THE POINTS OF FOCUS in a medicine wheel garden are the center and the four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west. Many Native Americans also add three more directions: zenith (above), nadir (below), and here. Welcoming ceremonies and sacred rites always honor the four or seven primary directions, as you will do in your own medicine wheel garden. These directions are the places of the spirits of the winds, the forces that govern life. A peace pole placed at the garden’s center marks zenith, nadir, and here. Similar cardinal poles can be anchored along the medicine wheel garden’s outer circle to mark the north, east, south, and west points.

Many cultures have imbued the four directions with larger meanings. East, the start of each day’s light and activities, is the place of sunrise, new beginnings, and birth. South is the place of warmth, nurturing, creativity, understanding, and youth. West is the place of sunset, arched rainbows, freedom, spaciousness, and maturity—natural connections for the direction where daylight ends. And north is the place of moonlight, stars, openness, wisdom, and elders.

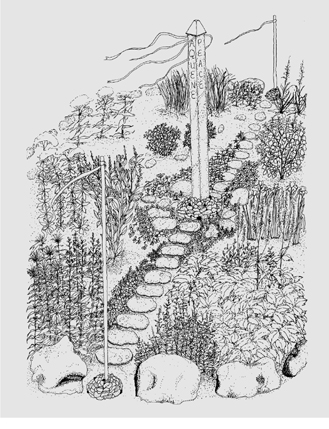

The medicine wheel garden plan, with special stones around the peace pole and prayer cairn

Before you deter-mine these important directions, you will need to lay out the enclosing circle of your medicine wheel garden. Whatever its size, start at one side of your site and pace to the other in a straight line, counting your footsteps. Turn around and follow your footsteps back, stopping when your count reaches the midpoint. If you have taken fifty steps, for example, stop at twenty-five. That is the center of your medicine wheel. Mark this spot by sinking a short temporary pole in the ground.

The stone center, outer circle, and directional cross of a medicine wheel garden give this sacred space its basic form. Some of the herbs you plant will be colorful and grow quite tall, but they should always be arranged so that the stone architecture remains clearly seen.

Tie one end of a long, strong cord around the pole. Holding the cord, pace from the center to the edge of your site (twenty-five steps in our example). Stretch the cord taut and tie a knot in it to establish your distance from the center. Now hold the cord at the knot, keeping it stretched taut, and begin walking in a circle around the center pole. As you walk, place a fist-sized stone or an-

chor a stake every few feet in your path. When you have completed your circle, take time to look over the site more than once and make sure that the size is just right for you. At this point, it’s easy enough to change your mind and make the circle larger or smaller, following the same procedure.

Depending on the size of your circle, you will need quite a few stones to mark the entire rim, a central circle, and the interior lines connecting the east-west and north-south points on the outer circle. When you begin planning for your medicine wheel garden, it’s a good idea to start a rock pile at the same time. According to where you live, your area might be rich in glacial stones, river cobbles, or other types of native rock. If too few stones turn up on your land, look for local sources that supply builders, or you can substitute brick or even wooden logs, if necessary. You may even find “cultured stone” available locally. (See Appendix 2 for resources.) Keep the temporary center pole in place until your medicine wheel architecture is complete.

Once your outer stone circle is in place, you can mark the cardinal directions. You already know in general the east-west direction from observing the daily path of the sun across your site. For a more accurate reading, dust off your magnetic compass. Stand at the center of your medicine wheel and find north on the compass. Holding the compass steady, so that the needle moves as little as possible, walk a straight northward line to your stone circle. Set a temporary pole at this point on the circle. Repeat the same procedure to find south on the circle, placing another temporary pole. Now tie the cord you used before to one of these two poles and carry it across the circle to the other one. When you stretch the cord taut, you know you’ve done things right if it passes across the center of the medicine wheel. Place marking stones along the path of the cord as a guide for making the giant interior cross, which will divide your medicine wheel garden into quadrants. Take the same steps for finding east and west on the outer circle.

Your medicine wheel pattern is now set. You can place more spokes in the wheel if you wish, by again following the procedure that you used to establish and connect the cardinal points.

The heart of the medicine wheel garden is the tall peace pole planted at the very center. Here you offer pinches of sacred cornmeal, tobacco, and your prayers. Your prayers might be for peace, healing, wellness, compassion, understanding, humility, and gratitude, or whatever seems most pertinent to you. Every person who comes into this garden and to the peace pole is invited to bring a small stone to place at its base with the thoughts: “I lay here my prayers for peace and understanding.” Soon this central area becomes a prayer cairn around the peace pole.

The simplicity of the circle with its interior spokes opens a world of possibilities for each gardener. While this book focuses on native American plants, you may easily substitute Eurasian, African, or Chinese plants to suit your own unique needs. Perhaps you want to create an Ayurvedic medicine wheel garden or a traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) wheel. I offer here several kinds of garden styles for you to choose from. Or you might want to use one or more of these styles as a springboard for designing a unique garden plan of your own.

Whichever garden style you choose or invent, you’ll want to be careful not to overcrowd plants. Allow them room to grow. Also consider the maximum height of each plant you want to include: take care not to start tall plants where they will overshadow

smaller ones, unless the smaller ones are shade-loving varieties. Consider the whole ecosystem of the garden, too. Perhaps you prefer to plant a large clump of one kind of plant to give a grounded, mature feeling to the garden space. It would certainly be interesting to see ten moccasin flowers blooming en masse, or ten jack-in-the-pulpits in a lively colony.

Native traditions connect particular colors to each cardinal direction. Most often, gold or yellow relates to east, blue or purple to south, red or magenta to west, and white or silver to north. But this can vary from one tribe to another. You may have your own vision or color sense for the cardinal (directional) poles.

The crossed lines connecting the cardinal points on the medicine wheel circle form directional quadrants, which define the spaces between north and east, east and south, and so on. You can fill each quadrant with clusters of healing plants whose color at some stage of development—blossoms, fruit, or foliage—coordinates with the colors symbolic of the related cardinal direction. According to your preference, appropriately colored plants can be

CLASSIC MEDICINE WHEEL

grouped around the dividing line representing the direction, such as east, or plant groups can be combined—for example, by placing those with colors appropriate to north and east in the northeast quadrant. You decide what will give you greatest pleasure.

One approach would be to choose five kinds of plants for each of the four quadrants, with low, ever-blooming strawberry plants placed around the central peace pole. Start with conservative selections chosen to suit the soil and climate of your site. Each season

you may add a few; the medicine wheel garden has much to teach and share as we cultivate it and grow with this project.

This garden features rugged coastal plants that can withstand sea winds, salty air, and sandy soil. The East and West Coasts both have appealing plant species. You might wish to cultivate low, creeping herbs in this garden, including rugged ground covers such as ajuga, alumroot, antennaria, bearberry blue-eyed grass, bird’s-foot violet, false heather, windflower, woolly thyme, vinca, heal-all, rabbitfoot clover, moneywort, hens and chicks, and se-dum—all add their own spirit to the garden design. Both native and introduced plants can intertwine here for textural diversity.

Spread broken clam, oyster, and mussel shells saved from seafood dinners and beachcombing expeditions among your plants. The shells will serve to sweeten your soil as lime slowly leaches out of them.

Perhaps you are lucky enough to have an oak tree or some bayberry and blueberry shrubs nearby. Look around for the wild onions, wild leeks, lamb’s quarters, nettles, dandelion, and chicory plants that may fill the hedgerows. These “garden escapes” from centuries earlier are now considered weeds, yet their healing benefits are considerable, and they fit in well with other selections for this medicine wheel garden. Many of these will simply jump borders and turn up in freshly disturbed soil.

COASTAL MEDICINE WHEEL

A xeriscape garden is a beautiful choice for people living where rainfall is scarce. The word xeriscape comes from the ancient Greek word meaning “dry.” Xeriscape gardening has its roots in our arid west and in Israel, where expanding populations depleted the already limited water supply forcing farmers and scientists to explore alternatives. It also draws on ancient gardening wisdom of the Hohokam and their descendants, the Tohono O’odham or Pima and Papago Indians. Making the most of drought-resistant plants, the xeriscape can become a showplace and teaching center. We all need to learn to use less water and natural resources while creating lovely gardens.

You can actually create a microclimate using the careful placement of rocks to help hold the soil in place, act as windbreaks, shade more delicate plants, and keep the underlying soil cool. Careful site inventory will help you determine your soil structure, terrain, and sun exposure and how to work to best advantage with these conditions. Choose the rugged native plants that thrive in your area, and group plants together within the medicine wheel to achieve low maintenance and water use.

Mulching in this garden is essential to retain moisture, maintain a reasonable soil temperature, control wind erosion, and inhibit the growth of weeds. Organic mulches break down over time and con-

tribute to soil quality and water-holding capacity. Select the mulch carefully to contribute to the appearance of the surrounding landscape and site design. You might wish to double-mulch, using select stone groupings over an organic mulch. See Chapter 6 for details.

Like the xeriscape garden, the desert Southwest garden grows on a dry landscape and uses the same system of frugal water and soil applications, relying heavily on rugged native plants. The enduring charm of this garden is that it embraces so many native plants that thrive in the desert Southwest.

Do your site evaluations carefully, with an eye to the rocks and other natural features you can use in this design. Any large boulders can become major focal points within or beside your medicine wheel garden. Perhaps you may want to bring in rocks from other places to create special effects.

As with the xeriscape garden, mulching is an important factor in nourishing these plants. Select mulches that harmonize with your environment and add interest as well as protect the fragile root systems of newly planted herbs. There are a number of distinctive stone mulches, for example, that might be layered over an organic mulch. Double-mulching in this case might be valuable. More details are offered in Chapter 6.

DESERT SOUTHWEST MEDICINE WHEEL

Plants that do best in the shade are a prime feature of the woodland garden. Often this type of garden is created near or surrounding a tree. Many of the unusual native medicinal plants thrive in rich, shady soil. Our first medicine wheel garden at the Institute for American Indian Studies in Washington, Connecticut, is bordered by a tall, old oak tree and partially surrounded with sumacs and witch hazel shrubs that help to cool the space through hot summer days. Do your site planning for this garden with an eye to how natural rock features can be used to hold the soil and protect it from erosion. You may also want to use tree rounds or logs as “sit-upons” in the garden and to help shade and cool some low-growing plants.

The prairie is known for hot sun, and a prairie garden features species that thrive on this. It might feature a combination of rugged grasses, yuccas, milkweeds, echinacea, and sages. Many native prairie plants could be situated here to portray prairie lands’ diversity of stunning wildflowers and grasses.

You want to first lay out the classic medicine wheel design on the land, as previously described. Perhaps you will create the great wagon wheel design with twenty-eight spokes, and choose eight different plants for each major quarter of the medicine wheel garden. Or just choose three or four plants for each quadrant of a smaller garden.

The medicinal/culinary garden combines vegetables with favorite culinary herbs. Make sure the deeply dug earth is well fertilized and balanced with sand, as most of these old favorite herbs are Mediterranean in origin and will thrive in sandy, neutral soil and full sun. Colorful carpets of nasturtiums might be planted to encircle the peace pole and cairn in the center.

American Indian children often worked in the family fields and gardens, where they had assigned tasks. Young children were

responsible for driving predatory birds and animals, such as crows, ravens, and chipmunks, out of the spring gardens where young plants were sprouting. The children would gather piles of small stones to throw at these garden thieves to oust them.

Growing children and growing gardens are natural complements. Children can closely experience the nurturing of seeds and roots into plants, and then into foods and health care aids. Gardening becomes an all-around learning experience. Training vines and pruning sucker growth from some plants is a responsible part of plant culture. As Halloween approaches, fun in the garden means watching the pumpkins and gourds grow to maturity.

Many of the healing herbs in the medicine wheel garden have glorious blossoms that attract bees, hummingbirds, and butterflies, along with a range of beneficial garden spiders. By midsummer, the garden becomes a colorful quilt of life with many insects to learn more about. Pollination, which is continually demonstrated in the summer garden, becomes a tangible theme for study. Building compost bins and carrying out the daily compostable remains from the kitchen adds another dimension to gardening and garbage disposal. Children like to watch the natural process of how, with their help, garbage recycles itself into usable garden humus.

The Mother Goose Garden is named after the old Mother Goose nursery rhyme popularized by Simon and Garfunkel in the hit song “Scarborough Fair.” The refrain “Parsley, sage, rosemary, and thyme” gives us the stalwart herbs for inclusion here. There are many hybrid varieties of each of these four classic Mediterranean herbs, so this garden will be colorful as well as highly fragrant.

Consider how children like to touch and sniff, and use this opportunity to enlighten, educate, and just have great fun in this summer garden. Because the carefully stroked foliage of each plant has a distinctive aroma and feel, this project can also be used as a fragrance garden for people with impaired vision.

The aromatic qualities of herbs have long served to stimulate the mind, ward off illness, season our foods, provide sweet perfume, and serve as valuable insecticides. The picked foliage of these plants, especially sage, rosemary, lavender, and onions, effectively chases stinging insects away when worn in a scarf or hat or tied in a bandanna around one’s neck. Children can make a pet’s collar, using a bandanna to hold several sprigs of herbs, twisted and loosely tied around the pet’s neck— the leaves are particularly effective there. Like all natural products, they need to be refreshed often, but what a pleasure!

Plants tell stories and stimulate new stories to be told. It is fun to investigate the origins of each plant and learn more about how it traveled the world, intersecting with the beliefs and economic and medical needs of different peoples.

With the classic medicine wheel design, you might place the parsley, sage, rosemary, and thyme each in a separate quadrant. You may want to place stepping-stones among the plants so that children can move easily within the garden without compacting the soil. Select several varieties of sage; perhaps pineapple sage, silver sage, golden sage, tricolor sage, and bronze sage plants might cluster around the most familiar one, the garden or kitchen sage, Salvia officinalis. Or you can plant multiples of just one species for attractive foliage and spring/summer blossoms.

Several delicious types of parsley and cilantro, and even celery and fennel, would create a fancy showing in the next quadrant of the garden. Parsley and other herbs with shiny dark green leaves

Train ornamental vines up the sides; plant shade-loving herbs inside

favor slightly more acid soil, whereas the gray-leaved herbs (sage, rosemary, and thyme) favor a sweeter, more alkaline soil. You may want to do some simple composting for these herbs by adding used coffee grounds and tea leaves to the acid-lovers’ soil, and crushed eggshells for the alkaline-lovers. Scratch these well into the soil and distribute them well around the plants.

For the last two quadrants of this garden, finish one with a selection of upright and weeping rosemary plants and the other with a grouping of various thyme plants. You can never have enough thyme! The thymes vary from soft gray to variegated (green and gold, or green and white) and deep green. All varieties have tiny oval leaves, and when stroked they release a heavenly fragrance.

If you choose to plant a wagon wheel garden with multiple spokes, you might add lavender, strawberry, heal-all, wintergreen, bearberry, and pennyroyal. Other childhood favorites are the tiny anten-narias, the dense, cosmopolitan pussy-toes, or cat’s paws. My mother remembers these small plants were called rabbit tobacco in rural Tennessee when she was a child growing up. Or you can choose your own regional favorites to plant within your design. Perhaps you will encourage the children to construct a twig tipi to stand in one quadrant of the garden to support a hops vine or passionflower vine for shade and added interest.

A good school project might be to establish a version of this garden as an outdoor classroom and adopt certain plants to study during the year, writing papers and doing research on each one as well as

caring for it in the garden. This is an excellent exercise in nurturing and creating sacred space. It might also be an interesting stretch to design and plant a Three Sisters Medicine Wheel Garden, focusing on regional varieties of corn squash, pumpkin, and beans, along with their “fourth sister,” the great varieties of chili, sweet, and hot peppers.

Fragrances are alluring pleasures. Many of the herbs we grow in our medicine wheel garden release their aromas in the summer heat when you brush by their foliage and blossoms. Capturing the volatile oils (the quickly escaping fragrances) in concentrated essential oils is an art that has been practiced for thousands of years. Many ancient cultures knew that fragrances can trigger emotional and healing responses in people. In fact, archaeological evidence reveals the use of essential oils in ancient burial sites.

René Maurice Gattefosse, a French chemist who investigated the chemical constituents in essential oils that aided the healing process, popularized the term aromatherapy in 1920. Many different essential oils provide amazing healing potential when smelled and rubbed on the skin. For this reason, and for pleasure, aromatherapy has become enormously popular.

American Indian sweat lodge rites include the fragrance of sage, pine, or juniper in the steaming mists rising off fire-heated rocks. Beyond sweat lodge rites, fragrance also played a role in diverse medicines and ceremonial rites. Many of the healing plants in the medicine wheel garden give particular aromas that perfume various healing applications. Bergamot (bee balm), American pennyroyal, bayberry, sage, sweetgrass, wintergreen, and yarrow are some of the most prominent. These herbs and their fragrances have antiseptic and antibiotic qualities.

Inhaling certain fragrances can bring back memories and stir emotions. Some fragrances, such as sage, sweetgrass, and yarrow, can be relaxing and grounding; other aromas, including the per-

fume of bee balm, sweet flag, and pennyroyal, can be invigorating and cleansing. Think of the intoxicating fragrances of ripe strawberries, vanilla, and chocolate.

A Fragrance Medicine Wheel Garden might feature selections from over two hundred herb-scented geraniums in the genus Pelargonium, which originated in South Africa. These highly perfumed ornamentals exhibit diverse foliage and blossom types. Their aromas mimic everything from nutmeg, strawberry, lemon, and lime to gooseberry, old rose, pine, ginger, orange, crème de menthe, chocolate, apricot, peach, and much more. Their leaves are used in teas, tisanes, creams, and lotions, and as insecticides. The geraniums are tender perennials in most zones, where they must be replanted from new stock each year. Many of us collect them, always adding to our favorite varieties when we find a new one.

One of my medicine wheel gardens is situated in full sun on a knoll, with deep loamy soil. My original goal was to have five different species of healing plants in each quadrant, for a total of twenty classic herbs in this large space. Preliminary plantings centered around the four sacred plants: tobacco in the east quadrant (yellow blossoms), sage in the south (lavender blossoms), bear-berry in the west (red berries following pink-white blooms), and sweetgrass in the north (white blooms). I placed large standing stones by each of the four special groupings, because these were my accent features and points of strength in the medicine wheel. I planted four of each species in a simple natural clump to encourage healthy growth.

I always want to start the medicine wheel garden with the four sacred plants—tobacco, sage, bearberry and sweetgrass— and give them particular care and attention. I offer special prayers and dig them in with extra cornmeal blessings and songs.

I based my next choices on what native medicinal plants would really do best in that garden site. I selected these additional

plants in groups of two and three for each species: epazote and shrubby cinquefoil in the east quadrant; blue flag and sweet flag in the south; butterfly weed, bee balm, and pineapple sage in the west; Cuban basil and jimsonweed in the north. I planted extra bearberry in the west-central sector around the peace pole and followed with strawberry for the north, creeping cinquefoil for the east, and heal-all for the south. I even found a stunning red-blossomed strawberry that is ever-blooming and ever-bearing, which I added in the west and north quadrants.

I made a special area in the north quadrant for a good-sized colony of my best broadleaf plantain, Plantago major. This old Eurasian healing herb is one of my reliable favorites. I use the sturdy green leaves as “innersoles” in my sandals and shoes because they relieve leg and foot fatigue and leave my feet feeling healthier. I even take small plastic bags of these leaves when I travel. A chewed leaf, or portion, will relieve stomach cramps and queasiness. In summer I roast the fresh seeds, grind them, and add them to vegetable dishes, as plantain seeds help soothe and regulate the digestive system. I also brought dandelion into the eastern quadrant, but I prevent it from going to seed. I used chicory in the south and purslane in the west quadrant because these, too, are valuable nutriceuticals (see more about this in Chapter 11).

In the much larger medicine wheel garden at the Institute of American Indian Studies, I followed the same plan. This garden is situated on a stone-ridden, shady western slope with slightly acid soil, suggesting different choices from those in my personal medicine wheel garden. Considering these conditions and the soil enrichments I had added, we planted the east quadrant with native species of arnica, St. John’s wort, and yellow dock. The south received sage, blue flag, and wild bergamot. For the west I selected bee balm, red-stemmed native angelica, and butterfly weed, and for the north quadrant mayapple, bloodroot, and sweetgrass. Again, we planted four of each species in a healthy little colony.

A big medicine wheel garden like this one, more than thirty feet across, can support a shrub in the middle of each quadrant, supplying extra shade for sun-shy native wildflowers planted be-

neath it. Remembering our colors, we included a witch hazel shrub in the east quadrant, an elderberry shrub in the south, a bayberry shrub in the north, and a sumac in the west. These shrubs provide wonderful perches as well as seeds and berries for songbirds and game birds. To keep them looking their best, each of these shrubs needs to be lightly clipped or pinched back several times during the growing season.