one.” He came into the locker room with a rush, shouting greetings in his high, rather squeaky voice, an arm upraised, waving—smaller, much smaller in stature than I’d imagined, and yet so ebullient the locker room came alive the moment the door swung shut behind him. Suddenly you had to raise your voice to be heard—the room crowded, everyone talking—and in the din it was easy to understand what has been said about Mays: that he would help a club just by riding on the bus with it. His natural enthusiasm was what was infectious—a characteristic one doesn’t often associate with the professional. Watching him, you could see that it was almost an unspeakable pleasure for Mays to be where he was: there in the locker room in the blue-green depths of Yankee Stadium, joking with the players, every phrase punctuated with cusswords used not in ill humor but in warmth, in delight, everybody grinning at him as he moved slowly toward his cubicle in the familiar setting of that locker room—the spitboxes, the red Spalding cartons, the uniform waiting on its hook, an afternoon of baseball ahead.…

I waited until Mays had completed his tour and then Frank Scott took me over for introductions and to tell him what I wanted to do. Mays listened with his head cocked to one side; when Scott had finished he rolled his tongue in his mouth, considering the matter, and then he looked at me and grinned. “You, man, you,” he said, “you gonna pitch?” and up came a finger, pointing, and then he whistled—one high piercing note—following that with a soft sibilant cussword, drawing it out as an expression of reflection, and then he began to laugh—gusts of laughter so infectious that the knot of people around him began bawling with laughter. It was his way of saying that as far as he was concerned everything was OK because Scott touched me on the sleeve and we left for the Yankee locker room to see Mickey Mantle.

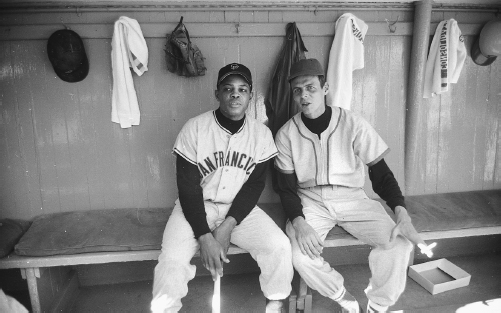

“Here is Willie Mays. I don’t remember what we talked about.” (Garry Winogrand)

“I mean what did he say?” I asked. “What was all that about? Is it OK?”

“Sure,” said Scott as we hurried down the corridors. “Sure.”

Compared to Mays, Mantle seemed stolid, almost indifferent as Scott talked to him. During his early years as a Yankee he kept a cap pistol in his locker, and for a couple of seasons around the major league circuit he and Billy Martin used to bang away at each other while Yogi Berra and some of the others would join in with water pistols. But the Mantle I was introduced to by Frank Scott seemed long past the cap-pistol stage. His jaw moved slowly and barely perceptibly on gum. When Scott had finished he gave me one brief flick of his eyes, and he said, “Yeh, yeh.” He wanted to know about money, it was apparent, and Scott talked to him earnestly—and very softly as if he were giving him counsel, a hand on his shoulder. I couldn’t hear what they were saying finally, so I looked around the clubhouse. It was more spacious than the visiting team’s quarters. Even the sandboxes were larger. Being the home club’s quarters there was less of the transient and bare atmosphere of the other. Through the door of the manager’s office I could glimpse framed caricatures and photographs of Casey Stengel—Stengel, who had said of Mantle in his rookie year, “Well, I tell you this—I got sense enough to play him.…”

I looked back at Mantle. He was still listening to Scott, nodding his head now, affirmatively it seemed—so it looked as though I was really going to get the chance to pitch. While Mantle and Scott continued to whisper I thought perhaps I should find Elston Howard and talk to him. He was scheduled to catch for the American League and thus—though he didn’t know it at the time—would be handling my pitches. I’d hoped to see him (and also Stan Lopata, the National League catcher) to discuss signals and try to make up what pitchers call “the book”—that is to say, a reference list of the strengths and weaknesses of the opposing batters. Actually, what distinguishes major league players is that they have no pronounced batting weaknesses. A player wouldn’t last who had serious difficulty with a specific pitch. But there are types of pitches a batter prefers, and areas in his strike zone where he’d rather find a pitch. The intention should be, then, to avoid the batter’s power, not to think about his weakness but pitch away from his strength. My ability to take advantage of any such knowledge was naturally questionable; but if I was to emulate big-league pitching I felt I should go to the mound with a few tips of this sort. Years back, Crazy Schmidt of the Cincinnati Reds was troubled by a sievelike memory and actually kept his book on his person—in a loose-leaf notebook which he tugged from his hip pocket for reference as each batter approached the plate. “Base on balls” he is supposed to have written opposite the name of Honus Wagner, the great Pittsburgh slugger who won eight National League batting titles.

But I couldn’t find Howard, or even recognize him. There were nameplates above cubicles, but they read Rote, Gifford, Conerly, etc.—players on the New York football Giants. Their season was just under way; on a blackboard set against a far wall were the chalked circles and arrows of a football diagram. The only evidence that baseball players were on hand was an inscription someone had written in chalk on a second blackboard. “Mickey Mantle,” it read, “and his bloodshot eye nine.”

Frank Scott plucked at my sleeve. Mantle had gone back to his stall. “Well, it’s all set,” he said. “Listen. You’re on at one thirty, a half hour before the game’s scheduled to start. Both leagues’ll send up eight men against you. No need to send up the pitchers. The team that gets the most bases’ll divvy up the thousand dollars. They get one point for the single, two for the double, on up to four points for the homers. Right?”

“Sure,” I said.

Scott produced a small, chipper smile. “You better get dressed,” he said, and he told me he’d see me on the field.