CHAPTER 18

I didn’t see anyone in the locker room. I took off the baseball outfit slowly and sat for a long time in the cubicle looking down at my bare toes, working them up and down, and thinking of nothing, trying to keep the mind blank because when you thought back to what had been going on just minutes before, the excitement began to jitter through you again. Finally I hopped up and went into the shower and stood under a nozzle that malfunctioned and worked in spiteful gusts. The soap in the metal dishes was an astonishing pink color. The dirt I’d scooped up in front of Don Newcombe ran from my hair for the drains in rivulets of red mud. The water was cool. The trainer told me later he hadn’t expected anyone to be in the showers so early; after all, he wanted to know, how many pitchers were driven to the showers before the game had even started. But the cool water was pleasant. Under it, luxuriating, I remembered Bruce Pearson, the barely articulate catcher from Mark Harris’s great baseball novel Bang the Drum Slowly—which our generation thought good enough to make Ring Lardner and the epistolary device of his You Know Me, Al cork up and take a backseat when it came to baseball fiction—and I thought of Pearson speculating idly with his teammates about the best moments of baseball… how even hitting a foul ball was part of it, to look up and see how high you drove it, and how the best part of all perhaps was coming in stinking from the sun and ripping off the suit and getting under the shower and thinking about eating. I thought about it because for the first time that day I was suddenly hungry. Roy Campanella once said that you had to have an awful lot of little boy in you to play baseball for a living. So it was, when you recalled it, that the simple, basic sensations came to mind—like being hungry when it was all over, and the sluice of shower water on your arms, and before that, on the field, the warmth of the sun, and the smell of leather, the three-in-one oil sweating out of the glove’s pocket in the heat, and the cool of the grass and the dirt when the shade fell across it late in the afternoon, and the sharp cork sounds of the bats against each other, and the rich smell of grass torn by spikes—all these condiments to the purpose, to be sure, which was the game itself, and winning… but still such a part of baseball with the other sounds, and what else you saw, and felt, that finally the actual event itself was eclipsed: the game and its feats and the score became the dry statistics, and what you remembered were the same pressures that once kept you and the others out in the long summer evenings until the fireflies were out and the streetlights shining dimly through the pale-silver underside of leaves, and you groped at the edge of the honeysuckle and threw up that last one high fly for someone to catch and hoped they would see it against that deep sky—and the fact that your team in the brighter hours of the afternoon had lost twenty-four to six and your sister had made eight errors in right field wasn’t important. The disasters didn’t amount to much. Standing under the shower I found myself thinking not of the trembling misery of the last minutes on the mound, but of Ed Bailey and how he had reared up out of his crouch and given recognition to that roundhouse curve of mine. I thought of those two high flies that Ashburn and Mays hit, how they worked up into that clear sky, and how you knew they were harmless and would be caught. You could be a bona fide pitcher like Hal Kelleher of the Phillies and suffer the indignity of allowing twelve runs in one inning—which he did back in 1938—and in desolation punt your glove around the clubhouse while the trainer stood in a corner pretending to fold towels… and yet that startling statistic was not what Kelleher would remember about baseball. What he would remember made you envy him, and all the others that came before and after who were good at it, and you wondered how they could accept quitting when their legs went. Of course, there were a few who didn’t feel so strongly. In 1918 a rookie named Harry Heitman walked in for his major league debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers, gave up in succession a single, a triple, and a single… was taken out, went to the clubhouse, showered, left the ballpark for a recruiting station, and enlisted in the United States Navy. To hell with it, he said.

But when I dressed in my street clothes it was with regret that I stuffed the baseball outfit back into the carryall. I found myself looking around the locker room carefully so that I could remember it, not to write about it as much as to convince myself that I had been there. I noticed the red boxes still on the table, filled with baseballs the players had been autographing earlier, and I went over and looked down at them. I had an irresistible urge to sign one of them—perhaps just a scribbled initial. I started looking for a pen. I felt the whole afternoon was slipping away and had to be commemorated, even if by this sad sort of graffiti—scratching a name so that there would be evidence, no matter how insignificant, to prove that day. It seemed very important. But the door of the locker room swung open. Some players came in, and I never got the thing done.

When I emerged from the clubhouse into those crowds above, I could feel it slipping away fast. The baseball diamond and the activity of the players, now engaged in their regular game, seemed unfamiliar and removed. Someone smacked a ball which was caught after a long run but the steel pillars cut my view and I couldn’t distinguish either of the participants in the play. No one recognized me as the Sports Illustrated pitcher as I went down the aisles looking for an empty seat. The lower stands were crowded and I turned and headed up the ramps and finally found a seat at the top of the stadium in the upper deck. I flagged down a hot-dog vendor, and behind him the beer vendor, and far below on the field Willie Mays stole a base as the crowd roared. Over the rumpus of noise I heard the prying voice of an usher. He was leaning in from the aisle, demanding: “Hey, chief—gotcha ticket sub?”

I had just paid for two hot dogs and was at that moment handing the beer vendor his money, the focal point of a congestion that then included the two vendors, the usher who wanted to see my ticket, and behind him, carrying a red thermos jug, a worried-looking man in whose seat I was obviously sitting.

“You mean my ticket?” I said, stalling for time, wondering how I could announce with any authority to that group that I’d legally entered the stadium by the players’ gate.

“What’s this—the upper deck?” I said, looking around. “I must be up here too high. I think I belong lower down—in the mezzanine,” and I peered around aggrieved, as if some other agency than my own legs had deposited me there.

I went back down the ramps with my hot dogs and the beer looking for another seat—in a limbo state of being neither ballplayer nor spectator—as nomadic as the youngsters who scuttle in without paying and are flushed like shorebirds and flutter down two or three sections to settle again until the ushers come down the aisles with their big dusting mittens.

I went down to the lower grandstand to the field box where Toots Shor was sitting with his family. There weren’t any extra seats so I crouched briefly in the aisle. Shor looked around. “You’re outa condition,” he said. “Whassamatter? At your age I could’ve pitched to ten dozen of those crumbums.” He leaned out and pushed a jab into my rib cage. “But what the hell,” he said. He turned back to the playing field. Billy Martin was in the on-deck circle and Toots shouted at him: “Hey, Billy!” Martin was dusting the bat handle with the rosin bag. Toots shouted again: “Hey, Billy!” over the hum of the crowd, turning heads by the score in our vicinity, and Martin looked around. “Smack it, kid!” Toots shouted. Martin indicated with a shrug he couldn’t hear over the crowd noise. Toots lifted himself out of this seat. “I said smack it!” he bellowed. He made a ferocious gesture with his arm to illustrate what he meant, and Martin nodded and went back to dusting his bat with the rosin bag.

I remembered it afterward, very clearly—crouched before Shor, working on the second hot dog, and watching his neck bulge with that effort of communication: I thought what a long way it was out there over those box railings—not only a distance to shout across, but so remote and exclusive that it seemed absurd and improbable that I had been out there. It all seemed not to have happened, and later, tired of my wanderings, when I tried to explain to a sympathetic-looking usher who finally gave me a seat why I didn’t have a ticket, I couldn’t seem to do it with much conviction. I kept my voice low talking to him to keep anyone else from overhearing.

But I had the reality for a while. Even late that afternoon, when the game was over, I had yet to sink into the true anonymity of the spectator. At the last out I watched the kids leap over the box railings and run for the pitcher’s mound. Baseball finished for the season, the stadium guards didn’t bother to throw their protective cordon around the infield. The youngsters’ high cries drifted back into the stands: Hey, lookit, lookit me, I’m Whitey Fawd—and they jostled each other for the chance to toe the rubber and fling imaginary fireballs to imaginary catchers. The gates were opened and the spectators began to file onto the field, headed for the exits in deep center field. Many of them stopped and stood on the top steps of the dugout, and stared at the empty wooden benches. But I didn’t go down on the field—not that day, at least. I knew I’d been out there. So I left the stadium by the ramps behind the stands.

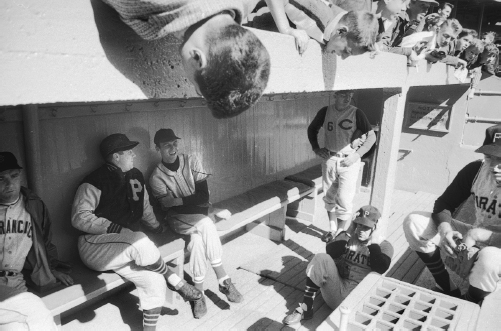

Curious youngsters peer into the dugout for a glimpse of their heroes. (Garry Winogrand)