Figure 3.1

Predictions of partner choice and group selection.

3

Partner Choice and the Evolution of a Contractualist Morality

Two Views of Human Morality and Its Origins

Utilitarianism and Group Selection

Both in daily life and in empirical investigation, morality is often perceived as the opposite of selfishness. Being moral means helping others, often at a cost to oneself, and the more you help the more moral you are. In this way human morality is described as both generally “consequentialist” (i.e., we judge actions according to their effects) and specifically “utilitarian” (i.e., we most laud those actions that produce the most welfare, in this case referred to as “utility”).

Some moral judgments are consistent with utilitarianism. In the trolley dilemma, for instance, people are asked to decide whether it is acceptable to divert a trolley that is going to run over and kill five people onto a side track where only one person will be killed. In response to this dilemma most people agree that it is acceptable to divert the trolley, because it is better to save five lives than one. Similarly, participants in the dictator game, who decide how much experimentally provided money to keep and how much to transfer to another participant, generally transfer around 20 percent of the money. Again, this suggests that people consider the joint welfare of everyone impacted by a decision, although other motivations (e.g., selfishly maximizing one’s own welfare) can reduce how morally people behave.

How could natural selection produce behavior in contrast with selfishness? After all, individuals who sacrifice their own fitness to increase others’ fitness will, necessarily, have fewer offspring relative to others who just behave selfishly. Historically, one hypothesis has been that unselfish behavior is a result of group selection (for a critical overview, see West, El Mouden, & Gardner, 2010). According to group selection, groups with selfless individuals will outcompete other groups, such that the proportion of selfless individuals might increase in the overall population even while it decreases within the group.

However, there are many reasons to think that group selection is not an important factor in the evolution of morality (Abbot et al., 2011; Clutton-Brock, 2009; West et al., 2010) and that moral judgments are best characterized by moral theories other than utilitarianism. In the trolley dilemma, for instance, there are many variations for which people do not choose to save the greater number of people. People are not utilitarian in the “footbridge” variation, in which the only way to save five people is to push a bystander off of a bridge and in the way of the trolley (Greene, Sommerville, Nystrom, Darley, & Cohen, 2001). Furthermore, even the most characteristically utilitarian cases (e.g., the standard switch case) show deviations from utilitarianism: whereas utilitarianism requires that the maximum number of lives must be saved and allows that equal tradeoffs are acceptable, people do not think it is required to switch the trolley from five to one workmen, and they do not think it is acceptable to switch when there are equal numbers of workmen on each track (Sheskin & Baumard, unpublished data).

Importantly, antiutilitarian judgments are not limited to the artificial case of the trolley problem. For instance, people oppose organ selling even when they are told that allowing donors to sell their organs and receivers to bid for them would increase the number of lives saved (Tetlock, 2003). Similarly, people oppose a policy that would increase cure rates for one group of patients if it would also reduce cure rates for a second group, even if this second group is much smaller (Baron, 1995; Nord, Richardson, Street, Kuhse, & Singer, 1995). People also object to a distribution system that would sacrifice justice to efficiency (Mitchell, Tetlock, Newman, & Lerner, 2003). Moving from distributive justice to retributive justice, people refuse “overly” harsh punishments that would deter future crimes and thereby produce net benefits (Carlsmith, Darley, & Robinson, 2002; Sunstein, Schkade, & Kahneman, 2000). In the domain of charity most people refuse to risk their lives or to give large amount of money to save others, even if doing so would surely bring about more good than bad from a global perspective (Baron & Miller, 2000; Greene et al., 2001).

Given the many departures from utilitarianism, many psychologists have suggested that our moral cognition is beset with myriad errors or defects (Baron, 1994; Cushman, Young, & Greene, 2010; Sunstein, 2005). Baron (1994) suggests that nonaltruistic judgments could be the result of “docility” or “overgeneralization.” Sunstein (2005) has proposed that nonaltruistic rules are “simple heuristics that make us good.” They are generally good (e.g., “do no harm”), but sometimes they are mistaken (e.g., “do not kill anyone, even though it may save many people”). According to Cushman et al. (2010), such irrational judgments result from primitive emotional dispositions such as violence aversion, disgust, or empathy. In short this view of moral judgment has to address many departures from utilitarianism, and it often does so by suggestion that our moral psychology is plagued by diverse “moral confabulations” based on “alarm bell emotions.”

Contractualism and Partner Choice

In this chapter we advance an alternative view of both moral judgment and its evolutionary origins. Specifically, we propose an alternative solution to the existence of nonutilitarian judgments, in which they are not biases or defects but instead are the signature of a perfectly functional and adaptive system. In other words it has been assumed that the function of the moral system is to maximize welfare, and, with this premise in mind, it looks as if the moral system sometimes fails. But, if we assume a different function, these so called failures might be reconceptualized as perfectly functional. So what could that function be?

Consider the following situations:

• When we help financially, we do not give as much as possible. We give a quite specific and limited amount: many people think there is a duty to give some money to charity, but no one feels a duty to donate his or her entire wealth.

• When we share the fruits of a joint endeavor, we do not try to give as much as possible. We share in a quite specific and limited way: those who contribute more should receive more.

• When we punish, we do not take as much as possible from the wrongdoer. We take in a quite specific and limited way: a year in jail is too much for the theft of an apple and not nearly enough for a murder.

So it appears as though morality is not really about helping as much as possible. Sometimes, being moral means keeping everything for oneself; sometimes, it means giving everything away to others. Morality seems to be about proportioning our interests and others’ interests, for instance by proportioning duties and rights, torts and compensations, or contributions and distributions.

How can we conceptualize this logic of proportionality? Many philosophers such as John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and John Rawls have proposed a metaphorical contract: humans behave as if they had bargained with others in order to reach an agreement about the distribution of the costs and benefits of cooperation. These “contractualist” philosophers argue that morality is about sharing the benefits of cooperation in a fair way. The contract analogy is both insightful and puzzling. On the one hand it captures the pattern of many moral intuitions: why the distribution of benefits should be proportionate to each cooperator’s contribution, why the punishment should be proportionate to the crime, why the rights should be proportionate to the duties, and so on. On the other hand it provides a mere as-if explanation: it is as if people had passed a contract—but of course they hadn’t. So where does this seeming agreement come from? In order to answer this question, it is important to go back to the standard evolutionary theory of cooperation.

In the framework of individual selection, A has an interest in cooperating with B if it is the case that the benefits A provides for B will be reciprocated. This “if I scratch your back, you’ll scratch my back” is the idea behind reciprocal altruism and the standard reciprocity theory (Trivers, 1971). In this view if I give you one unit, then you give me one unit; if I give you three units, then you give me three units. But imagine that A and B are not equally strong. Imagine that A is much stronger than B and so feels secure reciprocating a benefit of three units with just one unit back. If we assume that B is stuck in her interaction with A, she has no choice but to accept any offer, as unfair or as disproportionate as it may be (André & Baumard, 2011; Schelling, 1960).

However, if we instead imagine that B is not stuck with A and has a choice among various collaborators, then she is likely to simply avoid A and instead enter into a mutualism with a fairer individual. This is what biologists call a biological market (Noë & Hammerstein, 1994). In this market individuals are in competition to attract the best partners. If they are too selfish, their partner will leave for a more generous collaborator. If, on the other hand, they are too generous, they will end up being exploited. If this “partner choice” model is right, we should see that the only evolutionary stable strategy leads to an impartial distribution of the benefits of cooperation (André & Baumard, 2012).

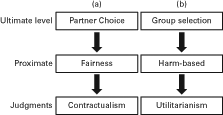

We summarize the two views of human morality and its origins in figure 3.1. In figure 3.1a, the partner choice model of evolution predicts a fairness-based moral psychology that produces judgments in line with contractualism. In figure 3.1b, the group selection model of evolution predicts a harm/welfare-based moral psychology that produces judgments in line with utilitarianism. It is not our intention to suggest that utilitarian theories of moral psychology are required to endorse group selection, but there is a natural progression from group selection to utilitarianism (i.e., “IF group selection were responsible for our moral psychology, THEN a utilitarian moral psychology would be the plausible result”). Likewise, our argument that moral judgments are contractualist does not require that partner choice is responsible for human moral psychology, but contractualism is a prediction of partner choice.

Figure 3.1

Predictions of partner choice and group selection.

Three Examples of Morality as Fairness

We are now in a better position to explain why people are “bad utilitarians.” In short, they are not utilitarians at all! Rather than trying to maximize group welfare, moral judgments are about allocating welfare in a fair way. Thus, distributive justice does not aim at maximizing overall welfare but at distributing resources in an impartial way (whether or not this is “efficient,” that is, producing the most overall welfare); retributive justice does not aim at deterring future crimes but at restoring fairness by diminishing the criminal’s welfare or compensating the victim (whether or not this deters crime); helping others does not aim at increasing the welfare of the group but at sharing the costs and benefits of mutual aid in a fair way (whether or not helping more would still increase the global welfare). In the sections that follow we discuss these three examples in greater detail.

Distributing Scarce Resources

When distributing scarce resources, such as income in the economy or life-saving resources in healthcare, utilitarianism defends the possibility of sacrificing the welfare of a minority for the greater benefit of a majority (for a review, see Baron, 1994). For a first example Baron and Jurney (1993) presented subjects with six proposed reforms, each involving some public coercion that would force people to behave in ways that maximized joint welfare. In one of the cases most participants thought that a 100 percent gas tax (to reduce global warming) would do more good than harm—with even 48 percent of those opposed to the tax conceding that it was a case of net good—and yet only 39 percent of subjects said they would vote for the tax. Participants justified their resistance by noting that the reforms would harm some individuals (despite helping many others), that a right would be violated, or that the reform would produce an unfair distribution of costs or benefits. As Baron and Jurney (1993) conclude: “Subjects thus admitted to making nonconsequentialist decisions, both through their own judgment of consequences and through the justifications they gave.”

In a second set of experiments participants were asked to put themselves in the position of a benevolent dictator of a small island with equal numbers of bean growers and wheat growers. The decision was whether to accept or decline the final offer of the island’s only trading partner, as a function of its effect on the incomes of the two groups. Most participants did not accept offers that reduced the income of one group in order to increase the income of the other, even if the reduction was a small fraction of the gain and even if the reduction increased the overall income (for similar results, see Konow, 2001).

Finally, in a third set of experiments a significant proportion of participants refused to reduce cure rates for one group of patients with AIDS in order to increase cure rates in another group, even when the change would increase the overall probability of cure. Likewise, they resisted a vaccine that reduced overall mortality in one group but increased deaths from side effects in another group, even when, again, this decision was best at the global level (Baron, 1995).

Although irrational in a utilitarian framework, this refusal to sacrifice the welfare of some for the benefit of others makes sense if our moral judgments are based on fairness to support mutualism. When being moral is about interacting with others in a mutually advantageous way, then, everything being equal, it is wrong to change a situation in a way that is of benefit only to some of the individuals. Individuals will only agree to situations that are, in fact, mutualisms (i.e., mutually beneficial). Forcing some individuals into a situation that is not to their benefit amounts to stealing from them for the benefit of others.

Punishment and the Need to Restore Justice

Intuitions regarding punishment do not follow utilitarianism and instead are based on restoring fairness. A utilitarian justification for punishing a wrongdoer might be that punishment deters future crime (by the previous offender and/or a new offender) by raising the costs of the crime above the benefits. Rehabilitation or isolation of a criminal can also serve as utilitarian justifications for punishment. However, people are mostly insensitive to each of these factors in their punishment judgments. For example, Carlsmith, Darley, and Robinson (2002) found that people’s punishment decisions were strongly influenced by factors related to retribution (e.g., severe punishments for serious offenses) but were not influenced by factors related to deterrence (e.g., severe punishments for offenses that are difficult to detect). These results are particularly striking in that Carlsmith and colleagues (2002) also found that people will endorse deterrence and are able to produce deterrence-based judgments if directed to do so.

More striking are cases in which people pursue retribution even when doing so reduces utility. Baron and Ritov (1993) asked participants to assess penalties and compensation for cases involving no clear negligence, in which there was a rare victim of a medication side effect. For example, one set of cases described a corporation that was being sued because a child died as a result of taking one of its flu vaccines. In one version of the story participants read that a fine would have a positive deterrent effect and make the company produce a safer vaccine. In a different version participants read that a fine would have a perverse effect such that the company would stop making this kind of vaccine altogether (which is a bad outcome, given that the vaccine does more good than harm and that no other firm is capable of making the vaccine). Participants indicated whether they thought a punitive fine was appropriate in either of the cases and whether the fine should differ between the two cases. A majority of participants said that the fine should not differ at all, which suggests that they do not care about the effect of the fine and only care about the magnitude of the harm that was caused. In another test of the same principle, participants assigned penalties to the company even when the penalty was secret, the company was insured, and the company was going out of business, so that (participants were told) the amount of the penalty would have no effect on anyone’s future behavior (Baron, 1993; Baron & Ritov, 1993). In all these studies most participants, including a group of judges, “did not seem to notice the incentive issue” (Baron, 1993, p. 124).

Although they clearly deviate from utility maximization, these judgments make sense in a mutualistic framework. If we consider that morality is about demonstrating and enforcing fairness, then a crime creates an unfair relationship between the criminal and the victim. If people care about fairness and have the possibility to intervene, they will thus act to restore the balance of interests either by harming the criminal or by compensating the victim. Data from legal anthropology are in line with this theory. Indeed, many writers have discussed the process of law in stateless societies with such expressions as “restoring the social balance” (Hoebel, 1954). In one of the first ethnographies on law and punishment, Manual of Nuer Law, Howell constantly emphasizes that the purpose of the payment is to “restore the equilibrium” between the groups of the killer and killed.

Thus, punishment seems to be motivated by restoring fairness rather than any other purpose (Baumard, 2011). Indeed, Rawls (1955) allows for the disconnect between the many utilitarian justifications for punishment and the retributive basis for people’s individual punishment decisions by suggesting that utilitarianism justifies only the institution of punishment (i.e., we have a legal system that punishes people because of the good societal effects of such a system), but that retributivism justifies each individual case of punishment (i.e., we punish an individual person based on the seriousness of his or her crime). By separating the moral foundations of the institution of punishment from the application of punishment in each individual case, this analysis may account for why we recognize and endorse the utility of punishment in general, whereas we base our judgments of individual cases on retribution.

Limited Requirement to Help Others

Perhaps one of the most counterintuitive aspects of utilitarianism is that there is no such thing as a supererogatory action—that is, an action “above and beyond the call of duty.” According to one straightforward application of utilitarianism, you are doing something immoral by spending time reading this chapter because it is not the action you could be taking right now to most increase worldwide utility. Instead, you should be doing something like donating (nearly) all of your money to charity and then committing the rest of your life to volunteer work. Contrary to the extreme requirements of utilitarianism, people do not typically think they have a duty to completely sacrifice their own interests to increase the welfare of strangers. This distinction between moral and supererogatory appears early on in moral development (Kahn, 1992) and is present in many moral traditions (Heyd, 1982). Instead of an unlimited duty to help, people perceive well-defined limits to other-directed behavior, and these limits are defined by the logic of fairness. Mutual help is not about being generous or sacrificing for the greatest good but rather about giving others the amount of help we owe them if we want to interact in a mutually advantageous way. For example, there are clear boundaries between failing to do one’s duty (i.e., only taking one’s fair share, not more), doing one’s duty (i.e., taking one’s fair share), and going beyond one’s duty (i.e., taking less than one’s fair share).

The contrast between utilitarianism and fairness can be seen in the classic Peter Singer (1972) article, “Famine, Affluence, and Morality.” Singer (1972) observes that we may feel an obligation to save a small child drowning in a shallow pond but no obligation to send money to save millions of lives in Bangladesh. He concludes that this departure from utilitarianism is irrational (see also Greene, 2008; Unger, 1996). This variability, however, makes sense in the theory of fairness. If we help others not for the purpose of increasing the global welfare, but instead because we want to interact with others in a mutually advantageous way, then our duty should take into account the relationship of those involved with a situation. In a systematic analysis of the Singer (1972) case, Unger (1996) argues that the main explanation of the difference for us between the drowning child and the dying Bangladeshis resides in the way we frame the situation. In the case of the famine we consider ourselves in a relationship with millions of Bangladeshis in need of help and millions of Western people who might potentially help; in the case of the drowning child, we are alone with the child.

Consistent with this analysis, experimental studies show that identifying a victim increases the amount of help: when a victim is allocated to us (as charities do in some cases), we feel that we have higher obligations to her: it is I and she and not we and they. Small and Loewenstein (2003) show that even a very weak form of identifiability—determining the victim without providing any personalizing information—increases caring both in the laboratory and in the field. In one striking example Small and Loewenstein (2003) found that people donated more to a housing fund when they were told the recipient had already been chosen, but not who it was, compared to when the recipient had not yet been chosen (see also Kogut & Ritov, 2005a, 2005b). Observations about rescue in war (Varese & Yaish, 2000) likewise show that people feel that they have a greater duty to help when an otherwise identical situation is seen as involving a small group (typically the helper and the person in need) than when it is framed as involving a large group (with many helpers and people who might need help).

This view of mutual help may also help explain why people feel they have more duty toward their friends than toward their colleagues, toward their colleagues than toward their fellow citizens, and so on (Haidt & Baron, 1996). People typically have fewer friends than colleagues and fewer colleagues than fellow citizens, and therefore, they should help their friends more because they constitute a smaller group. More generally, this mutualistic analysis, in contrast to utilitarianism, accounts for the fact that people consider that they have special duties toward their families or their friends and that they are not committed to increasing an abstract greater good (Alexander & Moore, 2012; Kymlicka, 1990). Indeed, the mutualistic theory can demand as much from us as utilitarianism, for example, if we are the only person able to help a family member.

Conclusion

For the sake of the presentation, we have organized the demonstration around three case studies of presumed “biases against utilitarianism”: distributive justice, punishment, and supererogation. However, we do not think there is a limited “catalog” (Sunstein, 2005) of biases against utilitarianism. All moral judgments have the same logic: respecting others’ interests either by transferring resources to others or by inflicting a cost on those who do not respect others’ interests. All moral judgments are the product of a sense of fairness.

Indeed, returning to the trolley dilemma with which we opened the chapter, a contractualist analysis can shed light on why it is acceptable to switch the trolley to a track with one person but not to push a person in front of the trolley. In the former case all parties are on trolley tracks, and it is only a matter of chance that the trolley is heading toward the larger group. Because the trolley might equally have gone down the other set of tracks, there is an important sense in which it is “not distributed yet” and all individuals have an equal right to be saved from it. On the contrary there is no natural way the trolley could have gone on the footbridge, and the trolley is clearly associated with the people on the tracks, and so saving the five amounts to stealing the life of the man on the footbridge. Notice that identical mutualistic logic is being applied in both cases. Thus, the switch and footbridge trolley dilemmas do not necessarily highlight separate features of our moral psychology (utilitarian and nonutilitarian) but instead can be accounted for by a single, nonutilitarian, fairness-based principle: when someone has something (e.g., safety from being in the potential path of a trolley), respect it; when people are on a par (e.g., they are all in the potential path of a trolley), then do not favor anyone in particular.

The link between the evolutionary level (the market of cooperative partners) and the proximate psychological level (the sense of fairness) is crucial. Without it, fairness and its logical consequences—the precedence of justice over welfare, the retributive logic of punishment, and the existence of supererogatory actions—look like irrational and unsystematic biases. In an evolutionary framework, by contrast, they are all a unified expression of fairness that serve as an adaptation for our uniquely cooperative social life.

References

Abbot, P., Abe, J., Alcock, J., Alizon, S., Alpedrinha, J. A., Andersson, M., et al. (2011). Inclusive fitness theory and eusociality. Nature, 471(7339), E1–E4.

Alexander, L., & Moore, M. (2012). Deontological ethics. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Available at <http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2012/entries/ethics-deontological/>.

André, J. B., & Baumard, N. (2011). The evolution of fairness in a biological market. Evolution; International Journal of Organic Evolution, 65(1), 1447–1456.

André, J. B., & Baumard, N. (2012). Social opportunities and the evolution of fairness. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 289, 128–135.

Baron, J. (1993). Heuristics and biases in equity judgments: A utilitarian approach. In B. A. Mellers & J. Baron (Eds.), Psychological perspectives on justice: Theory and applications (pp. 109–137). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Baron, J. (1994). Nonconsequentialist decisions. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 17, 1–42.

Baron, J. (1995). Blind justice: Fairness to groups and the do-no-harm principle. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 8(2), 71–83.

Baron, J., & Jurney, J. (1993). Norms against voting for coerced reform. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(3), 347.

Baron, J., & Miller, J. (2000). Limiting the scope of moral obligations to help: A cross-cultural investigation. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 31(6), 703.

Baron, J., & Ritov, I. (1993). Intuitions about penalties and compensation in the context of tort law. Making Decisions About Liability and Insurance, 7(1), 7–33.

Baumard, N. (2011). Punishment is not a group adaptation: Humans punish to restore fairness rather than to support group cooperation. Mind & Society, 10(1), 1–26.

Carlsmith, K., Darley, J., & Robinson, P. (2002). Why do we punish? Deterrence and just deserts as motives for punishment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(2), 284–299.

Clutton-Brock, T. (2009). Structure and function in mammalian societies. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. B, Biological Sciences, 364(1533), 3229–3242.

Cushman, F., Young, L., & Greene, J. (2010). Our multi-system moral psychology: Towards a consensus view. In J. Doris, G. Harman, S. Nichols, J. Prinz, W. Sinnott-Armstrong, & S. Stich (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Moral Psychology (pp. 47–71). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Greene, J., Sommerville, R., Nystrom, L., Darley, J., & Cohen, J. (2001). An fMRI investigation of emotional engagement in moral judgment. Science, 293(5537), 2105–2108.

Greene, J. (2008). The secret joke of Kant’s soul. In W. Sinnott-Armstrong (Ed.), Moral Psychology (Vol. 3, pp. 35–79) Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Haidt, J., & Baron, J. (1996). Social roles and the moral judgment of acts and omissions. European Journal of Social Psychology, 26(2), 201–218.

Heyd, D. (1982). Supererogation: Its status in ethical theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hoebel, A. E. (1954). The law of primitive man. Cambridge, MA: Atheneum.

Kahn, P. H., Jr. (1992). Children’s obligatory and discretionary moral judgments. Child Development, 63(2), 416–430.

Kogut, T., & Ritov, I. (2005a). The “identified victim” effect: An identified group, or just a single individual? Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 18(3), 157–167.

Kogut, T., & Ritov, I. (2005b). The singularity effect of identified victims in separate and joint evaluations. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97(2), 106–116.

Konow, J. (2001). Fair and square: The four sides of distributive justice. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 46(2), 137–164.

Kymlicka, W. (1990). Two theories of justice. Inquiry, 33(1), 99–119.

Mitchell, G., Tetlock, P. E., Newman, D. G., & Lerner, J. S. (2003). Experiments behind the veil: Structural influences on judgments of social justice. Political Psychology, 24(3), 519–547.

Noë, R., & Hammerstein, P. (1994). Biological markets: Supply and demand determine the effect of partner choice in cooperation, mutualism and mating. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 35(1), 1–11.

Nord, E., Richardson, J., Street, A., Kuhse, H., & Singer, P. (1995). Who cares about cost? Does economic analysis impose or reflect social values? Health Policy, 34(2), 79–94.

Rawls, J. (1955). Two concepts of rules. Philosophical Review, 64(1), 3–32.

Schelling, T. C. (1960). The strategy of conflict. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Singer, P. (1972). Famine, affluence, and morality. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 1(3), 229–243.

Small, D. A., & Loewenstein, G. (2003). Helping a victim or helping the victim: Altruism and identifiability. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 26(1), 5–16.

Sunstein, C. (2005). Moral heuristics. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 28, 531–573.

Sunstein, C., Schkade, D., & Kahneman, D. (2000). Do people want optimal deterrence? Journal of Legal Studies, 29(1), 237–253.

Tetlock, P. E. (2003). Thinking the unthinkable: Sacred values and taboo cognitions. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7, 320–324.

Trivers, R. L. (1971). The evolution of reciprocal altruism. Quarterly Review of Biology, 46(1), 35–57.

Unger, P. K. (1996). Living high and letting die: Our illusion of innocence. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Varese, F., & Yaish, M. (2000). The importance of being asked: The rescue of Jews in Nazi Europe. Rationality and Society, 12(3), 307–334.

West, S. A., El Mouden, C., & Gardner, A. (2010). Sixteen common misconceptions about the evolution of cooperation in humans. Evolution and Human Behavior, 32(4), 231–262.

Williams, B. A. O. (1981). Moral luck: Philosophical papers, 1973–1980. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press.