Conclusion: After Social Media Mania

No one wants to face the reality that this [alphabet/google] is an advertising company with a bunch of hobbies.

An ex-Google executive, quoted by Max Chafkin and Mark Bergen, in BloombergBusinessWeek1

On February 2, 2017, Snapchat filed form S-1: the drive for the IPO was beginning. The opening image of the document was a bright yellow page declaring that “Snap Inc. is a camera company.”2 The promise of the company is “reinventing the camera” which changes how people “express themselves, live in the moment, learn about the world, and have fun together.”3 At this point Snapchat lays claim to the core affordances of every major social network: the personal expression and community of Facebook, the temporality of Twitter, the locative awareness of Foursquare, and the creative inflection of Pinterest. This should be the new homepage of the phone. Following this statement of purpose is a history, tracing the evolution of their product punctuated with the release of major features including the capacity to “barf rainbows” and virtual goods sales. Snapchat does not own a physical infrastructure relying on Google Cloud to deliver performance for users with advertising almost exclusively as a revenue driver. Daily active user growth is failing, Facebook’s Instagram is successfully flanking their key advertising concept—placement in the story.4 For all the claims to Snapchat providing a “new” model of social network organization, readers of this book would recognize this as a platform for producing a supply of possible social impression sites for sale, arbitrage; dressed as the magical reinvention of the camera, alchemy.

Snap’s IPO was read as a social sign of the market and the users. Kevin Maney, writing for Newsweek, proposed that the app is a user vote for privacy and the looming prospect of state surveillance by the Trump administration.5 Therese Poletti framed the Snap IPO as a competition between two rival camps: those who believe that Snapchat is an advertising company with “staggering overhead” and a stock to be purchased and amassed like a fine wine.6 Changes in potential user behavior provide leverage for alchemy, reduction to a sales platform for virtual goods (filters) and advertising not as much. Disrupting the camera itself could be profitable. The major points of risk, aside from cooption by competitors: litigation and political change. This is not to say that Snapchat does not afford users an enjoyable experience, but that at the end of the day, it is a stickers app for an ephemeral messenger, likely just a feature, not a network in itself.

This book was organized around key terms used to sell social media to publics, markets, and governments. The theory developed through the chapters details the ways that these companies explain social phenomena and is explained by the cultures they express. Rather than offering a summary of the contents of this book, this conclusion remains true to the spirit of business though by answering two of the most frequently asked, practical questions about the future of the social media industries: is this a bubble and is what is the next Facebook? Brief answers to each question: yes and no.

Is social media a bubble?

Many social media companies exist in what we should understand to be a bubble. Bubbles are interesting topic as they are qualitatively diagnosed. Bubbles tend to be negative. Economists take a number of different, but not incompatible, positions on bubbles. Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff provided a comprehensive history of bubbles and crises, treating the bubble as an aspect of a system that produces recurring crises more than as an anomaly.7 Without beta or volatility, returns can be difficult to come by. George Akerlof and Robert Shiller elected not to define bubbles, but their account of shifting psychological positions is straightforward in suggesting that bubbles are a feedback loop.8 Again, this would challenge the idea of an efficient market by embracing the idea of an emotive, rather than rational, base for economic practices. It is not unreasonable to argue, as Peter Garber has, that the historical episodes known as bubbles are not in fact defects of mass psychology, but rational choices made based on the fundamentals at the time.9 The fundamentals as we know them rarely escape the narrative of the market that produces them. Hyman Minsky’s “Financial Instability Hypothesis” supposed that capitalist economies tend to drift during good times toward increased speculation; bubbles are a feature of forgotten pain.10 Firms begin in conventional stable configurations, take on increased hedging activity, and eventually become unsustainable schemes. Minsky expanded the sorts of relationships that would be considered in the production of bubbles beyond capital and labor to include financial relations—this would get at the complex webs of relationships and feedbacks that drive an economy. Communication research would take this further to include the discourses of those financial relations. These common uses of bubble by prominent economists get at the reasons why bubbles are so troubling: they are destructive and yet attractive.11

The definition of a bubble that could be derived from the communication studies literature, and the one that will be taken here, is that a financial bubble is a positive affective cascade. In this cascade, the preferred values and aesthetics of the culture making transactions are attuned to the dynamics of the subject industry. G. Thomas Goodnight and Sandy Green’s theory of bubbles would suggest that the basis of the bubble is a spiral of attention, a cascade of energy into the image of what the economy should be.12 Affective investment in the bubble can drive the creation of discourses that make that bubble appear to be sensible. Evidence of this can be found in the highest formulations of disruption discourse where basic economic theories might operate backward. The hopes, dreams, fears, and fantasies that sell the bubble become working theories of the economy. Bubbles play with the space between the diachronic and the synchronic; the broad stretch of the time and the present moment shift into each other. Bubbles incorporate fundamental economic facts into a logic of feeling.

What does it mean for there to be a social media bubble? First, the valuations of these companies vastly exceed what traditional models would suggest are stable. Chapter 2 argued that valuation is a political process with substantial artistic ambiguity. Analyses of what the market would bear are then paired with disruptive fantasies to justify current securities prices. Alchemic magic obscures the actual process of monetization as well as the role of business law in the life of any given company. Explanations of the system change to suit the bubble. The underlying fault of the bubble is explained in the epigraph of this chapter—these are advertising companies that have hobbies. If they are lucky, the hobbies become lucrative businesses. Although the greatest of these firms control their ecosystems significantly more than their predecessors, they are still advertising companies. Demand is ultimately inelastic, there is not an infinite supply of money to chase advertising opportunities on these networks, and there is not infinite attention to be paid across networks. Securitization and disruption have allowed these companies to work around these truths, to a point.

Strategies for deterring the formation of bubbles are important as no state actor would want to be responsible for popping bubbles—they are after all made good feelings. Feedback loops in economic phenomena would have amplified reactions to new information as the concepts that are disavowed or fetishized are often deeply interlinked.13 At first this bubble might appear to be in a single sector; thus a pop would not be terribly destructive. Given the degree to which many fates are tied to these particular stocks and stories, the pop of this bubble could be substantial.

The biggest threat to the social media bubble comes in the decline of social media itself. If the network isn’t fun, why use it? If the network stales or the attention lens is mismanaged, the story of the company would simply fall apart. As companies become increasingly desperate to provide some backing for their value proposition they will add features, clutter interfaces, and demodulate their own affective balance. At some point, the product managers at Facebook will decide that they might fare better if their now sedate, but enjoyable, network vibrated with the rage with Twitter. Social networks like Yik Yak struggled with the balance between secrecy and affinity; secretive locative networks are highly energetic and nasty; there is no stability as in an affinity network like Facebook. Television companies easily fell into the trap of reality programming. It was engaging and impossibly cheap. It was a short circuit in the industry that was too tempting not to connect. Fake news, as discussed in Chapter 3, connected much the same circuit for Google and Facebook. Maintaining the health of a social network over the long term will require careful affective modulation and attention to changing cultural norms. Epidemiological modeling of the collapse of Myspace, and the experience of other collapsed networks, suggests that network abandonment could come as a swift contagion.14

The underlying cultural moment of rapid social network growth is passing. This is no longer the relatively benign problem of the filter bubble, but the much more vexing problem of decreased sharing. The perception of state power and surveillance is pronounced and rise of nationalism has transformed the position of the state in the lives of many. The affective world that saw Facebook burgeon is gone. Boundary rules and choices made in that moment will not be made again. It would not be surprising to see these firms increasingly act like media companies, curating streams of content and stabilizing their products to avoid future losses. Snapchat has become the newest darling for this exact reason. Discover, Snapchat’s broadcasting feature, has been strictly controlled. Instead of the social media of the past which depended on the wisdom of crowds, Snapchat depends on the wisdom of editors and contracts. On the flip side, networks like Twitter and Reddit struggle to deal with their own users who express values and act in ways that will destroy their networks. The everyday life of the average user is a powerful response to utopian fiction.

The threat to monetization itself is somewhat muted. Strong platforms are deploying improved metrics and increasing transparency to accommodate market demands. Bubble bursting on the advertising demand side would not be a result of a sudden increase in payments, but the revelation of inelastic demand. Better auditing tools would allow advertisers and the market as a whole to see the maximum possible value of online advertising. Seeing the summit of the mountain could be quite disheartening.

The final burst scenario comes in the form of increased state power, especially the resurgence of aggressive state control of the communication network to counter another state. Politicians have already postured to this effect.15 The germ of this idea already appears in the critique of fake news. More advanced efforts might use the combination of weak social norms, media literacy, and the porous control of social networks to manipulate populations. Contrary to Zuckerberg’s utopian image, Facebook is not well positioned to make governments more democratic or the world more open. Compulsory participation in a bland social network would be a staple of this other world. By the time we reach this conclusion, social networks will have shifted to have a pseudo-government mandate and surely the bubble will have burst, that is unless the bubble is in what would be a state-sanctioned social network monopoly.

The next Facebook?

What is the next Facebook? A persistent question for social media researchers. The answer is simple: there is no “next Facebook.” Affectively, the ascent of social networking is much like the boom of the 1990s is not a repeatable formula; it was an event.16 Facebook grew because of a combination of factors related to the prior work of other social networks, the perception of Facebook as an alternative to Myspace, the increased availability of high-speed internet connections, the converged smartphone, the high level of investment capital, and the discovery of enjoyment in computer-facilitated ambient awareness. Combine those with a stock market desperate for a big hit in the post–financial crisis slump, and a legend is born. Causation in complex systems is fractional and difficult to establish. Success would be explained as anything except a confluence of factors beyond the control of a single individual. Instead, Facebook is described as the creation of a business genius, be that Zuckerberg, Sandberg, or the venture capitalists that backed the firm in the early days. First, the conditions are not ripe for a new network to emerge. Second, there are structural factors that would see Facebook maintain an advantage in the market.

Facebook is and thus has an advantage. Network effects are powerful; the future for Facebook (and most disruptive firms) is to transform into companies that interface with elements of the market that are traditionally understood to be more lucrative, such as transaction processing. Chapter 3 describes this situation at some length; the promise of access to new sectors drives the value of a social network. Facebook is the largest and strongest social network; the underlying wealth of data and physical capacity provide Facebook with a profound edge over potential competitors. This tends to protect Facebook from challengers as their products lack the network development to be affectively engaging. Building a social network is an engineering challenge. A new social network would need both a strategy for being interesting and engaging and the infrastructure to function in the first place. This is especially true as Facebook controls the market space of the affinity network; it would be far more likely that a locative, temporal, or creative network could be supplanted. In any case, a network evolving as a restaurant recommendation engine will not take on a social role similar to a family member.

Users are increasingly less likely to share information publicly: Facebook is working to understand the declining click count.17 The affective conditions that incited users to share large volumes of personal information with little active censorship have passed. Once they have experienced the perception of presentational rules’ violation there is no reason why they should trust those networks again. Returning to the story of the failure of Google+ from the introduction of this book, the conclusion of that story is not that privacy did not matter or that users did not care, but that they did care, and that changing their use of social media (by sharing less) was more convenient than using Google’s contrived interface.

This does not stop optimistic entrepreneurs from trying to make 2006 happen all over again. New networks come in waves. This does not mean that the feelings of users will not change over time, or that more specialized networks might not appear that map onto other relational functions. A single network that would take on all the relational roles of Facebook is not coming; Facebook may have a role as an ambient kin-keeper, an aspect of infrastructure. Pinterest, Yik Yak, Snapchat, Kik, WeChat, and many others will surely come, each with a different selection of affordances.

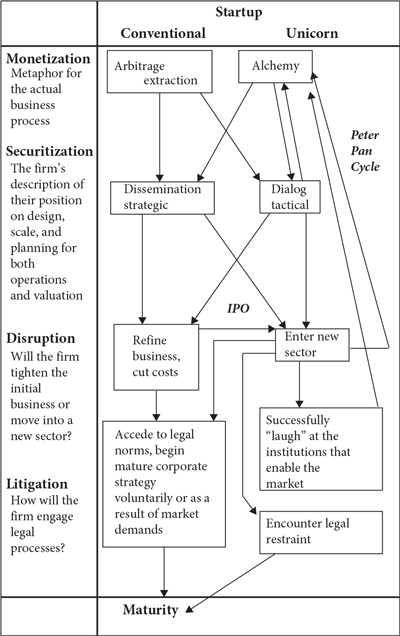

Figure C.1 Industry life cycle.

In order to remain in the bubble, firms must find ways to return to alchemy, or, as it is described here, the Peter Pan Cycle. As firms make choices that bring them down the conventional, rather than the unicorn, path, they will mature and be judged as companies, rather than magical apparitions.

Firms that have ascended the dream logic to become the unicorns, the rightful inheritors of the pure networks of the past likely, will rely increasingly on the discourse of disruption rather than pure monetization. Not surprisingly, these new services will use Facebook network integration to facilitate social tracking and authentication. These services may claim that they will be the replacement for Facebook—yet for all their possibility has little chance to be anything aside from niche businesses. The legal logic of the API and the patent thicket favor the incumbents. Business-to-business service is a very different industry than primary social network service. Managing a social network is difficult; providing the backbone that allows other social networks to more efficiently manage themselves is a much more promising business. Facebook will not disappear; it will transform. The network effects that have driven Facebook position it as the Comcast of the future. Social giants are building oceanic infrastructure.18 Logistics: the unsung hero of business melodrama. Digging ditches isn’t interesting; paired with radio-controlled helicopter delivered lattes, and you might have a chance. The most important strategy for an established social media company: run like a unicorn.

Just as politics in the United States are melodramatic, so is the economy: big stakes, loud theater, hypertrophied agency. This is an economy of winners and losers, dreams and ruins. Selling social media highlights the important, unique, special individual along with a model for a micro-transactional economy to a public buffeted by austerity and financialization. Just as the future was the central point of the economy in the past, the possibility of the self and potential are now bound up in the theory of the value of the attention of every individual. The story of social media—built around monetization, securitization, disruption, and litigation—is a magical story that makes sense of the entire economy. Selling social media is a disavowal of the processes of the past, the presentation of a suspiciously old new economy, and the promise that you are worth a fortune.