CHAPTER ONE

The Circle Is Sacred

The Ancient History of Medine Wheels

CIRCLES IN NATURE DRAW our attention. I see the concentric circles within the faces of flowers and their ovaries, fruits, and seeds. I study the geometric spiral in the face of a sunflower, like the patterns in inecones and acorns. The growth rings radiating from the heart-wood of a tree, which we count to learn its age, are classic circles of life. I am drawn to the circular rosettes of lichen colonies on tree bark and old stone walls. Patterning in nature seems to be a mosaic of circles.

The circle symbolizes many ideas for different people and provides healing, too. We are awed by the prehistoric circle of great standing stones at Stonehenge, in England, which relate to the perceived annual movements of the sun, and by the detailed circularity within pre-Christian labyrinths and Roman mosaics on temple floors. In our lives, the sacred protective link represented by a wedding band is a universal symbol. Hindus represent the great Wheel of Existence within a circle, and the Chinese, too, fashion the symbols of active and passive forces within the yin and yang of the universal circle. Tibetan lamas create a sacred universe within the circle of an intricate sand painting, as do Navajo sand painters pouring healing energies into their lengthy Chant Way ceremonies blessed with cornmeal.

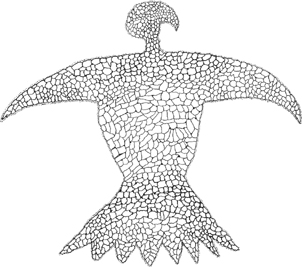

Labyrinths

Ancient Hopi medicine wheel—labyrinth petroglyph representing Mother Earth

Labyrinths are circular pathways within the great outer circle reflecting the spiritual journey of life. This ancient sacred geometry embraces a meandering but purposeful path to the center from the outer circle.

Walking a circuitous labyrinth path in meditation is a powerful tool for transformation, as it quiets the mind and opens the soul, evoking a feeling of wholeness and mindfulness. The path can be three, seven, or eleven circuits around the center within the great outer circle.

Unlike in a maze, there is no wrong way to walk a labyrinth. This mystical ritual, thousands of years old, is a metaphor for one’s journey to the center of understanding and to God. Labyrinths can inspire change, a sense of peace, and a deeper connection with the divine. The labyrinth is a sacred place, like the medicine wheel, and a universal symbol of peace.

Some labyrinths are planted with special herbs between the paths.

Traditional Papago spiderweblike design woven into sacred baskets

The Papagos’ Elder Brother, I’itoi, who gave the desert Southwest homelands to the people, the O’odham, is pictured within another ancient form of Native American labyrinth woven in their classic spiral basket tray. This traditional design is repeated on many objects in order to remind the people of the importance of their walk through life.

The sacred circle has long been a basic form in American Indian artwork, dwellings, clothing, and dances as well as in healing practices and rituals. Sacred drums, rattles, dream catchers, and bull roarers embody the circle and mirror the shape of the sun, moon, and earth. The year’s passage of time comes full circle and continues. Wherever we look, circles embrace us and teach us about the interconnections of all life.

ANCIENT STONE CIRCLES

Great stone circles are considered feats of ritual architecture. These are terrestrial and celestial markers on the landscape that have forever changed the land. Some authorities believe certain of these sites were solar calendars that regulated work and hunting among the people of these regions under the protection of the ancestors and gods. These ancient ruins have a certain spell about them that affects everyone who journeys to see them.

Striking parallels may be found between the prehistoric stonework of Europe, Africa, South America, and North America. Amazing similarities exist between the Celtic menhirs (tall standing stones), Mayan stelae, and the great standing stones of Easter Island in the Pacific, all marking sacred ritual sites. Also, stone cairns— Arizona stones carefully placed in a pile as a marker—are one of the earliest human constructions found around the world. Quite a few also have been found to have astronomical significance. The famous Big Horn Medicine Wheel in Wyoming, for example, is believed to act as a calendar device, much like Stonehenge in England.

Ancient medicine wheel overlooking the Long Canyon in the red rock country of Sedona, Arizona

Many ancient stone medicine wheels still dot our landscape from Canada to Mexico and from Florida to the Rocky Mountains. Across North America, they can be found from the Cree homelands on the plains of Alberta and Saskatchewan in southern Canada to the Ute territories in southern Colorado, Pueblo Indian sites in New Mexico, and east into the ancient Mound Builder sites along the Mississippi floodplains. They are usually located on prominent features of land, such as the summits of hills, plateaus, and ridges—places often hard to reach but well worth the effort of doing so. Earlier people must have journeyed great distances to reach these sites. Perhaps those journeys, much like pilgrimages, served to heighten the importance of such sacred places.

Scientists studying these enigmatic configurations in the late nineteenth century called them medicine wheels because of their similarities to the Plains Indian symbols commonly used in ceremonial artworks. For centuries, these Indians have made beautifully quilled circles with a simple cross in the middle. Plains Indian warriors often wore such a power symbol fastened to a war shield, their horses’ manes or bridles, or their own hair. Early settlers thought these resembled great wagon wheels. Whatever the location of the medicine wheel, at its heart is the circle, spiral, or cairn of stones. From this radiate lines of stones, and the ends of these lines become points on an outer stone circle. Sometimes the outer circle is closed, but it usually has one or more openings. The size, the form of the center, and the number of spokes vary in different medicine wheels, but the sacred circle is a constant theme.

Plains Indian medicine wheel ornament

Created over the course of the past 5,500 years, medicine wheels guard the mysteries of their ancient origins and uses, while tantalizing us to want to know them better as a vital part of this continent’s heritage. These stone circles continue to draw people to them for sacred, ceremonial, and healing necessities. Many seem to exude sheer power and energy, as I sensed so clearly during my visit to the medicine wheel site in Colorado.

The Sun Dance

The Sun Dance was born of visions and evolved out of ancient American Indian ceremonies. t flourished in the 1800s during the golden age of Plains Indian life. For some of the more than twenty Plains Indian tribes the Sun Dance was (and still is) the most important period of ritual and the only time of year when their people all gather at the same place. Elaborate ceremonies vary from tribe to tribe across the West, yet they all center on sacrifice and self-denial among the adult men and women. The Sun Dance may last four days and more, yet requires many days of preparation before it begins. Medicine Lodge and Spirit Lodge are also names given to the Sun Dance and certain of its aspects by some of the tribes.

Creating sacred space in which to pray, fast, seek visions, focus on group needs, or predict the seasonal behavior of game animals or the weather was natural for people living close to nature in much earlier times. They must have employed a variety of techniques to honor the land from which they drew sustenance. The prehistoric medicine wheel sites, mounds, and earthworks in North America suggest the heightened spiritual quality of particular places, “power spots” that seem to have served as primal cathedrals—shrines on the land. We need to reconnect with this.

There is clear evidence that Plains Indians camped at some of the medicine wheel sites over time. Remains of stone tipi rings and blackened earth from campfires exist at some sites. Elder tribespeople recall various stories and events celebrated around the medicine wheel. In some family traditions, people camped at the medicine wheel long before the introduction of the horse, when Plains Indians still used dogs to pull their travois. Some tribal historians claim that the medicine wheel symbolized the layout and design of the Great Medicine Lodge for the Sun Dance rituals. The Plains Indian scholar George Bird Grinnell wrote extensively about this connection, relating that the medicine wheel

is the place “where the instruction is given to the Medicine Lodge makers and from which the Cheyenne Medicine Lodge women carry the buffalo skull down to the Medicine Lodge.”

THE MOST FAMOUS MEDICINE WHEEL

Noted for its distinctive design and remoteness, the Big Horn Medicine Wheel is set high in the Big Horn Mountains near Sheridan, Wyoming. As you make your way up to this austere location, you can hear the constant call of the wind. Rugged junipers and prairie grasses hug the upper slopes, their foliage whispering in the strong wind. This famous site was sacred to the early Crow, Sioux, Arapahoe, Shoshone, and Cheyenne Indians who lived as nomads across the region. Some of their earliest ancestors probably constructed it. Distinctive features include the twenty-eight stone spokes radiating from the center and three cairns placed beyond the outer stone circle, all thought to have astronomical significance.

Big Horn Medicine Wheel in Wyoming

Studying medicine wheels for many years, especially the Big Horn site, astronomer John Eddy has concluded that they could have been used as horizon markers to identify the rising or setting of selected celestial bodies. He notes that the spoked pattern resembles a common sun symbol and comments that a Crow name for the Big Horn Medicine Wheel was “Sun’s Tipi.” Supporting this idea, Eddy also notes, one Crow legend reports that the sun built Big Horn “to show us how to build a tipi.”

The Big Horn Medicine Wheel is made of limestone slabs and boulders and is about ninety-eight feet across. The central cairn is about twelve feet in diameter and over two feet high. It was constructed on this high mountain plateau at an elevation of 10,500 feet in the early 1400s. This huge earth altar was used for many things, especially as a solar and stellar marking point.

The three outlying cairns at Big Horn align with three stars prominent in the summer sky: Aldebaran in the constellation Taurus, Rigel in Orion, and Sirius, the Dog Star, in Canis Major. These three stars appear as the biggest and brightest in the sky at the latitude of the Big Horn Mountains. Eddy explains that this site must have been an important mountain observatory in the twelfth to fourteenth centuries. The three stars rise almost twenty-eight days, or one moon, apart from one another, suggesting a connection with Big Horn’s twenty-eight long spokes. And in line with the idea that the medicine wheel inspired the design for the Great Medicine Lodge for the Sun Dance, there is persuasive evidence that Big Horn is a good marker for the summer solstice along the alignment of the central stone cairn with the distinctive outlying one. That is the time when many tribes came together to hold their Sun Dance ceremony with its days of ritual, fasting, feasting, and prayer.

Set in a windswept, rugged location some 425 miles from the Big Horn Medicine Wheel is the Moose Mountain Medicine Wheel, in southern Alberta, Canada. It bears such a striking resemblance to Big Horn that, according to scholars who study these sacred sites, it might have been built from the same set of plans. Constructed 1,700 years ago, it aligns with the same three

stars’ risings and the sun’s position as the Wyoming structure, to mark the summer solstice.

VISIONS, REMEMBRANCES, AND CEREMONIES

Crow Indian traditions tell that vision quests were held at or in the immediate vicinity of medicine wheels. Certainly these would be places of immense power for visioning. You have only to sit quietly at one of these sites and meditate for a time to feel the site’s strength and energy.

Research has revealed that some Plains Indians (especially the Northern Blackfeet; Dakota, Nakota, and Lakota Sioux; Mandan; Hidatsa; and Crow) also created monuments to memorable events by piling stones in cairns and by using simple outline effigy figures. These constructions are sometimes found within, but usually outside, the medicine wheels as ancillary features. A few tribal elders recalled that certain medicine wheels were constructed as death markers to honor a great chief. According to Blackfeet traditions, medicine wheels were created to mark the residence or grave of a warrior chief during historical memory. Their word for the medicine wheel is atsot-akeeh’: tuksin, which generally means “from all sides, a small marker of stones for remembrance.”

Canadian Inuit people constructed ancient rock markers they called inukshuk. Similar to cairns, these rocks were piled up to look like a person from a distance. They used these as guideposts and trail markers.

Some of the stone caims that have been examined contained offerings of both ceremonial and utilitarian objects. These suggest that the cairns were vital in the buffalo-hunting sequences in these regions. For example, two striking sites in Alberta, Canada, the Majorville Cairn and the Moose Mountain Medicine Wheel, both on windy hilltops, contained numerous prehistoric tools, many of which were used for scraping bison hides. Along with a

10 number of pipes, scientists also found iniskim, fossils used as bison-calling fetishes by the Blackfeet, as well as beads. Evidently, earlier people made valuable offerings in the cairns at the various medicine wheel sites. Such offerings might well have been part of a ceremonial event.

We don’t know whether ancient medicine wheels included plantings of healing herbs—in exposed, windswept places such as the Big Horn site, many would not do too well—but some tribal traditions point to a strong link between medicine wheels and healing. The ancient medicine wheel in the Red Rock country of Sedona, Arizona, rests on a high overlook above Long Canyon. These are the homelands of the Hohokam and Sinagua people of ten thousand years ago, distant ancestors of the Yavapai. They called this remote site Wipuk, meaning “at the foot of the rocks.” Their cosmology tells of how these people originated here at Wipuk, where the Creator taught them singing and dancing, which are forms of prayer. The creation story describes how the first human, Sakarakaamche, descended to earth on lightning flashes and sang a healing song as he knelt on the ground, causing medicine plants to grow wherever he touched the earth. The Yavapai say that as long as the songs are sung and the stories are told, the land will continue to live and flourish.

Certainly medicine plants merit a central place in a modern medicine wheel ceremony, adding their power to the other features of the design and the occasion. I have participated in such ceremonies, outdoors as part of a large group and indoors with a smaller number of friends and colleagues, especially when the weather is forbidding. We always begin with quiet smudging in the smoke of fragrant herbs such as cedar, sweetgrass, bearberry, and sage for cleansing. Usually everyone is asked to bring a grapefruit-size stone to place in the medicine wheel’s outer rim and smaller stones to add to the prayer cairns. Each of the larger stones can be designated to represent a celestial body: the sun, the moon, or a star or planet. A large stone each for Mother Earth and Father Sky hold the center. As people walk within and outside the medicine wheel circle, they contemplate their own life path and sense of destiny and commitments to their own

goals, asking for clarity and vision. Time for sharing afterward often brings additional clarity.

OTHER CEREMONIAL SITES

The medicine wheel has particular appeal for us today because it is a powerful spiritual structure that we can create for ourselves and fill with plants that give it additional potency. Yet many other kinds of sacred places abound throughout the Indian Americas.

Two millennia ago, along the rivers of what is now southern Ohio, a complex Native American culture arose, known today as Hopewell. The Hopewell culture flourished for over five hundred years, leaving behind mounds, earthworks, and dazzling artifacts as evidence of its existence. The Mound City Group in southern Ohio preserves the site of a major Hopewell ceremonial, and possibly social, center.

Another spectacle of the Hopewell site is the Great Serpent Mound. This impressive earthen structure represents a giant uncoiling snake; the oval embankment at the end may represent the snake’s open mouth as it strikes. This is the largest and best serpent effigy in the world: its sensuous shape curves and slithers across a quarter mile of lowland meadow on a ridge above Brush Creek. The Great Snake appears to be swallowing a large circle, perhaps an egg. Many North American The Great Serpent Mound mound sites are associated with burials and celebrations of the afterlife, but the Serpent Mound holds no human remains. The symbolism and ceremonial purpose of this inspiring structure remain a mystery.

We do know that the serpent, like the circle, has important meanings around the world. For Native American people, the serpent symbolized great power and energy, and among some tribes it signified one of the “keepers of the land.” The Hindus took the serpent as a symbol of enlightenment; for Christians it meant forbidden knowledge; the Greeks took it as a symbol of the life force

on the physician’s staff. For the Chinese and Japanese, the serpent force circulates energy, both in the body (where it is known through the ancient science of qt) and throughout the earth (where the practice of feng shui helps us draw upon it). The Toltec and Mayan peoples embellished their temples with serpents symbolizing wisdom and life force.

Today we instantly recognize the caduceus, two serpents intertwined around a staff, which has become the symbol of modern medicine. This comes from the ancient winged staff with two serpents that was carried by Hermes, Greek god of commerce. So much of our modern symbolism is based upon ancient inspirations.

Numerous other sacred sites are also worth exploring. Hundreds of effigy mounds (man-made earthen structures) in the shapes of birds, bears, men, cylinders, and flat-topped pyramids rise on the North American landscape. Effigy Mounds National Monument, in Iowa, preserves almost two hundred earthen structures ranging from simple mounds and cylinders to the forms of a bird, a bear, and various human shapes. Other effigy mounds can be found from Georgia and Florida to Wisconsin. Ancient petroglyphs and pictographs, such as the Great Spiral petroglyph in Saguaro National Park, Arizona, evoke a mysterious presence, a complex sense of the divine, expressed by ancestors who once peopled this continent.

Ancient spiral petroglyph in Saguaro National Park, Arizona

Perhaps the most unusual stone effigy mound site is Rock Eagle, near Eatonton, Georgia. This enormous bird effigy, with a 120-foot wingspan, is composed entirely of white quartz boulders. Created more than five thousand years ago by distant ancestors of the Cherokee and Creek Indians, Rock Eagle is older than the Great Pyramid of Egypt. Ancestral builders who created this site carried white quartz boulders and cobbles here from great distances. And like so many Native American sacred sites, this one is most impressive when viewed from the air. Many medicinal herbs surround this site, creating the impression that such places might have served as important healing centers.

The spectacular Chaco Canyon National Historic Park, in New Mexico, holds many tantalizing ruins of a sophisticated ancient culture whose sense of ritual continues to impress us. Numerous multiroom dwellings and carefully built kivas—large circular ceremonial chambers, partially underground—occupy the site. At many pueblos, great kivas like these still serve as healing centers wherein herbalists and ceremonialists come together for periodic festivals of renewal. This early desert city reflects the sedentary lifestyle of successful gardeners. Their advanced society included “sky watchers,” who observed celestial changes. The Anasazi, the Ancient Ones, the people of a Pueblo culture, pictured three particular symbols: a large star close to the crescent moon and a human hand nearby. Scientists conjecture that this painting represents their observation of a supernova widely observed around July 4, 1054.

Thousands of years before our European ancestors proclaimed their “discovery” of a new world, our Native American ancestors knew this ancient world was filled with countless spirits. They followed ritual practices to placate them. Clearly, the ancient sites were sacred space wherein the earth and the people were honored. We can only guess about ancient ceremonies and honoring rituals. And these sites still exude a source of power that many visitors feel upon visiting them.

From Chaco Canyon to the Great Serpent Mound and the Big Horn Medicine Wheel, many of the sites constructed by American Indian ancestors and sacred to their descendants are now managed and protected by the National Park Service; with great respect for Native American uses and sensitivities, they are open to the public. Others are on private property and not available to visitors. American Indians return to the medicine wheel sites for many reasons, often to seek a vision and endure a traditional vision quest. Each site remains a unique geographical feature of cultural, spiritual, and scientific significance.

For who but the people indigenous to the soil could produce its song, story, and folktale… who but the people who loved the dust beneath their feet could shape it and put it into undying ceramic form… who but those who loved the reeds that grew beside still waters and the damp roots of shrub and tree could save it from seasonal death and weave it into timeless art.

—Chief Luther Standing Bear, Lakota