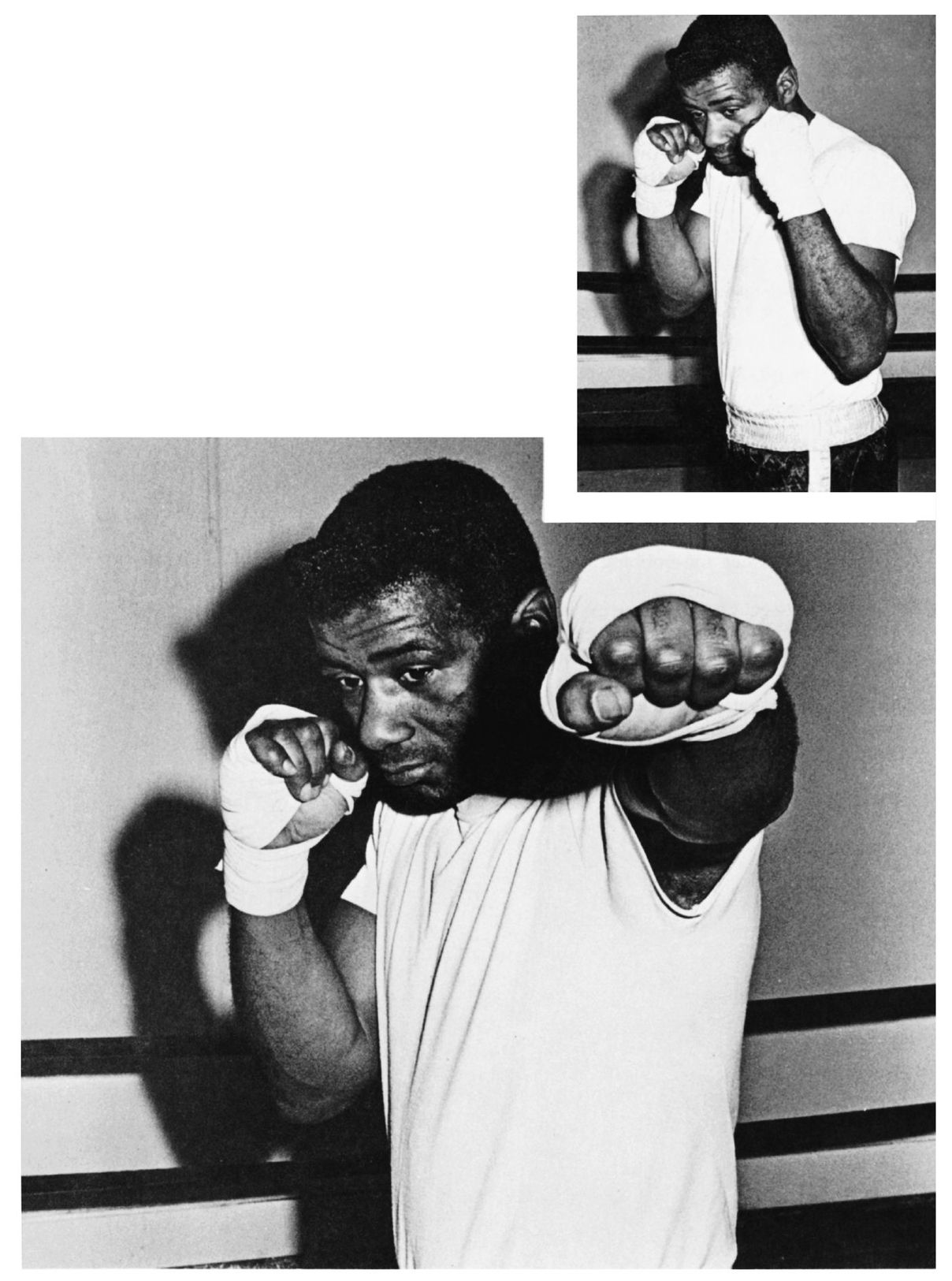

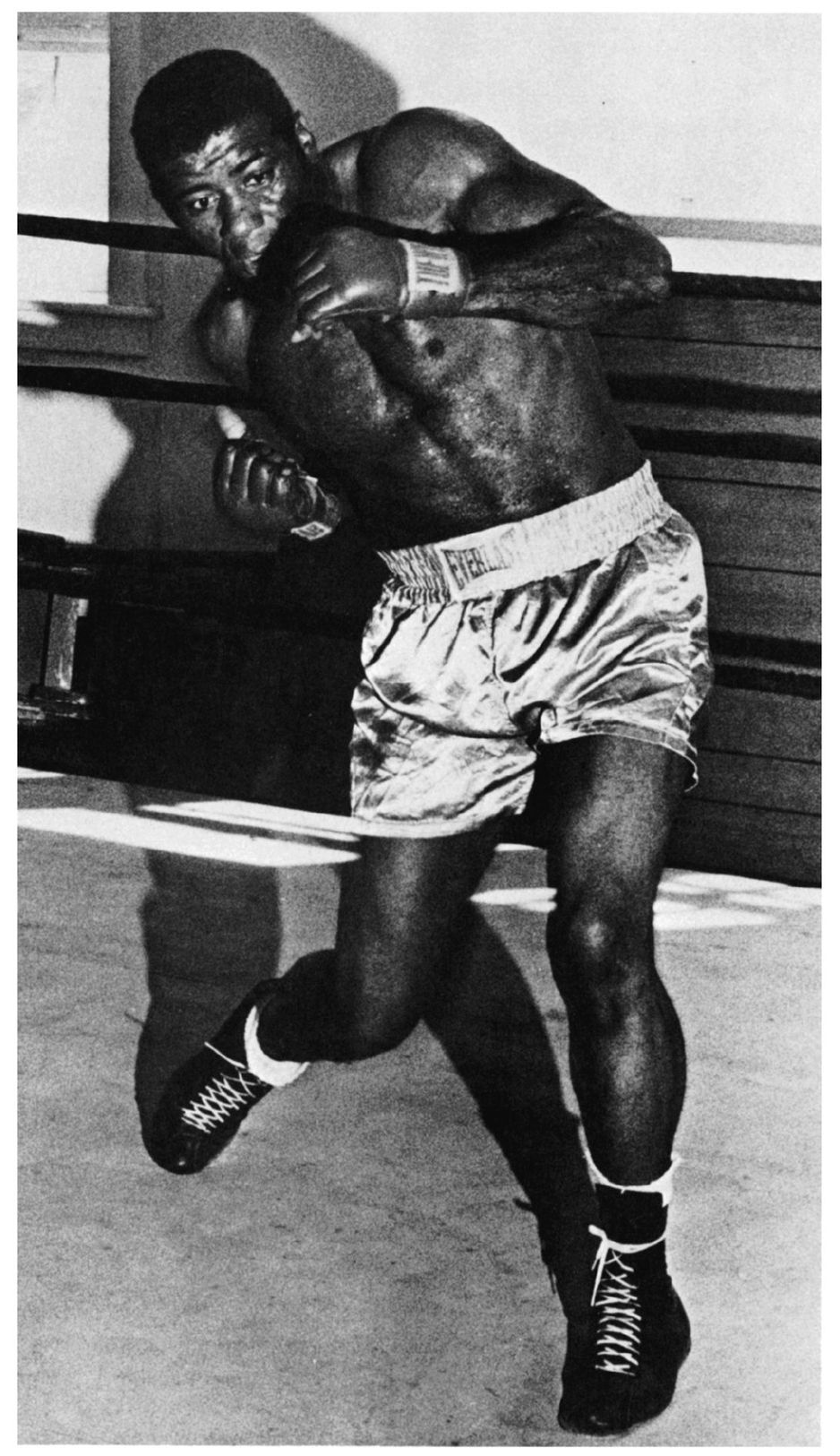

THE JAB . . . is the basic offensive weapon in boxing. The classic style of jabbing is straight from the shoulder.

3

OFFENSE

Every boxer has his own distinctive style of offense, but all boxers depend on a few basic punches—the jab, the right hook, the left hook, the uppercut, and the right cross. If you master these punches, you can use them to devise your own style and strategy of fighting.

THE JAB

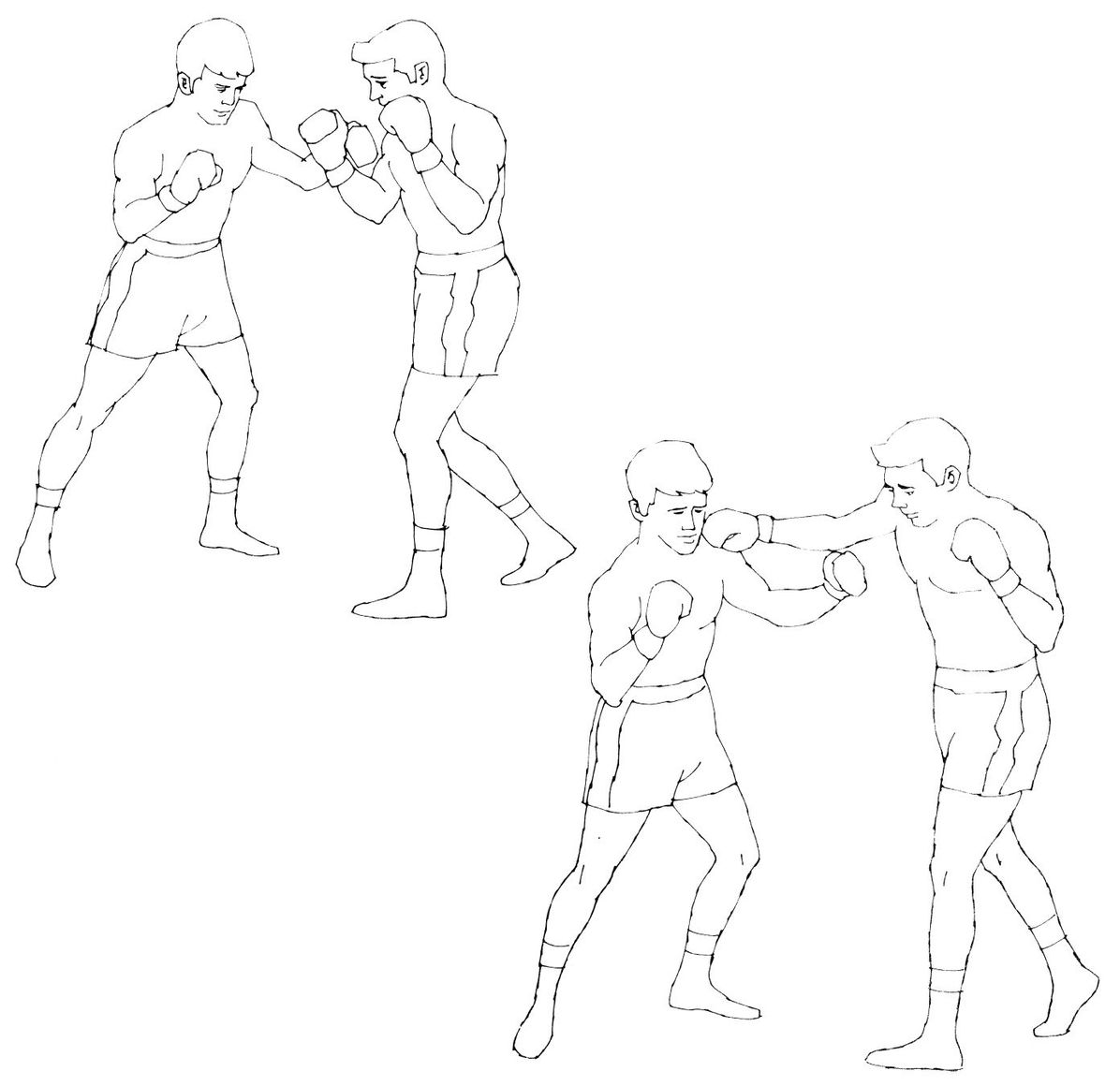

The jab is the first punch most beginners learn. It is your basic weapon in boxing (Diagram 5). The jab is far from the simple movement it appears to be. Its proper execution requires perfect timing and balance.

The jab is important not only because it is a fine offensive weapon, throwing your opponent off balance and creating openings for other punches, but also because it is a crucial defensive weapon. It can be used effectively in blocking your opponent’s right cross.

The jab proved to be a deadly weapon for Ingemar Johansson. It was Johansson’s left jab that set Eddie Machen up for the right-hand punch that knocked Machen out in the first round. And, in 1959, when Ingemar knocked me out to gain the heavyweight crown, it was his left jab that did it. In the actual fight, his left jab didn’t hurt at all. He caught me many times with it, but it was not proving to be an effective nor a devastating punch—or so I thought. After a while, I decided to stop wasting my energies in knocking down his left jab. Instead, I decided that I would just avoid the jab and think in terms of going on the offensive. It didn’t occur to me that his left jab was merely setting me up for his right hand. Johansson TKO′d me that night in three rounds. And I would credit the TKO not to the right-hand punch he landed but to his left jab, which had set me up for the punch.

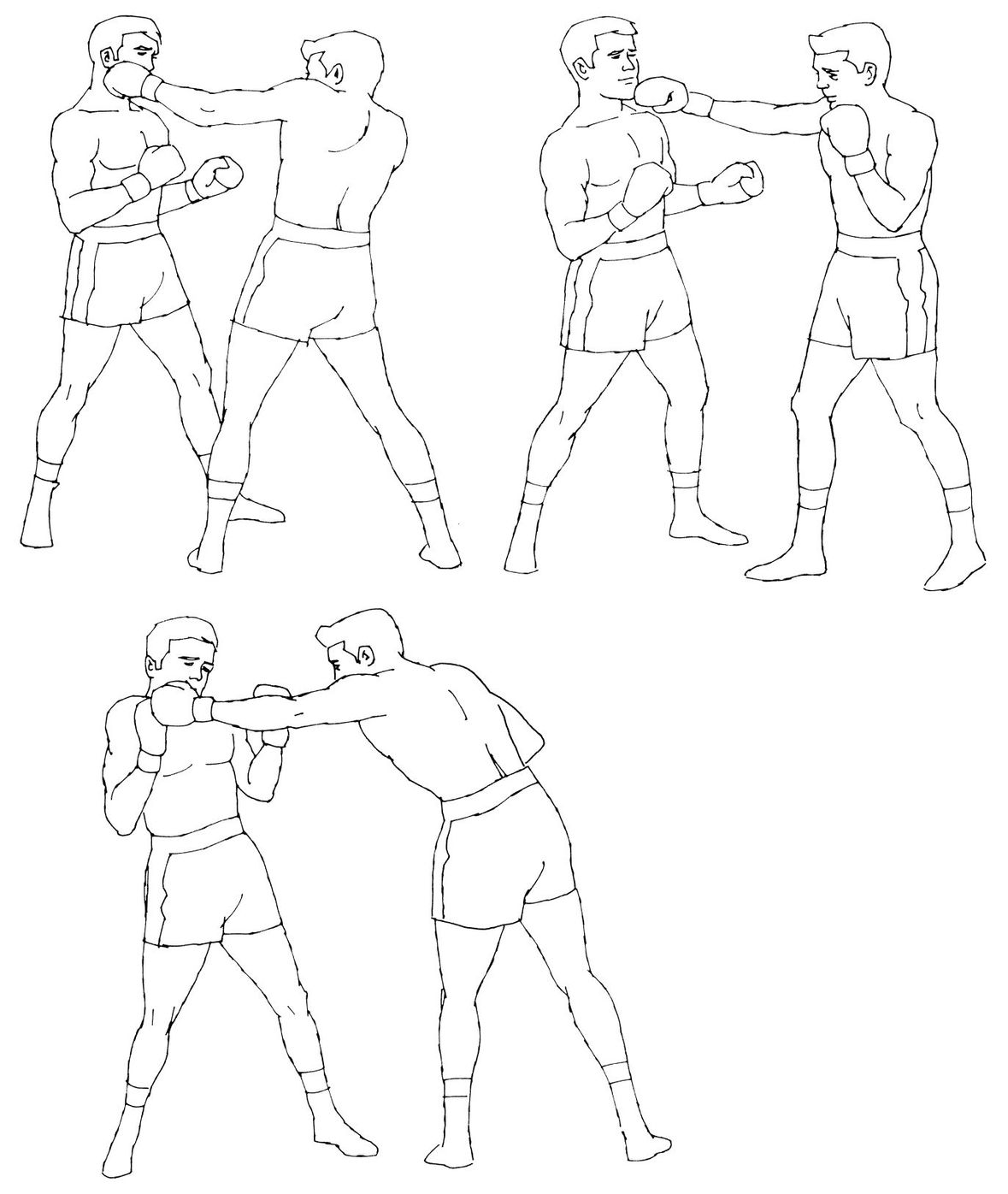

DIAGRAM 5. The jab.

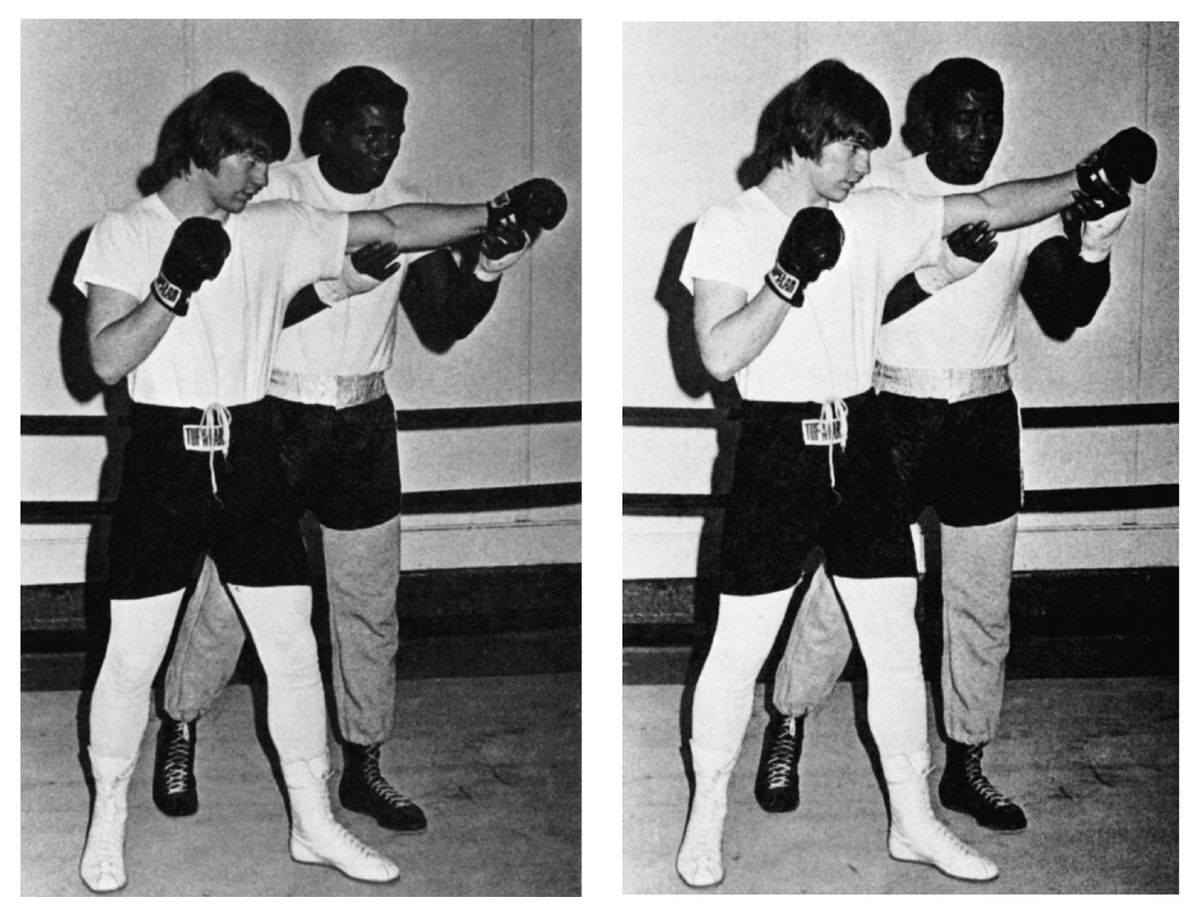

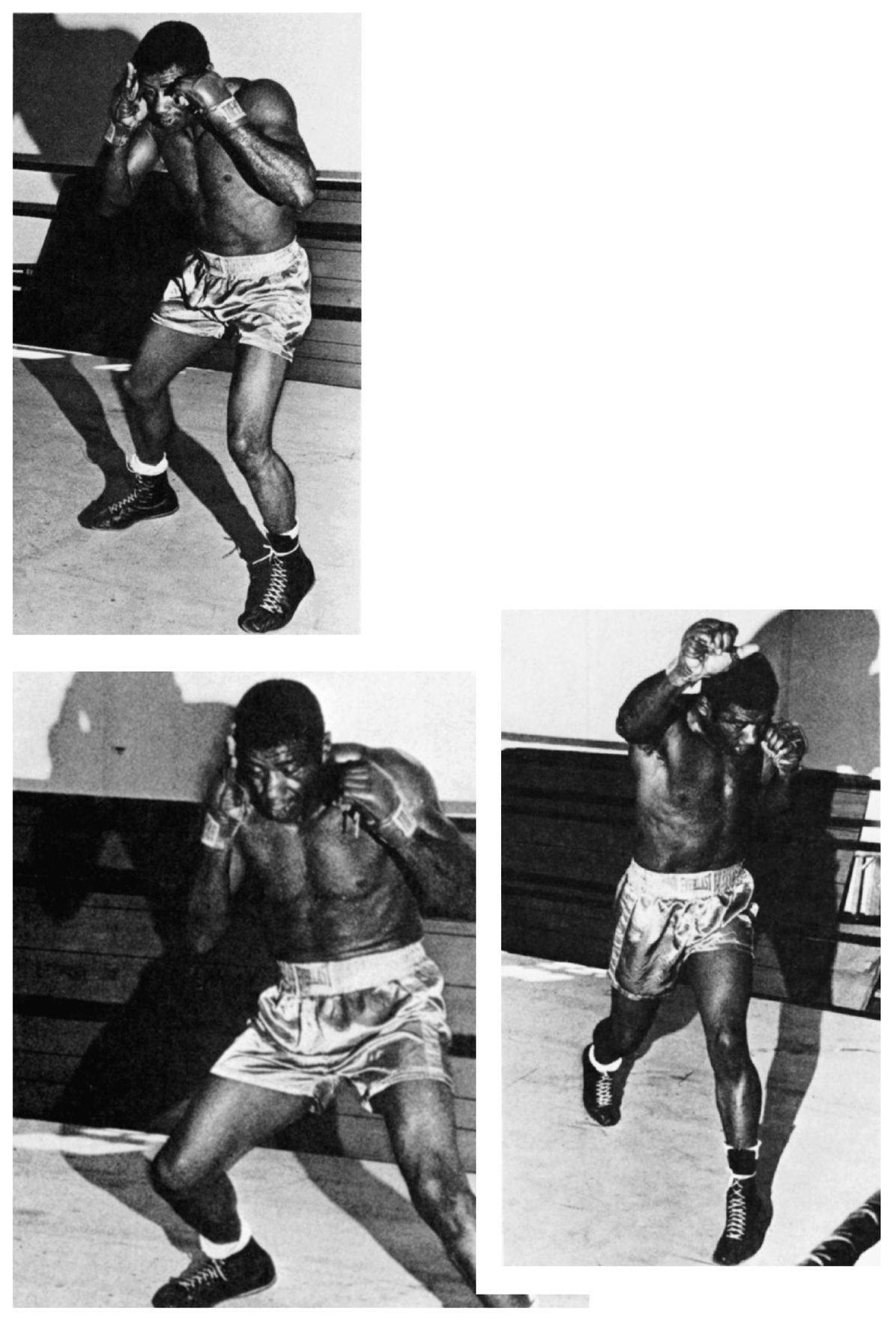

SHOULDER AND ARM POSITIONS . . . are crucial in getting force behind your jab. As I’m showing my student in these pictures, the arm should be kept straight but relaxed, and the fist should be turned at the moment of Impact.

In a later chapter, I will talk about the right jab, the offensive weapon for left-handed fighters. If you are right-handed, here’s how to throw the left jab properly. Make a quarter turn of your body to the right and extend your left arm. Start with the laces of your glove turned in toward you. Extend your arm, not too stiffly or tensely. Rotate your fist at the moment of impact, turning your hand over so that the laces now face down. Hit with the flat of your knuckles, so that you won’t risk injury to your wrist.

The classic style of jabbing is straight from the shoulder, using an extended, forward motion of the arm. Follow your straight left arm and step toward your opponent, moving your left foot. Step forward on your right foot and lift your right heel to maintain balance. Keep your thumb in, not only when you jab, but when you throw any punch. Keep your hands high so that your head and body are protected.

Move fast and bring the left hand back to the basic position quickly after you throw the jab. Practice continually so that you can jab and return in a flash. Each time you jab, bring your fist back just far enough to get leverage, then stick your arm out again. (You’ll hear some of the more advanced trainers yelling to their fighters: ″Stick it, stick it.″ By this, they mean “Jab.”) When you jab quickly and repeatedly, you are setting your opponent up for what is to follow, your right cross, your left hook, or whatever other punch you might throw.

The classic approach works well for most fighters, but every boxer should adopt a style that is natural for him. Many great fighters have thrown their jabs from other positions, often starting with their left hands down at the waist or even dangling at their sides. There is no one correct way of doing anything. However, in order to improvise and find your own style, you must begin with the basics and go from there. There are no shortcuts. By not knowing the basic movements, you will only penalize yourself and have little to fall back on.

A jab should be thrown at eye level, but if you are short and will be facing men taller than yourself, you will have to jab upward. By the same token, if you are taller, you will have to jab with a downward motion. If you are taller than your opponents, you will find the jab an especially fine weapon to have in your arsenal. While a jab is generally used only to the head, it can be effectively employed against the body if you are facing a taller opponent who holds his hands high.

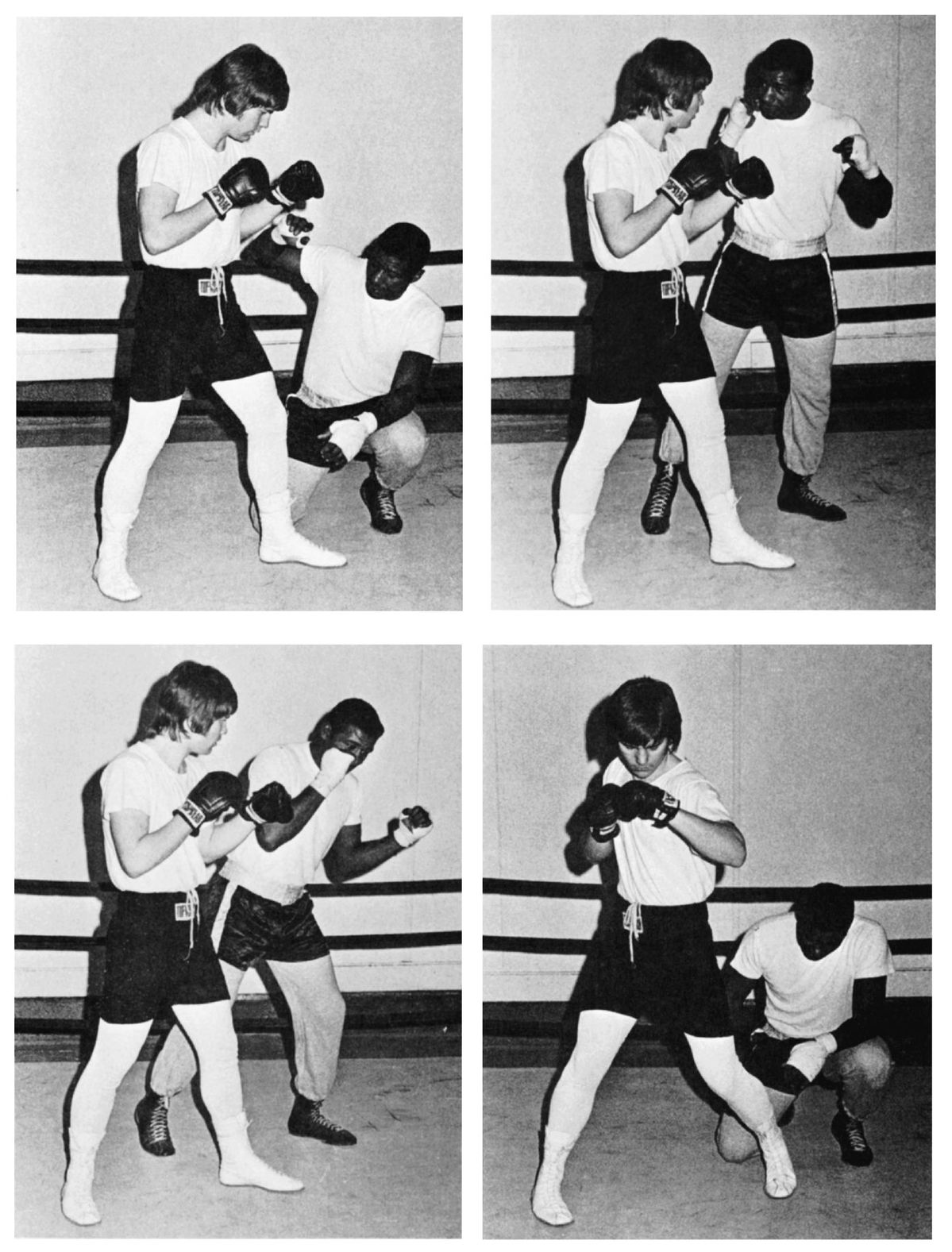

Practice makes perfect, and this is especially true of the jab. There are many ways that you can work to develop your jab. The heavy bag is the best method. Away from the gym, having a friend or your trainer hold up the palms of his hands for you to jab at will help sharpen up your jab. This method is excellent, as your partner can move around, moving his hands up, down, side-to-side, and in other directions, thus providing an unpredictable moving target.

USING YOUR PARTNER′S PALM AS A TARGET . . . is a good way to practice the Jab, especially if he moves his hand around to give you a shifting target.

THE RIGHT HOOK

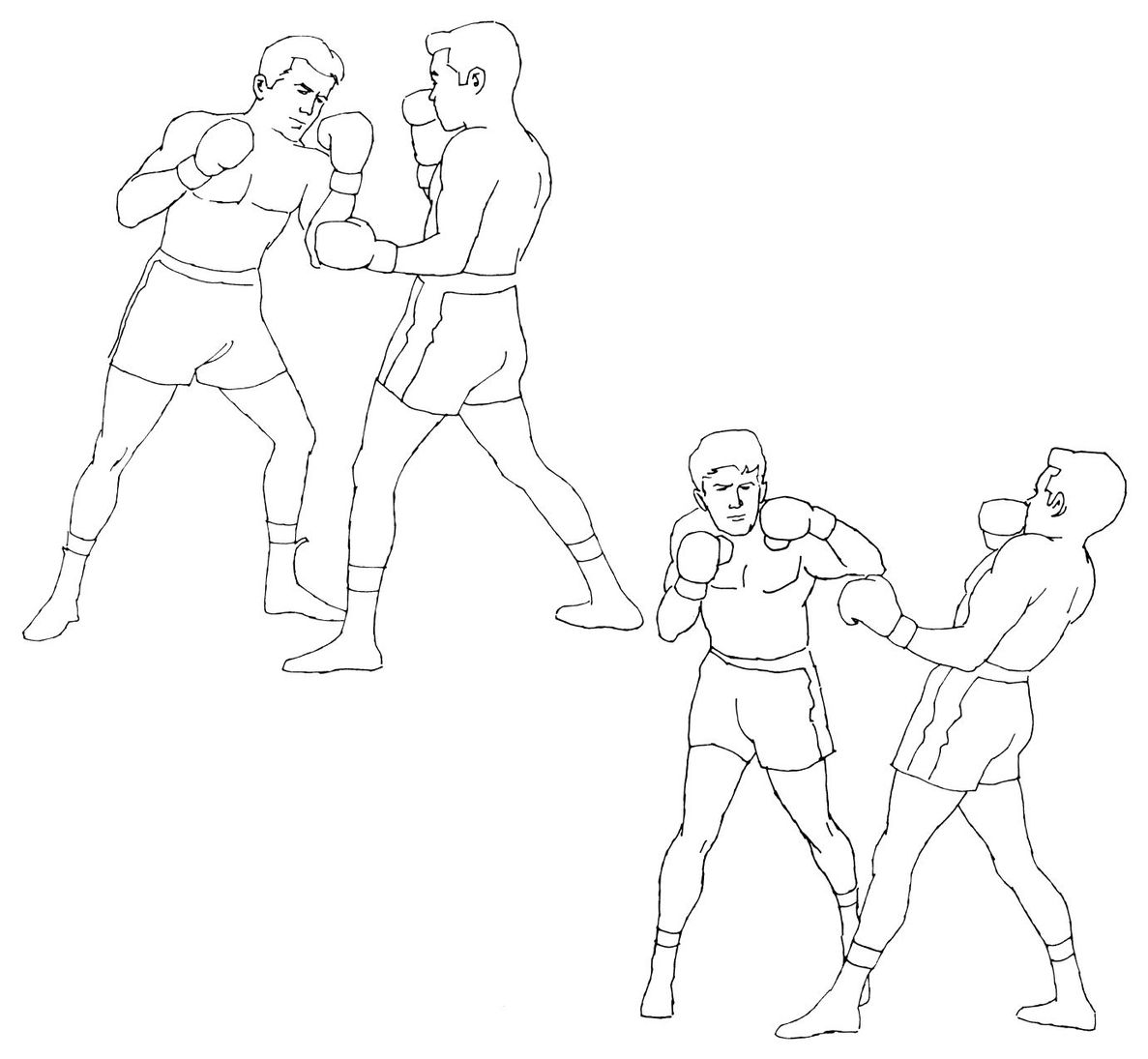

The right hook is a short, punishing blow that produces tremendous power because it has the entire weight of the boxer′s body behind it (Diagram 6). While purists insist that only a “southpaw” can deliver a right hook, a right-handed boxer can also throw this punch. Deliver this punch as you would a straight right jab, but bend your elbow away and raise your body up about 5 inches. As your fist hits your opponent, the laces of your gloves should be facing in instead of down.

Archie Moore and Sandy Saddler, two great former champions and two of George Foreman’s trainers, always advocated that the boxer turn his weight into the punch as he threw it. Maybe this is why they scored 140 and 103 knockouts during their careers, respectively. Throwing your weight before the punch reduces the effectiveness of the punch. Use your weight to follow through, in a manner similar to driving a baseball after you’ve hit it with the bat. The right hook, which is very effective when delivered in close to the body, should be delivered with the weight shifting from the right foot to the left foot.

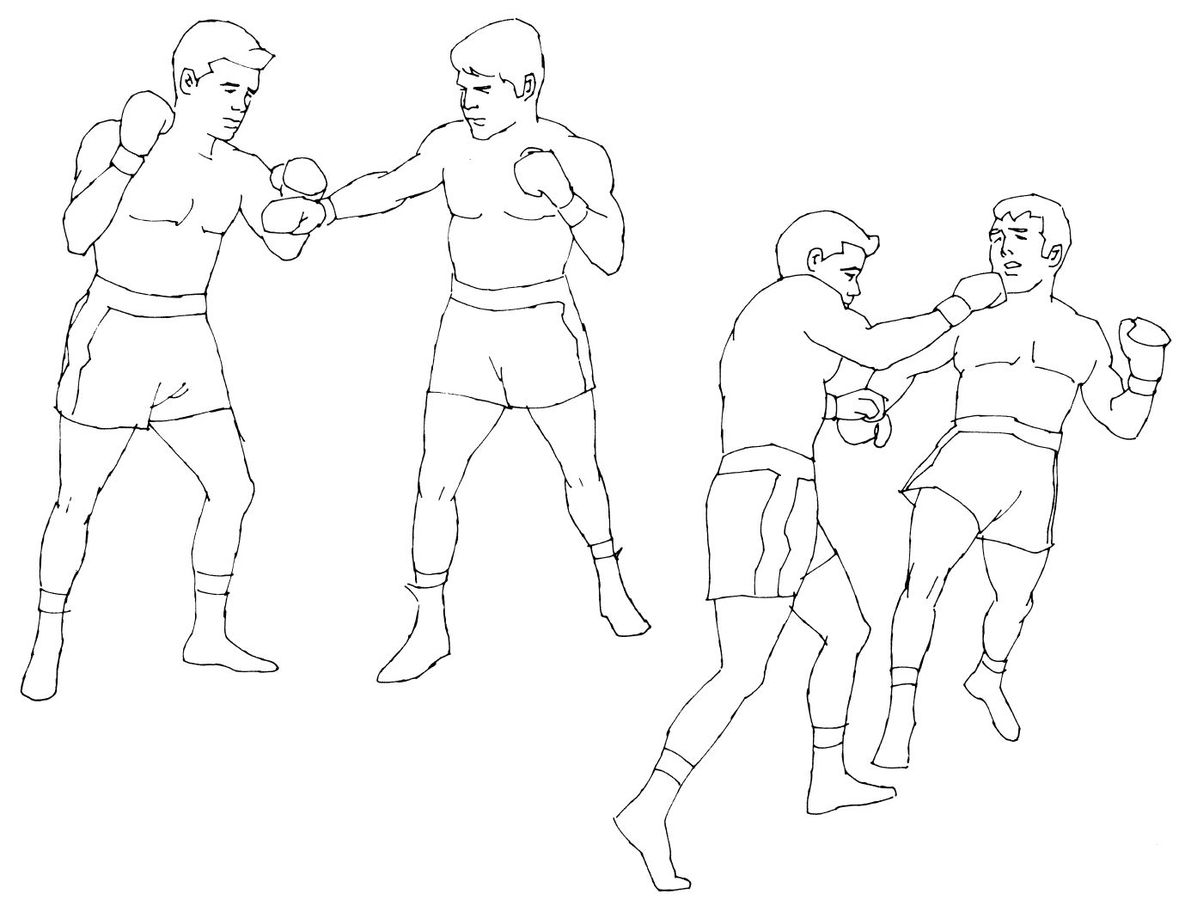

DIAGRAM 6. The right hook.

THE LEFT HOOK

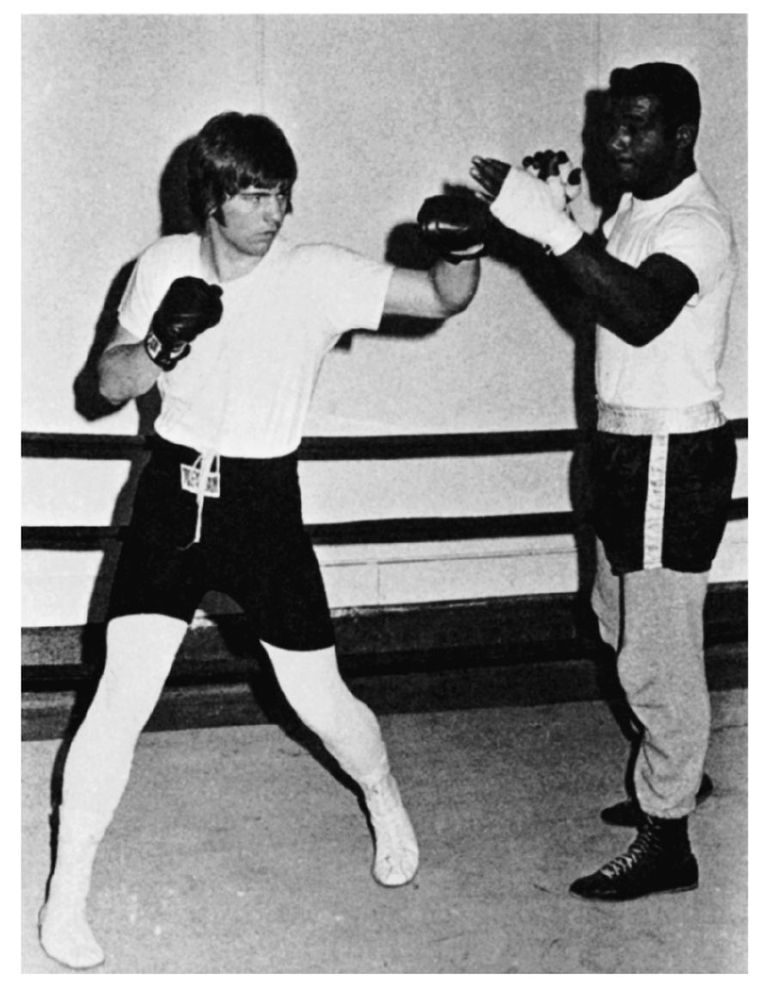

When delivered properly, the left hook is the most devastating punch in boxing (Diagram 7).

It takes a lot of practice to deliver this punch with power, but it is well worth it. Starting from the basic stance position, lean slightly forward and to the left, placing your weight on your left foot. Keeping your left elbow and arm in close to your body, turn your left hip and shoulder to the right. Keep your fist turned inward, laces inside and thumb up. Step forward, shifting your weight from your right foot to your left as you throw or whip the punch, raising your elbow about 4 inches. The left hook should be delivered in either an upward or level swing, depending on whether you are delivering the punch to the head or the body.

This punch can be delivered equally well from in close or at a distance. When you deliver it from a distance, however, remember to take a sliding forward step as you swing. I cannot overemphasize the need to shift your weight as you deliver the punch to gain maximum impact.

I myself like to deliver the left hook from a half crouch. When I leap forward I add the leg spring to the muscle power and weight behind the punch. I used this version of the left hook to bring back the heavyweight title when I knocked out Ingemar Johansson in five rounds in the Polo Grounds in 1960.

DIAGRAM 7. The left hook.

To practice the left hook, use the heavy bag and sparring with others. Shadow boxing and working out in front of a mirror will also help.

THE UPPERCUT

The uppercut is most effective for infighting because it doesn’t require much room to deliver. Throw the punch in an upward motion, with your laces facing you, so that the full force of your knuckles makes contact with your opponent’s chin (Diagram 8).

THE LEFT HOOK . . . depends on proper balance, speed, and coordination. Here I’m working with my student to correct his stance. Practice the movements of the left hook until they are spontaneous.

The uppercut is delivered in the same manner whether you use the left or the right hand. Bend your knees forward slightly, putting all of your weight behind the blow as you step in, swinging your arm upward. Your weight shifts to your left foot for a left uppercut and to your right foot for a right upper-cut. This helps the fighter maintain his balance and get the maximum amount of weight and power behind each punch.

DIAGRAM 8. The uppercut.

PUT ALL YOUR WEIGHT . . . behind the blow when delivering the uppercut.

Like any punch, the uppercut takes a lot of practice to perfect, and it is one that few fighters master. But it can be important to you in a fight that is fought in close quarters.

THE RIGHT CROSS

The left jab and the right cross form the classic one-two, the perfect combination in boxing. The jab opens the offensive and the right cross closes it.

Deliver the right cross from the classic stance. Hit right from the shoulder, with all of your weight behind the punch. As you release the punch, give your body a quick twist or turn at the waist, putting your weight on the ball of your right foot. Raise your elbow so that your arm is almost straight. As your arm crosses over from the right to the left side, your glove should be turned so that the laces are down (Diagram 9).

Your right leg should move forward as you step in with your left, and your weight should shift directly over to your straight left leg. In this manner, as you turn your hip and shoulder to the left, you will be able to deliver a sharp, stunning blow to your opponent’s head.

Maintain the proper balance and hold your left hand close to your body in a guarding position so that you are not left open to a counterpunch by your opponent.

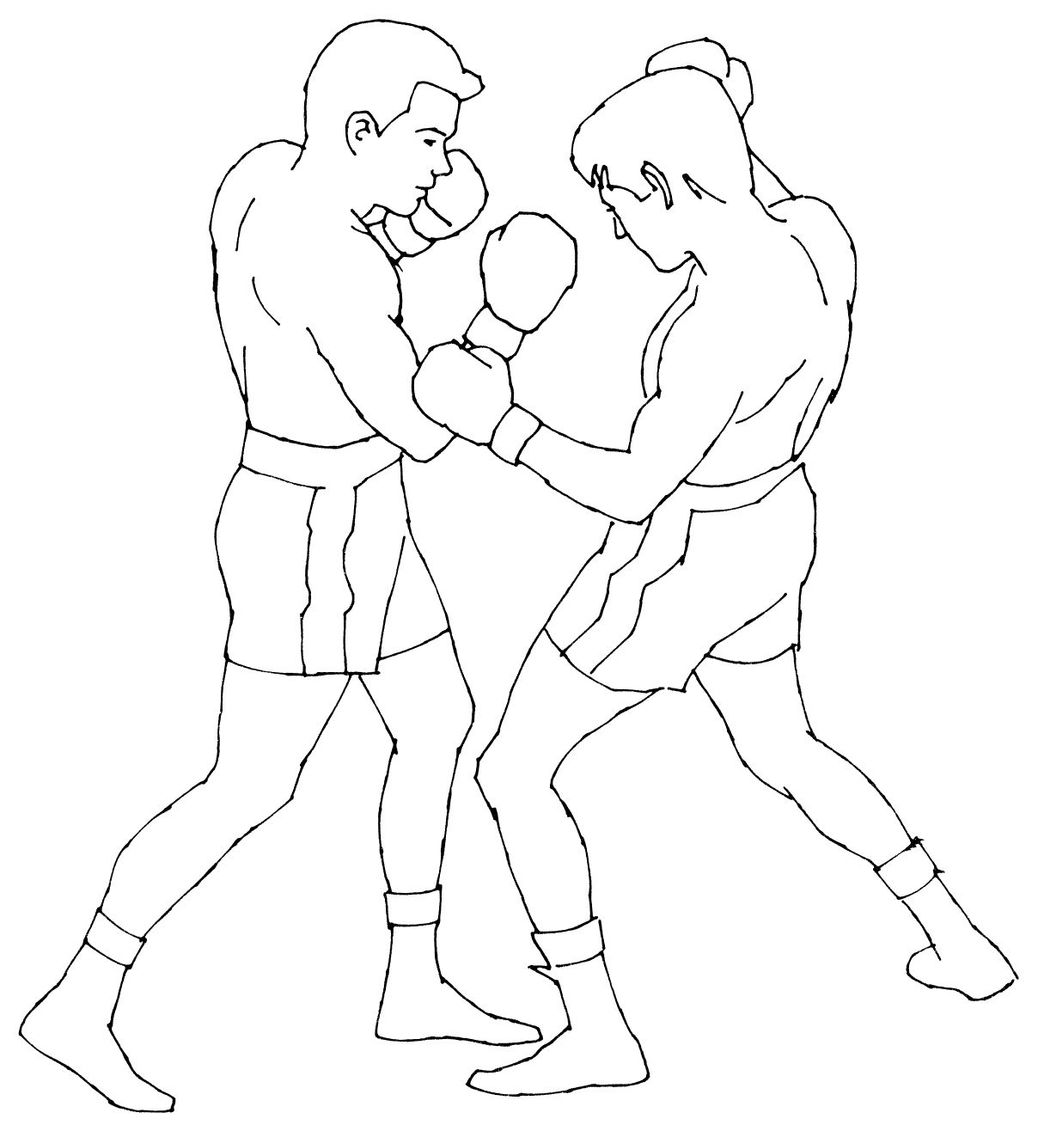

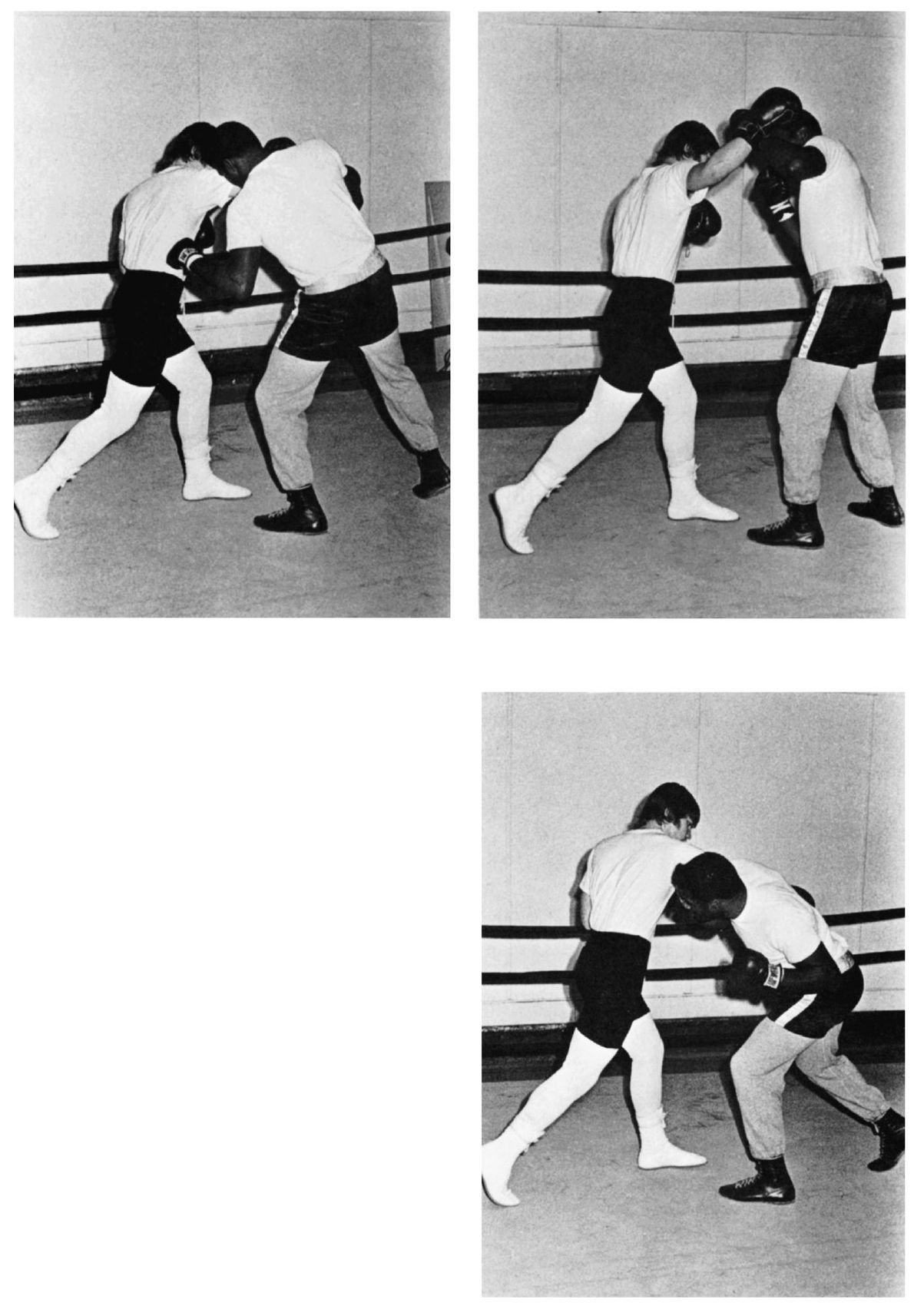

INFIGHTING

Infighting—fighting at close range—is an important aspect of boxing. In many ways it has become, like its main weapon, body punching, a lost art. Too many of today’s fighters are content merely to grab and hold when they get in close, clinching and waiting for the referee to break them apart rather than fighting in close. And, too often, they don’t even clinch correctly.

DIAGRAM 9. The right cross.

Infighting usually has been a short man’s game. Short arms are best suited for infighting and a short body makes for a smaller target, easier to defend. For some shorter men, like Rocky Marciano, infighting became a necessary tactic.

Position is the prime ingredient in infighting. The basic body, foot, arm and hand positions are the same for offense and defense in effective infighting. You need to maintain good balance, with your weight properly set, your knees slightly bent, your body bent at the waist, and your hand’s held in close, with your arms protecting your sides. This position lets you be on the offensive one moment and on the defensive the next.

INFIGHTING . . . is the art of fighting at close range. It is one of the best weapons of the average or short boxer. The secret of good infighting is to keep your opponent off balance.

Bobbing and weaving is an effective tactic for the infighter. You can duck in close to your opponent and come up punching. Short punches, hooks to the head and to the body, uppercuts and straight, short digs to the body are the tools of the good infighter.

Use your weight to press against your rival. The secret of good infighting is to keep your opponent off balance. Keep your hands inside your opponent’s arms, so that while you’re able to deliver your punches, your arms act as defensive blocks for the punches he throws at you. A good infighter learns to attack and to counter, taking every opportunity to turn the tide in his favor.

Although hitting and holding is an illegal practice, tying up both of your rival’s arms and hands while keeping one of yours free is not only perfectly legal, but smart boxing. This is not an easy maneuver, but one that can be a big plus for you. Draw your opponent’s arms together in front of him and wrap or pin your own arm around them from underneath. A competent referee will allow a man who has pinned his opponent’s arms and has one free hand to punch with his free hand. Bringing your head or shoulder up underneath the chin of your rival is also an illegal move, but using your shoulder to press an opponent off balance is not.

Training for infighting is a grind, but it is necessary. There are, of course, natural athletes in boxing as in other sports, but they are few, and most of us must depend on devotion and hard work to make the grade. I feel that lack of discipline is one of the reasons there are so few accomplished infighters today. If you want to succeed as a fighter you must be able to continue your fight on the inside. Infighting is much harder to learn and master than standing at long range and boxing. For those who master it, infighting can turn the tide in a close bout.

FEINTING

Like infighting and body punching, feinting has become a lost art. It is merely the art of out-thinking your rival and putting your ideas into practice.

José Torres, my former stablemate and the light heavyweight champion of the world, wrote a book called Sting Like a Bee. In his book, he gives the best definition of a feint I’ve ever heard: “A feint is an outright lie. You make believe you’re going to hit your opponent in one place, he covers the spot and your punch lands on the other side. A left hook off the jab is a classy lie. You’re converting an I into an L. Making openings is starting a conversation with a guy, so another guy (your other hand) can come and hit him with a baseball bat.”

FEINTING . . . can be used to draw punches from your opponent.

Remember, the hand is quicker than the eye. Being able to get your opponent to look for one thing, and then doing another is feinting. Feinting is using your head to draw an opponent into committing himself and then taking advantage of that commitment to counter him. Feinting is pretending to go to the body so your opponent drops his guard, and then going to his head, or vice versa. It is looking one place and punching another, or moving your feet as if to throw a left, when you’re really going to throw a right.

All of these methods of feinting can be perfected, but only through long, hard hours of practice. Again, a mirror is the place to start; then progress into sparring sessions. Don’t be disgusted with yourself if you fail at first—just keep practicing. The ability to out-think your opponent is essential to being a top-flight or championship-caliber boxer.

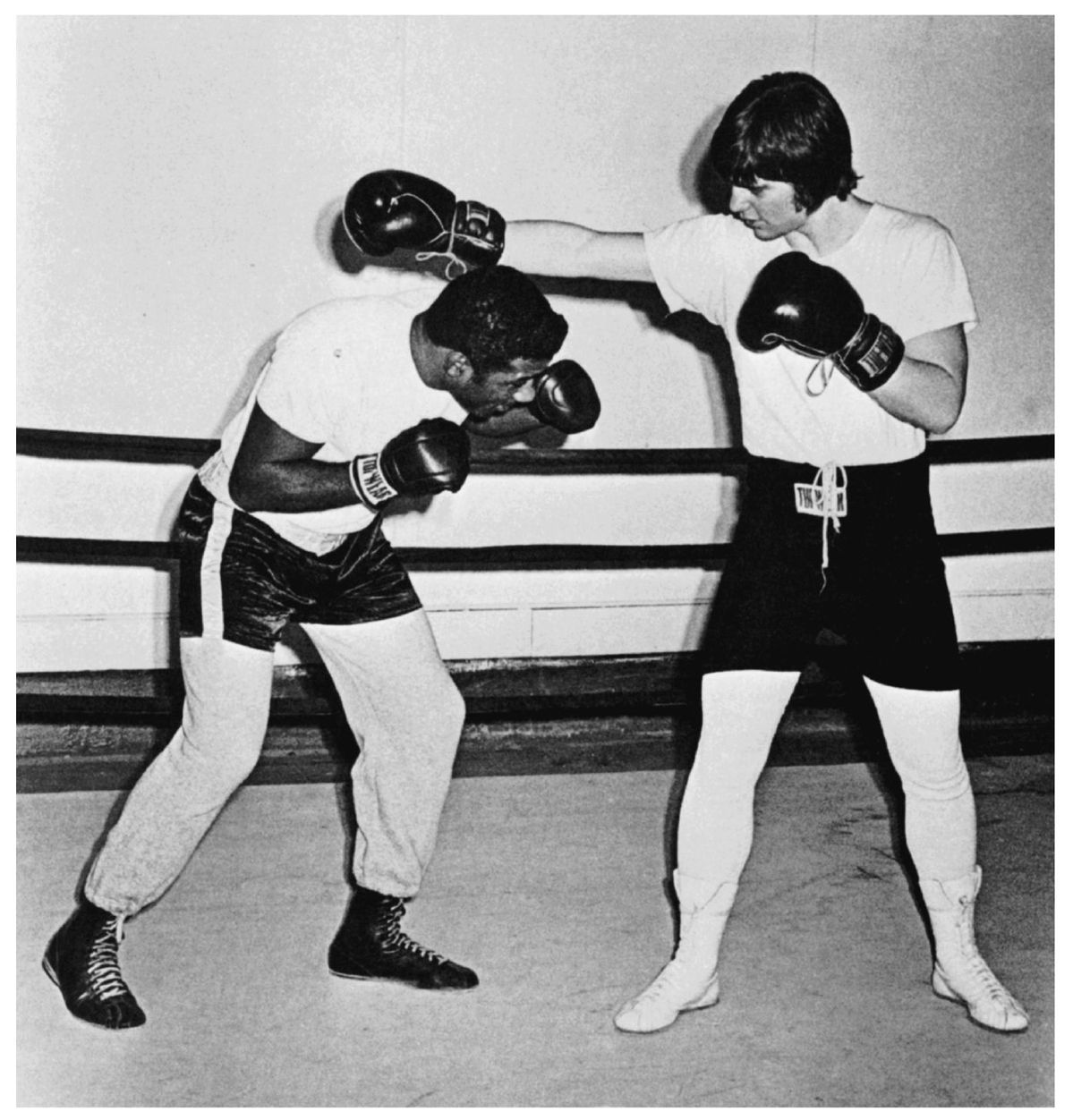

FIGHTING OUT OF A CROUCH

Like infighting, fighting out of a crouch works best for a short boxer. It makes him an even smaller target. But if you can’t develop a good style of infighting, don’t try fighting out of a crouch. A taller, long-armed opponent will just stay out of range and jab until you make a mistake—then BAM.

Bobbing and weaving is important to someone who fights out of a crouch, as is infighting. Another consideration is balance. If you don’t have proper balance, just a slight jab to the shoulder or to the top of your head could push you off balance, leaving you wide open.

FIGHTING OUT OF A CROUCH . . . is a good offensive weapon for someone who can move fast and has proper balance. From my well-known “Peek-a-boo” defense, I can explode with a straight right to my opponent’s head.

Archie Moore and James J. Jeffries were two big men who fought out of a crouch. I often fight out of a semi-crouch, to which my own “peek-a-boo” style is best suited.

When you fight out of a crouch, you must also be able to punch fast. Henry Armstrong and Joe Frazier are two boxers who throw their punches in bunches. Quick flurries are important to a crouch fighter, as he doesn’t have the style to set up his rival with probing jabs as does the straight, stand-up boxer.